The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Forest Monster, by Charles E. LaSalle

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Forest Monster

or, Lamora, the Maid of the Canon

Author: Charles E. LaSalle

Release Date: March 29, 2019 [EBook #59147]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FOREST MONSTER ***

Produced by Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(Northern Illinois University Digital Library at

http://digital.lib.niu.edu/)

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

Chapter I. The Mysterious Rescue.

Chapter III. Teddy O’Doherty’s Encounters.

Chapter IV. The Demon at the Camp-fire.

Chapter VI. Black Tom’s Adventure.

Chapter IX. “I Had a Dream Which Was Not All a Dream.”

Chapter X. The Wonderful Cavern.

Chapter XI. Around the Camp-fire.

Chapter XII. Hunting Wealth by Firelight.

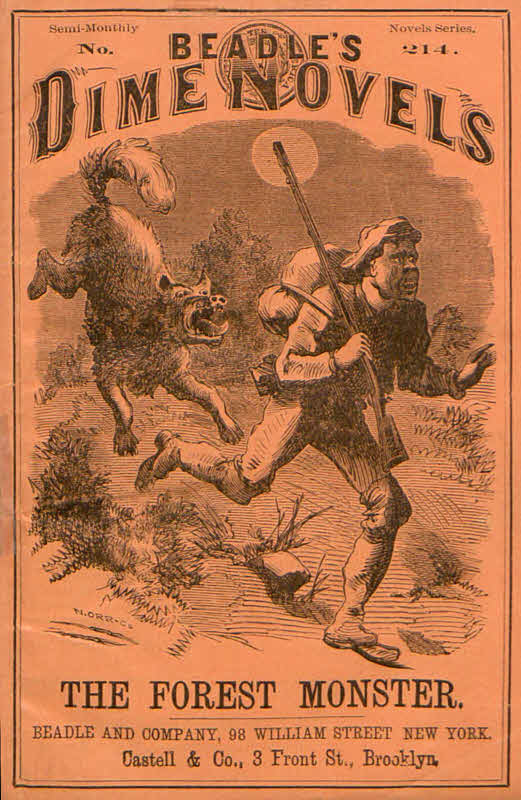

Semi-Monthly Novels Series.

No. 214.

BEADLE’S

Dime novels

THE FOREST MONSTER.

BEADLE AND COMPANY, 98 WILLIAM STREET NEW YORK.

Castell & Co., 3 Front St., Brooklyn.

ROMANCE OF THE WOODS AND LAKES!

A most charming story of wildwood life is

Beadle’s Dime Novels, No. 215,

TO ISSUE TUESDAY, OCTOBER 25,

introducing a favorite writer in a favorite field, viz.:

THE WHITE HERMIT:

OR,

The Unknown Foe.

A ROMANCE OF THE LAKES AND WOODS.

BY W. J. HAMILTON,

Author of “The Giant Chief,” “The Silent Slayer,” etc.

The interest which centers around the early years of settlement, when what is now the lovely region of Central New York was a wilderness of woods, streams, lakes, cataracts and rugged hills, is perennial; and in the fierce Iroquois, the dreaded Six Nations, the half savage white ranger, the colonial trooper, the resolute settler, the true forest women, the romance writer finds almost exhaustless material for the construction of his historic stories. Of the writers in this field of fiction Mr. Hamilton is well known as a master. He gives such pictures of forest life, such clear-cut portraits of forest men, as render his creations intensely interesting and attractive.

This last work of his hand is one of impressive merit, and will greatly delight the lovers of forest romances.

☞ For sale by all Newsdealers and Booksellers; or sent, post-paid, to any address, on receipt of price—Ten Cents.

BEADLE AND COMPANY, Publishers,

98 William Street, New York.

A ROMANCE OF THE FAR WEST.

BY CHAS. E. LASALLE,

Author of “Burt Bunker, Trapper,” “The Green Ranger,”

“Buffalo Trapper,” etc.

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND COMPANY, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1870, by

BEADLE AND COMPANY,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

(No. 214.)

THE

FOREST MONSTER.

The wind was howling over the prairie, with a sharp, penetrating power, while a few feathery flashes eddying through the air, showed that although it was the season of spring, yet in this elevated region of the Far West, there was scarcely the first premonition of its breath.

The night was closing in, and the vast peaks of the Black Hills, that had loomed up white and grand in the distance, were gradually fading from view until they merged into the thickly gathering gloom, while the blasts that whirled the snow in blinding drifts about their tops, came moaning and sweeping over the bleak prairie, as if searching for some one to inclose in its icy grasp, and to strangle out of life.

Now and then the desolate howl of the mountain wolf, came borne on the wind, adding to the gloomy desolation of the scene, while the dark, swarming multitude of buffaloes hurried over the frozen ground, as if fearful of being caught in the chilling blast. It was a bad night to be lost upon the prairie.

Is there no one abroad to-night?

From the grove of hardy cottonwood yonder, a starlike point of light suddenly flashes out upon the night. Surely that is the light of some hunter’s camp-fire.

A party of emigrants have halted for the night, and this is the first camp-fire that has been started, for it is not only cold, but there is cooking to be done, and a fire is indispensable.

The emigrant party numbers some twenty men, a half-dozen women, and about double that number of children. They are on their way to Oregon, and have penetrated thus[10] far without encountering any obstacle worth noting, although for days they had been journeying through the very heart of the Indian country.

Among the party was a man named Fred Hammond, who had joined it more for the purpose of adventure than any thing else. He was mounted on a magnificent black horse, was an amateur hunter, and a general favorite with the company.

Among the latter was not a single experienced mountaineer or prairie-man. They had secured the service of an old man, who professed to be thoroughly acquainted with the overland route to Oregon, but there was more than one who suspected his knowledge and believed he was nothing but a fraud.

Extremely good fortune had attended them thus far. They had caught sight of numerous parties of Indians, and indeed scarcely a day passed without something being seen of them. They had exchanged shots at quite a distance, but no harm had befallen the whites, and they had penetrated thus far on their way to distant Oregon.

But Hammond and one or two of the members were filled with misgiving. Through the day they had seen evidence of an immense Indian party being in their vicinity, and they feared the worst. It was with pain that they saw the huge camp-fire kindled, and Hammond called his comrade, Beers, to one side, and said, in his earnest voice:

“I tell you, things look darker than ever before.”

“So I think.”

“I believe we are followed by over a thousand Indians, and they intend attacking us to-night.”

“What shall we do?”

“God only knows; I don’t like that camp-fire.”

“Let it burn for a short time; they don’t need it long, and then it can be allowed to die out.”

“But it will betray our position.”

“Do you suppose there is any means possible by which we can conceal it?”

“Not entirely, but partly.”

As the night deepened it became of intense darkness. There was no moon, and the sky was entirely overcast with[11] clouds, so that there was scarcely any light at all. The few flakes of snow that were whirling through the air had entirely ceased, but the wind still whistled through the grove.

“There is a moon up there,” said Hammond, “and if the clouds break away at all, we shall have enough light to guide us on our way.”

On account of the danger, which all knew threatened them, a number proposed that as soon as their animals had had sufficient rest, they should move out of the timber and continue their journey; but this was finally overruled, as they were not only likely to go astray in the darkness, but the Indians could easily find them, from the unavoidable noise made by their wagons.

If attacked on the open prairie at night, they were entirely at the mercy of their assailants, who could easily encircle and tomahawk and shoot them all, while in the grove they could make a fight with some prospect of success.

So it was prudently determined to remain where they were.

In the course of an hour, when there was no imperative necessity for a fire, it was allowed to slumber and finally die out. The wagons were placed in a rude circle, with the animals within, while the women and children, and such men as were relieved from duty, sought their quarters for the night, and soon silence rested upon all.

A double guard was set. Ten men were scattered around the outer edge of the globe at regular distances from each other, on the alert for the first indications of danger.

Beers and Hammond stood next to each other, and the former finally left his station and took his position beside the latter.

“What’s the use?” he muttered, by way of apology. “When it’s so dark that you can’t see any thing, where’s the good of straining your eyes? As we have got to depend on our sense of hearing, we’ll help each other.”

The air was so sharp and keen that they had great difficulty in keeping themselves comfortable. They dare not stamp their feet or swing their arms, and such movements as they made, were made with a stealth and caution that nearly robbed them of all their virtue.

At the end of an hour the sky gave some signs of clearing. It was somewhat lighter overhead, but still the earth below was little benefited thereby. There was scarcely any variations in the wind, although several fancied that it had somewhat decreased.

