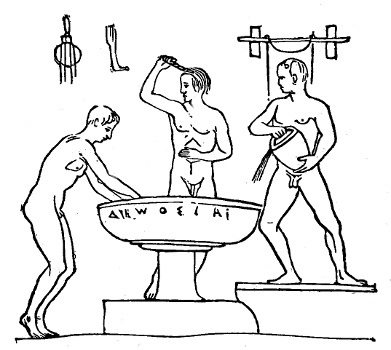

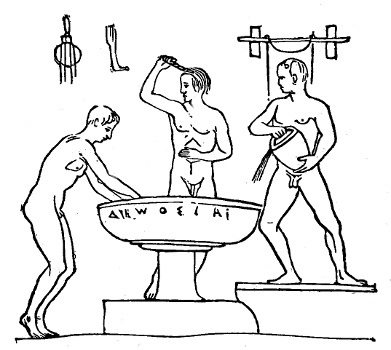

The Greek Bath.—From Sir. Wm. Hamilton’s

vases, in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman

Antiquities; article “Balneæ.”

The footnotes have been re-sequenced for uniqueness across the text, and moved to the end of the text. Links are provided for convenience of navigation

Errors, when reasonably attributable to the printer, have been corrected. The corrections appear as underlined text. The original text will be shown when the mouse is over the word. Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details.

Errors, when reasonably attributable to the printer, have been corrected. The corrections are hyperlinked to an explanatory entry in a transcriber’s note. That note also includes the approach taken for addressing these issues.

“He shall baptize you with the Holy Ghost and with fire.”—Matt. iii, 17.

“This is that which was spoken by the prophet Joel: And it shall come to pass, in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh.”—Acts ii, 16, 17.

Not only does the ordinance of baptism hold a position of pre-eminent honor, as being the door of entrance to all the privileges of the visible church, but it has been distinguished with a place of paramount importance and conspicuity in the transactions of the two grandest occasions in the history of that church,—in sealing the covenant at Sinai, by which Israel became the church of God, and the grace of Pentecost, by which the doors of that church were thrown open to the world. Proportionally interesting and significant is the ordinance, in itself, as symbolizing the most lofty, attractive and precious conceptions of the gospel, and unfolding a history of the plan of God in proportions of unspeakable interest, grandeur and glory. And yet, heretofore, the discussion of the subject has been little more than a disputation, alike uninteresting, inconclusive and unprofitable, concerning the word baptizo.

The present treatise is an attempt to lift the subject out of the low rut in which it has thus traversed, and to render its investigation the means of enlightening the minds and filling the hearts of God’s people with those conceptions, at once exalted and profound, and those high hopes and bright anticipations of the future which the ordinance was designed and so happily fitted to induce and stimulate.

Eighteen years ago,—in a catechetical treatise on “The Church of God, its Constitution and Order,” 4from the press of the Presbyterian Board of Publication,—the author enunciated the essential principles which are developed in this volume. In 1870, they were further illustrated in a tract on “The Bible History of Baptism,” which was issued by the Presbyterian Committee of Publication, in Richmond, Va. The reception accorded to these treatises has encouraged me to undertake the more elaborate disquisitions of the present work. The questions are sometimes such as require a critical study of the inspired originals of the holy Scriptures; and occasional illustrations are drawn from classic and other kindred sources. It has been my study so to conduct these investigations that while they should not be unworthy the attention of scholars, they may be intelligible to readers who are conversant with no other than our common English tongue, the richest and noblest ever spoken by man.

The circumstances and manner of the introduction of the rite of immersion into the post-apostolic church presented a rich and inviting field of further investigation. But the volume has already exceeded the intended limit; the Biblical question is in itself complete, and its authority is conclusive. To it, therefore, the present inquiry is confined.

The fruit of much and assiduous investigation and thoughtful study is now reverently dedicated to the glory of the baptizing office of the Lord Jesus. May he speedily arise and display it in new and transcendent energy; pouring upon his blood-bought church the Spirit of grace and consecration, of knowledge and aggressive zeal, of unity and power; baptizing the nations with his Spirit, and filling the world with the joy of his salvation and the light of his glory.

Covington, Ky., Feb. 8, 1882.

| INTRODUCTION, | Page 15 |

| Book I. | |

| OLD TESTAMENT HISTORY. | |

| Part I. | |

| BAPTISM AT SINAI. | |

| Section I. Baptism originated in the Old Testament.—It was familiar to the Jews when Christ came. There were “divers baptisms” imposed at Sinai, | 21 |

| Section II. No Immersions in the Old Testament.—None in the ritual. None in the figurative language, | 23 |

| Section III. The Old Testament Sacraments.—1. Sacrifice. 2. Circumcision. 3. The Passover. 4. Baptism, | 24 |

| Section IV. The Baptism of Israel at Sinai.--Scene at the mount. The covenant proposed and accepted. A great revival. Baptism of the converts. The feast of the covenant, | 25 |

| Section V. The Blood of Sprinkling.—It was a type of Christ’s atonement, | 30 |

| Section VI. The Living water.—A type of the Spirit. Living and salt water. The river of Eden. That of the Revelation and of the prophets. The Dead Sea. Rain and fountains. Their symbolic functions, | 31 |

| Part II. | |

| THE VISIBLE CHURCH. | |

| Section VII. The Abrahamic Covenant.—It was the betrothal,—not the marriage. Its terms spiritual, everlasting, exclusive. The Seed Christ. It adumbrated the covenant of grace. No salvation but on its terms, | 37 |

| Section VIII. The Sinai Covenant.—Its Conditions.—Moses’ commission. 1. “If ye will obey.” 2. “And keep my covenant,” | 42 |

| Section IX. The Sinai Covenant.—Its Promises.—1. A peculiar treasure. 2. “All the earth is mine.” 3. A priest kingdom. 4. A holy nation. 5. Palestine, | 45 |

| 6Section X. The Visible Church Established.—The Church defined. Its name. Its fundamental law. Membership. Family and eldership. Ordinances of testimony. The relation of the ritual law, | 49 |

| Section XI. The Terms of Membership.—Professed faith and obedience. The same to Israel and Gentiles. Separating the unworthy, | 56 |

| Section XII. Circumcision and Baptism.—The former sealed the Abrahamic covenant. The latter alone sealed the ecclesiastical covenant of Sinai, | 58 |

| Part III. | |

| ADMINISTERED BAPTISMS=SPRINKLINGS. | |

| Section XIII. Unclean Seven Days.—The meaning. Childbirth. Issues. Contact with the dead. Leprosy. Characterized by (1) inward corruption; (2) seven days continuance; (3) contagiousness; (4) requiring sacrifice and sprinkling, | 60 |

| Section XIV.—Baptism of a Healed Leper.—Seven sprinklings. The self-washings. Meaning of the rites, | 66 |

| Section XV. Baptism of the Defiled by the Dead.—The ordinary seal of the covenant. The ashes. Manner of the baptism, | 68 |

| Section XVI. Baptism from Issues.—The law seemingly incongruous. The water of nidda, | 69 |

| Section XVII. Baptism of Proselytes.—Talmudic traditions. Question between the Schools of Shammai and Hillel. The Levitical mode exemplified in the daughters of Midian, | 76 |

| Section XVIII. Baptism of Infants.—The principle of infant membership recognized. Evidence of the baptism of Hebrew children. Example of the infant Jesus, | 82 |

| Section XIX. Baptism of the Levites.—Sprinkled with “water of purifying,” | 85 |

| Section XX. These all were one Baptism. The rites were essentially the same. Slight differences explained, | 86 |

| Section XXI. The Symbol of Rain.—Descent from heaven. Life and fruitfulness imparted. Testimonies of the prophets. Carson’s doctrine, | 88 |

| Section XXII. It meant, Life to the Dead.—Men dead by nature. The Spirit shed down gives life to soul and body. Jesus at the grave of Lazarus, | 92 |

| 7Section XXIII. The Gospel in this Baptism.—(1) The red heifer. (2) Without the camp. (3) Blood sprinkled, and blood and water. (4) Seven times. (5) Seven days’ defilement. (6) The ashes. (7) The water. (8) The sprinkling. (9) The third day and the seventh. (10) The self-washing. (11) Things defiled and sprinkled, | 95 |

| Section XXIV. These were the “Divers Baptisms,”—The argument of Heb. ix, 8, 9. The sprinklings were the theme of Paul’s argument. They were his “divers baptisms,” | 103 |

| Part IV. | |

| RITUAL SELF-WASHINGS. | |

| Section XXV. Unclean until the Even.—From expiatory rites. From contact with the unclean. Self-washing, | 108 |

