Archangel, where the East comes abruptly face to face with the West

[Frontispiece: Sergeant William H. Bowman,

339th United States Infantry (missing from source book)]

THE AMERICAN WAR WITH RUSSIA

By

A Chronicler

(John Cudahy)

Nothing extenuate, nor set down aught in malice.—OTHELLO

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1924

Dedicated to the memory

of

SERGEANT WILLIAM H. BOWMAN

who died of wounds

received in the action of

1st March, 1919

near Toulgas, Russia

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Sergeant William H. Bowman, 339th United States Infantry (missing from book) ... Frontispiece

Archangel, where the East comes abruptly face to face with the West

Patrols with webfoot snowshoes went forth on the snow

Where a mill flaps its awkward wings

The blockhouses where men were crippled and maimed and shell-shocked so far away from gala Archangel

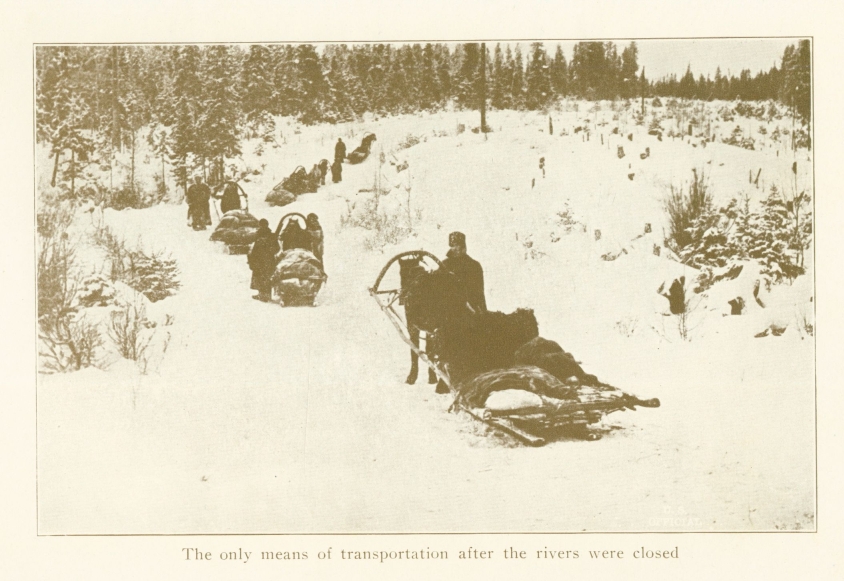

The only means of transportation after the rivers were closed

Patrols were often clad in white smocks

Major General Sir William E. Ironside

MAPS

The Murman and Vologda Railways

"This war was one of the most unjust ever waged. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies."

From Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant.

Commenting on the war with Mexico.

ARCHANGEL

THE AMERICAN WAR WITH RUSSIA

I

ARCHANGEL AND GALLIPOLI

"Theirs not to reason why;

Theirs but to do and die."

Many people have asked me about the Russian campaign, why American soldiers went to Siberia, and what they did after they got there, for the general notion seems to be that Russia and Siberia are synonymous, and that the Russian Expedition, whatever its hazy purpose was, was centered about Vladivostok, and that in this far eastern port, a few American and Allied soldiers "marked time," while their comrades on the Western Front fought out, and eventually conquered, in the greatest of all wars.

One American officer was actually ordered to join his command at Archangel, "via Vladivostok," and the order was issued by the War Department of the United States. Six thousand miles of inaccessible territory separated these two Russian ports, and the average American soldier who went out from Archangel in the fall of 1918, and, during the desolate winter months that followed, fought for his life along the Vologda railway, or far up the Dvina river, or in the snows of Pinega and Onega valleys, never knew that Brigadier General William S. Graves of the United States army, with thirteen hundred eighty-eight regulars and forty-three officers, had landed at Vladivostok on 4th September, 1918, and remained there after the Archangel fiasco had terminated. There was no conscious liaison between this American company of the far East and that of the far North, each performing burlesque antics in fantastic sideshows, while in the West, the greatest drama of all time was in its denouement, and a tense world trembled as it watched.

Whether there was any political connection between the Archangel Expedition and the Vladivostok Expedition is for the statesmen to answer. Surely there never was any military connection. Obviously, there never could be any support or communication between the two forces, and the American soldier at the Arctic Circle who was not told the reasons why he faced death and unknown dangers there, and why he was weakened and broken, and made old by privation and intense cold, never knew that there was a Siberian Expedition, and does not know even to this day.

So I have thought it worth while to tell, as faithfully as I could, the story of this strange war of North Russia, an insignificant flickering in the glare of the mighty world conflict, but inspiring in its human significance, its exploits of moral strength and sheer resolution and godlike courage. I have considered the campaign as a trial by ordeal of American manhood, that tested our souls to the depths, like Gallipoli tested the British. It was like Gallipoli in the hopeless odds encountered at every turn, in the vague outline of the commitment at the outset; in its distressing losses; its hardships and privations; its tragical ending.

But it was very vitally unlike Gallipoli, because in the war with Russia the soldier never knew why. The Australians, in their effort to force the Dardanelles, were exalted by the belief that theirs was an important operation in the war, and the British soldier went to battle the Turks, convinced that if he died, it was to save some little spot in a Cheshire or Sussex village, which to him meant England. It was a holy war, and men were fired with the high, selfless devotion of the Crusaders. An arrogant, brutal power swaggered abroad, menacing liberty, and the home and all things of the spirit. If German Imperialism engulfed civilization, there would be nothing left to live for anyway.

But there were no such reflections to sustain the soldier in Russia. The Armistice came, and he remembers the day as one of sanguinary battle, when his dwindling numbers suffered further grievous losses, and he was sniped at, stormed with shrapnel and shaken by high explosive shells. He heard of the cessation of blood-letting in France and Belgium, but for many desolate, despairing months, he stood to his guns, witnessing his comrades killed and mutilated, the wounded lying in crude, dirty huts, makeshifts of dressing stations, then in sledges, dragged many excruciating miles over the snow to the rear, where often they got little better attention than at the front lines. He knew his physical strength was failing under the unrelieved monotony of the Arctic exploration ration; he saw others with scabies and disgusting diseases of malnutrition, and wondered how long before he too would be in the same way. He felt his sanity reeling in the short-lived, murky, winter days, the ever encircling menace of impending disaster and annihilation. He asked his officers why he fought, and why he was facing an enemy vastly superior to him in strength and equipment and armament, and why he was separated from his family and home and the ways of life, and when the end would come. But his officers were silent under this inquisition. They asked the same questions themselves, and got no reply. The colonel who commanded this fated regiment told his soldiers that he could give no reason for them to oppose the enemy other than that their lives and those of the whole expedition depended upon successful resistance.

So soldierlike, he "carried on," while the dreary skies above him menaced death, and death stalked the encompassing forests of the scattered front lines, and the taint of death was in the air he breathed.

In the end, and when nearly all hope had fled, he returned homeward, stricken in health and dazed in spirit, where people moved as before, and were agitated by the same concerns, as if nothing had occurred to upset the whole scheme of things and uproot forever the old standards of values and ambition and morality. They noticed a queer look in his eyes and that he was customarily silent, often introspective. They manifested a casual interest in his great adventure. They never could understand.

Both expeditions were conceived by the British High Command and both were conducted by the execution of British military orders. Perhaps therein is the underlying philosophy of North Russia and Gallipoli; this attachment of the British mind to an astricted faith in England and her imperial destiny to rule the peoples of the world, contemptuous of obstacles and difficulties and perils in unknown, alien lands that appear very real to other than British mental processes.

"We'll just rush up there and re-establish the great Russian army—reorganize the vast forces of the Tsar," said an ebullient officer in England, wearing the red tabs and hatband of the General Staff. "One good Allied soldier can outfight twenty Bolsheviks," was the usual boast of the Commanding Officer in the early days of the fighting.