Another hour passed drearily away, and then Beers suddenly laid his hand on the arm of Hammond.

“What is it?”

“Hark!”

Borne to them on the wind came the distant but distinct sound of a horse’s feet, as he galloped over the hard prairie.

The rapid clamp of the hoofs were heard for an instant, and then the varying wind swept the sound away from their ears, and all was still.

But in a moment they rallied out again with startling distinctness—then grew fainter—died away and rung out once more.

“Some one is riding fast,” said Beers.

“And he is coming this way,” added Hammond.

A few minutes convinced them of the truth. A single horseman was riding at great speed over the prairie, and was manifestly aiming straight for the grove where the emigrants had halted for the night.

As a matter of course, all the sentinels had observed it by this time, and there was great excitement among them. They gathered about Hammond to receive his directions.

“Go back to your stations,” said he. “Keep your eyes and ears open for others, whether they be mounted or afoot, and I will attend to this one.”

His orders were obeyed, for he was looked upon as having authority in this matter, and with an interest difficult to understand they awaited the coming of the horseman.

As the latter came nearer, he seemed to be heading straight for the point where Hammond and Beers were standing.

During the last few moments, the sky had cleared so rapidly that objects could be distinguished for quite a distance, and the two men strained their eyes through the gloom to catch sight of the stranger.

“There he is,” whispered Hammond, as the dim outlines of a horse was discovered through the darkness.

The horseman had reined his horse down to a walk, and was advancing quite cautiously. He continued onward until within a dozen feet of the two men, when he reined up.

“Who comes there?” asked Hammond.

“A friend.”

“What do you seek?”

“You are in great danger, and I have come to warn you of it.”

“Good heavens!” exclaimed Beers, in an undertone; “that is a woman!”

Hammond had noticed the wondrously soft and musical voice, and he now walked forward, so as to stand beside the horse. The dim light showed that Beers spoke the truth; it was a woman seated upon the horse.

“May I ask your name?”

There was a moment’s hesitation, and then the female answered:

“I am Lamora; and I speak the truth.”

“We do not doubt it,” responded the amazed Hammond. “What is it you have to say?”

“A thousand Blackfeet warriors are coming down on this grove, two or three hours before sunrise, and if you remain, there will not be one who will escape alive.”

“What shall we do?”

“Make ready as soon as possible and start westward. Let there not be a moment’s delay, and you will be saved.”

“But they can follow us to-morrow, (if not to-night,) and attack us by daylight.”

“They can, but they will not,” replied Lamora, with the greatest earnestness. “This is a great war-party on their way southward to fight the Cheyennes. They are to meet a long ways off to-morrow; the Blackfeet have given themselves just enough time to massacre you and your friends, if you remain in this grove, as they expect you will; but if they come here and do not find you, they will have no time to follow up your wagons, and thus, you see, if you improve your time, you will be saved.”

“Beers,” said Hammond, turning to the man beside him, “rouse the men and have this thing done without a moment’s[14] lost time, while I make a few more inquiries of our unknown friend.”

Beers darted away, and almost immediately was detected the rapid moving to and fro, and the bustle of getting ready to start.

“Your orders are being obeyed,” said Hammond, addressing the lady, who still sat her horse beside him.

“It is well that they are,” she replied, with a sigh of relief; “the Blackfeet know that you are encamped here, and they have no reason to think you will not be here when they are ready to strike.”

“Do you know where they are?”

“Over that ridge of hills, several miles to the northward. They have been riding, throwing the tomahawk, and making every preparation for the great battle which is to come off to-morrow between them and the Cheyennes.”

“This, then, is only a diversion?”

“That is it; they naturally think that, as they find you in their way, they may as well indulge in a little preliminary practice.”

“We were fearing an attack, as we knew that there were a large number of Indians in our vicinity, and we heard the sound of your horse’s feet long before we heard you. Being thus warned and prepared, could we not have made a successful defense, with the shelter of these trees, which you probably know are very numerous about us?”

“No,” was the instant answer of Lamora; “if there were no more than a hundred Blackfeet, you might repel them; but a thousand would overwhelm you. There are sounds of preparation upon the part of your friends.”

“Yes; we shall soon be on the move.”

“Keep straight to the westward; there is now enough light to prevent your going astray, and you will find, when daylight comes, that Heaven has brought you out of all danger. Farewell!”

Ere Hammond could interpose, or even thank her, the horse had wheeled about and was off on a gallop. Almost instantly, he vanished in the darkness, and the rattle of his hoofs grew fainter and fainter, until they, too, died out in the distance.

“Lamora,” repeated the young man. “I surely have heard that name pronounced by other lips than hers.

“Who is she? Where did she come from?

“She was sent by heaven, most assuredly.”

While conversing with the girl, Hammond had approached her horse as near as possible, and had managed to gain a distinct view of her face. There is something in the dim, misty moonlight which softens the asperities even of the repulsive countenance, but he was certain that the most beautiful creature upon which he had ever looked was conversing with him. Her half-civilized dress, and her wealth of flowing black hair, partly assisted in her enchanting appearance; but the face itself was one of unsurpassed loveliness.

The peculiar circumstances under which they encountered gave Hammond an equally peculiar interest in her, and a pang of disappointment went through his heart when he found that he was standing alone, and that she had left him so abruptly.

But he had important matters in hand for the time, and he gave his whole thought to them.

Every one was working with the energy of people who were convinced that their lives depended upon the result. The teams were harnessed, the wagons loaded up, and at the end of half an hour the whole train moved out of the grove, toward the west.

Before starting, men had ridden out on the prairie in every direction, and returned with the announcement that nothing could be heard of the Blackfeet, and all pressed forward with the greatest vigor and determination.

With the passing of the immediate danger, the thoughts of the strange woman who had befriended them returned to Fred Hammond. He felt a powerful interest in her, and, as he was riding beside the guide of the company, he turned to him rather abruptly, and asked:

“Have you ever heard of Lamora?”

“Heard of her?” repeated the latter, in surprise; “wasn’t I telling you all about her the other day?”

“So you were; I was sure I had heard her name before, but I could not recollect from whom. Who is she?”

“She is a white girl, living with a tribe of Indians, somewhere up north of us, and she has done many such things as[16] this for the white people crossing the plains. I have heard of her for years as doing the same thing.”

“What kind of a looking person is she?”

“Just the handsomest creature that ever lived! Wait till you get a good look at her.”

Hammond was not long in finding that their guide knew very little more regarding her than he had already told, although he gossiped and chatted about her until daylight.

When light at last broke over the prairie, many eyes were cast anxiously backward, but not a sign of the Indians was visible. The warning of Lamora had saved them!

Fred Hammond could not drive the thoughts of this beautiful being from his mind, and finally he determined that, as he had joined the company for the sake of adventure, he would turn back and seek adventures of the most romantic kind.

So, on the afternoon of this day, he quietly withdrew from the company, and started at an easy gallop in the direction that the guide had indicated led toward the home of the mysterious and beautiful Lamora; and, leaving our hero for a time to himself, we must now bestow our attention upon others, who have a part to play in this narrative. Love, the passion of our nature, will play the mischief with all of us, and Fred Hammond was soon off on this great “love-chase” of his life.

Black Tom and old Stebbins had a hard day’s ride of it, and they drew the rein in a heavily-timbered grove, just as the sun was setting, with the intention of camping there for the night.

They were well up toward the Black Hills, in a country broken with forest, hill and prairie, and interspersed with streams of every size, from the rivulet and foaming cañon to the broad, serenely-flowing river.

They were in a region infested with grizzly bears and the[17] fiercest of wild animals, and above all with the daring and treacherous Blackfeet—those dreaded red-skins of the North-West, with whom the hunters and trappers are compelled to wage unceasing warfare, and who are more feared than any tribe that the white men encounter.

So these veteran prairie-men proceeded with all their caution and kept their senses on the alert for any “sign” of their old enemies, who came down sometimes like the sweep of the whirlwind, and who had the unpleasant trait, after being thoroughly whipped, of not staying whipped.

Dismounting from their ponies, old Stebbins walked back to the edge of the timber, and carefully made a circuit around it. He was thus enabled to gain quite an extended view of the surrounding prairie, although his view was broken and obstructed in several places.

Tired and ravenously hungry as he was, he moved cautiously and made his tour of observation as complete as it was possible to make it. Finally he turned about and joined his companion, who had kindled a good roaring camp-fire during his absence, and had turned both horses loose to crop their supper among the luxuriant grass and budding undergrowth of the grove.

