| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/reformedlogicsys00mclarich |

'Spirits are active, indivisible substances; Ideas [objects] are inert,

fleeting, dependent things, which subsist not by themselves, but are

supported by, or exist in minds or spiritual substances....The cause

of

Ideas is an incorporeal active Substance or

Spirit.'

London

SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO.

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

1892

[All rights reserved]

'Looking to the chaotic state of logic text-books at the present time, one would be inclined to say that there does not exist anywhere a recognised, currently-received body of speculation to which the title Logic can be unambiguously assigned, and that we must therefore resign the hope of attaining by any empirical consideration of the received doctrine, a precise determination of the nature and limits of logical theory.'

The object of the following treatise is to give an intelligible account of the principal facts of Mind, with a method for the right expression and criticism of Reasoning. It is based on principles not before applied to such a purpose. The current systems of Metaphysic are obscure and difficult simply because they start from false premises, not because the nature and operations of Mind cannot, if properly understood, be made as comprehensible to beginners as other branches of knowledge. The rules of Dialectic are quite within the capacity of any intelligent schoolboy, and should be an essential part of early education, like Arithmetic.

Let not the student be repelled at finding a philosophy reputed to be one of the most difficult taken as the basis of this work. It is Berkeleyism considerably modified. Also it is to be borne in mind [pg vi] that a philosophy is not to be judged by its primâ facie probability, but by its power of explaining many facts in a coherent and lucid way. A theory that does this should not be rejected for a seeming paradox at the outset.

Most of the theoretical and all the dialectical parts of this work can be adapted to Realistic thinking, by treating the judgments of the two Berkeleyan categories as intuitions instead of inferences.

Philosophies are either Ideal or Substantial. The ideal are those which resolve all things, actual and possible, into thought or consciousness. They seek to find in consciousness the reason and meaning of itself, or, if this be impossible, to account for each item in consciousness by defining its relation to some other item, or to some general mass of consciousness. This type of philosophy includes German transcendentalism and idealism, and some species of Buddhist and Persian metaphysic. European idealists are seldom consistent, for at the basis of their philosophies (or at the apex) they place God, who is not an item of human consciousness, actual or potential, and who therefore occupies, whether it be admitted or not, the relation of substance to human thought.

Substantial philosophies affirm that thought invariably inheres in some sort of Substance, for whose service it exists. It is incapable of independent being, and cannot be understood abstracted from its substance. It is intermittent, called up when wanted, and is liable to variation and aberration.

Substantialists differ however as to what the substance of human intelligence is. Some hold that it is the human body. Consciousness exists, they argue, for the use of the body and varies with its condition. This class of philosophers may be subdivided into Materialists and Metaphysicians (including logicians).

Materialists believe that consciousness is a product of the physical body—has therefore no existence before the body is formed or after it is dissolved. It is really as physical as the teeth or hair.

In metaphysic the intelligence is supposed to have a principle of existence apart from the body, and does not, or need not, share the fate of the body. The body is nevertheless regarded as the substance or superior fact during the union of the two. This is an eminently inconsistent philosophy, for if consciousness has an existence apart from body it must be in some other substance, and if so its relations to that substance are more important than its relations to the body, and should be the first object of inquiry. Metaphysic is in its development an idealism, since [pg 3] the connection admitted between body and thought is too slight to afford a sufficient explanation of intelligence, and no other substantial relation is known.

The notion that an invisible immaterial substance may underlie consciousness has occurred to some philosophers, among others to the illustrious Berkeley. His theory of Vision, which has never been refuted or even weakened, is founded on this hypothesis.

Berkeleyan substantialism combines the characteristic features of the other theories, and affords an easy solution of many difficult problems in philosophy. It has in common with idealism—whence it is sometimes, but erroneously, called by that name—that it regards all material bodies and things as facts or items of consciousness. It agrees with materialism that a substance is essential to consciousness, and that the consciousness of man serves the needs of his body, though that is not the highest use to which it can be put. It confirms the metaphysical view that intelligence is not, in its abstract or essential character, dependent on the body, and may therefore survive the body.

This is the theory on which the following logic is based: I shall refer to it briefly as Substantialism.

Substantialism has two main divisions—Ontology, which treats of the mental substance in itself, and Logic or Metaphysic, which deals with its consciousness. The present essay is specially concerned with logic, but certain ontological premises must be assumed to render the logic intelligible. This follows from the subordinate relation of consciousness to substance.

The substantial mind consists of two principal parts—a SELF and a PLASMA—the Atman and Akaśa of Sanscrit philosophers.

Self is the seat of Energy and Consciousness. The plasma is inert and unconscious; it protects the Self and receives, communicates, and retains impressions of experience, both the external and the internal1.

The Self would be conscious though isolated from other minds, at least from those of its own grade of being. It would feel the fluctuations of its energy. But the experience called 'external' depends on the mutual action of minds. It is the form into which their consciousness is thrown when they come in contact. It lasts no longer than the contact, and so has only a casual existence.

The constitution of the mind is not given by Berkeley, and on other points also we must supplement and correct his philosophy. He was wrong as regards the mental cause of the perception of the Inorganic or Dead.

Since external experience implies that another mind is operating upon ours, what mind is operating when we perceive an object that is apparently mindless? Berkeley replies that it is the supreme mind that is then acting upon us.

Many objections can be urged against this view. I will mention only one, which seems to me conclusive. By every canon of judgment we possess, the living or organised is better—more important and significant—than the lifeless and elemental; so if Berkeley's reasoning be valid the phenomena excited by finite and created beings are superior to those excited by their Creator. The movements of a living man are referred to a human mind—a putrescent carcase is a vision immediately induced by the Deity.

The beauty of the starry sky is irrelevant to the question. Apart from the finite life and thought that may be associated with the stars, they have no more philosophical importance than a spadeful of sand.

A more reasonable account of the inorganic is found in several ancient philosophies. Gnostics and Neo-Platonists referred the elemental to a cosmic mind (Demiurgos) intermediate between human beings and the Supreme. The demiurgic mind is inconceivably greater and more powerful than the human, but is not necessarily better in quality. It is the origin of all natural forces, and its organic processes are what we term 'physical laws.' This is the explanation of inorganic consciousness which I feel disposed to adopt, but to discuss it fully would carry us too far from the subject of this work.

The next point relates to the body. What is its function in substantialism? The brain, says Berkeley, is an idea in the mind, and he ridicules the notion that one idea should generate all other ideas. This is an argument against materialism. No doubt he would have admitted, though he does not say so, that the body-idea facilitates, or at least must precede, the experience of other ideas. He would not have denied that it is an instrumental idea.

Since his time an important discovery has been made with reference to the constitution of the body. I allude to the Cell theory. It is no longer possible [pg 7] to regard the body either as a self-moving machine (if this is not a contradiction in terms), or as a lump of 'dead matter' animated by the mind. It is a society of minute animals2, each having a certain degree of independent energy and liberty of movement. They are organised and governed by the human or animal mind with which they are associated. In short, the relation of the cell to the man is analogous to, if not quite the same as, the relation of the man to the cosmic being.

This discovery complicates the problem of 'external' consciousness, without however affecting the principles on which a substantialist would endeavour to solve it. Instead of conceiving human minds as coming into immediate contact in perception, we have to conceive the cellular systems of each as forming a medium between the two. We do not perceive the other mind immediately or intuitively; what we perceive intuitively is certain affections in our own organism, which we must first refer to the other body, and then to the mind behind that body. Our knowledge of other human beings is thus altogether inferential.