And it was a boast that was made good in the furious winter combats, when, standing at bay, the scattered companies, with no place to retreat, save the open snow, stood off many times their number of the enemy. In these decisive trials, the spirit of the Anglo-Saxon ever asserted its superiority, but one to twenty is not a very comfortable ratio upon which to form an offensive campaign. And the war against Russia was conceived as an offensive campaign, whatever it turned out to be.

"The Emperor fully realized the nature of the task he had before him. To defend himself in Italy, Germany or even Poland against the Tsar was one thing; to invade the vast empire of Russia, was another task altogether—a task colossal, if not appalling. And arrayed against him were two fearful enemies—the Russian Army and winter."

WATSON'S Napoleon.

II

RUSSIA THE VAST UNKNOWN

Sometimes we are amused by foreign littérateurs and commentators, who come to our great country for a few crowded weeks of teas and symposia, gatherings of the intelligencia in our metropolis, and perhaps a dash into the mushroom dilettantism of Chicago, to set sail and compose screeds and screeds of America, her ways and her people, their manners and their customs.

Superficial vaporings, but far better composed and built by far on firmer ground than the idle opinions of those few Americans who have gone to the vast, far stretching empire of the Slavs, and glibly vouchsafed their ex cathedra views thereon.

The dominions of Great Russia were spread from the Baltic east to the Japan Sea, and from above the Arctic Circle far south to the Caspian and the Black Sea and Lake Baikal in Siberia. They comprised eight million six hundred and fifty thousand square miles of varied territory, nearly three times that of the United States, and were peopled by heterogeneous people, numbering one hundred and eighty million, as estimated, for no census or even approximate count has ever been attempted.

There were the Finns and the Letts, the Lithuanians, the Jews, the Mordvinians, the Estonians, the Siberians, the Great Russians, the Little Russians, the Red Russians, and the White Russians of the Central Provinces, the Cossacks of the south, and the Tartars of the Caucasus; all with no conscious unity, no national identity, not a single common impulse or purpose or interest. In many instances, without a communion of language.

The total length of railways in 1917 was thirty-four thousand miles, or less than one-eighth of that of our country. Of these one hundred and eighty million Russians, nearly eighty per cent are moujiks, docile, patient serfs, liberated scarcely sixty years ago by Alexander II, and still shackled by the shackles of their serfdom, woeful ignorance, cowed spirit and afflicting poverty.

The remaining twenty per cent are survivors of the fading nobility and the bourgeoisie, or middle class, who have acquired wealth and consequent social rank without claim to nobility of birth. These last are hated with an intense, irrational hatred by the Bolsheviki.

The noble class, the Russian of Turgenev, supersensitive, highstrung, supercultivated, almost to the point of degeneration, is fast vanishing with the passing of the last vestige of the Romanoff regime, and soon will be a thing of the past. This intolerant caste for centuries had dwelt in idleness on great landed estates. It was as alien to the poor moujik as if of an entirely distinct race. I met a few of these highborn on the streets of Archangel, whence they had fled from the murderous Reds in the cities of Moscow and Petrograd. Elegant gentlemen they were, in all the glittering panoply of Imperial army officers, and manners the extreme in politesse; very pompous, extremely impressive. They did not conceal their contempt of the crawling moujik; he was a swine, and when the word was hissed in Russian, it sounded very swinish.

The serf and the highborn, the swaggering, objectionable bourgeoisie, the moujik and his animal ignorance, the intelligencia, and his superculture, each separated from the other by an abysmal unspanable gulf; and the various Russian races so dissimilar in thought and living, in customs, even in language, all nevertheless were kept in some semblance of cohesion by the brutal, disciplinary methods of the Tsar and the cooperating spiritual guidance of the Russian State Catholic Church, of which the Tsar was the Little Father.

San Francisco is as acutely conscious of national affairs in Washington, as New York, and more so. But this is because the finest transportation system in the world makes it possible to journey from one city to the other in a few days, and because every American is an ardent disciple of our great public press.

But Vladivostok knows nothing of Petrograd, and Petrograd knows little of Archangel, and in the little villages, where the people live, the world beyond is clothed in impenetrable mystery; for there are no railways to these villages. No news comes in, and if news came, there are few among the moujiks who could read it.

It is well to keep these things in mind when men speak of Russia, as if overnight it could formulate a concerted policy and engage in a purpose backed by preponderant control of the Russian people. Russia is not a nation, it is an immense, unwieldy empire, a giant of tremendous strength, with undreamt-of potentialities, capable of colossal deeds, but without authoritative, united control or direction; entirely unconscious of any national entity.

When Nicholas abdicated in March, 1917, it was an anxious world that viewed the experimental government of Prince Lvoff. Russia was an important ally, but she had made heroic sacrifices and had lost five millions of men; if she faltered now, the world might be lost. And there were rumors of a separate peace.

A few months after the downfall of the Tsar, Kerensky, as Premier, issued a manifesto expressing undying allegiance to the sacred cause of the Allied Nations, and shortly delivered to the army his famous Prikaz, which:

a. Abolished the penalty of death for disobedience of essential military discipline.

b. Abolished soldierly courtesy and the salute. Officers were henceforth to be known as tvarishi, comrades, and all social distinctions between them and the common soldier were abrogated.

c. Meetings of soldiers to discuss the conduct of military affairs were permitted.

Officers were simply unmanned of any effective authority. They were permitted to administer and instruct their organization, but all disciplinary measures were passed upon by a committee of soldiers, and so obedience to any order was a matter for ultimate ruling by such a soldier committee and not by an officer. This was democracy run riot, individual liberty gone stark mad. A few weeks after Kerensky took command, one million five hundred thousand Russian soldiers, grown weary of the tedium and the hazards of the front, quit the army and returned to their homes.

Thus by one foolhardy, ill-advised measure, an army became a rabble. Discipline, as essential to the military as blood is essential to sustain a physical body, vanished, and the collapse of Russia began with Kerensky.

Archangel, where the East comes abruptly face to face with the West

After the entry of the United States into the war in April, 1917, President Wilson was uneasy about Russia and her future course against the common enemy. Emissaries were therefore sent to learn of conditions first hand. Headed by the Honorable Elihu Root, as Ambassador Extraordinary, these reached Petrograd on the 13th June, 1917. Charles P. Crane, Cyrus H. McCormick of Illinois, and General Scott, the American Chief of Staff, accompanied Mr. Root. The emissaries met Kerensky, talked with several military and labor leaders, attended many banquets, made as many good speeches, and reported to the President in Washington on 12th August of the same year.

This report was made in confidence to the President, and even at the late date of the present writing, all requests to examine it have been denied by the State Department, on the grounds that "Divulgence is incompatible with the public interests."

But shortly afterwards, Mr. Root gave out an interview, which purported to express the views of the delegation: that they had come back with faith in Russia; faith in Russian qualities of character that are essential tests of competency and self government; faith in the purpose, the persistence and the power of the Russian people to keep themselves free.

Many American bankers, believing in Mr. Root, manifested kindred faith by the exchange of good American dollars for Russian rubles, despite the fact that the Russian government was hopelessly bankrupt and was showing an operating deficit of milliards of rubles.

General Scott visited the Russian front and witnessed the offensive which resulted in the taking of Kovel and Lemberg. He conferred with Generals Brussiloff, Korniloff, and Erdeli and their staffs, and reported to the American Secretary of War that Russia would stay in the war "if given even a part of the aid she asks."

Three months before the debacle, the Secretary of State, Mr. Lansing, assured the American people that Russia was stronger than she had been for some time, both from the government point of view and the military point of view.

The government point of view? The outstanding feature of the Russian Government "point of view" has always been the venal disposition of the High Command; the shameful, heartless, conscienceless corruption of persons in authority. Everyone knew this who knew Imperial Russia. At the trial of General Sukhomlinov, Minister for War, General Yanushkevitch, former Chief of Russian General Staff, testified that in the retreat from Galicia, during the summer of 1915, there was only one rifle for every ten soldiers. The soldiers in the rear had to wait until their comrades on the firing line were killed so that they might have their rifles. The Russians had no shells, and the Germans knowing this, set their guns two thousand yards off and shot down one helpless regiment after the other.

