BOSWELLIANA.

From an original sketch by Langton.

BOSWELLIANA

THE COMMONPLACE BOOK

OF

JAMES BOSWELL

WITH A MEMOIR AND ANNOTATIONS

BY THE

Rev. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D.,

HISTORIOGRAPHER OF THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY

OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND, AND CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF

THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ENGLAND.

AND INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

BY THE

RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD HOUGHTON.

LONDON

PRINTED FOR THE GRAMPIAN CLUB

1874

MEMBERS OF THE GRAMPIAN CLUB.

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Patron.

His Grace the Duke of Argyll, K.T.

His Grace the Duke of Athole.

Right Hon. the Earl of Aberdeen.

Right Hon. the Earl of Airlie.

Sir Robert John Abercrombie, Bart., of Birkenbog.

General Sir John Aitchison, K.C.B., G.C.B.

The University of Aberdeen.

Robert Vans Agnew, Esq., of Sheuchan, M.P.

Lieut.-Colonel W. R. E. Alexander.

Lieut.-Colonel A. Stewart Allan.

John Addis, Esq.

Robert Barclay Allardice, Esq.

George Anderson, Esq.

John Anderson, Esq.

James Anderson, Esq., Q.C.

Peter Anderson, Esq.

Edward Adamson, Esq., M.D.

J. W. Adamson, Esq.

Francis Aberdein, Esq., of Keithock.

Walter Armstrong, Esq.

F. S. Arnott, Esq., C.B.

John Aiton, Esq.

Charles J. Alexander, Esq.

John Anderson, Esq., LL.D., C.E.

John Macaulay Arnaud, Esq.

The Most Hon. the Marquess of Bute.

Right Hon. Lord Borthwick.

Right Hon. Lord Burleigh.

Colonel Balfour of Balfour.

Arthur James Balfour, Esq.

John Balfour, Esq., of Balbirnie.

Robert Brown, Esq., of Underwood Park.

Sir Alexander Bannerman, Bart.

Lieut.-General Walter John Browne, C.B.

The Rev. G. R. Badenoch, LL.D., F.R.H.S.

Joseph Bain, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

Edward Chisholm Batten, Esq., M.A., F.R.S.E., of Aigas.

Richard Bennet, Esq.

Patrick Buchan, Esq., Ph.D.

John Buchanan, Esq., LL.D.

W. G. Beattie, Esq.

John Blackie, Esq.

Mark Boyd, Esq., of Merton Hall.

John Boyd, Esq., M.D.

Rev. George Weare Braikenridge, F.S.A. Scot.

Richard Rolt Brash, Esq. M.R.I.A.

A. J. Dennistoun Brown, Esq., of Balloch Castle.

Adam Brown, Esq.

John Brown, Esq.

James William Baillie, Esq., of Culter Allers.

Alexander Beattie, Esq., J.P.

[vi]Colin Rae Brown, Esq.

Walter Berry, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

William Blewitt, Esq.

John Buchanan, Esq.

James Brunlees, Esq.

William Cunliffe Brooks, Esq., M.P.

Right Hon. the Earl of Camperdown.

Right Hon. the Earl of Cawdor.

Right Hon. Lord Clinton.

Thomas Leslie Melville Cartwright, Esq.

Major Pemberton Campbell.

Captain Campbell.

James Campbell, Esq.

Rev. Francis Cameron, D.D.

Charles Clark, Esq.

J. Ross Coulthart, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

George Cruikshank, Esq., Honorary.

Skene Craig, Esq.

Benjamin Bond Cabbell, Esq., F.R.G.S.

Benjamin Bond Cabbell, Esq., jun.

Thomas Constable, Esq.

R. H. Campbell, Esq.

R. Campbell, Esq.

Lieut.-Colonel D. Campbell.

F. R. Campbell, Esq.

David A. Carnegie, Esq.

Colonel Charles Cheape.

William Cook, Esq.

A. Angus Croll, Esq.

J. A. Chalmers, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

F. de Chaumont, Esq.

Captain A. M’Ra Chisholm.

George Christie, Esq.

Jonathan Henry Christie, Esq.

James Crichton, Esq., Kilbryde Castle.

Frederick William Cosens, Esq.

Thomas Craig Christie, Esq., of Bedley.

George T. Clark, Esq., of Dowlais.

T. Moir Clark, Esq.

John Coutts, Esq.

George R. Cox, Esq.

Colonel John H. Corsar.

Captain George Frederick Russell Colt.

The Chisholm.

Chetham Library, Manchester.

Charles Chalmers, Esq.

Anderson Cooper, Esq.

Right Hon. the Earl of Dalhousie, K.T.

Right Hon. the Earl of Dunmore.

Duncan Davidson, Esq., of Tulloch.

George Stirling Home Drummond, Esq., of Blair Drummond.

General John Drummond, F.R.G.S.

Alexander Duncan, Esq.

W. A. Duncan, Esq.

James W. Davidson, Esq.

John Arthur Dalziel, Esq.

A. G. Dallas, Esq., of Dunain.

Peter Denny, Esq.

Edward Octavius Douglas, Esq., of Killichassie.

James Davidson, Esq., of Ruchell.

Hector Drysdale, Esq.