“Well, Steb., how do you find the horizon?” asked Black Tom, who bore that soubriquet on account of his exceedingly dark complexion.

“Cl’ar, as the sky above?”

“Nary a sign?”

“Yas—thar’s signs, but the sky is powerful cl’ar.”

This apparently contradictory answer requires a little explanation. Old Stebbins had detected signs of Indians—indeed had indubitable evidence that they were in the neighborhood; but the signs which indicated this fact to them indicated still further that the same Indians, or Blackfeet, as they undoubtedly were, had no suspicion of the presence of white men. This, therefore, disclosed a “clear sky” so far as the trappers were directly concerned, although they were thus made aware that there was a dark, threatening cloud low down in the horizon, which might rise, and send forth its deadly lightning.

Looking to the westward, Stebbins saw a wooded ridge a hundred rods or so distant, which shut off any further view in[18] that direction; but, about a half-mile beyond this, his keen eyes detected the smoke of a camp-fire. It was very faintly defined against the clear blue sky, but it was unmistakable, and indicated that a party of Indians were encamped there.

Why, then, did Black Tom sit so unconcernedly upon the ground, after hearing this announcement, and permit their fire to burn so vigorously, when its ascending vapor might make known to the Blackfeet what they did not even suspect?

Because night was closing around them, and ere the red-skins would be likely to detect the suspicious sign, it would be concealed in the gathering darkness—and the dense shrubbery effectually shut out the blaze from any wanderers that might venture that way.

As there was nothing at hand immediately to engage their attention, the trappers, after gathering a goodly quantity of fuel, reclined upon the ground, and leisurely smoked their pipes.

“Teddy is gone a powerful while,” remarked Tom, as he looked up and saw that it was quite dark; “he can’t be as hungry as we are.”

“He’s seed the sign—and he’s keerful—hello!”

At that instant, the report of a gun was heard, sounding nearly in the direction of the Indian encampment. The trappers listened a moment, and then Tom added, in the most indifferent manner possible:

“Wonder ef that chap’s got throwed.”

“Hope not,” returned his companion, “fur ef he is we’ll have to go to bed on an empty stomach, or scratch out, and hunt up our supper for ourselves.”

The individual who had occasioned this remark was Teddy O’Doherty, a rattling, jovial Irishman, who had got lost from an emigrant train several years before, and in wandering over the prairie fell into the hands of the trappers, with whom he had consorted ever since.

He had spent enough time among the beaver-runs of the north-west, to become quite an expert hunter; he had acquired a certain degree of caution in his movements, but there still remained a great deal of the rollicking, daredevil nature, which was born in him, and he had already been engaged in several desperate scrimmages with the red-skins, and the wonder was that he had escaped death so long.

Like a true Irishman, he dearly loved a row, and undoubtedly he frequently “pitched into” a party of Indians, out of a hankering for it, when prudence told him to keep a respectable distance between him and his foes.

On this afternoon, when riding forward over the prairie, old Stebbins indicated to him the grove where they proposed spending the night, when the Irishman instantly demanded:

“And what is it yees are a-gwine to make yer sooper upon?”

“We’ll have to hunt up something,” replied Tom; “we’re out of ven’son, and thar don’t seem to be any fish handy.”

“Do yees go ahead, and make yerselves aisy,” instantly added Teddy. “I’ll make a sarcuit around the hill yonder, jist as I used to sarcle around Bridget O’Moghlogoh’s cabin, when I went a-coortin’, to decide whether to go down the chimney or through the pig-stye in the parlor. Do yees rest aisy, I say, and I’ll bring the sooper to yees.”

And with this merry good-by, he struck his wearied pony into a gallop, and speedily disappeared over the ridge to which reference has been already made, and the trappers passed on to the grove, where we must spend a few minutes with them, before following the fortunes of the Irishman, who speedily dove, head foremost, into the most singular and astounding adventure of his life.

The hunters listened some time for a return-shot or shout to the gun, but none was heard.

“It was Teddy’s bull-dog,” said old Stebbins. “I know the sound of that critter, for I’ve fired it often ’nough.”

“Wal, thar hain’t been any answer to it, as I guess it was p’inted at some animile instead of red-skin.”

This seemed to be the conclusion of both, as they gave no further thought to the absent member of their party.

It was a mild day in late summer, before the vegetation had given any indication of the approaching cold season. The hunters had ventured thus early into the trapping-grounds for two reasons: one was to mislead the Blackfeet, who would be looking for their coming a month or two later, and the other reason will become apparent hereafter.

“To-morrow we’ll strike the trapping-grounds,” said old Stebbins, in his careless manner, as he lazily whiffed his pipe.

“It’s two months yet afore we need set our traps,” said Black Tom.

“That’ll give us plenty of time to find out all we want to,” replied his companion.

“Yas,” added the other, somewhat significantly; “we’ll l’arn whether thar’ll be any need of our ever settin’ them ag’in or not.”

“Not quite that,” said old Stebbins, with a laugh and shake of the head. “I don’t b’l’eve that.”

“I don’t know,” continued Black Tom, who seemed in the best of spirits; “it looked powerful like it when we had to dig out last spring.”

“It did, summat—”

“B’ars and beavers!” exclaimed Tom, suddenly coming to the upright position, jerking his coonskin hat from his head, and dashing it upon the ground, “don’t you remember, Steb.?”

“Remember what?” demanded his companion, not a little startled at his manner.

“It was right hyar that we see’d that!”

“See’d what?”

“Old Steb., you’re a thunderin’ fool!” replied Tom, with an expression of disgust. “I guess you’re gettin’ childish. I, s’pose, you don’t remember that—that—what shall I call it?—that we see’d near hyar?”

“How did I furget it? How did we all forget it—Teddy, too?”

There was no doubt that Stebbins recalled the creature to which reference had been made. Unquestionably brave as both of these men were, their appearance showed that they were frightened. Their bronzed and scarred faces were pale, and they looked into each other’s eyes in silence, both revolving “terrible thoughts.”

“Right out thar,” said Stebbins, speaking in a terrified whisper, and pointing toward the open prairie, over which they had just ridden; “how was it that we wa’n’t on the look out fur it?”

“Dunno, when we’ve been talkin’ ’bout it all the way. It’s too bad that it should come right hyar—jest near the very spot we’re after.”

“Mebbe it’s gone away,” added Stebbins, speaking not his belief, but his hope.

“It will be a powerful lucky thing for us, if it has.”

As frightened children huddle close together, around the evening fire, at the thought of the dreadful ghost, so these two stern-featured men, whose faces had never blanched when the howls of the myriad red-skins, who were closing around them, sounded in their ears, now instinctively sat closer together, and looked off furtively in the darkness, as if in mortal dread of some coming and appalling monster.

But this sudden exhibition of fear was mostly temporary in its manifestations. As each clutched his trusty rifle, and recalled the terrible weapon of which he was master, their confidence almost, but not entirely, returned.

“If that thing does come,” finally spoke old Stebbins, in his deliberate but emphatic manner, “and I can get the chance, I’m going to put a rifle-ball into it, smash and clean.”

“S’posen it doesn’t hurt it.”

“That’s onpossible.”

“Dunno,” persisted Black Tom, “from what we’ve hearn of it, they say it don’t mind our guns.”

“Ef it can stand a shot from my gun, then thar ain’t no use in talking,” was the response of the old hunter.

“Don’t you mind what Stumpy Sam told us about it?” asked Stebbins, some minutes afterward.

“I didn’t hear what he told you; you see’d him first.”

“It was two years ago, come the middle of trappin’ season, when Sam said he and three other fellers see’d him. It warn’t a great ways from hyar, and they war riding up one side of a ridge, when jist as they reached the top they met the thing, coming up t’other side. They had a good sight of it, and the whole four fired right into it.”

“Wal?”

“It give a sort of a snuff, turned tail toward ’em, and walked away, as though they hadn’t done nothin’ more nor sneeze at it.”

“That’s Sam’s story,” replied Tom. “I allers b’l’eved he told a thunderin’ lie about it, ’cause why, thar ain’t no animile that could stand four rifle-bullets right into his face.”

“That’s what I say,” assented Stebbins. “Sam and the[22] rest of them fellers must have been so scared, (though it wouldn’t do to tell ’em so,) that they didn’t hit the critter at all, and that’s what makes me kinder want to draw bead on it, and see what it’ll do afterward.”

