TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

Anarchy and Anarchists.

A HISTORY OF

THE RED TERROR AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION

IN AMERICA AND EUROPE.

COMMUNISM, SOCIALISM, AND NIHILISM

IN DOCTRINE AND IN DEED.

THE CHICAGO HAYMARKET CONSPIRACY,

AND THE DETECTION AND TRIAL OF THE CONSPIRATORS.

BY

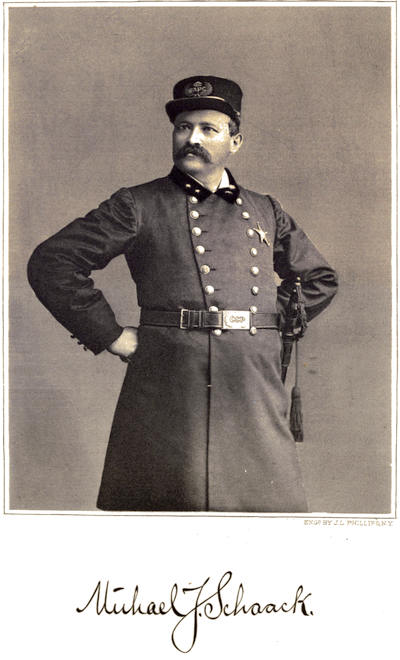

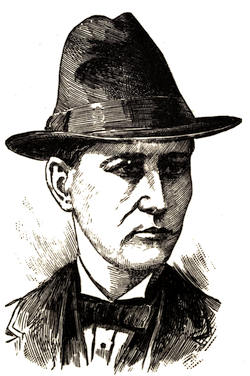

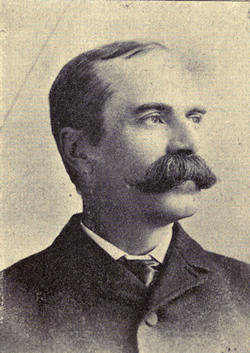

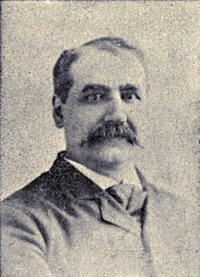

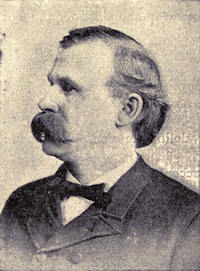

Michael J. Schaack,

Captain of Police.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM AUTHENTIC PHOTOGRAPHS, AND FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS

By Wm. A. McCullough, Wm. Ottman, Louis Braunhold, True Williams, Chas. Foerster, O. F. Kritzner, and Others.

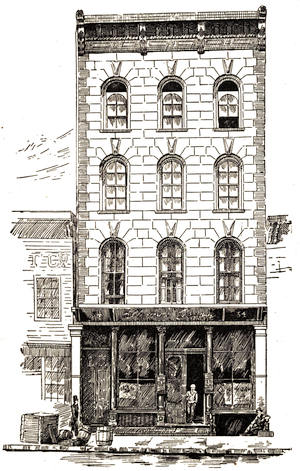

CHICAGO:

F. J. Schulte & Company.

New York and Philadelphia: W. A. Houghton.

St. Louis: S. F. Junkin & Co.—— Pittsburg: P. J. Fleming & Co.

MDCCCLXXXIX.

Copyright, 1889,

BY MICHAEL J. SCHAACK.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

⁂THE ILLUSTRATIONS IN THIS WORK ARE ALL ORIGINAL, AND ARE

PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT.

TO

HON. JOSEPH E. GARY

AND TO

HON. JULIUS S. GRINNELL

THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY

THE AUTHOR.

PREFACE.

*

*——*

IT has seemed to me that there should be a history of the development, the revolt, and the tragedy of Anarchy in Chicago. This history I have written as impartially and as fairly as I knew how to write it. I have kept steadily before my eyes the motto,—

“Nothing extenuate, nor set down aught in malice.”

It will be found in the succeeding pages that neither animosity against the revolutionists, nor partiality to the State, has influenced the work. I have dealt with this episode in Chicago’s history as calmly and as fairly as I am able. I have tried to put myself in the position of the misguided men whose conspiracy led to the Haymarket explosion and to the gallows; to understand their motives; to appreciate their ideals—for so only could this volume be properly written.

And to present a broader view, I have added a history of all forms of Socialism, Communism, Nihilism and Anarchy. In this, though necessarily brief, it has been the purpose to give all the important facts, and to set forth the theories of all those who, whether moderate or radical, whether sincerely laboring in the interests of humanity or boisterously striving for notoriety, have endeavored or pretended to improve upon the existing order of society.

After the dynamite bomb exploded, carrying death into the ranks of men with whom I had been for years closely associated—after an impudent attack had been made upon our law and upon our system, which I was sworn to defend—it came to me as a duty to the State, a duty to my dead and wounded comrades, to bring the guilty men to justice; to expose the conspiracy to the world, and thus to assist in vindicating the law. How the duty was performed, this story tells.

It is a plain narrative whose interest lies in the momentous character of the facts which it relates. Much of it is now for the first time given to the public. I have drawn upon the records of the case, made in court, but more especially upon the reports made to me, during the progress of the investigation, by the many detectives who were working under my direction.

I can say for my book no more than this: that from the first page to the last there is no material statement which is not to my knowledge true. The reader, then, may at least depend upon the accuracy of the information presented here, even if I cannot make any other claim.

It would be unfair and ungrateful if I did not seize this opportunity to[vi] put on lasting record my obligations to Judge Julius S. Grinnell, who was State’s Attorney during the investigation. His support, steady and full of tact, enabled me to go through with the work, in spite of obstacles deliberately put in my way. My position was a delicate and difficult one: had it not been for him, and for others, success would have been almost impossible.

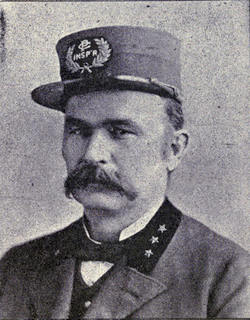

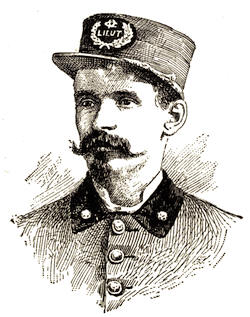

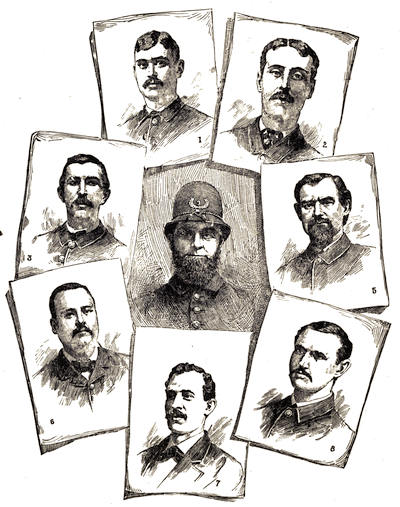

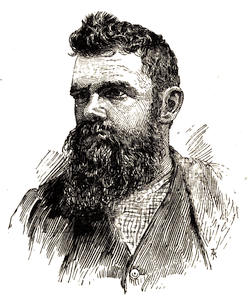

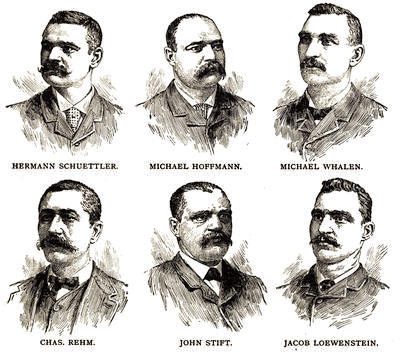

Nor can I forego this occasion to bear testimony to the magnificent police work done in the case by Inspector Bonfield and his brother, James Bonfield, and by the officers who acted directly with me. These were Lieut. Charles A. Larsen and Officers Herman Schuettler, Michael Whalen, Jacob Loewenstein, Michael Hoffman, Charles Rehm, John Stift and B. P. Baer. Mr. Edmund Furthmann, at that time Assistant State’s Attorney, as I have elsewhere recorded, worked upon the inquiry into the conspiracy with an acumen, a perseverance and an industry which were beyond all praise. I knew, when he was first associated with me in the case, that the outcome must be a victory for outraged law, and the result vindicated the prediction. To Mr. Thomas O. Thompson and to Mr. John T. McEnnis much of the literary form of this volume is to be credited, and to them also I am under lasting obligations.

Michael J. Schaack.

Chicago, February, 1889.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

*

*——*

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Beginning of Anarchy—The German School of Discontent—The Socialist Future—The Asylum in London—Birth of a Word—Work of the French Revolution—The Conspiracy of Babeuf—Etienne Cabet’s Experiment—The Colony in the United States—Settled at Nauvoo—Fourier and his System—The Familistère at Guise—Louis Blanc and the National Work-shops—Proudhon, the Founder of French Anarchy—German Socialism: Its Rise and Development—Rodbertus and his Followers—“Capital,” by Karl Marx—The “Bible of the Socialists”—The Red Internationale—Bakounine and his Expulsion from the Society—The New Conspiracy—Ferdinand Lassalle and the Social Democrats—The Birth of a Great Movement—Growth of Discontent—Leaders after Lassalle—The Central Idea of the Revolt—American Methods and the Police Position, | 17 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Dynamite in Politics-Historical Assassinations—Infernal Machines in France—The Inventor of Dynamite—M. Noble and his Ideas—The Nitro-Compounds—How Dynamite is Made—The New French Explosive—“Black Jelley” and the Nihilists—What the Nihilists Believe and What they Want—The Conditions in Russia—The White and the Red Terrors—Vera Sassoulitch—Tourgenieff and the Russian Girl—The Assassination of the Czar—“It is too Soon to Thank God”—The Dying Emperor—Two Bombs Thrown—Running Down the Conspirators—Sophia Perowskaja, the Nihilist Leader—The Handkerchief Signal—The Murder Roll—Tried and Convicted—A Brutal Execution—Five Nihilists Pay the Penalty—Last Words Spoken but Unheard—A Deafening Tattoo—The Book-bomb and the Present Czar—Strychnine-coated Bullets—St. Peter and Paul’s Fortress—Dynamite Outrages in England—The Record of Crime—Twenty-nine Convicts and their Offenses—Ingenious Bomb-making—The Failures of Dynamite, | 28 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

