Oregon Society

Daughters of the American Revolution

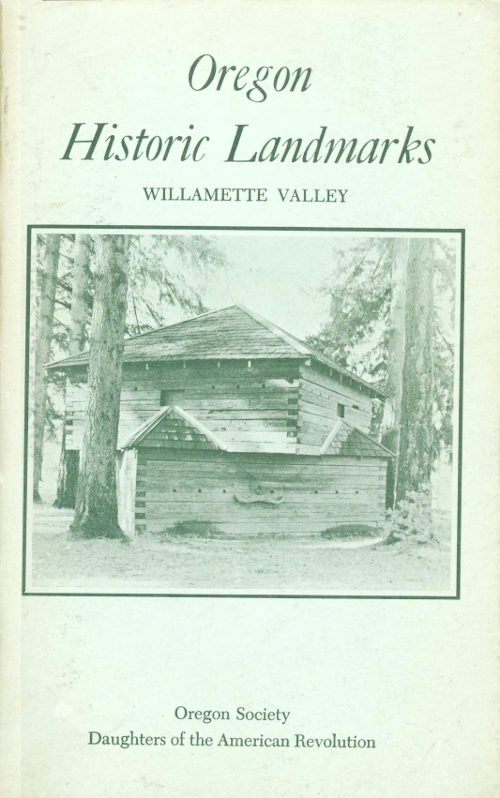

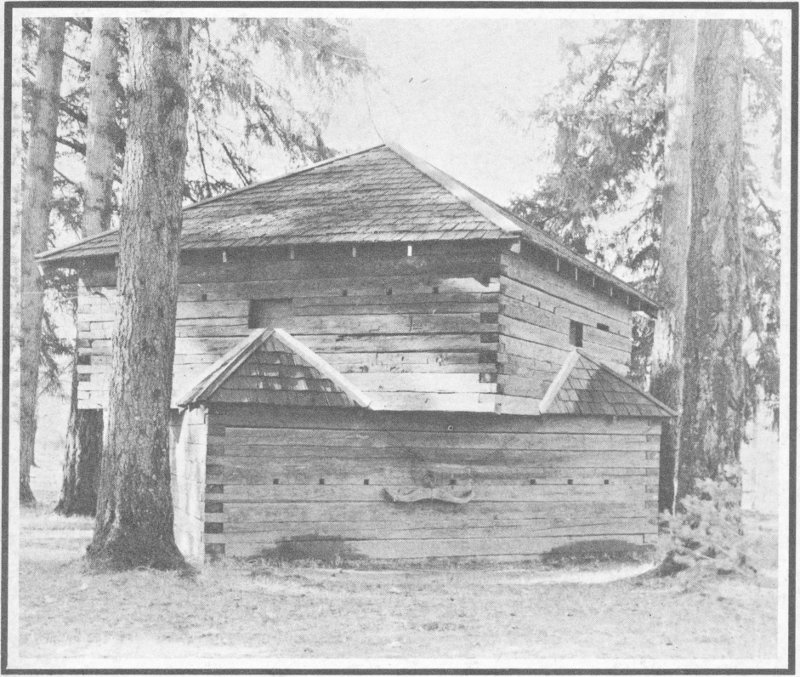

The Blockhouse at Dayton, Oregon

This building was a military blockhouse built at the Grand Ronde Indian Agency by Willamette Valley settlers in 1856. U. S. Troops were sent to the station the same year and it was named “Fort Yamhill.” Among the famous Army officers stationed at this fort were Phil Sheridan, Joseph Wheeler, A. J. Smith, D. A. Russell, and W. B. Hazen.

By permission of the U. S. Government, Fort Yamhill was moved from Grand Ronde Agency to Dayton in 1911, through efforts of John G. Lewis, a patriotic citizen. The structure was rebuilt on this spot as a memorial to General Joel Palmer, a pioneer of Oregon, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, founder of Dayton, and donor of this park.

LANDMARKS COMMITTEE

1963

The State Society Daughters of the American Revolution assumes no responsibility for statements of contributors

Copyright 1963

by the Oregon Society

Daughters of the American Revolution

Printed in the United States of America

by the Metropolitan Printing Company

Portland, Oregon

Oregon’s first sheriff and marshal, Colonel Joseph LaFayette Meek, should be remembered, not so much as a witty adventurer, a part much overplayed by writers, but as one of the very most important—at times the most important—political leaders in this northwest society. True, distance and lack of formal education limited his contribution, especially to national developments. The fact that his mother was a member of the important Walker family, that his uncle Joseph married Jane Buchanan and that his cousin Sarah Childress married James K. Polk might otherwise have opened doors leading to distinction for a man of great natural ability and winning personality.

There were twelve, or by one account, fifteen children in Meek’s Virginia family, too many for one man to educate in a day when schooling was neither universal nor free. Joseph L. Meek chose to go west. From his brother Hiram’s home at Lexington, Missouri, he enlisted in the fur trade in 1829 and continued that wild career for eleven years. Decline of the fur trade forced him to move to Oregon in 1840, driving one of the first wagons ever to reach the present Oregon-Washington area.

The record summarized in the most definitive Meek biography, No Man Like Joe, reveals not only a man with important ancestral ties which he proudly and affectionately maintained, but the fond, doting parent which he always was. Unlike many less responsible trappers, he did not unfeelingly desert his Indian wife and his children, but he took them along with him into the far west.

Adjustment to family life in Oregon was somewhat difficult for mountain people. It was 1842 before Joe had a field of wheat of his own. Besides, his heavy involvement in public affairs interfered with successful farming. Nevertheless, as shown by a letter written to brother Hiram and republished so widely as to reach London, he was a prosperous farmer by 1845. His north Tualatin plains estate, consisting of 642.7 acres of combined prairie and timber land of excellent quality, later became Donation Land Claim no. 61, notification 122, Twp. 1 north, range 2 west. Here, in the autumn of 1845, Joe hauled lumber from Oregon City by ox team and built the first frame house in Twality County. The old log cabin was made available to Uncle Ben Cornelius, his wife and nine children.

The boards used in the new house were probably one by twelves, sixteen feet long, either set upright to form what was known as a box house, or nailed lengthwise on a frame of hewn logs and poles and covered by a shingled roof. This unpainted building was large enough for a house-warming dance, but very inadequate according to present standards. It was a one-story affair, with an attic, no doubt, that could accommodate one or more sleepers. The effective size of the front room was reduced by storage of saddles, pumpkins, apples, and other produce. Thus, although the long kitchen was adequate, the large and maturing family had little more than one-room sleeping quarters. Used to better conditions in the east, daughter Olive, after her return in the fall of 1862, promoted improvements. Unbelievably, there was room for over-winter visits of relatives.

The successive family houses on the original site no longer stand, and the 1866 barn has been torn down. Fortunately, the home of Mrs. Emma Ross Deardorff, in which she has lived since 1872, still exhibits what are close similarities to the dwelling in which Colonel Meek lived during his last years. Living on the original residential site, now the Ernest Zurcher farm, are Mrs. Zurcher (Marjorie Meek), her husband, and the grandchildren of Stephen A. D. Meek—the great grandchildren of Joseph L. Meek.

There was a “lost generation” of Meeks. The Civil War and racial discrimination in the years that followed were principally responsible for the fact that marriages of all surviving Meek children were delayed until later in life than is normal. The grandchildren of Joseph L. Meek, who are now at the peak of their careers as average, respected, useful citizens. Best known in Oregon is druggist J. Fred Meek who is now, after another reelection, serving as representative in the state legislature.

Oregon Historical Society

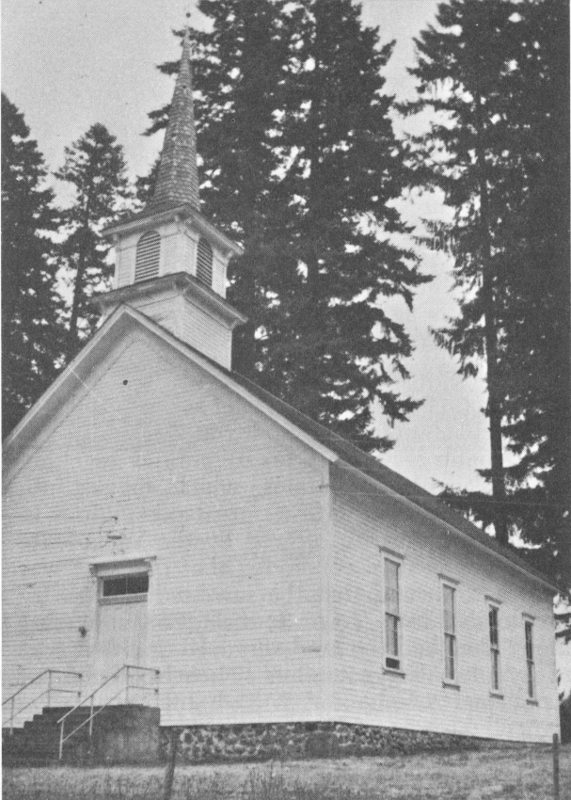

“We the undersigned agree to pay the sum annexed to our names severally for the purpose of Erecting a house of worship; to be the property of the West Union Baptist Church of Jesus Christ our Lord and Saviour; said house to be built in Washington County O. T., upon a lot of land furnished by David T. Lenox which the said Lenox and wife secures to the church by lease as long as they shall use it for a house of Worship, together with a burying ground, the lot of land is on the east side of the Lenox land claim at a point of timber adjoining the prairie, the house to be of good style frame 30 foot by 40 foot Square finished in good Style, the payments to be made to the trustees, David T. Lenox, Henry Sewell and Reubin W. Ford.”

* * * * * * * *

Thus reads a subscription paper dated April 20, 1853, which records pledges of $749.70 toward the total cost of $1,512.43 of the West Union Baptist Church. The average gift was $5.00 but David T. Lenox heads the list with $200.00, his son, Edward, $60.00. Generous pioneers of other faiths made contributions, including Dr. John McLoughlin, D. H. Lounsdale, and James Failing.