George H. Dickson, Esq.

William Dickson, Esq., J.P., F.S.A., F.S.A. Scot.

A. H. Dennistoun, Esq.

Right Hon. the Earl of Elgin.

Right Hon. the Lord Elibank.

William Euing, Esq., F.R.S.E., F.S.A. Scot.

Andrew Edgar, Esq., LL.D.

The University of Edinburgh.

John Elphinstone, Esq.

Miss Mary Caroline Edgar.

Logan B. Edgar, Esq.

William Erskine, Esq.

John Alexander Ewen, Esq.

James D. Edgar, Esq., M.P., Canada.

Jonathan Edgar, Esq.

Right Hon. the Earl of Fife.

Sir William G. N. T. Fairfax, Bart.

Robert Francis Fairlie, Esq.

A. Falconer, Esq.

Thomas Falconer, Esq.

James R. Ferguson, Esq.

Sir William Forbes, Bart., of Craigievar.

Peter Forbes, Esq.

David Forsyth, Esq.

J. W. Fleming, Esq., F.R.C.S.

[vii]Robert Ferguson, Esq.

Robert O. Farquharson, Esq., F.S.A., of Haughton.

Francis Garden Fraser, Esq., of Findrack.

F. Mackenzie Fraser, Esq.

William Fraser, Esq., Edinburgh.

John Fowler, Esq., of Braemore.

William Nathaniel Fraser, Esq., of Tornaveen.

James Fletcher, Esq.

William Fraser, Esq., London.

Peter S. Fraser, Esq.

Right Hon. the Earl of Glasgow.

Lieut.-General Sir J. Hope Grant, G.C.B.

University of Glasgow.

William Galbraith, Esq.

Thomas L. Galbraith, Esq.

H. J. Galbraith, Esq.

J. Graham Girvan, Esq.

Lieut.-Colonel G. Gardyne.

Samuel Gordon, Esq.

J. Chisholm Gooden, Esq.

Peter Graham, Esq.

James Graham, Esq.

W. Cosmo Gordon, Esq., of Fyvie.

Alexander Gordon, Esq.

George J. R. Gordon, Esq., yr., of Ellon.

John Gordon, Esq.

James Guthrie, Esq.

Captain Alexander Graeme, R.N.

E. W. Garland, Esq.

Arbuthnot C. Guthrie, Esq., of Duart.

Colonel C. J. Guthrie, of Scots Calder.

C. Seaton James Guthrie, Esq., Jun., of Scots Calder.

John Gray, Esq., Q.C.

Thomas Gray, Esq.

The Most Hon. the Marquis of Huntly.

The Right Hon. the Earl of Hopetoun.

The Right Hon. the Earl of Home.

Right Hon. Lord Herries.

Right Hon. Lord Houghton, F.S.A.

Rev. J. O. Haldane.

Peter Hall, Esq.

Archibald Hume, Esq.

Robert Hay, Esq., of Nunraw.

James Henderson, Esq.

Archibald Hamilton, Esq., of South Barrow.

H. W. Hope, Esq., of Luffness.

Major John Fergusson Home, of Bassendean.

William Crichton Hepburn, Esq.

Alexander Howe, Esq., W.S.

Charles Edward Hamilton, Esq.

Henry Huggins, Esq.

William H. Hill, Esq.

Charles A. Howall, Esq.

John Hannan, Esq.

The Rev. J. Brodie Innes, of Milton Brodie.

Richard Johnson, Esq.

James Auldjo Jamieson, Esq., W.S.

Andrew Jamieson, Esq.

Colonel W. Ross King, of Tertowie, F.R.G.S., F.S.A. Scot.

Rev. William A. Keith, M.A.

Thomas Kennedy, Esq.

George R. Kinloch, Esq.

John Roger Kinninmont, Esq.

George Middleton Kiell, Esq.

Frederick Baker Kirby, Esq.

The Right Hon. the Earl of Lauderdale.

Alexander Laing, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

J. W. Larking, Esq.

James Forbes Leith, Esq., of Whitehaugh.

John Lambert, Esq.

Rev. James Legge, D.D., LL.D.

William Leask, Esq.

J. Lenox, Esq.

James Lawrie, Esq.

Alexander Leslie, Esq.

James W. Laidlay, Esq., F.R.S.E., F.R.S. Scot.

[viii]James Lawrence, Esq.

David Laing, Esq., LL.D., F.S.A. Scot., Honorary.

William Lidderdale, Esq.

Hugh G. Lumsden, Esq., of Clova.

Right Hon. the Earl of Mar.

Right Hon. the Earl of Minto.

Right Hon. the Earl of Moray.

Keith Stewart Mackenzie, Esq., of Seaforth.

William Alexander Mackinnon, Esq., C.B.

P. Mackinnon, Esq.

The Mackintosh.

Donald MacIntyre, Esq.

Alexander Mackintosh, Esq.

Angus Mackintosh, Esq., of Holme.

Captain Colin Mackenzie.

William Menelaus, Esq.

William MacCash, Esq.

A. M’Culloch, Esq.

Charles Fraser Mackintosh, Esq., of Drummond, M.P.

Donald MacInnes, Esq.

Alexander MacInnes, Esq.