The cellular medium explains why we are not generally aware of the substantial constitution of other minds; it is veiled by the intervening organisms.

The relation of body to mind, the reason of embodiment, and so forth, are questions of prime importance in ontology, but in logic we are concerned only with the object in consciousness, without reference to the apparatus of perception. The instrument of intellectual perception may in its proper character be ignored.

All the current academic metaphysic is ideal. Materialists, when they attempt to explain thought, fail to attach it properly to the body, or to account for that large and important division of mental activity which has no bearing, direct or indirect, on bodily welfare. They drop their materialism at an early stage of their enquiry and continue on the metaphysical method.

Hence in none of the current systems is there any true principle of arrangement in the treatment of logical phenomena. Unless we know the use of a thing we cannot describe it, let alone explain it. We know not the relative importance of its parts, and we arrange them according to superficial resemblances, [pg 9] or on some arbitrary principle which conceals instead of revealing their meaning.

Substantial philosophy alone possesses a principle of coherence. The facts of consciousness are determined by anterior facts of substance, and there can be only one true mode in which to present them—they must follow and reflect the substantial order. They will thus appear as a consecutive and coherent system of ideas, no one of which could be otherwise placed without damage to the whole. This is perhaps the most important respect in which substantial logic differs from others.

The doctrine of Categories has to receive full development in order to elucidate the genesis of the 'material world.' Except to a substantialist the categories have no particular value, and so they are barely mentioned in the academic systems.

The theory of Reasoning or Dialectic (logic in the narrower sense) given in the following chapters, will be found totally different from the academic. It does not merely state in other words or metaphors the doctrines laid down in works of the Aristotelian type,—it declares that the theory of reasoning taught in these works is altogether false. Our argumentation is not conducted in syllogisms, either tacit or explicit. This has been suspected by several critics of logic, but no attempt has been made to substitute a more correct theory and method. [pg 10] Of course logicians do not always reason wrongly, and true arguments may be stated in the syllogistic form. What I mean is that logicians nowhere tell us in what right reasoning essentially consists, and for want of a distinct notion on the subject they all of them occasionally admit as valid, arguments that are not so.

The main dogma of substantialism should be kept in view in reading the following pages. It is mind alone that is conceived as having solidity and energy: material things are temporary forms of our consciousness; they have length and breadth but no depth, and they are without energy, even passive resistance. If an object cannot be removed at pleasure, what resists us is the other mind causing that object, not the object itself.

As far as possible I have utilised the existing logical terminology. But substantialism has notions which require special technical words, and I have not hesitated to invent such when necessary. On the other hand, I have rejected the latinisms of current logic, which have never been assimilated by modern languages. The English language is good enough for all the purposes of logic.

1: The mental substance is the fifth essence of the initiate Greeks and of Alchemists. They also called it chaos and first matter. 'Man was made of that very matter and chaos whereof all the world was made, and all the creatures in it: which is a most high mystery to understand, and must, nay is altogether necessary to be known of him that expecteth good from this art, being the ground of the wisdom thereof. Foolish men, nay they that the world holds for great doctors, say and tell it for truth, that God made man of a piece of mud, or clay, or dust of the earth, which is false; it was no such matter, but a Quintessential Matter which is called earth, but is no earth.'—De Manna Benedicto.

2: See Stricker's Manual of Histology; Bioplasm, and other works, by Dr. Lionel S. Beale, M.B., F.R.S.; and an article on the New Psychology, by A. Fouillé, in the Revue des Deux Mondes for October 15th, 1891.

The mind has at physical birth one uniform quality of plasma and consciousness. By education and experience a portion of the plasma is gradually changed, and the consciousness excited by this portion is what we call Intellect. The word may also stand for the plasma so differentiated.

The consciousness pertaining to the plasma left in its primitive state is Sentiment, which generally corresponds to what is termed the moral nature of man.

Intellect is a temporary condition arising out of the need to preserve the Self from hostile and inharmonious surroundings. The adaptation is artificial, and may therefore be well-done, or ill-done, or over-done. [pg 12] It is over-done when too much of the plasma and mental energy is devoted to intellectual purposes—when the individual has, to use a common expression, more head than heart. In this case the end is sacrificed to the means.

I conceive the intellect as a hardening of the plasma in its superficies, the formation of a sort of rind capable of receiving finer, sharper, and more enduring impressions than the plasma of sentiment; and, being harder, it is better able than the latter to resist enfeebling influences. Its duty is to challenge and inspect vibrations before permitting them to pass inwards to the region of sentiment. Yet the intellectual consciousness is itself a degree of sentiment, and in intellects not sufficiently trained it may be impossible to distinguish thoughts that are purely intellectual, from thoughts that are also to some extent sentimental. Upon minds of this sort the best-prepared arguments have no hold; they must be mixed with oratory and poetry to receive any attention. It need not be said that a mind which responds only to 'persuasive' language is feeble of intellect. It lives in the present only, and is incapable of far-reaching designs. It is to the intellect we owe the power of conceiving the past and future, and of laying plans for the future.

A mind properly intellectualised is, of its kind, strong and self-controlled. With the intellect defective [pg 13] the man exhibits passion, undue excitement and demonstrativeness. He responds to the least stimulus, like an exposed nerve; his energy is wasted in explosions. Sentiment is the inmost nerve of man—intellect its protecting sheath. The most carefully trained intellect is liable at times to be carried by assault or stratagem; then follows a feeling of emptiness occasioned by loss of energy. On the other hand an appearance of self-command may be really due to apathy,—the mind is of a low type and callous to influences that usually affect its species. If it is bad to be explosive, it is perhaps worse to be incapable of exploding.

Intellect is not the supreme or ruling intelligence of man. It initiates nothing. It is a light to direct our steps, but we do not walk where the light happens to fall—we make it fall where we desire to walk. Hence the diversity of occupation and intellectual accomplishments in men. Each acquires the sort of intellect he thinks will be sentimentally most serviceable to him; and on matters concerning which he has not learnt to reason he consults other men. We are not born rational beings; we are in no sense rational on all subjects; we are rational only on those few which we have mastered.

Men pretend to act from reason only, and perhaps they do on matters to which they are indifferent. But in general their rationality consists in finding [pg 14] pretexts for what on sentimental grounds they have already resolved to do, and in finding ways and means to carry out their resolves. Sentiment is the moving spring of conduct: intellect is the executive faculty. Those historical philosophers are mistaken who suppose the progress of mankind results from intellectual discoveries and inventions. These are effects, not causes, of progress—effects of sentimental disagreement with previous conditions.

Intellect is little more than an extension inwards of our senses. It is an epitome and rearrangement of their observations, and is as instrumental as they. We are not necessarily improved by a development of the intellect forced upon us from without. Education is sometimes a dagger put into the hands of an assassin. The best education is largely sentimental (moral), for that is not confined to preserving the mind we have—it gives us another and a better mind, and so indirectly improves the intellect.

This word has several meanings which it may be well to notice.

As veracity it means an agreement between our thoughts and our language. It supposes that we take [pg 15] reasonable pains to learn the conventional laws upon which language is founded, and then endeavour as far as possible to bring our speech in conformity with these laws. Since language is an art (like music) it may be acquired well or ill, so that a mistake in the use of a phrase or term is not regarded as untruth. There must be deliberate abuse of language to constitute a lie.

Agreement between an idea of memory and the actual experience—correct recollection—is another meaning of truth.