“But I say, Steb., now s’pose you do get a crack at it, and it don’t make no difference at all; what then?”

“Why,” fairly whispered the old hunter, in his shuddering earnestness, “then I’ll know it’s a spook!”

That was a dreaded word, for it touched the tender point in a brave but ignorant man’s character. Strong in the face of real, tangible danger, they were like children before a peril which they could not comprehend.

Both of these hunters had sent their ounce of lead crashing through the heart-strings of the buffalo and grizzly bear, a hundred yards distant, and they were warranted in believing that no living creature could face such “music” and live.

What, then, were they to think of any thing that could bid defiance to their weapons? Was it not natural that they should look upon it as something outside of the world in which they lived—something to be dreaded, as the possessor in itself of a power above and beyond theirs?

They had heard strange stories of a wonderful beast seen by different hunters and trappers, who had visited this portion of the Black Hills. Common report had placed it somewhat further to the north-west, so that when the year before they had caught a glimpse of it, in sight of the very grove where they were then encamped, they had double cause for amazement.

They had placed these marvelous stories and rumors which reached their ears in the same category, that listeners doubtless often placed theirs, and believed they originated from an encounter with some mis-shapen, malformed brute, that was no more to be feared than the ordinary creatures to be looked for in these wilds, at any time and by any one.

But there came a time when they were most completely undeceived. The preceding spring, when they were returning to the States, and they were heavily laden with furs and peltries, they made their halt for the night in the same grove. They were sitting around the fire, somewhat late at night, as Teddy was sound asleep, when they heard a peculiar barking[23] sound, and both stole hastily out to the edge of the timber to see what it meant.

As they did so, they saw IT going leisurely toward the ridge, its head being away, and its side partly toward them. Both the hunters identified it on the instant. It was smaller in size than the grizzly bear, but was unlike any creature that either had ever seen. Its appearance, so far as they could judge, allied very well with what they had heard.

It had an immense head, short, thick legs, that moved somewhat clumsily over the ground, and a long, bushy tail, like a squirrel, that was curled over its back, as is frequently seen with that diminutive creature. But the most striking feature about it was its color.

It was a clear night with a faint moon, so that the hunters could not see clearly, but they distinguished the leopard-like spots and zebra-like stripes, that dotted and encircled every part of its head and legs, and on the impulse of the moment, Black Tom raised his rifle and fired at it. He was pretty certain his bullet struck, but if it actually did, the creature paid not the least heed, but moved away at a leisurely gait, and speedily vanished.

Such is an account of the first encounter with the fearful nondescript, which, once seen, could never be forgotten. Since then they had seen nothing of it, although they heard many marvelous stories of it when they reached the settlements on the border.

A full hour had passed since the report of Teddy’s gun, and old Stebbins and Black Tom were conversing in their hushed way, when they were startled by the sound of rapidly-approaching footsteps, and they had scarcely time to look up, when Teddy dashed up to them, panting and almost breathless.

“What’s the matter?” demanded his friends, grasping their rifles and starting to their feet.

“The divil! the divil! I’ve seen him! I shook hands wid him, and he’s comin’!”

“Where? where?”

“There! there!” replied the appalled Irishman, pointing and glancing toward the prairie. “He’s comin’; he’ll be here in a minit! Blessed Virgin, protect me!”

It will be remembered that upon the appearance of the strange animal, during the preceding spring, one member of the party, (Teddy O’Doherty,) was asleep, and failed to see it.

But he heard enough of it continually. It was described and conjectured upon again and again in his hearing, until he came to look upon it as an old acquaintance; but having never set eyes upon it himself, he attached little credit to these numerous accounts, and supposed it was a bear or something similar.

“A pecoolyer-lookin’ critter, as everybody obsarved when they viewed me; but a critter, fur all that, that nobody need be afeard of.”

So, when a short distance from the camping-ground of his friends, he left them and started in quest of the antelope, he had no thought of the other dreaded creature that had been seen in this region, and that made its home so near at hand.

Passing over the ridge, he found himself in such a heavily-wooded country, that he dismounted and continued his hunt on foot. His horse was thus left but a short distance from the camp, and the Irishman understood well enough that he would not increase the distance.

The sun was low in the horizon, but, looking westward, Teddy caught sight of the faint column of smoke that had arrested the attempt of old Stebbins. He paused a moment and looked earnestly toward it.

“Red naygurs,” he concluded, “and they’ve squatted down rather close, as Bridget used to observe, when she sot on one side the house in Tipperary, and I on t’other. I will go and inthrodooce myself.”

The intervening ground was very favorable for a reconnoissance, and he moved along with little fear of being discovered. It was fully dark when he reached the strange[25] camp, where not a single person was visible; but a few minutes examination showed that a large number of Blackfeet Indians had encamped there, but all had been gone several hours.

A little careful examination of the surrounding ground, by means of a torch, showed further that they had mounted their horses and gone due westward, exactly in the opposite direction from their friends, and the very course they would have desired them to take.

This was a pleasing discovery for Teddy, but he was reminded that he had started out to procure a much-needed supper for himself and friends, and that night had closed around him without his having done so.

But good fortune awaited him. This was a country of bountiful game, and the Blackfeet had evidently been feasting, for they had left behind them such an abundance of buffalo-meat and venison, that Teddy found no difficulty in picking up an all-sufficiency for his friends.

To make the load as convenient, however, as possible, he put his share within, making a hearty and enjoyable supper, and made sure that he had secured to his back all that Stebbins and Black Tom could dispose of, and then he started homeward.

In his explorations around the camp fire, he had given it such a stirring up that it was burning vigorously, and threw quite an extended circle of light though the surrounding gloom.

Teddy was standing by the fire, looking in upon the embers, and reflecting how good he felt after his dinner, when it suddenly occurred to him that he was a fine target for any foe that might be lurking in the vicinity.

The thought had scarcely crossed his mind, when he saw something flickering before his eyes; he heard a whizz, and knew on the instant that an arrow had missed his face by scarce a hand’s breadth.

Instinctively he threw his head back, and then jumped back in the darkness.

“Be the Vargin, but that’s a leetle too close, as me uncle obsarved, when by mistake he shaved off his nose, instead of the mustache on his chin. Begorra; if I kin only get a chance at the spalpeen.”

He understood from what direction the deadly missile had come, although he could not tell how far away the Indian stood that had fired it. The Irishman was now enveloped in the gloom of the woods, and his self confidence returned. The experience which had been his with the veteran prairie-men had taught him to move over the ground with the stealth and silence of the Blackfoot himself, and were he so fortunate as to be approaching his treacherous foe, he was certain there was no danger of his betraying himself.

“I’m moving as silent as a fairy,” he reflected; “it’s a handy thrick fur a chap in my sitooation—bad luck to it!”

In the darkness his foot caught in a projecting root, and the consequence was, Teddy was thrown forward flat upon his face.

“Bad luck to it!” he repeated, as he hastily scrambled to his feet, “hilloa, there! hold on I say!”

He heard a hurried tramp, and in the gloom caught a flitting glance of an Indian speeding rapidly away from him.

“Howld on, ye dirty coward!” called out the irate Teddy, dashing after him, “howld on, I say, or I’ll bate ye, and I’ll bate yees if ye do.”

It is hardly worth while to say that the Irishman’s command was unheeded. The red-skin whisked away, like a flitting phantom, and almost instantly vanished. Teddy pursued him for a short distance, but he was not much of a runner, and his pursuit could not result in any thing but a complete failure.

He was not given time to aim and fire his gun. His “short and decisive campaign” against the Blackfeet was a defeat!

“Bad luck to that rut!” he muttered, as he made his way back to it; “it was all through that!”

He groped around until he discovered the scene of his mishap, when he revenged himself by tearing and ripping the mute offender to pieces.

“It was yees that saved a coward’s life!” he exclaimed, as he finished his self-imposed task, “and yees shall niver do the likes ag’in.”

It may be said that it takes a hungry man to appreciate the same gnawing want in another, and so Teddy almost forgot that he had a couple of friends, something over half a mile distant, who were looking longingly for his coming.

“They kin wait as well as mesilf,” he concluded, when he recalled the fact. “Thrue, I have a sooper within, and be the same towken, their sooper is without—but, then, what’s the difference?”

However, he concluded that, as the night was now quite well advanced, there was no objection to his rejoining the trappers, and so he started forward.

There was a moon above the tree-tops, and where the country was open he had quite a clear view for a distance of several rods; and, as he recollected very well the route taken in his hunt, there was no fear of his losing his way.