Many other examples of pitiful defenselessness could be cited at a time when the Allies loaned hundreds of millions of dollars to Russia for arms and military equipment, and Russia had these munitions, but far back of the front lines.

We have viewed Russian affairs as we have viewed Mexico, with American provincial eyes instead of attempting to judge from a Russian angle. Gladstone said that a nation guided by provincial statesmen was doomed for perdition, and, by reason of our provincialism, American statecraft striving to cope with Russia was hopelessly handicapped at the outset. This wholesale scandal and shameless corruption in high circles was typically Russian, an essential premise upon which to form a judgment of the Russian situation, but a premise totally unknown to persons unfamiliar with Russian character and Russian conditions.

Democracy assumes intelligence, but most important of all, self-control. Had we been familiar with the Russian people, is it likely that our State Department would have given such unstinted confidence to the dreamer, Kerensky? For like all countries where ignorance stifles the progress of struggling national life a strong unhesitant hand was needed to guide the nascent Russian democracy, and instead of resolution Kerensky presented oratory and by his Prikaz and vacillating policies rapidly lost his grip upon the army. General Korniloff attempted to rally the demoralized forces, restored the death penalty and strove to bring out of the chaos created by Kerensky, some likeness of coordination, but there was a division in adherence to the Premier and the General, and in the end both Korniloff and Kerensky failed. Probably no man could have succeeded; the seeds of destruction had germinated and struck root. It was too late.

The revolution of the Bolsheviks took place on 7th November, 1917, and in February following was announced the Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, whereby the provinces of Russian Poland, Courland, Lithuania, and Estonia came under German control, giving Germany an important Baltic littoral. Turkey, the ally of Germany, was to receive back all territory in Asia Minor occupied since the war, and in addition the districts of Kars and Erivan and Batum. Germany and Turkey controlled the Caucasus, the boundaries of which were to be restored as they existed before the Russian-Turkish War of 1877. During the civil war that followed in the Ukraine, the Germans occupied the port of Sevastopol, and the Austrians took Odessa. Germany got vast stores of guns and war material, thirteen thousand three hundred fifty miles of railway, more than one-third of the entire Russian rail system, a large amount of rolling stock, seventy-three per cent of Russian iron fields and eighty-nine per cent of her coal.

The war in the East was over, one hundred and forty-seven German and Austrian Divisions were released for the Western Front.

"Shall the military power of any nation or group of nations be suffered to determine the fortunes of peoples over whom they have no right to rule except the right of force?"

WOODROW WILSON—27th September, 1918.

III

OBJECTS OF THE EXPEDITION

It is said of the Bolsheviks, that they are a terrorist, minority party, rode to power by the seizure of every available machine gun in Russia and maintain their sway by the same forceful persuasion.

One of the intelligencia once told me, that of every hundred Russians, only two were Bolsheviks, and the remaining ninety-eight were cowed into submission by the methods of the desperado.

This, to enlightened, high-spirited America is a preposterous statement, but Russia is not America. Nor has she America's schools, nor America's great railways, nor the public press of America.

At Brest-Litovsk, Russia was stripped of nearly all war supply and munitions by the unsparing Germans, and what was left was seized by the belligerent Soviets.

Now, even in proud America, a resolute man back of a six shooter has been known to hold up an entire train load of people. And whether the Soviets are backed by the sanction of the masses, or whether as the Imperialists would have us believe, they are an unprincipled, bullying minority, they are in truth and fact the de facto government and represent the sovereignty of Russia in the comity of nations.

For six years Lenine and Trotsky have ruled, while the ministries of America, France, England and Italy have undergone complete transformation with the changing judgments of these troublous times, and now, begrudgingly, Russia; Russia of the Soviet Party, proletarian Russia, anarchistic, "nihilistic" Russia is given a seat at the international conference table of Lausanne, Great Britain has officially recognized the Soviets, and clamorous politicians in this country (even one statesman), are emphatically demanding recognition by the United States.

The Bolsheviks derived their inspiration from the Russian anarchist, Bakunin, an apostle of terror and violence. Bolshevik comes from the Russian word bolshinstvo, the majority. The name was used for the first time in 1903, when Nicolai Lenine split the Social Democratic party in two and assumed leadership of the majority. Lenine's real name was Zederblum, that of Trotsky, Bronstein.

The moving purpose of Bolshevism is to organize a great international revolution, affecting all countries. A revolution that will eradicate forever the hated capitalist class, and the despised small proprietors and entrepreneurs, known as bourgeoisie. Bolshevism is openly an enemy of democracy. It has no tolerance for any class save the proletarian. In the Bolshevik era, only the proletariat has any claim. Bolshevism is autocracy, autocracy of the proletariat. A ruthless autocracy that would utterly destroy every social group except this favored one.

Directly he assumed power, Lenine put into effect the Land Decree, which abolished the title of landlords to real estate and confiscated all landed estates, except the small holdings of the peasants. All employers of labor were suppressed, the six-hour day was established in industrial enterprises, and all employees were to have a voice in the management.

There is naught in this program which can be reconciled with German Imperialism, yet many statesmen and soldiers in Allied councils were convinced that an alliance existed between the Bolsheviks and Germany. But it is impossible to conceive of two more extreme opponents in political philosophy, for the Prussian Junkers believed devoutly in the divine commission of kings, as enunciated by the Kaiser himself; and the Bolsheviks, hating every suggestion of imperialism with an intense, raging hatred, threatened death to every king, and recognized, as qualified to rule or govern, none save the proletariat.

Only one tenet did Bolshevism and Prussian militarism have in common, i.e., they were both invincibly opposed to democracy. Both archenemies of political justice, as we Americans understand political justice.

The military leaders and statesmen at Berlin beheld with serious alarm the Revolution of November, 1917. They loathed the Bolsheviks and feared the effect of their insidious propaganda on the German masses. The German Chancellor, Von Bethmann, was obsessed with the fear of Bolshevism, and Ludendorff writes bitterly of the grave error in failing to crush the Soviet Party and to openly take sides with its opponents in Russia. He speaks of the lowered morale of the Eastern German Divisions; how several of them proved utterly worthless in the battles of France, as a consequence of coming in contact with the Bolsheviks; how the Bolshevik revolutionary ideas corroded the spirit of the people at home, and had more to do, than the military defeat, with the downfall of the German Government.

And the Soviet leaders returned the venom of Berlin with even greater virulency. They denounced the Brest-Litovsk agreement, stigmatizing it as: "The rape of Russia," and in their propaganda repeatedly expressed imperishable hatred of the German Imperialists. Lenine withdrew from the negotiations at Brest-Litovsk on 11th February, 1918, and refused to accede to the harsh demands of Germany. Thereupon, the Ukraine was immediately invaded, and on 1st March, the Germans occupied Kiev, the capital, holding a line to Reval on the Gulf of Finland, through Estonia, Pskov, Vilebsk and Mogilev. The helpless Russians could do nothing but submit, and under duress signed the treaty on 3rd March, 1918.

Still has it been affirmed by Allied statesmen time and repeatedly that the Bolsheviks were a willing party to the Brest-Litovsk pact, and that Moscow and Berlin were conspiring for the destruction of all Western civilization.

In his Fourteen Point address to Congress on 8th January, 1918, President Wilson expressed deep sympathy with Russia and enunciated Point VI as one of the cardinal principles for which the Allies fought:

VI. The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy, and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire. The treatment accorded Russia by her sister nations in the months to come will be the acid test of their good will, of their comprehension of her needs as distinguished from their own interests.

On 11th March, 1918, on the eve of its meeting to pass upon the question of the acceptance or rejection of the Brest-Litovsk terms, the President sent a message of friendship to the all Russian Congress of Soviets, which contained this pledge:

Although the government of the United States is unhappily not now in a position to render the direct and effective aid it would wish to render, I beg to assure the people of Russia, through the Congress, that it will avail itself of every opportunity to secure for Russia once more complete sovereignty and independence in her own affairs and full restoration in her great role in the life of Europe and the modern world. The whole heart of the people of the United States is with the people of Russia in the attempt to free themselves forever from autocratic government and become masters of their own life.

