Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

DEDICATION

To my parents who encouraged my interests in mushrooms and toadstools and my wife who, later, was sympathetic to my studies and assisted in the production of the manuscript.

Hulton Group Keys

IDENTIFICATION OF THE LARGER

FUNGI

by

ROY WATLING, B.Sc., Ph.D., M.I.Biol.

Principal Scientific Officer,

Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh

Editor of series: Antony R. Kenney, M.A., B.Sc.

©

1973

R. Watling

A. R. Kenney

ISBN 0 7175 0595 2

First published 1973 by Hulton Educational Publications Ltd.,

Raans Road, Amersham, Bucks.

Reproduced and printed by photolithography and bound in

Great Britain at The Pitman Press, Bath

[5]

This is one of a series of books intended to introduce field-biology to students, particularly the sixth form and early university student. The present work is ecologically biased in order to emphasise a rather neglected aspect of the higher fungi.

Few books on fungi have ever been designed for students. This book is aimed primarily at this level, but if the interested amateur is assisted and encouraged by this same text my hopes will have been doubly achieved. Many amateurs interested in higher fungi wish only to name their collections, or know approximately what they are before sampling them as an addition to their diet. An understanding of our commoner species at an early age will allow the ‘budding’ mycologist to tackle the much needed study of the more critical forms. Mycology is still at a descriptive stage, but it is hoped this will soon be changed and fungi of all kinds will be studied as part and parcel of courses in ecology.

It is of course quite impossible to cover all the species in such a small volume as this present one, but it is hoped that the examples which have been carefully chosen are sufficiently common throughout the country for any student to collect them in a single season. The examples, except for very few, in fact appear in the list of higher fungi found about the Kindrogan Field Centre, Perthshire, Scotland, compiled from the collections made by students attending my field course there.

The present work is arranged in three parts: the agarics are dealt with first, the non-agarics next, both with particular reference to their major habitat preferences, and lastly a catalogue of those more specialised habitats which are frequently encountered. All parts are supported at the end by lists in tabular form of those species expected to be found in any one habitat. Keys to the major groups, families and genera, are included to widen the scope of the book and place the examples chosen and illustrated in the text in their position in classification.

In the description the synonymy has been very severely pruned and only covers the commonly seen names; they are included as part of the general information under each species. In order for the student[6] to expand unfamiliar names a list of references is added at the end of the work. The common names of the fungi, whenever possible, have been adopted from a list produced by Dr Large, the author of The Advance of the Fungi, an exciting tale of fungal parasites. The authorities for the names of the fungi described have been reduced to accord with the minimum requirements set out by the Code of Botanical Nomenclature. After each description a list of references to coloured plates is given and while some of these illustrations are not of the highest quality they are adequate, and, more important, they are widely available. Any technical terms appearing in the description are explained in the glossary, although they have been kept to a minimum; the difficulty of expressing colours has been overcome by consistently referring to one colour chart only, (a chart designed originally for the use of mycologists and available from Her Majesty’s Stationery Office).

I have not indicated the edibility of a particular species unless there is no doubt as to the edibility of it, related species and those species with which it might be easily confused. Many fungi are notoriously difficult to identify and when one has approximately 3,000 species of larger fungi in the country the task is even more difficult. It would be folly therefore to indicate edibility for all the fungi described in a book such as this; the golden rule which should be adopted is not to eat any of the fungi one collects in the woods and fields. A fault of most popular treatments is that they are biased towards the human diet and selection of species is done on this basis; in the present work selection of examples within the 270 pages has been difficult and two factors have been particularly considered to ensure that (i) representatives of all the major groups of fungi and genera have been covered and (ii) a coverage has been attempted of all the common ecological niches.

I am fully aware that the taste of a fungus may be distinctive to that species or to a group of closely related species, but it is only a spot character and the tasting of one’s finds is neither necessary nor advisable; indeed it is not used in this book. The odour, however, has been indicated whenever distinctive.

[7]

| Page | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preface | 5 | ||||

| Introduction | 9 | ||||

| Where to look | 9 | ||||

| Collecting | 10 | ||||

| Examination | 11 | ||||

| Microscopic examination | 12 | ||||

| Key to major groups of Larger Fungi | 21 | ||||

| A. | Agarics and their relatives | 22 | |||

| Key to major genera | 22 | ||||

| (i) | Agarics of woodlands and copses | 27 | |||

| (a) | Mycorrhizal formers | 27 | |||

| (b) | Parasites | 59 | |||

| (c) | Saprophytes—Wood-inhabiting or lignicolous agarics | 64 | |||

| (d) | Saprophytes—Terrestrial agarics | 78 | |||

| (ii) | Agarics of pastures and meadows | 95 | |||

| (a) | Agarics of rough & hill-pastures | 95 | |||

| (b) | Agarics of chalk-grassland & rich uplands | 108 | |||

| (c) | Agarics of meadows and valley-bottom grasslands | 114 | |||

| (d) | Fairy-ring formers | 118 | |||

| (e) | Agarics of urban areas—lawn and parkland agarics | 122 | |||

| (f) | Agarics of wasteland and hedgerows | 126 | |||

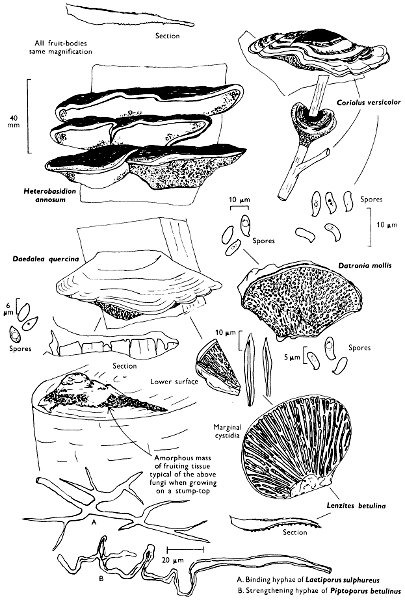

| B. | Bracket fungi and their relatives | 135 | |||

| Key to major genera | 135 | ||||

| (i) | Pored and toothed fungi | 140 | |||

| (a) | Colonisers of tree trunks, stumps and branches | 140 | |||

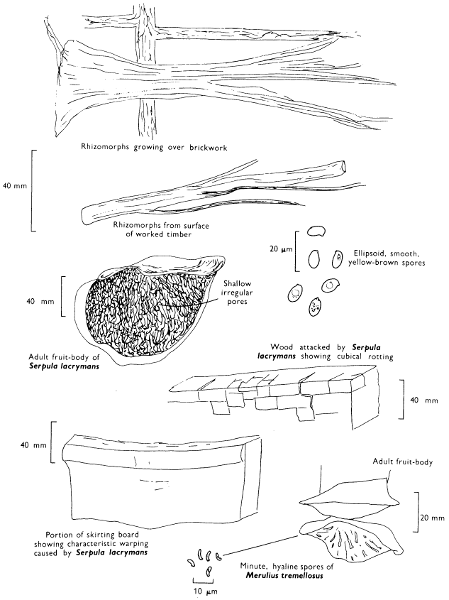

| (b) | Destroyers of timber in buildings | 154 | |||

| (c) | Colonisers of cones | 158 | |||

| (d) | Terrestrial forms | 160 | |||

| (ii) | Cantharelles and related fungi | 162 | |||

| (iii) | Fairy-club fungi | 166 | |||

| (iv) | Resupinate fungi | 176 | |||

| C. | The Jelly fungi—Key to major groups with examples | 179 | |||

| D. | The Stomach fungi; puff-balls and their relatives—Key to major groups with examples | 186 | |||

| E. | Cup fungi and allies[8] | 198 | |||

| F. | Specialised Habitats | 207 | |||

| (i) | Fungi of dung and straw heaps | 207 | |||

| (ii) | Fungi of bonfire sites | 216 | |||

| (iii) | Fungi of bogs and marshes | 222 | |||

| (a) | Sphagnum bogs | 222 | |||

| (b) | Alder-carrs | 226 | |||

| (iv) | Fungi of beds of herbaceous plants | 227 | |||

| (v) | Fungi of moss-cushions | 230 | |||

| (vi) | Heath and mountain fungi | 231 | |||

| (a) | Moorland fungi | 231 | |||

| (b) | Mountain fungi & Basidiolichens | 236 | |||

| (vii) | Sand-dune fungi | 238 | |||

| (viii) | Subterranean fungi | 243 | |||

| (ix) | Fungal parasites | 246 | |||

| G. | Appendix | 249 | |||

| (i) | Species lists of specialised habitats | 249 | |||

| (ii) | Glossary | 260 | |||

| (iii) | Simple experiments with Fairy-rings | 264 | |||

| (iv) | Development of the Agaric fruit-body | 266 | |||

| (v) | References | 269 | |||

| H. | Index | 271 | |||

Cover transparency supplied by John Markham, F. R. P. S., F. Z. S.