Hugh A. Mackay, Esq.

R. B. E. Macleod, Esq., of Cadboll.

T. Comyn Macgregor, Esq., of Brediland.

Hugh Edmonstoune Montgomerie, Esq., F.S.A.

John D. Macdonald, Esq., M.D., F.R.S.

J. S. Muschet, Esq., M.D., of Birkhill.

Sir James Ranald Martin, C.B., F.R.S.

W. H. Macfarlane, Esq.

George Macfarlane, Esq.

F. W. Malcolm, Esq.

John Malcolm, Esq.

I. McBurney, LL.D., F.S.A. Scot., F.E.I.S.

William Thomas Morrison, Esq.

John Whitefoord Mackenzie, W.S.

Colonel Macdonald Macdonald, of St. Martins.

Sir Robert Menzies, Bart., of Castle Menzies.

Sir Kenneth Mackenzie, Bart.

Robert W. Mylne, Esq., F.R.S., F.G.S., F.S.A. Scot.

Rev W. O. Macfarlane, M.A. Oxon.

Sir William Maxwell, Bart., of Monreith.

F. Maxwell, Esq., of Gribton.

J. Milne, Esq.

James Cornwall Miller, Esq.

Captain C. Munro, of Foulis.

Alexander B. M’Gregor, Esq.

L. Mackinnon, Esq.

John M’Rae, Esq.

David W. Murray, Esq.

James D. Marwick, Esq.

John M’Ewan, Esq.

David P. M’Euen, Esq.

Peter Handyside M’Kerlie, Esq.

Robert Mure M’Kerrell, Esq.

D. Macneil, Esq.

J. B. Murdoch, Esq.

J. W. M’Cardie, Esq., of Newpark, F.R.H.S.

James Maclaren, Esq.

William M’Combie, Esq., of Easterskene.

John C. M’Naughton, Esq., of Kilellan.

George M’Corquodale, Esq.

Colin James Mackenzie, Esq.

Graeme R. Mercer, Esq., of Gorthy.

Right Hon. Lord Napier and Ettrick.

The Hon. Lord Neaves.

W. J. Newman, Esq.

James Neish, Esq., of Laws.

Hugh Neilson, Esq.

Donald Ogilvie, Esq., of Clova.

Thomas L. Kington Oliphant, Esq., of Gask, F.S.A.

Sir J. P. Orde, Bart., of Kilmory.

Dr. William O’Donnovan.

James G. Orchar, Esq.

Colonel J. Oliphant.

R. W. Cochran Patrick, Esq., of Ladyland.

Sir J. Noël Paton, R.A.

James Park, Esq.

Hugh Penfold, Esq.

Cornelius Paine, Esq.

[ix]W. S. Purves, Esq.

Alexander Pringle, Esq., of Yair.

His Grace the Duke of Richmond.

Right Hon. the Earl of Rosebery.

Right Hon. the Earl of Rosslyn.

John Rae, Esq., LL.D., F.S.A.

Lieut.-Colonel John Ramsay, of Barra.

William Rider, Esq.

Patrick Rankin, Esq., jun.

Rev. Charles Rogers, LL.D., F.R.H.S., F.S.A. Scot., Secretary, Grampian Lodge, Forest Hill, S.E.

E. William Robertson, Esq., of Chilcote.

Edward J. Reed, Esq., C.B., M.P.

James Robb, Esq.

Andrew Ramsay, Esq., LL.D., F.R.S.

Rev. David Ogilvy Ramsay.

Major Rose, of Kilravock.

George W. H. Ross, Esq.

James Ross, Esq.

Robert Hamilton Ramsay, Esq., M.D.

The Hon. Edward S. Russell.

George Russell, Esq.

William Reid, Esq., W.S., F.S.A. Scot.

R. Milne Redhead, Esq., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.

Right Hon. the Earl of Seafield.

Right Hon. the Earl of Strathmore.

Right Hon. the Earl of Stair.

Right Hon. Lord Saltoun.

Right Hon. Sir John Stuart, F.S.A. Scot.

The Hon. Sir Charles Farquhar Shand.

George Edwin Swithinbank, LL.D., F.S.A. Scot.

William H. Smith, Esq.

Alexander Smith, Esq.

Captain Robert Steuart, of Westwood.

David Semple, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

Thomas Stratton, Esq., M.D.

Charles A. Stewart, Esq., of Achnacone.

James Stillie, Esq.

T. W. Swinburne, Esq.

Alexander B. Stewart, Esq.

Thomas Sopwith, Esq., F.R.S., F.R.H.S.

Charles Stewart, Esq., R.N., F.S.A. Scot.

A. Campbell Swinton, Esq., F.S.A. Scot., of Kimmerghame.

Charles Shaw, Esq.

Sion College, London.

Robert R. Stodart, Esq.

C. J. Stewart, Esq.

George Stewart, Esq.

William Stewart, Esq.

H. King Spark, Esq.

John Shand, Esq., W.S.

James Frederick Spurr, Esq.

The Right Hon. Lord Talbot de Malahide.

Sir Walter Calverly Trevelyan, Bart., F.S.A., F.G.S., F.S.A. Scot.

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple.

Alexander Tod, Esq., F.S.A. Scot.