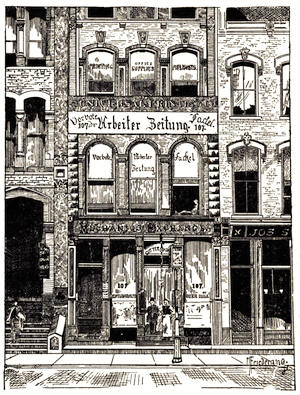

| The Exodus to Chicago—Waiting for an Opportunity—A Political Party Formed—A Question of $600,000—The First Socialist Platform—Details of the Organization—Work at the Ballot-Box—Statistics of Socialist Progress—The “International Workingmen’s Party” and The “Workingmen’s Party of the United States”—The Eleven Commandments of Labor—How the Work was to be Done—A Curious Constitution—Beginnings of the Labor Press—The Union Congress—Criticising the Ballot-Box—The Executive Committee and its Powers—Annals of 1876—A Period of Preparation—The Great Railroad Strikes of 1877—The First Attack on Society—A Decisive Defeat—Trying Politics Again—The “Socialistic Party”—Its Leaders and its Aims—August Spies as an Editor—Buying the Arbeiter-Zeitung—How the Money was Raised—Anarchist Campaign Songs—The Group Organization—Plan of the Propaganda—Dynamite First Taught—“The Bureau of Information”—An Attack on Arbitration—No Compromise with Capital—Unity of the Internationalists and the Socialists, | 44 |

| CHAPTER IV. [viii] | |

| Socialism, Theoretic and Practical—Statements of the Leaders—Vengeance on the “Spitzels”—The Black Flag in the Streets—Resolutions in the Alarm—The Board of Trade Procession—Why it Failed—Experts on Anarchy—Parsons, Spies, Schwab and Fielden Outline their Belief—The International Platform—Why Communism Must Fail—A French Experiment and its Lesson—The Law of Averages—Extracts from the Anarchistic Press—Preaching Murder—Dynamite or the Ballot-Box?—“The Reaction in America”—Plans for Street Fighting—Riot Drill and Tactics—Bakounine and the Social Revolution—Twenty-one Statements of an Anarchist’s Duty—Herways’ Formula—Predicting the Haymarket—The Lehr und Wehr Verein and the Supreme Court—The White Terror and the Red—Reinsdorf, the Father of Anarchy—His Association with Hoedel and Nobiling—Attempt to Assassinate the German Emperor—Reinsdorf at Berlin—His Desperate Plan—“Old Lehmann” and the Socialist’s Dagger—The Germania Monument—An Attempt to Kill the Whole Court—A Culvert Full of Dynamite—A Wet Fuse and no Explosion—Reinsdorf Condemned to Death—His Last Letters—Chicago Students of his Teachings—De Tocqueville and Socialism, | 74 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

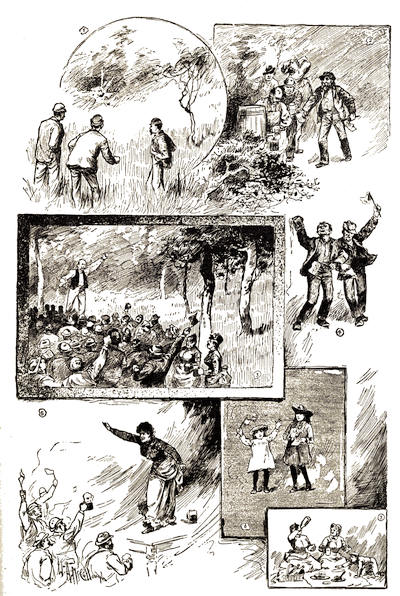

| The Socialistic Programme—Fighting a Compromise—Opposition to the Eight-hour Movement—The Memorial to Congress—Eight Hours’ Work Enough—The Anarchist Position—An Alarm Editorial—“Capitalists and Wage Slaves”—Parsons’ Ideas—The Anarchists and the Knights of Labor—Powderly’s Warning—Working up a Riot—The Effect of Labor-saving Machinery—Views of Edison and Wells—The Socialistic Demonstration—The Procession of April 25, 1886—How the Arbeiter-Zeitung Helped on the Crisis—The Secret Circular of 1886, | 104 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

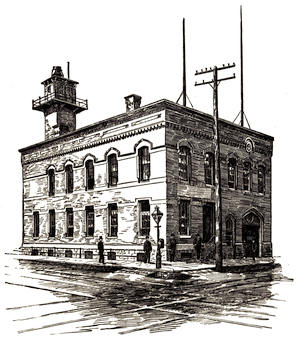

| The Eight-hour Movement—Anarchist Activity—The Lock-out at McCormick’s—Distorting the Facts—A Socialist Lie—The True Facts about McCormick’s—Who Shall Run the Shops?—Abusing the “Scabs”—High Wages for Cheap Work—The Union Loses $3,000 a Day—Preparing for Trouble—Arming the Anarchists—Ammunition Depots—Pistols and Dynamite—Threatening the Police—The Conspirators Show the White Feather—Capt. O’Donnell’s Magnificent Police Work—The Revolution Blocked—A Foreign Reservation—An Attempt to Mob the Police—The History of the First Secret Meeting—Lingg’s First Appearance in the Conspiracy—The Captured Documents—Bloodshed at McCormick’s—“The Battle Was Lost”—Officer Casey’s Narrow Escape, | 112 |

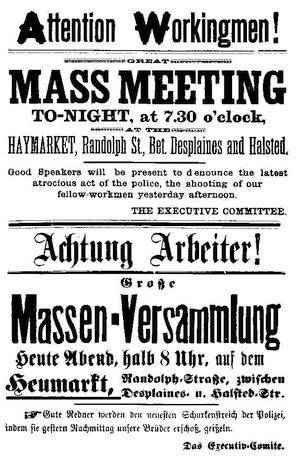

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Coup d’État a Miscarriage—Effect of the Anarchist Failure at McCormick’s—“Revenge”—Text of the Famous Circular—The German Version—An Incitement to Murder—Bringing on a Conflict—Engel’s Diabolical Plan—The Rôle of the Lehr und Wehr Verein—The Gathering of the Armed Groups—Fischer’s Sanguinary Talk—The Signal for Murder—“Ruhe” and its Meaning—Keeping Clear of the Mouse-Trap—The Haymarket Selected—Its Advantages for Revolutionary War—The Call for the Murder Meeting—“Workingmen, Arm Yourselves”—Preparing [ix]the Dynamite—The Arbeiter-Zeitung Arsenal—The Assassins’ Roost at 58 Clybourn Avenue—The Projected Attack on the Police Stations—Bombs for All who Wished Them—Waiting for the Word of Command—Why it was not Given—The Leaders’ Courage Fails, | 129 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

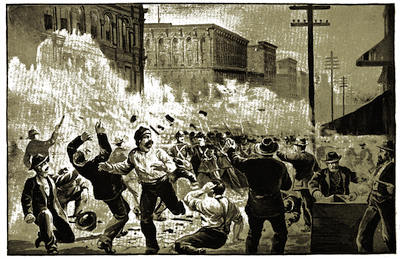

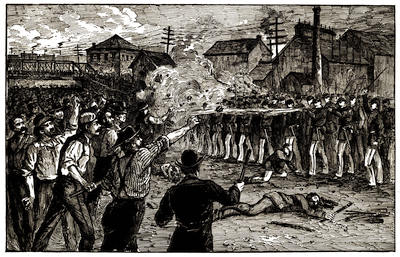

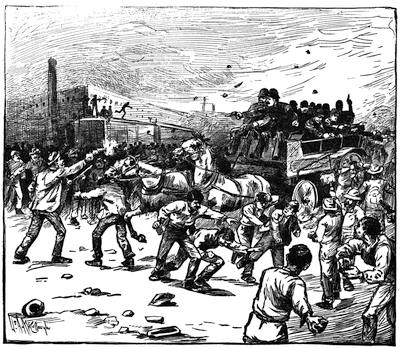

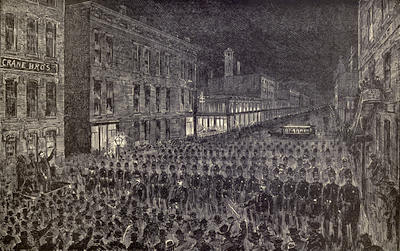

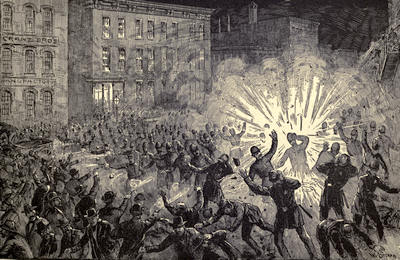

| The Air Full of Rumors—A Riot Feared—Police Preparations—Bonfield in Command—The Haymarket—Strategic Value of the Anarchists’ Position—Crane’s Alley—The Theory of Street Warfare—Inflaming the Mob—Schnaubelt and his Bomb—“Throttle the Law”—The Limit of Patience Reached—“In the Name of the People, Disperse”—The Signal Given—The Crash of Dynamite First Heard on an American Street—Murder in the Air—A Rally and a Charge—The Anarchists Swept Away—A Battle Worthy of Veterans, | 139 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Dead and the Wounded—Moans of Anguish in the Police Station—Caring for Friend and Foe—Counting the Cost—A City’s Sympathy—The Death List—Sketches of the Men—The Doctors’ Work—Dynamite Havoc—Veterans of the Haymarket—A Roll of Honor—The Anarchist Loss—Guesses at their Dead—Concealing Wounded Rioters—The Explosion a Failure—Disappointment of the Terrorists, | 149 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

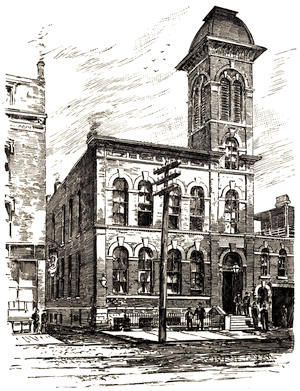

| The Core of the Conspiracy—Search of the Arbeiter-Zeitung Office—The Captured Manuscript—Jealousies in the Police Department—The Case Threatened with Failure—Stupidity at the Central Office—Fischer Brought in—Rotten Detective Work—The Arrest of Spies—His Egregious Vanity—An Anarchist “Ladies’ Man”—Wine Suppers with the Actresses—Nina Van Zandt’s Antecedents—Her Romantic Connection with the Case—Fashionable Toilets—Did Spies Really Love Her?—His Curious Conduct—The Proxy Marriage—The End of the Romance—The Other Conspirators—Mrs. Parsons’ Origin—The Bomb-Thrower in Custody—The Assassin Kicked Out of the Chief’s Office—Schnaubelt and the Detectives—Suspicious Conduct at Headquarters—Schnaubelt Ordered to Keep Away From the City Hall—An Amazing Incident—A Friendly Tip to a Murderer—My Impressions of the Schnaubelt Episode—Balthasar Rau and Mr. Furthmann—Phantom Shackles in a Pullman—Experiments with Dynamite—An Explosive Dangerous to Friend and Foe—Testing the Bombs—Fielden and the Chief, | 156 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| My Connection with the Anarchist Cases—A Scene at the Central Office—Mr. Hanssen’s Discovery—Politics and Detective Work—Jealousy Against Inspector Bonfield—Dynamiters on Exhibition—Courtesies to the Prize-fighters—A Friendly Tip—My First Light on the Case—A Promise of Confidence—One Night’s Work—The Chief Agrees to my Taking up the Case—Laying Our Plans—“We Have Found the Bomb Factory!”—Is it a Trap?—A Patrol-wagon Full of Dynamite—No Help Hoped for from Headquarters—Conference with State’s Attorney Grinnell—Furthmann’s Work—Opening up the Plot—Trouble with the Newspaper Men—Unexpected Advantage of Hostile Criticism—Information from Unexpected Quarters—Queer Episodes of the Hunt—Clues Good, Bad and Indifferent—A Mysterious Lady [x]with a Veil—A Conference in my Back Yard—The Anarchists Alarmed—A Breezy Conference with Ebersold—Threatening Letters—Menaces Sent to the Wives of the Men Working on the Case—How the Ladies Behaved—The Judge and Mrs. Gary—Detectives on Each Other’s Trail—The Humors of the Case—Amusing Incidents, | 183 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