Many contend that if the Allies had stood by the de facto government of Russia, as President Wilson's words gave promise of doing, the disastrous treaty would never have been accepted.

Questions have been addressed to the then American Secretary of State asking: Did the administration know at the time of the Brest-Litovsk negotiations:

1. That the Soviet government represented by Lenine and Trotsky was opposed to the projected treaty and signed it only because of the physical impossibility of resisting German demands unless some of the Allies came to its aid?

2. That Lenine and Trotsky gave a note to Colonel Raymond Robbins of the Red Cross, stating to the President of the United States that they were opposed to the treaty and would not sign if the United States would give food and arms to the Russians?

The reply of Mr. Lansing was that answers to these questions were not compatible with the public interest.

On 12th December, 1918, Senator Johnson asked this question in the United States Senate:

Is it true that the British High Commissioner, sent to Russia after the Bolsheviki revolution because of his knowledge and experience in the Russian situation, after four months in Russia, stated over his signature that the Soviet government had cooperated in aiding the Allies, and that he believed that intervention in cooperation with the Soviet government was feasible as late as the fifth of May, 1918?

No spokesman for the administration, or anyone else, ever answered or attempted to answer this question.

After Brest-Litovsk, it was generally believed that the ambitions of Germany in Russia were:

1. To recruit her war wasted divisions from the great number of Austrian and German prisoners in Russia.

2. To exploit the great natural resources of the Ukraine, Courland, Lithuania and Estonia.

3. To align on her eastern frontier buffer states from Finland to the Caucasus with Persia as the last link in the chain.

4. To seize great stores of war munitions at Archangel and Vladivostok.

There was also some credence in the rumor that Germany sought to establish submarine bases at Murmansk and Petchenga in Finland.

Murmansk, on the Kola Peninsula, is the only port of North Russia not closed for nearly half the year. During the months of winter, from December until the middle of June, Archangel, Kem, Onega and Kandalaksh on the White Sea are sealed by effective barriers of ice, and even Petrograd, several hundred miles further south on the Baltic, is closed until late in April. But the Cape current of the Gulf Stream swings around the northern coast of the Kola Peninsula, and at Murmansk there is an excellent natural harbor, which is always open, with thirty-two feet of water in shore, and a high coast line, giving splendid protection against storm. From this valuable ice free port, the Murman railway extends three hundred miles to Kem and continues through Petrozavodsk on the west shore of Lake Onega, six hundred miles further to Petrograd.

The completion of this, the most northern railroad, is a triumph of imagination and courage and invincible resolution. The Russian engineer, Goriatchkovshy, inspired by the necessity of his country having a means of inlet for munitions and supplies during the war (for the Trans-Siberian railway could carry only about one-seventh of such supplies), laid the tracks over seemingly bottomless tundra and conquered in the face of most disheartening discouragements.

A great number of German prisoners and one hundred thousand Russian laborers worked to complete the heroic enterprise. Experts predicted that with the melting of the ice in spring, the tracks would disappear in the marshes, but Goriatchkovshy had reckoned with the elements. The Murman railway is operating today. It has a hauling capacity of thirty-five hundred tons a day, the maximum handling facilities of Murmansk port, and many a lonely soldier, snowbound in North Russia, during the tragic winter of 1919, has the Murman railway and its creator, Goriatchkovshy, to thank for the messages from far off America, that came to Murmansk and were brought to Archangel by Obozerskaya on the Vologda railway, and then relayed by droshky and the faithful Russian pony to a solitary sentinel post somewhere in the great white reaches of the interior.

Very close to the Murman road is Finland, which, because of its remoteness from the Russian capital, had always exercised a limited autonomy, and following the Kerensky Revolution of March, 1917, announced by the action of the Finnish Diet, its complete independence.

A civil war between Red Guards and White Guards for the control of the government followed. It was no secret that from the beginning of the European war the sympathies of the Finns were with Germany, and now at the outbreak of this internal conflict in Finland, Germany aligned with the White Guards against the revolutionary Reds who were supported by the Bolsheviks.

At the beginning of April, 1918, three regiments of German rifles, two batteries and three battalions of Jagers, under General von der Goltz, landed at Hanko, and, cooperating with the White Finns, suppressed the revolutionists, took possession of the port Viborg and were in control of railway communication to Petrograd. But this small expeditionary force never left the southern part of Finland, and in August, when every German was needed in France, the greater part of it left for the Western Front.

The campaign in Finland had no effect on the course of the war. Its significance was unduly magnified by both sides.

It was a firm conviction in Allied Councils that the Germans had immense forces in Finland, while the German Imperial Staff thought that the insignificant hundreds that the British landed at Murmansk in April, almost at the same time that the Germans entered the south of Finland, were in large numbers, perhaps several Divisions.

Thus there existed a blindman's buff in Finland; both Commands in startling ignorance of enemy salient facts, which is often the case in the game of war where "uncertainty is the essence"; each supposed the other was actively engaged in "recreating an Eastern Front," which, in concrete application, meant the recruiting of hundreds of thousands of Russians to press on from the East and fill in the war-wasted gaping ranks of Germany or the Allies.

To effect this object and gain access to the interior of Russia, the Murman railway, therefore, assumed a momentous significance; but in truth the "Eastern Front" remained a figment of the military imagination. Russia had poured out the life blood of her sons in the Allied defense till she staggered weak and exhausted, so spent that she swayed in a moral lethargy from which nothing on earth could arouse her, and those Russian soldiers who survived returned to their villages or else were conscripted for the Red army by the amazingly effective methods of Trotsky.

Still, in the spring of the year 1918, the situation in Finland appeared so fraught with grave potentialities of decisive consequence, that on 27th May, the Allied military attaches of Italy, France, England and the United States met at Moscow and unanimously agreed that these nations should intervene in the affairs of Russia.

Shortly after this, the Supreme War Council at Versailles decided in favor of intervention in the northern Russian ports, and the United States gave its consent.

Brigadier General F. C. Poole had been in Petrograd in command of the technical war mission of the British in Russia. Thoroughly familiar with Russian character and Russian conditions, he was chosen to command the Northern Expedition.

The advance party of the Americans landed in Archangel on 3rd August, 1918. On the same day, this statement was cabled to the Russian Ambassador from the State Department at Washington:

In the judgment of the government of the United States, a judgment arrived at after repeated and very searching considerations of the whole situation, military intervention in Russia would be more likely to add to the present sad confusion there than to cure it, and would confuse rather than help her out of her distresses, as the government of the United States sees the present circumstances, therefore military action is admissible in Russia now only to render such protection and help as is possible to the Czecho-Slovaks against the armed Austrian and German prisoners who are attacking them, and to steady any efforts at self-government or self-defense in which Russians themselves may be willing to accept assistance. Whether from Vladivostok or from Murmansk and Archangel, the only present object for which American troops will be employed will be to guard military stores which may be subsequently needed by Russian forces, and to render such aid as may be acceptable to the Russians in the organization of their own defense.

The importance of guarding the Arctic ports from the Germans passed with the signing of the Armistice, but armed intervention continued, and the most sanguinary battles in North Russia were fought in the dark winter months that followed.

When the last battalion set sail from Archangel, not a soldier knew, no, not even vaguely, why he had fought or why he was going now, and why his comrades were left behind—so many of them beneath the wooden crosses. The little churchyards and the white churches and the whiter snow! Life will always be a crazy thing to the soldier of North Russia; the color and the taste of living have gone from the soldier of North Russia; and the glory of youth has forever gone from him.

It is a fearful thing to contemplate the deliberate taking of a life. All consciousness recoils at the dreadful, irretrievable consequences of murder; yet when nations engage in extensive killing, there is no malice in the act on the part of individuals. Killing then has an impersonal character and becomes an heroic contemplation.

In Western trenches, the enemy was called "Jerry" in a spirit of grotesque comradery and sportsmanship, and the finest soldiers had little hatred in their hearts for those across the twisted, shell gashed acres, who sought to maim and kill them, but with no malice aforethought.