Also truth may signify agreement between an inferential thought and the fact to which it refers, although the fact has not yet been observed. In this sense truth must be construed liberally. We never foresee a future fact exactly as it will take place. Our anticipations are vague and our preparations for them general, but that on the whole is enough for our purposes. At least it is all that reason affords us. If we are absolutely certain of a future fact and can figure it in the mind precisely as it will take place, that means that it has already occurred so often that we are virtually using our memory, not our reason.

An inference may be considered true if it is the best we can draw from the information at our command, though in point of fact it may prove to be very incorrect.

There is no mass of speculative Truth which everybody ought to possess on pain of being considered foolish or miscreant. This notion, formerly so prevalent, betrays gross ignorance of the nature and function of intellect. It makes intellectual speculation an end in itself. Our ideas must be such as serve the uses of our sentimental or inner soul, and since the sentiments (tastes) of men vary widely, so ought also their intellectual ideas. Though change of sentiment modifies ideas, change of ideas does not modify sentiment. There is therefore no sort of good in uniformity of belief in itself. It is creditable to modern times that men have shaken off the procrustean beliefs of the Middle Ages, and are free to adapt their intellects to their real sentimental needs. The numerous sections into which speculative thought is now broken up, and the frequent changes of theory, are signs of healthy and active sentiment.

In matters of social policy, where large bodies of men have to carry out a single design, uniformity must be attained by persuasion or compromise. But such matters relate only to physical well-being, into which philosophical truth can hardly be said to enter.

This relative and, in the widest sense, utilitarian view of intellectual truth applies both to quantity and quality of ideas. We should not learn what we do not sentimentally require. That is waste of power. Useless [pg 17] knowledge is folly, said both Plato and Aristotle. To mistake knowledge to be the pursuit of man is to confuse the means with the end, says the author of the Bhagavad Gita.

The quality of our ideas must not be good beyond our necessities. If they are, we shall suffer by acting on them. They will land us in circumstances for which our nature is not fully prepared.

If there were an abstract or standard truth, it would be good for every species of being, and no doubt the thoughts of a man are nearer to it than the thoughts of a horse. Therefore a horse ought to be improved by receiving a human intellect. But if we could insinuate into a horse's mind the knowledge possessed by an educated man, we should spoil what may have been a good horse and produce a monstrous and horrible man. So is it with ourselves. If we could receive knowledge far in advance of our requirements or out of relation to them, it would drive us mad or be itself madness. Our constitution and necessities determine what we can know and what we ought to know. Not all possible knowledge is good, and what is good for some may be useless or bad for others. Schopenhauer says well3: 'The faculty of Knowing ... has only arisen for the purpose of self-preservation, and therefore stands in a precise relation, admitting of countless gradations, to the requirements of each animal species.'

If our interests were single and uniform, one consistent scheme of intellectual knowledge would suffice. We need never be in fundamental contradiction with ourselves. Every advance in knowledge would illustrate and confirm what we had already learned.

But we are not of this simple constitution. We are first and essentially minds, we are next and temporarily embodied minds, and in each of these characters we have distinct and, to a great extent, conflicting interests. Hence we have to acquire different species of knowledge and admit different standards of truth. The ideas that serve the interests of the embodied man are false to the same man considered apart from his embodiment, and contrariwise—false, in the sense of being useless and perhaps misleading.

Hence the existence of Common-sense for the embodied interests, and Philosophy for the purely mental interests. Science is common knowledge carried to its utmost perfection, but not partaking in the least of the philosophical character.

Realism is the notion of perception that is acquired with our common knowledge. It is seldom explicitly [pg 19] defined or defended, for in order to this a comparison with philosophic theories would have to be made, and the defects of realism would be apparent. The realistic view is so named by philosophers to distinguish it from their own views.

For corporeal purposes it is useful to believe, and it is therefore relatively true, that there is a real space which would exist although all objects were removed from it. Objects are real solid things stored in space like casks in a cellar. They have fixed dimensions notwithstanding that they appear to contract and dilate as we leave or approach them. It is quite 'natural' they should appear smaller at a distance. Distant perception is conceivable, therefore it is possible, and since calculations based on this assumption are verified by experience, it must and does take place. Time also is as real as space, and would exist by itself though space and its contents were annihilated. It is a sort of stream.

All these propositions are true for certain necessary purposes. We begin to form such ideas from the moment we are born, and during the years of infancy we are doing nothing else intellectually but working out the notions of space, time, magnitude, distance. Most of our school education is of the same kind. By the time we reach maturity realism has become so rooted in our intellect that—as regards the majority of men—no sceptical considerations are strong enough [pg 20] to unsettle them. For why? They enable the natural man to provide sufficiently well for his bodily needs and other needs depending therefrom, and he has therefore no motive for doubting his realism or for acquiring any other sort of ideas. He is quite right to abide by those which have answered his purposes.

It is not from without but from within that doubts arise as to realistic truth. They arise when the mind has acquired power over and above what is needed for bodily uses, and begins to think on its own account. Sentiments are felt which do not depend on or refer to bodily life, and a new intellect has to be formed to explain and protect these sentiments. This new intellect is Philosophy. It is the science and practical conduct of mind considered as abstracted from body.

Much of the obscurity of philosophy is traceable to the superstition of a fixed standard of truth which must be recognised universally. We are reluctant to accept philosophical hints and inferences because they conflict with truths that have been physically verified. Or—which is more common—we take up a few philosophical propositions and tack on to them all the science we know, believing they make a homogeneous whole, because truth must be self-consistent.

Time and labour would be spared if we could be told at the right moment that truth is expedience4, [pg 21] and that there is no need to harmonise philosophy and science. We are each of us two men in one, and each of these men must be allowed to think for himself. There is no reason why they should quarrel; there is no reason why they should even argue. The science in our mind should not be ousted to make room for the philosophy; let them exist together and work alternately. When the mariner is at sea he must mind his ship and study the weather; when he is on shore he may neglect both. So when we are navigating the body we have to think in categories proper to its safety; as philosophers we dismiss the realistic categories and think in other forms, but we need not then call the realism false or foolish. In its proper place it is right and true5.

Between realism and substantialism there is therefore no necessary conflict or competition. They are each indispensable. It is absurd to carry realism into philosophy, and no less absurd to carry substantialism [pg 22] into common affairs, or to reproach a substantialist because he acts and speaks occasionally like other people. It is probable however that in a community largely composed of substantialists the realism of common action would be less stringent than is now found necessary.

3: Will in Nature, 'Physiology of Plants.'

4: This does not apply to truth in the sense of veracity.

5: Greek philosophers never understood the dual standard of Truth, and insisted that philosophy was the best preparation for every sort of employment. The people, though generally unwise in political matters, had sense enough not to entrust the care of their temporal interests to philosophers, and so the universal utility of philosophy had few opportunities of being tested. A Macedonian king committed the custody of Corinth and its citadel to a philosopher, Persaeus, who was promptly expelled by Aratus—a mere soldier. Persaeus frequented the schools again, and on the well-worn theme that 'none but a wise man is fit to be a general' being brought up for discussion, he said, 'It is true, and the gods know it, that this maxim of Zeno once pleased me more than all the rest; but I have changed my opinion since I was taught better by the young Sicyonian.'—Plutarch's Life of Aratus.

Perception has already been partially defined. So-called 'external objects' are forms excited in our consciousness by pressure of other minds. The great permanent 'world' is due to the action of a cosmic mind with which we are intimately associated throughout our physical life.

Objects have a totally different sort of existence from minds, for whereas the latter are—at least relative to objects—self-existent, the former have no existence except during the act of perception. If minds could be all moved asunder from each other the whole objective world would disappear, yet the universe would be as full as before, for sensation occupies no room.