As he moved along, he could see the dark line of the ridge outlined against the sky beyond, and he knew that only a short distance on the other side, his comrades were looking for his coming.

Teddy had a pretty correct idea of the gastronomic capacity of his friends, and so he had loaded himself down pretty heavily with the plunder found around the Blackfoot camp-fire. All that he carried was cooked and prepared, ready for eating.

He was scarcely half-way to the ridge, when he became sensible that he had a very heavy load upon his back; and, coming across a large, flat rock, he sat down upon it for a few minutes’ rest.

“Begorra, if the spalpeens ate all of that, it’ll do till they raich the States ag’in. Hilloa, there!”

This exclamation was caused by the sight of a man walking in a direction at right angles to his own, and only a rod or two in advance. He was walking leisurely, like some one who was returning from a wearisome hunt; and, what surprised Teddy, he was certainly a white man, rather young in years.

“Hilloa, I say!” called out the Irishman, again.

The stranger abruptly paused, and looked inquiringly toward him.

“Well, what is it ye want?”

“Who the blazes be yees?”

“I don’t know as that concerns you,” replied the stranger, resuming his walk, and almost immediately disappearing in the darkness.

The exasperated Teddy shouted to him to hold on, calling[28] him a coward, and seeking by every means imaginable to bring him back. Had it not been that he was so heavily loaded, he would have sought to follow and bring him to terms; but the Irishman scarcely had time to rise to his feet, when the man had vanished.

“Jist me luck!” he growled, as he sunk back again to finish his rest. “I once walked siven miles to attind the wake of Micky McMaghaghoghmoghlan, and whin I got there, found he hadn’t died at all; and so, whin I was felicytaterin’ mesilf on a fight wid this impudent spalpeen, he walks away, widout exchanging a crack of the head wid me. Bad luck to him! but I’ll have a muss wid somebody, if it’s wid old Stebbins or Black Tom, and then I’ll be sure to get whopped, which is better nor not fightin’ at all, at all.”

Teddy was about to resume his walk, when a peculiar sound, something like the bark of a dog, caught his ear.

“What the dooce is that?” he exclaimed, staring about him. “Who’s got dogs in this part of the world?”

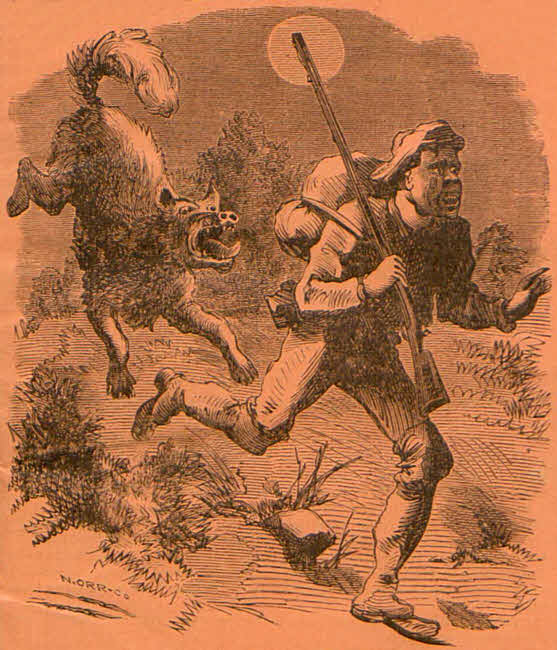

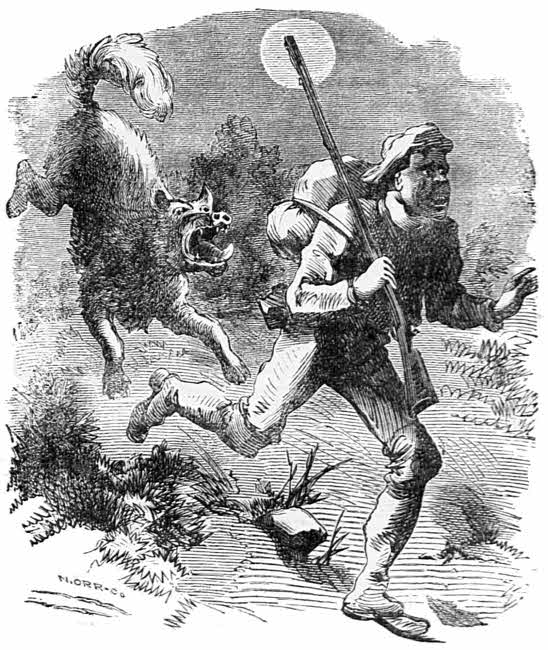

His inquiry was answered by a sight of the creature itself. He saw a large, clumsy-looking animal, with an immense head and a most frightful-looking body, spotted and striped in the most terrible manner, coming straight toward him.

“Begorra! but it’s the divil,” was the Irishman’s conclusion, as he sat like one transfixed, staring at it. “It’s the divil himself, dressed up in his bist soot, and going to the circus.”

It can not be said that Teddy was particularly frightened, for he had his loaded gun in his possession, and with that he was justified in having confidence in his powers of attack and defense.

But suddenly, he recalled the stories he had heard of the strange monster that haunted this portion of the North-West.

“It’s worse nor the divil,” he muttered, “fur it’s that, be the howly Vargin!”

This discovery caused the Irishman some little trepidation, but, at the same time, he was rather pleased that he was about to have an opportunity to try his gun upon it.

Indeed, as the nameless beast continued his leisurely advance, his appearance would have struck terror into the heart of any one. The fantastic, extraordinary hue of its body and legs, the immense tail curved over the back, and its ponderous[29] build, were such that, once seen, no one ever could forget them.

“An’ they say he ates min whole,” thought Teddy, as he silently drew his rifle around in front of him. “His head is big enough, be the powers! Wonder, now, if he isn’t a shark that’s immigrating from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

The fearful brute continued his leisurely advance, as if he saw not, or, at least, cared not for the man who was seated almost in his path. His course was such that, if unchanged for a few seconds longer, would lead him about a rod to one side of the amazed hunter.

The latter, as may well be supposed, scrutinized it most sharply as it approached, and under the dim light of the moon, he had a good opportunity to notice its characteristics.

Its head and body have already been described; its short, dumpy legs very much resembled those of an elephant, while, barring the trunk and tusks, its head was not very dissimilar. It had the same immense palm-leaf like ears; but its mouth looked like that of an alligator—so that its cannibal propensities did not seem so unlikely after all.

It moved heavily and somewhat awkwardly, but its appearance was that of an animal of prodigious strength, much the superior of the famed grizzly bear, and a creature to be shunned in a hand-to-hand encounter.

The idea that would naturally suggest itself upon a glance at this strange creature, would be that it was a cross, combining in itself the characteristics of several animals; but men who had spent years in the West, and understood its native inhabitants thoroughly, declared that such could not be the case. Its build and appearance was unlike any thing that had ever been seen in these parts. It was sin generis, and unlike any thing else.

Some believed that it belonged to an extinct race; probably to the era of the mastodon, and other monsters whose remains are found in the earth; that by some strange providence, it had escaped the destruction of its kind, and still wandered over the world, like a lost sheep, looking in vain for its fold—the last and the least of its race.

But this was a fantastic theory—so utterly impossible, that it deserves no more than simple reference here.

There certainly were some established facts regarding this monster which are utterly unaccountable. It had been fired at again and again, by the most skillful hunters, and yet never gave the slightest evidence of being hurt. Bullets that would have bored their way through the hide of the rhinoceros, and torn on through bone and muscle to the seat of life, seemed to glance aside, as harmless as the tiny hailstones.

There was many a man, certainly, who had tried his weapon upon it, and it still walked the earth to defy their skill and efforts. There were hunters who said they had seen it bite a man in two at one mouthful—just as the alligator or shark serve the swimmer that ventures into their domain.

But while we have drifted into this digression, the situation of Teddy O’Doherty has become more and more critical. He sat with his gun in hand, with his eyes fixed upon the brute, waiting for the opportunity to fire.

He had determined that if it headed straight toward him, he would be polite enough to step aside, for that certainly was not the antagonist to engage in a close fight; but it did not swerve an inch from its path.

And walking thus, it passed about a rod to the left of Teddy, who cautiously raised his gun and took aim.

What better opportunity was possible? It was so close that he could have tossed his hat upon it, and was turned broad-side toward him. If he could stand a shot then, surely he was invulnerable to powder and bullet.