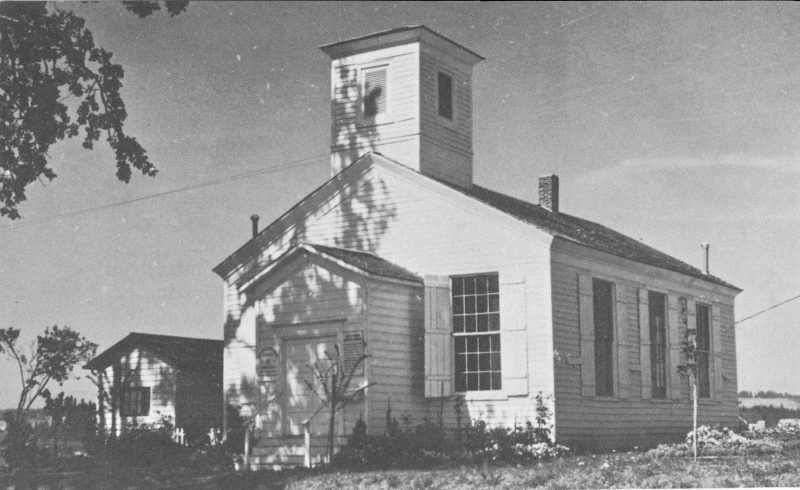

On May 25, 1844, five Baptists met in the log house of David Lenox on Tualatin Plains, about eight miles northwest of Hillsboro, and constituted the first church of the Baptist denomination in Oregon. 7 Their Minute Book shows that they named their church the West Union Baptist Church, decided to meet once each month at the homes of members, and elected David T. Lenox temporary Moderator. Subsequent entries clearly show that Lenox was the leading member of this pioneer church.

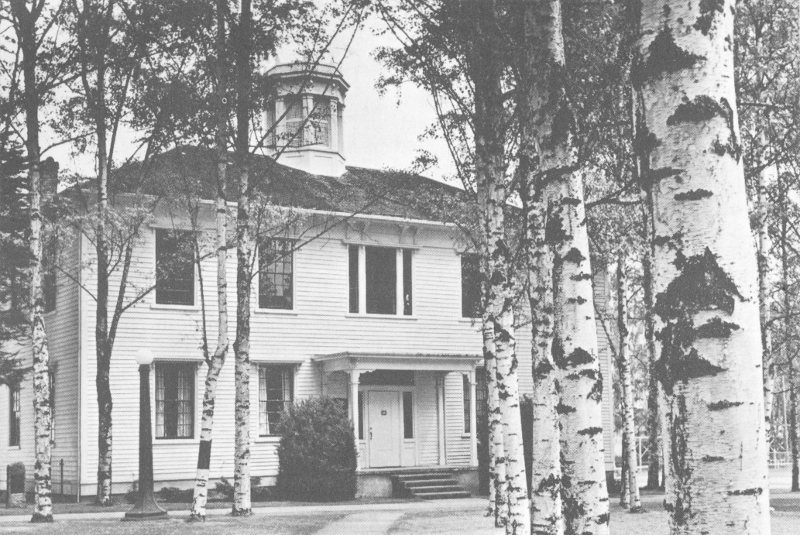

He was born in New York State in 1801, lived in Illinois and Missouri before leading a company of the 1843 wagon train to Oregon. Lenox sent out the call in 1848 that resulted in the formation of the Willamette Baptist Association. Although he was elected Moderator and Deacon, Lenox was voted out of his church in November, 1862, but was reunited with it before his death in 1872. His grave may be seen in the burying ground adjoining the white, turreted church situated on his Donation Land Claim. The West Union Baptist Church is the oldest Baptist Church west of the Rocky Mountains and one of the oldest Protestant buildings still standing in Oregon.

The Minute Book records the appointment of three committees to locate a site for a Meeting House, but it was not until David Lenox offered a portion of his land on April 9, 1855, that any progress was made toward the erection of the church. The Reverend Ezra Fisher, who was sent to Oregon by the American Baptist Home Mission Board in 1845, delivered the sermon of dedication on Christmas Day, 1853.

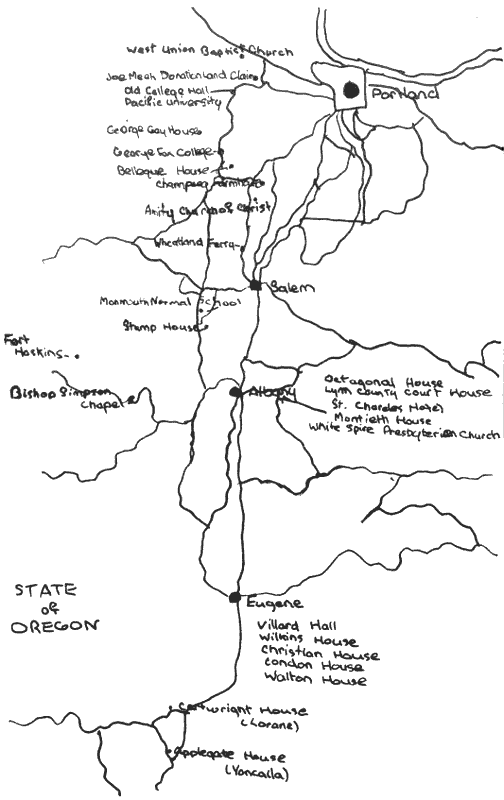

The West Union Baptist Church is the only pioneer church in Oregon, measured, blueprinted, and photographed in the Historic American Buildings survey in 1934. This project was carried out by the Civil Works Administration in cooperation with the National Parks Service of Plans and Designs within the Department of the Interior throughout the United States. It was a depression measure that offered employment to architects and secured records of great value pertinent to early American architecture.

Thirty-nine districts for research were designated. Oregon and Washington were “District 39.” The Oregon members of this district committee were Walter Church, architect, Portland; Nellie B. Pipes, librarian of the Oregon Historical Society, and W. R. B. Wilcox, Dean of the Department of Architecture of the University of Oregon. They employed twenty architects and two photographers. On the closing date of the project, April 28, 1934, forty-seven structures in Oregon and seven in Washington had been studied, delineated and photographed.

A list of these buildings may be found in the Oregon Historical Quarterly for June, 1934. Photographs and facsimiles of the blueprints may be inspected at the Oregon Historical Society Library in Portland or purchased through the National Archives in Washington, D. C.

According to the caption on the bronze marker placed by the Multnomah Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution on May 12, 1939, “College Hall (is) the oldest building in continuous use for Educational purposes west of the Rocky Mountains. Here were educated men and women who have won recognition throughout the world in all the learned profession.”

In this building Tualatin Academy developed into what is now Pacific University. When the Academy was chartered in 1849, the classes met in the log cabin erected for the Congregational Church in West Tualatin Plains, now Forest Grove. But in 1850 the board of trustees authorized the erection of a two-story frame building. Here are the words of one of the students, Marcus W. Walker, concerning the “raising”:

“It was in 1850 but in the early summer and never did a brighter sun shine through, a bluer sky or more brilliant green bedeck forest and grove and plain than did those in which boys reveled during those days in which the frame of the old Academy building was placed in position.

“All spring, men and teams had been hewing out and hauling timbers while other men under the oversight of ‘Squire Tuttle,’ as he was familiarly called, had been framing them and now they were ready to be put together. It was yet in the days of log houses and ‘bee-raisings’ and notices and invitations had been sent out naming the day when everything would be ready. Men with families came from other neighborhoods in white-covered ox wagons, camping out for the time, and the affair greatly resembled the old-fashioned camp meeting. Tables were set in the old log building, partly school house, partly church, which has passed into history as the birthplace of Tualatin Academy and Pacific University, where bountiful dinners were provided by the women for the men at work. This department being under the energetic oversight of ‘Grandma Brown’ with her somewhat stern face and dignified bearing, but we knew that behind them lay the kindest heart that ever befriended a homeless orphan whose name is, if possible, more intimately associated with the history of this institution than that of Rev. Harvey Clark, its founder and patron.

“Squire Tuttle gave the signal, ‘He-oh-heave’ and up it went and settled into place. Money was scarce in those days and houses were built in a hurry so a winter and a summer passed away before even one room was ready. It was a frosty morning in October 1851 when 25 or 30 of us gathered in the lower north room and school began with J. M. Keeler on the platform. The fresh ceiling on the walls and overhead, the large new blackboard, the new double desks, homemade as they were, all combined to make it a veritable palace, used as we were to the rough log walls of the old building with its rough benches and long shelf running around the sides for desks.”

The building cost about $7,000 and the trustees were $2,000 in debt. The Rev. Harvey Clark gave 200 acres of land at first; this plot of ground was divided into lots and many of them were sold to help pay for the building. Later he gave more land for the same purpose. Tabitha Brown mentions in a letter that she gave $100, a big sum in those days, especially for a woman of 69 or 70 years of age earning her own money. Mrs. Mary Walker, wife of Rev. Elkanah Walker, gave her watch which was sold and the sale price added. Others gave generously also and the Society for the Promotion of College and Theological Education in the East contributed to the upkeep of the Academy.

In 1854, the Territorial Legislature granted a new charter with full collegiate privileges to “Tualatin Academy and Pacific University.”

The impressive home of General Joel Palmer, with its stately columns, catches the eye and excites the curiosity. In Dayton’s City Park one of the few authentic blockhouses remaining, compels attention, and each year thousands of tourists read that it stands as a memorial to General Palmer; out of the dusty past ride the well-known figures of Sheridan, Grant, Russell (who died at the Battle of Winchester), Wheeler, (both of the Confederacy in the War between the States and of the Union in the Spanish-American War), all identified with the historic blockhouse. But no note is made of the regal structure which views the passing parade from its vantage point of the State Highway which traverses the small town; and history has itself passed by one of the most colorful persons who helped hammer out the destiny of Oregon.

Let us look first for a moment to this man—a man who shaped the future, first of the Indians who occupied the land, and then of his fellow countrymen. As Superintendent of Indian Affairs, he negotiated the treaties whereby the red man ceded title to the Oregon Country; these were ratified by the United States Senate and became the law of the land. Because of his humanitarian attitude toward the Indians, Palmer was the victim of unfair criticism. But when the Whitman massacre resulted in the Cayuse Indian War, Palmer readily took the field against the errant, and it was in this War that his title of “General” was obtained. Yet all the while, he served his fellow countrymen in numerous ways. In Indiana he had 11 been a member of the legislature before his first trip to Oregon in 1845.