The mildest men, and men of highest culture and intelligence, recently made a profession of killing, and could practice their newly found profession with keen, cold, ghoulish precision and the comprehensive analysis of trained minds. War is not murder, and the business of killing loses its infamy and much of its obscenity by the united impulse of millions striving with selfless purpose, pure devotion and heroic sacrifice for a nation's goal. War shears from a people much that is gross in nature, as the merciless test of war exposes naked, virtues and weaknesses alike. But the American war with Russia had no idealism. It was not a war at all. It was a free-booter's excursion, depraved and lawless. A felonious undertaking, for it had not the sanction of the American people.

During the winter of 1919, American soldiers, in the uniform of their country, killed Russians and were killed by Russians, yet the Congress of the United States never declared war upon Russia. Our war was with Germany, but no German prisoners were ever taken in this lawless conflict of North Russia, nor, among the bodies of the enemy killed, was there ever found any evidence that Germans fought in their ranks or sat in the councils of their Command. And in the conduct of the whole campaign there was no visible sign of connection between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers.

The war was with the Bolsheviki, the existing Government of Russia, and a few weeks after the arrival of American troops in Archangel, Tchitcherine, Soviet Commissioner for Foreign Affairs, handed a note to Mr. Christiansen, Norwegian diplomatic attache, which was delivered to President Wilson, in which the Bolsheviks offered to conclude an armistice upon the removal of American troops from Murmansk, Archangel and Siberia.

This note was ignored. The Soviets had no recognition as the government of Russia, and there was no "war" in Archangel or Murmansk or Siberia.

No war, but in the province of Archangel, on six scattered battlefronts, American soldiers, under British command, were "standing to" behind snow trenches and improvised barricades, while soldiers of the Soviet cause crashed Pom Pom projectiles at them, and shook them with high explosive and shrapnel, blasted them with machine guns, and sniped at any reckless head that showed from cover.

The objects of the Expedition, as defined in a pamphlet of information given out by British General Headquarters, in the early days of the campaign, were:

1. To form a military barrier inside which the Russians could reorganize themselves to drive out the German invader.

2. To assist the Russians to reorganize their army by instruction, supervision and example on more reasonable principles than the old regime autocratic discipline.

3. To reorganize the food supplies, making up the deficiencies from Allied countries. To obtain for export the surplus supplies of goods, such as flax, timber, etc. To fill store ships bringing food, "thus maintaining the economical shipping policy."

The Bolshevik government is entirely in the hands of the Germans, who have backed this party against all others in Russia owing to the simplicity of maintaining anarchy in a totally disorganized country. Therefore, we are definitely opposed to the Bolshevik-cum-German party. In regard to other parties, we express no criticism and will accept them as we find them, provided they are for Russia, and therefore "out for the Boche." Briefly, we do not meddle in internal affairs. It must be realized that we are not invaders, but guests, and that we have not any intention of attempting to occupy any Russian territory.

Later, this proclamation was issued to the troops by the military authorities:

Proclamation: There seems to be among the troops a very indistinct idea of what we are fighting for here in North Russia. This can be explained in a few words. We are up against Bolshevism, which means anarchy pure and simple. Look at Russia at the present moment. The power is in the hands of a few men, mostly Jews, who have succeeded in bringing the country to such a state that order is non-existent. Bolshevism has grown upon the uneducated masses to such an extent that Russia is disintegrated and helpless, and therefore we have come to help her get rid of the disease that is eating her up. We are not here to conquer Russia, but we want to help her and see her a great power. When order is restored here, we shall clear out, but only when we have attained our object, and that is the restoration of Russia.

At about the same time that this proclamation was spread among British soldiers in Russia, the Inter-Allied Labor Conference met in London and sent an expression "of deepest sympathy to the labor and socialist organizations of Russia, which having destroyed their own imperialism, continue an unremitting struggle against German Imperialism."

Still later, there was broadcasted among the soldiers, headed "Honour Forbids," an exposition of the campaign by Lord Milner, British Secretary of State for War, who defined its objects:

1. To save the Czecho-Slovaks. Several thousand of which under command of General Gaida were believed to be strung along the Siberian railway from Pensa to Vladivostok.

2. To prevent the Germans from exploiting the resources of Southeastern Russia.

3. To prevent the northern ports of European Russia from becoming bases for German submarines.

When these objects were accomplished, the British statesman declared that to leave Russia to the unspeakable horrors of the Bolshevik rule would be an abominable betrayal of that country, and contrary to every British instinct of honor and humanity.

During the winter months of 1919, when Senator Johnson was demanding in the United States Senate the reasons for the American war with Russia, Senator Swanson, of Virginia, of the Foreign Relations Committee, and one of the spokesmen of the administration replied that American troops were needed to protect great stores of Allied ammunition at Archangel, and to hold the port until terms of peace were signed with Germany. That Germany wanted Archangel to establish a submarine base there, and it would be cowardly to forsake Russia.

During the peace negotiations at a meeting of the Council of Ten at Quai D'Orsay, on 21st January, 1919, President Wilson, in discussing the Russian problem, stated that by opposing Bolshevism with arms the Allies were serving the cause of Bolshevism, making it possible for the Bolsheviks to argue that imperialistic, capitalistic governments were seeking to give the land back to the landlords and favor the ends of the monarchists. The allegation that the Allies were against the people and wanted to control their affairs provided the argument which enabled them to raise armies. If, on the other hand, the Allies could swallow their pride and the natural repulsion which they felt for the Bolsheviks, and see the representatives of all organized groups in one place, the President thought it would bring about a marked reaction against Bolshevism.

Mr. Lloyd George, earlier in the discussion, said that the mere idea of crushing Bolshevism by a military force was pure madness. Even admitting that it could be done, who would occupy Russia? If he proposed to send a thousand British troops to Russia for that purpose, the armies would mutiny.

It was agreed by the Council of Ten, then Four, that President Wilson should draft a proclamation inviting all organized parties in Russia to attend a meeting in order to discuss with the representatives of the Allied and Associated Great Powers the means of restoring order and peace in Russia. Participation should be conditional on a cessation of hostilities. This meeting was to take place on Prinkipos Island in the Sea of Marmora.

The President issued the proclamation, but the French were opposed to it and communicated with the Ukrainians and the other anti-Soviet groups in Russia, to whom, as well as to the Bolsheviks, the proposal was addressed, telling them that if they refused to consider the proposal, the French would support them and continue to support them, and not allow the Allies, if they could prevent it, to make peace with the Russian Soviet government. The time set for the gathering at Prinkipos was on 15th February, 1919, but no party acted in a definite way and it never took place.

At the time of the Bolshevik revolution, the national debt of Russia was 700,000,000,000 of rubles. The interest and sinking fund charge was 4,000,000,000 of rubles annually. There was a deficit in the annual budget of one milliard. Of this total debt, 15,500,000,000 of rubles were owing to France, and France felt the prospective loss far more than any of the other creditor nations, for the French government had encouraged the purchase of rubles by her nationals, and these now nearly worthless securities were held by the peasants from Artois to Gascony.

The Murman and Vologda railways

Like the Prinkipos proposal, nothing came of a Soviet proposal for peace which was brought to the Paris Peace Conference by an emissary dispatched by the American commissioners to obtain from the Bolsheviks a statement of the terms upon which they were ready to stop fighting. This was in February, after the desperate situation of the troops near Archangel was brought to the attention of the Conference by the Allied Military commanders. These Soviet peace terms were approved by Colonel House at Paris, who referred them to the President, "but the President said he had a one track mind and was occupied with Germany at the time, and could not think about Russia, and that he left the Russian matter all to Colonel House."

The sessions at Versailles adjourned without day [delay?]. If we were at war with Russia in 1919, we are still at war with her. Peace was never made with Russia; and peace never will be made in the hearts of those plain people in the Vaga and Dvina villages, who saw their pitifully meager possessions confiscated in the cause of "friendly intervention," their lowly homes set ablaze and themselves turned adrift to find shelter in the cheerless snows.