[9]

The term larger fungus refers to any fungus whose study does not necessarily require more than a low-powered lens to see most of the important morphological features. Using such a term cuts across the existing scientific classification, for it includes the more obvious fungi bearing their spores on specialised reproductive cells called basidia, fig. 5, and a few of those whose spores are produced inside specialised reproductive cells called asci. The term is useful, however, even though it embraces a whole host of unrelated groups of fungi; it includes the polypores, fairy-clubs, hedgehog-fungi, puff-balls and elf-cups, as well as the more familiar mushrooms and toadstools—or puddockstools as they are often called in Scotland. Specimens of all these groups will find their way some time into the collecting baskets of the naturalist when he is out fungus-picking, along with probably a few jelly-fungi and less frequently one or two species of the rather more distantly related group, the morels. The biggest proportion of the finds, however, on any one collecting day in the autumn, when the larger fungi are in their greatest numbers, will be of the mushrooms and toadstools; these are, collectively, more correctly called the agarics.

The early botanists and pioneer mycologists of the nineteenth century recognised the fact that the fungi both large and small are ecologically connected to the herbaceous plants and trees among which they grow, but many mycologists since have tended to neglect these early observations. Although the importance of the fungi in the economy of the woodland, copse, field and marsh is well-known, mycologists and ecologists alike have been rather slow to appreciate that the fungi can be just as good indicators of soil conditions, if not better, than many other plants. Perhaps it is rash to attempt such a treatment as you find here because we know so little of the reasons why a particular fungus prefers one habitat to another. However, it is envisaged and hoped that, if a framework is provided, accurate field-notes can gradually be accumulated and many of the secrets yet to be uncovered explained.

Fungi can be found in most situations which are damp at some time of the year. Searching for fungi can begin as soon as the spring days become warm, although even in the colder periods of winter several[10] finds can be made. In summer it gets very dry and this necessitates collecting in damper areas, such as marshes, alder-carrs, swamps and moorland bogs. After a heavy storm in summer, on the edges of paths and roadsides, woodland banks, in clearings in woods and in gardens, fungi can be collected within a few days of the rain, but collecting normally reaches a climax in August-September, the precise date depending on the locality and the individual character of the particular year.

All woodlands are worth visiting, particularly well-established woods with a mixture of trees. Pure pine-woods do not seem to be as good as pine-woods with scattered birch; plantations are often disappointing except after heavy rain or late in the season, even well into November in mild years. Pure birch and beech, the latter particularly when on chalky soils, are excellent areas to visit. Oak is possibly not as good but areas with willow and alder have many unique species. The edge of woods, sides of paths or clearings are usually more productive areas to search in than is the depth of the wood, and a small plot of trees can be much more rewarding than a large expanse of woodland. After some time one is able to judge the sort of place which will yield fungi. Rotten and burnt wood are very suitable substrates for they retain the moisture necessary for growth of fungi even in dry conditions, so allowing fructification to take place.

Grasslands including hill-pastures, established sand-dunes, etc., are often excellent, but of course they are much more dependent on the weather to produce favourable conditions for fungal development than woodland areas where the changes in the humidity and temperature are less extreme; prolonged mist or mild showery weather favour the fruiting of the grassland fungi. Dung in both woods and fields is an excellent although ephemeral substrate; many species of fungi characterise dung whilst others will grow in manured fields, on straw-heaps or where man has distributed the habitat.

The collecting of larger fungi should not be considered a haphazard pursuit; careless collecting often results in many frustrating hours being spent on the identification of inadequate material, which is also not suitable after for preservation as reference material. A few good specimens are infinitely better than several poor ones; one is always tempted to collect too much and then collections are inevitably discarded. Always try to select specimens showing all the possible stages of development[11] from the smallest buttons to the expanded caps. Sometimes such a range is not possible and one must be satisfied with either a couple or only one fruit-body.

Carefully dig up or cut from the substrate the entire fungus and handle it as little as possible. A strong pen-knife or fern-trowel is admirable for the job. The associated plants should be noted, especially trees, and if one is unable to identify the plants or woody debris retain a leaf or a piece of wood for later identification. One should note in a field-notebook any features which strike one as of interest, such as smell, colour, changes on bruising, presence of a hairy or viscid surface.

For transporting home the specimens should be placed in tubes, tins or waxed paper which are themselves kept in a basket. The smallest specimen can go in the first, the intermediate-sized forms in the tins or waxed paper and the larger ones laid in the basket or placed in large paper bags; plastic bags are not suitable except for very woody fungi. Thus an assortment of tins, tubes and various sizes of pieces of waxed paper are essential before setting out on a collecting trip. The specimens should be placed in the waxed paper such that they can be wrapped once or twice and the ends twisted as if wrapping a sweet.

Once home always aim at examining the specimens methodically.

The first necessity is to determine whether the fungus, which has been collected, has its spores borne inside a specialised reproductive cell (ascus) i.e. Ascomycete, or on a reproductive cell (basidium) i.e. Basidiomycete. By taking a small piece of the spore-bearing tissue, mounting in water, gently tapping it and examining under a low power of the microscope this can be easily ascertained. The tapping out is best done with the clean eraser of a rubber-topped pencil. There are several different shaped asci and basidia; the latter structures are more important in our study because the Ascomycetes are in the main composed of microscopic members.

The following procedure is necessary for the examination of your find:—

Select a mature cap of an agaric from each collection, cut off the stem and set the cap gills down on white paper, or if the specimen is small or is a woody or toothed fungus, or consists of a club or flattened irregular plate, place the spore-bearing surface (hymenium) face down on a microscope glass slide. The smaller specimens must be placed in tins with a drop of water on the cap to prevent drying out. Even with[12] the larger specimens it is desirable to place a glass slide somewhere under the cap between the gills and the paper, and if possible to enclose the species carefully in waxed paper or in a tin. Whilst you are waiting for the spore-print to form, notes must be made on the more easily observable features; one is not required at this stage to examine the microscopic characters.

All the characters which may change on drying must be noted immediately, and these include colour, stickiness, shape, smell and texture. A sketch, preferably in colour, however rough, can give much more information than many score words.

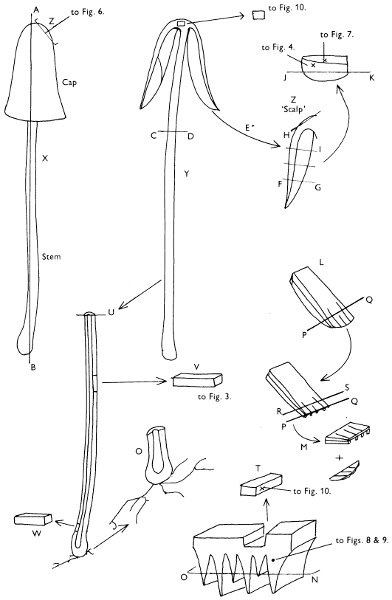

Cut one fruit-body, longitudinally down with a razor or scalpel or a sharp knife if the fruit-body is woody, and sketch the cut surfaces, fig. 1A-B. These sketches and the rest of the collection notes should be made such that identification and future comparisons can be achieved. Thus always note the characters in the same order for each description. A table of the important characters is provided here, but this is meant as a guide not as a questionnaire. The attachment of the gills, pores or teeth to the fruit-bodies when once the fungus is in section should be always noted (see p. 20).

The spore-print when complete should be allowed to dry under normal conditions and then the spore-mass scraped together into a small pile. A microscope cover-slip should be placed on the top of the pile and lightly pressed down. The colour of the spore-print (or deposit) can then be compared with a standard colour chart and the spores making up the print examined in water under a microscope.

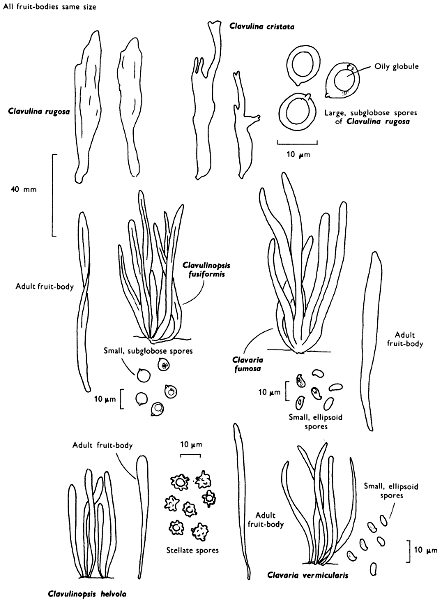

When one is more experienced with fungi it will be found necessary to carry out many microscopic observations, but when commencing the study it is necessary only to have an ordinary microscope; a calibrated eyepiece-micrometer is an advantage as is an oil-immersion lens. An examination of the spores is always necessary; the examination of features such as the sterile cells on the gill and stem, etc., varies with the fungus under observation. Spores should if at all possible be taken from a spore-print and mounted on a microscope slide, either in water or in a dilute aqueous solution of household ammonia. Although for mycologists it is often necessary to measure spores to within a 1⁄2 micron (µm) this book has been so arranged that one only really has to distinguish between a spore which is small (up to 5 µm), medium (5-10 µm), long (10-15 µm), or large if globose and very long (if over 15 µm); this is not strictly accurate, but serves the purpose for an introductory text. It is important to describe the character of the spore, i.e. ornamentations, whether a hole (germ-pore) is present at one end and/or a beak (apiculus) at the other (fig. 5). With white or pale coloured spores it is useful to stain either the spore or the surrounding liquid with a dye—10% cotton blue solution is admirable, or a solution of 1·5 g iodine in 100 ml of an aqueous mixture containing 5 g of potassium iodine and 100 g of chloral hydrate. Both these dyes must be accurately made up if the study of the fungi is to be taken at all seriously; because some of the chemicals used above are not normally required by students, a chemist must make up the reagents for you. Often the spores turn entirely or partially blue-black or pale blue or purplish red in the iodine solution—a useful character.