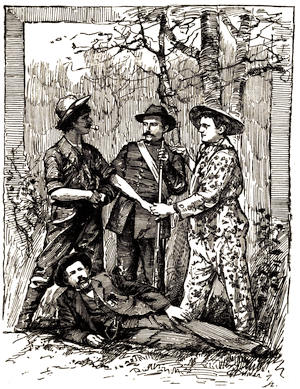

| Tracking the Conspirators—Female Anarchists—A Bevy of Beauties—Petticoated Ugliness—The Breathless Messenger—A Detective’s Danger—Turning the Tables—“That Man is a Detective!”—A Close Call—Gaining Revolutionists’ Confidence—Vouched for by the Conspirators—Speech-making Extraordinary—The Hiding-place in the Anarchists’ Hall—Betrayed by a Woman—The Assassination of Detective Brown at Cedar Lake—Saloon-keepers and the Revolution—“Anarchists for Revenue Only”—Another Murder Plot—The Peep-hole Found—Hunting for Detectives—Some Amusing Ruses of the Revolutionists—A Collector of “Red” Literature and his Dangerous Bonfire—Ebersold’s Vacation—Threatening the Jury—Measures Taken for their Protection—Grinnell’s Danger—A “Bad Man” in Court—The Find at the Arbeiter-Zeitung Office—Schnaubelt’s Impudent Letter—Captured Correspondence—The Anarchists’ Complete Letter-writer, | 206 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

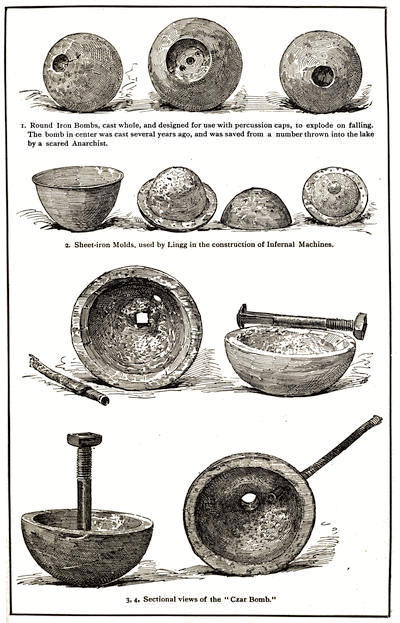

| The Difficulties of Detection—Moving on the Enemy—A Hebrew Anarchist—Oppenheimer’s Story—Dancing over Dynamite—Twenty-Five Dollars’ Worth of Practical Socialism—A Woman’s Work—How Mrs. Seliger Saved the North Side—A Well-merited Tribute—Seliger Saved by his Wife—The Shadow of the Hangman’s Rope—A Hunt for a Witness—Shadowing a Hack—The Commune Celebration—Fixing Lingg’s Guilt—Preparing the Infernal Machines—A Boy Conspirator—Lingg’s Youthful Friend—Anarchy in the Blood—How John Thielen was Taken into Camp—His Curious Confession—Other Arrests, | 230 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

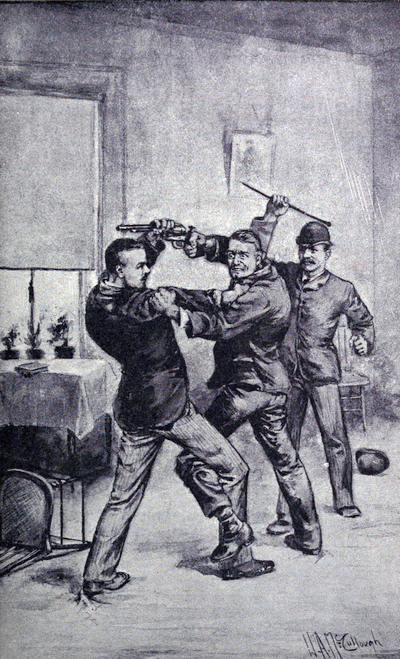

| Completing the Case—Looking for Lingg—The Bomb-maker’s Birth—Was he of Royal Blood?—A Romantic Family History—Lingg and his Mother—Captured Correspondence—A Desperate and Dangerous Character—Lingg Disappears—A Faint Trail Found—Looking for Express Wagon 1999—The Number that Cost the Fugitive his Life—A Desperado at Bay—Schuettler’s Death Grapple—Lingg in the Shackles—His Statement at the Station—The Transfer to the Jail—Lingg’s Love for Children—The Identity of his Sweetheart—An Interview with Hubner—His Confession—The Meeting at Neff’s Place, | 256 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Engel in the Toils—His Character and Rough Eloquence—Facing his Accusers—Waller’s Confession—The Work of the Lehr und Wehr Verein—A Dangerous Organization—The Romance of Conspiracy—Organization of the Armed Sections—Plans and Purposes—Rifles Bought in St. Louis—The Picnics at Sheffield—A Dynamite Drill—The Attack on McCormick’s—A Frightened Anarchist—Lehman in the Calaboose—Information from many Quarters—The Cost of Revolvers—Lorenz Hermann’s Story—Some Expert Lying, | 283 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Pushing the Anarchists—A Scene on a Street-car—How Hermann [xi]Muntzenberg Gave Himself Away—The Secret Signal—“D——n the Informers”—A Satchelful of Bombs—More about Engel’s Murderous Plan—Drilling the Lehr und Wehr Verein—Breitenfeld’s Cowardice—An Anarchist Judas—The Hagemans—Dynamite in Gas-pipe—An Admirer of Lingg—A Scheme to Remove the Author—The Hospitalities of the Police Station—Mrs. Jebolinski’s Indignation—A Bogus Milkman—An Unwilling Visitor—Mistaken for a Detective—An Eccentric Prisoner—Division of Labor at the Dynamite Factory—Clermont’s Dilemma—The Arrangements for the Haymarket, | 312 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Fluttering the Anarchist Dove-cote—Confessions by Piecemeal—Statements from the Small Fry—One of Schnaubelt’s Friends—“Some One Wants to Hang Me”—Neebe’s Bloodthirsty Threats—Burrowing in the Dark—The Starved-out Cut-throat—Torturing a Woman—Hopes of Habeas Corpus—“Little” Krueger’s Work—Planning a Rescue—The Signal “? ? ?” and its Meaning—A Red-haired Man’s Story—Firing the Socialist Heart—Meetings with Locked Doors—An Ambush for the Police—The Red Flag Episode—Beer and Philosophy—Baum’s Wife and Baby—A Wife-beating Revolutionist—Brother Eppinger’s Duties, | 334 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

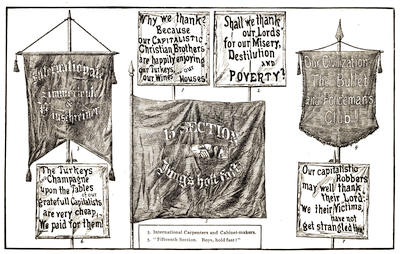

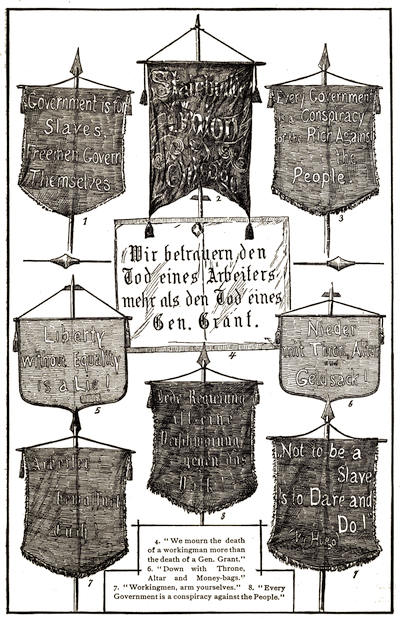

| The Plot against the Police—Anarchist Banners and Emblems—Stealing a Captured Flag—A Mystery at a Station-house—Finding the Fire Cans—Their Construction and Use—Imitating the Parisian Petroleuses—Glass Bombs—Putting the Women Forward—Cans and Bombs Still Hidden Among the Bohemians—Testing the Infernal Machines—The Effects of Anarchy—The Moral to be Drawn—Looking for Labor Sympathy—A Crazy Scheme—Gatling Gun vs. Dynamite—The Threatened Attack on the Station-houses—Watching the Third Window—Selecting a Weapon—Planning Murder—The Test of Would-be Assassins—The Meeting at Lincoln Park—Peril of the Hinman Street Station-house—A Fortunate Escape, | 364 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

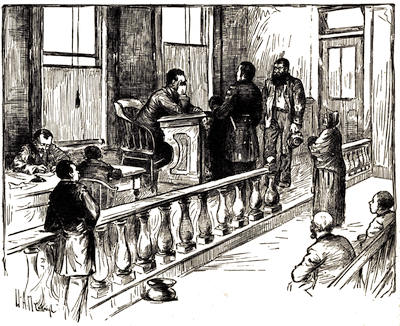

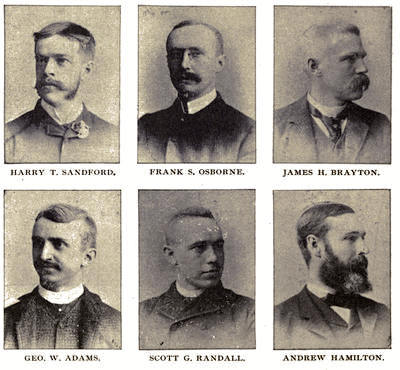

| The Legal Battle—The Beginning of Proceedings in Court—Work in the Grand Jury Room—The Circulation of Anarchistic Literature—A Witness who was not Positive—Side Lights on the Testimony—The Indictments Returned—Selecting a Jury—Sketches of the Jurymen—Ready for the Struggle, | 376 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

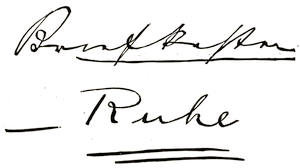

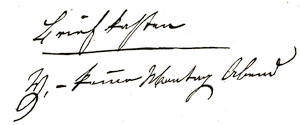

| Judge Grinnell’s Opening—Statement of the Case—The Light of the 4th of May—The Dynamite Argument—Spies’ Fatal Prophecy—The Eight-hour Strike—The Growth of the Conspiracy—Spies’ Cowardice at McCormick’s—The “Revenge” Circular—Work of the Arbeiter-Zeitung and the Alarm—The Secret Signal—A Frightful Plan—“Ruhe”—Lingg, the Bomb-maker—The Haymarket Conspiracy—The Meeting—“We are Peaceable”—After the Murder—The Complete Case Presented, | 390 |

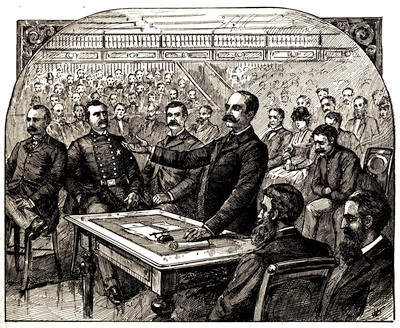

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The Great Trial Opens—Bonfield’s History of the Massacre—How the Bomb Exploded—Dynamite in the Air—A Thrilling Story—Gottfried Waller’s Testimony—An Anarchist’s “Squeal”—The Murder Conspiracy Made Manifest by Many Witnesses, | 404 |