As Faith Holdredge Watts says, he was then “on a journey of exploration, to test the feasibility of taking his family out later and establishing a permanent home there.” He was immediately elected captain of one company and in the fall of that year with Sam Barlow established what is now known as the “Barlow Trail”—a portent perhaps of how perverse history would refuse to recognize this leader, and give its laurels to another. Palmer then platted the Town of Dayton in 1850, setting aside the City Park as a “Court House Square” and the Brookside Cemetery in which he was later buried. His picture, in the Oregon State Capitol, looks down upon each Speaker of the Oregon Legislature, for he was the second Speaker of the Assembly—but again, perverse history dismisses him with a reference to a “Joe” Palmer; he was a State Senator, refused to run as a candidate for the United States Senate while in government employment, but in 1870, was the candidate of the burgeoning Republican Party for Governor, being defeated by less than 700 votes. He was characterized as a “man of honesty and integrity.” This was the man who built the house.

The house itself has been rebuilt, added to, and a part destroyed. Gertrude Palmer, granddaughter of the General, lives today in Lafayette, Oregon, and her mind leaps quickly back to the olden days; she recalls as a small child holding her grandmother’s hand while the original structure (one story and attic, with a double fireplace) was demolished. In the 1860’s, Palmer built an additional part which was remodeled in 1911, giving the present structure a “southern plantation” look. Palmer’s original Dayton home was Dutch Colonial. He was a “bound boy” in his youth; with no formal education, he struggled to achieve the recognition he received. The house would reflect his personality.

To this home, says his granddaughter, came orphans—and one sees here his hope that they be spared the rigors of his own youth. One of these, Christopher Taylor, drove the wagon train that brought Palmer’s wife to Oregon. Christopher Taylor was from Dayton, Ohio; and so the Oregon counterpart came to be named.

Palmer, although a distinguished leader in the pioneer community of Oregon, was apparently not fully aware of Oregon’s rainfall when he built his home. To the Civil-war period portion of his house (and incidentally, as a Republican leader he was strongly pro-Union), he dug a deep-bricked cellar, which filled with water during the winter months. Gertrude Palmer reminisces that when it so filled, “We used to get our shingle boats and play in the cellar.” This pastime became denied to juveniles with the 1911 remodelling.

Ten years after William Hobson settled near the site of Newberg in 1875, the Friends had opened an academy for their children, the first Quaker school in Oregon and the forerunner of Pacific College, now George Fox.

In 1883 the pioneer Quaker parents, feeling the need of education for their children beyond that offered in the Oregon public schools, brought the subject of building an academy before the Monthly Meeting. Mary Edwards, Dr. Elias Jessup, David Wood, and Ezra Woodward were appointed to investigate.

By September, 1883, the committee reported $1,865 secured in good notes and that the subscribers had met and decided to call the school, Friends Pacific Academy.

C. J. Edwards recalled the establishment of the academy vividly. “One evening in the spring of 1884, as I was returning from school, I noticed that someone had cut a wide swath of wheat down along the west side of our garden and that several loads of lumber had been hauled to the place where the Friends Church now stands.... My father said he was very much dissatisfied with having to sell some of the land in the center of his farm for an academy building but that he was so anxious to have the privileges of the school for his family that he had consented to its erection near the center of the 80-acre field on the spot where the Friends Church now stands.”

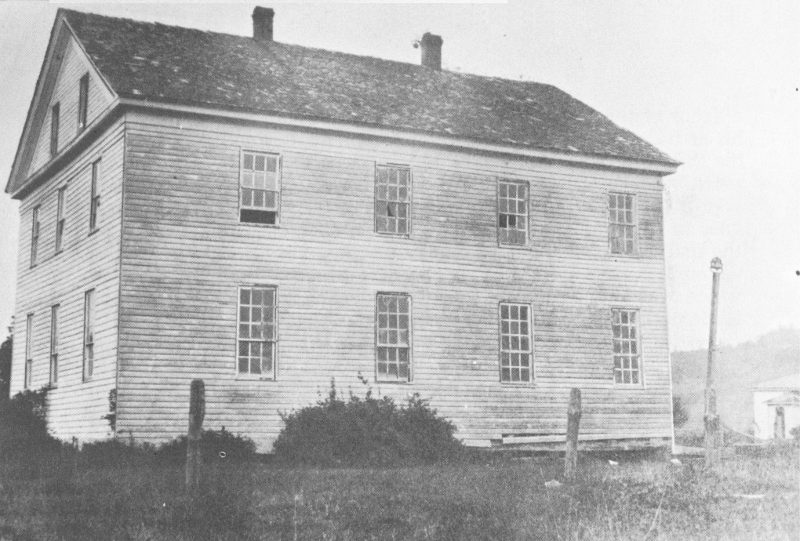

On September 28, 1885, Friends Pacific Academy, a school of high school rank, opened its doors. Dr. Jessup had hauled the first 13 load of lumber with a mule team for the building, and Noah Heater and Charles Vaughn had contracted for the carpenter work.

The first academy building was moved in 1892 to the present campus where it became known as Hoover Hall in 1932 and was used as a men’s dormitory for twenty years. The architects declared it was suffering from “extreme fatigue,” and it was torn down in 1954, destroying a wall on which tradition says Herbert Hoover signed his name “Bertie.” The senior rose garden marks the site of the historic academy building.

Among the first to enroll on opening day was Bert Hoover, later thirty-first president of the United States. Then eleven years old, he was living with his uncle, Dr. Henry Minthorn, Pacific’s principal. On the college’s fiftieth anniversary Mr. Hoover was granted Pacific’s first honorary degree and his fiftieth.

When the academy opened, there were two of senior rank, eleven in the first year, twelve in the second, and thirty-four in the first year of the grammar department. There were two teachers besides Dr. Minthorn.

Six years later there were 125 students attending classes, and one had graduated. The Quakers were now confronted with the problem of providing further education for their children, and, since the nearest Quaker college was in Iowa, they decided to start their own.

Pacific College opened its doors on September 9, 1891, with Dr. Thomas Newlin as president. There were six other instructors. The college’s aim was that of “offering to young men and women the benefits of a liberal Christian education.” Two juniors, four sophomores, and seven deficient in preparatory work were enrolled in the college; and 136, in the academy.

Pacific’s first graduates were Clarence J. Edwards, son of Jessee Edwards, in whose wheatfield the academy had been built; and Amon C. Stanbrough, an early superintendent of Newberg schools.

In 1949-50, final action was taken to change the name of Pacific College to George Fox. It was felt that the increasing confusion of Pacific College with Pacific University at Forest Grove and the use of Pacific in the names of other schools on the Pacific coast made such a change imperative.

There are few colleges that send a larger proportion of their graduates into the so-called sacrificial fields, as teachers, preachers, or missionaries. George Fox, the fifth oldest Quaker college in the United States, emphasizes constantly the ideal of service rather than selfishness, and of character as well as scholarship.

George W. Eberhard, at the age of 22, arrived at San Francisco by way of Panama from the State of Michigan. He remained in California for five years and came to Oregon by boat in 1859. The following year he bought 320 acres of the Pierre Belleque farm above Champoeg. At that time only 60 acres were cleared. He paid $1,500 for this land which had been farmed by the Belleque family over 25 years. Because of technical regulations in the Land Grant laws, no clear title had been issued, and it was 28 years before Mr. Eberhard was able to secure his official title.

This farm belongs to the very earliest period of Oregon history, having been the location of one of the first fur-trading posts in the entire Northwest Country. It was established by members of the Astor expedition in 1812, and when the Hudson’s Bay Company came to this Western Empire a decade later, they took charge and maintained it as a supply depot and relay farm for brigades going to the Umpqua and country to the south.

It is in the big bend of the Willamette River in Marion County, located two miles west of Champoeg on the river road to Newberg. Highway 219 to the new bridge is the west boundary of the original farm. A historical marker has been erected near the bridge.

Pierre Belleque, who came with the Northwest Fur Company from Canada, settled here in 1831 to develop a farm and home and raise a family, along with other retired fur company men. His neighbor to the west was Etienne Lucier. Here they became prominent in the early history and development of the Northwest Country, long before the wagon trains began to roll over the Oregon trail.

It was the house of Belleque which had been the chief trader’s house, built in the French style, having lapped siding; and dressed lumber was used for finishing. The house had been lined with flowered glazed chintz, a piece of which is still preserved. An outstanding feature was the glass in French-style windows, while the usual log cabins with parchment windows and rough lumber comprised the homes of his neighbors.

Mr. Eberhard, a bachelor, was living here when the flood of 1861 destroyed so many homes and towns along the Willamette. He saved it from going down to destruction in the swirling waters and anchored it on a higher bench of land. Here he brought his bride, Louisa J. Jones in 1865. Soon he began hewing the timbers and building their new home, moving into it in 1869. They used the handmade mantel from the chief trader’s house, and many of the doors and windows. To them were born six children—five boys and a girl, Barbara, who married Henry J. Austin, one of the early merchants of Newberg. They had two children—Louise Austin of the Friendsview Manor in Newberg and George Kenneth, who with his wife still lives in this house in its park-like setting of stately old black walnut and hickory trees. This grandson was among the first to develop an extensive irrigation project. Today he operates a modern dairy.

Although the house has been remodeled, much of the original handwork can be seen. The broadaxe used to fashion the beams still stands by the fireplace. The original hand-dressed flooring remains in one room nailed with handwrought iron nails. One of the original shingles, hand-split and gently tapered with plane or draw-knife, is preserved.

The family has collected shards of china, pottery, old pipe stems and bowls, and various relics from the site of the old trading post, which portion of the farm was sold many years ago.

To this farm belongs the honor of having reared enterprising citizens from the time Pierre Belleque was appointed as one of the first constables—before the formation of our provisional government—to the present day, when the son of Mr. and Mrs. G. K. Austin aided in the designing of portions of our modern-day missiles.

The house on Champoeg Farm was built between 1867-70, by John Hoefer and Casper Zorn. It is a combination of southern and western design, a two-story frame building, consisting of fourteen rooms. The structure has a brick pillar foundation and the pillars are covered with zinc sheeting, to protect the sills from moisture. The fir lumber used in the building was produced on the farm and wrought-iron square nails were used in the construction. In the front part of the house the lumber was planed, tongue and groove, by hand.

This building was enlarged in the 1880’s to its present size. In 1896, a bell tower, on the roof at the rear of the house, was added. The bell was to call the farm hands from the field at the noon hour. In the same year, the windmill tower was built.

The house was completely furnished; carpeting with large floral designs, heavy drapes, and such furniture as was in use at that period, along with many pioneer articles.