[13]

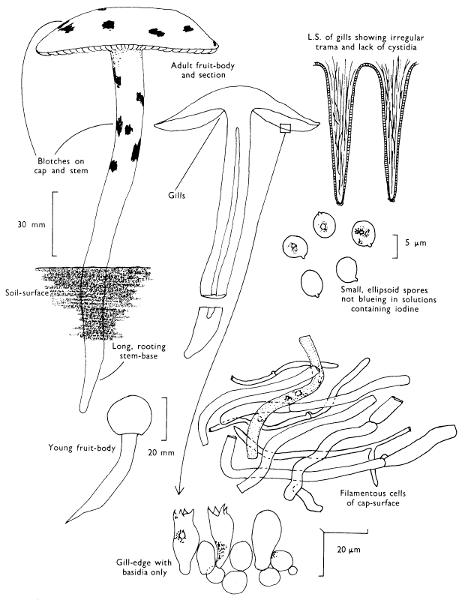

Fig. 1. Dissection of a toadstool as recommended by the author. For explanation see text.

[14]

Material in good condition is always required and one of the first things the student needs to do is train himself to collect sufficient material in good condition. The steps by which all the structures of the fungus used in the text can be observed are outlined below:—

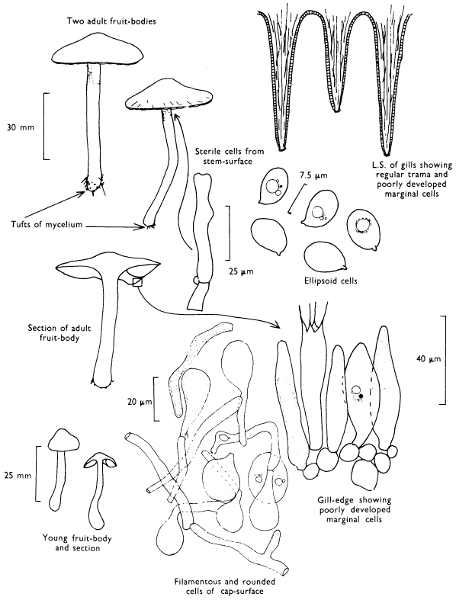

Fig. 1 shows the cuts required to furnish suitable sections in order to observe the various structures and patterns of tissue which are important.

1. Carefully place the longitudinal section (AB) of the fruit-body which has been sketched gill-face down under a low power or dissecting microscope. Hairs or gluten on the cap, if present, will be made visible by focusing up and down (figs. 2 and 3A) and/or those on the stem (fig. 3B). When any part of the cut fruit-body is not being examined retain it in a chamber containing damp paper or moist moss; this will assist the cells to retain their turgidity, for they frequently collapse on drying and are difficult to observe except after performing often lengthy and special techniques.

If only one fruit-body is available, then cut along CD and mount in a tin box on a slide in order to obtain a spore-print (otherwise see paragraph 6).

2. Cut off a complete gill (E) and quickly mount on a dry slide. Under the low power of a microscope, the cystidia on the gill-margin will be visible (fig. 4); it will be seen whether the spores are arranged in a particular pattern (fig. 5) and whether the basidia are 2-spored or 4-spored. In white-spored toadstools it is difficult sometimes to determine whether the basidia are 2- or 4-spored so one must confirm the observations by other techniques.

[15]

[16]

A section of the gill accompanied by a small piece of cap-tissue, as in E, will confirm the presence or absence of noticeable cystidia (or hairs) on the cap. Now mount the section bounded by FG and HI in a drop of water containing either a drop of washing-up liquid and/or glycerine; the soapy liquid helps to expel any water which may tend to cling to the gill-margin amongst the cystidia and the glycerine stops the mount from drying out whilst further sections for comparison are cut and examined. It is at this time that the structure of the outermost layer of the cap can be examined, e.g. whether it is made up of a turf-like structure; the presence or absence of cystidia on the cap can be also confirmed (fig. 7A-C). It is frequently necessary to tap the mount in order to spread the tissue slightly and expose the elements; this can be done very efficiently by light pressure from the end of a pencil to which an eraser is attached. Cut off along line JK to eliminate marginal cystidia from confusing the picture and mount both pieces separately.

3. Cut out a wedge of tissue from the fruit-body (L) so as to have several gills attached to some cap-tissue; until one is familiar with the variability of facial and marginal cystidia, carefully cut along the line PQ (note: the cut is made one-third of the distance from the cap margin, thus eliminating the possibility of large numbers of marginal cystidia being examined in error for facial cystidia). Now make a second cut along the line of RS so that finally a small block of tissue remains (M).

Mount on a dry slide with the plane through PQ face down on the slide and observe under a low magnification, to assess whether cystidia on the gill-face are present or absent, and if present their general shape and whether numerous or infrequent (fig. 8).

Mount in water/washing-up mixture as outlined above and tap gently with the rubber attached to the end of a pencil; evenly distributed pressure should be given. If the gills appear to be too close then rotate the rubber a little whilst pressing in order to spread the tissue.

4. Using a low power of a microscope and looking down into the plane RS of the unmodified block M or a similar block, one obtains by this simple technique a very accurate idea as to the structure of the trama of the gill (fig. 9). The organisation of this tissue is very important in classification, some groups of toadstools having what has been described as regular trama (fig. 9C), others irregular (fig. 9D), inverse (fig. 9B) or divergent (fig. 9A). This same tissue may be thick or sparse to wanting, coloured or not. Such sections are often better than attempts at very thin sections unless very specialised techniques are used. There are few satisfactory thicknesses between the two extremes; the thick sections you can do and the very thin requiring expert techniques.

5. Take out a small block of tissue T as indicated in the figure (fig. 1). Mount immediately and repeat as in 3. This will allow the outer layer of the cap to be more clearly seen (fig. 7A-C) and also the structure of the flesh (fig. 10). The latter may be composed of a mixture of filaments and ‘packets’ or ‘nests’ of rounded cells (i.e. heteromerous), or of filaments, only some of which may be inflated (i.e. homoiomerous); but when individual cells are swollen they never form distinct groups. By very similar techniques it is possible to show that the more woody fungi can have flesh composed of one of four types of cells (Corner, 1932): these types depend on whether distinctly thickened cells (plate 47) are present with the actively growing hyphae or not (pp. 140-150), whether hyphae are present which bind groups of hyphae together, etc. (plate 46).

6. Remove stem along line CD and cut out small blocks of tissue as indicated (U, V and W). Mount immediately and examine as in paragraph 3, for cystidia, etc. (see fig. 3).

Whilst all these sections are being cut and processed a second fruit-body, if available, should be set to drop spores; this is done by cutting off the cap from the stem and placing it either entirely or in part, and with gill-edges down, on a slide in a tin.

7. Z is a ‘scalp’ of a cap; a thin sliver from the cap is placed on a slide in a drop of water (modified with washing-up liquid, etc. as above). After placing a cover-slip over the tissue it is tapped gently; this will show if the cap is composed of globose to elliptic elements or if it is composed of strictly filamentous units (figs. 6A & B). Care must be taken not to reverse the section when transferring it to the mountant, either by turning the scalpel or by allowing the surface tension of the liquid to pull the section upside down. The construction of any veil fragments will also be seen in this mount, and if a loose covering of veil is present this should be removed before observation so that it does not obscure the fundamental structures.

8. Examine the stipe of the fruit-body used above under a low power or with a dissecting microscope in order to ascertain whether there are any remains of veil and/or vegetative mycelium. If found, mount immediately in the solution containing iodine mentioned above and examine.

[19]

Of course it is difficult to carry out the above system the first time and be successful in seeing everything, indeed in being able to cut all the sections 1-8. Practice makes perfect, so why not practise with a 1⁄4 lb of mushrooms from the grocer before the autumn season starts. In this way you will have overcome the difficulties without having to experiment with your collections.