| Section XXVI. Grades of Self-washing.—1. The hands. 2. The hands and feet. 3. The clothes. 4. The clothes and flesh. 5. Shaving the hair, | 111 |

| Section XXVII. Mode implied in the meaning.—The self-washings meant the active putting off of the sins of the flesh, | 115 |

| Section XXVIII. The words used to designate the Washings.—1. Shātaph. 2. Kābas. 3. Rāhatz, | 116 |

| Section XXIX. Mode of Domestic Ablution.—By water poured on. The patriarchs. Mode in Egypt. In the wilderness. Story of Susanna. Purgation of a concealed murder. Washing the feet at table, | 119 |

| Section XXX. Facilities requisite.—The water drawn from wells by women. No vessels for immersion. The bath of Ulysses, | 126 |

| Section XXXI. The Washings of the Priests.—Symbolism of the tabernacle. The laver. Priestly washings. The laver and river of Ezekiel. No immersions here, | 128 |

| Section XXXII. Like these were the Self-washings of the People.—Designations and meaning the same. Immersion would have been without meaning, | 134 |

| Section XXXIII. Purifyings of things.—One case of immersion. Minor defilements cleansed by this immersion and by washings. The major, by sprinkling, | 136 |

| Part V. | |

| LATER TRACES OF THE SPRINKLED BAPTISMS. | |

| Section XXXIV. Old Testament Allusions.—The rite everywhere, from Moses to Zechariah, | 139 |

| Section XXXV. Rabbinic Traditions.—One heifer from Moses to Ezra. Eight thence to the end, | 142 |

| 8Section XXXVI. Festival of the Outpouring of Water.—Feast of tabernacles. The outpouring. The festivity. Its meaning, | 143 |

| Section XXXVII. Hellenistic Greek.—Alexander’s favor to the Jews. Alexandria. Hellenistic Greek. Its literature. Baptizo. Dr. Conant’s definitions. Baptisma and baptismoi, | 151 |

| Section XXXVIII. Baptism of Naaman. Tābal=baptizo.—The law of leprosy. Office of Elijah and Elisha. Naaman was sprinkled seven times, according to the law, | 157 |

| Section XXXIX. “Baptized from the Dead.”—Ecclus. xxxi, 30. The water of separation here called baptism. “Baptized for the dead.”—1 Cor. xv, 29, | 169 |

| Section XL. Judith’s Baptism.—Story of Judith. Her baptism. Mohammedan washing before prayer, | 172 |

| Section XLI. The Water of Separation in Philo and Josephus.—Philo on the subject. Josephus’ description, | 175 |

| Section XLII. Imitations by the Greeks and Romans.—Diffusive influence of Israel. The stain of crime, and purgation for it, novelties in Greece. Purifying always by sprinkled water. Ovid and Virgil. The Greek mysteries, | 178 |

| Section XLIII. Baptism in Egypt and among the Aztecs.—The libation vase of Osor-Ur. Aztec infant baptism, | 189 |

| Section XLIV. Levitical Baptism in the Fathers.—Tertullian on the idolatrous imitations. Other fathers on the water of separation. They recognize it as baptism, | 192 |

| Part VI. | |

| STATE OF THE OLD TESTAMENT ARGUMENT. | |

| Section XLV. Points established by the foregoing Evidence.—Twenty-one points of evidence enumerated, | 196 |

| Book II. | |

| NEW TESTAMENT HISTORY. | |

| Part VII. | |

| INTRODUCTORY. | |

| Section XLVI. State of the Question.—1. Baptism by sprinkling,—fifteen centuries old,—the Jewish Scriptures full of it,—the Jewish mind molded by it. 2. Immersion,—new,—incongruous,—unmeaning. Carson’s double symbolism, | 201 |

| 9Part VIII. | |

| THE PURIFYINGS OF THE JEWS. | |

| Section XLVII. Accounts in the Gospels.—Purifying before the feasts. The marriage in Cana. Washings and baptisms, | 208 |

| Section XLVIII. Washing Hands before Meals.—Origin of the rite. The marriage feast, | 210 |

| Section XLIX. Baptism on return from Market.—Market defined. Jesus at the Pharisee’s table, | 214 |

| Section L. A Various Reading.—Baptizōntai and rantizōntai. Care taken in transcribing the New Testament. These two readings, | 216 |

| Section LI. Baptisms of Utensils and Furniture.—Their prototypes in the Levitical purifyings of things, | 219 |

| Part IX. | |

| JOHN’s$1BAPTISM. | |

| Section LII. History of John’s Mission.—The accounts of it. John the herald of the Angel of the Sinai covenant, | 221 |

| Section LIII. Israel at the time of John’s Coming.—No longer idolatrous, but apostate. Prophetic warnings. They were excommunicate from the covenant, | 225 |

| Section LIV. Nature of John’s Baptism.—Elijah the champion of the covenant, to the ten tribes. John the same to the Jews. His baptism renewed the Sinai seal, | 228 |

| Section LV. Extent of John’s Baptism.—Testimony of the evangelists. Other evidence. A great revival, | 232 |

| Section LVI. John did not Immerse.—The circumstances forbade it. It would have been unmeaning, | 237 |

| Section LVII. John sprinkled with unmingled Water.—Why the prophecies speak of water only. “The kingdom” John’s theme. Hence, water only. It was sprinkled. Some may have stood in the water, | 241 |

| Part X. | |

| CHRIST’s$1BAPTISMS AND ANOINTING. | |

| Section LVIII. His Baptism by John.—Various explanations. It was part of his obedience. It sealed him Surety of the covenant, and certified to him triumph in his resurrection, | 247 |

| 10Section LIX. His Anointing.—The Spirit given him, at his birth,—at his baptism,—and at his coronation. Meaning and purpose of his anointing, | 254 |

| Section LX. “The Baptism that I am Baptized with.”—Matt. xx, 20-22. The kingdom was to be after the resurrection; and upon condition of being worthy. “The regeneration” was typified by the Levitical baptisms. The baptism was his resurrection. Luke xii, 50, | 257 |

| Part XI. | |

| CHRIST THE GREAT BAPTIZER. | |

| Section LXI. The Kingdom of the Son of man.—“The kingdom of heaven.” Destined to man at creation. Satan’s scheme. The kingdom in the prophets. John’s proclamation. Christ’s triumph and coronation, | 267 |

| Section LXII. Christ is enthroned as Baptizer.—His commission,—to purge the universe. Order of precedence in the Godhead. On earth, Jesus was “in the Spirit.” On the throne, the Spirit is in and subject to him. “The promise of the Father,” | 273 |

| Section LXIII. Note on the Procession of the Spirit.—History of the filioque clause. Objections to it, | 281 |

| Section LXIV. The Baptism of Fire.—The Holy Ghost, and fire, two several things. Fire means wrath. The places cited against this view. The contrasted language of the evangelists. Grace and wrath inseparably connected. John’s theme and imagery are from Malachi. Arguments to identify the two baptisms in one. Baptizo. Mode of the baptism of fire, | 284 |

| Section LXV. The Baptism of Pentecost.—The apostles must “wait for the promise.” The Spirit poured out, | 297 |

| Section LXVI. Manner of the Baptism.—Pnoē,—a breath. Pheromenē,—borne forward,—impelled. “He breathed on them.” It was affusion, signalizing the height where Jesus sits, | 299 |

| Section LXVII. The New Spirit imparted.—The Spirit no novelty. Peter’s explanation. Hitherto, the church’s office was conservative. Now the aggressive Spirit of missions given, | 304 |

| Section LXVIII. The Tongues like as of Fire.—Not “cloven,” but “distributed.” Like the flame of a lamp. The candlestick. The seven stars. “Arise! shine!” | 310 |

| Section LXIX. The Gift of other Tongues.—Signified the union of all people in God’s worship. The phrasing of the historian. History of the sign, | 313 |

| 11Section LXX. The Baptism of Repentance.—The firstfruits. John’s “baptism of repentance.” Jesus gives repentance and remission. His baptism unites to him and the Father. Its manner. The Spirit’s relation to it, | 318 |

| Section LXXI. Paul’s Doctrine of this Baptism.—Titus iii, 4-7. Meaning of loutron. 1 Cor. xii, 12-14. Eph. iv, 4-16. Gal. iii, 27-29. Rom. vi, 2-6. Col. ii, 9-11. The doctrine of these places, | 323 |

| Section LXXII. Noah “saved by Water.”—1 Pet. iii, 17-22. Peter and Paul. The theme,—the saints persecuted with impunity. Noah persecuted, and saved by means of the flood. Christ’s people saved by antitype baptism, | 333 |

