CONTENTS

I. PAUL, THE TELEGRAPH BOY.

II. THE CORTLANDT STREET FERRY.

III. OLD JERRY THE MISER.

IV. A STRANGE COMMISSION.

V. AN EXCITING INTERVIEW.

VI. PAUL MAKES A STRANGE DISCOVERY.

VII. PAUL RESOLVES TO MOVE.

VIII. PAUL MOVES TO LUDLOW STREET.

IX. PAUL BECOMES A CAPITALIST.

X. PAUL LOSES HIS BANK BOOK.

XI. AT THE SAVINGS BANK.

XII. JAMES BARCLAY’S DISAPPOINTMENT.

XIII. JAMES BARCLAY AT HOME.

XIV. ON THE TRACK OF NUMBER 91.

XV. BARCLAY GETS INTO BUSINESS.

XVI. AN UNEXPECTED MEETING.

XVII. A QUEER COMPACT.

XVIII. JAMES BARCLAY OBTAINS A CLEW.

XIX. OLD JERRY RECEIVES A VISIT.

XX. JAMES BARCLAY COMES TO GRIEF.

XXI. THE FANCY DRESS PARTY.

XXII. THE YOUNG MINSTRELS.

XXIII. THE PICKPOCKET.

XXIV. A ROOM AT THE ALBEMARLE HOTEL.

XXV. OLD JERRY’S WEALTH.

XXVI. ELLEN BARCLAY’S DISCOVERY.

XXVII. JERRY DISCOVERS HIS LOSS.

XXVIII. JERRY FINDS A NEW RELATION.

XXIX. A NEW COMMISSION.

XXX. PAUL’S RECEPTION AT ROCKVILLE.

XXXI. A DEFEAT FOR THE HOUSEKEEPER.

XXXII. FROST MERCER IS CONTRARY.

XXXIII. A STARTLING DISCOVERY.

XXXIV. A PLOT AGAINST PAUL.

XXXV. PAUL RETURNS TO NEW YORK.

XXXVI. JAMES BARCLAY REAPPEARS.

XXXVII. JAMES BARCLAY’S SCHEME.

XXXVIII. CONCLUSION.

Adventures of a Telegraph Boy

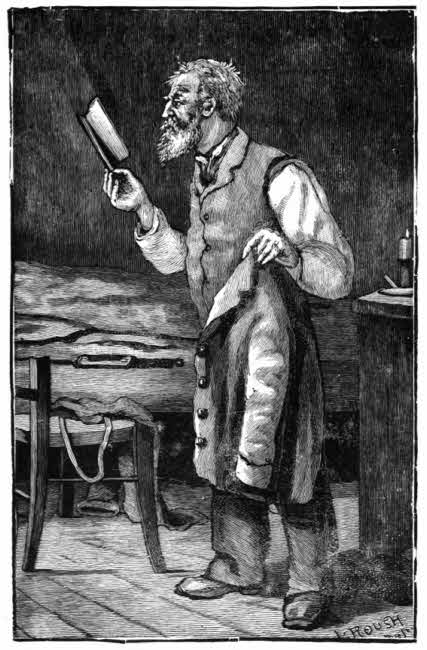

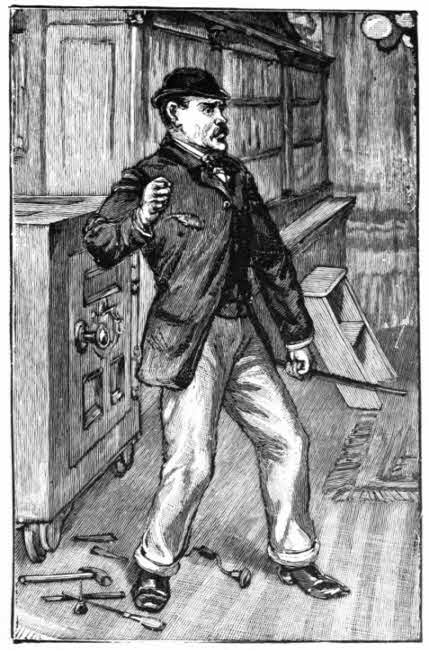

“FORTY DOLLARS!” EXCLAIMED OLD JERRY. “I’M IN LUCK FOR ONCE.”

By

Horatio Alger, Jr.

Author of

“Tom Tracy,” “Ned Newton,”

“Walter Griffith,” etc.

New York and Boston

H. M. Caldwell Company

Publishers

Copyright, 1889

By Frank H. Lovell & Co.

Copyright, 1900

By Street & Smith

Adventures of a Telegraph Boy

ADVENTURES OF A

NEW YORK TELEGRAPH BOY.

On Broadway, not far from the St. Nicholas Hotel, is an office of the American District Telegraph. Let us enter.

A part of the office is railed off, within which the superintendent has a desk, and receives orders for boys to be sent to different parts of the city. On benches in the back part of the office are sitting perhaps a dozen boys varying in age from fifteen to eighteen, clad in the well known blue uniform prescribed by the company. Each wears a cap on which may be read the initials of the company, with the boy’s number.

At the end of the benches sat a stout, well made boy, apparently sixteen years of age. He had a warm, expressive face, and would generally be considered good looking.

On his cap we read this inscription:

A. D. T.

91.

Some of the boys were smaller, two or three larger than Number 91. But among them all, he was the most attractive in appearance. The boys sat on the benches in patience waiting for a call from the superintendent.[6] They were usually selected in turn, but sometimes the fitness of a particular boy for the errand required was taken into consideration.

“Number 87!” called the superintendent.

A small boy of fifteen, but not looking over thirteen, left his seat and advanced to the desk.

“No, I don’t think you’ll do,” said the superintendent “There’s a man at the New England Hotel who wants a boy to go down with him to the Cortlandt Street Ferry, and carry his valise. A larger boy will be required.”

He glanced at the boys in waiting and called:

“Number 91!”

The boy of whom we have spoken rose with alacrity, and stepped up to the desk. He had been sitting on the bench for an hour, and was glad of an opportunity to go out on an errand.

The superintendent wrote on a card the name “D. L. Meacham, New England Hotel,” and handed it to the boy.

“Go at once to the New England Hotel, and call for that gentleman,” he said. “If he is not in, wait for him.”

“Yes, sir.”

Paul Parton, for this was his name, did not need any further directions. He was perfectly acquainted with the city, especially in the lower part, where he had lived for years. He crossed Broadway, and, taking an easterly course, made his way to the Bowery, on which, at the corner of Bayard Street, the New England Hotel stands. This is a very respectable inn, and by its fair accommodations and moderate prices attracts a large number of patrons.

Entering, Paul advanced to the desk.

“Is Mr. D. L. Meacham in?” he asked, referring to the card given him by the superintendent.

“Here he is!” replied, not the clerk to whom the[7] question was addressed, but a tall, elderly man with gray hair, clad in a rusty suit, evidently a gentleman from the rural districts.

“Are you the telegraph boy?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“I want to go down to the ferry to take the train to Philadelphia.”

“All right, sir. Is this your valise?” asked Paul, pointing to a shabby traveling bag that might, from its appearance, have been used by Noah when he was on board the ark.

“Yes, that’s mine.”

“Do you want to start now, Mr. Meacham?”

“Well, I might as well. I hain’t got nothing to keep me here. How fur is it?”

“About a mile. Perhaps a little more.”

Paul took the valise in his hand, and went out of the hotel, followed by the old man.

“Do you know the way all round here, sonny?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, it beats me. I get turned round, and don’t know where I am. If it wasn’t for that, I could have gone to the ferry alone. But land’s sake! I might wander all round till tomorrow morning without finding it.”

“Then I guess it’s better to have a boy with you,” said Paul, laughingly.

“You look like a smart boy,” said the old man, attentively examining Number 91. “Do you like your business?”

“Pretty well,” answered Paul.

“Is the pay pretty good?”

“I get four dollars a week.”

“That’s more than I got when I was your age, sonny.”

“It doesn’t go very far in the city, when you have[8] your board and clothes to pay for,” replied the young telegraph messenger.

“That’s so. I didn’t think of that. I was reared on a farm, where they didn’t make much account of the victuals you ate.”

“We have to make account of it here, sir.”

“So you don’t have much left out of your four dollars?”

“No, sir; but I get rather more than four dollars. Sometimes the gentlemen I am working for give me a little extra for myself.”

“How much does that come to—in a week?”

“Well, sometimes I make a dollar or two extra. It depends a good deal on whether I fall in with liberal gentlemen or not. I don’t mean this as a hint, sir,” added Paul, smiling. “I am not entitled to anything extra, but, of course, when it is offered I take it.”

Paul had a motive in saying this. He abhorred the idea of seeming to beg for a gratuity. Besides, judging from the appearance and rusty attire of the old man, he decided that he was poor, and could not afford to pay anything over the regular charges.