Friendly intervention? All too vividly comes to mind a picture during the Allied occupation of Archangel Province while the statesmen at Paris pondered and deliberated in a futile attempt to find dignified escapement from this shameful illegitimate little war. Military necessity demanded that another village far up the Dvina be destroyed. As the soldiers, with no keen appetite for the heartless job, cast the peasants out of the homes where they had lived their uncouth, but not unhappy lives, the torch was set to their houses, and the first snow floated down from a dark, foreboding sky, dread announcer of the cruel Arctic winter. Within these crude, log walls, now flaming fire, had they lived, these gentle folk, as their fathers had lived before them, simple, unsophisticated lives, felicitously unmindful of petty vanities and corroding ambitions. Who can say theirs was not the course of profoundest wisdom? For had they not known in these humble homes those candid pleasures, the only genuine ones, those elemental joys, springing like hope and the unreasoning urge of life from the heart of humanity, oblivious of all artificial environment? Here in these mean abodes had they tasted the ecstasy of love, known the full poignancy of sorrow, wept in natural grief and laughed loud with boisterous, unrestrained, rustic laughter. In a corner hung the little ikon, where the lamp burned on holidays, and they worshipped their God with a devotion so genuine, so deep and reverent, that only a fool could scoff.

Outside now, some of the women ran about, aimlessly, like stampeded sheep; others sat upon hand fashioned crates, wherein they had hastily flung their most cherished treasures, and abandoned themselves to a paroxysm of weeping despair; while the children shrieked stridently, victims of all the visionary horrors that only childhood can conjure.

Most of the men looked on in spellbound silence, with a dumb, wounded look in their eyes. Poor moujiks! They did not understand, but they made no complaint. Nitchevoo, fate had decreed that they should suffer this burden.

Why had we come and why did we remain, invading Russia and destroying Russian homes? The American consul at Archangel sent us the Thanksgiving Day message of our President, rejoicing in the Armistice, and the end of the carnage of war. But the consul announced that we would remain steadfast to our task until the end. The end! What was the end?

The British General Finlayson of Dvina Force said: "There will be no faltering in our purpose to remove the stain of Bolshevism from Russia and civilization." Was this, then, our purpose through the dismal night of winter time, when we burned Russian homes and shot Russian people? And was this still our purpose when we quit in June with Bolshevism strengthened by our coming, and more than ever before the government of Russia?

The only stain was the stain of dishonor we left in our retreating path. But a deep, red, burning stain of shame is on the foreheads of those men who sit on cushioned seats in the high places, chart armed alliances in obscure international commitments, and, with careless gesture of their cigar, send other men to some remote forsaken quarter of earth, where there is misery and suffering, and hope dies, and the heart withers in cold, black days.

Now it was of small concern to Ivan whether the Allies or the Bolsheviks won this strange war of North Russia. What he heard was some vagary of "friendly intervention"; of bringing peace and order to his distracted country. What he saw was his village a torn battle ground of two contending armies, while the one that forced itself upon him, requisitioned his shaggy pony, took whatever it pleased to take, and burned the roof over his head.

He asked so little of life, this gentle moujik, with his boots and his shabby tunic, and his mild, bearded face, only to be left alone. In peace to follow his quiet ways, an unhurrying, unworrying disciple of the philosophy of nitchevoo.

"I consider it my duty to inform you in plain language that unless considerable reinforcements are sent before the end of October, the military situation both at Archangel and the Murman Peninsula will, in my opinion, become very serious."

ADMIRAL KEMP, in command of British warships at Murmansk, to the Admiralty, 26th August, 1918.

IV

THE PLAN OF CAMPAIGN

The Province of Archangel stretches from the Norwegian frontier across the Arctic Ocean east of the Ural Mountains of Siberia. It includes the Kola Peninsula, which lies well north of the Arctic Circle, and the further-most point south is below sixty-two degrees latitude. The total area is six times that of the average American state.

It is a poverty distressed and cheerless, destitute region, which, during the reign of the Romanoffs, like Siberia, was often a place of exile and asylum for political dissidents. War accentuated the poverty of the province, and the only remanent sign of former industry is at the port of Archangel, where large timber mills, owned mostly by British capital, line both sides of the harbor.

The port was founded by Ivan the Terrible during the Sixteenth Century, and ever since then has been a British trading post. At Onega, Kem and Kamdalaksh on the White Sea, there is, or was, before the war, some small traffic in timber products, furs and flax. But this commerce is of small consequence. Prenatally, Archangel was destined for pauperism, for it lies in the far north, where life is poor and hard struggling, and there is little soft sunshine to woo riches from the earth. Nor are treasures concealed beneath its sear and barren surface. The curse of sterility taints the air, and it was never written in the Divine Plan that man should dwell in this fortuneless, forsaken region. He was banished there, or driven by the pitiless pursuit of his own misdeeds. For nearly half of the year, the White Sea is an impenetrable ice barrier, and then communication with the world beyond can be had only through the Murman railway to the far north port of Murmansk.

In the city, the East comes abruptly face to face with the West. The exotic colors of the great domed cathedral were brought from ancient Byzantium, when the Greek church was made the faith of his country by Vladamir; and bearded, sad-faced priests, with their black robes, glide through the streets like nether spirits, and the mysticism of the ancient, mystic East.

This is the native atmosphere of Archangel, and it will not be in a generation that the city will, without consciousness, take on the soft adornments and the practical utilities of Occidental civilization. The glaring electric lights, the incongruous, modern buildings and the noisy tramway that clangs down the street—these do not belong to Archangel. They are a profane encroachment on her ageless, dreaming tranquillity and eternal repose; her enigmatical, perhaps profound philosophy of nitchevoo.

Fundamentally, Archangel is a primitive center of primitive beings. Instinctively, it is a dirty hole. Hopelessly, it is a filthy place, where noxious stenches greet the nose and modern sanitation is unknown.

In the days of peace, there were perhaps three hundred fifty thousand people in the province, and sixty thousand of them dwelt in Archangel. The only other cities of importance are Pinega, with three thousand persons, some one hundred miles to the east, and Shenkurst, two hundred miles south on the Vaga River, where there were four thousand. But as a whole, the inhabitants are moujiks, dwelling in little villages of two or three hundred log huts, that in structure and design bear close resemblance to the cabins of our frontier civilization.

About these villages, the peasants have cleared the forest for a few hundred yards, and in the brief, hot months of the midnight sun, they raise meager crops of wheat and flax and potatoes. When winter comes, they are continually indoors, gathered about great ovens of fireplaces, and long through the dismal, cold, black days they sit and dream, or merely sit. They are unsophisticated folk, incredibly ignorant, but gentle, quiet mannered, sweet natured souls, despite a harsh, uncouth life; and very responsive to kind treatment.

Cholera visits them with recurrent, devastating plagues, and takes fearful toll, for they live in the midst of nauseating squalor, with total disregard to sanitation, and drink from surface wells, that in the sudden spring are reservoirs of sewage and all manner of obscene refuse.

All along the rivers and roads of the interior, at intervals of five to ten miles, are strung these moujik villages.

There is, among these people, no agriculture as we practice it in our country, with a set of prosperous looking farm buildings for the cultivation of two hundred and five hundred broad, fertile, American acres. In Russia, I never saw more than five hundred cleared acres for an entire village.

Yet, from these small, unfecund patches, the peasants, somehow, wrung the means of sustaining life, and those who toiled in the fields divided the scanty harvest with the aged and the weak, and the children who were fatherless: so that there was no mendicancy among the moujiks, and no affluence either.

There are two railways in Archangel Province, the Murman road, which begins at Murmansk on the Arctic Ocean, extends south to Kem through Petrozavodsk, and forms a juncture fifty miles east of Petrograd with the Trans-Siberian, nine hundred miles from the point of beginning; and the Archangel-Vologda railway, which reaches from Archangel four hundred miles south to Vologda, where the Siberian road comes in from Viatka on the east and leads to Petrograd. Both railways have the standard five feet gauge single track. During the winter of 1919, the Murman road, with a theoretical capacity of thirty-five hundred tons, had an actual hauling capacity of only five hundred tons a day, and its rail connections were in very poor condition and badly in need of repair. The Vologda road had a single track, but with sidings every five miles. Both roads had obsolete rolling stock, rickety, tumbled down cars and wood-burning locomotives of a type used in our country fifty years ago.