The appearances we interpret as distance are due to variations in the pressure or stimulus producing the object.

It will be convenient to call the more active mind Noumenon, the perceiving mind Subject. The mind that is subject on one occasion may be noumenon at another, and conversely. The true antithesis to subject is not object, but noumenon. Object has no antithesis, unless it be nonentity.

It is specially to be noticed that an object is not the cause of a sentiment. The knife we see or handle is not the cause of the pain it may inflict if driven into our flesh. Pains and pleasures signify that the noumenal action is powerful enough not only to excite objects in the intellect, but to penetrate inwards and excite sentiments also. It is the noumenon that causes both object and sentiment, as far as the energy exerted is concerned, but the variation of plasma in the subject is also essential to the distinction of object and sentiment.

The subject is not quite passive in perception. No consciousness takes place unless the subject is charged with energy. Further, since consciousness is confined to the Self and not inherent in the plasma, we perceive only such vibrations as reach the Self. If the Self is absorbed in one part of the mind, vibrations may take place in other parts without being noticed. The more energy we concentrate at [pg 25] the point or surface of contact (Attention), or otherwise bring to bear on the plasmic vibration, the more vivid is the object.

The fixing or circumscribing of attention so as to break up our experience into distinct things or objects is an acquired art, whence we may infer that the intellectual experience of infancy is a vague whitish surface, not clearly distinguished by colour or movement.

Kant and other philosophers admit that objects are caused by noumena, but insist that we can never know or conceive what a noumenon is.

Why not? Each of us knows himself to be the noumenon of many phenomena; he has no doubt that many other phenomena are caused by minds like himself, and it is easy to extend this principle to all phenomena whatever. They are all caused by minds more or less like human minds. This is a useful conclusion, although we are not able to imagine very accurately the mind of an insect or of a being of cosmic dimensions. It is not necessary we should, but the most general inference of this sort is better than none at all, and better than the notion that phenomena are self-existent and self-moving.

Although simple and intelligible when stated in the abstract, perception is difficult to work out in detail. Objections start up on every side, and it requires the utmost patience to reduce them to what [pg 26] they are—inferences from the realism we are supposed to have discarded. It is only when we try to dislodge realism wholly and consistently that we find how fast its hold upon our intellect is. Critics who profess to treat Berkeley's substantialism seriously and sympathetically, constantly bring up against it arguments of the most naively realistic kind. They have no adequate conception how enormous is the revolution in thought involved in substituting substantialism for realism. It is a complete dissolution of the natural thought and belief; it means the construction of a new heaven and a new earth with laws to which we have been hitherto unaccustomed. The old science is of little or no use to us as substantialists.

Philosophy is not an advance or correction of science. In so far as the latter claims to be absolutely or philosophically true, substantialism abolishes it in dispensing with the notions of real matter and real space. Hence it is quite irrelevant to point out that substantialism is inconsistent with (say) the doctrine of physical evolution. This theory, though so new, is now often referred to as axiomatically true, whereas it is an inference, the evidence for which, even to many realists, is far from conclusive. Whether it be considered true or not in science, physical evolution is quite untrue in philosophy.

An imprint or mould of the object is generally left in the plasma of the subject. The imprint is deep, clear and lasting in proportion to the strength of the exciting cause and the degree of energy assigned to the perception. When the noumenon withdraws the object does not at once disappear, for if the energy of attention remain the mould left by the noumenon serves to excite a consciousness similar to the object, and this is what we call an Idea.

What Hume says as to an object differing from an idea in nothing but vividness is evidently incorrect. Objects are generally, but not always, more vivid than ideas, and when an object is present we have an indefeasible conviction of being acted on by something not ourselves, which conviction is not present [pg 28] in recollection. We may not be able to give a satisfactory reason for the conviction—if we are arguing idealistically we certainly shall not—but the fact that it is there serves to mark off objects as a class of consciousness distinct from ideas, irrespective of their vividness. If an object were once seen clearly and so remembered, and were afterwards seen indistinctly through a mist, the latter consciousness would (according to Hume) be the idea and the former the object. Such an application of words would be an abuse of language.

There are of course no innate ideas of objects. There is innate consciousness—the sentimental.

Ideas are of three kinds—Particular Ideas, General Ideas, Imaginary Ideas—corresponding to the so-called faculties of Memory, Generalisation or Classification, and Imagination.

When the energy of attention is exhausted or withdrawn the idea also disappears, but it may be revived by bringing the energised Self in contact with the imprint again, and this operation can be repeated indefinitely. The power of exciting ideas of past [pg 29] experience is Memory; any particular exercise of memory is Recollection.

The imprint of an object is not absolutely permanent and is probably never quite true. It begins to lose sharpness at once, but if the object be frequently observed and much remembered, it will retain its general character for years. The exercise of memory, instead of wearing out the imprint as would be the case with a material negative or engraved plate, keeps the channels open6. Persons of little experience remember well, for their energy of attention is not distributed over many different ideas; it travels continuously round a small circuit. One hears ignorant persons recounting events that happened years ago, with as much detail and with almost as much sentiment as if they had taken place the day before. A 'good memory' is no proof that the quality of mind or thought is good. All experience is not worth remembering. One of the most difficult things in moral culture is to get rid of the imprints of ideas that are out of harmony with our improved sentiment.

Although the imprints in our mind may close up and leave scarce a cicatrice, the part that has been once disturbed is never the same as the virgin plasm. It remains a little more tender. It may not reopen to ordinary stimuli, but an extra agitation of the plasm [pg 30] will rip up the closed furrows, and give us back scenes in our life that had long ceased to be recollected. A great agitation in all parts of the mind may revive what appears to be the whole of our past experience in a simultaneous recollection. So I explain the extraordinary lucidity that sometimes occurs in fevers and in moments of extreme terror.

It is also conceivable that the egoistic energy may be so strong as to destroy outright the moulds of thought, as a flood sweeps away the banks of a river. 'We sometimes find a disease quite strip the mind of all its ideas, and the flames of a fever in a few days calcine all those images to dust and confusion which seemed to be as lasting as if graved in marble'7.

What is called 'decay of the mind' in old age is merely the loss of the plasmic images. Since intellect would not have been formed in the first instance if it had not been wanted, it is to be expected that it will fade out of the mind when it is no longer wanted. So far as the realistic intellect is concerned, we return to 'second childhood' and the uniform sensibility we had at birth.

No philosophy but the substantial explains memory. Idealists and metaphysicians, who recognise only consciousness, are utterly unable to account for [pg 31] the revival of a shadowy sort of objects in the absence of their original causes. Here is the melancholy confession of John Stuart Mill on the subject:—

'If we speak of the Mind as a series of feelings, we are obliged to complete the statement by calling it a series of feelings which is aware of itself as past and future: and we are reduced to the alternative of believing that the Mind, or Ego, is something different from any series of feelings, or possibilities of them, or of accepting the paradox that something which ex hypothesi is but a series of feelings, can be aware of itself as a series.

'The truth is that we are here face to face with that final inexplicability at which, as Sir W. Hamilton observes, we inevitably arrive when we reach ultimate facts; and in general one mode of stating it only appears more incomprehensible than another, because the whole of human language is accommodated to the one, and is so incongruous with the other, that it cannot be expressed in any terms which do not deny its truth. The real stumbling-block is perhaps not in any theory of the fact, but in the fact itself. The true incomprehensibility perhaps is, that something which has ceased, or is not yet in existence, can still be, in a manner, present: that a series of feelings, the infinitely greater part of which is past or future, can be gathered up as it were into a single present conception, accompanied by a belief of reality. I think, by far the wisest thing we can do is to accept the inexplicable fact, without any theory of how it takes [pg 32] place; and when we are obliged to speak of it in terms which assume a theory, to use them with a reservation as to their meaning8.'