“I see,” said the old farmer, as Paul supposed him to be, with a responsive smile. “You’re right there, sonny. If you’re offered a little extra money, it’s all right to take it.”

By this time they had reached the City Hall Park, and were crossing it. Then, as now, the Park swarmed with bootblacks of all sizes, provided with the implements of their trade.

Frequently, in the rivalry which results from active competition, the little fellows are pushed aside, and the bigger and stronger boys take possession of the customers they have secured. There was a case of this sort which fell under the attention of Paul and his elderly companion.

A pale, delicate looking boy of twelve was signaled by a gentleman, a rod or two from the City Hall. He hastened eagerly to secure a job, but unhappily the signal had also been seen by a bigger boy, larger, if anything, than Paul, and he, too, ran to get in ahead of the smaller boy. Without ceremony, he put out his foot and tripped little Jack, and with a triumphant laugh sped on to the expectant customer. The little boy, who had been bruised by the fall, rose crying and disappointed.

“That’s mean, Tom Rafferty,” he said. “The gentleman called me.”

Tom only responded by another laugh. With him, might made right, and the dominating law was the will of the stronger.

“Oh, you’ll get another soon,” he said.

He got down on his knees, and placed his box in position. But all was not to be as smooth sailing as he expected. Paul, with a blaze of honest indignation, had seen the outrage. He was not surprised, for he knew both boys.

“Never mind, Jack,” he said. “I’ll fix it all right.

“Please mind the valise a minute, sir,” he added, and rather to the surprise of Mr. Meacham, he left him standing in the park, while he darted forward, seized Tom Rafferty by the collar, pulled him over backwards, and called, “Now, Jack!”

The little boy, emboldened by this unexpected help, ran up, and took Tom’s place at the foot of the customer.

“I’m the boy you called, sir,” he said.

“That’s true, my boy. Go ahead! Only be quick!” said the gentleman.

Tom Rafferty was furious.

“Don’t you know any better, you overgrown bully, than to get away little boys’ jobs?” asked Paul, indignantly.

“I’ll mash yer!” roared Tom.

“You mean if you can,” said the undaunted Paul.

“You think you’re a gentleman, just because you’re a telegraph boy. I could be a telegraph boy myself if I wanted ter.”

“Go ahead—I have no objection.”

“I’ll give that little kid the worst lickin’ he ever had, soon as he gets through, see ef I don’t.”

“Do it if you dare!” said Paul, his eyes flashing. “If you do, I’ll thrash you.”

“You dassn’t.”

“Remember what I say, Tom Rafferty. Now, Mr. Meacham, we’ll go on. I hope you’ll excuse me for keeping you waiting.”

“Yes, I will, sonny. It did me good to see you pitching into that young bully. I’d like to have done it myself.”

“I know both boys, sir. Little Jack is the son of a widow, who sews for a living, and she can’t make enough to support the family, and he has to go out and earn what he can by shines. He is small and weak, and the big boys impose upon him.”

“I’m glad he has some friends; Number 91, you’re a brave boy.”

“I don’t know about that, sir. But I can’t stand still and see a little kid like that imposed upon by a big brute like Tom Rafferty.”

They crossed Broadway, and presently neared Cortlandt Street. Just at the corner stood an old man, with bent form and white hair, dressed with extreme shabbiness. His hand was extended, and he was silently asking for alms.

Paul’s cheek flushed, and an expression of mortification swept over his face.

“Grandfather!” he said, reproachfully. “Please go home! Don’t beg in the streets. You make me ashamed!”

The old man turned, and, recognizing Paul, looked somewhat ashamed.

“I—I couldn’t help it,” he whined. “I’m so poor.”

“There is no need for you to beg. I’ll bring you some money tonight.”

“Just for a little while. See, a kind gentleman gave me that,” and he displayed a silver dime.

Paul looked very much annoyed.

“If you don’t stop begging, grandfather,” he said, “I won’t come home at all. I’ll go and sleep at the Newsboys’ Lodge.”

The old man looked frightened. Paul turned in every week two dollars and a half of his wages, and old Jerry had no wish to lose so considerable a sum.

“I’ll go—I’ll go right away,” he said, hastily.

“Be sure you do. If you don’t I shall hear of it, and you won’t see me any more.”

Just then a policeman of the Broadway squad, whose business it was to pilot passengers across through the maze of vehicles, took the old man in tow, and led him carefully across the great thoroughfare.

Mr. Meacham had watched in attentive silence this interview between Paul and the old man.

“So that is your grandfather,” he said.

“I call him so,” answered Paul, slowly.

“You call him so!” repeated his companion, puzzled. “Isn’t he really your grandfather?”

“No, sir; but as I have lived with him ever since I was very small, I have got into the habit of calling him so.”

“When did your father die?”

“When I was about six years old. He only left a hundred dollars or so, which Jerry took charge of, and took me to live with him. We were living in the same tenement house, and that’s how it came about.”

“Is he so very poor?”

“I used to think so,” answered Paul, “till one day I found out that he got a monthly pension from some quarter in the city. I don’t know how much it is, but I know he has money deposited in the Bowery Savings Bank.”

“How did you find that out, Number 91?”

“I was walking along the Bowery one day on an errand, when, as I was passing the bank, I saw grandfather going up the steps. That made me curious, and I beckoned to a friend of mine, Johnny Woods, and asked him to go in and see what the old man’s business appeared to be. I met Johnny that evening and he told me that he saw grandfather write out a deposit check and pay in money. I couldn’t find out how much it was, but Johnny said there were several bills in the sum.”

“Then your grandfather, as you call him, is a miser.”

“Yes, sir, that’s about what it comes to.”

“In what way does he live?”

“We have a poor, miserable room in a tenement on Pearl Street that costs us four dollars a month. Grandfather is always groaning about having to pay so much.”

“I suppose he doesn’t live very luxuriously?”

“Dry bread, and sometimes a little cheese, is what he lives on. Sometimes Mrs. O’Connor, an Irish[13] washerwoman, living in the room below, brings up a plate of meat out of charity.”

Paul uttered the last word bitterly, as if he felt keenly the mortification of the confession.

“But how can you look so well and strong on such fare?” asked the old farmer, gazing not unadmiringly at the red cheeks and healthy complexion of the young telegraph boy.

“I don’t take my meals with grandfather. He wanted me to hand in all my money, and share his meals, but I told him I should die in a week if I had to live like him, so he agreed to let me pay him two dollars and a half a week, and use the rest for myself. I generally eat at some restaurant on the Bowery.”

“But that must cost you more than a dollar and a half a week.”

“So it does, sir, but I get a dollar or two extra on fees from parties that employ me.”

“Even then, at the prices I paid at the New England Hotel, I shouldn’t think you could buy three meals a day.”

“What do you take me for, Mr. Meacham—a Vanderbilt or an Astor?” asked Paul, smiling. “I might as well go to Delmonico’s or the Fifth Avenue Hotel as to the New England House.”

“Where do you eat, then?”

“Generally at the Jim Fisk restaurant on Chatham Street.”

“Is that a cheap restaurant?”

“I can get a good breakfast there for eight cents, and a good dinner for eleven.”

Mr. Meacham looked surprised.

“What on earth can you get for those prices?” he asked.

“I can get a cup of coffee, eggs, fish balls, or mutton stew, with bread and butter, for eight cents,”[14] said Paul. “The coffee costs three cents, the other five. Then, for dinner, all kinds of meat cost eight cents a plate, and bread and butter thrown in.”

“That’s cheap enough certainly. Is it good?”

“It’ll do,” said Paul, briefly. “Last Sunday I got roast turkey. That cost twelve cents.”

“Great Scott!” ejaculated the farmer. “I never dreamed of how people live here in this great city.”

“You see we can’t all of us eat at Delmonico’s.”

“Did your grandfather ever eat at your restaurant?”

“Once I invited him, and told him I would pay the bill. He ate a square meal, meat, coffee, and pie, costing sixteen cents. He seemed to relish it very much, but when we were going away he groaned over my extravagance, and predicted that I would die in the poorhouse. I’ve never succeeded in getting him there since.”

“Well, well,” said the farmer, “of all the fools on the footstool, I believe the biggest is the man who deprives himself of vittles to save up money for somebody else to spend. I’m too selfish, for my part.”

“There isn’t a day that grandfather doesn’t groan over my foolish extravagance,” continued Paul. “Sometimes it makes me laugh, but oftener it makes me ashamed.”

“You don’t feel much attachment to him, then?”

“No, sir; perhaps I ought, as he has been my guardian so long, but you saw him yourself, sir—a poor, shabby, dirty old man! How can I feel attached to him?”

“I confess it must be hard.”

“You don’t think me much to blame, do you?”

“I don’t think you to blame at all. Affection must be natural, and there seems to be no ground for it in this case. But isn’t that the ferry?”

“Yes, sir.”

