Why had five spaceships, each tested again

and again right down to its tiniest rivet,

started for the Moon and ended up in Hell?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories November 1951.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

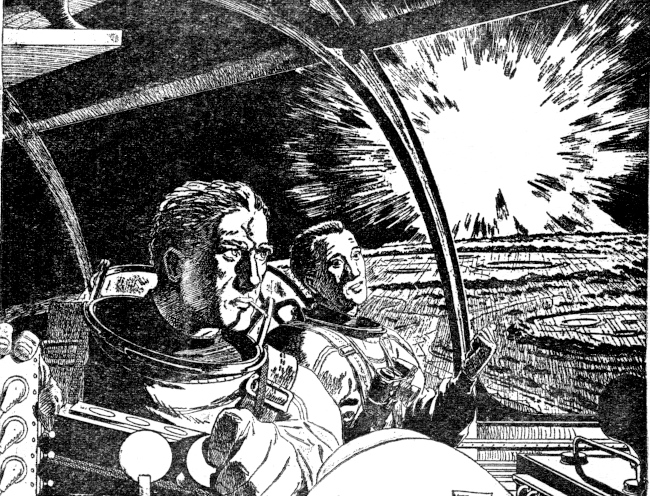

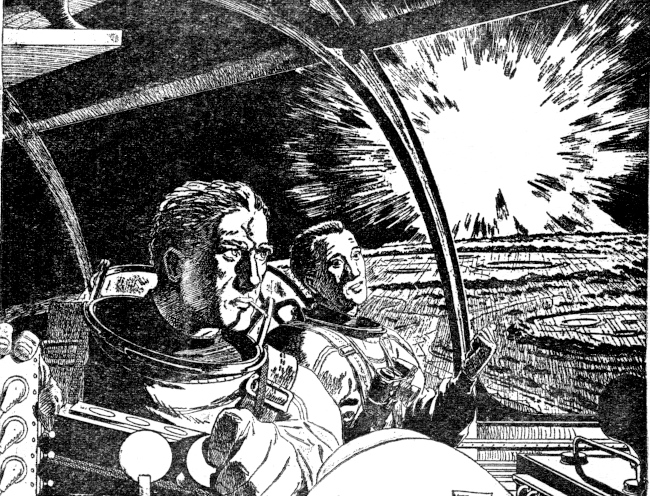

I lit the last cigarette I would ever smoke and took my airsuit out of the compartment under the control-board. The two-man cubicle was coffin-cold even under the blast of sunlight pouring through the forward port, and the air smelled of stale tobacco and machine oil. Beside me Charlie Kosta's voice droned into the communicator, winging back two-hundred thirty thousand miles to the listening millions of Earth.

"Our air is nearly gone," Charlie said. "We have about twelve minutes left for deceleration, but we'll never make landing. The Luna V is riddled like a sieve, spewing out heavy-water fuel along with her air ... it's a miracle that a chunk hasn't crashed through our fuel pile or the communicator—or through us. That's what blew up the first four ships, we know now ... if men ever reach the moon they'll first have to develop some sort of armor that will turn this barrage of meteoric dust."

I got my feet into the plastoid suit and pulled it on, letting the transparent headpiece dangle over one shoulder like a parka hood. Charlie watched me with his tight grin, waiting through the three-second lag of time for Earth's answer. Some high-ranking general down there had pushed aside the Moon Foundation scientists to make himself heard; his voice came over the hiss of static with a tinny, frantic ring.

"Meteoric dust couldn't possibly pierce that alloy hull! It was tested over and over—"

We waited him out, knowing that his frenzy was not for us nor for the success of space flight. He was concerned, like all the military, only with the establishing of a moon base to overlook Earth, an all-commanding launching site that would control a world. Once that base was established, the ferment of war would come to a bitter end; one nation would own the planet.