The hunter aimed directly behind the fore leg—that spot which is the vital one to the most dreaded animal, and through which the messenger of death makes his way without challenge. He waited until the foot was thrust forward, and his aim was absolutely certain.

The next instant his piece was discharged.

“Thar! be the Virgin, if that doesn’t fotch yees—”

Heavens! what did he hear and see?

He heard that same bark-like cry that had first caught his ear, and saw the brute coming straight toward him!

Flesh and blood could not stand it; and with a howl of terror, Teddy broke in a run for the camp. A few furious bounds carried him to the bottom of the ridge, when his bad luck overtook him.

Glancing back, he saw the dreadful beast close upon him, galloping along like the cat, when frolicking with its prey. The load upon the back of the fugitive made him somewhat awkward in his movements, and he stumbled and fell flat upon his face. Ere he could rise, his foe was upon him!

Teddy gave up; he believed it was all over with him. Lying flat on his face, he committed himself to heaven, and waited for the beast to devour him.

Ugh! what a galvanic shudder shook him, as he heard its smothered bark repeated, and felt its hideous nose glide along his body! He felt it thrust beneath his breast, and then the beast gave a lunge, like a hog when rooting, as if seeking to turn him over on his back.

“No; be the powers, you don’t,” muttered Teddy. “I’m not the chap that’s goin’ to turn over and see mesilf ate up.”

So, instead of turning, he remained flat upon his face, sliding a few inches over the ground.

With a low growl of rage the monster repeated the attempt, and his victim resisted him as before.

Teddy O’Doherty was brave, almost to fearlessness, but this was too much even for him; and, at that point, he swooned away into unconsciousness.

He probably remained in that condition but a short time. When his senses came back to him, he was lying on his back, with his face upturned to the moon. For a few moments, he was naturally enough bewildered, and he lay motionless until it all came back to him. Then he half whispered.

“I’m dead and ate up! how qu’ar it saams! I never knew it felt this way. Yis, Teddy, you’re ate up!”

Gradually a doubt began to filter through his mind, and he moved his hands about his person to see whether he was all there. His load of provisions were shoved from his back, and[32] lay to one side, while he soon discovered that he was all there and had suffered no physical harm!

Yes; the consciousness finally came to the terrified Irishman that he was still in the land of the living. There was not a wound or scratch upon his person, nor had the food been disturbed, except by the mere act of displacement.

“Begorrah, Teddy O’Doherty, but it’s your own mither’s son that ye be,” he soliloquized, not a little delighted; “but it’s so different that ye feel, that ye’ll have to have somebody to inthrodooce ye to yersilf. I wonder ef that ould craythur is watching fur me.”

The Celt cautiously raised his head and looked about him. There was nothing to be seen of the dreaded beast, look in whatever direction he chose.

“Ef it wasn’t me that wasn’t me, but the baast, then it’s mesilf that would be afther ating Teddy O’Doherty, and be the same towken that I haven’t, I’m sartin the baast isn’t human,” concluded Teddy, as he slowly clambered to his feet and furtively glanced about him.

“Thank the good Lord, and the Vargin, that I’m alive!” he exclaimed, gratefully, as he began picking up his provisions again. “I s’pose the craythur wasn’t hungry, and whin he was pokin’ his nose about me, it’s likely that he was thrying to pick me pockets.”

Filled with wonder at his unaccountable escape from the monster, the Celt begun his walk homeward again. He reached and passed up and over the ridge without discovering any thing of his dreaded enemy. Turning aside, he found his horse quietly grazing where he had left him, and, deeming him as safe there as any where else, he permitted him to remain.

He was now within a short distance of the camp of his friends, and was proceeding in his quiet manner, when a cold thrill ran through him at the sound of that appalling bark.

Turning his head, he saw the beast on a full gallop, coming down the ridge, and scarcely a hundred feet distant.

It was like the explosion of a bombshell behind Teddy, and he broke into a wild run, bounding through the timber and up to the camp-fire with the exclamations that have been recorded.

A horde of mounted Blackfeet, or a dozen grizzly bears, could not have created greater consternation. Old Stebbins and Black Tom, as will be remembered, had been conversing about the mysterious creature, and their minds were full of it.

Instantly they leaped to their feet, and stared out in the gloom.

“Whar is he?” demanded Black Tom.

“Close behint me,” replied the terrified Irishman, running around to the opposite side of the camp-fire.

“I don’t see him—b’ars and bufflers! thar he comes!”

Unconsciously the two trappers took their position side by side. They had stood by each other in many fearful and dangerous scenes, and neither would desert the other at this time.

As Tom spoke, both he and his companion caught sight of the hideous brute, coming through the bushes straight toward them. It was walking quite slowly, and at intervals gave forth that peculiar bark, which had a strange, cavernous sound.

Viewed from the front, its appearance was appalling in the extreme. Its head was of vast size, its mouth in latitude resembled that of the alligator. As it advanced, the firelight shone full in its face, and curiously enough neither of the hunters could discern any thing that resembled eyes, although of course it was sentient.

Very naturally the two trappers had determined to send their messengers into his eyes, satisfied that, if there was nothing superhuman in its make, it could not prove invulnerable to such an attack; but they were unexpectedly deprived of this great advantage, seeing which Black Tom whispered to his companion:

“Aim under the throat, and maybe we’ll reach its heart.”

No more than a dozen feet separated men and beast, when the former simultaneously drew their guns to their shoulders, took a quick but sure aim and fired.

They might as well have buried their bullets in the solid oak beside them, for all the good that was accomplished. That peculiar bark of the brute may have been caused by the sound as well as by the bullet of the gun.

It stood a moment, as if looking steadily at the men, and then resumed its advance.

This was too much, and with a howl of terror the three men scattered and were up the nearest saplings in a twinkling. Here they felt a certain degree of safety, as it was hardly probable that such a constructed creature could “climb a tree.”

“But if he chooses,” replied Teddy, from his perch in reply to this remark, “he kin pull up the tree by its ruts, and crack our heads togither.”

Finding himself master of the situation, the mysterious brute took every thing very quietly. Teddy having fastened the meat to his back, had not removed it upon climbing the tree, so that there was nothing on the ground for it to devour; and the trappers were too veteran hunters to fail to carry their weapons with them.

The camp-fire had just been heaped up with fuel, and was now roaring and crackling furiously. The brute seemed to contemplate it a few minutes in quiet wonderment, and then he sat down upon his haunches like a bear, and looked fixedly at the blaze.

“Look at the spalpeen!” called out Teddy. “Did ye ever see sich impudence. He looks as if he owned the grove and us too.”

“That’s jest ’bout what he does own,” replied Black Tom, with grim humor.

“He reminds mesilf, whin I used to sit down in the pratie patch at home, in Tipperary, and think I owned the whole of it, and so I would, if it hadn’t been that anuther chap claimed it.”

During these few minutes, all three of the men had been reloading their guns, as best they could in their circumscribed position. When ready it was arranged that they should discharge their pieces together, at the head of the monster.

This was done, and incredible as it may seem, without result. Struck it undoubtedly was, for it gave a slight twitch with its head, as a dog will do, when pestered with a fly, but it certainly was no more harmed than it would have been by such an insect.

At so short a distance, with such a plain target, it would have[35] been impossible for the bullets to miss their mark, so that no refuge from the difficulty could be taken in that supposition.

The brute sat motionless a moment, with his gaze upon the burning faggots, and then rising from his sitting position, walked around to the other side of the fire, and took his seat directly under the sapling which was the refuge of Teddy O’Doherty.

“Ye dirthy blaguard, ye needn’t come there,” he growled, as he looked down at him; “ye’re a dirthy dog, as me Bridget used to obsarve, affectionately, when she saw me comin’ in her shanty av Soonday avening.”

“He’s fell in love with you,” remarked Black Tom, who thought he could afford to jest a little, so long as the brute made no active demonstrations against him.

“I guess he’s turned watch-dog,” said Stebbins, “and is going to keep the other spooks away.”

It may be stated that the demonstration which the trappers had just received of the invulnerability of the mysterious creature was complete in every respect. They would have staked any thing and every thing that it could have stood without flinching before a battery of columbiads. Under these circumstances, therefore, they did not deem it wise to waste any more powder in firing upon it.

So they reserved their ammunition, and made themselves as comfortable as possible in their elevated position, waiting until it should take it into its head to depart.

“S’pose he stays here a week or two?” said Stebbins.

“Then we must do the same.”

“Why didn’t we think of the fire?” muttered Black Tom.