They crossed the street and entered the ticket office of the Cortlandt Street Ferry. Paul set down the valise, while Mr. Meacham secured a ticket.

“Now, Number 91,” said the old man, “how much do I owe you?”

Paul stated the sum, and Mr. Meacham put it in his hand.

“Thank you, sir,” said Paul, touching his cap.

“Stop a minute; here is something for yourself,” said his companion, taking out a silver dollar from his purse.

Paul regarded the old man with undisguised amazement.

“Are you surprised to get so much?” asked the old man with a smile.

“Yes, sir; I—” and he hesitated.

“You thought me a poor man, perhaps a mean man?”

“No, sir, not that; but I thought you not rich.”

“Don’t always judge by the clothes a man wears, Number 91. I own a large farm, and fifty thousand dollars in railroad stocks. That is rich for the country.”

“I don’t often get so much as this, sir.”

“I suppose not. But I have got a good deal of information out of you. I have heard much that surprised me, that I couldn’t have learned in any other way. So you are welcome to the dollar, and I think I have got my money’s worth.”

“I am very much obliged to you, sir.”

“That’s all right. Now, Number 91—by the way, what is your real name?”

“Paul Parton, sir.”

“Then, Paul, if you ever come my way, I should like to have you spend a week or a month on my[16] farm, as a visitor. I live in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, about a couple of miles from the city, and I’ll promise to give you enough to eat at less than you have to pay at the Jim Fisk restaurant.”

Paul thanked him with a smile, and turned to leave the ferry.

In the waiting room was a tall, bearded man, who looked something like a miner, as indeed he was, just returned from a long sojourn in California.

“Excuse me, boy,” he said, advancing towards our hero. “Do you mind telling me your name?”

“My name is Paul Parton,” answered the telegraph boy, with a glance of surprise.

“Were you ever in California?”

“Not that I know of, sir.”

“It’s strange!” said the miner, reflectively.

“What is strange, sir?”

“You are the living image of a man I used to know a dozen or fourteen years since in California. Were you born in New York?”

“I think so, sir—I don’t know.”

“Is your father living?”

“No, sir; I live with an old man who is not related to me.”

“Was your father ever in California?”

“He may have been, sir; but I was so young when he died that I don’t know much about his history.”

“What is that number on your cap?”

“I am Number 91, and work for the District Telegraph Company.”

“Number 91? Well, my boy, I hope you’ll excuse the liberty I took in addressing you. The California miners are rather unceremonious. I suppose you think it strange?”

“No, sir, not at all,” returned Paul, politely. “I am glad to have made your acquaintance.”

As he left the ferry, and lost sight of his questioner, he regretted that he had not at least inquired his name.

“He may have known my father,” thought Paul, “and I should be glad to meet some of his friends. I don’t think old Jerry knows much about him. I am getting tired of living with the old man, and should like to meet some relative or friend of whom I need not be ashamed.”

At six o’clock every other day Paul was let off from the office, other days he stayed much later.

On this particular day he was dismissed at six, and bent his steps homeward. He paused in front of a tall, shabby brick tenement house, unsightly in its surroundings, and abounding inside in unsavory smells, and took his way up the creaking staircase to a room on the fourth floor. He opened the door and entered.

The room was bare and cheerless in the extreme. The floor was uncarpeted, and if it had ever been painted it retained no vestiges of it. Two chairs, one broken, a small table which would have been dear at fifty cents, a low bedstead in one corner with a dirty covering—there were no sheets—and a small cot bed which Paul occupied—these were about all that could claim the name of furniture. There was, however, a wooden chest, originally a sailor’s, probably, which the telegraph boy used to hold the few extra clothes he possessed.

Old Jerry was sitting on one side of the bedstead.

“Good evening, grandfather,” said Paul, cheerfully.

“It isn’t a good ev’ning,” answered the old man, querulously. “I—I haven’t made a cent today.”

“I thought you got ten cents by begging,” said Paul.

“I—I forgot that. I might have got more if you[19] hadn’t interfered. You are very hard on your poor old grandfather, Paul.”

“I can’t bear to have you beg,” said Paul, his brows contracting. “I don’t want to have it said that I live with a beggar.”

“It isn’t my fault that I am very poor, Paul.”

“Are you so very poor?” asked Paul, pointedly.

“I—of course I am. What do you mean, Paul?” asked the old man, his manner indicating alarm. “Don’t you know I am very poor?”

“I know you say so.”

“Of course I am. Did any one ever tell you I wasn’t?”

“This room looks like it at any rate,” answered Paul, looking about with ill concealed disgust.

He didn’t choose to say anything of the discovery he had made, through his friend Johnny Woods, of old Jerry’s deposit in the Bowery Savings Bank.

“Yes, yes, and it is more than I can afford. Four dollars a month is an awful price. I have often thought I must find a cheaper room.”

“You couldn’t easily find a poorer one,” said Paul, moodily. “Well, grandfather, have you had your supper?”

“Yes, I have eaten a piece of bread.”

“That isn’t enough for you, grandfather. If you will come out with me I will get you some supper at the Jim Fisk restaurant.”

“No, no, Paul; I can’t afford it. It is sinful extravagance.”

“I can get you a cup of tea and some corn beef hash for eight cents. That isn’t much. Don’t you think you would enjoy a cup of tea?”

“Yes, Paul, it would do me good, if I could afford it.”

“But I will pay for it.”

“Oh, Paul, you will die in the poorhouse if you[20] are so wasteful. The money that you have spent at that eating house would bring joy to the heart of your old grandfather.”

“Look here,” said Paul, who could not bring his mind to calling the old man grandfather, as he had often done before. “It’s no use talking. You may starve yourself if you want to, but I don’t mean to. I’m going out to supper now. If you go with me I’ll pay for your supper, and it shan’t cost you a cent. I am sure you would like a good cup of tea.”

For an instant an expression of longing crept over the face of the old miser, but it was soon succeeded by a look of cunning and greed.

“It would cost eight cents, wouldn’t it, Paul?” he said.

“Yes, but that isn’t much. If you’d like a plate of roast beef and a cup of tea, I’ll buy it for you. They will cost only eleven cents. So put on your hat, and we will go out together.”

“Wait a minute, Paul,” said the old man. “Would you mind giving me the money instead—eleven cents?”

“No, I don’t mind, but I would rather you would go out with me. How do you expect to keep soul and body together without anything but dry bread and cold water?”

“I’m so poor, Paul; I can’t afford anything better,” whined old Jerry.

“I see it’s no use talking to you,” said Paul, in a vexed tone. “Well, if you prefer to have me give you the money, here it is.”

He took from his pocket a dime and a penny, and passed it over to the old man.

Old Jerry chuckled, and a smile crept over his wrinkled features, as he eagerly clutched the coins.

“Good boy, Paul!” he said. “That’s right, to be kind to your poor old grandfather.”

“Well, I’m going out to supper,” said Paul, abruptly, for it was painful to him to witness this evidence of the old man’s infatuation. “I’ll be back soon.

“That’s a guardian to be proud of,” he said, bitterly, as he made his way carefully down the rickety staircase. “Who can blame me for not liking him? I don’t believe I can make up my mind to call him grandfather again. After all, why should I? He is no relation of mine, and I am glad of it.”

The life of a telegraph boy is full of variety and excitement. He never knows when he goes to the office in the morning on what errands he may be sent, or what duties he may be called upon to discharge. He may be sent to Brooklyn, or Jersey City, with a message—sometimes even farther away. He may be detained to supply the place of an absent office boy, or sent up town to go out and walk with a child. In the evening he may be directed to accompany a lady to the theater as escort. These are a few of the uses to which telegraph messenger boys are put.

Of course Paul had had his share of varied commissions. But the day after that on which our story opens, a new duty awaited him.

It was about five o’clock that the superintendent called “Number 91.”

“Yes, sir,” answered Paul, promptly.

“You are to go up to No. ——, West Fifty First Street, to spend the night.”

Paul looked surprised.

“To spend the night?” he repeated.

“Yes, the head of the household has been called away for a day or two, and there is no man in the house. Mrs. Cunningham is timid, and has sent for a boy to protect the house against possible burglars.”

The superintendent smiled, and so did Paul.

“I guess I can do it,” he said.

“Very well, you will report at the house about seven o’clock.”

“Can I go home and tell grandfather? He might be alarmed if I didn’t come home.”

“Yes; I will give you an extra half hour for supper.”

At seven o’clock Paul rang the bell of a handsome brown stone mansion on West Fifty First Street.

The door was opened by a servant girl.

“I was sent for by Mrs. Cunningham,” said Paul.

“Yes, the missis is expecting you. Come right in!”

Paul observed, as he followed the girl upstairs into a sitting room on the second floor, that the house was very handsomely furnished—and came to the natural conclusion that the occupants were rich.

“Just take a seat, and I’ll tell the missis,” said the girl.