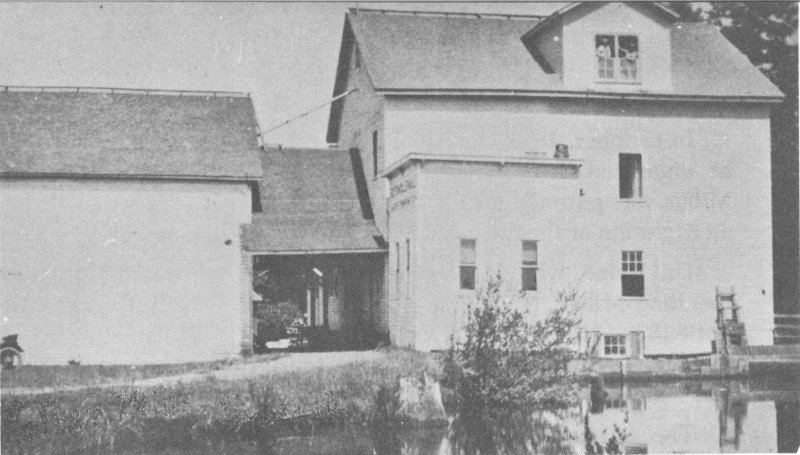

The house is in the center of the Robert Newell Donation Land Claim, surrounded by about 950 acres of fertile farm and timber land. The name Champoeg Farm was registered June 9, 1913, in the Marion County Clerk’s office, Salem, Oregon. The reason for naming the farm was to give it an identity. The largest Indian village 17 in the Willamette Valley was located here. The French Prairie was known as Champoeg Country. Champoeg District, which extended from the Willamette River to the summit of the Rocky Mountains, was named by the Provisional Government. The first flour mill of 1835, and all succeeding mills were known as the Champoeg mills. The establishment of the first American government on the Pacific Coast occurred here. The townsite of Champoeg was situated on the northwest section of the farm.

There were a number of individuals who had a part in the development of the farm by ownership or otherwise, who made history by their courage and determination and who became useful members of a new state. I am mentioning the names of the most prominent: Robert Newell, Donald Manson, William Bailey, Thomas McKay, William Cannon, John Ball, William Johnson, George Laroque, John Hoefer and Casper Zorn. Personally I have owned the farm over fifty-two years.

John Hoefer sailed from Europe to New Orleans; the voyage took six weeks before arriving. For two years he worked as a cabinet maker and then he came by wagon train to California and thence to Oregon by steamer, coming to the Champoeg district in 1852. After arrival, he worked as a cabinet maker and carpenter, building houses for the settlers.

John Zorn, his two sons, and daughter came from Europe to New York and then to Baraboo, Wisconsin; and after a time, decided the Pacific Northwest was the place to establish their home. They went down the Mississippi River by boat to New Orleans, then by steamer to Panama, across the Isthmus, and then by steamer to California, and from there by steamer to the Oregon country, settling in the Champoeg district in 1854.

John Hoefer married Anne, the daughter of John Zorn. Casper Zorn, the older of the two sons, became a partner of John Hoefer. Adam, being a boy, chored around until he became old enough to go on his own.

Hoefer and Zorn ran the old tavern, where the Hudson’s Bay Company quarters had been. They also had a bowling alley, at the townsite of Champoeg. All their property was lost during the flood of 1861.

On February 3, 1862, Hoefer and Zorn bought the flour and gristmill, which had been damaged by recent flood, repaired it, and operated it for fourteen and one-half years. Then on February 24, 1866, they purchased 146 acres from Robert Newell, and the Champoeg Farm house was built on the present site.

In the late fall of 1834, under heavy rains, Jason Lee and his few co-laborers built the log cabin which was to house the Oregon Indian Mission of the Methodist Church. The crudely built cabin of twenty-by-thirty feet was on the banks of the Willamette River, about ten miles below the present city of Salem. As the mission became an Indian orphanage and school, and its mission workers and their families increased in numbers, the log cabin received additions; and a small colony of cabins serving as homes, utility buildings, and work shops grew. These buildings were swept away by the flood of 1861, almost twenty years after the mission activities had been transferred to the present site of Salem.

Only one building of the old mission structures survived the flood. This was the first frame structure, built in 1838, to house the mission doctor, Elijah White; and later added to, so it could serve as the mission hospital. The site selected for the first frame structure was on higher ground, about a mile east of the mission log buildings on the river bank. The location today is on the Wheatland Ferry Road, about ten miles from Salem, on what is now (1963) known as the Mission Blueberry Farm. Oregon’s oldest frame house is privately owned and occupied, as it has been during most of its century and a quarter of history. When the Old Hospital was first known to the writer, about 1920, it was called the Beers’ house because of its long ownership by the Alanson Beers family. This mission family had originally acquired it from the Oregon Mission, when it closed its Indian Mission in 1844. At the time I first visited the house it was unoccupied and showed considerable 19 neglect. In the years since, it has passed through a succession of owners, most of whom have appreciated its historic significance and kept it in fine repair.

With the arrival of the first reinforcement of mission workers, including the first physician, Dr. White, in 1837, and others in 1838, the living conditions in the old mission quarters were impossibly crowded. In a book published in 1848, based on Dr. Elijah White’s source materials, the writer says: “There was some difficulty in accommodating the new comers, but they were obliged to enter the house with the old inmates, already numerous.... (This) made Mrs. White anxious to remove to their own house, which they did in a few days although it was not fit condition for inhabitants. There was no chimney in it, and but roof enough to cover a bed; a few loose boards for a floor, and one side entirely unenclosed.”

The house was completed as soon as possible. But as there was no suitable stone at hand for the hearth, it was made of clay and ashes “which after drying, became measurably though not perfectly hardened. But one of Mrs. White’s greatest domestic privations was that she could never wash her hearth.”

When the mission carpenters, under W. H. Willson, finished the house, and Mrs. White was settled, she made it a home which won praise from the wife of the Fort Vancouver chaplain, the Rev. Herbert Beaver, when she and her husband visited the Whites. “They were much pleased with everything around them, especially the indoor arrangements. ‘Why, Mrs. White,’ said Mrs. Beaver ‘how nice this is; it looks as though a white woman’s hands had been here. This is the first white woman’s house I have been in since my arrival in this country.’”

Many visitors besides the Beavers stayed at the White home, including Dr. Marcus Whitman, from the American Board Missions; Dr. McLoughlin, and visiting missionaries from the Hawaiian Islands. From the size of the retinue which accompanied Dr. and Mrs. McLoughlin, and the description of their camping equipment, it must have been that they camped near the house while they visited, as the party could never have been housed under its roof.

We have a description of the Mission Hospital, as it was some years after Dr. White’s occupancy, from Lt. Charles Wilkes, a United States government exploring agent, who visited the Willamette Valley in June 1841. “We rode on to the log houses which the Messrs. Lee built when they first settled here. In the neighborhood are the wheelwright’s and blacksmith’s, together with their workshops, belonging to the mission, and about a mile to the east, the hospital, built by Dr. White, who was formerly attached to the mission.”

Wheatland Ferry crossed the Willamette River at a very historical pioneer spot. Jason Lee chose the location for the first Methodist Mission of the valley, a short distance south of the village of Wheatland on the east side of the river. There were no roads, so traveling was by water or horse-back, and the first river crossings were in Indian canoes, with often a horse swimming behind.

In 1837, David Leslie came to help at the Mission, bringing his wife and three daughters. They lived in a log cabin on the west side of the river and crossed to the Mission. By 1840 two more daughters were born. They were the first white children born in Yamhill County. In 1843, Daniel Matheny crossed the plains and took up a donation land claim reaching the river at Wheatland. His family operated a ferry across the river for many years, beginning in flat bottom skiffs, and later with a flat boat for wagons.

Here is a story of pioneer days. Matheny’s oldest son was told by his mother that he was too big to go to Camp Meeting without shoes, so he would have to stay home. This was a sad situation as Camp Meeting was the social event of the year. An Indian woman came to the river and signaled for him to come over to take her across. When he reached her he saw her moccasins and began to bargain for them. At first she shook her head, and he began to empty his pockets. At last she consented and he ran home waving his moccasins.

The land around Wheatland was settled rapidly in the 1840’s, and as wheat was the main export, a warehouse and boat landing were built a quarter of a mile south of the ferry by Miles Hendrick. 21 Wheat was raised on both sides of the river. There is no high ground on the east side of the Willamette river for buildings or boat landings. The first warehouse was built a mile south of Wheatland on a bluff near the west bank of the Willamette river. It went out in the 1890 flood. The other one was built about a quarter of a mile north of Wheatland. After harvest the ferry was busy bringing wheat from across the river to the warehouse to be shipped on river boats.

I remember the ferry in the late 1890’s. It was a thrill to cross the river on it; but as the charge was twenty-five cents one way and forty cents round trip, we didn’t cross often. As children, my cousin and I used to go down and ride across free when the ferry man was taking a wagon. He never refused us and no child drowned from the ferry at that early day.

After the Matheny family moved away, the ferry was owned by John Isham, Bill Isham, Dick Wood, and Lane Davidson. While Davidson ran it, a new ferry boat was built. In the early 1930’s, Clyde Lafollette bought the ferry and built a cabin on the ferry so that his son, Clarence, could sleep there and be ready to take late travelers across. There were current boards on the ferry that made the river current help push it across. If the current wasn’t strong enough, the operator had to help with his own strength. Later Mr. Lafollette put a gasoline engine on the ferry to help while the river was low in the summer time.

In 1937, the communities on each side of the river, backed by Clyde Lafollette, began pressing for a free ferry supported by the two counties it connected. Yamhill and Marion counties took over the ferry that year, hiring two men to run it and keeping it open from six a.m. until five p.m. They installed a new gasoline ferry and, of course, ferry travel increased.

Tom Bowden, who is still working on the ferry, began operating the gasoline ferry in 1940. Other helpers have been Roy Lafollette, George Frauendeiner, Frank Hersha, and Frank’s son, Erwin Hersha is the second operator at the present time. There have been two drownings near the ferry on the Wheatland side; Jackie Worthington in 1941 and Sonny Lindsey in 1947. Both were in their early teens and could swim a little. In 1947, a new electric ferry was built that could handle six cars at a crossing, and in the summer time it was often kept busy. In 1959, the present ferry was purchased. It is an all-steel electric one and handles six large cars.

The Wheatland Ferry is one of the few remaining on the Willamette River. In crossing it, you get a wonderful view both up and down the Willamette. If you enjoy the romance of a ferry, do come and cross the Beautiful Willamette on the Wheatland Ferry.