“What did yer want to think ’bout that?” asked old Stebbins.

“If he don’t care fur rifle-balls, it’s likely he’s afeard of that. If I had only slammed a lot of fire in his face, he’d left.”

“Better not try it,” returned the elder.

“Why not?”

“’Tain’t noways likely it would have hurt him, and he might have cotched you up and slammed you in the fire.”

This was a fearful supposition, and all three shuddered at the thought of the brute venting his spite in such a manner.

As it was certain that nothing could be done in the way of[36] vanquishing the monster, the question now was as to how long he would remain. While he was present, no one could entertain any idea of descending, and if he should take it into his head to spend several days there, there certainly was reason to fear the most serious consequences.

An hour passed and still the brute sat as motionless as a statue. Being several yards from the camp-fire, its fitful light gave him a most terrible appearance. The trio kept up a pointless conversation for a long time, Teddy gradually withdrawing from it, until he became silent altogether.

No notice was taken of this fact for some time, until suddenly Black Tom became suspicious and called his name. Receiving no response, he exclaimed, to old Stebbins:

“Bufflers and Blackfeet! he’s goin’ to sleep!”

“If he does he’s gone, sure. Wake him up!”

“Teddy! Teddy!” called Tom, “wake up, or you never will.”

“Aoogh! what—”

Too late. The Irishman, in his bewilderment, did not comprehend his perilous position, and making an uneasy movement, lost his hold and fell!

And fell in such a manner that he struck full length upon the back of the frightful brute!

A shudder of horror shook the trappers, as they looked down upon what they regarded the certain death of their comrade, who gave a shriek of terror as he rolled like a log helpless to the ground.

The brute started, uttered his sharp, bark-like cry, and then bolted away and vanished in the darkness, without offering to harm the man who lay helpless at his feet.

“Begorra! but he’s a gintleman, as Micky Dunn obsarved of the man that cracked his crown. That’s the sicind time he’s give me the go-by, and the nixt time he does it we’ll shake hands and swear we’re friends.”

“It beats thunder!” exclaimed old Stebbins, who was now prepared to believe Teddy’s account of his extraordinary meeting with this animal.

“It can’t be that he don’t eat men,” said Black Tom, “for Stumpy Sam said he see’d it chaw up one of their men.”

“I guess he don’t like Irishmen.”

“It’s meself that thinks he does,” retorted Teddy, “for he’s tr’ated me like a gintleman all the way through.”

“Ain’t yer going to climb up ag’in?” asked Tom.

“What’s the use, when it’s more comfortable here, as Micky McFee remarked when he was axed to come out of the gutter.”

The Irishman made no attempt to re-climb the tree, although he looked carefully about in every direction in quest of the dreaded creature.

Some fifteen minutes passed and nothing was seen or heard of their dreaded foe, when the hunters, who were excessively hungry, cautiously descended to the ground again.

The first thing done was to replenish the fire, and they determined that if the brute should reappear, they would try the effect of dashing some of the brands in his face.

The next proceeding was to attack the provisions which Teddy had brought back with him, and with such ravenous appetites, they were not long in “throwing themselves outside” of an immense quantity of food.

By this time night was well advanced, but there was no thought of sleep upon the part of any one, excepting Teddy O’Doherty. He had acted as sentinel the night before, and soon became drowsy and stupid.

As he was entitled to rest, he was permitted to stretch out near the fire, with his blanket gathered about him, when he speedily sunk off into utter unconsciousness.

There was some apprehension regarding the horses, and after a while Tom stole away from the fire into the grove to see whether they had been disturbed. Having cropped their full of the rich herbage they were found asleep, as free from alarm as was the sleeping Teddy O’Doherty.

Added to the terror inspired by the very appearance of the dreaded creature, was that of amazement at the unaccountable manner in which it had acted toward the Irishman. Twice it had had him completely in its power, and yet had not harmed a hair of his head.

Why was this? Was it possible that it had really formed a sort of partiality toward Teddy? Such things have been known among wild animals, but it was hardly possible in this case. What, then, could be the explanation?

These were conundrums which the trappers asked themselves repeatedly, and which as repeatedly they were compelled to “give up.”

The night wore gradually away, but nothing more was seen of the terrible monster. The camp-fire was kept burning brightly, and the hunters listened attentively for sounds that might betray his approach.

Once or twice a faint rustling of the leaves caused them to start and look affrightedly out in the gloom, but they caught no glimpse of the frightful beast. Accustomed as the hunters were to all manner of exposure and deprivation of sleep and rest, they found no difficulty in keeping their senses about them, even when their bodies were not in motion.

It was a relief to them when the gray mist of morning began stealing through the wood, and they saw the light of another day illuminating wood and prairie.

They seemed to feel scarcely any desire for sleep, and Tom aroused Teddy by giving him a vigorous kick.

“Come, git up! that beast is looking for you!”

“Let him look!” replied Teddy, as he roused himself. “As long as he behaves himself so well I’ll be glad to see him.”

There remained enough of the provisions brought by Teddy to make a substantial breakfast, after which the horses were brought up and saddled, and in a short time the trappers were on their way toward the north-west.

They had still a short distance to travel before reaching their destination, and while they are thus engaged we will take occasion to refer to a few matters necessary to a full understanding of the incidents that follow.

As we have intimated in another place, old Stebbins and Black Tom were veteran trappers who had been in the “profession” a goodly number of years. Both men had families in Independence, Missouri; and, as the incidents we are giving are supposed to have occurred fully a score of years ago, it will be seen that they were engaged in a most dangerous business.

But they had grown so accustomed to its hardships and perils, that when they left home in each autumn, they felt scarcely different from the traveling-agent, who starts upon his tour of several weeks. Both were strongly attached to their wives and children, and were free from the rough, careless habits of dissipation that so often distinguish such men.

In the spring preceding the opening of our story, the two trappers and Teddy O’Doherty were returning homeward with a plentiful supply of peltries, having three horses, besides those they rode, laden down with them, and they were in the highest spirits at the success of their winter’s work. Reaching a point a short distance from where we saw them encamped, they halted for the night.

Nothing unusual occurred during the night; but in the morning, when old Stebbins went to a small rivulet near by to drink, he discovered a number of shining particles in the sand, which he instantly recognized as gold. He instituted an examination, and found that in several places it was quite abundant, showing that it would amply repay working. He returned to the camp with the information, when Black Tom came in with confirmatory evidence. Near the spot where his comrade had leaned down to drink, he had accidentally loosened a large, flat stone, which he overturned and found any quantity of the auriferous particles. Putting this and that together, the trio came to the conclusion that they had accidentally struck a “gold mine,” and that with care and industry they could easily make their fortune.

The question was then discussed whether they should remain where they were, and follow up the prize that was so nearly in their grasp. Teddy O’Doherty was strongly in favor of it, but the two hunters had families who would look anxiously for them if they overstaid their time, and they had a load of peltries, very valuable, that made the “bird in the hand,” and they were anxious to dispose of them before returning upon any other undertaking.

So, after a careful consideration of the matter, it was decided to press on toward the States, to dispose of their stock, and then return to prosecute their search for gold. This was done; but the return of the hunters was much delayed by the sickness of a child of old Stebbins, who was not considered out of danger for several months. Finally, however, it recovered entirely, and the three set out upon what was to prove a most eventful journey.

By this time it was late in summer, and would soon be time for trapping operations to begin. But the three came without their pack-horses, fully determined to devote all their energies to the hunting for gold.

There was the one “lion in their path,” the dreaded monster, to which we have made such frequent reference, and which, it will be remembered, was seen by them on their return trip homeward, at the time of the discovery of gold.

Had old Stebbins and Black Tom been single men, it is very doubtful whether the attraction of gold would have been sufficient to lead them into a region that was known to contain such an anomaly; but the prospect of placing their families in easy circumstances for life drew them onward, and thus we find them prosecuting their search for the precious metal in the face of such a hideous monster.

It is not often that a man finds a short and easy road to wealth; and, besides the ever-threatening peril of the beast, they made the unwelcome discovery that there were people in this region ahead of them.

This proved that our friends were not alone in their knowledge of the presence of gold in this secluded part of the world, and it looked no ways improbable that they might encounter serious opposition and trouble from them.

Thus they had the four-legged terror, the Blackfeet, and the[41] unknown white men to encounter before they could hope to go back to the United States with “coffers filled.”

It will be recollected that on the night of Teddy O’Doherty’s first encounter with the brute, he saw and spoke to a strange man that passed near him—a stranger who was on foot, and who refused to pause and make known his identity to him.