Charles Tennant, Esq.

Gilbert Rainey Tennent, Esq.

Robert Tennant, Esq.

W. J. Taylor, Esq., of Glenbarry.

Thomas Aubrey Turner, Esq.

John Turnbull, Esq.

John Tweed, Esq.

Andrew Usher, Esq.

Right Hon. Lord Wharncliffe.

Sir Albert William Woods, F.S.A.

Rev. John G. Wright, LL.D.

George Ferguson Wilson, Esq., F.R.S.

William Thorburn Wilson, F.S.A. Scot.

Archibald Weir, Esq., M.D.

Thomas A. Wise, Esq., M.D., F.S.A. Scot., F.R.H.S.

J. P. Wise, Esq., Rostellan Castle.

Miss Catherine Mary Watson.

Fountaine Walker, Esq., of Foyers.

J. A. Woods, Esq.

James Wingate, Esq.

[x]Edward Wilson, Esq.

Charles H. H. Wilson, Esq., of Dalnair.

Mrs. W. Wilson.

Andrew Wark, Esq.

Rev. W. H. Wylie.

Allan A. Maconochie Welwood, Esq., of Meadowbank.

T. W. Spencer Waugh, Esq.

Randolph Gordon Erskine Wemyss, Esq., of Wemyss and Torrie.

Mrs. Wilkie.

Evan C. Sutherland Walker, Esq., of Skibo.

PREFACE.

James Boswell had not, by publishing his great work, the Life of Dr. Samuel Johnson, completed his literary plans. He preserved the letters he received from notable persons, and retained copies of his own. For many years he kept a journal, in which he recorded not merely his conversations with Dr. Johnson, but the diurnal occurrences of his own life. Respecting his journal, in a letter to his friend Mr. Temple, dated 22nd May, 1789, he writes:—“You have often told me that I was the most thinking man you ever knew; it is certainly so as to my own life. I am continually conscious, continually looking back or looking forward, and wondering how I shall feel in situations which I anticipate in fancy. My journal will afford materials for a very curious narrative. I assure you I do not now live with a view to have surprising incidents, though I own I am desirous that my life should tell.” Boswell evidently intended to adapt the contents of his journal to an autobiography; his early death precluded the intention.

Besides a journal, Boswell kept in a portfolio a[xii] quantity of loose quarto sheets, inscribed on each page Boswelliana. In certain of these sheets the pages are denoted by numerals in the ordinary fashion; another portion is numbered by the folios; while a further portion consists of loose leaves and letterbacks. The greater part of the entries are made so carefully as to justify the belief that the author intended to embody the whole in a volume of literary anecdotes.

At Boswell’s death his portfolio was sold along with the books contained in his house in London. It came into the possession of John Hugh Smyth Pigott, Esq., of Brockley Hall, Somersetshire, an indefatigable book collector. On Mr. Pigott’s death in 1861 the volume, bound in russia, was sold along with the stores of the Brockley library. Purchased by Mr. Thomas Kerslake, bookseller in Bristol, it was afterwards sold by him to Lord Houghton. By his lordship it was lately handed to the Grampian Club, with a view to publication.

Boswell’s commonplace-book exhibits some of the author’s weaknesses, but is on the whole a valuable repertory. The social talk of leading persons during the latter part of the century is graphically depicted. Considerable light is thrown on the character of individuals respecting whom every fragment of authentic information is treasured with interest. In preparing the commonplace-book for the press the Editor has omitted a few entries which transgressed on decorum. He has generally retained the author’s orthography.

The Memoir has been prepared with a desire to depict the author’s history in his own words. Letters to correspondents have been copiously introduced. Of these a most interesting portion have been obtained from the volume of Boswell’s Letters to Mr. Temple, published by Mr. Bentley, under the care of Mr. Francis. It is curious to remark that these letters, like the commonplace-book, left the family of the owner, and were accidentally discovered in the shop of a trader at Boulogne.

The Editor cannot venture to enumerate all the kind friends who have aided his inquiries. He has been indebted to Lord Houghton for important particulars. The representatives of Thomas David Boswell, the biographer’s brother, and of his uncle, Dr. John Boswell, have been most polite and obliging in their communications. The Rev. W. H. Wylie has kindly furnished Boswell’s address to the Ayrshire constituency.

Grampian Lodge,

Forest Hill, Surrey,

May, 1874.

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

By Lord Houghton.

There is no word of vindication or appreciation to be added to Mr. Carlyle’s estimate of the character and merits of James Boswell. That judgment places him so high that the most fantastic dream of his own self-importance would have been fully realized, and yet there is no disguise of his follies or condonation of his vices. We understand at once the justice and the injustice of his contemporaries, and while we are amused at the thought of their astonishment could the future fame of the object of so much banter and rude criticism have been revealed to them, we doubt whether, had we been in their place, our misapprehension and depreciation would not have been still greater than theirs.