| CHAPTER XXII. [xii] | |

| “We are Peaceable”—Capt. Ward’s Memories of the Massacre—A Nest of Anarchists—Scenes in the Court—Seliger’s Revelations—Lingg, the Bomb-maker—How he cast his Shells—A Dynamite Romance—Inside History of the Conspiracy—The Shadow of the Gallows—Mrs. Seliger and the Anarchists—Tightening the Coils—An Explosive Arsenal—The Schnaubelt Blunder—Harry Wilkinson and Spies—A Threat in Toothpicks—The Bomb Factory—The Board of Trade Demonstration, | 419 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| A Pinkerton Operative’s Adventures—How the Leading Anarchists Vouched for a Detective—An Interesting Scene—An Enemy in the Camp—Getting into the Armed Group—No. 16’s Experience—Paul Hull and the Dynamite Bomb—A Safe Corner Where the Bullets were Thick—A Revolver Tattoo—“Shoot the Devils”—A Reformed Internationalist, | 445 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Reporting under Difficulties—Shorthand in an Overcoat Pocket—An Incriminating Conversation—Spies and Schwab in Danger—Gilmer’s Story—The Man in the Alley—Schnaubelt the Bomb-thrower—Fixing the Guilt—Spies Lit the Fuse—A Searching Cross-Examination—The Anarchists Alarmed—Engel and the Shell Machine—The Find at Lingg’s House—The Author on the Witness-stand—Talks with the Prisoners—Dynamite Experiments—The False Bottom of Lingg’s Trunk—The Material in the Shells—Expert Testimony—Incendiary Banners—The Prosecution Rests—A Fruitless Attempt to have Neebe Discharged, | 457 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| The Programme of the Defense—Mayor Harrison’s Memories—Simonson’s Story—A Graphic Account—A Bird’s-eye View of Dynamite—Ferguson and the Bomb—“As Big as a Base Ball”—The Defense Theory of the Riot—Claiming the Police were the Aggressors—Dr. Taylor and the Bullet-marks—The Attack on Gilmer’s Veracity—Varying Testimony—The Witnesses who Appeared, | 478 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Malkoff’s Testimony—A Nihilist’s Correspondence—More about the Wagon—Spies’ Brother—A Witness who Contradicts Himself—Printing the Revenge Circular—Lizzie Holmes’ Inflammatory Essay—“Have You a Match About You?”—The Prisoner Fielden Takes the Stand—An Anarchist’s Autobiography—The Red Flag the Symbol of Freedom—The “Peaceable” Meeting—Fielden’s Opinion of the Alarm—“Throttling the Law”—Expecting Arrest—More about Gilmer, | 491 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| The Close of the Defense—Working on the Jury—The Man who Threw the Bomb—Conflicting Testimony—Michael Schwab on the Stand—An Agitator’s Adventures—Spies in his Own Defense—The Fight at McCormick’s—The Desplaines Street Wagon—Bombs and Beer—The Wilkinson Interview—The Weapon of the Future—Spies the Reporter’s Friend—Bad Treatment by Ebersold—The Hocking Valley Letter—Albert R. Parsons in his Own Behalf—His Memories of the Haymarket—The Evidence in Rebuttal, | 506 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. [xiii] | |

| Opening of the Argument—Mr. Walker’s Speech—The Law of the Case—Was there a Conspiracy?—The Caliber of the Bullets—Tightening the Chain—A Propaganda on the Witness-stand—The Eight-hour Movement—“One Single Bomb”—The Cry of the Revolutionist—Avoiding the Mouse-trap—Parsons and the Murder—Studying “Revolutionary War”—Lingg and his Bomb Factory—The Alibi Idea, | 525 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

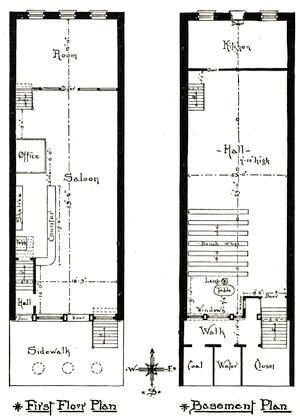

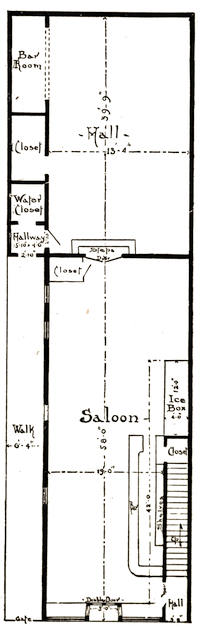

| The Argument for the Defendants—“Newspaper Evidence”—Bringing about the Social Revolution—Arson and Murder—The Right to Property—Evolution or Revolution—Dynamite as an Argument—The Arsenal at 107 Fifth Avenue—Was it all Braggadocio?—An Open Conspiracy—Secrets that were not Secrets—The Case Against the State’s Attorney—A Good Word for Lingg—More About “Ruhe”—The “Alleged” Conspiracy—Ingham’s Answer—The Freiheit Articles—Lord Coleridge on Anarchy—Did Fielden Shoot at the Police?—The Bombs in the Seliger Family—Circumstantial Evidence in Metal—Chemical Analysis of the Czar Bomb—The Crane’s Alley Enigma, | 535 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Foster and Black before the Jury—Making Anarchist History—The Eight Leaders—A Skillful Defense—Alibis All Around—The Whereabouts of the Conspirators—The “Peaceable Dispersion”—A Miscarriage of Revolutionary War—Average Anarchist Credibility—“A Man will Lie to Save his Life”—The Attack on Seliger—The Candy-man and the Bomb-thrower—Conflicting Testimony—A Philippic against Gilmer—The Liars of History—The Search for a Witness—The Man with the Missing Link—The Last Word for the Prisoners—Captain Black’s Theory—High Explosives and Civilization—The West Lake Street Meeting—Defensive Armament—Engel and his Beer—Hiding the Bombs—The Right of Revolution—Bonfield and Harrison—The Socialist of Judea, | 545 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Grinnell’s Closing Argument—One Step from Republicanism to Anarchy—A Fair Trial—The Law in the Case—The Detective Work—Gilmer and his Evidence—“We Knew all the Facts”—Treason and Murder—Arming the Anarchists—The Toy Shop Purchases—The Pinkerton Reports—“A Lot of Snakes”—The Meaning of the Black Flag—Symbols of the Social Revolution—The Daily News Interviews—Spies the “Second Washington”—The Rights of “Scabs”—The Chase Into the River—Inflaming the Workingmen—The “Revenge” Lie—The Meeting at the Arbeiter-Zeitung Office—A Curious Fact about the Speakers at the Haymarket—The Invitation to Spies—Balthasar Rau and the Prisoners—Harrison at the Haymarket—The Significance of Fielden’s Wound—Witnesses’ Inconsistencies—The Omnipresent Parsons—The Meaning of the Manuscript Find—Standing between the Living and the Dead, | 560 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| The Instructions to the Jury—What Murder is—Free Speech and its [xiv]Abuse—The Theory of Conspiracy—Value of Circumstantial Evidence—Meaning of a “Reasonable Doubt”—What a Jury May Decide—Waiting for the Verdict—“Guilty of Murder”—The Death Penalty Adjudged—Neebe’s Good Luck—Motion for a New Trial—Affidavits about the Jury—The Motion Overruled, | 578 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

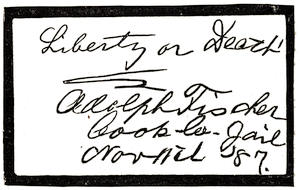

| The Last Scene in Court—Reasons Against the Death Sentence—Spies’ Speech—A Heinous Conspiracy to Commit Murder—Death for the Truth—The Anarchists’ Final Defense—Dying for Labor—The Conflict of the Classes—Not Guilty, but Scapegoats—Michael Schwab’s Appeal—The Curse of Labor-saving Machinery—Neebe Finds Out what Law Is—“I am Sorry I am not to be Hung”—Adolph Fischer’s Last Words—Louis Lingg in his own Behalf—“Convicted, not of Murder, but of Anarchy”—An Attack on the Police—“I Despise your Order, your Laws, your Force-propped Authority. Hang me for it!”—George Engel’s Unconcern—The Development of Anarchy—“I Hate and Combat, not the Individual Capitalist, but the System”—Samuel Fielden and the Haymarket—An Illegal Arrest—The Defense of Albert R. Parsons—The History of his Life—A Long and Thrilling Speech—The Sentence of Death—“Remove the Prisoners,” | 587 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| In the Supreme Court—A Supersedeas Secured—Justice Magruder Delivers the Opinion—A Comprehensive Statement of the Case—How Degan was Murdered—Who Killed Him?—The Law of Accessory—The Meaning of the Statute—Were the Defendants Accessories?—The Questions at Issue—The Characteristics of the Bomb—Fastening the Guilt on Lingg—The Purposes of the Conspiracy—How they were Proved—A Damning Array of Evidence—Examining the Instructions—No Error Found in the Trial Court’s Work—The Objection to the Jury—The Juror Sandford—Judge Gary Sustained—Mr. Justice Mulkey’s Remarks—The Law Vindicated, | 608 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

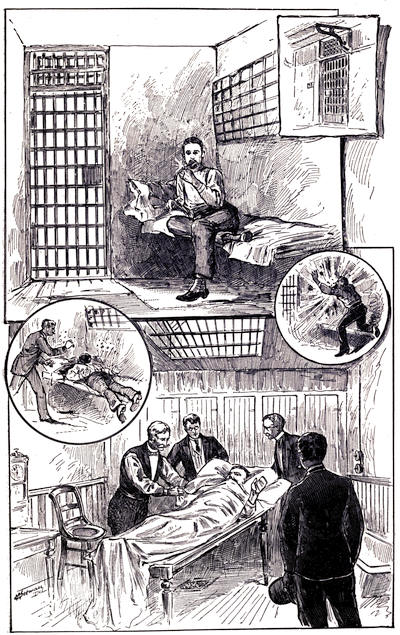

| The Last Legal Struggle—The Need of Money—Expensive Counsel Secured—Work of the “Defense Committee”—Pardon, the Only Hope—Pleas for Mercy to Gov. Oglesby—Curious Changes of Sentiment—Spies’ Remarkable Offer—Lingg’s Horrible Death—Bombs in the Starch-box—An Accidental Discovery—My own Theory—Description of the “Suicide Bombs”—Meaning of the Short Fuse—“Count Four and Throw”—Details of Lingg’s Self-murder—A Human Wreck—The Bloody Record in the Cell—The Governor’s Decision—Fielden and Schwab Taken to the Penitentiary, | 620 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

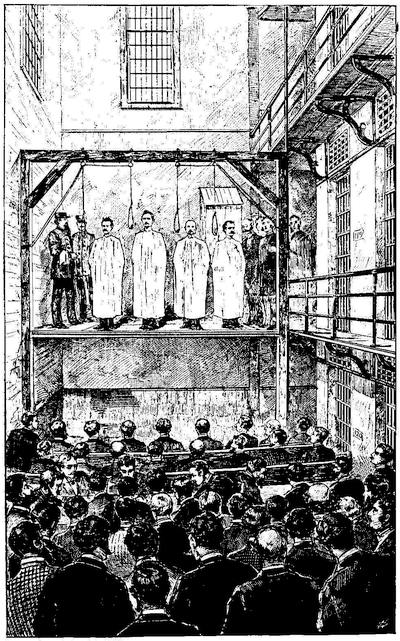

| The Last Hours of the Doomed Men—Planning a Rescue—The Feeling in Chicago—Police Precautions—Looking for a Leak—Vitriol for a Detective—Guarding the Jail—The Dread of Dynamite—How the Anarchists Passed their Last Night—The Final Partings—Parsons Sings “Annie Laurie”—Putting up the Gallows—Scenes Outside the Prison—A Cordon of Officers—Mrs. Parsons Makes a Scene—The Death Warrants—Courage of the Condemned—Shackled and Shrouded for the Grave—The March to the Scaffold—Under the Dangling Ropes—The Last Words—“Hoch die Anarchie!”—“My Silence will be More Terrible than Speech”—“Let the Voice of the People be Heard”—The Chute to Death—Preparations for the Funeral—Scenes [xv]at the Homes of the Dead Anarchists—The Passage to Waldheim—Howell Trogden Carries the American Flag—Captain Black’s Eulogy—The Burial—Speeches by Grottkau and Currlin—Was Engel Sincere?—His Advice to his Daughter—A Curious Episode—Adolph Fischer and his Death-watch, | 639 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

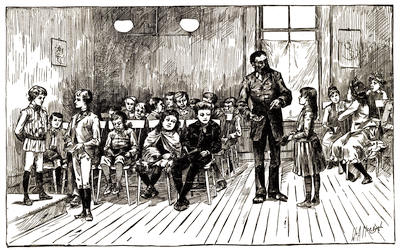

| Anarchy Now—The Fund for the Condemned Men’s Families—$10,000 Subscribed—The Disposition of the Money—The Festival of Sorrow—Parsons’ Posthumous Letter—The Haymarket Monument—Present Strength of the Discontented—7,300 Revolutionists in Chicago—A Nucleus of Desperate Men—The New Organization—Building Societies and Sunday-schools—What the Children are Taught—Education and Blasphemy—The Secret Propaganda—Bodendick and his Adventures—“The Rebel Vagabond”—The Plot to Murder Grinnell, Gary and Bonfield—Arrest of the Conspirators Hronek, Capek, Sevic and Chleboun—Chleboun’s Story—Hronek Sent to the Penitentiary, | 657 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| The Movement in Europe—Present Plans of the Reds—Stringent Measures Adopted by Various European Governments—Bebel and Liebknecht—A London Celebration—Whitechapel Outcasts—“Blood, Blood, Blood!”—Verestchagin’s Views—The Bulwarks of Society—The Condition of Anarchy in New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Cincinnati, St. Louis and other American Cities—A New Era of Revolutionary Activity—A Fight to the Death—Are we Prepared? | 682 |

| Appendices, | 691 |

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION—“THE FEAST OF REASON.”