Paul sat down in a plush covered arm chair, and looked about him admiringly. “I wonder how it must seem to live in such a house as this,” he reflected. And then his thoughts went back to the miserable tenement house in which he and his grandfather lived, and he felt more disgusted with it than ever, after the sight of this splendor.

His reflections were interrupted by the entrance of a pleasant faced lady.

“Are you the boy I sent for?” she asked, with a smile.

“Yes, ma’am,” answered Paul, respectfully, rising as he spoke.

“I suppose you know why I want you,” proceeded the lady.

“Yes, ma’am; I was told there were only ladies in the house, and you wanted a man to sleep here.”

“I am afraid you can hardly be called a man,” said the lady with another smile. “Still you are not a woman or girl, and I shall feel safer for having you[24] here. I am afraid I am a sad coward. What is your name?”

“Paul—Paul Parton.”

“That is a nice name.”

“My husband has been called to Washington,” she added, after a pause, “and will be absent possibly ten nights. Knowing my timidity, he recommended my sending for a messenger boy. I may say, however, that I have some reason for alarm. Two houses in this block have been entered at night within a month. Besides, through a thieving servant, who was probably a confederate of thieves, it has become known that we keep some valuables in a safe in the library, and this may prove a temptation.”

At this moment an extremely pretty girl of fourteen entered the room, and looked inquiringly at Paul.

“Jennie,” said Mrs. Cunningham, “this is Paul Parton, who is to protect and defend us tonight, if necessary.”

Jennie regarded Paul with a smile.

“Won’t you be afraid?” she asked.

“No, miss,” answered Paul, who was instantly impressed in favor of the pretty girl whose acquaintance he was just making.

“I’m not easily frightened,” he answered.

“Then you’re different from mamma and me. We are regular scarecrows—no, that isn’t the word. I mean we are regular cowards. Still, with a brave and strong man in the house,” she added, with an arch smile, “we shall feel safe.”

“I hope you will be,” said Paul

“It is still early,” said Mrs. Cunningham. “Have you had your supper, Paul?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“We shall not retire before ten—Jennie, you can entertain this young gentleman, if you like.”

“All right, mamma—if I can—that is, if he isn’t hard to entertain. Do you play dominoes, Paul?”

“Yes, miss.”

“O, don’t call me miss—I don’t mind your calling me Jennie.”

The two sat down to a game of dominoes, and were soon on the friendliest possible terms.

After a while, seeing a piano in the room, Paul asked the young lady if she played.

“Yes; would you like to hear me?”

“If you please.”

After three or four pieces, she asked—“Don’t you sing?”

“Not much,” answered Paul, bashfully.

“Sing me something, won’t you?”

Paul blushed, and tried to excuse himself.

“I don’t sing any but common songs,” he said.

“That’s what I want to hear.”

After a while Paul mustered courage enough to sing “Baby Mine,” and another song which he had heard at Harry Miner’s.

They were not classical, but the young lady seemed to enjoy them immensely. They were quite unlike what she had been accustomed to hear, and perhaps for that reason she enjoyed them the more.

“I think you sing splendidly,” she said.

Of course Paul blushed, and put in a modest disclaimer. Still he felt pleased, and decided that Jennie Cunningham was the nicest girl he had ever met.

“But what would she say,” he thought, “if she could see the miserable place I live in?” and the perspiration gathered on his face at the mere thought.

At ten o’clock Mrs. Cunningham suggested that it was time to go to bed.

“Paul, you will sleep in a little bedroom adjoining the library,” she said.

“All right, ma’am.”

“Come with me and I will show you your bedroom.”

It was a pleasant room, though small, and seemed to Paul the height of luxury.

“Shall I leave with you my husband’s revolver?” asked the lady.

“Yes, ma’am, I would like it.”

“Do you understand the use of revolvers?”

“Yes; I have practiced some with them in a shooting gallery.”

“I hope there will be no occasion to use it. I don’t think there will. But it is best to be prepared.”

Paul threw himself on the bed in his uniform in order to be better prepared to meet any midnight intruder.

“It won’t do to sleep too sound,” he thought, “or the house might be robbed without my knowing it.”

He was soon fast asleep. It might have been because he had the matter on his mind that about midnight he woke up. A faint light had been left burning in the chandelier in the library. Was it imagination on Paul’s part that he thought he heard a noise in the adjoining room? Instantly he was on the alert.

“It may be a burglar!” he thought, with a thrill of excitement.

He got up softly, reached for the revolver, and with a stealthy step advanced to the door that opened into the library.

What he saw was certainly startling.

A man, tall and broad shouldered, was on his knees before the safe, preparing to open it.

“What are you doing there?” demanded the telegraph boy, firmly.

THE INTERRUPTED BURGLAR.—See page 27.

The man sprang to his feet, and confronted Paul[27] standing with a revolver in his hand pointed in his direction.

“O, it’s a kid!” he said, contemptuously.

“What are you doing there?” repeated Paul.

“None of yer business! Go back to bed!”

“Leave this house or I fire!”

The man thought of springing upon the boy, but there was something in his firm tone that made him think it best to parley. A revolver, even in a boy’s hand, might prove formidable.

“Go to bed, or I’ll kill you!” said the burglar, with an ugly frown.

“I will give you two minutes to leave this room and the house!” said Paul. “If you are here at the end of that time I fire!”

There was an expression of baffled rage on the face of the low browed ruffian as he stood bending forward, as if ready to spring upon the undaunted boy.

For a full minute Paul and the burglar faced each other without either moving. The telegraph boy of course waited for some aggressive movement on the part of his opponent. In that case he would not hesitate to fire. He felt the reluctance natural to any boy of humane instincts to take human life, and resolved, if possible, only to disable the ruffian. His heart quickened its pulsations, but in manner he was cool, cautious and collected. If the burglar had seen any symptoms of timidity or wavering, he would have sprung upon Paul. As it was, he was afraid to do so, and was enraged at himself because he felt cowed and intimidated by a boy. He resolved to inspire fear in Paul if he could.

“I have a great mind to kill you,” he growled.

“Two can play at that game,” said Paul, undaunted.

“Look here! You are making a fool of yourself. You are risking your life for nothing.”

“I am only doing my duty,” said Paul, firmly.

“The kid’s in earnest,” thought the burglar. “I must try him on another tack.

“Look here,” he said, changing his tone. “You are a poor boy, ain’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Just you lower that weapon, and don’t interfere with me, and I will make it worth your while.”

“What do you mean?” asked Paul, who, however, suspected the burglar’s meaning.

“I mean this,” said the intruder, in an insinuating tone. “Let me open the safe and make off with the contents, and I’ll give you a liberal share of it.”

“What do you take me for?” demanded Paul, indignantly.

“For a boy, of course. What do you care for the people in the house? They are rich and can afford to lose what will make us rich. Let me know where you live, and I’ll deal squarely with you. I mean it. All you’ve got to do is to go back to bed, and they’ll think you slept through and didn’t see me at all. What do you say?”

“I say no a thousand times!” answered Paul, boldly. “I may be poor all my life long, but I won’t be a thief.”

The burglar’s face expressed the rage he felt. It was very hard for him to resist the impulse to spring upon Paul, but the resolute mien of the boy satisfied him that it would be very dangerous.

“You refuse then?” he said, sullenly.

“Yes; you insult me by your proposal.”

“I wish I had brought a pistol; then you wouldn’t have dared speak to me in that way.”

Paul was relieved to hear this. He had concluded that the burglar was unarmed, but didn’t know it positively. Now he could dismiss all fear.

“Well,” he said, “are you going?”

The burglar eyed our hero during a minute of indecision, and decided that his plan was a failure. He certainly could not open the safe within range of a loaded revolver, and should he attack Paul, would not only risk his life, but rouse the house, and fall into the hands of the police, a class of men he made it his business to avoid. It was a bitter pill to swallow, but he must submit.

“Will you promise not to shoot if I agree to leave the house?”

“Yes.”

“Will you promise not to start the burglar alarm, but allow me to escape without interference?”

“Yes, if you will agree never to enter this house again.”

“All right!”

“You promise?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Then I’ll go. If you break your word, boy, you’ll wish you had never been born,” he added, fiercely. “I’d hunt you night and day after I got out of jail, and kill you like a dog.”

“You need not be afraid. I will keep my word.” There was something in Paul’s tone and manner that inspired confidence.

“You ain’t a bad sort!” said the burglar, paying an involuntary tribute to the boy’s staunch honesty. “You’re a cool kind of kid, any way. What an honor you’d make to our profession!”

Paul could not help smiling.

“I suppose that’s a compliment,” he said. “Thank you. Now I must trouble you to go.”

“I’m going! Remember your promise!”

In an instant the burglar was out of the window, through which he had made his entrance, and disappeared from sight. Paul did not approach the window, lest his doing so should excite alarm in the rogue. When a sufficient time had elapsed he ran to the window, closed it, and once more breathed freely. The danger was passed, and he began now to feel the tension to which his nerves had been subjected.