Oregon Historical Society

George Kirby Gay was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1796. Gay went to sea at a very early age as a messboy on a voyage to the South Sea Islands and other foreign ports. He left London on the whaler “Kitty.” Landing in New York, he made his way westward to Missouri, where he joined the Pacific Fur Company as camp-tender. Soon he started the overland trek through the wilderness, arriving at Astoria in 1812. The following year, Gay left Astoria and for years sailed the seas to all parts of the world.

After his seafaring life, he left ship at Monterey, California, and joined a trapping expedition, soon starting overland to reach the Willamette Valley and the Columbia River, knowing, however, white men might be found. He was a survivor of the Rogue River Massacre, finally arriving at Wyeth’s Trading Post on Sauvies Island in August, 1835.

The following year, Gay was one of twenty to make the attempt to stock the country with cattle. A goodly number of Spanish cattle were brought through and the Colony benefited by this first business venture. While driving the herd through the Siskiyou Mountains, the company was ambushed. Gay received a fearful wound from an Indian’s arrow. The Spanish cattle brought from California, enabled Gay to build herds that roamed Yamhill and Polk Counties.

Now, being settled somewhat, he thought of a home in the heart 23 of the green Willamette wilderness. He busied himself with the making of brick from the local clay. Clay dug from a nearby pit was “tramped bare-footed,” molded, and burned into brick on the place. With these first Oregon-made red brick, the first brick house west of the “Rockies” was constructed. As a site for the brick house, Gay selected an elevated location, affording a view in all directions. A two-story home with 14-foot walls, built of brick three courses thick was built. At each end of this home was an inside fireplace two feet deep. Hand-dressed woodwork and particularly the woodwork around the fireplaces, handcarved, bore mute evidence of the taste and patience of the one who dreamed of a mansion on a hill. The south wall was designated in Oregon records as a point in the southern boundary of Yamhill County. Here was the scene of unbounded hospitality.

Gay entertained officers of the U. S. Navy and all officers of the British men-of-war, who were visiting in the Columbia. This home was a resort for any and all travelers and immigrants who sought its shelter. He had many servants. During the 1840’s, this house resounded to discussions about Oregon’s provisional government. Meetings were called in March for the purpose of devising means of protection for the herds and to protect the lives of the settlers. At the March 6, 1843 meeting, Gay was chosen one of a committee of 12 to take into consideration the propriety of taking measures for the civil and military protection of the colony. It was this meeting which promoted the epochal meeting at Champoeg of May 2, 1843.

For 40 years, Gay was esteemed by companions as a rollicking good fellow, whose temperament and adventures were becoming to the sailor, fur trapper, valiant Indian fighter, and frontiersman of the early 19th century. He was not a man to be trifled or fooled with, but a useful member in his community—in short, he undertook any and all irregular sort of business, and few things with him were impossible—all had much confidence in him. A handsome, athletic man of powerful physique, he was kind and gentle in his behavior and always good-natured. He was a fine horseman and an expert with the lasso.

For years he was the wealthiest man in the Willamette Valley, outside of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Like many of the old, generous, and hospitable pioneers, he died poor—in his own home—a remarkable career man. The career of the intrepid George Kirby Gay ended, October 7, 1882.

The Amity Church of Christ was born in a pioneer log cabin about two miles north of present-day Amity in March of 1846. This makes it the oldest Christian Church of the Disciples of Christ, west of the Rocky Mountains.

Elder Amos Harvey, a pioneer of 1845, was the organizer of this congregation of thirteen charter members. In a letter to an Eastern religious journal, he tells of the humble beginning of this congregation in these simple words: “We met, as the disciples anciently did, upon the first day of the week, to break the loaf, to implore the assistance of the Heavenly Father, and to encourage each other in the heavenly way.”

Amos Harvey was born of Pennsylvania Quaker stock. The Revolutionary Battle of Brandywine was fought on his kinsman’s land. When a young man, he married Miss Jane Ramage, a member of the Christian Church, and after their marriage he became a member of the same church. He was the organizer of Bethel College in Polk County, chartered in 1856. He had one of the first fruit nurseries in the Oregon Territory and was one of the first officers of the state horticulture society. He was one of the founders of the Republican party in the state.

The second minister of the Amity Church of Christ was Glen O. Burnett, a pioneer of 1846. Soon after his arrival in the Amity area, we find him busy preaching, baptizing, marrying, and burying the 25 citizens of this area. He performed his first marriage, shortly after his arrival in 1846, in the cabin of Joseph Watt, another pioneer of the Amity community. Elder Burnett was a hard-working circuit rider. He was a close friend of Amos Harvey, and the two of them kept the Amity church alive in its infancy. A great amount of credit goes to the laymen of the Amity church of this period. They were the real leaders of the community, and they in turn supported Harvey and Burnett with all that they had to offer in a material way, which was very little. But what they lacked in material help they made up in their faithfulness to this pioneer church.

The congregation met in the homes of the members until 1849, when a log school house was built in the north end of present-day Amity. A young schoolmaster by the name of Ahio S. Watt named it Amity. And we find that Elder Glen O. Burnett “delivered the principal address when the first school in Amity was opened in the spring of 1849.” The California gold rush took some of the members to the goldfields for a few years. The Indian and Civil wars retarded the progress of the little church. It was not until 1869 or 1870 that it had its first building.

The ground for this building was given by Enos Williams, who also gave the village square in front of the church to the children of Amity in perpetuity. The building was erected by a pioneer carpenter, Charles Burch. This building served the congregation until 1912, when the present church building was erected seventy-five feet west of the original structure. The old building was moved to another part of town and is still used for church purposes by another religious communion.

Enos Williams, William Buffum, and Robert Lancefield were charter members of this church. They were leaders in the community, school, and church life of this period. These laymen did not confine their good work to the Amity area alone. When circuit riders Harvey and Burnett founded Bethel College in Polk County, they sent their children to its high school department and college classes, or supported it with financial help. The pioneer Amity Church of Christ is not a story about a wooden building as much as it is a story of great men, both its ministers and its laymen—men who were willing to sacrifice for their faith.

The church at one time was in grave financial difficulty. There was a possibility of losing its building. A member, Heber Martin, then past seventy years of age, went to the bank and offered to mortgage his farm to save the church building from a mortgage foreclosure. Happily, this man’s faith aroused the community and the property was saved.

Oregon Historical Society

In the figures of the 1850 census, there were no illiterate persons in Polk County. This was due to the high quality of the pioneers who settled in this area of present-day Yamhill and Polk Counties, which was called “The Athens of the West.” Between the years of 1843 and 1860 some of the best educated and most dedicated men ever to come over the Oregon Trail gravitated to this section of the Oregon Territory. Wherever they settled they started a school and a church. Many of them were members of the Christian Church.

It was only natural that a circuit rider preacher, Elder Glen O. Burnett, should call the people of this religious communion together in a camp meeting in an oak grove near Bethel in 1852. At this meeting the idea of Bethel College was conceived.

In 1851 a physician and surgeon, Dr. Nathaniel Hudson, took a land claim in this “Athens of the West.” The first thing he did was to build a log schoolhouse; and in the late spring and early summer of 1852, he held the first public school in the area. Because of his 27 superior education, the Doctor was able to teach the higher branches of education which was not possible in most of the pioneer schools.

In 1854, Dr. Hudson sold his squatters’ rights at Bethel and took a claim two miles west of Dallas. The pioneer families about Bethel had come to depend fully on Dr. Hudson’s school, and its loss was a severe one to the whole community.

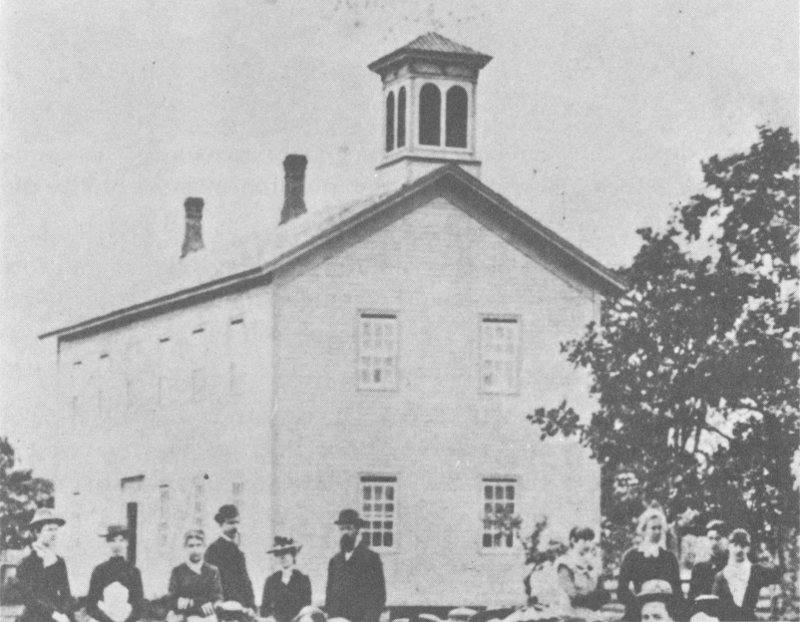

Two Christian preachers, Amos Harvey and Glen O. Burnett gave 261 acres of their donation land claims for the financing of Bethel Institute, later Bethel College. This was near the first of the year in 1855. A two-story frame building, 36 × 44 feet in dimension, was proposed. From March until July 4, 1855, materials were gathered on the grounds for the college building “raising.”

On the “glorious Fourth of ’55,” men with their families in wagons began arriving. Some came from great distances. Besides carpenter work, there was a sermon, a patriotic address, and a basket dinner. At the close of the day, the main framework of the building, with its roof in place, was done. The building was finished and dedicated, October 22, 1855. Bethel Institute was chartered by the Territorial Legislature on January 11, 1856. Four years later, on October 19, 1860, Governor John Whiteaker signed the charter of Bethel College, which has never been revoked.

Although for many years Bethel College has ceased to function as far as actual classes are concerned, it still exists. It has a board of trustees, and owns the college property—the ground on which Bethel Elementary Grade School is located. It elects a board of trustees each year, and has the power to grant degrees.

Too little is known about this college which gave Oregon one governor; the wife of a United States Senator; and many who later became lawyers, school teachers, and clergymen. One of the founders of Bethel College, Amos Harvey, gave to the United States Senate his great-granddaughter, the Honorable Maurine Neuberger.