During the war with Russia, the Allies, with a medley force of friendly Russians, British, Canadians, French, a battalion of Serbians and a battalion of Italians, held the Murman railway as far south as sixty miles beyond Soroka, which is a little south of Archangel and two hundred miles to the east.

There were no Americans on this Murman railway front, except two companies of railway transportation troops, which reached Russia in April and were the last to leave in July, 1919.

Patrols with webfoot snowshoes went forth on the snow

Beyond the Murman and the Vologda railways, the only other highway to the interior is the Dvina, a dirty colored, broad spreading river, which from its beginning, as the Witchega, at the base of the Timan Range in Vologda province, follows a swift flowing course one thousand miles northwest to the sea at Archangel.

Sometimes, when its banks are low and it sprawls out in play, its waters glide noiselessly with a look of gentleness and peace, and the Dvina puts one in mind of our Mississippi; but usually its cold depths are freighted with grave mystery and melancholy foreboding, and then it is the spirit of Russia, hurrying by forested shores and high, desolate bluffs, where a mill, near a huddle of soiled log houses, flaps its clumsy, wooden wings, and a white church, with fantastic minaret, rears aloof, chaste and austere, in the midst of squalor.

During the period of navigable water, in the days of peace, the Dvina was plied by steamers and barges and watercraft of every description, but the freeze commences in early November, and then, until the last days of May, its waters have become a bed of thick ice.

Then, except by the Vologda railway, the only method of transportation between Archangel and the interior is by sledges, drawn over the snow by little shaggy ponies that can perform miracles of labor and seem impervious to the terrible, cold winds. These ponies are the embodiment of the moujik temperament, docile and mild mannered, very patient and long suffering, and never resentful of the most severe chastisement.

The whole province is a plain of low, gentle slopes, covered with small fir trees and several varieties of dwarfed pine. A long, dormant season and the severity of winter preclude any luxuriant, ligneous growth. Even the underbrush is sparse and thinly scattered, and commercially, about the only value of the Archangel forests is for the manufacture of pulp. The bottom of this spindly pine woods is covered with a tundra. Sometimes, there are patches of waist deep water, and in other places, a morass that seems bottomless.

Such is the character of all the North Russian forests. The natives tell stories of men, unfamiliar with the country, who have lost their way and floundered in these treacherous marshes until they passed from sight without a sign of their passage.

During the rains of fall, and when summer bursts upon winter, in June, is the season of rasputitsa. The wagon roads then are sloughs of deep mire, and little travel is attempted. The first snow falls in November and gradually mounts, until in January it has a uniform height of three feet, except in the open places where there are great drifts much higher. No thaw comes until late February, and so moving for any distance on foot is impossible without skis or snowshoes. Cold follows the snow, gradually increasing in intensity until there are January days of forty-five and fifty degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

When the wind is high and the air filled with great, white blasts, this cold of Russia presses on the diaphragm like a ponderous weight and breathing becomes a gasping effort. In the depth of winter, the sun is banished, and during the latter part of December, only a few hours of pale, anemic glimmering separates the black Arctic night; a shadowy gloaming, like shortlived, desert twilight.

Splendid, fighting men were made weak cowards by the cumulative depression of the unbroken, Russian night and its crushing influence on the spirit; for the severest battles of the campaign were fought during the cold, black months of winter time.

Preparations for opening hostilities in the war with Russia were made in April, 1918. The Allied Supreme War Council had been alert to the presence of German troops in Finland and their fanciful menace to the Murman railway; and in the quiet harbor of Murmansk, British and French battleships had been idling purposelessly since early spring. In April, one hundred fifty Royal Marines landed from the British ships and were followed in a few weeks by four hundred more, also a landing party of French sailors. On 10th June, the United States warship, Olympia, appeared at Murmansk, and one hundred American bluejackets disembarked. These Allied forces penetrated down the Murman railway to Klandalaksh, some two hundred fifty miles south, and, in addition to holding Murmansk, seized the port of Petchenga on the coast of Finland.

Then the scene of intervention shifted southward, and on the 1st August, General Poole, with a party of five hundred fifty French, British and a few American marines, escorted by a British cruiser, a French cruiser and a trawler fleet, attacked Archangel, which, after a bombardment, was surrendered next day by the weak Bolshevik rear guard.

The main body of the enemy had carried with them far up the river to Kotlas and down the railway to Vologda, rations, rifles, guns and ammunitions, American manufactured. Likewise, they had seized and carried off nearly all available means of transportation; and when the Allied troops examined the vast storehouses in the harbor and at Bakaritza, they found that the Bolsheviks deliberately, systematically and with great thoroughness had stripped the shelves of every conceivable thing of value. If the object of the Archangel Expedition was to safeguard the vast munitions and stores there, it had failed signally and at the outset.

Still the enemy had fled, for, by some occult form of necromancy the Bolsheviki had now become "the enemy," and it is a major premise of the military that a fleeing enemy must always be followed up. Small heed that little was known of the strength or disposition of the retiring army. They had fled. Two forces were immediately dispatched in pursuit, up the river and down the railway; and, to augment the strength of the invaders, new troops were sent from Europe.

The 339th American Infantry arrived at Archangel on 4th September, 1918. It was composed of Wisconsin and Michigan men, mostly the latter; men from our farms and from our cities, who had been drafted for war against Germany.

Like most of our civilian soldiers, they had no exuberant ecstasy for the grim business ahead, but still possessed a remarkable appreciation of the war and its deep significant issues. And they had a quiet courage that was good to see, and a quiet resolution shorn of sentimental heroics to give their lives for their country if the sacrifice was necessary. Not one of them was deeply agitated by the emotion of "Making the world safe for Democracy," which is the desiccated war cry of the academician and never could reach the heart depths of any people; but they did feel in some vague, yet definite way, that a soulless military system, which had trampled brutal, iron-clad boots through the gentle fields of Belgium, might some day carry its hateful spate to the Michigan village or green-hilled Wisconsin farm, where an old lady with spectacles sat behind the window of a white cottage, and near lilac bushes growing fragrant in the lane a wholesome faced girl waited.

These soldiers of Russia were of the same type as our men who fought in France—no better and no worse; another way of saying that they were the best soldiers in the world. They were all drawn from the Eighty-fifth Division of the National Army, and came from all the races and shades and grades and trades of our many colored American society.

Many of them had had only a few weeks of crowded military training, and were still civilians in physique and bearing. Most important of all, they were civilian in mental constitution.

With the 339th Infantry, came the 337th Field Hospital Company, the 337th Ambulance Company, and the 310th Engineers, a splendid, upstanding, competent battalion, that in the approaching ordeal upheld the best in our American traditions, showed extraordinary power of adaptitude, extraordinary resourcefulness, no matter the difficulties, were ever cheerful and undaunted, and altogether splendid.

Roughly, the entire force of the Americans aggregated forty-five hundred men. It was augmented about a month later by five hundred replacements, snatched here and there from the infantry companies of the Eighty-fifth Division in France.

That September day the Americans landed at Archangel, and the fagged engines of the troop ships Somali, Tydeus, and Nagoya came to rest, those who looked from the decks breathed in the oppressive air a haunting presentiment of approaching evil.

Halfway from camp at Stoney Castle, England, five hundred of the little company had been stricken with the dreaded Spanish influenza. Eight days out at sea, all medical supplies were exhausted, and conditions became so congested in the ships' quarters that the sick, running high fever, were compelled to lie in the hold or on deck exposed to the chill winds.

At Archangel, there was little improvement. Soldiers were placed in old barracks, there they lay on pine boards. They had insufficient bedding, and for warmth had to keep on their clothing and boots. In this way many died and many more were enfeebled for many months, but "stuck it" with their companions and went to the front.

Had the Fates placed a curse on the Expedition from the beginning?