Memory an ultimate fact! It is the first that stares us in the face on beginning to philosophise, and it haunts us through all our subsequent speculations. It is the 'dweller on the threshold' of philosophy, which unless we overcome will overcome us, and frustrate our magic.

The passage quoted does not show Mill's usual candour and consistency. His philosophy has broken down on an essential point, and he is reluctant to admit it. He tries to throw the blame on other things, and recommends that those who think with him should maintain a discreet silence on the subject of memory, or if obliged to speak of it do so in ambiguous language. That is hardly honest, and is bad philosophical practice. What we know or think we know we may leave alone—it will not run away; it is what we are conscious of not knowing that should receive our persistent attention.

Materialism presents at first sight the data out of which to construct a theory of memory, for it recognises the dependent character of consciousness and takes body to be its substance. Does the body show any marks or traces of thought that may serve to [pg 33] revive ideas in the absence of objects? None have yet been discovered. Nerves are used in objective observation, but they do not appear to be essential either to recollection in general or to any of the more elaborate forms of internal thought. The brain is used only when giving expression to thought.

Memory is noticed by everyone, even the least metaphysical. Persons who are incapable of understanding the difference between object and subject or general and particular, are yet perfectly well aware of the difference between remembering and forgetting. The phrases relating to this distinction are the commonest in every language. Memory is conspicuous—notorious—palpable. It is the pivot on which the whole mental system revolves. It cannot be gainsaid or ignored. There is no profit in boycotting it in the manner recommended by Mill—it must be faced and explained. 'How do you account for memory?' should be the first question addressed to one who pretends to have a science of mind. If he has no plausible answer to give, his system is not worth discussion. A philosophy without a theory of memory is like an astronomy without gravitation.

Sentiments are remembered and recollected like objects. For instance, a boy is punished for doing wrong and has pain; he does wrong again and is haunted with the fear of being punished again, which is the recollected and anticipated pain. We have thus two species of sentiment corresponding exactly to object and idea. The word 'feeling' is appropriate to the first, 'emotion' to the second. 'Passion' is a strong degree of either.

Objects that are associated with feelings are better remembered than those that merely affect the intellect, for there is a double memory at work—one in the core and one on the surface of our mind.

Sentiments are not susceptible of the same degree of analysis as objects. The inner matrix is more fluid and does not keep details. Apart from the objects associated with feelings, there is not much opportunity or need for classifying them. We are happy, wretched, or indifferent—that sums up the sentimental experience.

No two moral philosophers give the same list of sentiments. Some are satisfied with two—pain and [pg 35] pleasure. Spinoza gives a list of forty-seven9 sentiments, which includes luxury and drunkenness. It is evident that luxury is a general term which covers many different forms of feeling, and if the feeling of intoxication by alcohol is worth mentioning, so also must be the intoxications by opium and tobacco; and if these are included we must admit the feeling of nausea, which brings us to the sentiments associated with all diseased conditions of body or mind. Such distinctions are superfluous, for if the sentiment is purely personal and not associated with an external object, it is not of any general interest; if associated with an object and common to many persons it is best defined by reference to the object—as the pleasure of smelling a rose.

We have sometimes feelings of elation and depression for which we cannot find an internal reason nor yet an objective sign. Many of the so-called religious experiences are of this sort. So also are the sudden sympathies and aversions we feel towards certain people and places. Here there is an object, but we [pg 36] cannot find anything in the object that can be taken as specially significant of the feeling. We are said not to be able to 'analyse' our feeling, that is, assign it an object as cause.

These abnormal feelings may be explained by supposing that some external influences succeed in reaching our sentiment without exciting our intellect. Considering that intellect is artificial and may be very imperfect, and also that its efficiency depends to some extent on its being less sensitive than the original mental nature, it is reasonable to conclude that subtle emanations from our surroundings may occasionally affect us without exciting the intellectual consciousness. Panic, inspiration, mesmerism, and other 'occult' influences are probably due to this cause. If we further assume that sentiments so excited may then, by association, excite appropriate ideas in the intellect of the recipient, we have a likely explanation of what is called 'thought-transference.' Since ideas excite emotions, it is reasonable to suppose that feelings may excite ideas, or even the illusion that objects are being perceived.

Most ideas, except the particular (which are copies [pg 37] of single objects), are associated with a consciousness of resemblance and difference which arises in the following manner.

When new experience simply revives the imprint of a former experience we call it the same object or objects, though it is not numerically the same, being different at least in time. If a totally new imprint is made in the mind the experience is quite novel or strange, but we do not call it different.

Experience is usually neither quite the same as before nor quite strange, which means that the present noumenon has partially revived an old imprint and made a partially new one.

In this case we have a quadruple consciousness. There is first the present object; next the recollection of the object originally associated with the same imprint; thirdly, a consciousness of resemblance between the new and the old (the present object and the recollected idea) in so far as the imprints coincide, and (fourthly) a sense of difference in so far as they disagree. The limitation of resemblance gives rise to the sense of difference—a negative consciousness—and the shock of difference emphasises the resemblance. This is Comparison, the common basis of Generalisation and Imagination.

6: As if the image had the form of a stencil.

7: Locke, Essay on the Understanding, ii. x. 5.

8: Exam. of Hamilton's Philosophy, p. 212-3.

9: I append Spinoza's list, and print in italics the sentiments that appear to me to be emotions as distinguished from feelings. Desire—Pleasure—Pain—Wonder—Contempt—Love—Hate—Inclination—Aversion—Devotion—Derision—Hope—Fear—Confidence—Despair—Joy—Grief—Pity—Approval—Indignation—Overesteem—Disparagement—Envy—Mercy (or goodwill)—Self-contentment—Humility—Repentance—Pride—Dejection—Honour—Shame—Regret—Emulation—Thankfulness—Benevolence—Anger—Revenge—Cruelty—Daring—Cowardice—Consternation—Civility (or deference)—Ambition—Luxury—Drunkenness—Avarice—Lust. Pollock's Spinoza, ch. vii.

General Ideas are formed by the coincident imprint of several objects in some respects different, but which have all a resemblance as objects, and are besides the signs of the same sentimental effect. If the effects are different the confusion of the objects occasions practical error, as when we mistake one man for another whom he closely resembles. Though the sentimental utilities should be the same, the object cannot be reduced to a common idea if they are quite dissimilar: for example, a sand-glass and a watch have similar uses, but they cannot be generalized. The value of generalisation to a thinker is that it economises memory and recollection by making one common or average idea do duty for [pg 39] many particular ideas. Let us follow the process in detail.

The first perception of an object leaves an imprint in the substance of the intellect. A second perception partially resembling the first revives the first to the extent at least of the resemblance. Supposing this is done by a hundred similar objects it is plain that the resembling properties will have been experienced a hundred times, whereas the distinguishing attributes may have been felt a few times only, in some cases only once. Unless we have special reasons for observing the differences and so deepening the impressions of them, they will fade from our memory at a rate corresponding to the paucity of experiences. The most general idea will last longest because there the impression has been very deep. Our idea of Man or Animal will on this principle, as it is found to do in fact, outlast our memory of many concrete men and animals.