[20]

| CHARACTERISTICS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF HIGHER FUNGI WITH CAPS | |||||

| Locality | G. Ref. | Date | |||

| Habitat notes | soil type | pH | |||

| vegetational community | |||||

| solitary; in troops or rings | |||||

| Draw or preferably paint exterior and vertical section of fruit-body | |||||

| MACROSCOPIC CHARACTERS | |||||

| CAP | |||||

| General characters: | |||||

| diameter | shape | consistency | |||

| colour: | when immature | when mature | |||

| when wet | when dry | ||||

| Surface | |||||

| dry, moist, greasy, viscid, glutinous, peeling easily or not, smooth, matt, polished, irregularly roughened, downy, velvety, scaly, shaggy |

|||||

| Margin | |||||

| regular, wavy | incurved or not | ||||

| smooth, rough, furrowed | striate or not | ||||

| Veil, if present | |||||

| colour | abundance or scarcity | ||||

| distribution at margin, whether appendiculate or dentate | |||||

| consistency, whether filamentous, membranous | |||||

| GILLS, or pores or teeth etc. | |||||

| remote, free, adnate, adnexed, emarginate, subdecurrent, decurrent | |||||

| crowded or distant | distinctly formed or not | ||||

| shape | interveined or not | ||||

| easily separable from the cap-tissue or not | |||||

| consistency (whether brittle, pliable, fleshy or waxy) | |||||

| thickness | width | ||||

| colour: | when immature | at maturity | |||

| number of different lengths or number of layers | |||||

| obvious features of gill-edge, tube-edge, e.g. colour, consistency | |||||

| STEM | |||||

| central, eccentric or lacking | shape | ||||

| dimensions: length | thickness | ||||

| hollow or not | |||||

| colour: | when immature | when mature | |||

| consistency (whether fleshy, stringy, cartilaginous, leathery or woody) | |||||

| surface characters (whether fibrillose, dry, viscid, scaly or smooth) | |||||

| characters of stem-base | |||||

| Veil, if present | characters | ||||

| Volva, if present | characters | ||||

| Ring, if present | |||||

| whether single or double | whether membranous or filamentous | ||||

| whether persistent, fugacious or mobile | whether thick or thin | ||||

| whether apical, median or basal | |||||

| FLESH | |||||

| colour in cap: | when wet | when dry | |||

| colour in stem: | when wet | when dry | |||

| colour changes if any when exposed to air | |||||

| presence or absence of milk-like or coloured fluid | |||||

| (note: colour when exuded on fruit-body immediately and after some time and when dabbed on to a clean cloth or paper handkerchief and exposed to the air). | |||||

| SMELL | before and after cutting | —relate to a common every day odour | |||

| MICROSCOPIC CHARACTERS | |||||

| BASIDIOSPORES | |||||

| colour in mass | colour under microscope. | ||||

| shape | size | type of ornamentation, if any | |||

| size and shape of germ-pore, if present | |||||

| iodine reaction of spore-mass:—blue-black to dark violet (amyloid); red-purple | |||||

| (dextrinoid); yellow-brown or brown (non-amyloid) | |||||

| BASIDIA | number of sterigmata | ||||

| CAP-FLESH | type of constituent cells | ||||

| GILL-TISSUE | type and arrangement of cells between adjacent hymenial faces | ||||

| CAP-SURFACE | type of cells composing the outermost layer—whether filaments or rounded cells | ||||

| STERILE CELLS—CYSTIDIA | |||||

| presence or absence of sterile cells:— | |||||

| on gill-edge | on gill-margin | ||||

| on cap | on stem | ||||

| shape, estimation of size, thick or thin-walled, hyaline or not | |||||

| types of ornamentation, etc. | |||||

[21]

[22]

[27]

Cap: width 45-150 mm. Stem: length 70-200 mm; width 20-30 mm.

Description: Plate 1.

Cap: convex and becoming only slightly expanded at maturity, pale brown, tan or buff, soft, surface dry, but in wet weather becoming quite tacky, smooth or streaky-wrinkled and cap-margin not overhanging the tubes.

Stem: white, buff or greyish, roughened by scurfy scales which are minute, pale and arranged in irregular lines at the stem-apex, and enlarged and dark brown to blackish towards the base.

Tubes: depressed about the stem, white becoming yellowish brown at maturity, with small, white pores which become buff at maturity and bruise distinctly yellow-brown or pale pinkish brown when touched.

Flesh: watery, very soft in the cap lacking distinctive smell and either not changing on exposure to the air or only faintly becoming pinkish or pale peach-colour.

Spore-print: brown with flush of pinkish brown when freshly prepared.

Spores: very long, spindle-shaped, smooth, pale honey-coloured under the microscope and more than 14 µm in length (14-20 µm long × 5-6 µm broad).

Marginal cystidia: numerous and flask-shaped. Facial cystidia: sparse, similar to marginal cystidia.

Habitat & Distribution: Found in copses and woods containing birch trees, or even accompanying solitary birches.

General Information: This fungus is recognised by the pale brown cap, the white, unchanging or hardly changing flesh and the cap-margin not overhanging the tubes. There are several closely related fungi which also grow with birch trees but they need some experience in order to distinguish them. This fungus was formerly placed in the[28] genus Boletus, indeed it will be found in many books under this name. Species of Leccinum are edible and considered delicacies in continental Europe. The majority can be separated from the other fleshy fungi with pores beneath the cap, i.e. boletes, by the black to brown scaly stem and rather long, elongate spores. The scales on the stem give rise to the common name ‘Rough stalks’ which is applied to this whole group of fungi.

Illustrations: F 39C; Hvass 253; LH 122; NB 1556; WD 891.

Cap: width 30-100 mm. Stem: width 15-20 mm; length 50-70 mm.

Description: Plate 2.

Cap: convex or umbonate at first, later expanding and then becoming plano-convex, golden-yellow or rich orange-brown, very slimy because of the presence of a pale yellow sticky fluid.

Stem: apex reddish and dotted or ornamented with a fine network, cream-coloured about the centre because of the presence of a ring which soon collapses, ultimately appearing only as a pale yellow zone; below the ring the stem is yellowish or rusty brown, particularly when roughly handled.

Tubes: adnate to decurrent, deep yellow but becoming flushed wine-coloured on exposure to the air, with angular and small sulphur-yellow pores which become pale pinkish brown to lilaceous or pale wine-coloured when handled.

Flesh: with no distinctive smell, pale yellow immediately flushing lilaceous when exposed to the air, but finally becoming dingy red-brown, sometimes blue or green in the stem-base.

Spore-print: brown with distinct yellowish tint when freshly prepared.

Spores: long, ellipsoid, smooth and pale honey when under the microscope, less than 12 µm in length (8-11 µm long × 3-4 µm broad).

Marginal cystidia: in bundles and encrusted with amorphous brown, oily material. Facial cystidia: similar in shape and morphology to marginal cystidia.

Habitat & Distribution: Found on the ground accompanying larch trees either singly or more often in rings or troops.

General Information: This fungus is easily recognised by the poorly developed ring, overall golden-yellow colour and pale yellow viscidness on the cap which comes off on to the fingers when the fruit-body is handled. There are several closely related fungi which also grow with coniferous trees, e.g. Suillus luteus Fries, ‘Slippery jack’, but many need experience in order to identify them. All these fungi were formerly placed in the genus Boletus, because of the fleshy fruit-body with pores beneath the cap. The larch-bolete receives its common name from the close relationship of the fungus with the larch. On drying S. luteus and S. grevillei may strongly resemble one another but the former can be distinguished when fresh by the chocolate brown, sepia, or purplish brown cap and the large whitish, lilac-tinted ring.

[29]

[30]

[31]

Species of Suillus are edible and rank highly in continental cook-books, although they have disagreeably gelatinous-slimy caps, a character, in fact, which helps to separate them from other fleshy pore-fungi.

Illustrations: F 41a; Hvass 257; ML 187; NB 1044; WD 842.

Cap: width 70-130 mm. Stem: width 34-37 mm; length 110-125 mm. (36-40 mm at base).

Description: Plate 3.

Cap: hemispherical, minutely velvety, but soon becoming smooth and distinctly viscid in wet weather, red-brown flushed with date-brown and darkening even more with age and in moist weather to become bay-brown.

Stem: similarly coloured to the cap but paler particularly at the apex, smooth or with faint, longitudinal furrows which are often powdered with minute, dark brown dots.

Tubes: adnate or depressed about the stem, lemon-yellow but immediately blue-green when exposed to the air and with angular, rather large similarly coloured, pores which equally rapidly turn blue-green when touched.

Flesh: strongly smelling earthy, pale yellow but becoming pinkish in centre of the cap, and blue in the stem and above the tubes when exposed to the air, but finally becoming dirty yellow throughout.

Spore-print: brown with a distinct olivaceous flush.

Spores: long, spindle-shaped, smooth, honey-coloured under the microscope and greater than 12 µm in length (13-15 µm long × 5 µm broad).

[32]

Marginal cystidia: numerous, flask-shaped and slightly yellowish.

Facial cystidia: scattered and infrequent and similar to marginal cystidia in shape.

Habitat & Distribution: Found in woods, especially accompanying pine trees, but often found fruiting on the site of former coniferous trees, even years after the trunks or the stumps have been removed.

General Information: This fungus is recognised by the rounded, red-brown cap, coupled with the pale yellow flesh and greenish yellow tubes, both of which become greenish blue when exposed to the air. There are several species in the genus Boletus which stain blue at the slightest touch or when the flesh is exposed to the air, e.g. B. erythropus (Fries) Secretan, a common bolete with a dark olivaceous cap, orange pores and red-dotted stem.

The flesh of some species of Boletus, e.g. B. edulis Fries, however, remains unchanged or at most becomes flushed slightly pinkish. Although many people say they recognise B. edulis, the ‘Penny-bun’ bolete—a name derived from the colour of the cap, there is some doubt as to whether the true B. edulis is common in Britain as we are led to believe. B. edulis and its relatives are highly recommended as edible (see p. 35). B. badius is also edible, but it is ill-advised to eat any bolete which turns blue when cut open.

Illustrations: B. badius—F 38c; Hvass 248 (not very good); LH 191; NB 1095; WD 851. B. edulis: F 42a; Hvass 246; LH 191; NB 1433.