There was an air of inscrutable haunting sorrow in the lowering skies, glinted limpid with a sinister, bronzed light from a sun that flamed to crimson death among the dark trees over the bay.

Across the harbor projected the tiny red roofs of the city, the venerable cathedral, ghostly with great white dome, grotesque fantastic spires and minarets, garish in the fading light with startling pigments of green and gold. A mournful stillness brooded over a scene weird and alien to the men from far off Michigan and Wisconsin, who had a feeling that they had left behind forever the stage of tedious factory days and prosy farm life, and moved to another sphere, shrouded in mystery, filled with unparalleled, dread adventure.

Besides the American regiment, there was a British brigade of infantry nearly the same strength as the Americans, in the main composed of Companies of Royal Scots, most of them catalogued by the War Office as Category B2 men; unqualified for the arduous, exhausting tasks of an active field campaign, but fit enough to safeguard stores in Archangel, "light garrison duty."

Many wore the bronze wound stripe, and many had two and even three of these honorary decorations. These war-tired soldiers, wearied to the point of cruel exhaustion, had given freely and without stint of their body on the Western battlefields for King and Country; but the great Empire was backed to the wall and fighting for her life in an insatiable conflict, she exacted the last draining dregs of their gasping strength. That these "crocked" Category B men performed prodigies of fortitude and miracles of endurance, and acted deeds of stirring, spiritual courage in this war of the Far North is a permanent tribute to a manhood that England breeds, and imperishable glory to British arms.

The French sent eight hundred and forty-nine men and twenty-two officers, a battalion of the 21st Colonial Infantry, two machine gun sections and two sections of seventy-five millimetre artillery.

On the railway front, there was an armored train, with one eighteen pounder, one seventy-seven millimetre and one hundred fifty-five millimetre Russian naval howitzer. Then came early in the campaign the Sixteenth Brigade Canadian Field Artillery consisting of the 67th and 68th Batteries, each with six eighteen pounders and tough gunners seasoned and scarred by four years of barrages and bombardments in France, rather keen for the adventure of North Russia while the fighting was on, and thoroughly "fed up" when there was a lull in the excitement.

These Canadians, in peace, had probably been kindly disposed farm folk, gathering the rich bronzed harvests of Saskatchewan fields.

But four years of war had wrought a transfiguration of many things and no longer did life have its exalted value of peace times. No, life was a very cheap affair, but, cheap as it was, its taking often made exhilarating sport. At the end of a battle these quiet Saskatchewan swains passed among the enemy dead like ghoulish things, stripping bodies of everything valuable, and adorning themselves with enemy boots and picturesque high fur hats, with abounding glee, like school boys on a hilarious holiday.

Yet there was nothing debased or vicious about these Canadians. They were undeliberate, unpremeditated murderers, who had learned well the nice lessons of war and looked upon killing as the climax of a day's adventure, a welcomed break in the tedium of the dull military routine. Generous hearted, hardy, whole-souled murderers; I wonder how they have returned to the prosy days of peace, where courage counts for little, and men are judged not by the searching rules of war, but by the superficial standards of secure being; and living is soft and slow, an affair of rounding chores, with few stirring moments to illumine the dull routine of most of us.

At the outset, the Canadians and a few inaccurate Russians were our only artillery. Two months after the commencement of the campaign, two Four Point Five howitzers, with British personnel, joined the Allied Forces, and there were several airplanes, considered obsolete for use in France, but good enough for the Arctic sideshow.

The air pilots were daring and courageous men, but, besides being hopelessly handicapped by defective machines, they complained that the forests of North Russia made definite discernment of the ground a very difficult thing. The facts are that they dropped several bombs on our own lines, and twice with tragic disaster. There was never any apparent reason to believe that the airplanes caused the enemy even passing uneasiness, but we were always agitated as their menacing drone approached, always grateful when they trailed off to distant skies.

The complete combat command of the Commanding General of the Allied North Russian Expedition at the outset of the campaign was then:

One regiment of American Infantry,

One brigade of British Infantry,

One battalion of French Infantry,

Two sections of French Seventy-Fives,

Two sections of French machine gunners,

One brigade (487 men) Canadian Field Artillery,

One armored train,

One 155 millimetre and

One 77 millimetre Russian howitzers.

There were a few groups of Russian Infantry with the Allied troops, but at the outset these did not number over three hundred men. In all, there were approximately nine thousand five hundred combat troops.

With this force, the Allied Commander proposed to engage in an aggressive campaign, to drive the enemy before him and follow up along the two main ways of ingress to the interior. Troops were at once dispatched down the railway to penetrate as far as the city of Vologda four hundred miles to the south, and other troops were sent by tug and barge up the Dvina River, with Kotlas, three hundred miles southeast, as their immediate objective. From Kotlas, there is a branch railway leading two hundred fifty miles further south to the Trans-Siberian at Viatka.

When their missions were accomplished, the Railway Force at Vologda would be nearly due east of the Dvina Force at Viatka, and distanced four hundred miles across the Trans-Siberian railway.

Beyond this stage, the Allied plan was somewhat hazy. It contemplated rather vagrantly a fusion with the Czecho-slovaks along the Siberian railway, after penetration south to this trunk line.

A volunteer brigade of these adventurous soldiers who had been Austro-Hungarian prisoners, but whose whole-souled sympathy was with the Allies, organized in their native Bohemia and Moravia, and joined General Broussiloff in the spring of 1917 to take part in the victory of Zborow near Lemberg. Moving to the railway between Kiev and Poltava in the Ukraine, the brigade recruited more Czech prisoners in Russia until it had grown to the strength of two divisions.

After the peace of Brest-Litovsk, this army corps pushed forward to the middle Volga in the direction of Kazan and Samara intending to reach Vladivostok and sail from there to join the Allied Command in France.

The Soviet authorities promised them safe convoy over the Siberian railway, but instead, treacherously attacked at Irkutsk in Siberia on 26th May, 1918, and the Czechs then divided into two groups, one determined to fight through to Vladivostok, the other under General Gaida bent upon joining the Allied invasion from Archangel.

Although this last aim was not realized (and would have profited little if it had been) the Czechs performed a service of inestimable consequence to the Allies by acting in conjunction with the Anti-Bolshevik Siberian troops, and with the small Allied Eastern Expedition of Great Britain, Japan and the United States, in holding the Trans-Siberian open from Omsk to the coast, so preventing the transportation of many thousands of German prisoners back to Germany. When the Archangel fiasco was brought to a close they withdrew to their own country in October, 1919. And, reviewing the whole unproductive Russian effort in retrospect, the Czechs came closest towards a realization of the mythical "Eastern Front," for, while they could not engage in aggressive action, they did much by negative methods, denying Germany great numbers of returning soldiers that might have been welded into a considerable effective combat force for the Western theatres of war had they been free to enter their country from the Eastern frontier.

The hopelessness of a junction between the Archangel Expedition and the Czechs became certain at the beginning of the northern campaign, and General Poole was advised by the British War Intelligence that Gaida had been driven back in Samara five hundred miles from Viatka and could advance no farther before the commencement of winter.

Still the optimistic Allied Staff clung tenaciously to the belief that all the Anti-Bolshevik Russians could be joined, the Czechs, the Cossacks that General Denekin had organized between the northern Caucasus and the sea of Azov, and a group of loyal officers of the Imperial Army with General Korniloff along the Don. It was within the Allied range of possibilities that all these scattered groups might join the British, French and Americans on the Siberian railway, and after the Staff was thoroughly committed to an offensive campaign, there arose the hope of cooperation from the friendly Russian forces in Siberia. On 18th September, 1918, at Ufa, there was a meeting of representatives from the Governments of Archangel, Eastern and Western Siberia, Samara and Vologda, which purported to form a Central government of all Russia, and to restore the Constituent Assembly.

On 25th October, this group moved to Omsk, created Admiral Kolchak Military Dictator 18th November, and proposed to raise a strong armed force to purge Russia of Bolshevism for all time.

The Allied governments were quick to recognize this Omsk group as the de facto government of Russia.