It was the object of Boswell’s life to connect his own name with that of Dr. Johnson; the one is now identified with the other. He aspired to transmit to future time the more transitory and evanescent[xvi] forms of Johnson’s genius; he has become the repository of all that is most significant and permanent. The great “Dictionary” is superseded by wider and more accurate linguistic knowledge; the succinct and sententious biographies are replaced, where their subjects are sufficiently important, by closer criticisms and by antiquarian details, while in the majority of his subjects the Lives and Works of the writers are alike forgotten. The “Rambler” and the “Idler” stand among the British Essayists, dust-worn and silent; and though a well-informed Englishman would recognise a quotation from “Rasselas” or “London,” he would hardly be expected to remember the context.[1] But the “Johnsoniad” keeps fresh among us the noble image of the moralist and the man, and when a philosopher of our time says pleasantly of Boswell what Heinrich Heine[xvii] said gravely of Goethe, that he measures the literary faculty of his friends by the extent of their appreciation of his idol, it is to a composite creation of the genius of the master and of the sympathetic talent of the disciple that is paid this singular homage. For it was assuredly a certain analogy of character that fitted Boswell to be the friendly devotee and intellectual servitor of Dr. Johnson, and the resemblances of style and manner which are visible even in the fragments brought together in this volume cannot be regarded as parodies or conscious imitations, but rather as illustrations of the mental harmony which enabled the reporter to produce with such signal fidelity, in the words of another, his own ideal of all that was good and great.

“Elia,” with his charming othersidedness, writes, in one place, “I love to lose myself in other men’s minds,” and in another, “the habit of too constant intercourse with spirits above you instead of raising you, keeps you down; too frequent doses of original thinking from others restrains what lesser portion of that faculty you may possess in your own. You get entangled in another man’s mind, even as you lose yourself in another man’s ground; you are walking with a tall varlet, whose strides outpace yours to lassitude.” Both observations are true, and instances are not wanting of the spirit of reverence and the habit of waiting on the words and thoughts of those who are regarded as the spokesmen of authority, emasculating the self-reliance and[xviii] thralling the free action of superior men. This is especially observable in political life, where a certain surrender of independence is indispensable to success, but where, if carried too far, it tends to dwarf the stature and plane down the beneficial varieties of public characters. But there will always be many forces that militate against this courtliness in the Republic of Letters; leading men will have their clique, and too often like to be kings of their company, but more damage is done to themselves than to those who serve them, and there is little fear of too rapid a succession of Boswells or Eckermanns.

In these days of ready and abundant writing the value of Conversation, as the oral tradition of social intercourse, is not what it was in times when speech was almost the exclusive communicator of intelligence between man and man. Yet there will ever be an appreciation of the peculiar talent which reproduces with vivacity those fabrics of the hour, and gives to the passing lights and shades of thought an artistic and picturesque coherence. This is the product of a genial spirit itself delighting in the verbal fray, and of a society at once familiar and intellectual. We have from other sources abundant details of the vivacity of the upper classes of the Scottish community in the latter half of the last century and the beginning of the present. It had the gaiety which is the due relaxation of stern and solid temperaments, and the humour which is the genuine reverse of a deep sense of realities and an inflexible logic. It was intemperate, not with the intemperance of other northern nations, to whom intoxication is either a diversion to the torpor of the senses, or a narcotic applied by a benevolent nature to an anxious and painful existence, but with a conviviality which physical soundness and moral determination enabled them to reconcile with the sharpest attention to their material interests and with the hardest professional work.

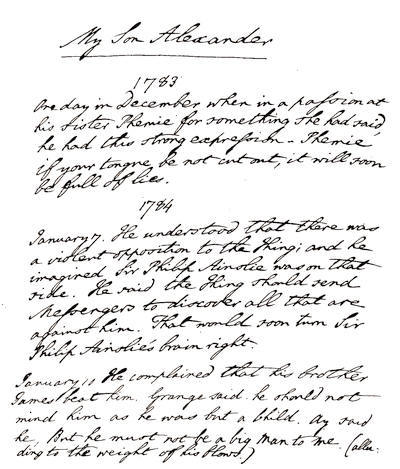

FAC-SIMILE OF A PAGE OF BOSWELL’S COMMONPLACE BOOK

IN THE POSSESSION OF LORD HOUGHTON.

Scotland had had the remarkable destiny in its earlier history of assimilating to itself the elements of a finer civilisation without losing its independence or national character; and it had even interchanged with the continent of Europe various influences of manners and speech. It had thus retained a certain intellectual self-sufficiency, especially in its relations with English society and literature, which never showed itself more distinctly than in its estimate of Dr. Johnson and of his connection with Boswell. In the pamphlets, and verses, and pictures of the time, Boswell appears as a monomaniac, and Johnson as an impostor. The oblong quarto of Caricatures which followed their journey to the Hebrides shows that Boswell not only did not gain any favour from his countrymen, by introducing among them the writer, who, however little understood in his entire worth, nevertheless held a high place among English wits and men of letters, but brought abundant ridicule on himself,[xx] his family, and his friend. It required all Boswell’s invincible good humour to withstand the sarcasm that assailed him. Dr. Johnson certainly repaid with interest the prejudice and ill-will he encountered, but it remains surprising that so good and intelligent a company did not better recognise so great a man. We did not so receive Burns and Walter Scott. The agreeable reminiscences of Lord Cockburn and Dean Ramsay have given us the evening lights of the long day of social brightness which Scotland, and especially Edinburgh, enjoyed; and if this pleasantness is now a thing of the past, the citizens of the modern Athens have only shared the lot of other sections of mankind, even of France, par excellence, the country of Conversation.[2]