Each year in midsummer the alumni association and the descendants of the pioneers of Bethel gather on the grounds for an all-day picnic and annual meeting.

In Waverly, Ohio, Nicholas Lee and Sarah Hopper were married August 4, 1840. That same year they moved from Ohio to Iowa, while Iowa was still a territory. In the spring of 1847, they left for Oregon, fully equipped with a good team of oxen, two cows (Rose and Lilly) and necessary household goods. Raids by Indians upon the cattle of the train and losses by stampedes left them practically without a team. They threw away much of the household goods and fortunately purchased a yoke of oxen (Dave and George) from another train, enabling them to complete the journey.

The Lees and quite a number of others took the Southern route via Klamath Lake and Cow Creek Canyon. Of the train coming down the Columbia, several stopped at Dr. Marcus Whitman’s station and were ruthlessly murdered or captured in the Indian massacre of November 29 and 30, 1847.

It was late in the fall when the Lees reached the head of the Willamette Valley, for the trip was a hard one, especially Cow Creek Canyon. The cattle were weak and jaded. Elias Briggs, who had safely brought a hive of bees that far, lost them when his wagon was overturned in the water.

The Lees and James Fredericks selected claims and built cabins not far from Eugene Skinner’s, after whom the city of Eugene was named. In the spring of 1848, Frederick and Lee with their families 29 came to Polk County, seeking work and supplies. Their intention was to return, but hearing that the Indians had burned their cabins they decided to remain. They had the use of a two-room cabin for a time.

The winter of 1848 and 1849 was spent by the Lees in Salem. The California gold rush was on, and Mr. Lee, a cooper by trade, made pack saddles that winter and sold them to men leaving for the mines.

In the summer of 1849, they returned to Polk County and bought a claim two and one-half miles south of Dallas. The transition from the cabin to the “new house” was an important event with the pioneer family in 1852. The house is still in use but has been remodeled. Mr. Lee took an active part in establishing church and schools in Dallas and its area. In 1854, he was licensed as a preacher of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and is credited with organizing the original Methodist Society.

In 1855, Mr. Lee took the lead in building a log school house on the John Nicholas place. His two older children attended. Soon afterwards a move started for an independent academy in Dallas. Lee was one of the members of the first board of trustees, and served as treasurer. Land and money were donated, and the town site was moved from the north side of La Creole Creek to the south side.

In 1856-57 were built the new courthouse and jail. The La Creole Academic Institute had two rooms ready for school opening, February 15, 1857. Professor Horace Lyman and Miss Lizzie Boise were the teachers. The Lee children, as they grew large enough, walked three miles to school. To give the children advantage of winter school, Mr. Lee built a house in Dallas, which they occupied at times until the fall of 1862, when Mr. Lee started a small store in Dallas and they moved to town.

The Academy served as a school for all age groups until the 1880’s. The first public grade school building was erected about 1882.

In 1900, La Fayette Seminary, organized by a board of trustees of the Educational Association of the Evangelical church, was incorporated with La Creole Academic Institute in Dallas. It was known as Dallas College and La Creole Academy. The combined schools were endowed by the church. A dormitory was erected in 1900, costing $3000. The Woolen Mill property was purchased for $1,500, and—for the expenditure of about $1,000 in repairs and remodeling—the second floor was converted into a good gymnasium.

The schools closed in 1914 for lack of funds to meet the requirements of Oregon standardization laws.

David Stump, of Pennsylvania Dutch stock, was born in Ohio on October 20 (or 29) 1819. As guard, outriding scout and hunter, he came to Oregon with the immigrant train of 1845. An experienced surveyor, his services were in demand for surveying the virgin territory of what is now Benton, Polk, and Yamhill counties. In 1851, he was married to Catherine Elizabeth Chamberlin, who had come, a child of nine, with her family in the wagon train of 1844.

David and Catherine Stump took up a donation claim on the Luckiamute River, six miles south of what later became the village of Monmouth, being among the very first settlers in that part of the Willamette valley. Here they prospered. They became devoted and loyal members of the Christian Church, which soon established a church-supported college in Monmouth. There were two sons and two daughters. When these were ready for higher education, David Stump acquired from the Lindsay family a home in Monmouth adjacent to the college. It stood at the intersection of Jackson and Monmouth streets on the southwest corner of a half-acre tract of land, facing to the west the Victorian Wolverton place, with the Orville Butler home to the north. This became—and continued for many years as—the Stump family home. Here, after a long illness, David Stump died on February 21, 1886.

In the mid-nineties the house was completely renovated and, to a great extent, rebuilt. The roof was raised to give space for a large 31 attic. Rooms and porches were added. The position of the entrances and chimneys was altered. In all, there were now seventeen rooms. Miss Ellen Chamberlain, Mrs. Alice Applegate Peil, Miss Antoinette Bruce, Miss Rose Bassett, Miss Lane, and other members of the Normal faculty lived there around the turn of the century. It became quite a center of college activities. Miss Cassie B. Stump had inherited the property from her father.

There was a good-sized barn at the east end, occupied by a Jersey cow and chickens and ornamented in Autumn with the glowing red of Virginia Creeper. There were a berry patch, a large vegetable garden with morning glories twining the corn stalks, and a row of huge sunflowers. Mrs. Stump and her daughter were great lovers of flowers. They had a small greenhouse for chrysanthemums, smilax, cacti, and various exotic plants. A gnarled Gravenstein produced great, juicy apples. There was a big white fig tree, which froze to the ground periodically, but somehow managed to survive. Directly behind the house stood two exceptionally tall Black Republican cherry trees, a rare sight when in bloom and by July covering the ground inches deep with an over-abundance of ripe fruit. There were madonna lilies, amaryllis, the spike of a yucca, and roses in profusion. A sweet Mission rose, brought to the farm from California, then transplanted to town, was by the front door. Inspired by a visit to the poet, Longfellow, during her student days at Wellesley college, Miss Stump had planted a hedge of lilacs modeled after his in Cambridge.

Not long after Miss Cassie Stump’s death in 1941, the property was acquired by the Oregon College of Education. The old house, by now in a state of disrepair, and the once lovely garden, neglected and overgrown, were removed to make way for the handsome, modernistic library building and the appropriate landscaping with which it is surrounded. A Jack pine and the great maples across the front are about the sole reminders of the former occupancy of the land.

A collection of pictures, records, and mementos of early days at the college is housed in the library. It seems eminently suitable that this particular site should become a permanent part of the campus of the school, in the founding and support of which the Stump family had had such a large share and in which the members had maintained a vital interest over so many years.

The early settlers in the Willamette Valley were not only provident and God-fearing, they were also deeply concerned with higher education for their young people. Academies and colleges sprang up in many of the valley communities. A group of prosperous farmers in Polk County, consecrated members of the Christian Church, gave land and financial support to found a church-affiliated school at Monmouth, to become known as Christian College.

In 1869, Thomas Franklin Campbell was engaged to head this institution. Originally from the deep South, he had come some years previously to Helena, Montana, where he conducted a school for boys and served as circuit judge. He was a man of wide interests and abilities, having served in the Mexican war, and been active as lawyer, minister, and promoter of various public projects. But he was before all else an educator. As a student at Bethany College in Virginia he had lived in the home of Alexander Campbell, founder of the Christian Church. There he had acquired an excellent classical education, had been ordained to the ministry, and had married a cousin of Alexander Campbell, only recently arrived from Ireland.

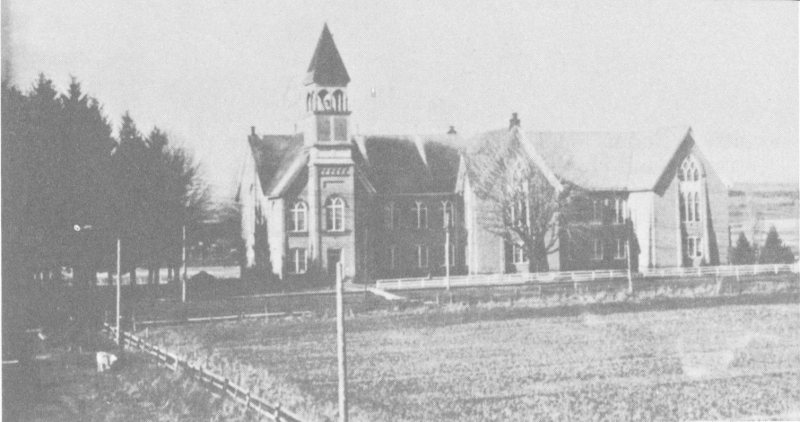

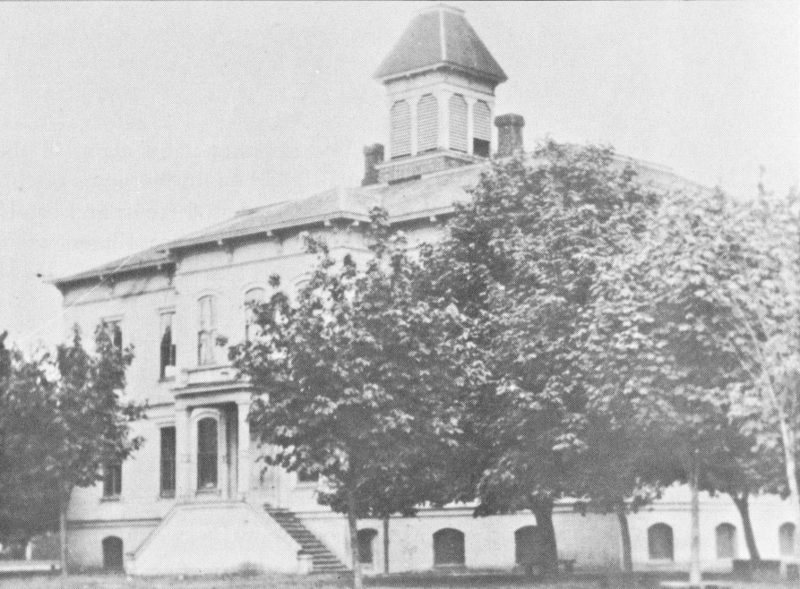

Responding to the call from Monmouth, with his wife, Jane Eliza and their three sons, he made the long, arduous trip from Helena to Oregon in a stagecoach. The challenging task for the 33 new administrator was to raise funds for a suitable, permanent structure. He solicited earnestly over the state and very soon a brick building, modelled as to general type after the Gothic-inspired architecture of Bethany College, was constructed. It was here that distinguished jurists and others prominent in Oregon life received a thorough grounding in the classics. The curriculum was mostly concerned with Greek, Latin, mathematics, logic, and philosophy. Science was not at that time, as it is with us, a prime consideration. The first graduating class was that of 1871.