| Section LXXIII. Christ’s Baptizing Administration.—It covers his whole work on the throne. In the end, triumph complete, physical and moral. When he shall have purged earth and heaven, then will his baptizing office cease, | 338 |

| Section LXXIV. Argument from the Real to Ritual Baptism.—The real baptism has to do, not with abasement and the grave, but with exaltation and power. But immersion looks only to the grave. It is incongruous to all the phenomena of Pentecost. Immersed in “the sound from heaven,” | 343 |

| Part XII. | |

| THE BAPTIST ARGUMENT. | |

| Section LXXV. Baptizo and the Resurrection.—Elements of the Baptist argument. Dr. Conant on baptizo. It leaves its subjects in the water. Dr. Kendrick’s admissions. A second meaning in baptizo, | 347 |

| Section LXXVI. The Prepositions.—En. Eis. Ek. Apo. They indicate, not the mode, but the place of the baptisms, | 354 |

| Section LXXVII. “Much Water there.”—Aenon=The Springs. Many waters. Why Jesus and John resorted to waters, | 360 |

| Section LXXVIII. “Buried with him by Baptism into Death.”—Rom. vi, 2-7.—“Buried with him by the baptism into the death.” Analysis of the passage. Spiritual baptism alone referred to. Immersion incongruous to Paul’s conception, | 364 |

| Section LXXIX. “Buried with him in Baptism.”—Col. ii, 9-13. The doctrine the same as the preceding. Union with the Lord Jesus the controlling idea. “Buried with him in (or, by) the baptism.” The idea of immersion perplexes the exegesis, | 371 |

| 12Section LXXX. End of the Baptist Argument.—Baptist scholars concede that baptizo does not mean, to dip, only. It can not then decide the mode. They admit that it leaves its subject in the water. It knows then nothing of the resurrection. The prepositions and waters of Enon do not help the cause. Paul’s burial “in the baptism,” does not allude to the ritual ordinance. In all its parts, the argument fails, | 374 |

| Part XIII. | |

| BAPTISMAL REGENERATION. | |

| Section LXXXI. Contrary to the whole Tenor of the Gospel.—The mystery of iniquity early developed. The gospel church viewed as the antitype of the Levitical. The Scriptures are not so. Treatment of baptism by the evangelists. Paul’s testimony, | 377 |

| Section LXXXII. Born of Water and of the Spirit.—John iii, 4-8. Metaphor of water. “Water even the Spirit.” John had already stated the way of the new birth, | 384 |

| Section LXXXIII. “The Washing of Water, by the Word.”—The bridal bath. No formula of baptism. “Sanctify them through thy truth,” | 390 |

| Part XIV. | |

| THE NEW TESTAMENT CHURCH. | |

| Section LXXXIV. The Ritual Law is unrepealed.—Christ so left it. The apostles were zealous for it. The council of Jerusalem exempted the Gentiles only. James and Paul unite to show it still in force. Paul’s practice. He obeyed the law, but repudiated its righteousness. This view alone harmonizes the history, | 393 |

| Section LXXXV. Why the Gentiles were exempted.—Not because the law expired. But, unsuited to a world wide extension. Its chief end accomplished. What its survival implied, | 406 |

| Section LXXXVI. The Christian Passover.—Wine, and blood. The passover a type of Christ’s atonement. It is perpetuated in the Supper, | 408 |

| Section LXXXVII. The Hebrew Christian Church.—The synagogue system. The sects of Pharisees, Sadducees and Nazarenes. The number and diffusion of the Nazarenes. The Hebrew church after the destruction of Jerusalem, | 411 |

| 13Section LXXXVIII. The Gentiles Graffed in.—Mixed churches. Gentile churches. “Out of Zion the law.” The Gentiles graffed in, | 418 |

| Part XV. | |

| CHRISTIAN BAPTISM. | |

| Section LXXXIX. History of the Rite.—The cotemporaneous baptisms of John and Jesus. Both were the same Christian baptism. Christ did not institute baptism, but gave it to the Gentiles. Rebaptism at Ephesus. Note on rebaptism, | 424 |

| Section XC. “Baptizing them into the Name.”—1. Into the name. En; epi; eis. “Into Christ.” “Into the name of Christ.” 2. “The name of the Father and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.”—“The name of the Lord Jesus,” | 431 |

| Section XCI. “He that Believeth and is Baptized.”—It refers to ritual baptism; and is a caution against trust in it. Faith is the essential thing, | 437 |

| Section XCII. The Formula.—Ritualistic view. No formula prescribed by Christ, nor used by the apostles, | 438 |

| Section XCIII. The Administration on Pentecost.—There was a baptism with water. Dr. Dale’s objections, | 440 |

| Section XCIV. The meaning of this Baptism.—It could but symbolize the baptism of the Spirit. The two formulas thus reconciled, | 446 |

| Section XCV. The Mode of this Baptism.—Immersion incongruous and impossible. They were baptized in groups with a hyssop bush, | 448 |

| Section XCVI. Other Illustrations.—The eunuch. The apostle Paul. The house of Cornelius. The jailer. None of these look to immersion, | 451 |

| Section XCVII. “Baptized into Moses.”—Moses and Israel were types. Dr. Kendrick contradicts the record. By this baptism Israel were brought into a new state of faith and obedience, | 457 |

| Part XVI. | |

| THE FAMILY AND THE CHILDREN. | |

| 14Section XCVIII. Christ and the Children.—A retrospect. Christ’s attitude toward the lambs. Peter’s commission. The Jews predominant in the church. The Sinai covenant recognized the children and made place for the Gentiles, | 461 |

| Section XCIX. “Now are they Holy.”—Unclean, and holy. Israel a holy nation. “The saints.” The Baptist exegesis of the language, | 466 |

| Section C. Household Baptisms.—Not “infant,” but “family baptism.” Lydia’s house. The jailer and all his. The house of Stephanas. These, in the light of fifteen centuries preceding, and of the everlasting covenant, | 471 |

| Conclusion. | |

| Christ’s real baptism with the Spirit is the criterion of all baptismal doctrines and rites. Baptismal regeneration tried and rejected. The evidence against immersion cumulative and overwhelming, | 476 |

The history of the ritual ordinances of God’s appointment is full of painful interest. Passing any reference to the times preceding the transactions of Sinai,—the institutions then given to Israel constituted a system of transparent, significance, perfect in the congruous symmetry and simplicity of the parts and comprehensive fullness of the whole, as setting forth the whole doctrine of God concerning man’s sin and salvation. Designed not only for the instruction of Israel, but for a light to the darkness of the surrounding Gentile world, its truths were embodied in symbols which spake to every people of every tongue in their own language. Copied in imperfect and perverted forms into the rites of Gentile idolatry,—although distorted, veiled and dislocated from their normal relations, they shed gleams of twilight into the gloom of spiritual darkness, and prepared the world for the dawning of the Sun of Righteousness, when he rose upon the nations. To multitudes of Israel, those ordinances were efficient means of eminent grace. With gladness, they saw therein,—as through a glass, darkly, it may be, but surely,—adumbrations of the salvation, grace and glory of the Messiah’s kingdom. And, if the fact be considered that at one of the darkest crises in Israel’s history, when the prophet cried,—“I, even I am left alone,”—God could assure him,—“Yet have I left seven thousand,”—we may possibly find occasion to revise our preconceptions concerning the history of the gospel in Israel. Still, undoubtedly there were multitudes in every generation of that people to whom the gospel preached in the ordinances brought no profit, for lack of faith. In their earlier history, indifference and neglect, and in the later, a self-righteous zeal for the mere outward rites and forms, were equally fatal. The splendor of the ritual, and the superfluous variety and frequency of the observances, were a poor substitute for faith toward God, and rectitude of heart and life. The result was that when Christ came, who was the end of all the rites and ordinances of the law, those who were the most strict and zealous in their observance were his betrayers and murderers.

When the Lord Jesus ascended the heavens, assumed the throne, and sent forth the gospel to the Gentiles, it was accompanied by two simple ordinances, which were eliminated out of those of the Levitical 16ritual, by the omission of the element of sacrifice. In them was symbolized and set forth the whole riches of that salvation which was represented in the more cumbrous forms of the Levitical system. By the supper, was signified the mystery of his atoning sufferings, and of the nourishment of his people by faith therein. By baptism, was shown forth the glory of his exaltation, and the sovereignty and power with which he sheds from his throne the blessings of his grace. But very soon, these ordinances, so beautiful and instructive in their simplicity, were corrupted through the misconceptions and ignorance of the teachers of the church. The Mosaic ritual, instead of being recognized, as Paul describes it, as a pattern or similitude of the things in the heavens, was regarded as a type of the New Testament church and of the ordinances therein administered. This one error became the inevitable cause of corruption and apostasy. Respecting the impending defection, Paul assured the Thessalonians, that the mystery of iniquity was already at work; and forewarned the elders of Ephesus of the coming of grievous wolves to rend the flock, and of apostasies among themselves, through the lust of an unhallowed ambition.