This decadence in the art and practice of the communication of ideas, and in the cultivation of facile and coloured language, is commonly attributed to the wide extension of literature and the press, which give to every man all the knowledge of matters of interest which he can require without the intervention of a fellow-creature. It may be that men may now read and think too much to talk, but the change is, perhaps, rather the effect of certain alterations in the structure of society itself, accompanied by the fastidiousness that tries to make up by silence and seclusion for the arbitrary distinctions and recognised barriers, which limited and defined the game of life, but admitted so much pleasant freedom within the rules. We can however, still acknowledge the value of such records as those of the late Mr. Nassau, Senior, whose “Conversations” with the most eminent politicians and men of action of his time, especially in France, afford trustworthy and interesting materials for the future historian, and where a legal mind and well-trained observation take the place of vivid representation and literary skill. “Quand un bon mot,” writes Monsieur L.’Enfant in one of his prefaces to his “Poggiana” “est[xxii] en même temps un trait d’Histoire, on fait aisèment grace à’ce qui peut lui manquer du côté de la force et du sel.”

The title of “Boswelliana,” which the editor has taken from the original manuscript, is hardly correct. This is, in fact, one of the note-books of the anecdotes and facetiæ of the society in which Boswell lived; and though such a use of the termination may find some analogy in the Luculliana,—cherries that Lucullus brought from Pontus—and the Appiana—apples introduced into Rome by him of the Appian way,—yet the term “Ana,” in its most important applications, has always referred not to the collector, but to the personage or at any rate to the subject-matter of the book. Some vindication for its use on the present occasion may, however, be found in those instances in which Boswell acts as Bozzy to himself, and where the opinions and the mode of enunciating them are so thoroughly Boswellian that they give a characteristic flavour to the whole. What can be more delightfully his own than the prefixes “Uxoriana,” and “My son Alexander?”

There is some mystery in the insertion of certain occasional Johnsoniana, which could hardly have found their way into this collection, if Boswell had at the time been keeping special memoranda of his great Oracle. They are not very numerous nor consecutive, nor do they imply that at the time they were taken down they were intended as portions of the magnum opus. Most[xxiii] of them, however, are incorporated in it, and are only repeated here to preserve the integrity of the manuscript. The few omissions, such as they are, are of the same character as the lacunæ in the Temple letters.

The historical and biographical annotation of these anecdotes has been a work requiring considerable local knowledge and antiquarian research. Executed, as it is, by Dr. Rogers, it affords an interesting social picture of the Scotland of the day, and there are many families still living, who will here gladly recognise and welcome the words and thoughts of their ancestors.

MEMOIR

OF

JAMES BOSWELL.

As Dr. Johnson’s biographer, and the chronicler of his conversations, James Boswell is entitled to remembrance. On the publication of his “Life of Johnson,”—though seven years had elapsed since the moralist’s decease, and two memoirs had in the interval appeared,—a deep interest was excited; and the author, whose peculiarities had hitherto subjected him to ridicule, at once attained a first place as a biographer. Time, which effects many changes in literary popularity, has borne in an even current the “Life of Johnson,” and therewith in every home of lettered Britons has rendered familiar the name of Boswell.

Representing a landed branch of a Norman House, James Boswell inherited no small share of family pride, a point of character which under proper regulation might have proved salutary. Sieur de Bosville accompanied William of Normandy into England, and held a considerable command at the battle of Hastings. His descendants migrated into Scotland during the reign of David I., and there acquired lands in the county of Berwick. Robert Bosville obtained the lands of Oxmuir, in Berwickshire, under[2] William the Lion; he witnessed many charters in the reign of that monarch. He was father of Adam de Bosville de Oxmuir, whose name appears in an obligation of Philip de Lochore in 1235, during the reign of Alexander II. In the lands of Oxmuir he was succeeded by his son Roger, and his grandson William de Bosville, the latter of whom was compelled with other barons to swear fealty to Edward I. in 1296. Richard, son of William, obtained from King Robert the Bruce, lands near Ardrossan, in Ayrshire, in addition to his estates in Berwickshire.

Roger de Boswell, second son of Richard of Oxmuir, married in the reign of David II., Mariota, daughter and co-heiress of Sir William Lochore of that ilk, with whom he obtained half the barony of Auchterderran, in Fife. In this barony he was succeeded by his son John de Boswell, who espoused Margaret, daughter of Sir Robert Melville, of Carnbee. Their son, Sir William Boswell, was judge in a perambulation of the lands of Kirkness and Lochore. He married Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of Alexander Gordon, with whom he got some lands in the constabulary of Kinghorn. His son, Sir John Boswell, designed of Balgregie, married, early in the fifteenth century, Mariota, daughter of Sir John Glen, and with her obtained the barony of Balmuto, in Fife.