There are nearly seventy boletes recorded for the British Isles and evidence of others which have as yet not been fully documented. As a group they are characterised by being fleshy, possessing a central stem and producing their spores within the tubes, and not on gills as in the common mushroom. It is the first character by which the boletes differ so markedly from the other pored fungi, such as the ‘Scaly Polypore’ (see p. 140).

The boletes have long been classified in the genus Boletus, but instead of referring all the pored, fleshy fungi to a single large genus several genera are now recognised. The separation of these genera is based on differences in colour of the spore-print and differences in the anatomy of the tubes, cap and stem, etc., e.g. members of the genus Suillus have colourless or pale coloured dots on the stem exuding a resin-like liquid in wet weather, which is clear and glistening in some species but turbid and whitish in others, gradually darkening and hardening so that the stem is ultimately covered in dark brown or reddish smears or spots; members of the genus Leccinum on the other hand never exude liquid and have coarse or fine roughenings on the stem which are usually dark, but may commence white and ultimately darken depending on the species; many species of Boletus possess a very distinct raised network all over the stem, whilst others have it present only in part, or have minute, often brightly coloured, dots replacing it.

[33]

[34]

Within this single, yet not particularly large, group of fungi, several biological phenomena are demonstrable. There is good evidence that the majority of British boletes are mycorrhizal; several species are known to be associated only with one species of tree or group of closely related tree-species. Thus Suillus grevillei and S. aeruginascens (Secretan) Singer grow in association with larch trees; S. luteus and Boletus badius in contrast grow in association with pine trees; Leccinum scabrum with birch trees; L. aurantiacum (Fries) S. F. Gray, with poplar trees and L. quercinum (Pilát) Green & Watling, with oak trees.

Boletus edulis can be separated into several distinct subspecies which are associated with different trees; the two commonest subspecies are those associated with birch and with beech trees. It is well known that although present in this country during the warmer periods of the Ice-Age, larch neither survived the intense cold of the last advance of the ice nor migrated back into Britain after the ice had melted. Thus all larches which we see in Britain have been planted by man. There is little doubt that mycelia of many fungi were introduced along with these plants very probably including the mycelium of the larch-bolete. A similar pattern can be seen with other introduced trees, although not to such a marked degree, e.g. spruce trees. The beech tree, however, is native to the south of England, unlike the larch returning to this country after the ice had melted; it has been planted extensively outside its former range in northern areas of the British Isles taking with it its associated fungi. There is some evidence that some stocks of beech and fungi have been introduced from continental Europe in comparatively recent times.

A parallel, yet inexplicable association is found between the bolete Suillus bovinus (Fries) O. Kuntze and its close relative Gomphidius[35] roseus (Fries) Karsten where the mycelium of two fungi are found intertwined forming a close association! Parasitism although rare is also found amongst the boletes, and an uncommon parasitism at that—a fungus on a fungus; for example in Britain although infrequent Boletus parasiticus Fries grows attached and ultimately replaces the spore-tissue of the common earth-ball (Scleroderma, see p. 192).

Those fungi which grow on dead and decaying substrates are called saprophytes and although the greater number of higher fungi would be included in this class of organisms the character is infrequent amongst the boletes. One British example of this type of fungus is the rare Boletus sphaerocephalus Barla which grows on woody debris.

Chemists have long been interested in boletes, for as noted above the flesh of some species when exposed to the atmosphere turns vivid colours, a feature often incorporated into the Latin name, e.g. Boletus purpureus Persoon, from the purple colours produced whenever the fruit-body is handled. The reaction appears to be an oxidation where in the presence of an enzyme and oxygen a pigmented substance or substances are produced. What the significance of these colour-changes is in nature is as yet unknown; however, what is interesting is that many of the chemicals involved are unique and have only recently been analysed completely; they are related to the quinones.

There is little doubt that it is this rapid and intense blueing of the flesh of many boletes that has lead to a belief that they are poisonous. It is uncertain whether there are any truly toxic species of Boletus but several have unpleasant smells and tastes which make them very unattractive. Boletus edulis is the important ingredient, however, which gives the distinctive taste to so-called dried mushroom soup. Thousands of fruit-bodies are collected annually in the forests of Europe to be later dried and processed for incorporation into soup. Boletes appear to form an important part of the diet of several rodents and deer and in Scandinavia in the diet of reindeer.

Probably one of the most obscure of our British boletes is Strobilomyces floccopus (Fries) Karsten, the ‘Old Man of the Woods’. It has a black, white and grey woolly, scaly cap and stem, and the flesh distinctly reddens when exposed to the air. The spores are almost spherical, purple-black in colour and covered in a coarse network when seen under the microscope. All these characters readily separate Strobilomyces from all other European boletes; however, in Australasia, members of this and related genera form a very important part of the flora.

[36]

Cap: width 30-150 mm. Stem: width 10-18 mm; length 60-120 mm.

Description:

Cap: convex with a pronounced often sharp umbo, wine-coloured, flushed with bronze-colour at centre and yellow or ochre at margin, viscid but soon drying and then becoming paler and quite shiny.

Stem: yellowish orange, apricot-coloured or peach-coloured, streaked with dull wine-colour, spindle-shaped or narrowed gradually to the apex from a more or less pointed base.

Gills: arcuate-decurrent, distant, at first greyish sepia then dingy purplish with paler margin, but finally entirely dark purplish brown.

Flesh: lacking distinctive smell and reddish yellow or pale tan in the cap, rich apricot- or peach-colour towards the stem-base.

Spore-print: purplish black.

Spores: very long, spindle-shaped, smooth, olivaceous purple and greater than 20 µm in length (20-23 × 6-7 µm).

Marginal cystidia: cylindrical to lance-shaped and up to 100 × 15 µm.

Facial cystidia: similar to marginal cystidia.

Habitat & Distribution: Found in pine woods, usually solitary or in small groups. Fairly common throughout the British Isles and characteristic of Scots Pine woods.

General Information: This fungus can be distinguished by the purplish or wine-coloured cap and the gills being pigmented from youth. There is only one other British species of this genus, i.e. C. corallinus Miller & Watling.

Chroogomphus is separated from Gomphidius by the flesh having an intense blue-black reaction when placed in solutions containing iodine, and the gills being coloured from their youth. In many books Chroogomphus is placed in synonymy with the genus Gomphidius. However, Gomphidius glutinosus (Fries) Fries, G. roseus (Fries) Karsten and G. maculatus Fries all have whitish gills when immature which gradually darken, and their flesh simply turns orange-brown in solutions of iodine. G. glutinosus is uniformly grey in colour and is most frequently found under spruce and other introduced conifers: G. roseus has a pale-pinkish coloured cap and white stem, and grows with pine; G. maculatus grows under larch and is flushed lilaceous at first but becomes strongly spotted with brown when handled.

Illustrations: Hvass 192; LH 213; WD 833.

[37]

[38]

Cap: width 50-120 mm. Stem: width 8-15 mm; height 30-75 mm.

Description:

Cap: at first convex with a strongly inrolled, downy margin, but then expanded and later frequently depressed towards the centre, clay-coloured, ochre or yellow-rust, slightly velvety but becoming smooth or sticky particularly in wet weather and readily bruising red-brown when fresh.

Stem: central or slightly eccentric, thickened upwards, fibrillose-silky, similarly coloured to the cap but typically streaked with red-brown particularly with age.

Gills: ochre or yellow-brown then rust and finally darker brown, decurrent, crowded, often branched and united about the apex of the stem; easily peeled from the flesh with the fingers and rapidly becoming red-brown on handling.

Flesh: thick, soft and with slightly astringent smell and yellowish to brownish but becoming red-brown after exposure to the air.

Spore-print: rust-brown.

Spores: medium-sized, ellipsoid, smooth, deep yellow-brown and rarely greater than 10 µm in length (8-10 × 5-6 µm).

Marginal cystidia: numerous lance-shaped or spindle-shaped.

Facial cystidia: scattered and similar in shape to marginal cystidia.

Habitat & Distribution: Found on heaths and in mixed woods, particularly where birch has or is now growing, or even accompanying solitary birch trees.

General Information: This fungus is easily recognisable by the strongly inrolled, woolly margin of the cap and yellow-brown gills which are easily separable from the cap-flesh. P. rubicundulus P. D. Orton is similar but grows under alder and has yellow gills unchanging when handled and dark scales on the cap. P. atrotomentosus (Fries) Fries and P. panuoides (Fries) Fries both grow on coniferous wood and have smaller spores; the former is recognised by the dark brown to almost black shaggy stem and the latter by the shell-shaped cap devoid almost completely of a stem.

Illustrations: F 41c; Hvass 189; LH 185; NB 1158; WD 702.

[39]

[40]

Cap: width 60-125 mm. Stem: width 15-25 mm; length up to 180 mm.

Description:

Cap: bell-shaped or bluntly conical only slightly expanding with maturity, smooth or wrinkled at centre but often furrowed at the margin, slimy, brown with a distinct olive flush when in fresh condition and becoming ochraceous brown and shiny when dry.