“Has anything happened, Paul?” asked a voice. Turning, Paul saw Mrs. Cunningham at the door. She had thrown a wrapper over her, and, attracted by the sound of voices, had entered the library.

“Has any burglar been here?” she asked, nervously, observing Paul with the revolver in his hand.

“Yes,” answered the telegraph boy; “I have just bidden the gentleman good night.”

By this time Jennie, too, made her appearance. “What is it, mamma? What is it, Paul?” she asked. “Why are you standing there with the revolver in your hand?”

Paul told the story as briefly as the circumstances would admit.

“It was a mercy you were awake!” said Mrs. Cunningham. “Did you hear the noise of the man’s entrance?”

“I don’t know how I happened to wake up,” said Paul. “I generally sleep sound. But I opened my eyes, and immediately heard a noise in this room.”

“But did you have time to dress?” asked Jennie.

“I did not need to do so, for I threw myself on the bed with my clothes on.”

“And with your cap on?” inquired Jennie with an arch smile.

“No, but when I rose from the bed I put it on without thinking. I don’t know whether I ought to have let the burglar get off free, but I thought it the easiest way to avoid trouble.”

“You did right. I approve your conduct,” said Mrs. Cunningham. “You seem to have acted with remarkable courage and discretion.”

“I am very glad if you are pleased, madam,” said Paul, gratified at this cordial indorsement.

“Weren’t you awfully scared, Paul?” asked Jennie Cunningham.

“Well, I was a little scared, I admit,” answered Paul, with a smile, “but I didn’t think it wise to show it before the burglar.”

“My hand would have trembled so that I couldn’t hold the pistol,” declared the young lady.

“Of course; you are a girl, you know.”

“Don’t you think girls are brave, then?”

“They are not called upon to be brave in the same way.”

“A good answer,” said Mrs. Cunningham. “And now, Jennie, we had better go back to bed. Will you not be afraid to sleep here the rest of the night after this adventure?” she asked, turning to Paul.

“No, Mrs. Cunningham. The burglar won’t feel like coming back.”

“What’s that?” asked Jennie, pointing to some article on the floor.

“It is the burglar’s jimmy,” said Paul, stooping to pick it up. “He left in such a hurry that he forgot to take it with him. I will carry it into my room, and take care of it.”

Paul bade the two visitors good night and threw himself once more on the bed. The remainder of the night passed quietly. The midnight visitor did not reappear.

The next morning Mrs. Cunningham insisted on Paul’s taking breakfast with her before he returned to the telegraph office. Though it was a new experience to Paul sitting down at a luxuriously furnished table, in a refined family, he was possessed of a natural good breeding, which enabled him to appear to advantage.

He was flattered by the cordial manner in which Mrs. Cunningham and her daughter treated him, and he was tempted to ask himself whether he was the same boy that had lived for years in a squalid tenement house, under the guardianship of a ragged and miserly old man. Being gifted with a “healthy appetite,” Paul did not fail to appreciate the dainty rolls, tender meat, and delicious coffee with which he was served.

“I can’t get such a breakfast as this at the ‘Jim Fisk’ restaurant,” thought Paul. “Still, that is a good deal better than I could get at home.”

“I am not sure whether I shall need you tonight, Paul,” said Mrs. Cunningham, as they rose from the breakfast table. “It is not certain whether Mr. Cunningham will be at home or be detained over another night at Washington.”

“I shall be glad to come if you need me,” said Paul.

“I think I will have you come up, at any rate,[34] about seven o’clock,” said the lady. “I will write a line to the superintendent to that effect.”

“Very well, ma’am.”

When Paul presented himself at the office he was the bearer of a note to the superintendent.

That official showed some surprise as he read it.

“So you drove away a burglar, Number 91?” he said.

“I believe I frightened him away,” answered Paul.

“Humph! Was he a little fellow?”

“No, a large man.”

“And he was afraid of you?” continued the superintendent, surprised.

“He was afraid of my revolver,” amended Paul.

The superintendent asked more questions, being apparently interested in the matter.

“The lady wishes you to go up again tonight,” he said.

“Yes, sir, so she told me, but it is not certain that I shall have to stay all night.”

“Of course you are to go.”

As the telegraph office would receive a good round sum for Paul’s services, the superintendent was very willing to send him up.

At noon Paul went home.

The tenement house seemed still more miserable and squalid, as he clambered up the rickety staircase. He mentally contrasted it with the elegant mansion in which he had spent the night, and it disgusted him still more with the wretched surroundings of the place he called home.

He was about to open the door of old Jerry’s room, when he was arrested by the sound of voices. Jerry’s, high pitched and quavering, was familiar enough to him, but there seemed something familiar, also, in the voice of the other, and yet he could not identify it with any of Jerry’s acquaintances.

There was a round hole in the door, the origin of which was uncertain, and Paul, knowing that he was at liberty to enter, did not think it wrong to reconnoiter through it before doing so.

To his intense surprise, the face of the visitor, visible to him through the opening, was that of the burglar whom he had confronted the night before.

“What can he have to do with Jerry?” Paul asked himself, in bewilderment.

Just then the man spoke.

“The fact is, father, I am hard pressed, and must have some money.”

Paul’s amazement increased. Was this burglar the son of old Jerry? He remembered now having heard Jerry refer to a son who had left him many years ago, and who had never since been heard of.

“I have no money, James,” whined the old man. “I am poor—very poor.”

“I’ve heard that talk before,” said the son, contemptuously; “and I know what it means.”

“But I am poor,” repeated old Jerry, eagerly. “I don’t get enough to eat. All I can afford is bread and water.”

“How much money have you got in the bank?” asked James.

“Wh—what makes you ask that?” asked the old man, in an agitated voice.

“Ha! I have hit the nail on the head,” said the visitor with an unpleasant laugh.

“You see how poor I am,” said the old man. “Does this poor room look as if I had money?”

“No, it doesn’t, but I know you of old, father. I suppose you are the same old miser you used to be. I shouldn’t wonder if you could raise thousands of dollars if you chose.”

“Hear him talk!” ejaculated the old man, raising his feeble arm in despairing protest. “I—I haven’t[36] got any money except a few cents that Paul brought me yesterday.”

“And who is Paul?” asked the son, quickly.

“He is a boy I took years ago when he was very small. I—I took him out of charity.”

“Very likely. That’s so like you,” sneered the son. “I warrant you have got more out of him than he cost you.”

This was true enough, as Paul could testify. He was only six when he came under the old man’s care, but even at that tender age he was sent out on the street to sell papers and matches, and old Jerry tried to induce him to beg; but that was something the boy had always steadfastly refused to do.

He had an independent, self respecting spirit, which made him ashamed to beg. He was always willing to work, and to work hard, and he generally had an opportunity to do so. This will relieve Paul from the charge of ingratitude, for he had always paid his own way, and really owed Jerry nothing.

“He—he has cost me a great deal,” whined Jerry, “but I knew his father, and I could not turn him out into the streets.”

“And how old is this boy now?” asked the son.

“I—I think he is about sixteen.”

“He ought to be able to earn something. What does he do?”

“He is a telegraph boy.”

“Ha!” exclaimed the burglar with a scowl, for the word provoked disagreeable memories of the previous night. “I hate telegraph boys.”

“Paul is a good boy—a pretty good boy, but he eats a sight.”

The son indulged in a short laugh.

“How does he like your boarding house?” he asked.

“He doesn’t eat here; he goes to a restaurant. He spends piles of money!” groaned the old man.

“Telegraph boys are not generally supposed to revel in riches,” said the son in a sarcastic tone. “It’s so much out of your pocket, eh?”

“Yes,” groaned the old man. “If he would give me all his wages I should be very comfortable.”

“But he wouldn’t. From what I know of your table, father, I think he would starve to death in a month. I haven’t forgotten how you starved me when I was a kid.”

“You look strong and well now,” said old Jerry.

“Yes, but no thanks to you! But to business! How much money have you got?”

“Very little, James. I have eleven cents that Paul gave me yesterday.”

“Bah! You are deceiving me. Where is your bank book?”

“I have none. What makes you ask such questions?” demanded the old man, querulously. “I wish you would go away.”

“That is a pretty way to treat a son you haven’t seen for twelve years. Do you know what I am?”

“No.”

“Then I’ll tell you; for years I have been a burglar.”

Old Jerry looked frightened.

“You’re not in earnest, James?”

“Yes, I am. I ain’t proud of the business, but you drove me to it.”

“No, no,” protested the old man.

“You made me work hard, and half starved me when I was a boy, you gave me no chance of education, and all to swell your paltry hoards. If I have gone to the bad, you are responsible. But let that drop. I’ve been unfortunate, and I want money.”

“I told you I had none, James.”