Sir John Boswell, of Balmuto, was succeeded by his son David, who married first Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Melville, of Raith, and secondly, Isabel, daughter of Sir Thomas Wemyss, of Rires, relict of David Hay, of Naughton. Robert, younger son by the first marriage, became parson of Auchterderran, and was much esteemed for his piety and learning: he attained his hundredth year. David, the elder son, obtained, in 1458, from James II., by a charter under the great seal, the lands of Glasmont, in Fife. He married first Grizel, daughter of[3] Sir John Wemyss of that ilk; and secondly, in 1430, Lady Margaret Sinclair, daughter of William, Earl of Orkney and Caithness. Thomas, eldest son of the second marriage, obtained from James IV., as a signal mark of royal favour, the estate of Auchinleck,[3] in Ayrshire. He was slain at Flodden on the 9th September, 1513. By his wife Annabella, daughter of Sir Hugh Campbell, of Loudoun, he had an only son David, who, succeeding to the paternal estate, espoused Lady Janet Hamilton, daughter of James, first Earl of Arran. David was succeeded by his son John, whose first wife was Christian, daughter of Sir Robert Dalzell, of Glenae, progenitor of the Earls of Carnwath. Of this marriage, James, the eldest son, succeeded to Auchinleck. He died in 1618, leaving by his wife, Marion Crawford, of Kerse, six sons, three of whom entered the service of Gustavus Adolphus, and ultimately settled in Sweden. David Boswell, the eldest, succeeded to Auchinleck; he was an ardent supporter of Charles I., and was fined ten thousand marks for refusing to subscribe the Covenant. He married Isabel, daughter of Sir[4] John Wallace, of Cairnhill, but having no male issue, he was at his death in 1661 succeeded by his nephew David, son of his next brother James by his wife, a daughter of Sir James Cunninghame, of Glengarnock.

David Boswell of Auchinleck espoused Anne, daughter of James Hamilton of Dalziel, by whom, besides three daughters, he had two sons, James and Robert. The latter settled in Edinburgh as a Writer to the Signet, and acquiring a handsome fortune, purchased from his kinsman, Andrew Boswell, the estate of Balmuto, which had belonged to his ancestors. His son, Claude James Boswell, born in 1742, passed advocate in 1766, and after serving eighteen years as sheriff of Fife, was in 1798 raised to the bench, under the judicial title of Lord Balmuto.[4] His lordship died on the 22nd July, 1824.

James Boswell, elder son of David Boswell of Auchinleck, succeeded to the paternal estate: he practised as an advocate, and attained considerable eminence in his profession. By his wife, Lady Elizabeth Bruce, daughter of Alexander, second Earl of Kincardine, he had two sons and a daughter, Veronica; she married David Montgomerie, of Lainshaw, and his daughter Margaret espoused James Boswell, the subject of this memoir. John, younger son of James Boswell of Auchinleck, studied medicine, and became censor of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh. Alexander, the elder son, succeeded to Auchinleck on his father’s death in 1748.

Through his father, Alexander Boswell was attracted to[5] legal studies; he passed advocate 29th December, 1729, and after a period of successful practice at the bar, was in 1743 appointed sheriff of Wigtonshire. He was raised to the bench in 1754, when he assumed the title of Lord Auchinleck;[5] he was appointed a Lord of Justiciary in the following year.

About the year 1739, Alexander Boswell married his cousin[6] Euphemia Erskine, descended of the ennobled House of Erskine of Mar. Her father, Colonel John Erskine, was a younger son of the Hon. Sir Charles Erskine, first baronet of Alva, and her mother was Euphemia, one of the four daughters of William Cochrane of Ochiltree, a scion of the noble House of Dundonald by his wife Lady Mary Bruce, eldest daughter of Alexander, second Earl of Kincardine. Of the marriage of Alexander Boswell and Euphemia Erskine were born three sons: John, the second son, became a military officer and died unmarried; David, the youngest, entered a house of business, and at the close of his apprenticeship in 1768 joined partnership with Charles Herries, a Scotsman, and Honorius Dalliol, a Frenchman, in establishing a mercantile house at Valencia in Spain. On account of the Spaniards being prejudiced against the name of David, as of Jewish origin, he assumed the Christian name of Thomas. On account of the war he left Spain in 1780, when he settled in London, and commenced business as a merchant and banker. He afterwards accepted a[6] post in the Navy Office, where he became the head of the Prize Department. He purchased the estate of Crawley Grange, Buckinghamshire, and died in 1826. A man of grave deportment and correct morals, he was esteemed for his discretion, urbanity, and intelligence. By his marriage with Anne Catherine, sister of General Sir Charles Green, Bart., he became father of one child, Thomas David, who was born 24th September, 1800. This gentleman succeeded his father in the estate of Crawley Grange; he married in 1841 Jane, daughter of John Barker, Esq. Having died without issue, his estate passed to another branch of the Boswell family.