We have not the means, from the scanty and corrupted records which remain, of the age immediately following the apostles, of tracing the process of defection. But when, at length, the church emerges into the light of history, it is found to have realized a fatal transformation. The pastors and elders of the apostolic churches, from being simple preachers of the word, have become priests ministering at the altar, and offering better sacrifices than those made by the Aaronic line. For, while the latter offered mere animals, and the worshippers fed upon mere carnal food, the former, in the sacrament of the supper, the supposed antitype of those offerings, were believed to offer the body and blood of the Lord Jesus, and the people, in those elements, imagined themselves to receive and feed upon that very body and blood. So, too, while the “type baptisms” of the ancient ritual accomplished a mere purifying of the flesh, the baptism of water by the hands of the Christian ministry was regarded as the antitype of these, and considered effectual for accomplishing a spiritual regeneration, a renewing of the heart of the recipient.

The same error which thus corrupted the doctrine of the sacraments, was equally efficient in changing their forms. As they were held to be the antitypes of the Old Testament rites, it was sought to develop in them features to correspond with all the details of those rites, and to give them a dignity, a pomp and ceremonial, proportioned to their relations as fulfilling the things set forth in the splendid ritual of Moses and David. The rite of baptism, particularly, was corrupted by alterations and additions which left scarcely 17any thing of the primitive institution, save the name. The Levitical purifyings were especially observed in connection with the annual feasts at Jerusalem. In like manner, the administration of baptism was discouraged, except in connection with two of those feasts,—the passover, and the feast of weeks, or of firstfruits,—transferred into the Christian church, under the names of Easter, and Pentecost, or Whitsunday; the latter being named from the white garments in which the newly baptized were robed. The administration was connected with an elaborate system of attendant observances. First, was a course of fastings, genuflections, and prayers, and the imposition of hands upon the candidate. Then, he was divested of all but a single under garment, and facing the west, the realm of darkness, was required, with defiant gesture of the hand, to renounce Satan and all his works. This was followed by an exorcism, the minister breathing upon the candidate, for expelling Satan, and imparting the Holy Spirit; then the making upon him of the sign of the cross; anointing him with oil, once before and once after the baptism; the administration of salt, milk and honey, and three immersions, one at the name of each person of the Trinity. Such was the connection in which baptism by immersion first appears. For its reception, the candidate, of whatever sex, was invariably divested of all clothing, and, after it, was robed in a white garment, emblematic of the spotless purity now attained. The rite of baptism by bare sprinkling, however, still survived. And the question is entitled to a critical attention which it has not yet received, whether, always or generally, the more elaborate rite consisted in a submersion of the candidate. Against this supposition, is the practice of the Abyssinian, Greek, Nestorian and other churches of the east. In them, the candidate, in preparation for the rite, is placed, or we may say, immersed, naked, in a font of water, the quantity of which neither suffices, nor is intended, to cover him. The administrator then performs the baptism, while pronouncing the formula, by thrice pouring water on the candidate, once at the mention of each name of the blessed Godhead.[1] To the same effect, is the evidence of numerous remains of Christian art, which have been transmitted to us from the early ages. Among these are several representations of the baptism of the Lord Jesus by John; one, of that of Constantine and his wife, by Eusebius; and others. The baptism of Constantine precisely corresponds with the description above given. The emperor 18is seated naked in a vessel, which if full would not reach to his waist; and the bishop is in the act of performing the baptism by pouring water upon them. In the representations of the baptism of Jesus, he sometimes appears waist-deep in the Jordan, and sometimes on the land. But in all cases, the rite is performed by the baptist pouring water on his head out of a cup or shell. Such is, in fact, the invariable mode represented in these remains of ancient art.

In this connection the analogy of the forms of religious purifying prevalent throughout the east is worthy of special notice. The Brahmin, before taking his morning’s meal, repairs to the Ganges, carrying with him a brazen vessel. By hundreds, or by thousands, they enter the stream, and while some take up the water in their vessels, and pour it over their persons, others plunge beneath the stream, for the purging away of their sins. Then filling the vessels, they repair to the temple, and pour the water upon the idol, or as a libation, before it. The Parsee, worshiper of the sun, goes, in the morning, to river or sea, and entering until the waves are waist high, with his face toward the east, awaits the rising of the sun, when, using his joined hands as a dipper, he dashes water over his person, and makes obeisance to his god. On the other hand, the Mohammedan, deriving his usage from the earlier Pharisaic ritual, repairs to the mosque, and from the tank in front, without entering it, takes up water in his hands with which to bathe face, feet and hands, before presenting his prayers.

By the corruptions in the Christian church, before exemplified, the key of knowledge was taken away from the people. The instructive meaning of the sacraments was obscured and obliterated, by the idea of their intrinsic efficacy for renewing the heart and atoning for and purging sin. The preaching of the word was disparaged and ultimately set aside; the preachers having become propitiating priests, working regeneration by the baptismal rite, and making atonement by the sacrifice of the mass. The corruption and tyranny of the clergy of the middle ages, and the ignorance, slavery and spiritual darkness which for centuries brooded over the people, were the inevitable results.

The reformation came, through the recovery by Luther of the golden doctrine of justification by faith, which had so long been buried and lost under the accumulated mass of ritualistic error. But even Luther was unable to shake off the fetters of superstition and falsehood in which he had been cradled, and to enjoy the full liberty of the doctrine which he gave to the awakened church. In the dogma of consubstantiation, he transmitted to his followers the very error which had corrupted the church for more than a thousand years. And the result in the churches of his confession has added another 19to the already abundant evidence of the ever active and irreconcilable antagonism which exists between the theory of sacramental grace, and the doctrine,—criterion of a standing or falling church,—of justification by free grace through faith.

Our space does not admit of a critical tracing of the history of the sacramental question in the churches of the reformation. On the one hand, ritualists of every grade, misled by the erring primitive church, and attributing to the sacraments a saving virtue intrinsic in them, render indeed high but mistaken honor to the sacred rites; but fail to enjoy them in their true intent and office, or to view and honor them in their proper character. On the other hand, our immersionist brethren, misguided respecting the form of baptism, by the same erring example, and thus lost to the true and comprehensive meaning of the ordinance, have failed to apprehend the instruction which it was designed to impart, and to enjoy the abundant edifying which it was adapted to minister; and, instead, have found it a potent agent of separation, and an efficient temptation to the indulgence of a disproportionate zeal on behalf of mere outward rites and forms.

Nor do those who have escaped these errors always seem to appreciate the sacraments, in their true design and character, as ever active and efficient witnesses, testifying to the gospel, through symbols as intelligible and impressive as the most eloquent speech. The beauty and rich significance of the supper have, indeed, been in a measure apprehended, and made available in some just proportion, to the instruction and edifying of God’s people. But baptism has not held the place, in the ministrations of the sanctuary and the mind of the church, which is due to its office and design, to the richness of meaning of its forms, and to the sublime conceptions and the lofty aspirations and hopes which it is so wonderfully adapted to create and cherish. One efficient cause of this, undoubtedly, is, the reaction induced by the aggressive zeal of immersionists, and the exercise of a false charity toward their erroneous sentiments; as though the charity of the gospel, as toward our brethren, consisted in an acceptance of their errors as equivalents to the truths of God. While they have justly and irrefragably maintained that nothing can be Christian baptism which has not at once the form and the meaning ordained by Christ, we have been weakly disposed to imagine ourselves patterns of charity, in admitting the validity of immersion, while denying it to be the form or to have the meaning which Christ ordained. As if such an ordinance, from the great Head of the Church, could have in it any thing indifferent, or subject to our discretion, whether in doctrine or mode! The immediate and inevitable result is, a low estimate of the ordinance itself; indifference alike to its form and meaning, and to the place it was designed to fill, and 20the offices which it was to perform, in the economy of grace. As a mere door of entrance into the fold of the church, it is administered and received; with too little regard to its beautiful and comprehensive symbolism; and, once performed, it is almost lost sight of in the instructions of the pulpit, and meditations of the people. Should this representation suggest a doubt, let the reader reflect how often, in the ordinary ministrations of the sanctuary, he has heard the significance of baptism dwelt upon, or even alluded to, for illustrating the great truths of the gospel, on any occasion except that of the administration of the rite; and how seldom, even then, the richness of its symbolic import is unfolded,—its relations to Christ’s exaltation and throne, and to all the functions of his scepter; the meaning of the element of water, and of the mode of sprinkling; and the office of the ordinance, as a symbol of the Spirit’s renewing grace, and a prophecy and seal to the doctrine of the resurrection. As the initial seal of the covenant, it is discussed and insisted upon. But of these, its intrinsic and most interesting characteristics, but little is heard. No wonder, therefore, that the privilege of its reception is so little appreciated, and its appropriation by parents on behalf of their children, so often neglected.