Stem: usually swollen to some degree about the middle, slimy particularly towards the base, whitish throughout when young except for a faint amethyst or violaceous flush in the lower part; as the slime dries the stem becomes shiny and the outer surface breaks up into fibrillose scales or scaly, irregular ring-zones.

Flesh: lacking distinct smell, white with ochraceous flush in the cap, white in the stem, thick and soft in the cap but fibrous in the stem.

Gills: adnate, broad, rather thick, frequently veined and distant, ochraceous brown and finally deep rust-brown.

Spore-print: rust-colour.

Spores: long, slightly almond-shaped in side view, finely warted throughout and not less than 12 µm in length (13-14 × 7-8 µm).

Marginal cystidia: ellipsoid or club-shaped, hardly different from the surrounding undeveloped basidia.

Facial cystidia: absent.

Habitat & Distribution: Found on the ground in copses and woods especially those containing beech.

General Information: Recognised by the conical, grooved cap and the slimy spindle-shaped stem with a distinct violaceous flush; this fungus is often misnamed C. elatior Fries but this is a much less common fungus. There are several closely related fungi, but these grow with other tree-species and need much more experience to distinguish one from the other. C. pinicola P. D. Orton is one such species growing in the litter under Pinus sylvestris, Scots Pine; this species is fairly common in the remnant pine woods of Northern Scotland. The large size, sticky or glutinous cap and stem indicate that this fungus belongs to Cortinarius, subgenus Myxacium.

Illustrations: Hvass 145; LH 162; NB 119; WD 601.

[41]

[42]

The genus Cortinarius is the largest genus of agarics in the British Isles, indeed in Europe and North America—perhaps in the world. It includes some of our most beautiful agarics, yet it is one of the least satisfying to the mycologist because of the difficulties experienced in identifying collections—partly because many species are so seldom seen.

Cortinarius contains just under two hundred and fifty recognisable British species, although recent research has shown that many more are yet to be described from this country as new to science. Except for some very characteristic species the individual members within the genus Cortinarius are often very difficult to separate one from the other; however, Cortinarius is one of our least difficult genera to recognise in the field owing to the presence when mature of rust-coloured gills and a cobwebby veil which extends from the margin of the cap to the stem. This structure is termed a cortina (Fig. 14) and in young specimens covers the gills with delicate filaments. As the cap expands the cottony or cobwebby filaments are stretched and either disappear entirely or may collapse to form a ring-like zone of filaments on the stem. In some species a second completely enveloping veil is also found, and this veil is viscid in one distinct group of which C. pseudosalor already described is a member. The gills in the genus are variable in colour when young although constant for a single species; they may be lilaceous purple, orange, brown, red, yellow-ochraceous or tan, but ultimately in all members at maturity they become rust-colour. The spores under the microscope are richly coloured, yellow to red-brown and are frequently strongly warted; in mass they are rust-brown and this character coupled with the presence of the cobweb-like veil characterises the genus.

Within the genus Cortinarius there is a wide range of characters varying from species with distinctly sticky caps and stems, some with sticky caps and dry stems to those with both dry caps and stems. A few species are very large and fleshy whilst others are quite slender and many of the latter rapidly change colour on drying out and are then said to be hygrophanous. However, although there is such a large spectrum of characters in a single genus the species all have in common the cortina and rust-coloured gills, the latter often appearing as if powdered with rusty dust.

[43]

Utilising the characters mentioned above this very large genus can be split into the following six sections, called by the mycologist subgenera:

In several continental books some or all of these divisions are recognised as distinct genera in their own right. The subgenus Telamonia which occurs in many texts was formerly thought to differ from Hydrocybe in the presence of a universal veil; the universal veil is a second veil which completely envelopes the fruit-body when it is young and is in addition to the cortina. However, the modern treatment would seem to suggest that the presence of the universal veil is not of the utmost importance and so the two subgenera are incorporated into one. The name Hydrocybe reflects the character of changing colour as it dries out because of the loss of water. Within each subgenus the species are distinguished by the colour of the young gills and of the cap, the veil colour and texture, and microscopic characters of the spores, particularly their size.

The majority of species of Cortinarius are mycorrhizal and like the boletes possess very specific relationships with tree species. Thus some are typical of coniferous woodland and others typical of deciduous woodland in general, whilst others typify woods of a particular tree, e.g. beech, oak, birch, pine, larch. Some species are characteristic of woods on limestone or chalky soils (calcareous) whilst others are characteristic of woods on sandy, heathy acidic soils. For example, Cortinarius armillatus (Fries) Fries which is found in damp woods and possesses one or more cinnabar-red or scarlet zones on the stem and[44] red fibrils at the stem-base appears to be connected with birch. Several species are associated with native trees whilst others have undoubtedly been introduced from abroad. They are very important in the economy of the woodland ecosystem.

One of the most beautiful and easily distinguished of our British species is Cortinarius violaceus (Fries) Fries which has uniformly deep violet-coloured stem and cap and coloured cystidia on the gill-margin, a character unusual in Cortinarius.

No species are known to be truly poisonous and many species are known to be edible, but many are too small to be of any value. Some of the larger species are regarded as good to eat, but frequently are too scarce. Thus the necessity for experience to recognise the different species, coupled with their often unpleasant tastes make them an unimportant group of agarics for eating.

[45]

Cap: width 50-100 mm. Stem: width 20-35 mm; length 50-100 mm.

Description: Plate 7.

Cap: yellow-ochre or dull yellow becoming paler with age, or flushed faintly greyish green, convex but soon expanding and becoming flat or depressed in the centre, smooth, or granular when young and slightly tacky in wet weather, faintly striate at the margin.

Stem: white at first then flushed slightly greyish, smooth or wrinkled, firm at first but quickly becoming soft and fragile.

Flesh: brittle, firm at first then soft, white, yellow under cap-centre.

Gills: white at first then flushed pale cream-colour, brittle, adnexed to free, rather distant.

Spore-print: faintly cream when freshly prepared.

Spores: medium-sized, hyaline, broadly ellipsoid or subglobose to almost globose, coarsely ornamented with prominent warts which stain blue-black when mounted in solutions containing iodine and which are faintly interconnected by low ridges, about 8 × 7 µm in size (9-10 × 7-8 µm).

Marginal cystidia: prominent, lance- to spindle-shaped and often filled with oily material.

Facial cystidia: similar in shape to marginal cystidia and projecting some distance from the gill-face.

Habitat & Distribution: Commonly found in mixed woods from summer until late autumn.

General Information: Easily recognised by the ochre-yellow cap, very pale cream-coloured spore-print and greying stem. Two other yellow-capped species of Russula are commonly found. R. claroflava Grove with yellow spore-print and blackening fruit-body which grows with birches in boggy places, and R. lutea (Fries) S. F. Gray which is much smaller, having a cap up to 50 mm and very deep egg-yellow gills and spore-print; it grows in deciduous woods.

Illustrations: F 22a; Hvass 226; LH 119; NB 1371; WD 491.

A large genus with nearly one hundred distinct species in the British Isles and several others yet unrecognised or undocumented. This genus is composed generally of large toadstools often beautifully coloured, indeed the majority have brightly coloured caps in reds, purples,[46] yellows or greens depending on the species although a few are predominantly white bruising reddish brown or grey to some degree.

Such large and distinctive fungi one would think would be the easiest members of our flora to identify, unfortunately they are not. They form a group quite isolated in their relations, the only close relatives being members of the genus Lactarius, to be dealt with later (see p. 50). The flesh of members of both Lactarius and Russula contains groups of rounded cells, a feature unique amongst agarics and explains why in Russula the fruit-bodies, cap and gills and sometimes the stem are brittle and easily break if crushed between the fingers. The fruit-body does not exude a milky liquid when the flesh is broken.

The spore-print varies, depending on the species involved, from white to deep ochre and individual spores are covered in a coarse ornamentation which is composed of isolated warts or warts interconnected by raised lines, or mixtures of both. The ornamentation stains deep blue-black when the spores are mounted in solutions containing iodine and the pattern which is produced appears in many cases to be of a specific character.

The majority of the species, if not all north-temperate species are mycorrhizal and the familiar host-tree fungus relationship can be recognised:—

R. claroflava Grove, with birch in boggy places, R. emetica (Fries) S. F. Gray with pine in wet places, R. betularum Hora with birch in grassy copses and R. sardonia Fries with pines. Brief notes are here included giving the basic characters of eight common species, but it must be appreciated the identification of many species within this genus is difficult.

Cap: width 50-100 mm. Stem: width 14-25 mm; length 60-80 mm.

Cap: deep reddish purple but becoming spotted with either cream-colour or white blotches.

Stem: white but becoming flushed greyish or stained brownish with age.

Gills: white then very pale yellow.

Flesh: white in cap and stem.

Spore-print: white.

On the ground in mixed woods and copses, particularly those containing oak.

[47]

[48]

Cap: width 50-150 mm. Stem: width 10-30 mm; length 50-100 mm.

Cap: lilac, bluish to purple often with green tints.

Stem: pure white.

Gills: pure white.

Flesh: white.

Spore-print: white.

Common in deciduous woods, especially beech-woods.

Cap: width 50-100 mm. Stem: width 8-15 mm; length 25-70 mm.

Cap: bright scarlet fading with age to become spotted pinkish, slightly viscid when moist.