“And I don’t believe you. Hark you! I will[38] come back tomorrow,” he said, with a threatening gesture. “In the meanwhile, get fifty dollars from the bank, and have it ready for me. Do you hear?”

“You must be mad, James!” said old Jerry, regarding his son with a look of fear.

“I shall be, unless you have the money. I will go now, but I shall be back tomorrow.”

Paul ran downstairs hastily, as he heard the man’s heavy step approaching the door. He didn’t care to be recognized by his unpleasant acquaintance of the night previous.

After Jerry’s unwelcome visitor was well out of the way, Paul returned to the room. He found old Jerry trembling and very much distressed. The old man looked up with startled eyes when he opened the door.

“Oh, it’s you, Paul,” he said, in a tone of relief.

“Who did you think it was?” asked Paul, wishing to draw out the old man.

“I—I have had a visit from a bad man, who wanted to rob me.”

“Who was it?”

“I’ll tell you, Paul, but it’s a secret, mind. It was my son.”

“I didn’t know you had a son.”

“Nor I. I thought he might be dead, for I have not seen him for twenty years. I am afraid he is very wicked.”

“How did he find you out?”

“I don’t know. He—he frightened me very much. He wanted me to give him money—and I so miserably poor.”

Paul didn’t answer.

“You know how poor I am, Paul,” continued the old man appealingly.

“You always say so, Jerry.”

The old man did not appear to notice that Paul had ceased to call him grandfather.

“And it’s true—of course it’s true. But he wants me to pay him fifty dollars. He is coming back tomorrow.”

“But he can’t get it if you haven’t it to give.”

“I—I don’t know. He was always bad tempered—James was. I am afraid he might beat me.”

“What! Beat his father!” exclaimed Paul, indignantly.

“He might,” said the old man. “He wasn’t a good boy like you. He always gave me trouble.”

“Are you really afraid he will come, grand—Jerry?” asked Paul, earnestly.

“Yes, he is sure to come—he said so.”

“Then I think we had better move to another place where he can’t find us.”

“Yes—yes—let us go,” said the old man, hurriedly. “But, but,” he added, with a sudden thought, “we have paid the rent here to the end of the month. I can’t afford to lose that—I am so poor.”

“It will only be a dollar and a half; I will pay it,” said Paul.

“Then I think I shall go. When shall we leave, Paul?”

“This evening, Jerry, if I can get the time. I may have to stay up town to guard a house where the gentleman is absent, but it isn’t certain. If I do, I will be here early in the morning, before I go to work.”

This assurance seemed to abate the apprehensions of the old man, who, it was evident, stood in great fear of his son. Paul was obliged to take a hurried leave of him in order to have time for lunch before returning to the office.

“Who would have dreamed,” he said to himself, “that the bold burglar whom I encountered last night, was the son of old Jerry? One is as timid as a mouse, the other seems like a daring criminal. I[41] wonder why Jerry never told me that he had a son.”

The discovery that Jerry had such a son made Paul still more unwilling to own a relationship to him. It was bad enough to pass for the grandson of a squalid miser, but it was worse to be thought the son or nephew of a burglar.

The day passed quietly. Paul was not sent out much, on the supposition that he might have to pass another night at the house of Mr. Cunningham.

About seven o’clock he rang the bell of the house in Fifty First Street.

The same servant admitted him. This time she received him with a smile, knowing that he stood high with her mistress.

“Come right in,” she said. “The mistress will see you in the sitting room.”

“Have you had any more visits from burglars?” asked Paul.

“No; may be they’re waiting till night.”

“Has Mr. Cunningham got back?”

“No, but he’s expected at eight.”

Paul was glad to hear this, for he preferred not to remain over night, as he knew that old Jerry would need him.

When Paul entered the sitting room Mrs. Cunningham received him cordially.

“I suppose you have not seen the burglar since,” said Mrs. Cunningham, innocently.

She little dreamed what a discovery he had made, and he did not think it wise to enlighten her.

“He has not called upon me,” answered Paul, with justifiable evasion. “I don’t think I want to meet him again.”

“I hope he will never present himself here,” said the lady.

“He made me a promise that he would not,” said Paul.

“I suppose he wouldn’t mind breaking it.”

“No, but he may conclude that you would be on your guard.”

“There is something in that,” said Mrs. Cunningham, looking relieved. “My husband has telegraphed me that he will be here at eight o’clock, but I don’t want him to run the risk of encountering such a man.”

“Then you won’t need me to remain here?”

“No; but I wish you to stay till Mr. Cunningham returns. He will wish to see you.”

“Certainly, if you desire it,” said Paul, politely.

“My daughter will entertain you,” continued the lady. “Here she is.”

“Good evening, Paul!” said Jennie, cordially extending her hand, as she entered the room.

“Good evening!” responded Paul, brightening up.

“Would you like to play a game of dominoes?”

“I would be very glad to do so.”

“Then we’ll play ‘muggins.’ There’s more fun in that than in the regular game.”

So the two sat down and were soon deeply immersed in the game.

“Do you know, Paul,” said Jennie, suddenly, “I feel as if I had known you for a long time, though it is only about twenty four hours since we met.”

“I feel the same,” said Paul.

“I’m awfully glad they sent you here instead of some other telegraph boy.”

“Perhaps you would have liked another one better?”

“I don’t think I should, but I ought not to say so. It may make you vain.”

“Are boys ever vain? I thought it was only girls.”

“That’s a very impolite speech. I shall have to give you a bad mark!”

“Then I’ll take it all back!”

“You’d better,” said Jennie, with playful menace. “I hope you’ll come up some time when you are not sent for on business!”

“I would like to very much, if your mother is willing.”

“Why shouldn’t she be willing?”

“I am only a poor telegraph boy.”

“I don’t mind that. I don’t see why a telegraph boy isn’t as good as a boy in a store. My cousin Mark is in a store.”

It will be seen that these young people were rapidly coming to a very good understanding. Paul was not in love, but he certainly did consider Jennie Cunningham quite the nicest girl he had ever met.

So the time passed till Mr. Cunningham returned. His wife informed him briefly of what had occurred. They both entered the room together. He was a man of middle age, a very pleasant and easy mannered gentleman.

“Are you the boy who drove away the burglar?” he asked, with a smile.

“Yes, sir, I believe so,” answered Paul.

“Then let me add my thanks to those of my wife. You have done us a great service.”

“I am very glad to have had the chance,” said Paul.

“If you will come to my office tomorrow morning,” continued Mr. Cunningham, “I will thank you in a more effective way. Come at ten o’clock. As you may find it difficult to leave the office otherwise, tell the superintendent that I have an errand for you.”

“Very well, sir.”

“Here is my business card.”

Paid took the card and rose to go.

“Mamma,” said Jennie, “can’t you invite Paul to call and see us sometimes?”

“Certainly,” said the lady, smiling. “After what he has done he ought to have the freedom of the house. We shall be glad to see you as a visitor, Paul,” she said, kindly.

Paul left the house in a flutter of pleasant excitement. He was quite determined to avail himself of an invitation so agreeable.

He crossed over to Third Avenue, and returned by the elevated railway to the home of old Jerry.

In the evening Paul found old Jerry anxiously awaiting him.

“Have you found a new room, Paul?” he asked, eagerly.

“I haven’t had time,” Paul answered, “but I’ll go at once and see about it.”

“James will be here tomorrow,” said the old man, nervously, “and I—I am afraid of him. He is a bad man. He wants me to give him money. You know I have no money, Paul?” he concluded with a look of appeal.

Now Paul knew that old Jerry had money, and he could not truthfully answer as the old man desired him.

“You say so, and that is enough,” he said.

“But it’s true,” urged Jerry, who understood the doubt in Paul’s mind. “How could I get any money? What you give me is all we have to live on.”

“That isn’t much, at any rate.”

“No, Paul, it isn’t much. Couldn’t you give me half a dollar more? Two dollars and a half are very little for me to live on and pay the rent,” whined the old man.

The appeal would have moved Paul if he had not suspected that the old man had a considerable sum of money laid away. As it was, it only disgusted him and made him feel angry at Jerry’s attempt to deceive him.

“Are you sure you get no money except what I give you?” he asked, pointedly.

“What do you mean, Paul?” demanded the old man, looking alarmed. “What gave you the idea that I had any other money?”

“At any rate,” said the telegraph boy, “you haven’t any money to throw away on this son of yours. I have no doubt he’s a bad man, as you say.”

“He was always bad and troublesome, James was,” said old Jerry. “He was always wanting money from the time he was a boy.”

“When he was a boy there was some reason for his asking it, but now he is a man grown, isn’t he?”

“Yes, yes.”

“How old is he?”

“James must be nigh upon thirty,” answered Jerry, after a little reflection. “You won’t hire too expensive a room, Paul?” he added. “You know we are poor, very poor!”

“Not unless I am willing to pay the extra cost myself.”