ANARCHY AND ANARCHISTS.

*

*——*

CHAPTER I.

The Beginning of Anarchy—The German School of Discontent—The Socialist Future—The Asylum in London—Birth of a Word—Work of the French Revolution—The Conspiracy of Babeuf—Etienne Cabet’s Experiment—The Colony in the United States—Settled at Nauvoo—Fourier and his System—The Familistère at Guise—Louis Blanc and the National Work-shops—Proudhon, the Founder of French Anarchy—German Socialism: Its Rise and Development—Rodbertus and his Followers—“Capital,” by Karl Marx—The “Bible of the Socialists”—The Red Internationale—Bakounine and his Expulsion from the Society—The New Conspiracy—Ferdinand Lassalle and the Social Democrats—The Birth of a Great Movement—Growth of Discontent—Leaders after Lassalle—The Central Idea of the Revolt—American Methods and the Police Position.

THE conspiracy which culminated in the blaze of dynamite and the groans of murdered policemen on that fatal night of May 4th, 1886, had its origin far away from Chicago, and under a social system very different from ours.

In order that the reader may understand the tragedy, it will be necessary for me to go back to the commencement of the agitation, and to show how Anarchy in this city is the direct development of the social revolt in Europe. After “the red fool fury of the French” had burnt itself out, the nations of the Old World, exhausted by the Titanic struggle with Napoleon, lay quiet for nearly a quarter of a century. The doctrines which had brought on the Reign of Terror had not died. After a period of quiet, the evangel of the Social Revolution again began. There was uneasiness throughout Europe. In France the Bourbons were driven out, although the cause of the people was betrayed by Louis Napoleon. In Germany the demand for a constitution was pushed so strongly that even the sturdy Hohenzollerns had to give way before it. In Hungary there was a popular ferment. Poland was ready for a new rising against Russia. In Russia the movement which subsequently came to be known as Nihilism was born. In Italy Garibaldi and Mazzini were laying the foundations for the throne which the house of Savoy built upon the work of the secret societies.

Nor must the reader believe that all this turmoil had not beneath it real grievances and honest causes. The peasantry and the laboring classes of Europe had been oppressed and plundered for centuries. The common people were just beginning to learn their power, and, while the excesses into which they were led were deplorable, it is not difficult to understand the causes which made the crisis inevitable.

There is nothing ever lost by endeavoring to enter fairly and impartially into another’s position—by trying to understand the reasons which move men, and the creeds which sway them. Anarchy as a theory is as old as the school men of the middle ages. It was gravely debated in the monasteries, and supported by learned casuists five centuries ago. As a practice it was first taught in France, and later in Germany. It caught the unthinking, impressible throng as the proper protest against too much government and wrong government. It was ably argued by leaders capable of better things,—men who turned great talents toward the destruction of society instead of its upbuilding,—and the fruit of their teachings we have with us in Chicago to-day.

STORMING THE BASTILE.

Our Anarchy is of the German school, which is more nearly akin to Nihilism than to the doctrines taught in France. It is founded upon the teachings of Karl Marx and his disciples, and it aims directly at the complete destruction of all forms of government and religion. It offers no solution of the problems which will arise when society, as we understand it, shall disappear, but contents itself with declaring[19] that the duty at hand is tearing down; that the work of building up must come later. There are several reasons why the revolutionary programme stops short at the work of Anarchy, chief among which is the fact that there are as many panaceas for the future as there are revolutionists, and it would be a hopeless task to think of binding them all to one platform of construction. The Anarchists are all agreed that the present system must go, and so far they can work together; after that each will take his own path into Utopia.

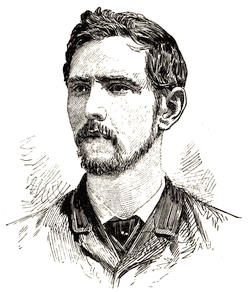

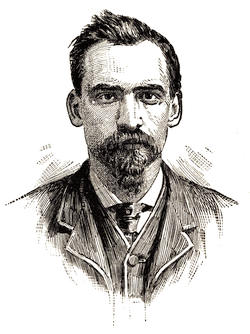

KARL MARX.

Their dream of the future is accordingly as many-colored as Joseph’s coat. Each man has his own ideal. Engels, who is Karl Marx’s successor in the leadership of the movement, believes that men will associate themselves into organizations like coöperative societies for mutual protection, support and improvement, and that these will be the only units in the country of a social nature. There will be no law, no church, no capital, no anything that we regard as necessary to the life of a nation.

The theory of Anarchy will, however, be sufficiently developed in the pages that follow. It is its history as a school which must first be examined.

England is really responsible for much of the present strength of the conspiracy against all governments, for it was in the secure asylum of London that speculative Anarchy was thought out by German exiles for German use, and from London that the “red Internationale” was and probably is directed. This was the result of political scheming, for the fomenting of discontent on the continent has always been one of the weapons in the British armory.

In England itself the movement has only lately won any prominence, although it was in England that it was baptized “Socialism” by Robert Owen, in 1835, a name which was afterwards taken up both in France and Germany. The English development is hardly worth consideration in as brief a presentation of the subject as I shall be able to give. Before passing to an investigation of the growth and the history of Socialism and Anarchy, I wish to express here, once for all, my obligations to Prof. Richard T. Ely’s most excellent history of “French and German Socialism[20] in Modern Times.” This monograph, like everything else which has come from the pen of this gifted young economist, contains so clear a statement and so complete a marshaling of the facts that it is not necessary to go beyond it for the story of continental discontent.

The French Revolution drew a broad red line across the world’s history. It is the most momentous fact in the annals of modern times. There is no need for us to go behind it, or to examine its causes. We can take it as a fact—as the great revolt of the common people—and push on to the things that followed it.

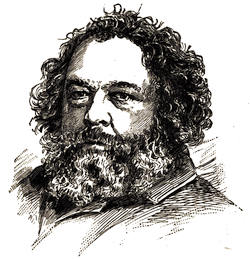

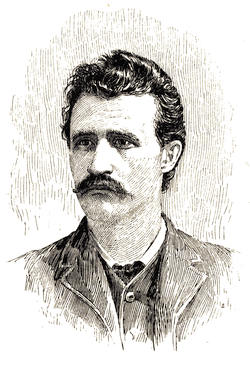

MICHAEL BAKOUNINE.

Babeuf—“Gracchus” Babeuf, as he called himself—after serving part of a term in prison for forgery, escaped, went to Paris in the heat of the Revolution, and started The Tribune of the People, the first Socialistic paper ever published. He was too incendiary even for Robespierre, and was imprisoned in 1795. In prison he formed the famous “Conspiracy of Babeuf,” which was to establish the Communistic republic. For this conspiracy he and Darthé were beheaded May 24, 1797.

Etienne Cabet was a Socialist before the term was invented, but he was a peaceful and honest one. He published, in 1842, his “Travels in Icaria,” describing an ideal state. Like most political reformers, he chose the United States as the best place to try his experiment upon. It is a curious fact that there is not a nation in Europe, however much of a failure it may have made of all those things that go to make up rational liberty, which does not feel itself competent to tell us just what we ought to do, instead of what we are doing. Cabet secured a grant of land on the Red River in Texas just after the Mexican War, and a colony of Icarians came out. They took the yellow fever and were dispersed before Cabet came with the second part of the colony. About this time the Mormons left Nauvoo in Illinois, and the Icarians came to take their places. The colony has since established itself at Grinnell, Iowa, and a branch is at San Bernardino, California. The Nauvoo settlement has, I believe, been abandoned.

Babeuf and Cabet prepared the way for Saint Simon. He was a[21] count, and a lineal descendant of Charlemagne. He fought in our War of the Revolution under Washington, and passed its concluding years in a British prison. He preached nearly the modern Socialism,—the revolt of the proletariat against property,—and his work has indelibly impressed itself upon the whole movement in France.

Charles Fourier, born in 1772, was the son of a grocer in Besançon, and he was a man who exercised great influence upon the movement among the French. He was rather a dreamer than a man of action, and, although attempts have been made to carry his familistère into practice, there is no conspicuous success to record, save, perhaps, that of the familistère at Guise, in France, which has been conducted for a long time on the principles laid down by Fourier.

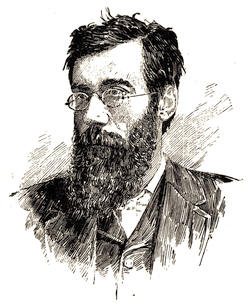

PIERRE JOSEPH PROUDHON.

All these men had before them concrete schemes for a new society in which the evils of the present system would be avoided by what they considered a more equable division of wealth, and each made the effort to carry his scheme from theory into practice, so that the world might see the success and imitate it. Following them came the men who held that, before the new society can be formed, the old society must be got rid of—the men who see but one way towards Socialism, and that through Anarchy.

Louis Blanc was the first of these, although he would not have described himself as an Anarchist, nor would it be fair to call him one. He represented the transition stage. He attempted political reforms of a most sweeping character during the revolution of 1848. The government of the day established “national work-shops” as a concession to him. Of these more is said hereafter.

Pierre Joseph Proudhon, born in Besançon July 15, 1809, is really the father of French Anarchy. His great work, “What Is Property?” was published in 1840, and he declared that property was theft and property-holders thieves. It is to this epoch-making work that the whole school[22] of modern Anarchy, in any of its departments, may be traced. Proudhon was fired by an actual hatred of the rich. He describes a proprietor as “essentially a libidinous animal, without virtue and without shame.” The importance of his work is shown by the effect it has had even upon orthodox political economy, while on the other side it has been the inspiration of Karl Marx. Proudhon died in Passy in 1865.

Since his time until within the last year or two, French Socialism has been but a reflex of the German school. It has produced no first-rates, and has been content to take its doctrine from Lassalle. Karl Marx and Engels, the leaders of the German movement, and Bakounine and Prince Krapotkin, the Russian terrorists, have impressed their ideas deeply upon the French discontented ones. The revolt of the Commune of Paris after the Franco-German war was not exactly an Anarchist uprising, although the Anarchists impressed their ideas upon much of the work done. The Commune of Paris means very much the same as “the people of Illinois.” It is the legal designation of the commonwealth, and does not imply Communism any more than the word commonwealth does. It was a fight for the autonomy of Paris, and one in which many people were engaged who had no sympathy with Anarchy, although certainly the lawless element finally obtained complete control of the situation. The rising in Lyons several years later was distinctly and wholly anarchic, and it was for this that Prince Krapotkin and others were sent to prison.