Stem: spongy, fragile.

Flesh: white.

Gills: pure white.

Spore-print: pure white.

In pine woods usually in boggy areas.

Cap: width 40-75 mm. Stem: width 10-20 mm; length 30-75 mm.

Cap: tacky when fresh, straw-coloured or pale tawny brown.

Stem: similarly coloured to the cap.

Gills and flesh: pale straw-colour and smelling of House Geraniums (i.e. Pelargoniums).

Spore-print: cream-coloured.

Common under beech.

Cap: width 70-170 mm. Stem: width 15-30 mm; length 50-90 mm.

Cap: slimy, dingy yellow to tawny, margin strongly furrowed and ornamented with raised bumps.

Stem: whitish then flushed or spotted with rust-brown.

Gills: straw-coloured, often spotted brown with age and beaded with watery droplets when growing under moist conditions.

Flesh: white to cream, brittle and with foetid-oily smell.

Spore-print: pale cream-colour.

Common in deciduous woods.

[49]

Cap: width 30-75 mm. Stem: width 7-15 mm; length 35-70 mm.

Cap: scarlet red but developing creamy areas with age, dry.

Stem and gills: white but with a distinct although faint greenish grey flush, the former fairly firm.

Flesh: white.

Spore-print: pure white.

Commonly accompanying beech, even individual trees in gardens.

Cap: width 75-200 mm. Stem: width 15-35 mm; length 25-75 mm.

Cap: cream-coloured then flushed sooty brown, finally black as if scorched by proximity to bonfire.

Stem: white then dark brown.

Gills: pale ochre reddening when bruised, thick and very distant.

Flesh: white slowly dull red on cutting then brown and finally changing soot-colour after some time.

Spore-print: white.

Common in deciduous woods.

Cap: width 50-140 mm. Stem: width 15-30 mm; length 40-60 mm.

Cap: deep blood-red or brownish red.

Stem: white with a flush of red towards the base.

Gills: cream then ochraceous.

Flesh: white staining brownish and smelling strongly of fish- or crab-paste, and staining dark green when a crystal of green iron sulphate is rubbed into it.

Spore-print: deep cream-colour.

Common in mixed woods; a very variable fungus with many colour-forms, but easily recognised by the green reaction with ferrous sulphate.

[50]

Cap: width 60-200 mm. Stem: width 10-25 mm; length 40-75 mm.

Description:

Cap: firm, convex usually with a central depression at maturity, dark olive-brown or dark greyish olive with a yellow-tawny, woolly margin when young which soon disappears, and the whole cap becomes sticky with age and turns deep purple when a drop of household ammonia is placed on it.

Stem: short, stout, similarly coloured to the cap except for the distinctly ochraceous apex, slimy and pitted.

Gills: crowded, cream-coloured to pale straw-coloured, but soon spotted with dirty brown, particularly when bruised.

Flesh: white or greyish ochre exuding a milk-like liquid which lacks a distinct smell and is white and unchanging when exposed to the air.

Spore-print: pale pinkish buff.

Spores: subglobose or ellipsoid and covered in a network of strongly developed, raised lines interconnected by finer ones, both of which stain blue-black in solutions containing iodine, generally 8 × 6 µm in size (7-8 × 6-7 µm).

Marginal cystidia: lance- or spindle-shaped and filled with oily contents.

Facial cystidia: similar to marginal cystidia.

Habitat & Distribution: Common in woods and copses, or on heaths especially in boggy places but always where birch is growing.

General Information: Easily recognised by the dull colours and purple reaction with alkali; there is no British species with which L. turpis can be mistaken. The purple reaction is similar to that found in the familiar school laboratory reagent litmus, for the compound found in L. turpis turns purple in alkali and reddens in acidic solutions. First discovered by Harley in 1893 this reaction marked the beginning of a whole series of chemical studies on the agarics which has led to the discovery of many unique compounds.

Illustrations: Hvass 214 (but too green); LH 213; NB 1133; WD 381.

There is little doubt that the genus Russula and the genus Lactarius are closely related; in fact they stand aside from the other agarics in the very important character mentioned on page 46. In Europe the easiest distinction between the two genera is that members of the genus Lactarius exude a milk-like juice which may be white or variously coloured depending on the species involved (e.g. purple in L. uvidus (Fries) Fries, yellow in L. chrysorheus Fries). The cap, stem and frequently the gills are brittle and when broken liberate the milk-like liquid; when the fruit-body is dry, however, the presence of this liquid may be difficult to demonstrate. The spores have a blue-black ornamentation under the microscope when mounted in iodine, and although when in mass the colours are not as varied as those found in the genus Russula there is every likelihood that they will play an important role in the classification of the group in the future. The colour of the spore-print has been rather neglected, although the genus includes some rather unusual fungi.

[51]

[52]

The odours of many species are very distinct and vary from the smell of coconut and spice to those of various flowers; an odour commonly met with is termed ‘oily rancid resembling butter which has become mouldy’; in early books it was described as being the smell of bed-bugs!

The majority of the species are undoubtedly mycorrhizal: thus L. torminosus is found with birch, L. deliciosus and L. rufus with conifers and L. quietus with oak. Brief notes are given on additional species:—

Cap: width 20-50 mm. Stem: length 20-50 mm; width 4-6 mm.

Cap and stem: red-brown.

Gills: reddish brown.

Flesh: reddish buff with an aromatic odour resembling spices which becomes very strong when dried and exudes a pale thin milk-like liquid.

Common in conifer woods and plantations.

Cap: width 50-120 mm. Stem: length 20-60 mm; width 15-25 mm.

Cap: viscid, dirty greyish ochre with flush of tawny but soon becoming greenish with age.

Stem: dirty buff or greyish ochre, spotted with green particularly with age or on handling.

Gills: orange-yellow bruising deep orange but becoming green with time.

[53]

Flesh: pinkish to apricot-coloured but becoming green with age and exuding a rich orange-red fluid which gradually becomes greyish green.

Frequent in conifer woods and plantations.

Cap: width 20-50 mm. Stem: length 30-50 mm; width 5-8 mm.

Cap: usually with a central ‘bump’, greyish lilac, dull and minutely scaly or velvety.

Stem: white to pale yellowish.

Gills: pale yellowish to flesh-coloured then flushed lilaceous.

Flesh: pale yellowish or flushed lilaceous, smelling strongly of desiccated coconut and exuding a white unchanging milk-like liquid.

In woods and on heaths, particularly where birch is growing.

Cap: width 30-80 mm. Stem: length 40-80 mm; width 10-15 mm.

Cap and stem: milky cocoa-coloured, zoned with reddish brown.

Gills: pale ochraceous then flushed red-brown.

Flesh: similar to gills, smelling strongly of rancid oil, and exuding a white, thin milk-like liquid which becomes very, very faintly yellow on exposure to the air.

Common wherever oak is growing.

Cap: width 50-90 mm. Stem: length 50-90 mm; width 10-15 mm.

Cap: dark red-brown with a distinct, usually sharp ‘bump’ in centre.

Stem: pale red-brown throughout or whitish at base.

Gills: pale reddish brown and exuding a white, unchanging milk-like fluid.

In pine woods and less frequently with birches on acid heaths.

Cap: width 40-150 mm. Stem: length 60-100 mm; width 15-30 mm.

Cap: pale strawberry-pink or pale salmon colour, distinctly zoned, slimy when wet at centre and strongly shaggy fibrillose at margin.

Stem and gills: pale strawberry colour.

Flesh: tinged salmon-pink and exuding a white unchangeable milk-like liquid.

Frequent where birches grow.

[54]

Cap: width 100-175 mm. Stem: width 30-40 mm; length 150-275 mm.

Description:

Cap: bright scarlet to orange-red with scattered whitish or yellowish fragments of veil particularly towards the centre and hanging down from the margin, viscid when moist, striate at margin with age.

Stem: white, striate above the soft easily torn, although prominent, ring which is white above and yellow below; stem-base swollen and ornamented with patches of yellowish or white veil-fragments which form concentric rings or ridges of tissue.

Gills: white, free, crowded, fairly thick, minutely toothed at their edge.

Flesh: soft, lacking distinctive smell, or at times slightly earthy and white, yellowish below cap-centre.

Spore-print: white.

Spores: long, hyaline under the microscope, ellipsoid, smooth about 10 × 7 µm in size (10-13 × 7-8 µm).

Marginal cystidia: composed of chains of swollen, hyaline cells.

Facial cystidia: absent.

Habitat & Distribution: Found in birch-woods, less frequently collected in the vicinity of conifers; wide-spread and fairly common, but it is erratic in its appearance giving the impression of being absent from a locality until one season it suddenly fruits in profusion.

General Information: An easily recognised fungus because of its striking colour. It is also very familiar and well-known because it appears so often on Christmas cards, and features commonly in illustrations in children’s story-books. The fungus contains a poison which formerly was used to kill flies—hence the common name of ‘Fly agaric’ and the scientific name from the latin name for the house-fly. The red skin of the cap, where the major amount of the poison resides, was cut up with a little milk and sugar or honey; flies attracted to this sweet concoction inadvertently ate the poison and later perished. This fungus has a very well documented and long history and appears in the legends of many countries. It is featured in Greek mythology, Slavic and Scandinavian folk-lore and indeed appears in the pre-history of Indian tribes of N.E. Asia. It has even been connected with the formation of certain sects within the early Christian church.