The recent researches of Drs. Conant and Dale have exhausted the philological argument as concerning baptizo. The former, representing the American (Baptist) Bible Union, and the latter, from the opposite standpoint, have come to conclusions which, to all the practical purposes of the discussion, are identical and final. Essentially, they agree (1) that baptizo never means, to dip, that is, to put into the water and take out again; but, primarily, to put into or under the water,—to bring into a state of mersion, or intusposition; (2) that it also means to bring into a new state or condition, by the exercise of a pervasive control; as one who is intoxicated is said to be baptized with wine. The former of these meanings is all that remains to the Baptist argument from the word. The latter is all that is desired by those who repudiate immersion. The philological discussion being thus brought to a practical termination, the occasion seems opportune for inviting attention to the real issues involved in the question respecting the form of the ordinance; and to the various and abundant testimonies of the Scriptures, as to its origin and office, its mode and meaning, its history and associations.

In the same line of investigation, it is the expectation of the writer, should time and opportunity concur, to offer to the Christian public, at some future day, a treatise, similar in plan to that now presented, on the ordinances and church of God, historically traced from the apostasy, and the renewal of the covenant in Eden, to the close of the sacred volume.

At the time of Christ’s coming, baptism was a rite already familiar to the Jews. The evangelists testify of them that, “when they come from the market, except they baptize (ean mē baptisōntai) they eat not. And many other things there be which they have received to hold, as the baptisms (baptismous) of cups and pots and brazen vessels and tables.”—Mark vii, 3, 4. On account of this rule of tradition, a Pharisee at whose table Jesus was a guest “marveled that he had not first baptized (ebaptisthē) before dinner.”—Luke xi, 38. Hence, when John came, a priest, baptizing, there was no question raised as to the origin, nature, form, or divine authority of the ordinance which he administered. The Pharisees, in their challenge of him, confine themselves to the single demand, by what authority he ventured to require Israel to come to his baptism, since he confessed that he was neither Christ nor Elias nor that prophet. (John i, 25.) Their familiarity with the rite forbade any question concerning it. Had we no further light on the subject, we might suppose that this ordinance 22had no better source than the unauthorized inventions of Jewish tradition. But the Apostle Paul,[2] an Hebrew of the Hebrews, taught at the feet of Gamaliel, and versed in all questions of the law, excludes such an idea. He declares that in the first tabernacle “were offered both gifts and sacrifices that could not make him that did the service perfect as pertaining to the conscience; which stood only in meats and drinks and (diaphorois baptismois) divers baptisms—carnal ordinances imposed on them until the time of reformation.”—Heb. ix, 9, 10. The conjunction “and” (“divers baptisms and carnal ordinances”) is wanting in the best Greek manuscripts; is rejected by the critical editors, and is undoubtedly spurious. The phrase “carnal ordinances” is not an additional item in the enumeration, but a comprehensive description of “the meats and drinks and divers baptisms” of the law. Paul thus speaks of them by way of contrast with the spiritual grace and righteousness of the Lord Jesus. A critical examination of this passage will be made hereafter. For the present, we note two points as attested by the apostle:

1. Among the Levitical ordinances there were not one but divers baptisms.

2. These were not merely allowable rites, but were “imposed” on Israel as part of the institutions ordained of God at Sinai.

It may be proper to add that they were baptisms of persons, and not of things. They were rites which were designed to purify the flesh of the worshiper. (vs. 9, 13, 14.)

These baptisms were, therefore, well known to Israel, from the days of Moses. This explains the fact that, in the New Testament, we find no instruction as to the form of the ordinance. It was an ancient rite, described in the books of Moses and familiar to the Jews when Christ came. No description, therefore, was requisite. We are then to 23look to the Old Testament to ascertain the form and manner of baptism.

Says Dr. Carson: “We deny that the phrase ‘divers baptisms’ includes the sprinklings. The phrase alludes to the immersion of the different things that by the law were to be immersed.”[3] Had this learned writer pointed out the things that were to be immersed, and the places in the law where this was required, it would have saved us some trouble. In default of such information, our first inquiry in turning to the Old Testament will be for that form of observance. We take up the books of Moses, and examine his instructions as to all the prominent institutions of divine service. But among these we find no immersion of the person. We enter into minuter detail, and study every rule and prescription of the entire system as enjoined on priests, Levites, and people, respectively. But still there is no trace of an ordinance for the immersion of the person or any part of it. We extend our field of inquiry, and search the entire volume of the Old Testament. But the result remains the same. From the first chapter of Genesis to the last of Malachi, there is not to be found a record nor an intimation of such an ordinance imposed on Israel or observed by them at any time. Not only is this true as to baptismal immersion performed by an official administrator upon a recipient subject. It is equally true as to any conceivable form or mode of immersion, self-performed or administered. There is no trace of it. But here is Paul’s testimony that there were “divers baptisms imposed.” By baptisms, then, Paul certainly did not mean immersions.

The impregnable position thus reached is further fortified by the fact that, in all the variety and exuberance of 24figurative language used in the Bible to illustrate the method of God’s grace, no recourse is ever had to the figure of immersion. All agree that the sacraments are significant ordinances. If, then, the significance of baptism at all depends on the immersion of the person in water, we would justly expect to find frequent use of the figure of immersion, as representing the spiritual realities of which baptism is the symbol. But we search the Scriptures in vain for that figure so employed. It never once occurs.

As there are no immersions in the Old Testament, we must look for the divers baptisms under some other form. Assuming that in this rite there must be a sacramental use of water, we will first examine the ancient sacraments. On a careful analysis of the ordinances comprehended in the Levitical system, we find among them four which strictly conform to the definition of a sacrament, and which are the only sacraments described or referred to in the Old Testament.

1. Sacrifice.—The first of these in origin and prominence was sacrifice. Originating in Eden, and incorporated in the Levitical system, it had all the characteristics of a sacrament. In it the life blood of clean animals was shed and sprinkled, and their bodies burned upon the altar. Thus were represented the shedding of Christ’s blood, and his offering of atonement to the justice of God. But here is no water. It is not the baptism for which we seek.

2. Circumcision.—The second of the Old Testament sacraments was circumcision, whereby God sealed to Abraham and his seed the covenant of blessings to them and all nations through the blood of the promised Seed. Here, again, no one will pretend to identify the ordinance with the baptisms of Paul.

3. The Passover.—The third of the Old Testament sacraments, the first of the Levitical dispensation, was the 25feast of the passover. In it, the paschal lamb was slain, its blood sprinkled on the lintels and door posts of the houses, and the flesh roasted and eaten with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. At Sinai, this ordinance was modified by requiring the feast to be observed at the sanctuary, the blood being sprinkled on the altar, and the fat burned thereon. And, to the other elements appointed in Egypt, the general provisions of the Mosaic law added wine. All peace offerings, free will offerings, and offerings at the solemn feasts, of which the passover was one, were to be accompanied with wine, and were eaten by the offerers, except certain parts, that were burned on the altar. (See Num. xv, 5, 7, 10; xxviii, 7, 14.) This ordinance, eliminated of its sacrificial elements, is perpetuated in the Lord’s supper. In it was no water. It was not the rite for which we seek.

4. Baptism.—There remains but one more of the Mosaic sacraments. It was instituted at Sinai. In it, water was essential, and by it was symbolized the renewing agency of the Holy Spirit. It was “a purification for sin,” an initiatory ordinance, by which remission of sins and admission to the benefits of the covenant were signified and sealed to the faith of the recipients. It occupied, under the Old Testament economy, the very position, and had the significance, which belong to Christian baptism under the New. Moreover, it appears under several modifications, and is thus conformed to Paul’s designation of “divers baptisms,” whilst these, in their circumstantial variations, were essentially one and the same ordinance.

The occasion of the first recorded administration of this rite was the reception of Israel into covenant with God at Sinai. For more than two hundred years they had dwelt in Egypt, and for a large part of the time had been bondmen there. The history of their sojourn in the wilderness 26shows that not only was their manhood debased by the bondage, but their souls had been corrupted by the idolatries of the Egyptians (Josh. xxiv, 14; Ezek. xx, 7), and they had forgotten the covenant and forsaken the God of their fathers. They were apostate, and, in Scriptural language, unclean.