The objects that contribute to form a general idea or Class are commonly said to 'belong to,' or to 'inhere in,' or to be 'brought under' the idea or class. All these metaphors are wrong and occasion mistakes. Generalisation is nothing but condensed or epitomised recollection; it is practised by ourselves for our own convenience, and does not imply any essential or extra-personal relation between the objects. We are free to classify things in any order we find useful. [pg 40] A farmer's classification of some animals into cattle, game, fowls, birds, and vermin, is perfectly legitimate, for each species is based on a different utility for him.

We should distinguish general ideas which we ourselves have drawn from our primary experience, from the ideas suggested by verbal definitions of general ideas formed by other minds. Supposing the objects in question to be quite unknown to us, the definitional idea is more like a particular or imaginary idea than a general idea. It is a single thin rigid idea, utterly unlike the flexible suggestive thought evolved from a large mass of personal experience. Definitional general ideas are as unsatisfactory as described objects, but we are sometimes compelled to use both when personal experience is totally wanting.

It is a common error to suppose that general ideas cannot exist in the intellect without words by which to name them. Words and other modes of marking ideas are useful in all departments of thought, but not more necessary in general thought than in any other. An active intellect makes thousands of observations and scores of general ideas which it may have no means or wish to express in language.

Generalisation is very like the operation called composite photography. A number of persons are posed in the same attitude and partially photographed on the same plate. The result is an average or mean [pg 41] likeness of the whole group, but not an exact portrait of any individual. So general ideas are 'means' or 'averages' of many resembling but slightly differing objects.

There are other things in the photographic art remarkably similar to intellectual thinking. The gelatine film behaves very like the mental plasma: only one other physical object (so far as I am aware) is a better image of the plasm.

In theory the object or phenomenon has no importance. Even when it has the quality we call 'beauty,' that is not a property of the bare object, for it is not seen by every person or animal with good eyesight; it is a sentimental effect associated with the object. Hence we might, if it were possible, ignore all objects except those which have value to us as signs of sentimental effects.

But in practice we cannot do this. Objects are thrust upon our notice which we cannot avoid, and which have no sentimental interest for us. These objects are necessarily classified according to their phenomenal appearance only, and such ideas lack an essential characteristic of true general ideas. But we cannot prevent their formation in the mind, for generalisation is merely a kind of abbreviated memory, and, objects being once perceived, their recollection is to a great extent beyond our control.

Artificial and adventitious utilities produce the same kind of one-sided generalisation. If society pays a man in fame or money to observe and describe certain things, his classification of them will be purely phenomenal. He will classify dogs with wolves and nightshade with potato, and will lump together the whole population of a country in one class, although it consists of the most divers elements—fools and philosophers, rogues and righteous, saints and sinners, patricians and plebeians. These are differences much more important than sameness of nationality, colour, race, or language.

This practice, no doubt, gives symmetrical classifications. The greater classes are subdivided into subordinate classes, and these again into lower classes in a many-stepped series. Gradation occurs also in true generalisation, but not to the same extent.

If we confine our observation to things that are much like each other, the average idea will not be greatly different from a particular idea: this is called lowness in generality. If we run together quadrupeds, bipeds and fishes, we shall have a much higher general idea: the average will be very unlike any concrete animal. The higher we generalise the smaller becomes the content of the idea, but the wider its extension, that is, the realm of objects from which it has been drawn, or which it is considered to represent. The usual practice is to generalise by fine [pg 43] gradations. Get the general idea of sheep, then of cow, then of horse; then average the averages. The result is much the same if we run all the objects together and average them in one operation, but the slower process gives the neater results. The gradations of generality are distinguished by names such as (beginning from below) variety, species, genus, class, family, kingdom.

'Conceptualism' is the metaphysical doctrine now prevalent with respect to general ideas. They are regarded not as objects nor as essences, but as forms of consciousness depending more or less on our own mental activity. This is true enough so far as it goes, but without a substantial plasm to hold the 'concept' its formation and endurance are quite inexplicable.

Matter is the name given to the most general idea we can form of objects. It is supposed to cover all of them. In other words, the content or 'essence' of the idea is the attribute or attributes common to all objects without exception. It is the universal [pg 44] objective minimum—the least objective experience consistent with the experience being objective. Some have attempted to define this general idea more precisely by identifying it with some abstract property such as extension, resistance, etc. An object may be material without offering any resistance to human energy, as a beam of light. A material object may also be without extension, as a sound or smell. The only quality left to matter is bare objectivity, namely, that it is a form of consciousness excited in a mind by some other mind, not occurring spontaneously. This seems to me the only true connotation of matter.

Matter is not the antithesis of mind; it is a mere affection of mind. The two are not in any proper sense co-ordinate or equipollent. They are to each other somewhat in the relation of a mirror to an image reflected from it. Mind is to each of us a concrete primary experience—the feeling of personal power and identity. Matter is a general idea arising from the comparison of objects in consciousness. No two things could well be more diverse.

Since general ideas are products of our own mental energy, and matter the most general of all, it is the farthest removed from the concrete objective condition, and so it is literally true that we never objectively perceive matter though we constantly perceive material objects. It is as impossible to see, [pg 45] touch, or taste matter as it is to ride the general idea Equus or dine off the general idea nourishment. In denying the objectivity of matter we do not deny the objective reality of things: we merely decline to confound a general idea with the objects that have contributed to form it. We decline to be mystics, in the sense defined by J. S. Mill10. The belief in the external existence of matter is a form of mysticism; the Hindus call it maya, meaning illusion.

Some metaphysicians argue that since phenomena appear only in conjunction, we are compelled by the constitution of our nature to think of them conjoined in and by something, and this imaginary foundation and cement is another meaning of the word 'matter.'

For myself I feel no such compulsion. When things are complex I recollect the several properties as cohering together, and when I abstract one or some for special consideration, I sometimes think of the others as forming a 'substance' in which the abstracted properties inhere. But I cannot discover any inherence or coherence except the mutual, and the notion of an invisible material setting which holds all the parts of a thing together seems to me superfluous and unwarranted. If it existed it would not be, as logicians argue, something superior and antithetical [pg 46] to phenomena; it would be simply an inferred or latent phenomenon like the luminiferous ether of science. The material substance is evidently a groping of the mind after the noumenal (mental) substance which causes the appearance of objects.

Nominalists deny the existence of general ideas as distinct from particular ideas. Most of them affirm that we employ general or common words to signify the common properties of similar things, but that we are incapable of thinking of these common properties apart from the other properties that accompany them.

Why we should wish to use signs of things we cannot think about, or how a word can be a 'sign' when we are incapable of attaching a definite meaning to it, are points not satisfactorily cleared up by nominalists.

Considering how well Berkeley's principle, combined with the plasmic theory, accounts for generalisation, and how inevitable it is that there should be general ideas distinguishable from particular ideas by superior brilliancy and endurance, it is surprising [pg 47] to find in Berkeley one of the most convinced and eloquent of nominalists. His views on the subject have so much weight with philosophers that I must examine them at length.

'It is agreed on all hands,' he writes in the Introduction to his Principles, 'that the qualities or modes of things do never really exist each of them apart by itself, and separated from all others, but are mixed, as it were, and blended together, several in the same object. But, we are told, the mind being able to consider each quality singly, or abstracted from those other qualities with which it is united, does by that means frame to itself abstract ideas. For example, there is perceived by sight an object extended, coloured, and moved: this mixed or compound idea the mind resolving into its simple constituent parts, and viewing each by itself, exclusive of the rest, does frame the abstract ideas of extension, colour, and motion. Not that it is possible for colour or motion to exist without extension; but only that the mind can frame to itself by abstraction the idea of colour exclusive of extension, and of motion exclusive of both colour and extension.'