At the present day there is no practical distinction between Socialism and Anarchy in France. All Socialists are Anarchists as a first step, although all Anarchists are not precisely Socialists. They look to the Russian Nihilists and the German irreconcilables as their leaders.

German Socialism is really the doctrine which is now taught all over the world, and it was this teaching that led directly to the Haymarket massacre in Chicago. It began with Karl Rodbertus, who lived from 1805 to 1875. He first became prominent in Germany in 1848, and he was for some time Minister of Education and Public Worship in Prussia. He was a theorist rather than a practical reformer, but competent critics assign to him the very highest rank as a political economist. His first work was “Our Economic Condition,” which was published in 1843, and his other books, which he published up to within a short time of his death, were simply elucidations of the principles he had first laid down. His writings have had a greater effect on modern Socialism than those of any other thinker, not even excepting Karl Marx or Lassalle. His theories were brought to a practical issue by Marx, who united into a compact whole the teachings of Proudhon and of Rodbertus, his own genius giving a new luster and a new value to the result. Marx is far and away the greatest man that the Socialism of the nineteenth century has produced. He was a deep student, a man of most formidable mental power, eloquent, persuasive,[23] and honest. His great book, “Capital,” has been called the Socialist’s Bible. Ely places it in the very first rank, saying of it that it is “among the ablest political economic treatises ever written.” And while the best scientific thought of the age agrees that Marx was mistaken in his premises and his fundamental propositions, there is accorded to him upon every hand the tribute which profound learning pays to hard work and deep thinking.

Coming from theory to practice brings us naturally from Marx to the International Society. It was founded in London in 1864 and was meant to include the whole of the labor class of Christendom. Marx was the chief, but he held the sovereignty uneasily. The Anarchists constantly antagonized him. Bakounine, the apostle of dynamite, opposed Marx at every point, and finally Marx had him expelled from the society. Bakounine thereupon formed a new Internationale, based upon anarchic principles and the gospel of force. The Internationale of which Marx was the founder has shrunk to a mere name, although the organization is still kept up, and the body with which the civilized world has now to reckon is that which Bakounine formed after his expulsion from the old body in 1872. It is a curious fact that many of the Socialists in Chicago to-day are enthusiastic admirers of Marx and at the same time members of the society and followers of the man Marx declared to be the most dangerous enemy of the modern workingman.

Marx is dead, however; many things are said in his name of which he himself would never have approved, and the “Red Internationale” proclaims the man a saint who refused either to indorse its principles or to consult with its leaders. It is the same as though, twenty years hence, the men who last year followed Barry out of the Knights of Labor were to hold up Powderly to the world as their law-giver and their chief.

Louise Michel, who was a very active worker in the radical cause during the outbreak of the Paris Commune, was born in 1830, and first attracted attention by verses full of force which she published very early in life. She was sentenced in 1871 to deportation for life, and was transported with others to New Caledonia. At the time of the general amnesty, in 1880, she returned to Paris, and became editor of La Révolution Sociale.

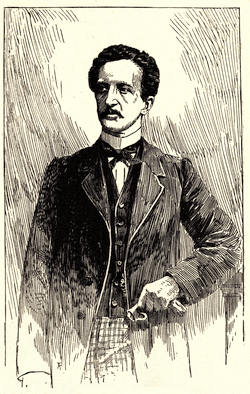

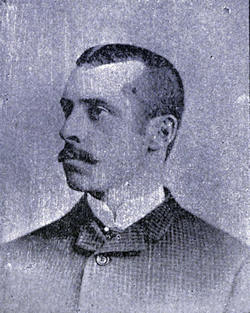

Ferdinand Lassalle, like Marx of Hebrew blood, and of early aristocratic prejudices, was the father of German Anarchy as it exists to-day. He was a deep student, and a remarkably able man. He took his inspiration from Rodbertus and from Marx, but applied himself more to work among the poor. Marx was over the heads of the common people. His “Capital” is very hard reading. Lassalle popularized its teachings. On May 23, 1863, a few men met at Leipsic under the leadership of Lassalle and formed the “Universal German Laborers’ Union.” This was the foundation of Social Democracy, and its teachings were wholly anarchic.[24] It aimed at the subversion of the whole German social system, by peaceful political means at first, but soon by force.

Lassalle was shortly afterwards killed in a duel over a love-affair, but he was canonized by the German Social Democrats as though his death were a martyrdom. Even Bismarck in the Reichstag paid a tribute to his memory. Lassalle died just about the time that a change was occurring in his convictions, and had he lived longer, and if contemporary history is to be believed, he would have taken office under the German Government and applied himself heartily to the building up of the Empire.

LOUISE MICHEL.

After Lassalle’s death the movement which he had initiated went forward with increased force. The German laborer was finally, as the Internationalists put it, aroused. The German Empire, following the example of the Bund, decreed universal suffrage in 1871. Before this, in Prussia especially, the laborer had but the smallest political influence. The vote of a man in the wealthiest class in Berlin counted for as much as the vote of fifteen of the “proletariat,” so called. Lassalle died in 1864, and suffrage was first granted in 1867. The Social Democrats at first were in close accord with Bismarck. It was the Social Democratic vote which elected Bismarck to the Reichstag in the first election after the suffrage was granted. In the fall of 1867 they sent eight members to the parliament of the Bund. In the elections after the formation of the Empire the Socialistic vote stood: In 1871, 123,975; in 1874, 351,952; in 1877, 493,288; in 1878, 437,158. The Social Democrats poll nearly 10 per cent of the whole vote of Germany at the present time.

In 1878 occurred the two attempts on the life of the Emperor of Germany described in a succeeding chapter, and the result was severe repressive measures against the Social Democrats. Their vote fell off, and their influence declined, but in the past two years, 1887 and 1888, they have more than recovered their past strength, and they now poll more votes and seem to exercise a greater political control in Germany than ever before.

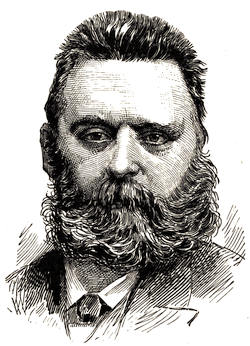

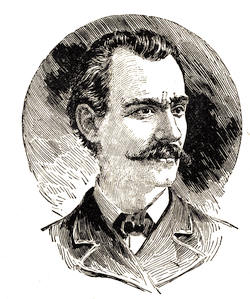

FERDINAND LASSALLE.

The passage of the “Ausnahmsgesetz,” the exceptional law against[25] German Socialists, drove many of them to this country, but had no effect in diminishing the propaganda in Germany. The result was an exodus of Socialists, or rather Anarchists, to America—by this time the two terms, wide apart as they may seem, had become one—and to Chicago came most of the irreconcilable ones. The American sympathizers, thus formed, at first fixed their attention upon the political situation in the old country, and they applied themselves closely to work in connection with the agitators who had not expatriated themselves. Money was sent in large quantities to the old country.

In Germany, in the meantime, the movement varied and shifted with each wind of doctrine; one president after another was tried and found wanting, until at last Jean von Schweitzer was chosen, and he guided the party until it was finally swallowed up in the organization perfected by Liebknecht and Bebel. Liebknecht was really but an interpreter of Marx, but he was honest, enthusiastic and devoted, and no man in the whole line of German political energy has left his name more thoroughly impressed upon the time. Out of these conditions and born of these ideas came the Anarchy which hurled the bomb whose crash at the Haymarket Square first aroused us to the work which is being done in our midst.

The Anarchists of Chicago are exotics. Discontent here is a German plant transferred from Berlin and Leipsic and thriving to flourish in the west. In our garden it is a weed to be plucked out by the roots and[26] destroyed, for our conditions neither warrant its growth nor excuse its existence.

The central idea of all Socialistic and Anarchic systems is the interference with the right of property by society. If we can convince ourselves that society has the right and the duty thus to interfere, then there is to be said nothing more. As long as the American citizen can buy his own land and raise his own crops, as long as average industry and economy will lead a man to competence, Socialism can only be like typhus fever—a growth of the city slums. There is no real danger in it. There is no peril which those charged with the protection of law and order are not ready to face, for every officer of the law that unreasonable discontent may menace is backed by the whole power of the republic; and the republic is founded upon principles which this alien revolt can neither harm nor affright.

There is a fact which, before I leave this chapter, I wish to bring home to the mind of every reader, and that is this:

The police of Chicago, like the police of every city in the Union, are actuated by no feeling of hostility to these people. We understand the genesis of their movement; we can put ourselves in their places and feel the things which actuate them; we are prepared to make as many excuses for them as they can make for themselves; we are ready to grant everything that they could claim, and more; but we see beyond this, and above this, facts which they forget and forego.

We have a government in these United States so firm and so elastic that it has every bulwark against either foreign or domestic attack, and yet it provides every opportunity to adjust itself to the will of the people.

The majority must rule, and does rule; but under our Constitution it rules only along lines decreed by the fathers long ago for the protection of the minority. There is a legal and constitutional means provided for every man to carry his theories of good government into actual practice. Every citizen has the right to vote, and to have his vote counted, and this right belongs to Anarchist and conservative, to radical and reactionist. There is no man can stand before the American people and say we have refused him his right: if it were done, the whole power of the Government would be marshaled to do him justice. When, then, we have provided every man with a means to impress his convictions upon the government of the country—when we have done everything that human ingenuity can do to secure a full and free expression of the popular will, as the final and supreme test upon every public question, we may be excused for refusing to let the Anarchists have their way. They are a minority of a minority, yet they would impose their system and their doctrine upon the majority. They would substitute for the ballot-box the dynamite bomb—for the will of the people the will of a contemptible rabble of discontents, un-American[27] in birth, training, education and idea, few in numbers and ridiculous in power.

Thus, while the police entertain no animosity against these men, we feel—I feel and every officer under my command feels—that we are bound by our oaths and by our loyalty to the State and to society to meet force with force, and cunning with cunning. We are the conservators of the law and the preservers of the peace, and the law will be vindicated and the peace preserved in spite of any and all attacks.

If our system is wrong, which I do not believe; if the principle that the majority of the citizens is to be ruled by an alien minority is to be accepted, which I do not accept, still there is the orderly and well-protected means provided by law, and guaranteed by the Government, to transform that idea into a governing fact. There is the ballot, free to every citizen, safe, satisfying, final. The men who try other methods are rushing to their own destruction. We pity them, we sympathize with them; but our duty is clear and manifest. We have a government worth fighting for, and even worth dying for, and the police feel that truth as keenly as any class in the community.

CHAPTER II.

Dynamite in Politics-Historical Assassinations—Infernal Machines in France—The Inventor of Dynamite—M. Nobel and his Ideas—The Nitro-Compounds—How Dynamite is Made—The New French Explosive—“Black Jelly” and the Nihilists—What the Nihilists Believe and What they Want—The Conditions in Russia—The White and the Red Terrors—Vera Sassoulitch—Tourgeneff and the Russian Girl—The Assassination of the Czar—“It is too Soon to Thank God”—The Dying Emperor—Two Bombs Thrown—Running Down The Conspirators—Sophia Perowskaja, the Nihilist Leader—The Handkerchief Signal—The Murder Roll—Tried and Convicted—A Brutal Execution—Five Nihilists Pay the Penalty—Last Words Spoken but Unheard—A Deafening Tattoo—The Book-bomb and the Present Czar—Strychnine-coated Bullets—St. Peter and Paul’s Fortress—Dynamite Outrages in England—The Record of Crime—Twenty-nine Convicts and their Offenses—Ingenious Bomb-making—The Failures of Dynamite.