But now the fullness of time had come, when the promises made to the fathers must be fulfilled. Leaving the nations to walk after their own ways, God was about to erect to himself a visible throne and kingdom among men, to be a witness for him against the apostasy of the race. He was about to arouse Israel from her debasement and slavery, to establish with her his covenant, and to organize and ordain her his peculiar people—his Church.

Proportioned to the importance of such an occasion was the grandeur of the scene and the gravity of the transactions. Of them we have two accounts, one from the pen of Moses (Ex. xx-xxiv), and the other from the Apostle Paul, in exposition of his statement as to the divers baptisms. (Heb. ix, 18-20.) As to these accounts, two or three points of explanation are necessary. (1) The two words, “covenant” and “testament,” represent but one in the originals in these places, of which “covenant” is the literal meaning. (2) Paul mentions water (Heb. ix, 19), of which Moses does not speak. The fact is significant, as the apostle is in the act of illustrating the “divers baptisms,” of which he had just before spoken. (3) The word “oxen,” in our translation (Ex. xxiv, 5), should be “bulls.” Oxen were not lawful for sacrifice. Yearling animals seem to have been preferred. Says Micah, “Shall I come before the Lord with burnt-offerings, with calves of a year old?”—Micah vi, 6. Hence Paul indifferently calls them bulls and calves. The goats of which he speaks were no doubt among the burnt-offerings of Moses’s narrative. Both “small and great cattle” seem to have been offered on all great national solemnities.

The redeemed tribes came to Sinai in the third month 27after the exodus. Moses was called up into the mount and commanded to propose to them the covenant of God. It was in these terms: “If ye will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then ye shall be a peculiar treasure unto me above all people, for all the earth is mine, and ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”—Ex. xix, 3-6. This proposal the people, with one voice, accepted. God then commanded Moses: “Sanctify the people to-day and to-morrow, and let them wash their clothes and be ready against the third day; for the third day the Lord will come down in the sight of all the people upon Mount Sinai.”—Vs. 10, 11. On the third day, in the morning, there were thunders and lightnings, and a thick cloud upon the mount, and the voice of the trumpet exceeding loud, so that all the people trembled. And Mount Sinai was altogether on a smoke, because the Lord descended upon it in fire, and the smoke thereof ascended as the smoke of a furnace, and the whole mount quaked greatly. And when the voice of the trumpet sounded long, and waxed louder and louder, Moses spake, and God answered him by a voice. And the Lord came down upon the top of the mount; and the Lord called Moses up to the top of the mount, and Moses went up.

In the midst of this tremendous scene, so well calculated to fill the people with awe, and to deter them from the thought of a profane approach, Moses was nevertheless charged to go down and warn the people, and set bounds around the mountain, lest they should break through unto the Lord to gaze, and many of them perish. After such means, used to impress Israel with a profound sense of God’s majesty and their infinite estrangement from him, his voice was heard, uttering in their ears the Ten Commandments, prefaced with the announcement of himself as their God and Redeemer. (Compare Deut. iv, 7-13.) At the entreaty of the people, the terribleness of God’s audible voice was withdrawn, and Moses was sent to tell 28them the words of the Lord and his judgments. The people again unanimously declared, “All the words which the Lord hath said, will we do.”—Ex. xxiv, 3.

In this sublime transaction we have all the scenes and circumstances of a mighty revival of true religion. It is a vast camp-meeting, in which God himself is the preacher, speaking in men’s ears with an audible voice from the top of Sinai, and alternately proclaiming the law of righteousness and the gospel of grace, calling Israel from their idolatries and sins to return unto him, and offering himself as not only the God of their fathers, but their own Deliverer already from the Egyptian bondage, and ready to be their God and portion—to give them at once the earthly Canaan, and to make it a pledge of their ultimate endowment with the heavenly. The people had professed with one accord to turn to God, and pledged themselves, emphatically and repeatedly, to take him as their God, to walk in his statutes and do his will, to be his people.

It is true that, to many, the gospel then preached was of no profit, for lack of faith; whose carcasses therefore fell in the wilderness. (Heb. iii, 17-19; iv, 2.) But it is equally true that the vast majority of the assembly at Sinai were children and generous youth, who had not yet been besotted by the Egyptian bondage. To them that day, which was known in their after history as “the day of the assembly” (Deut. x, 4; xviii, 16), was the beginning of days. Its sublime scenes became in them the spring of a living faith. With honest hearts they laid hold of the covenant, and took the God of the patriarchs for their God. Soon after, the promise of Canaan, forfeited by their rebellious fathers, was transferred to them. (Num. xiv, 28-34.) Trained and disciplined by the forty years’ wandering, it was they who became, through faith, the irresistible host of God, the heroic conquerors and possessors of the land of promise. Centuries afterward, God testified of them that they pleased 29him: “I remember thee, the kindness of thy youth, the love of thine espousals, when thou wentest after me in the wilderness, in a land that was not sown. Israel was holiness to the Lord, and the firstfruits of his increase.”—Jer. ii, 2, 3. Until the day of Pentecost, no day so memorable, no work of grace so mighty, is recorded in the history of God’s dealings with men as that of the assembly at Sinai.

And as on the day of Pentecost the converts were baptized upon their profession of faith, so was it now. Moses appointed the next day for a solemn ratifying of the transaction. He wrote in a book the words of the Lord’s covenant, the Ten Commandments; and in the morning, at the foot of the mount, built an altar of twelve stones, according to the twelve tribes. On it young men designated by him offered burnt-offerings and sacrificed peace-offerings of young bulls. Moses took half the blood and sprinkled it on the altar. Half of it he kept in basins. He then read the covenant from the book, in the audience of all the people, who again accepted it, saying, “All that the Lord hath said will we do, and be obedient.” Moses thereupon took the blood that was in the basins, with water and scarlet wool and hyssop, and sprinkled both the book and all the people, saying, “Behold the blood of the covenant which the Lord hath made with you concerning all these words.”—Ex. xxiv, 8, compared with Heb. ix, 19, 20.

In the morning Moses had already, by divine command, assembled Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel. And no sooner was the covenant finally accepted and sealed with the baptismal rite, than these all went up into the mount, and there celebrated the feast of the covenant. “They saw the God of Israel; and there was under his feet, as it were, a paved work of a sapphire stone, and as it were the body of heaven in his clearness. And upon the nobles of Israel, he laid not his hand. Also, they saw the God of Israel, and did eat 30and drink.”—Ex. xxiv, 1, 9-11. So intimate, privileged, and spiritual was the relation which the covenant established between Israel and God.

Thus was closed this sublime transaction, ever memorable in the history of man and of the church of Christ, in which the invisible God condescended to clothe himself in the majesty of visible glory, to hold audible converse with men, to enter into the bonds of a public and perpetual covenant with them, and to erect them into a kingdom, on the throne of which his presence was revealed in the Shechinah of glory.

Such were the occasion and manner of the first institution and observance of the sacrament of baptism. In its attendant scenes and circumstances, the most august of all God’s displays of his majesty and grace to man; and in its occasion and nature, paramount in importance, and lying at the foundation of the entire administration of grace through Christ. It was the establishing of the visible church.

In all the Sinai transactions, Moses stood as the pre-eminent type of the Lord Jesus Christ; and the rites administered by him were figures of the heavenly realities of Christ’s sacrifice and salvation. This is fully certified by Paul, throughout the epistle to the Hebrews, and especially in the illustration which he gives of his assertion concerning the divers baptisms imposed on Israel. See Heb. ix, 9-14, 19-28. In these places, it distinctly appears that the blood of the Sinai baptism was typical of the atonement of Christ. Not only in this, but in all the Levitical baptisms, as will hereafter appear, blood was necessary to the rite. In fact, it was an essential element in each of the Old Testament sacraments. The one idea of sacrifice was the blood of atonement. The same idea appeared in circumcision, revealing atonement by the blood 31of the seed of Abraham. In the passover the blood of sprinkling was the most conspicuous feature; and in the Sinai baptism blood and water were the essential elements.

Peter states the Old Testament prophets to have “inquired and searched diligently, searching what, or what manner of time the Spirit of Christ which was in them did signify, when it testified beforehand the sufferings of Christ and the glory that should follow.”—1 Pet. i, 10, 11. Of the time and manner they were left in ignorance. But the blood, in all their sacraments, was a lucid symbol, pointing them forward to the sufferings of Christ as the essential and alone argument of the favor and grace of God. In it, and in the rites associated with it, they saw, dimly it may be, but surely, the blessed pledge that in the fullness of time “the Messenger of the covenant” would appear (Mal. iii, 2), magnify the law and make it honorable (Isa. xlii, 21), by his knowledge, justify many, bearing their iniquities (Isa. liii, 11), and sprinkle the mercy-seat in heaven, once for all, with his own precious and effectual blood—the blood of the everlasting covenant. (Heb. ix, 24-26; xiii, 20; 1 Pet. i, 11.)