Abstract ideas do not form a fourth class of ideas but are fractions of particular, general, or imaginary ideas, and may (as Berkeley, reporting the metaphysical doctrine, says) be single or partial properties mentally detached from the collective properties forming an object. In this case they are abstracted properties, [pg 48] not ideas. Since general ideas are less complete than the particular ideas from which they were drawn, they are abstract ideas in so far as they are partial ideas; but all abstract ideas are not general ideas. Berkeley's nominalism is based on the supposed impossibility of forming any sort of partial idea, and he now proceeds to reproduce the metaphysical account of the general abstract idea.

'And as the mind frames to itself abstract ideas of qualities or modes, so does it, by the same precision or mental separation, attain abstract ideas [general ideas] of the more compounded beings which include several co-existent qualities. For example, the mind having observed that Peter, James, and John resemble each other in certain common agreements of shape and other qualities, leaves out of the complex or compounded idea it has of Peter, James, and any other particular man, that which is peculiar to each, retaining only what is common to all, and so makes an abstract [general] idea wherein all the particulars equally partake—abstracting entirely from and cutting off those circumstances and differences which might determine it to any particular existence. And after this manner it is said we come by the abstract [general] idea of man, or, if you please, humanity or human nature; wherein it is true there is included colour, because there is no man but has some colour, but then it can be neither white, nor black, nor any particular colour, because there is no one particular colour wherein all men partake. So likewise there is [pg 49] included stature, but then it is neither tall stature, nor low stature, nor yet middle stature, but something abstracted from all these. And so of the rest. Moreover, there being a great variety of other creatures that partake of some parts, but not all, of the complex idea of man, the mind, leaving out those parts which are peculiar to men, and retaining those only which are common to all the living creatures, frames the idea of animal, which abstracts not only from all particular men, but also all birds, beasts, fishes and insects. The constituent parts of the abstract idea of animal are body, life, sense, and spontaneous motion. By body is meant body without any particular shape or figure, there being no one shape or figure common to all animals, without covering either of hair, or feathers, or scales, &c., nor yet naked: hair, feathers, scales, and nakedness being the distinguishing properties of particular animals, and for that reason left out of the abstract [general] idea. Upon the same account the spontaneous motion must be neither walking, nor flying, nor creeping; it is nevertheless a motion, but what that motion is it is not easy to conceive.'

This is a fair paraphrase of the accounts given by metaphysicians of the manner of forming general ideas. It is also in itself a perfectly correct account of the process, considered simply as a manifestation of consciousness or a succession of states of consciousness, that is, apart from the substantial plasmic operation of which it is merely the symptom. Berkeley however [pg 50] denies that it is a true statement of what takes place in the mind of consciousness.

'Whether others have this wonderful faculty of abstracting their ideas, they best can tell; for myself, I find indeed I have a faculty of imagining or representing to myself, the ideas of those particular things I have perceived, and of variously compounding and dividing them. I can imagine a man with two heads, or the upper parts of a man joined to the body of a horse. I can consider the hand, the eye, the nose each by itself abstracted or separated from the rest of the body. But then, whatever hand or eye I imagine, it must have some particular shape or colour. Likewise the idea of man that I frame to myself must be either of a white, or a black, or a tawny, a straight, or a crooked, a tall, or a low, or a middle-sized man. I cannot by any effort of thought conceive the abstract idea above described. And it is equally impossible for me to form the abstract idea of motion distinct from the body moving, and which is neither swift nor slow, curvilinear nor rectilinear; and the like may be said of all other abstract general ideas whatsoever. To be plain, I own myself able to abstract in one sense, as when I consider some particular parts or qualities separated from others, and which, though they are united in some object, yet it is possible they may really exist without them. But I deny that I can abstract from one another, or conceive separately, those qualities which it is impossible should exist so separated; or that I can form a general notion, by abstracting from particulars [pg 51] in the manner aforesaid—which last are the two proper acceptations of abstraction. And there is ground to think most men will acknowledge themselves to be in my case. The generality of men which are simple and illiterate never pretend to abstract notions [general ideas]. It is said they are difficult and not to be attained without pains and study; we may therefore reasonably conclude that, if such there be, they are confined only to the learned.'

It is quite true that 'the simple and illiterate never pretend to abstract notions,' for the sufficient reason that they do not know the names of their mental operations, even if they are capable of discriminating them. For the same reason they do not pretend to talk prose or to be realists.

The practice of every profession and craft, even the humblest, involves abstraction and generalisation. The objective properties associated with a given utility have to be abstracted from those which are indifferent, and this is what enables men of experience in any branch of industry or art to form a speedy judgment on matters touching their special affairs. It is in part what distinguishes the 'professional' from the 'amateur.'

Berkeley's disclaimer of any power in himself to form general ideas is no doubt sincere, and he is justified in reasoning from himself to others. But the point at issue is, whether Berkeley in this instance correctly analysed his own mental processes. The [pg 52] fact that he was correct in some points of great importance does not preclude us from surmising that he may have been wrong in others of less importance. In comparison with his discovery of the substantiality of mind, his oversight on the subject of abstraction is a bagatelle.

He explains the existence of general words on the theory that they are names of particular ideas which we use to represent all similar ideas.

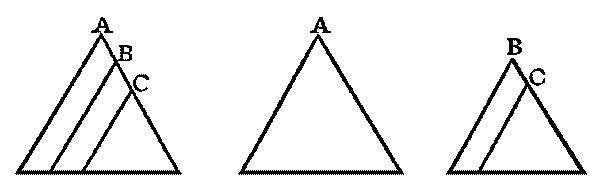

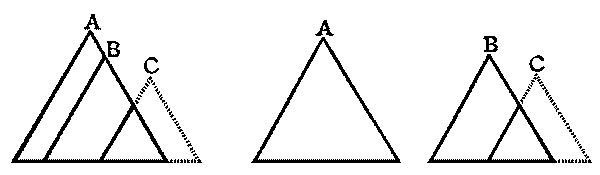

'... an idea which, considered in itself, is particular, becomes general by being made to represent or stand for all other particular ideas of the same sort. To make this plain by an example, suppose a geometrician is demonstrating the method of cutting a line in two equal parts. He draws, for instance, a black line of one inch in length: this, which in itself is a particular line, is nevertheless with regard to its signification general, since, as it is there used, it represents all particular lines whatsoever; so that what is demonstrated of it is demonstrated of all lines, or, in other words, of a line in general. And, as that particular line becomes general by being made a sign, so the name "line," which taken absolutely is particular, by being a sign is made general. And as the former owes its generality not to its being the sign of an abstract or general line, but of all particular right lines that may possibly exist, so the latter must be thought to derive its generality from the same cause, namely, the various particular lines which it indifferently denotes.'

These extracts will suffice to show what was Berkeley's doctrine on the subject of general ideas.

With respect to the analogy supposed to exist between the generality of a name and the generality of a general idea, it has to be observed that a name owes its generality solely to its being the sign of a general idea. It is an imputed or conventional generality,—in its proper character a general name is concrete and individual. Also it does not resemble the thing it signifies (the general idea), nor the concrete things from which that has been derived.

The generality of a general idea, on the other hand, depends altogether on its resemblance to many particular things. It is independent of convention. Hence there is no real analogy between the two generalities.