By 1892, Christian College had been converted into a State Normal School. There was imperative need in the state to train teachers to meet the growing demands for their services. Prince Lucian Campbell, son of Thomas Franklin Campbell, was now the president. A new wing on the south was added to the original building. This included a science laboratory, several large classrooms, and an assembly hall known as “the Chapel.” The latter has undergone some changes and is at present called “Campbell Hall,” where hang the portraits of the two early presidents.

This new wing was surmounted by a bell tower from which the strong-toned bell peremptorily summoned students to their morning classes. Eventually the enlarged building was balanced with another wing added on the north to house a training school. The whole structure forms truly an historic Oregon Landmark, which is held in fond affection by the many who have studied there.

A sad mutilation occurred in the great wind of Columbus Day 1962. The familiar belfry was toppled to hang precariously. The forlorn picture was featured in newspapers and national magazines as evidence of the violence and destructive power of the unprecedented storm. Many great trees of the ancient fir grove and others on the campus were badly damaged. Much is irreparable, but effort is being made to replace the bell tower and to restore all possible.

The Oregon College of Education, with the other institutions in the State System of Higher Education, is experiencing a record enrollment. There are new and modern buildings to meet increasing demands. To foster tradition and the realization of past accomplishment, and to stress the foundation on which present achievement is based, the preservation and history of this original building at the Oregon College of Education is of signal importance.

The site of Fort Hoskins, Benton County’s first military post, was chosen by second lieutenant P. H. Sheridan with the help of Oregon Indian Superintendent, Joel Palmer. The name Hoskins was chosen by the Fort’s first commander, Captain Christopher Colon Augur, as his first official order, on July 26, 1856. For the next nine years Fort Hoskins served as the home and training ground of regular U. S. Army troops as well as volunteers from California, Washington, and Oregon. Although a few troopers from Hoskins knew some anxious moments in the early days, no shots were ever fired into or out of the fort in anger. In fact, the biggest argument to affect the Fort at any time was whether or not there was any excuse for its existence.

Fort Hoskins was located at the Middle Pass over the Coast Range of mountains to keep the surviving Indian participants of the Rogue River War on the reservation which General Palmer had prepared for them on the Oregon coast, near the present towns of Newport and Siletz. However, the post was so far—some thirty miles from the Indians—that a blockhouse had to be established on the upper prairie of the Siletz River. Fort Hoskins supplied men, munitions, and materiel for the blockhouse.

Of the later generals who served there, at least two became famous: Philip Sheridan, who located the site of the Fort and served as its first quartermaster and commissary of supplies; and C. C. Augur, who, during his five years in command, learned how to deal with his superiors the hard way—by letter. In the Civil War, Sheridan started his climb to fame as a commissary officer; and Augur, who had developed into a persuasive writer, not only won battles but served with distinction on many military courts and committees, where his early training in mental organization served him well.

Fort Hoskins also provided a training camp for western volunteers between 1862 and the end of the Rebellion, although few of the men who trained there ever heard the whir of Indian arrow or the whine of enemy shot. They did, however, learn the rudiments of the military discipline of living month in and month out with themselves and with crushing boredom. At first only a sutler’s store catered to the wants of the soldiers, but at length a Corvallis firm, hard on the trail of easy money, opened an establishment near the post that dealt in a commodity the sutler’s store was not allowed to sell: spirits.

No Indians ever tried to attack Fort Hoskins, but during the turbulent days of the Civil War, threats were made against the undermanned Fort by Secessionists, of which there were many in the immediate neighborhood. The nearest town of any size, Corvallis, was notoriously sympathetic to the cause of the South and was contemptuously known in other parts of the state of Oregon as the only town that ever had a Copperhead mayor. To make matters worse, this worthy was twice elected. Certain Southern sympathizers were organized into a secret state-wide society called the “Knights of the Golden Circle.”

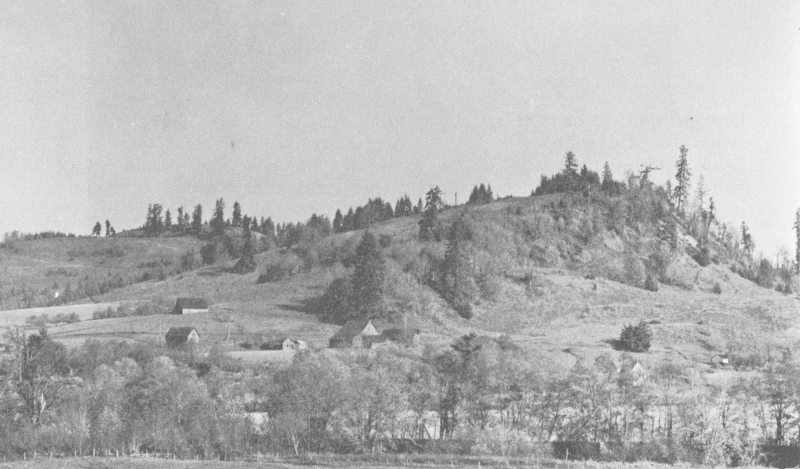

Fort Hoskins was permanently evacuated on April 13, 1865, the last company to leave being Captain Waters’ Company F of the First Oregon Volunteer Infantry. A year later the buildings were auctioned off, and the land, which had been rented, was returned to the owners. In the accompanying photograph, the cluster of unpainted farm buildings, left of center, stand on what was once the parade ground of Fort Hoskins. The large farmhouse behind the trees, at the right, rests on the site of the old hospital. On the light-colored field between the trees and the hill, soldiers once drilled and learned how to shoot at distant targets. Time and distance have lent enchantment, of a sort that never really existed, to the history of a lonely little frontier Fort in an all-but-forgotten corner of Oregon.

In 1858, the old Simpson’s Chapel was completed. It stood on a hill about halfway between the present towns of Bellfountain and Alpine. The church was built of hand-planed lumber and was a plain oblong with three windows on each side and a porch in front. It was surrounded by oak trees, many of which are still standing and which served as hitching posts for horses.

The history of the Alpine community may be said to have had its beginning at the time of the erection of two buildings, the Ebenezer school house and Simpson’s Chapel, though it is true that quite a number of settlers had come to the valley before that time. The school house was built of logs and was situated on a promontory about two miles south of the present town of Alpine and on part of the old Gilbert place. It was probably built about 1849 and served both as a school and a “meeting house.”

It was and always has been a Methodist Church and was called Simpson’s Chapel because Bishop Simpson was the presiding officer of the first annual conference, held while the group was still meeting in the old Ebenezer school. In 1903, it was decided that a new church was needed, so one was built at the present site of Alpine and was completed in 1904. At this time the congregation divided, part of its members going to Bellfountain and part to Alpine.

The whole community was once known as the Belknap settlement because of the preponderance of Belknaps among the first 37 settlers who, in pioneer days, had come by wagon train to the valley from Ohio, Missouri, and Iowa. Other early families were the Starrs, Hawleys, Howards, Gilberts, Catons, Woodcocks, Goodmans, and Nichols.

Another interesting part of the early history of the Chapel centered around the campground which, in 1871, was bought from George Humphrey and is known as the Bellfountain Park. People came from miles around, primarily for the spring of clear cold water, held meetings, and visited. The gatherings were religious but also social. People would bring food, put up tents, and stay for a week or more. Sometimes someone would bring part of a beef and hang it on a tree and those present were free to help themselves. The pioneer days are gone but Simpsons Chapel is still used as a house of worship by those who have taken the place of the pioneers.

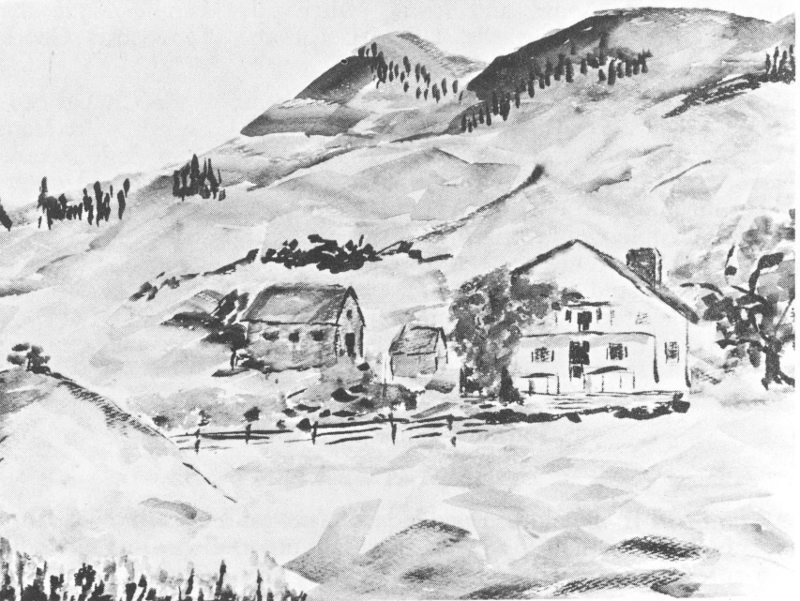

Painting by Lucia Moore.

In 1847, Mitchell Wilkins and his young wife, Permelia Ann Allen, then eighteen, arrived on foot at “The Falls.” He was twenty-nine. Their wagon, plus goods and tools, were beside the Barlow Road with the last-dying oxen. Permelia’s father Robert Allen, still driving wagon and ox team, made their last miles easier. The three pushed on from Oregon City toward Silverton and, on October 1, came to Butte Creek. There they halted to build cabins, plow, and plant. Ten months later my father was born. When the baby, Francis Marion, was two months old, Mitchell Wilkins took a land claim in upper Willamette Valley, edging the Coburg hills. During the sixty years he lived there, the 640 acres grew to 20,000.

The pioneer home which replaced the original cabin was of southern origin for Grandfather was of North Carolinian stock. Built in 1854, it was low and wide with a small gallery above and a wider one below facing the west and overlooking Centennial 39 Butte where, in 1876, Mitchell Wilkins planted maple and fir trees. He carried water by sled to the butte’s very top to make sure the trees would live. They stand, to the present day, like a tuft of hair on an Indian’s skull.