“Don’t do that! Give me the extra money, Paul,” said Jerry, with eager cupidity. “I—I find it hard to get along with two dollars and a half a week.”

“You forget, Jerry,” said Paul, coldly, “that I must have my meals. I can’t live without eating.”

“You eat too much, Paul, I’ve long thought so. It’s hurtful to eat too much. It’s—it’s bad for the health.”

“I’ll take the risk,” said Paul, with a short laugh. “I am not afraid of dying of gout, Jerry, with my present bill of fare.”

“If you wouldn’t mind my going out a few hours every day, and asking kind gentlemen to help me, Paul, we—we could get along better.”

“I won’t hear of it, Jerry,” said Paul, sternly. “If I hear of your going out to beg I will leave you and[47] go off and live by myself. Then there will be no two dollars and a half coming to you every week.”

“No, no, don’t leave me, Paul,” said Jerry, thoroughly alarmed by this threat. “I won’t go out if you don’t want me to, though it’s very, very foolish to stay in, when there are so many kind gentlemen and ladies ready to give money to old Jerry.”

“Besides,” added Paul, “if you go out and stand in the street, your son will sooner or later find you out, and make trouble for you.”

“So he will, so he will,” chimed in the miser, with the old look of alarm on his face. “You are right, Paul, you are right. I must put it off. I—I wish he would go away somewhere—to—to California, or some place a great way off.”

Paul saw that he had produced the effect he intended upon the old man’s mind, and went out at once to look for a new room. He finally found one some half mile farther up town, in Ludlow Street—a little below Grand.

The room was better furnished than the one in which he and Jerry had lived for some years. There was a cheap carpet on the floor, a bed in one corner, and a shabby but comfortable lounge, on which Paul himself proposed to sleep. The rent was two dollars a month more than they had been accustomed to pay, but Paul concluded to say nothing of this to the old man, but quietly to pay it out of his own pocket. It would be but fifty cents a week, and he thought he could make that extra sum in some way. He was beginning to be more fastidious about his accommodations, now that he had seen how people lived uptown.

In fact, Paul was becoming ambitious. It was a very proper ambition, too. He had lived long enough in a squalid, miserable room, and now he meant to be better provided for.

“I am getting older,” he said to himself. “I ought to earn more money. I am sure I can somehow. I will keep my eyes open and see what I can find.”

Paul resolved to buy a bureau, if he could get one cheap, for at present he had absolutely no place in which to keep his small stock of clothing. He did not know exactly where the money was coming from, but he was hopeful, and had faith in himself. He was not waiting for something to turn up, as many lazy boys do, but he meant himself to turn up something.

Having concluded a bargain for the room, paying a dollar down, and promising to pay a further sum on Saturday night when he received his weekly pay, he returned to old Jerry.

“Well, Jerry,” he said cheerfully, “I’ve found a room.”

“Where is it, Paul?”

“In Ludlow Street.”

“Then let us go—at once. James might change his mind, and come round tonight. I don’t want to see him. He is a bold, bad man.”

Paul suggested that they had better not leave word with the neighbors where they were going, as this might furnish a clew to James Barclay, and put him on his father’s track.

Old Jerry eagerly assented to this, and the two started for their new home. They had very little to carry—at any rate, this was the case with the miser, and Paul’s wardrobe was not too extensive for him to carry it all with him at once.

When Jerry saw the room that Paul had engaged he was alarmed.

“This—this is too fine for us, Paul,” he said. “We can’t afford to pay for it. How much is the rent?”

“Six dollars a month,” answered Paul.

“We shall be ruined!” ejaculated Jerry, turning pale.

“It is two dollars more than we paid in the old place,” said Paul, “but it won’t come out of you. I will make a new arrangement with you—I will pay the entire rent, and give you a dollar and a half a week.”

“Make it two dollars, Paul,” said Jerry, in a coaxing tone.

“What are you thinking of? Do you want to starve me?” demanded Paul, sternly.

“I—I am so poor, Paul,” whined the miser.

“So am I,” answered Paul, “but I must keep enough to pay for my meals.”

Jerry saw that it would be useless to contest the point further, and settled himself in his new quarters, rather enjoying the improvement, but groaning inwardly over Paul’s extravagance. Paul threw himself on the lounge, after taking off his coat and vest, and, covering himself with a blanket, was soon sound asleep.

PAUL THREW HIMSELF ON THE LOUNGE, AND SOON WAS FAST ASLEEP.

Paul did not fail to meet the appointment at Mr. Cunningham’s office the next morning. He had no difficulty in getting away, for it was understood at the office that he was wanted to run an errand and his time would be paid for.

“You seem to be in with the Cunninghams, Number 91,” said the superintendent.

“Yes, sir, they are very kind to me,” answered Paul.

“That is well. We like to have boys on good terms with customers. It increases the business of the office.”

Mr. Cunningham was talking with another gentleman when Paul entered his office.

“Sit down, Paul,” he said in a friendly tone, indicating a chair. “I shall soon be at leisure, and then I will attend to you.”

“Thank you, sir,” said the telegraph boy.

He had to wait about ten minutes. Then Mr. Cunningham’s visitor left him, and he turned to Paul.

“How is business this morning?” he asked, with a smile.

“This is my first call, sir.”

“Oh, well, no doubt you will have plenty before the day is over.”

“Yes, sir, I am engaged for the afternoon.”

“Indeed! And in what way?”

“I am to go shopping with a lady.”

“Can’t she go by herself there?”

“Yes, sir, I suppose so, but she wants me to carry her bundles.”

“Retail merchants generally send them home.”

“Yes, sir, but she once had one miscarry, and now she prefers to take a boy with her.”

“How do you like that business?” asked Mr. Cunningham.

“It is rather tiresome,” answered Paul, “as the lady is hard to suit and spends a good deal of time in each store. However, there is one thing that reconciles me to it.”

“What is that?”

“She is liberal, and always gives me something for myself.”

“That is very considerate of her. I was speaking of that to my wife this morning.”

“Of what, sir?” inquired Paul.

“We both decided that you were entitled to a present for your brave defense of the house.”

Now I suppose it would have been the proper thing for Paul to protest against receiving any present, but I am obliged to record the fact that he had no objection to having his services acknowledged in that way.

“I only did my duty, sir,” he said, modestly.

“Very true, but that is no reason why I should not show my appreciation of the service rendered. I suppose you have no bank account?”

“I never got along as far as that, sir,” said Paul.

“Then I won’t give you a check, as it might inconvenience you.”

Paul was a little surprised, for a bank check sounded large, and the gratuities he usually received seldom reached as high as fifty cents.

Mr. Cunningham drew out his pocketbook, and, taking out three bills, placed them in Paul’s hands.

Paul’s eyes expanded when he saw that the first bill was a ten. But he was destined to be still more surprised, for each of the other two was a twenty. There was fifty dollars in all.

“Is all this for me?” he asked, almost incredulous.

“Yes, Paul.”

“But here are fifty dollars.”

“I am quite aware of it,” said the merchant, smiling. “That is the exact sum I intended to give you.”

“I don’t know how to thank you,” said Paul, warmly. “To me it is a fortune.”

“Excuse my giving you advice, but I hope you will spend it wisely.”

“I will try to do so, sir. I will put all but ten dollars in a savings bank.”

“You could not do better. You may in time be able to add to it.”

“I shall try to, sir, when I earn more money.”

“How much do you earn now?”

“With presents, it amounts to six or seven dollars a week—sometimes less.”

“You can’t save out of that?”

“No, sir; I live with an old man, and give him two dollars and a half a week for rent and other expenses. Hereafter I am to give him three dollars. I should give more, but I pay for my own meals.”

“Then you have no parents living?”

“No, sir; I am alone in the world.”

“Is the old man any relation to you?”

“No, sir.”

“When you need friends to call on you will always be welcome at my house.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Paul, gratefully, and he decided to avail himself of the invitation soon. He[53] was anxious to meet Jennie Cunningham again. Having no sister, he had enjoyed scarcely any opportunities of meeting girls, except such as sold matches or papers in the streets, and these, for the most part, were bold and unattractive.

Mr. Cunningham turned to his desk, and Paul saw that his interview was over.

He did not like to carry around so much money. He was liable to be robbed; that he could not afford. So he resolved to go around to the Bowery Savings Bank and deposit forty dollars, taking out a book. Then he would feel safe as to that. The ten dollars he had a use for, as he wished to buy a cheap bureau, or trunk; he had not quite made up his mind which.

He took the shortest cut to the Bowery Savings Bank. This is one of the largest and most important savings banks in the city, and its deposits exceed twenty millions. It is a blessing to thousands of salaried men and women, mechanics and others, in providing them a safe place of deposit for their surplus money.

Paul entered the bank, and, going up to the proper clerk, subscribed the books of the bank, giving his age, and other particulars necessary to identification; and then, rather to the surprise of the bank officer, wrote out a deposit check for forty dollars.