The presence of this white man, they believed, indicated the presence of others, and it thus behooved our friends to use the utmost circumspection in their movements. They were scarcely a half day’s journey from their destination, and it lacked yet an hour or two of noon, when they reined up their horses for what they intended should be the long halt.

Here was capital hunting-grounds, and it was only a few miles beyond this where it was better, and where they had spent several years in the business. There were hills and mountains, rivers, streams, cañons, prairies, woods, and the most romantic diversification of land; there were abundant places where they could approach within a dozen feet of a foe, without seeing him.

They knew the ground well, and the wonder was that as gold seemed to be all about them in such abundance, they had never detected the indications of it before.

A secluded place was discovered, where their horses were turned loose to roam free and get themselves in prime condition, while their owners were seeking to put their pockets in the same healthy state.

In a rude, cavern-like structure, made by the jumbling of immense masses of rock together in a remote period of the world, the trappers placed their saddles and luggage, while, carrying their rides and spades, they set out upon a prospecting tour.

“I wonder if that ar’ critter is anywhar ’bout yer,” remarked Black Tom, as they moved away together.

“I don’t,” replied old Stebbins.

“Why not?”

“’Cause yonder he is this very minute.”

As he spoke, the old hunter pointed upward to the top of a cliff, full five hundred feet above them, and several hundred yards distant. There, in full relief against the blue sky, stood[42] the beast, his ungainly body so strangely striped and ringed, and its appearance so singular as to be almost indescribable.

For a minute the three men looked at it in silence, and then Teddy O’Doherty removed his coonskin cap and made a low obeisance.

“What’s that for?” asked Black Tom.

“I s’lute him, jist as the gintry in Tipperary used to s’lute me when they saw me ridin’ by on me own jackass, that belonged to another man. The baast is a gintleman, so long as he uses me in the shtyle of last night.”

“You’d better keep cl’ar of him, so long as you can.”

“I shan’t bother him, nor persoom too much on his good nature.”

“’Sh! thar he goes.”

From his high elevation came the faint sound of his peculiar bark, and then the brute turned about, and was immediately lost to view.

“Thar’s no tellin’ whar he’ll next turn up,” said Stebbins, as the three moved forward again.

“No; and I don’t believe when we meet him again, that we’ll get off so easy as before,” replied Black Tom.

The gold-hunters were now in a sort of deep cañon or rent in the mountain, through which ran a small stream of icy-clear water. It was this same rivulet that had displayed the golden particles to old Stebbins, but it was at a point higher up, before it entered into this wild region, and it was now the intention of the three to follow up the stream for a considerable distance, searching it carefully for the same precious metal that had drawn them hither.

In prospecting thus, it was evident that it was necessary to keep a good look-out; and, as Teddy manifested such an appreciation of the nameless brute, that task was deputized to him, while the others were to scrutinize the bed of the small stream for what had caused them to halt in this place.

For several hours the party made their way up the tiny brook without discovering the first indications of gold; yet, they were not discouraged by the fact, for they knew there was plenty of it in the neighborhood.

They had almost reached the spot where they had seen it a few months before, when Stebbins, who was slightly in[43] advance halted, and snuffed the air with the manner of one who scented something suspicious.

“What is it?” asked Black Tom, failing to understand what it meant.

“We’re near something dead—hello!”

As he spoke, the old hunter pointed to a clump of bushes that surmounted a mass of rocks and gravel, seemingly without any soil to give them existence. From it a huge bird, gorged almost to bursting, laboriously rose a few feet in the air, and floated sluggishly down the cañon, a hundred yards or so, when it landed upon a cliff, at a moderate elevation, and then stepped heavily around, so as to face and watch the men that had disturbed him.

“That’s whar it is,” said Tom, looking toward the bushes.

The next minute the three moved toward the spot indicated. Their lives had accustomed them to many repulsive and terrible scenes, but all were visibly shocked by what they saw.

It was a magnificently-formed Blackfoot warrior, lying flat upon his back, while the bird had been tearing its meal from his vitals. He had undoubtedly been dead several days, else the odor would not have penetrated so far, but there was no bullet-mark upon his person, so far as the three could see without a more minute examination than any chose to make.

“What killed him?” asked Black Tom.

“The beast,” was the instant answer of Teddy.

“What makes you say that?” asked Tom, turning rather sharply upon the Irishman.

“Look how his hid is broke in,” replied Teddy, as he pointed downward. “Thar ar’ only two things that could break it in that shtyle.”

“Wal, what are they?”

“A shillalegh or the baste; and, as there is no one prisent that can wield the shillalegh but your humble servant, Teddy O’Doherty, be the same towken it must have bin the baste.”

The trappers acquiesced in the decision of their companion, and felt certain that the Blackfoot had been a victim to the fury of the brute that had so terrified them. It was plain that he had been struck a terrible blow on the head and face, a blow that had crushed in his skull as though it were an egg-shell.

Here there was a demonstration of what this fearful creature could do, when excited by anger, and it sent a natural shudder through the whole three.

“I tell yer,” said old Stebbins, in a solemn undertone, “it wouldn’t take much to turn me back ag’in toward the States.”

Black Tom was silent a moment, and then shook his head.

“No; thar’s gold around us, and we’ll stay long ’nough to git some of it to pay fur comin’ hyar.”

“I’d rather have the Blackfeet swarmin’ all around, than that ar’ single critter.”

“So would I; but how you goin’ to help it?”

“Kaap with me,” said Teddy. “The baste and mesilf ar’ on the bist of terms, as me Bridget remarked whin she threw her parlor-sofa (that she used as a bootjack) at me hid, and by r’ason of me prisence wid yees, ye’ll be thrated in the same ilegant shtyle.”

All this might be true, but there was little probability of it, and the two trappers were too great veterans in the service to place any reliance upon it. Indeed they believed it would be fatal foolhardiness for the Irishman to trust himself in its power again.

But they saw no remedy except to retreat, and they were not yet prepared for that. So they returned to the brook and resumed their hunt for the gold.

By this time the afternoon was well nigh passed, and little time was left for them to continue their work. They had nigh reached the place where they had discovered the auriferous particles the preceding spring, and they pressed on until they saw the yellow ore gleaming under the crystal waters, just as it had gleamed there for many a long year.

“Here’s some of the stuff any way,” said Black Tom, after he had lifted a lot in his hand and carefully scrutinized it.

“Yes; thar’s no mistake ’bout that,” replied old Stebbins. “We kin begin work right here, and make more in a day, than in a week by trapping. So, what do yer say? Do we resoom?”

“In the mornin’; we’ll take a sleep on it.”

Gathering up their implements, they started on their return.[45] By the time they were fairly in the cañon again it was fully dark, and, walled in as they were on either hand by such high, rocky cliffs, the darkness became so profound that they could scarcely see a step before them.

But they remembered the route too well to go astray, and they moved cautiously but unhesitatingly forward in the direction of the cavern that they had selected for their home, while at work in this region.

At the upper end of the cañon, indeed before it narrowed enough really to deserve the name, there was a mass of trees and undergrowth, through which the three hunters were making their way, when Black Tom uttered his low, sudden “’sh!” of alarm.

The others paused and listened, and looked around to learn the cause of this signal of their companion.

Like the faint twinkle of a star low down in the horizon, the three caught the glimmer of a camp-fire in this mass of vegetation and undergrowth.

“I knowed thar war others ’bout,” said Black Tom, after a moment’s pause; “whether they’re red or white-skins, we can’t tell till we find out.”

“Let’s do it,” said old Stebbins, and simultaneously the three set out toward the point of light, moving in the stealthy, silent manner that had become almost a second nature to them; but they had not gone far when Tom paused and said:

“Go ahead and l’arn what yer can, and I’ll go down to the cavern and wait for ye. Thar’s no need of all of us goin’ there.”

The trapper moved away from them as he spoke, not waiting to hear their opinions; and, as each party met with a curious adventure very shortly after, we will proceed to give them in detail.

Old Stebbins and Teddy O’Doherty crawled carefully over the rocks and bowlders until they were near enough to gain an unobstructed view of the camp-fire, when they paused, somewhat astonished.

Instead of seeing Blackfeet Indians or miners, as they expected, they descried a single man reclining before the fire, gazing dreamily into the embers, as though lost in reverie. He held a long, beautiful rifle in easy grasp, but there were no signs of any meal in preparation, or of any thing that was likely to engage his attention.