Willamette Forks post office was housed in one of the small outer buildings, bringing neighbors together when stage or pony rider dashed past on East Side Territorial Road, dropping off mail. “Late news” was at best a month old but worth discussion as the years brought disunion and secession problems to be faced among southern democrats and members of the newly organized Republican party. Indians had made the hillside trails which were to become the Territorial Road, and Calapooias still roamed the trails and dug camas roots in the blue-flowered fields.

When the Wilkinses built a cabin, there was not yet a Eugene village. Mr. Skinner had only just brought his family to a sheep-herder’s cabin on the butte called Ya-po-ah, and had hardly formed his dream for Eugene City. That town would one day be ten miles south of the Wilkins home.

The land proved out Mitchell Wilkins’ plan for raising fine grain and fine cattle. He took his prize grains to Philadelphia’s Centennial in 1876, New Orleans Exposition and Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, returning with honors for Lane County and Oregon. He served in the State Legislature, 1862-64, there presented Eugene’s petition for incorporation, and was instrumental in its passage. He was one of the men who organized Oregon’s Agricultural Society and Fair, which became the State Fair. He served as an early president and on its board until paralysis forced him to give up all activities. Inaction was hard for the tall, eager-eyed Scotsman, but he endured it with a smile, though he was unable to speak.

He had lived a full life. He had been a member of the “Union Club,” a Civil-War-time club of Lincoln and Union enthusiasts as determined and as secretive as the members of the secessionist “Knights of the Golden Circle.” He saw the Union saved, saw Lincoln elected; and rode the secret trail to the James Daniels house in the hills where a few men swore allegiance by candlelight. My father, at 13, was allowed to go there because he knew the words to John Brown’s Body. Oregon, a baby state, was half inclined to secede and could not have supported Lincoln except for a division among its Democrats—the loyalty of southerners like Mitchell Wilkins who had come to settle in this Willamette Valley and who did not want slavery for the West.

Oregon Historical Society

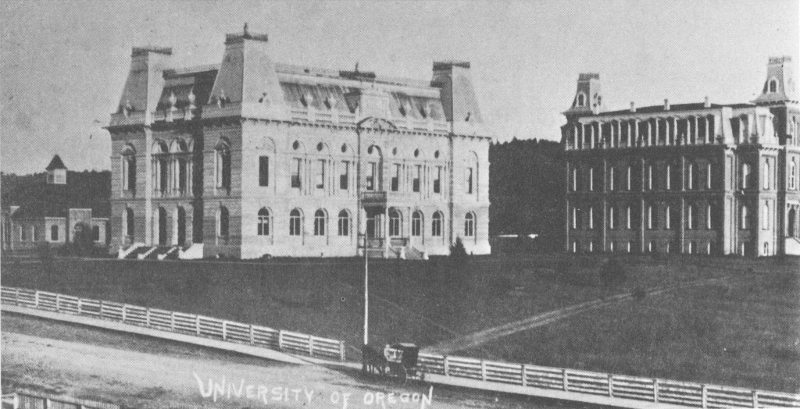

Deady Hall, the first building of the University of Oregon, was the realization of a great dream. In 1803, a Government policy was declared for the purpose of establishing State universities, this to apply to any state entering the Union after that date. Forty-seven years later, in 1850, by a donation land act, the Territory of Oregon was given this grant.

At first, state politicians handed the Capitol to Salem, the Penitentiary to Portland, and the University to Corvallis; then later it was promised to Jacksonville. The controversy grew bitter, the arguments so strong in every direction that the issue finally died of overdoing.

In 1857, Judge Matthew P. Deady, a southerner and President of the State Constitutional Convention, was much in favor of the parochial school system, though later he was one of the most loyal supporters of the University. Mr. R. S. Boise of Salem, with a large group of northern followers, felt the state should have one nondenominational school of importance, with lower fees, so the political dickering continued. By 1872, the issue had built up in tension and was again a red-hot argument.

On a July night of that year, a group of five men met to discuss again the need of adequate schools. In the old McFarland home on Charnelton street, kerosene lamps burned into the morning hours, and the young be-whiskered gentlemen discussed the good of future generations. They were B. F. Dorris, S. H. Speence, John M. 41 Thompson, Judge J. J. Walton, and John C. Arnold. Later, J. S. Scott, J. B. Underwood, S. S. Comstock, A. S. Patterson, E. L. Bristow, E. L. Applegate, and Dr. A. W. Patterson joined them to organize the Union University Association. John Thomas was elected President, and T. G. Hendricks, Treasurer, while Walton, Dorris, Scott, and Abrams formed the first board of directors. This board appeared before the next meeting of the State Legislature to present a bill permitting purchase of a site for the erection of the first building on the new University campus. Fifty thousand dollars was allowed for Deady Hall, to be completed and turned over to the State in January, 1874. The bill also provided for a Board of Regents of nine—six to be appointed by the governor and three by the association itself. State scholarships were to be awarded by counties and forbade any sectarian or religious tests for either students or instructors.

Again plans ran into trouble. Outside interests appeared declaring the location bill unconstitutional because “all state institutions were to be located in Salem.” Again the pioneers fought for their rights with good arguments; increased population, high standards of living, value of land, and so on. In spite of all the evidence, opposing elements obtained a revocation of the bond issue, and only private subscriptions saved the university.

Committees were appointed for selection of the best site, and ways of raising money. The final choice was left to the State board of commission, which meeting in Eugene “found the fine view from the Henderson property most to their liking” so, in April of 1873, their selection was made of this thirteen-and-three-fourths-acre tract.

The University was at last on its way, but it proved to be a very rough road.

Plans were for a thirty-thousand-dollar bond issue by the courts, with twenty thousand to be raised by private subscription. The financial panic was on. Cash was scarce. Subscriptions came in slowly. There were loud protests at tax time! But plans never stopped: of the two hundred families making up the listed population, one hundred and forty names were on the subscription list, many of them for labor and farm produce. Thomas Judkins sold land at six dollars an acre, the proceeds to go to the building. Churches helped out with suppers and strawberry festivals.

At last Deady Hall was completed—as far as the roof, when again money ran out and again citizens dug deep in their pockets to complete the tall stately building, the first of the new University.

Boychuk Studio

Applegate, one of the most famous names in Oregon history, belongs to a family whose origin was English. As early as 1635, there were Applegates who came to New England, and from there they went to New Jersey, thence to Maryland, and on to Kentucky in 1784.

In 1843, three Applegate brothers, Charles, Jesse and Lindsay, became greatly interested in the far Oregon country and made their departure from Missouri (Independence). Jesse’s experience had included school teaching, sawmill operation, and an important position in the Surveyor General’s office in St. Louis, Missouri. All this fitted him admirably for the role of trail blazer, pioneer, and train leader, which he was to assume.

Those with blooded stock elected Jesse Applegate as Captain of the now famous “Cow Column.” He was ably assisted by his brothers Charles and Lindsay. With the Looneys, Waldos, Nesmiths, Fords, Kaisers, and Delaneys, they pressed on and in time, assisted by Dr. Whitman, arrived at the mission in October, 1843. After leaving Fort Hall, they blazed their own trail—and finally arrived safely in the Willamette Valley. They discovered that the powers in the East refused to give aid to the new settlements because England held the Columbia and there was no other means of ingress to the country for soldiers. The Applegate brothers decided they 43 would provide one, and that from the south. They asked Levi Scott, a brave and trusted man, to lead it. Before the party crossed the Callapooya it fell out and began straggling back. The Applegate brothers met and gathered them together as they returned.

Jesse was elected Captain, with Lindsay second in command. Charles remained at the settlement to look out for several families of small children and their mothers, as well as to watch the crops and to be alert for Indian attack. The party left on June 22, 1846, to locate and open a southern route to the Willamette Valley. They returned in late October. Over one hundred wagons made this historic trip.

Jesse served in the Provisional Legislature from 1845 to 1849. Later he became Indian agent and candidate for the U. S. Senate. In 1849, he settled in the Umpqua Valley, where Charles also decided to make his pioneer home. Lindsay settled in what is now the Ashland area. The Charles Applegate house is one and one-half miles northeast of the town of Yoncalla, and was completed in 1856. The home faces the south and is surrounded by stately trees. Many shrubs still bloom in the garden which were planted by Melinda.

The structure is two and a half stories, and the lumber for it was cut by Washington Cannon of Scotts Valley. Many of the timbers were hand hewn and the chimney brick were burned on the grounds. A long veranda, with balcony above, was built under the overhanging roof. The first floor contained two large rooms with sizeable fireplaces in the middle, opening into each room, and a front door opening out onto the long porch. The west room was formerly known as “Grandmamma’s room.” To the east were the living room, sewing room, dining room, and kitchen. Each of these had heavy beamed ceilings. There were, in those early days, small winding staircases rising in the fireplace corners, and a landing near the chimney in the center of the house above the staircase. Upstairs the design was much the same. There were two large rooms, both opening out onto the balcony. Alongside them and above the dining room were four small bedrooms with attractive nine-paned windows.

Fifteen sons and daughters grew up in this historic house. Uncle Charley’s home, being centrally located, was the gathering place of all the Applegate clan. Today the home is owned by Miss Eva Applegate, a direct descendant. The home has never been sold to others in over 105 years.

Boychuk Studio

One of Lane County’s most historic, most well preserved, and architecturally charming houses is that known as the Cartwright place or Mountain House hotel. It is located on the Old Territorial Road, three miles south of Lorane, Oregon, and is now the property of Mr. and Mrs. Eldon Thompson.

It was built in 1853 by Darius B. Cartwright. Dee, as he was familiarly known, was born near Syracuse, New York, February, 1814. In 1832 he served in the Black Hawk War. Some years later his family moved to Illinois. Here a brother, Barton, became a Methodist circuit rider who saw to it that his family had educational opportunities, one son becoming an early-day judge.

Darius B. Cartwright with his wife and several children left Illinois for the gold rush in California in 1849. Sometime later they pressed on to Oregon, remaining for a time near what is now Medford. In 1853, the family took up 530 acres near what is now Lorane and called the location Cartwright. Upon this beautiful site was built the fine home which was also to serve as a stagecoach inn, the official stop between Portland and San Francisco, a telegraph 45 station and a post office, with Mr. Cartwright as postmaster. One of the first messages received over these wires during the Civil War was that of the assassination of President Lincoln.