In the Sinai baptism, as at first administered to all Israel, and in all its subsequent forms, living or running water was an essential element. This everywhere, in the Scriptures of the Old Testament and of the New, is the symbol of the Holy Spirit, in his office as the agent by whom the virtue of Christ’s blood is conveyed to men, and spiritual life bestowed. In the figurative language of the Scriptures, the sea, or great body of salt or dead water, represents the dead mass of fallen and depraved humanity. (Dan. vii, 2, 3; Isa. lvii, 20; Rev. xiii, 1; xvii, 15.) Hence, of the new heavens and new earth which are revealed as the inheritance of God’s people, it is said, “And there shall be no more sea.”—Rev. xxi, 1.

32The particular source of this figure seems to have been that accursed sea of Sodom, which was more impressively familiar to Israel than any other body of salt water, and which has acquired in modern times the appropriate name of the Dead Sea—a name expressive of the fact that its waters destroy alike vegetation on its banks and animal life in its bosom. Its peculiar and instructive position in the figurative system of the Scriptures appears in the prophecy of Ezekiel (xlvii, 8, 9-11), where the river of living water from the temple is described as flowing eastward to the sea; and being brought forth into the sea, the salt waters are healed, so that “there shall be abundance of fish.”

Contrasted with this figure of sea water is that of living water, that is, the fresh water of rain and of fountains and streams. It is the ordinary symbol of the Holy Spirit. (John vii, 37-39.) The reason is, that, as this water is the cause of life and growth to the creation, animal and vegetable, so, the Spirit is the alone source of spiritual life and growth. The primeval type of that blessed Agent was the river that watered the Garden of Eden, and thence flowing, was parted into four streams to water the earth. This river was a fitting symbol of the Holy Spirit, “which proceedeth from the Father,” the “pure river of water of life clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb” (John xv, 26; Rev. xxii, 1), not only in its life-giving virtue, but in its abundance and diffusion. But the fall cut man off from its abundant and perennial stream, and thenceforth the figure, as traceable through the Scriptures, ever looks forward to that promised time when the ruin of the fall will be repaired, and the gates of Paradise thrown open again. In the last chapters of the Revelation, that day is revealed in a vision of glory. There is no more sea; but the river of life pours its exhaustless crystal waters through the restored Eden of God. But the garden is no longer the retired home of one human 33pair, but is built up, a great city, with walls of gems and streets of gold and gates of pearl and the light of the glory of God. And the nations of them that are saved do walk in the light of it. But still it is identified as the same of old, by the flowing river and the tree of life in the midst on its banks. (Rev. ii, 7; xxii, 1, 2; and compare Psalms xlvi, 4; xxiii, 2; John iv, 10, 14; vii, 38, 39; Zech. xiv. 8.) In Ezekiel (xlvii, 1-12) there appears a vision of this river as a prophecy of God’s grace in store for the last times for Israel and the world. In it, the attention of the prophet and of the reader is called distinctly to several points, all of which bear directly on our present inquiry:

1. The source of the waters. In the Revelation, it is described as proceeding out of the throne of God and the Lamb. In Ezekiel the same idea is presented under the figure of the temple, God’s dwelling-place. The waters issue out from under the threshold of the house “at the south side of the altar”—the altar where the sprinkled blood and burning sacrifices testified to the Person by whom, and the price at which, the Spirit is sent. (Compare John vii, 39; xvi, 7; Acts ii, 33.)

2. The exhaustless and increasing flow of the waters is shown to the prophet, who, at a thousand cubits from their source, is led through them,—a stream ankle deep. A thousand cubits farther, he passed through, and they had risen to his knees. Again, a thousand cubits, and the waters were to his loins; and at a thousand cubits more it was a river that he could not pass over. “And he said unto me, Son of man, hast thou seen this?”

3. The river was a fountain of life. On its banks were “very many trees,” “all trees for meat,” with fadeless leaf and exhaustless fruit, “the fruit thereof for meat, and the leaf thereof for medicine.” “And there shall be a very great multitude of fish” in the Dead Sea, “because these waters shall come thither.” For “it shall come to pass that every thing that liveth which moveth, whithersoever 34the river shall come shall live. Every thing shall live, whither the river cometh.”

4. By these living waters, the Dead Sea of depraved humanity shall be healed. “Now this sea of Sodom,” says Thompson, “is so intolerably bitter, that, although the Jordan, the Arnon, and many other streams have been pouring into it their vast contributions of sweet water for thousands of years, it continues as nauseous and deadly as ever. Nothing lives in it; neither fish nor reptiles nor even animalculæ can abide its desperate malignity. But these waters from the sanctuary heal it. The whole world affords no other type of human apostasy so appropriate, so significant. Think of it! There it lies in its sulphurous sepulcher, thirteen hundred feet below the ocean, steaming up like a huge caldron of smouldering bitumen and brimstone! Neither rain from heaven nor mountain torrents nor Jordan’s flood, nor all combined can change its character of utter death. Fit symbol of that great dead sea of depravity and corruption which nothing human can heal!”[4] But the pure waters of the river of life will yet pour into this sea of death a tide of grace by which “the waters shall be healed.”—Ezek. xxvii, 8.

In the prophecy of Joel (iii, 18,) there is another allusion to these waters. Again, in Zechariah a modified form of the same vision appears. “It shall be in that day that living waters shall go out from Jerusalem; half of them toward the former” (the Eastern or Dead) “sea, and half of them toward the hinder sea” (the Mediterranean). “In summer and winter shall it be;” not a mere winter torrent, as are most of the streams of Palestine, but an unfailing river. (Zech. xiv, 8.)

Such is the type of the Spirit, as his graces flowed in Eden, and shall be given to the world, in the times of restitution. But, for the present times, the symbols of rain and fountains of springing water are used in the Scriptures 35as the appropriate types of the now limited and unequal measure and distribution of the Spirit. The manner and effects of his agency are set forth under three forms, each having its own significance:

1. Inasmuch as the rains of heaven are the great source of life and refreshment to the earth and vegetation, the coming of the Spirit and his efficiency as a life-giving and sanctifying power sent down from heaven are expressed by water, shed down, poured, or sprinkled, as the rain descends. Says God to Israel: “I will pour water upon him that is thirsty, and floods upon the dry ground; I will pour my Spirit upon thy seed and my blessing upon thine offspring.”—Isa. xliv, 3. The Psalmist says of the graces of the Spirit to be bestowed by Messiah, “He shall come down like rain upon the mown grass” (the stubble, after mowing) “as showers that water the earth.”—Psalm lxxii, 6. Of this we shall see more hereafter.

2. The act of faith by which the believer seeks and receives more and more of the indwelling Spirit is symbolized by thirsting and drinking of living water. “Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters.”—Isa. lv, 1. “If any man thirst, let him come unto me and drink.... This he spake of the Spirit which they that believe on him should receive.”—John vii, 37-39. “Let him that is athirst come. And whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely.”—Rev. xxii, 17. The intimate relation which this figure sustains, responsive to the one preceding, is illustrated by the expression wherein God describes the land of promise: “A land of hills and valleys, and drinketh water of the rain of heaven. A land which the Lord thy God careth for.”—Deut. xi, 11, 12. With this, compare the language of Paul: “The earth which drinketh in the rain that cometh oft upon it, and bringeth forth herbs meet for them by whom it is dressed, receiveth blessing of God; but that which beareth thorns and briars is rejected and is nigh unto cursing; whose end is to be 36burned. But, beloved, we are persuaded better things of you.”—Heb. vi, 7-9. The figure is further illustrated in the sublime description given by Ezekiel of the destruction of Assyria, in which he speaks of “the trees of Eden, the choice and best of Lebanon, all that drink water,” and so grow and flourish. (Ezek. xxxi, 16.)

3. The duty of the penitent to yield himself with diligent obedience to the sanctifying power and grace of the Holy Spirit, to put away sin and follow after holiness, is enjoined under the figure of washing himself with water. “Wash ye; make you clean; put away the evil of your doings from before mine eyes; cease to do evil; learn to to well.”—Isa. i, 16, 17. “O Jerusalem, wash thine heart from wickedness, that thou mayest be saved.”—Jer. iv, 14. So, James cries, “Cleanse your hands, ye sinners; and purify your hearts, ye double-minded.”—Jas. iv, 8. In the rite of self-washing, to which these last passages refer, the pure water still symbolized the Holy Spirit given by Jesus Christ; whilst the washing expressed the privilege and duty of God’s people conforming their lives to the law of holiness, and exercising the graces which the Spirit gives.