Illustrations: F. frontispiece; Hvass 1; LH 117; NB 1131; WD 21.

[55]

[56]

The genus Amanita contains many important mycorrhizal fungi including the ‘Blusher’, A. rubescens (Fries) S. F. Gray, the ‘Tawny grisette’, A. fulva Secretan, and the ‘False death-cap’, A. citrina S. F. Gray. The first grows on heaths and in woods with a variety of trees; A. fulva frequently grows with birch and A. citrina with several leafy trees although its var. alba (Gillet) E. J. Gilbert appears to be confined to beech woods. However, there is some evidence that many members of the genus in drier more southern countries than Britain, are non-mycorrhizal. In fact the genus as a whole may be southern-temperate in its distribution. In the British Isles the number of species of Amanita recorded decreases as one goes north, or the frequency of single species except for a few widespread forms falls off northwards. In a few cases a more familiar southern species is replaced in similar habitats by another species, e.g. A. phalloides (Fries) Secretan is replaced by A. virosa Secretan the ‘Destroying angel’ in Scotland, and A. citrina frequently in the north by A. porphyria (Fries) Secretan. Species of Amanita are usually large conspicuous fungi and the genus contains some of our best known agarics. One, A. muscaria (Fries) Hooker has already been mentioned, but the genus also includes the ‘Death-cap’ A. phalloides and ‘Caesar’s mushroom’ A. caesarea (Fries) Schweinitz, a fungus not found in this country but considered to be superior in edibility to all other fungi; thus edible and deadly poisonous species are found closely related and this simply emphasises how important it is not to eat the agarics one finds in the woods and fields except when accompanied by a ‘real’ expert. Deaths or near fatalities in Europe and North America are recorded annually due to the eating of fungi belonging to this genus.

The poisonous qualities of the fungi in this genus—only a very small amount of poison is often sufficient to produce fatal results—has led to a close connection between these fungi and black magic and the supernatural. This connection is even more emphasised when it is learnt that some have an intoxicating effect. Hence the long history mentioned earlier.

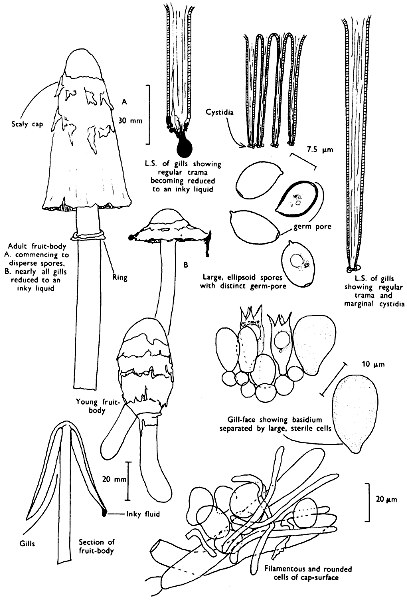

Members of the genus Amanita are characterised by their anatomy and certain macroscopic features; the former is illustrated under A. muscaria, i.e. the divergent gill-trama. The main macroscopic character of note is the presence of a volva at the base of the stem[57] and it is the details of this volva which helps to distinguish different species. A. phalloides has a distinct, loose, membranous sheath, in A. citrina the volva is reduced to a narrow rim around the bulbous stem and in A. rubescens and A. muscaria the volva is simply a series of concentric zones of woolly scales. All the four species noted above possess a ring, but A. fulva the ‘Tawny grisette’ and A. vaginata (Fries) Vittadini the ‘Grisette’ only possess a volva; this has lead to the use of the generic name Amanitopsis in many books, now no longer considered necessary.

The veil in Amanita is probably the most highly developed amongst our common agarics and from Appendix iv it can be seen how the scaly cap and stem originate and how the volva differs from the ring. The volva and cap-scales constitute what has been called the universal veil and the ring which stretches from the cap margin to the stem has been termed the partial veil.

The spores of species of Amanita are large and their shape and chemical reactions help to distinguish the different species within the genus. One of the most interesting features, however, is that the spore-mass, although usually described as white, in many species is not white but flushed greenish grey, etc. The slight subtleties in colour of the spore-print assist in classification.

The following notes may be instructive in conjunction with the information above (for common names see above).

Cap: width 55-80 mm. Stem: width 18-22 mm; length 70-80 mm.

A lemon-yellow or whitish capped agaric with bulbous stem-base, white patches of volva on cap and white stem with flesh strongly smelling of new potatoes.

Spores: almost globose and measuring 9-10 × 7-8 µm.

Cap: width 75-140 mm. Stem: width 20-28 mm; length 85-120 mm.

A greyish or brownish capped agaric with clavate stem-base, grey patches of volva on the cap and white concentrically scaly stem with flesh unchanged on exposure to the air.

Spores: broadly ellipsoid and measuring 9-10 × 8-9 µm.

[58]

Cap: width 70-120 mm. Stem: width 12-25 mm; length 65-100 mm.

A reddish fawn or pinkish buff capped agaric with swollen stem-base, pinkish or flesh-coloured patches of volva on cap and reddish concentrically scaly stem with flesh becoming reddish when exposed to the air.

Spores: ellipsoid and measuring 9-10 × 5-6 µm.

Cap: width 48-95 mm. Stem: width 12-20 mm; length 65-100 mm.

An olive-brown or smoky brown capped agaric with only slightly swollen stem-base, white patches of volva on the cap and white concentrically scaly stem with unchanging flesh.

Spores: ellipsoid and measuring 8-12 × 7 µm.

Cap: width 70-85 mm. Stem: width 12-20 mm; length 85-120 mm.

A greenish or yellow-olive capped agaric with stem sheathed in membranous volva, white patches of volva on cap and smooth, white stem with white flesh.

Spores: broadly ellipsoid and measuring 10-12 × 7 µm.

Cap: width 40-60 mm. Stem: width 10-15 mm; length 100-150 mm.

A thin, tawny-brown agaric with stem sheathed in membranous volva and pale tawny, slightly scaly stem.

Spores: globose and 10-12 µm in diameter.

Differs from A. fulva in the cap being metallic grey or silvery in colour.

[59]

Cap: width 50-150 mm. Stem: width 10-12 mm; length 75-150 mm.

Description: Plate 10.

Cap: at first convex then more or less flattened or slightly depressed, very variable in colour, yellowish, olive, buff, sand-coloured or some shade of brown, at first covered in small, brownish or ochraceous scales which give the young cap a velvety aspect, but gradually the scales disappear with age except at the cap-centre; margin striate and usually paler than centre of the cap.

Stem: equal or swollen at base, often several grouped together, white at apex above a whitish, rather thick, ring which is flushed with olive-yellow or red-brown at its margin; stem-base fibrillose, whitish but finally red-brown at maturity.

Gills: adnate or slightly decurrent, whitish then flushed flesh colour and developing brownish spots with age or in cold, wet weather.

Flesh: with rather strong and unpleasant smell, white or flushed pinkish in the cap, brown and stringy in the stem.

Spore-print: very pale cream colour.

Spores: medium-sized, hyaline, ellipsoid, less than 10 µm in length (8-9 × 5-6 µm).

Marginal cystidia: variable, hyaline, cylindric and not well-differentiated.

Facial cystidia: absent.

Habitat & Distribution: This fungus grows in troops or is found joined at the base to form clusters. It is always attached to old trees, trunks, stumps and buried wood, either directly or by its vegetative stage which darkens and aggregates to form strands resembling boot-laces which are called rhizomorphs.

General Information: This rather variable, and therefore often perplexing, fungus causes a destructive rot of trees and can travel long distances through the soil with the use of its rhizomorphs. It commonly grows on several species of broad-leaved trees, but can also colonise conifer trees. It also attacks garden shrubs, such as privet-hedges, and is particularly destructive to Rhododendrons causing a wilt of the whole shrub and subsequent death; it has also been recorded as attacking potatoes. The actively growing mycelium which can often be found growing under the bark of infected trees, exhibits a luminosity[60] if freshly exposed and placed in a darkened room. The rhizomorphs of A. mellea are highly specialised structures composed of mycelial threads some of which have become rather more differentiated than is normally found in the vegetative stage of other agarics.

Illustrations: F 27a; Hvass 26; LH 93; NB 1411; WD 43.

Cap: width 50-120 mm. Stem: width 17-25 mm; length 95-125 mm.

Description: Plate 11.

Cap: convex, but expanding and becoming flattened with a slight central umbo, ochre-yellow to yellowish rust-colour and covered with dark brown recurved scales which are particularly dense at the centre.

Stem: variable in length and thickness depending on how it is attached to the substrate, whether in a deep crack or wound, or in a depression, and how many specimens are in the cluster; its colour is similar to that of the cap, exhibits a small, dark brown fibrillose, torn ring or ring-zone and is ornamented with recurved red-brown scales below that ring.

Gills: broadly adnate with a decurrent tooth and crowded, yellowish at first then rust-coloured.

Flesh: with strong, pleasant but pungent smell, yellowish brown, soft in the cap, fibrous in the stem.

Spore-print: rich rust-brown.