THE attempt to gain political ends by an appeal to infernal machines is not a new one. It is as old as gunpowder—and the evangel of assassination is older still. Murder was the recognized political weapon of the Eastern and Western Empires, and the Chicago Anarchists have proved themselves neither better nor worse than the “old man of the mountain” or the Italian princes of the middle ages. During the reign of Mary Queen of Scots the mysterious explosion occurred in the Kirk of Feld in which Darnley lost his life. Somewhat later was the “gunpowder plot,” in which Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament. The petard and the hand-grenade were the grandfather and the grandmother of the modern bomb, and murderous invention came to its new phase in the infernal machine which Ceruchi, the Italian sculptor, contrived to kill Napoleon when First Consul—a catastrophe which was avoided by the fact that Napoleon’s coachman was drunk and took the wrong turn in going to the opera-house.

France was fertile in this sort of machinery. Some years later Fieschi, Morey and Pepin tried to kill Louis Philippe with a similar apparatus on the Boulevard de Temple. The King escaped, but the brave Marshal Mortier was slain. Orsini and Pieri made a bomb, round and bristling with nippers, each of which was charged with fulminate of mercury, to explode the powder within, meaning to assassinate the Emperor Napoleon and the Empress Eugenie.

In the year 1866, according to the most trustworthy authorities, dynamite was first made by Alfred Nobel. In speaking of the invention, Adolf Houssaye, the French litterateur, recently said:

It should be remembered that nine-tenths, probably, of the dynamite made is used in peaceful pursuits; in mining, and similar works. Indeed, since its invention great engineering achievements have been accomplished which would have been entirely impossible without it. I do not see, then, much room for doubt that it has on the whole been a great blessing[29] to humanity. Such certainly its inventor regards it. “If I did not look upon it as such,” I heard him say recently, “I should close up all my manufactories and not make another ounce of the stuff.” He is a strong advocate of peace, and regards with the utmost horror the use of dynamite by assassins and political conspirators. When the news of the Haymarket tragedy in Chicago reached him, M. Nobel was in Paris, and I well remember his expressions of horror and detestation at the cowardly crime.

“Look you,” he exclaimed. “I am a man of peace. But when I see these miscreants misusing my invention, do you know how it makes me feel? It makes me feel like gathering the whole crowd of them into a storehouse full of dynamite and blowing them all up together!”

Few people know what dynamite is, though it has attracted a good deal of attention of late, and before considering its use as a mode for political murder it may be well here to give an account of its making.

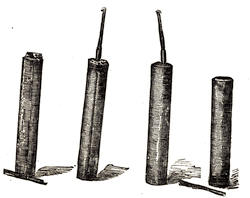

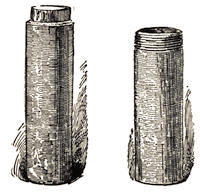

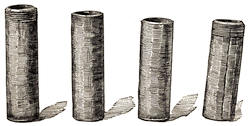

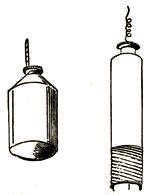

Nitro-glycerine, although not the strongest explosive known to science, is the only one of any industrial importance, as the others are too dangerous for manufacture. It was discovered by Salvero, an Italian chemist, in 1845. It is composed of glycerine and nitric acid compounded together in a certain proportion, and at a certain temperature. It is very unsafe to handle, and to this reason is to be ascribed the invention of dynamite, which is, after all, merely a sort of earth and nitro-glycerine, the use of the earth being to hold the explosive safely as a piece of blotting-paper would hold water until it was needed. Nobel first tried kieselguhr, or flint froth, which was ground to a powder, heated thoroughly and dried, and the nitro-glycerine was kneaded into it like so much dough. Of course, many other substances are now used, besides infusorial earth, as vehicles for the explosive—saw-dust, rotten-stone, charcoal, plaster of Paris, black powder, etc., etc. These are all forms of dynamite or giant powder, and mean the same thing. When the substance is thoroughly kneaded, work that must be done with the hands, it is molded into sticks somewhat like big candles, and wrapped in parchment paper. Nitro-glycerine has a sweet, aromatic, pungent taste, and the peculiar property of causing a violent headache when placed on the tongue or the wrist. It freezes at 40° Fahrenheit, and must be melted by the application of water at a temperature of 100°. In dynamite the usual proportions are 25 per cent. of earth and 75 per cent. of nitro-glycerine. The explosive is fired by fulminate of silver or mercury in copper caps.

Outside of the French arsenals it is to be doubted if anybody knows anything more about the new explosive, melinite, further than that it is one of the compounds of picric acid—and picric acid is a more frightful explosive than nitro-glycerine. I find in my scrap-book the following excerpt from the London Standard, describing the artillery experiments at Lydd with the new explosive which the British Admiralty has lately been examining. The Standard, after declaring that the experiments are “entirely satisfactory,” says:

The character of the compound employed is said to be “akin to melinite,” but its precise nature is not divulged. We have reason to believe that the “kinship” is very close. The details of the experiments which have lately been conducted at Lydd are known to very few individuals. But it is unquestionable that the results were such as demonstrate the enormous advantage to be gained by using a more powerful class of explosives than that which has been hitherto employed. There could be no mistake as to the destructive energy of the projectiles. Neither was there any mishap in the use of these terrible appliances. The like immunity was enjoyed at Portsmouth. A deterrent to the adoption of violent explosives for war purposes has consisted in the risk of premature explosion. But there is still the consideration that the advantage to be gained far exceeds the risk which has to be incurred. France has not neglected this question, and she is ahead of us. Her chosen explosive is melinite, and with this she has armed herself to an extent of which the British public has no conception. All the requisite materials, in the shape of steel projectiles and the melinite for filling them, have been provided for the French service and distributed so as to furnish a complete supply for the army and the navy. Whatever may be said as to the danger which besets the use of melinite, the French authorities are confident that they have mastered the problem of making this powerful compound subservient to the purposes of war. Concerning the composition of this explosive great secrecy is observed by the French Government, as also with regard to the experiments that are made with it. But Col. Majendie states that melinite is largely composed of picric acid in a fused or consolidated condition. Of the violence with which picric acid will explode, an example was given on the occasion of a fire at some chemical works near Manchester a year ago. The shock was felt over a distance of two miles from the seat of the explosion, and the sound was heard for a distance of twenty miles.

The conduct of the French in committing themselves so absolutely to the use of melinite as a material of war clearly signifies that with them the use of such a substance has passed out of the region of doubt and experiment. Their experimental investigations extended over a considerable period of time, but at last the stage of inquiry gave place to one of confidence and assurance. So great is the confidence of the French Government in the new shell that it is said the French forts are henceforth to be protected by a composite material better adapted than iron or steel to resist the force of a projectile charged with a high explosive. In naval warfare the value of shells charged in this manner is likely to be more especially shown in connection with the rapid-fire guns which are now coming into use. The question is whether the ponderous staccato fire of monster ordnance may not be largely superseded by another mode of attack, in which a storm of shells, charged with something far more potent than gunpowder, will be poured forth in a constant stream from numerous guns of comparatively small weight and caliber.

Combined with rapidity of fire, these shells cannot but prove formidable to an armor-clad, independently of any damage inflicted on the plates. The great thickness now given to ship armor is accomplished by a mode of concentration which, while affecting to shield the vital parts, leaves a large portion of the ship entirely unprotected. On the unarmored portion a tremendous effect will be produced by the quick-firing guns dashing their powerful shells in a fiery deluge on the ship.

Altogether the new force which is now entering into the composition of artillery is one which demands the attention of the British Government in the form of prompt and vigorous action. While we are experimenting, others are arming.

Dynamite, however, is the weapon with which the “revolution” has armed itself for its assault upon society. A terrible arm truly, but one difficult to handle, dangerous to hold, and certainly no stronger in their hands than in ours, if it should ever become necessary to use it in defense of law and order.

A number of Russian chemists, members of the Nihilist party, were the first to apply dynamite to the work of murder. It is to their researches that is to be credited the invention of the “black jelly,” so called, of which so much was expected, and by which so little was done.

Nihilist activity in Russia commenced almost as soon as the emancipated peasantry began to be in condition for the evangel of discontent. It was Tourgeneff, the novelist, who baptized the movement with its name of Nihilism—and the truth is that it is a movement rather than an organization. It is a loose, uncentralized, uncodified society, secret by necessity and murderous by belief; but it is a secret society without grips or passwords, without a purpose save indiscriminate destruction, and its very formlessness and vagueness have been its chief protection from the Russian police, who are, perhaps, after all is said and done, the best police in the world. A statement of Nihilism by that very famous Nihilist who is known as Stepniak, but who is suspected to be entitled to a much more illustrious name, runs thus:

By our general conviction we are Socialists and democrats. We are convinced that on Socialistic grounds humanity can become the embodiment of freedom, equality and fraternity, while it secures for itself a general prosperity, a harmonious development of man and his social progress. We are convinced, moreover, that only the will of the people should give sanction to any social institution, and that the development of the nation is sound only when free and independent and when every idea in practical use shall have previously passed the test of national consideration and of the national will. We further think that as Socialists and democrats we must first recognize an immediate purpose to liberate the nation from its present state of oppression by creating a political revolution. We would thus transfer the supreme power into the hands of the people. We think that the will of the nation should be expressed with perfect clearness, and best, by a National Assembly freely elected by the votes of all the citizens, the representatives to be carefully instructed by their constituents. We do not consider this as the ideal form of expressing the people’s will, but as the most acceptable form to be realized in practice. Submitting ourselves to the will of the nation, we, as a party, feel bound to appear before our own country with our own programme or platform, which we shall propagate even before the revolution, recommend to the electors during electoral periods, and afterwards defend in the National Assembly.

The Nihilist programme in Russia has been officially formulated thus:

First—The permanent Representative Assembly to have supreme control and direction in all general state questions.

Second—In the provinces, self-government to a large extent; to secure it, all public functionaries to be elected.

Third—To secure the independence of the Village Commune (“Mir”) as an economical and administrative unit.

Fourth—All the land to be proclaimed national property.

Fifth—A series of measures preparatory to a final transfer of ownership in manufactures to the workmen.

Sixth—Perfect liberty of conscience, of the press, speech, meetings, associations and electoral agitation.

Seventh—The right to vote to be extended to all citizens of legal age, without class or property restrictions.

Eighth—Abolition of the standing army; the army to be replaced by a territorial militia.

It must be remembered that the conditions in Russia are peculiar. The country is ruled by an autocracy; government is not by the people, but by “divine right.” The conditions which the English-speaking people ended at Runnymede still exist in Muscovy. There is neither free speech, free assembly, nor a free press, and naturally discontent vents itself in revolt. There is no safety-valve. Russia is full of generous, high-minded young men and women, who find their church dead, and their state a cruel despotism. They find themselves face to face with the White Terror, and they have sought in the Red Terror a relief. Flying at last from the hopeless contest, they have carried the hate of government born of bad ruling into Western Europe, and it is the infection of this poison that we have to deal with here. The average Russian Nihilist is a young man or a young woman—very often the latter—who, by the contemplation of real wrongs and fallacious remedies, has come to be the implacable enemy of all order and all system. Usually they are half-educated, with just that superficial smattering of knowledge to make them conceited in their own opinions, but without enough real learning to make them either impartial critics or safe citizens of non-Russian countries. We can pity them, for it is easy to see how step by step they have been pushed into revolt. But they are dangerous.

When one reads such a case as that which gave Vera Sassoulitch her notoriety, it is easier to understand Russia. General Trepoff, the Chief of Police of St. Petersburg, had arrested Vera’s lover on suspicion of high treason. The young man was by Trepoff’s order frequently flogged to make him confess his crime. Sassoulitch called on Trepoff and shot him. She was tried by a St. Petersburg jury and acquitted. Immediately a law was declared that no case of political crime should be tried by a jury, except when the Government had selected it. The arrest of the woman was ordered that she might be tried again under the new regulation, but in the meantime her friends had spirited her away.