The interest attaching to the Sinai baptism is greatly enhanced by its immediate and intimate relation to us. The covenant then sealed is the fundamental and perpetual charter of the visible church. The transaction by which it was established was the inauguration of that church. It was the espousal of the bride of Christ, whose betrothal took place in the covenant with Abraham. So it is expressly and repeatedly stated by the Spirit of God in the prophets. (See Jer. ii, 1, 2; Ezek. xvi, 3-14; xxiii; Hos. ii, 2, 15, 16.) It is true that this is controverted. It is asserted that the relations established by the covenants between God and Israel were secular and political, not spiritual; that the blessings therein secured were temporal; that they conveyed nothing but a guarantee that Israel should become a numerous and powerful nation, that God would be their political king, the Head of their commonwealth, and that the land of Palestine should be their possession and home. How utterly at variance with the teachings of God’s Word are these assertions a brief analysis of the record will prove.

The covenant of Sinai was the culmination of a series of transactions which began with the calling of Abram from Ur of the Chaldees. “The Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will show thee; and I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a 38blessing; and I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee; and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed.”—Gen. xii, 1-3. Respecting this record, the following points are made clear in the New Testament: (1) That under the type of Canaan, “the land that I will show thee,” heaven was the ultimate inheritance offered to Abram; and that it was so understood by him and the patriarchs. (Gal. iv, 26; Heb. xi, 10, 14-16.) (2) That the blessings promised through him to all the families of the earth were the atonement and salvation of Jesus Christ; and that this also was so understood by Abram. (Gen. xvii, 7; Gal. iii, 16, John viii, 56.) Thus, in his call from Chaldea, and the promises annexed to it, God “preached before the gospel unto Abraham.”—Gal. iii, 8. So far, certainly, the transaction is eminently spiritual.

About ten years after the coming of Abram into the land of Canaan, the promises were confirmed to him by being incorporated into covenant form, and ratified by a seal. Respecting this first covenant, the record of which is contained in the fifteenth chapter of Genesis, the following are the essential points:

1. The interview was opened by the Lord with an assurance so spiritual and large as to be exhaustive of every thing that heaven can bestow. “The Lord came unto Abram in a vision, saying, Fear not, Abram; I am thy shield, and thy exceeding great reward.” Whatever else was promised or given, after an assurance thus rich and comprehensive of time and eternity, must evidently be interpreted in a sense subordinate to it. No minor particulars can ever exhaust or limit the treasury thus opened. Henceforth God himself belongs to the patriarch.

2. An innumerable seed was assured to him, as heirs with him of the promises; and he is told that not to him but to his seed should the earthly Canaan be given. (Vs. 5, 18; and compare xvii, 7, 8.)

393. Abram’s faith was the condition of the covenant. “He believed in the Lord, and he counted it to him for righteousness.”—Vs. 6.

4. The promises thus made and accepted were confirmed by a sacrifice appointed of God, and his acceptance of it was manifested by the sign of a smoking furnace and a burning lamp, passing between the pieces. (Vs. 8, 9, 17, 18.)

5. It was an express provision of the covenant thus ratified that, so far as it concerned the seed of Abram, its realization was to be held in abeyance four hundred years. (Vs. 13-16.) It was the betrothal, of which the marriage consummation could only take place when the long-suffering of God toward the nations was exhausted and the iniquity of the Amorites was full.

About fifteen years afterward God was pleased to appear again to the patriarch, to renew the covenant, and to confirm it with a new seal. (Gen. xvii, 1-21.) Of this edition of the covenant the principal provisions were: (1) That he should be a father of many nations. (2) That Canaan should be, to him and his seed, an everlasting possession. (3) That God would be a God to him and to his seed after him. By the first of these promises, as Paul assures us, Abraham was made the heir of the world, and the father of all believers; of the gospel day, as well as before it; of the Gentile nations, as well as of Israel. (Rom. iv, 11-18; Gal. iii, 7-9, 14.) Hence the name given him of God, in confirmation of this promise (Gen. xvii, 5), Abraham, “Father of a multitude,” Father of the church of Christ. But the central fact of this transaction remains. The covenant was epitomized in one brief word: “I will establish my covenant between me and thee and thy seed after thee, in their generations, for an everlasting covenant, to be a God unto thee and to thy seed after thee.”—v. 7.

401. The covenant thus set forth is “an everlasting covenant;” no lapse of time can alter or abrogate its terms.

2. By it the Godhead assumed toward Abraham and his seed relations peculiar, exclusive, and of boundless grace. God, even the infinite and almighty God, can do no more than to give himself. Christian can conceive no more, and the most blessed of all heaven’s ransomed host will know and enjoy no more than this, which was first assured to Abram, in those words, “Fear not; I am thy shield, and thy exceeding great reward;” and is now concentrated into that one word, “Thy God.” What can there be, not spiritual, in a covenant thus summed? And what spiritual gift or blessing is not comprehended in it? But this is not all. Whilst Paul testifies that all who believe are the seed of Abraham, and heirs with him of the promises, he also declares that Christ was the seed to whom distinctively and on behalf of his people they were addressed: “To Abraham and his seed were the promises made. He saith not, And to seeds as of many, but as of one: And to thy seed, which is Christ.”—Gal. iii, 16. It thus appears that the promises in question were addressed immediately to the Lord Jesus, and they indicate all the intimacy and grace of his relation to the Father,—the relation which he claimed, when, from the cross, he appealed to the Father by that title: “My God! my God! why hast thou forsaken me?” It follows, that the title of others to this promise is mediate only: “As many of you as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ.... And if ye be Christ’s, then are ye Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.”—Ib. 27-29.

It was with a view to this relation of the covenant to the Lord Jesus, that circumcision was appointed as a seal of it. In that rite was signified satisfaction to justice through the blood of the promised Seed, and the crucifying of our old man with him, to the putting off and destroying 41of the body of the flesh. (Deut. x, 16; Jer. iv, 4; Rom. vi, 6; Col. ii, 11, 12.)

Upon occasion of the offering of Isaac, the covenant was again confirmed to Abraham in promises which do not mention Canaan, but are summed in the intensive assurances: “In blessing I will bless thee, and in multiplying I will multiply thy seed as the stars of heaven, and as the sand which is upon the sea-shore, and thy seed shall possess the gate of his enemies, and in thy seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed.”—Gen. xxii, 16-18. What seed it was to whom these promises were made, we have seen before. The assurance to him of triumph over his enemies renews the pledge made to Eve, through the curse upon the serpent, “Her seed shall bruise thy head.”—Gen. iii, 15. Of the same thing, the Spirit in Isaiah says: “Therefore will I divide him a portion with the great, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong; because he hath poured out his soul unto death, and he was numbered with the transgressors; and he bare the sin of many and made intercession for the transgressors.”—Isa. liii, 12. Of it, Paul says: “He must reign, till he hath put all enemies under his feet.”—1 Cor. xv, 25.

The covenant thus interpreted, was confirmed to Abraham with an oath (v. 16), of which Paul says: “Wherein God, willing more abundantly to show unto the heirs of promise the immutability of his counsel, confirmed it by an oath; that, by two immutable things, in which it was impossible for God to lie, we might have a strong consolation who have fled for refuge to lay hold upon the hope set before us. Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul both sure and steadfast, and which entereth into that within the veil, whither the forerunner is for us entered, even Jesus.”—Heb. vi, 17-20. Here, again, it appears that the covenant with Abraham comprehended in its terms the very highest hopes which Christ’s blood has purchased,—which he, in heaven, as his people’s forerunner, 42now possesses, and which with him they shall finally share; and that the oath by which it was confirmed contemplated these very things, and was designed to perfect the faith and confidence of his people, in the gospel day, as well as of the patriarchs and saints of old.

It is thus manifest that while the Abrahamic covenant did undoubtedly convey to Abraham and his seed after the flesh many and precious temporal blessings, it was at the same time an embodiment of the very terms of the covenant between God and his Christ; that its provisions of grace to man are bestowed wholly in Christ; and that it is, therefore, exclusive and everlasting. There can be no reconciliation between God and man, but upon the terms of this covenant. There can, therefore, be no people of God, no true church of Christ, but of those who accept and are embraced in, and built upon, that alone foundation, “the everlasting covenant” made with Abraham.