Considering that Berkeley professes himself unable to imagine abstract properties, it is surprising how easily and naturally he writes about geometrical lines—which are abstract properties. Probably he means concrete strokes.

What sort of representation can subsist between one concrete stroke and every other concrete stroke? If it is straight it will not correctly represent a curve; if it is curved it will not represent a straight stroke. A stroke an inch long cannot stand for a stroke a hundred miles long; a black stroke does not properly represent a red stroke. So it is incorrect to say that [pg 54] 'what is demonstrated of it is demonstrated of all strokes, or, in other words, of a stroke in general.' A particular object can stand only for itself, and if general words stand for many things it is not by direct representation, but because they first suggest general ideas, which are the true substitutes of many particular things.

A reference to geometrical objects, themselves so abstract, is a doubtful mode of showing how well one concrete thing can represent others. Had Berkeley taken a more complex object as his general representative he would have seen the weakness of his argument. Suppose a biologist has to discourse on a province of animal life comprising many species, and takes an individual of one species as a representative of the whole. His sample is perhaps a hare, but he has to treat of birds and fishes. What is to prevent his hearers from concluding that birds are furred animals and fishes quadrupeds? Are they to be expected to see in the hare only the properties common to all the animals reviewed? If so they have the power denied them by nominalists of forming a pure general idea, and the hare is superfluous. The common properties could have been defined and imagined without a concrete specimen, with irrelevant attributes, being brought into the discourse.

All nominalists insist that if we think long on a [pg 55] general idea it becomes particular, and from this they argue that it is not, and never has been, a general idea11.

The experiments of this sort proposed by logicians are misleading, because we are without the ordinary motives for thinking generally. In practical thought we have some sufficient reason for attending to a fraction of consciousness and excluding the rest, and the irrelevant qualities are distinctly less charged with attention than the principal quality.

The power of abstracting thought is a matter of education. It is that ruling of the spirit which is more difficult than the capture of a city. We have to master the restless energic Self and fix it down on a particular plasmic figure, or a mere point or edge of one, preventing the energy from spreading to adjacent images. That is irksome and fatiguing, but it is only a high degree of the faculty everyone possesses of distinguishing particular objects from each other. Some minds are so flaccid that you cannot hold them to one subject, even the most particular and obvious, for five minutes at a time. Training enables us to bring into the focus of attention just what we wish to observe or think about, and [pg 56] leave the rest in the background, however closely it may be connected with the matter that immediately interests us. But for this power much of our energy would be expended to no purpose. Abstraction is simply attention of a minute and concentrated kind—a bringing of our energy of observation or recollection to a fine point.

When abstraction need not be prolonged—when we are free to pass rapidly from one general or abstract idea to another—there is no difficulty in partial thinking. We skim over the plasmic imprints, lightly brushing the surface of each where it is most prominent and therefore most general, but not pausing to recollect particulars. It is this rapid delicate touch we oftenest use in actual thought; but when for purposes of experiment we come down heavily on an imprint, then the Self overflows to adjacent channels and particular memories are stirred up, in spite of every effort to limit our attention.

So common and easy is rapid general thought that it is constantly used as a substitute for concrete thought, when a sketchy treatment of things is all that is wanted.

'A bird has alighted on the fence.' The speaker saw a particular concrete bird, and might have tried to describe it in the concrete. But the attributes that rendered it concrete are supposed not to be of present [pg 57] importance, and the hearer is consequently invited to think only of bird in general. Would a nominalist affirm that in such a case the words are meaningless unless the idea is concreted—unless the general sketch is filled out in detail?

Take another example. 'The man sat by the window overlooking the river that flowed towards the city.'

Here all the nouns are general, but the picture is individual and concrete. It is also quite intelligible, as a sketch. We can think of a man without assigning to him any particular type of face, or colour of hair, or stature, or age, or clothing. Our idea is the general idea man used as a sketch of a particular man. He is in a house because he is looking through a window, but we do not stay to imagine the house as cottage, inn, or mansion. We call up the general idea house, which is definite enough for our purpose, and we cannot doubt for a moment that we have such a general idea. The river may be wide or narrow, straight or crooked, navigable or not, but we think only of the general idea river, which is water flowing between banks. And surely we can imagine a general city without giving it any definite size, or form, or nationality, or number of inhabitants!

These considerations clearly demonstrate that we have general ideas, which are not merely concrete [pg 58] ideas used as examples, and if we can employ them in the manner just indicated, where a light superficial recollection is all that is necessary, we can equally well use them in their more legitimate character, as signs of certain general utilities.

Generalisation has been the bane of European philosophy. It has monopolised well-nigh the whole metaphysical attention. It has been considered the radical fact of mind from which all others have grown, whereas it is no more than a method for abbreviating recollection. It neither reveals to us new things, nor reduces the multiplicity of things actually existing.

Plato insisted on the importance of general thought as against the fluctional idealism of Heraclitus, but he was wholly mistaken as to the nature of general ideas. He thought they were external objects—also types and causes of primary objects. But patterns are not causes, and general ideas are quite obviously suggested by things, not things derived from general ideas. The notion that the general idea is either the [pg 59] cause, or an image and revelation of the cause, of things is an error of perennial recurrence. In some form or other it is always with us.

Plato also taught that general ideas are recollections of knowledge acquired in the condition prior to embodiment, which the objective experience of this life serves to revive. These several doctrines are somewhat inconsistent with each other. The last is interesting but lacks confirmation.

Aristotle admitted the superiority of general over particular ideas, and thought that the former corresponded to some specially important part of objects called the 'essence.'

This is nearer the truth. The essence of an object is that part of it, which being present, a given sentimental result follows, or may be expected to follow, or may be made to follow. A certain experience of things is necessary before we can know what is the objective minimum consistent with some sentimental utility. If things are classified with due regard to their utilities, the essence will be the same as the general idea. It is however not true that the essence or any other part of the object causes the sentimental effect (VII).

A common form of the generalistic superstition is to suppose that a thing is explained or sufficiently accounted for by classifying it.

In all philosophies of Greek derivation—the Asiatic [pg 60] seem to be free from this defect—reason is considered to be 'the bringing of a thing under a class-notion,' and when this is done we are supposed to know the thing completely. An elaborate and utterly false dialectic has been erected on this foundation.

No doubt our first attempt at explaining a thing is to refer it to a general idea—to classify it. This usually suggests something to add to the bare phenomenon by way of explanation or hypothesis. But only if we have a prior knowledge of the general idea, derived from things better known than the present phenomenon. The general idea is simply a short formula of that prior knowledge. Suppose we thoroughly know a body of similar things a, b, c, and also reduce them to the general image X; then on seeing d and noticing that it is like a, b, c, we briefly think, 'Oh, it is X,' which excuses us from studying it further. We at once transfer to d our whole knowledge of a, b, c, and in this ideal transfer the explanation consists—not in the classification. The transfer is often tacit—if explicit it is an 'argument.'

If there has been no better known a, b, c, it is evident that the mere generalisation of new facts d, e, f, will not add anything to our knowledge of them. In deduction we should only return to them the knowledge just extracted from them. We should [pg 61] be explaining things by themselves—reasoning in a circle12.

The unity, which explains is not the general idea. It is a unity of function or service, and may include things utterly heterogeneous, and therefore incapable of being reduced to a common idea. The pen in my hand consists of wood and metal; if I generalise them into Matter—the nearest class that includes both—I do not thereby explain the pen. But it is explained by the unity of service: the wood and metal contribute to form one instrument for writing.