A very similar crime was that attempted by another Nihilist heroine, Maria Kaliouchnaia, who attempted to kill Col. Katauski for his severity to her brother. In the assassination of the Czar, as I shall relate, a number of women were concerned, and their bravery was greatly more desperate than that of their male companions. The Russian woman is peculiar. I know no better picture of the “devoted ones” than that given in Tourgeneff’s “Verses in Prose”:

I see a huge building with a narrow door in its front wall; the door is open, and a dismal darkness stretches beyond. Before the high threshold stands a girl—a Russian girl. Frost breathes out of the impenetrable darkness, and with the icy draught from the depths of the building there comes forth a slow and hollow voice:

“Oh, thou who art wanting to cross this threshold, dost thou know what awaits thee?”

“I know it,” answers the girl.

“Cold, hunger, hatred, derision, contempt, insults, a fearful death even.”

“I know it.”

“Complete isolation and separation from all?”

“I know it. I am ready. I will bear all sorrows and miseries.”

“Not only if inflicted by enemies, but when done by kindred and friends?”

“Yes, even when done by them.”

“Well, are you ready for self-sacrifice?”

“Yes!”

“For anonymous self-sacrifice? You shall die, and nobody shall know even whose memory is to be honored?”

“I want neither gratitude nor pity. I want no name.”

“Are you ready for a crime?”

The girl bent her head. “I am ready—even for a crime.”

The voice paused awhile before renewing its interrogatories. Then again: “Dost thou know,” it said at last, “that thou mayest lose thy faith in what thou now believest; that thou mayest feel that thou hast been mistaken and hast lost thy young life in vain?”

“I know that also, and nevertheless I will enter!”

“Enter, then!”

The girl crossed the threshold, and a heavy curtain fell behind her.

“A fool!” gnashed some one outside.

“A saint!” answered a voice from somewhere.

With such material it was not difficult to build up the tragedy of 1881. Before the day of the Czar’s death came, there had been desperate attempts upon his life. Prince Krapotkin, a relative of the Nihilist of the same name, was murdered in February, 1879, and following this deed the terrorists applied themselves resolutely to the removal of the Emperor.

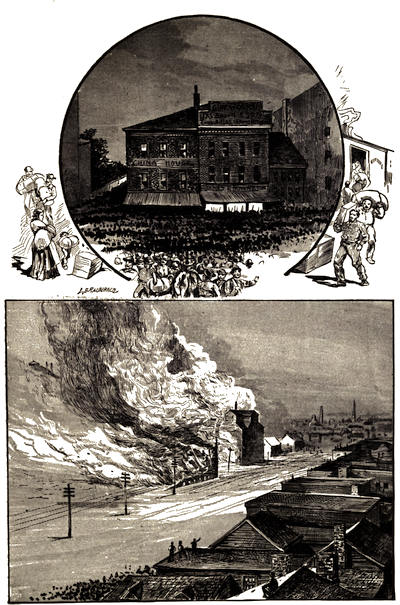

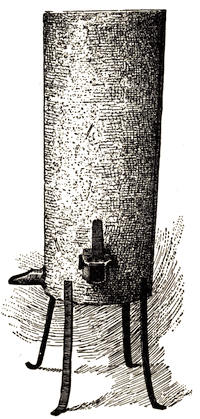

EXCAVATED DYNAMITE MINE IN MOSCOW.

For instance, in November, 1879, was the mine laid at Moscow. It was intended to blow up the railway train upon which the Czar was to enter the city, and for this purpose Solovieff and his comrades laid three dynamite mines under the tracks. Hartmann, who subsequently figured in the assassination, was one of the leaders, and here, too, was Sophie Peroosky, another of the regicides. They hired a house near the railway tracks and tunneled under the road amidst incredible difficulties and always in the most imminent danger. One hundred and twenty pounds of dynamite was in position, but the Czar passed by in a common train before the imperial[34] one on which he was expected, and his life was saved. On February 5, 1880, the mine under the Winter Palace was exploded; eleven persons were killed, but again the Czar escaped.

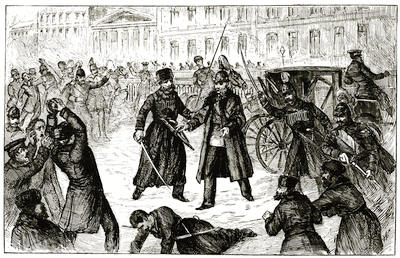

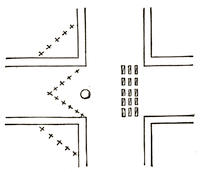

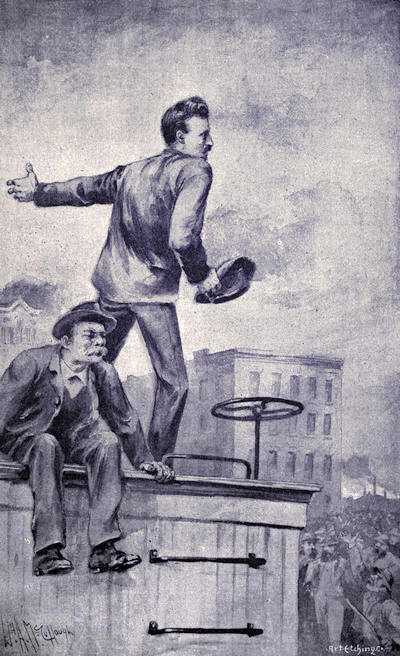

For some time before March 13, 1881, Gen. Count Loris Melikoff, the officer responsible for the safety of Czar Alexander II., had received disquieting reports which gave him the greatest anxiety. On the 10th of the month Jelaboff, the ringleader of the conspiracy, was arrested by accident, and the direction of the attempt on the Czar’s life was accordingly left to Sophie Perowskaja, a young, pretty and highly educated noblewoman, who had left everything to join the Nihilists. It is said that on the morning of the 13th Melikoff begged the Czar to forego his purpose of reviewing the Marine Corps, and keep within the palace. The Emperor laughed at him, and declared there was no danger. There was no incident until after the review. As the Emperor drove back beside the Ekaterinofsky Canal, just opposite the imperial stables, a young woman on the other side of the canal fluttered a handkerchief, and immediately a man started out from the crowd that was watching the passing of the Czar, and threw a bomb under the closed carriage. There was a roaring explosion, a cloud of smoke. The rear of the vehicle was blown away, and the horror-stricken multitude saw the Czar standing unhurt, staring about him. On the ground were several members of the Life Guard, groaning and writhing in pain. The assassin had pulled out a revolver to complete his work, but he was at once mobbed by the people. Col. Dvorjitsky and Captains Kock and Kulebiekan, of the guards, rushed up to their master and asked him if he was hurt.

“Thank God! no,” said the Czar. “Come, let us look after the wounded.”

And he started toward one of the Cossacks.

“It is too soon to thank God yet, Alexander Nicolaivitch,” said a clear, threatening voice in the crowd, and before any one could stop him, a young man bounded forward, lifted up both arms above his head, and brought them down with a swing. There was a crash of dynamite, a blaze, a smoke, and the autocrat of all the Russias was lying on the bloody snow, with his murderer also dying in front of him. Col. Dvorjitsky lifted up the Czar, who whispered:

“I am cold, my friend, so cold,—take me to the Winter Palace to die.”

The desperate Nihilist had thrown his bomb right between the Czar’s feet, and had sacrificed his own life to kill the Emperor.

Alexander was shockingly mutilated. Both of his legs were broken, and the lower part of his body was frightfully torn and mangled. The assassin—his name was Nicholas Elnikoff, of Wilna—was even more badly hurt. He died at once.

“IT IS TOO SOON TO THANK GOD!”

The Assassination of Czar Alexander II.

The Czar was taken into an open sled, and although it was claimed he received the last sacrament at the Winter Palace, most of those who know believe that he died on the way there.

In the meantime the police, with the utmost difficulty, rescued the first bomb-thrower from the maddened mob. The man, whose name proved to be Risakoff, coolly thanked the officers for preserving him, and then tried to swallow some poison which he had ready. In this he was foiled, and he was taken to prison.

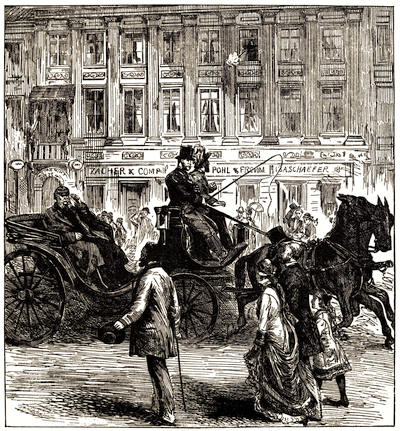

THE CZAR’S CARRIAGE AFTER THE EXPLOSION.

From a Photograph.

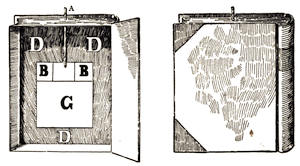

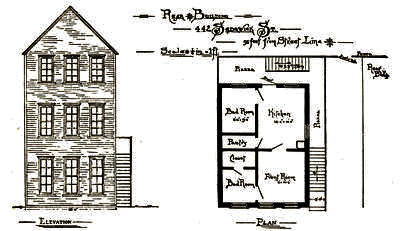

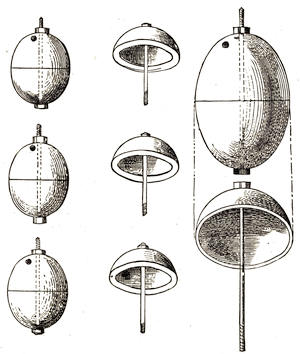

The infernal machine used by Elnikoff was about 7½ inches in height, and its construction is exemplified in the annexed diagram. Metal tubes (b b) filled with chlorate of potash, and enclosing glass tubes (c c) filled with sulphuric acid (commonly called oil of vitriol), intersect the cylinder. Around the glass tubes are rings of iron (d d) closely attached as weights. The construction is such that, no matter how the bomb falls, one of the glass tubes is sure to break. The chlorate of potash in that case, combining with the sulphuric acid, ignites at once, and the flames communicate over the fuse (f f) with the piston (e), filled with fulminate of silver. The concussion thus caused explodes the dynamite or “black jelly” (a) with which the cylinder is closely packed.

I said above that Jelaboff, the real leader of the conspiracy, had been arrested on the 10th. He was merely a suspect, and it was some time before the police realized what an important arrest had been made. Only two hours before the murder of the Emperor, Jelaboff’s house was searched, and there was found a great quantity of black dynamite, India rubber tubes, fuses and other articles. Jelaboff had been living here with a woman who was called Lidia Voinoff. This Lidia Voinoff was arrested on the Newsky Prospect, on March 22nd, and almost immediately identified as Sophia Perowskaja, the young woman who had given the handkerchief signal to the bomb-throwers, and who was wanted besides for the Moscow railway mine case. On the prisoner were found papers which led to the search of a house on Telejewskaia Street, where a man named Sablin committed suicide immediately on the appearance of the police, and a woman named Hessy Helfmann was arrested. A regular[37] Nihilist arsenal of black jelly, fuses, maps of different districts of St. Petersburg, with the Czar’s usual routes marked upon them, copies of papers from the secret press, etc., were found. While the police were still engaged in the search of the premises Timothy Mikhaeloff came in by accident. He was taken, and on him was found a copy of the new Czar’s proclamation, and penciled on the back were the names of three shops with three different hours in the afternoon. The officers descended on these places and gathered in customers, shop-keepers and everybody else about the place,—a process which brought in Kibaltchik, the Nihilist chemist and bomb-maker.