“You have just been paid off, I take it,” he said with a smile.

“Yes, sir,” answered Paul.

“Two weeks’ pay, I presume?”

“I earned it in considerably less time than that, sir.”

“Indeed!”

“Yes, I earned it all, and ten dollars besides, in one night.”

“Then your business is better than mine. I should be willing to exchange.”

“It isn’t a steady business,” said Paul.

“What is it?”

“Defending a house from burglars.”

“I am not quite sure how I should like that business; there might be some risk attending it.”

Paul’s business was completed, and he prepared to go away. The book he put in his pocket, and took his way back to the office on Broadway. He began to feel like a young capitalist. Forty dollars may not seem a very large sum to some of my fortunate readers, but Paul had never before possessed ten dollars at a time, and to him it seemed a small fortune.

He had no idea that his visit to the bank was observed by any one that knew him, but such was the case.

Old Jerry, as the reader already knows, was a depositor at the Bowery Savings Bank, and this very morning, having a small deposit to make, he was shambling along the Bowery, when he saw Paul descend the steps with a bank book in his hand. He was intensely surprised.

Old Jerry felt outraged at Paul’s withholding money from him for deposit in the savings bank.

“The—the thieving young rascal!” he muttered to himself, indignantly. “He is putting my money into the bank, and letting me starve at home, while he lives on the fat of the land, and lays up money. Me that have taken care of him ever since he was a little boy, and—and cared for him like a father.”

Jerry had a curious idea of the way fathers care for their children, judging from his words. When Paul was only six years old, he had been sent into the streets to sell matches and papers, and, being a bright, winning boy, had earned considerably more, even at that tender age, than many older boys.

At times Jerry had induced him to beg, but it was only for a short time. Paul had a natural pride and independence that made him shrink from asking alms, as soon as he was old enough to understand the humiliation of it. So there was never a time when he had not earned his own living, and more besides. But Jerry chose to forget this, and to charge Paul with ingratitude, when he discovered that he had a private fund of his own.

“I must get hold of that money,” thought Jerry. “I wonder how much Paul has got.”

There was no way of finding out, unless he got hold of the book, or inquired at the bank. He decided to do the latter. Accordingly he went over to[56] the bank, and entering it walked up to the receiving teller.

“Was there a boy named Paul Parton here just now?” he asked.

“Yes; what of it?”

“Did he put some money into the bank?”

“Yes.”

“How much was it?”

“We don’t give information about our depositors,” said the teller. “Is he your grandson?”

“Yes; that is, he lives with me.”

“You are a depositor also, are you not? I seem to remember your face.”

“Yes.”

“What is your name?”

“Jeremiah Barclay.”

“I remember now. Why do you want to know about this boy?”

“He ought to have given me the money, instead of putting it into the bank.”

“We have nothing to do with that. He did not steal it from you, I presume.”

“No,” answered Jerry, reluctantly. It occurred to him for an instant to claim that Paul had robbed him, but he was rather afraid that the telegraph boy would in that case become angry and leave him, and the sum he had in bank would not pay him for that.

The miser did not suspect that Paul had over five dollars laid up, having no knowledge of the handsome gift he had received from Mrs. Cunningham. But even if it were only five dollars, it was sufficient to excite Jerry’s cupidity, and he decided that he must manage to get possession of it.

“Then you won’t tell me how much money Paul has in the bank?”

“It is against our rules.”

Jerry felt that he was dismissed, and stumbled out[57] of the bank, forgetting, in his thoughts about Paul, the business of his own which had brought him there.

But there was other business for Jerry to attend to that morning. We are about to let the reader into a secret, which he had hitherto kept from Paul.

Not far away was a small tenement house which Jerry hired and sublet to tenants. Every month he called to collect his rents, and the difference between the rent he paid for the whole building, and the rents he collected from the tenants, gave him a handsome profit.

It was not rent day, but there were two of the tenants in arrears. One was a laborer, temporarily out of work, and the other was a poor widow who went out scrubbing, but was now taken down with rheumatism, and therefore not able to work.

The old man ascended with painful toil to the third floor, and called on the widow first.

She turned pale when she saw him enter, for she knew his errand, and how little chance there was of softening him.

“I hope you have got the rent for me this morning, Mrs. O’Connor,” said Jerry, harshly.

“And where would I get it, Mr. Barclay?” she asked. “It’s very little work I can do on account of the sharp pains I have.”

“That’s none of my business,” said Jerry, in a harsh tone. “You will have to go, then.”

“And would you put me on the street, me and my poor childer?” said the poor woman, with a troubled look. “I’m afraid it’s the hard heart you have, Mr. Barclay.”

“Don’t talk nonsense, Mrs. O’Connor,” said Jerry, sharply. “I can’t let you stay here for nothing. I—I’m very poor myself,” he added, with his customary whine.

“You poor!” repeated the widow, bitterly. “I’ve heard that you’re rolling in riches, Mr. Barclay.”

“Who—who says so?” asked Jerry, alarmed.

“Everybody says so.”

“Then you can tell ’em they’re very much mistaken.”

“What do you do with all the rent you get from this building, then?”

“I pay it away, that is, almost all of it. I don’t own the building. I—I hire it, and some months, on account of losses, I don’t make a cent,” asseverated Jerry. “I—I think I’m a little out take the year together.”

“Then why don’t you give it up if you don’t make any money out of it?”

“That—that is nothing to the purpose. Once more, Mrs. O’Connor, will you pay me my rent?”

“How can I when I have no money?”

“Then you must borrow it. I’ll give you till tomorrow, and not a day longer. Remember that, Mrs. O’Connor, will you not?”

Next Jerry visited the other tenant with rather better success, for he collected one dollar on account.

He waited eagerly for Paul to come home. He had made up his mind to explore Paul’s pockets after he was asleep and get possession of his bank book. With that, as he thought, he would go to the bank and draw the money that stood in Paul’s name. It would be a theft, but Jerry did not look at it in that light. He persuaded himself that he had a perfect right to take the property of the boy who was living under his guardianship, though, to speak properly, it was rather Paul that took care of him.

It was rather late in the evening when Paul got home, for every other evening he was employed. The old man was awake, but pretended to be asleep.[61] Paul took off his coat and vest, and threw himself on the lounge, covering himself up with a quilt. His clothes he put on a chair alongside.

It was not long before he was sound asleep, being much fatigued with the labors of the day.

Old Jerry got up cautiously from the bed. He, too, was dressed, for he seldom took the trouble to undress, and cautiously drew near the lounge. He took up Paul’s coat, and threw his claw-like fingers into an inside pocket. His eyes sparkled with delight as he drew out the telegraph boy’s bank book.

“I’ve got it!” he muttered, gleefully. “Paul isn’t any match for the old man! I—I wonder how much money he has saved up!”

Paul slept on, unaware of the cunning old man’s treachery, and of the danger to which his little treasure was exposed.

Old Jerry laid down Paul’s coat, and opened the bank book, of which he had just obtained possession. He was eager to ascertain how much Paul had saved up.

“Forty dollars!”

He could hardly believe his eyes.

How in the world could Paul have managed to save up forty dollars?

“Forty dollars!” exclaimed old Jerry, gleefully. “I’m in luck for once. Of course it belongs to me. I am Paul’s guardian, and have a right to his earnings. He shouldn’t have kept it from me. I—I will go to the bank and draw it all tomorrow. Then I will put it in in my own name. That will make it all right.” And old Jerry rubbed his hands joyfully.

After this theft, for it can be called by no other name, Jerry did not sleep much. He was too much excited by the unexpected magnitude of his discovery, and by his delight at adding so much to his own hoards. Then, again, he was afraid Paul might wake up, and, discovering his loss, demand from him the restitution of the book.

Generally Paul rose at six o’clock, as this enabled him to get his breakfast and get round to the telegraph company at seven. He generally waked about fifteen minutes before the hour, such was the force of habit.

This morning he woke at the usual time, but old[63] Jerry had got up softly and left the room twenty minutes before.

Turning over, Paul glanced toward the bed in the corner, and was surprised to see no signs of the old man.

“Jerry gone out already!” he said to himself, in amazement “I wonder what’s come over him. I hope he isn’t sick.”

Paul didn’t however borrow any trouble, for he concluded that Jerry had got tired of his bed, and gone out for a morning walk.

He lay till seven, and then, throwing off the quilt, rose from the lounge. He was already partly dressed, and only needed to put on his coat. Then, with a cheerful smile, he felt for his bank book, which he had placed in the inside pocket of his coat.

It was not there!

He started, and turned pale.

“Where is my bank book?” he asked himself in alarm.

Then it flashed upon him.

“Old Jerry has taken it!” he said, sternly, “and has slunk off with it before I am up. That’s why he got up so early. But I’ll put a spoke in his wheel. I’ll go to the bank and give notice that my book has been stolen. He shan’t draw the money on it, if I can prevent it.”