"But you didn't test the hull out here," Charlie said patiently when the general had finished. "You can't imagine the speed of these particles. We've no protecting atmosphere to vaporize them, as Earth has, and they streak through the ship so fast that they seem to strike both sides of the hull at once.... I'm cutting you over to Leonard Nugent now. Ready, Len?"

It was what I was waiting for. I had looked forward to this moment every day of the nine years I had spent being groomed for the flight, and for half a lifetime of drilling before that. The waiting was almost over.

"I'm ready," I said, and took the microphone. "But there's not much point in reporting further, is there? With her fuel leaks the Luna V will go like an A-bomb the instant we try to use the landing jets, just as the first four Lunas did ... the air is getting thinner, so thin that I'll have to put on my pressure suit soon. Are there any questions?"

My only answer was the grind and roar of static.

I could guess why; they were bickering and quarrelling among themselves down there, the military men snarling at the scientists and the scientists snarling back, each blaming the other for this new failure. The loss of the first four ships had been a mystery until they sent the Luna V out with co-pilots, equipped for full two-way communication. Charlie and I had reported from the beginning of the flight in alternate thirty-minute relays, keeping the Foundation posted so that if anything threatened us they would know the nature of the danger. Now they were getting what they had asked for, and the problem would keep them busy for another ten or fifteen years while the conquest of space marked time. But they couldn't accept even temporary defeat calmly, of course—they had to quarrel among themselves, just as men have quarrelled since they first climbed down out of their trees and set about organizing the business of killing each other.

"We're going to try for a landing anyway," I said into the microphone. "We're going to cut in the decelerator jets as soon as we pass out of the sun glare and into the moon's penumbra, where we can see."

We flashed suddenly into darkness, lost instantly in the vast conical shadow of the moon. The night half of the pocked globe loomed below, faint and ghostly in the blue Earthshine, craggy and desolate, cold as space and as old as time. Earth hung above and behind us, and I couldn't help thinking of the astronomers who had followed our flight patiently every inch of the way. They couldn't see us now; the daylight crescent of the moon lay between the Luna V and the sun, burying us deep in the utter darkness of space.

Charlie took the microphone, speaking this time not to the Foundation but to the millions who sat gaping at their radios. Some of them would be muttering maudlin prayers for our safety, some would be gleefully collecting the bets they had made on our chances of getting across; all of them would be thrilled to the core by the vicarious imminence of danger and death.

"We don't want mourning and demonstrations," Charlie said. "If you people listening to me would like to honor our memory and the memory of the men lost before us, then forget space travel for a while and try to work out a lasting peace down there on Earth. Because it's inevitable that you'll conquer space some day, and if you aren't ready for it when it comes—"

He clicked off the communicator, and we turned to the port together to watch the little metal sphere that hurtled up out of the darkness past the Luna V. From behind and above us there came a great white flash of atomic fire that must have blinded for the moment every watching eye on Earth.

"Right on schedule," Charlie said, and swung the Luna V over the darkside rim and across the mysterious other side of the moon, the hidden hemisphere that no man has ever seen.

The ship was waiting for us there, a sleek, familiar cylinder with airlock standing open.

We went inside and closed the lock and stripped off our cumbersome airsuits, and Charlie flexed his arms and grinned at me. "Lord, I'm glad to get that over with—it's been like nine years of prison!"

"It was worth it," I said. I was remembering the grim green world we had left, shivering a little when I considered the brawling simian hordes who battered their way up the scale toward a culture that might, unchecked, some day rule the Universe.

"It gives us a few more years before they come swarming down on us with their atomic bombs and politics and their gaping tourists," I said, still using the speech patterns that had been drilled into me for half my life. "We've marked time long enough, hoping for the best. We'll need every minute we've gained to get ready for them."

We went forward then to watch the purple-skinned pilot, hairy and many-limbed and beautifully wrinkled, engage the magnetic drive that would send us flashing toward the planet that was home. Later, in our natural bodies, we would speak the name of that world with reverence, but our clumsy synthetic Earth-tongues could not master its lovely sonic extensions, and so we used another term.

For the time being, we called it Mars....