James Boswell, eldest son of Lord Auchinleck, was born at Edinburgh on the 29th October, 1740. He received his rudimentary training from a private tutor, Mr. John Dun, a native of Eskdale, and who, on the presentation of his father, was, in 1752, ordained minister of Auchinleck. He was afterwards sent to a school at Edinburgh, taught by Mr. James Mundell, a teacher of eminence. Afterwards he was enrolled as a pupil in the High School, under Mr. John Gilchrist, one of the masters, a celebrated classical scholar.[7]

Possessed of strong religious and political convictions, Lord Auchinleck sought to imbue his children with a love of Presbyterianism and a loyal attachment to the House of Hanover. In those aims he was assisted by his wife, a woman of vigorous sagacity and most exemplary piety. To her affectionate counsel rather than to the wishes of his father, the eldest son was disposed to yield some reverence. But he early affected to despise the simple ritual of the Presbyterian Church, and in direct antagonism to his father’s commands he declared himself a Jacobite and a warm adherent of the exiled House. He[7] related to Dr. Johnson, that when his father prayed for King George, he proceeded to pray for King James, till one day his uncle, General Cochrane, gave him a shilling on condition that he would pray for the Hanoverian monarch. The bribe overcame his scruples, and he did as he was asked.

With a view to his becoming an advocate at the Scottish Bar, Boswell entered the University of Edinburgh. There he formed the acquaintance of Mr. William Johnson Temple, from Allardine in Northumberland, a young gentleman preparing in the literary classes for orders in the English Church. Mr. Temple was Boswell’s senior, and much surpassed him in general knowledge. He belonged to an old and respectable, if not an affluent family, and he was of a pleasing and gentlemanly deportment. The exiled king being forsaken, he became Boswell’s next hero. In parting from him at the close of their first college session, Boswell begged that their friendship might be maintained by correspondence; and letters actually passed between them for thirty-seven years. To Boswell’s share of that correspondence we are indebted for many materials illustrative of his life.

It will be convenient at this point to present a few particulars of Mr. Temple’s career, closely associated as that gentleman was with the subject of our history. After leaving Edinburgh he sustained the loss of a considerable fortune through the embarrassments of his father. Proceeding to the University of Cambridge, he took the degree of LL.B., and soon afterwards entered into orders. In 1767 he was preferred to the Rectory of Mamhead, Devonshire, which, added to the Vicarage of St. Gluvias, Cornwall, brought him, with the remains of his private fortune, an income of £500 a year. In youth he afforded proof of original power; he was a considerable politician, and an excellent classical scholar. He composed neatly; his character[8] of the poet Gray, with whom he was acquainted, has been quoted approvingly by Dr. Mason, his biographer, and likewise by Dr. Johnson. He published an essay on the studies of the clergy, another “On the Abuse of Unrestrained Power,” and “A Selection of Historical and Political Memoirs;” but none of these compositions were much sought after. He died on the 8th August, 1796, surviving our author little more than a year. He was oppressed by an habitual melancholy, which the untoward temper of his wife served materially to intensify. He has been described as “Boswell’s faithful monitor;” he was scarcely so, for his remonstrances were feeble. Had he reproved sternly he might have been of some service.

In a letter to Mr. Temple dated 29th July, 1758, Boswell informs him that he had been introduced to Mr. Hume, whom he thus describes:—“He is a most discreet, affable man, as ever I met with, and has really a great deal of learning, and a choice collection of books. He is indeed an extraordinary man,—few such people are to be met with now-a-days. We talk a great deal of genius, fine language, improving our style, &c., but I am afraid solid learning is much wore out. Mr. Hume, I think, is a very proper person for a young man to cultivate an acquaintance with. Though he has not perhaps the most delicate taste, yet he has applied himself with great attention to the study of the ancients, and is likewise a great historian, so that you are not only entertained in his company, but may reap a great deal of useful instruction.”

When Mr. Temple proceeded to Cambridge he reported to his Edinburgh friend that he was studying in earnest. In his reply, dated 16th December, 1758, Boswell describes his own studies:—“I can assure you,” he writes, “the study of the law here is a most laborious task.... From nine to ten I attend the[9] law class; from ten to eleven study at home; and from one to two attend a college [class] upon Roman antiquities; the afternoon and evening I always spend in study. I never walk except on Saturdays.” Thanking his friend for the perusal of a MS. poem he adds, “To encourage you I have enclosed a few trifles of my own.... I have published now and then the production of a leisure hour in the magazines. If any of these essays can give entertainment to my friend, I shall be extremely happy.”

On the importance of religion Boswell reciprocated his friend’s sentiments. After informing him that the continuance of his friendship made him “almost weep with joy,” he proceeds, “May indulgent Heaven grant a continuance of our friendship! As our minds improve in knowledge may the sacred flame still increase, until at last we reach the glorious world above when we shall never be separated, but enjoy an everlasting society of bliss. Such thoughts as these employ my happy moments, and make me—

‘Feel a secret joy

Spring o’er my heart, beyond the pride of kings.’”

After a reference to companionship he adds, “I hope by Divine assistance, you shall still preserve your amiable character amidst all the deceitful blandishments of vice and folly.”

In the same letter Boswell informed Mr. Temple that he had fallen desperately in love. The object of his affection was a Miss W—— t, for so he disguises her name—a reticence in matters of the heart which he does not evince subsequently. After expatiating on the lady’s charms and angelic qualities, especially her “just regard for true piety and religion,” he remarks that “she is a fortune of thirty thousand pounds.” With so large a dowry, he feels that she might be difficult to win, but he conceives that “a youth of his turn has a better[10] chance to gain the affections of a lady of her character than of any other.” He adds complacently, “As I told you before, my mind is in such an agreeable situation, that being refused would not be so fatal as to drive me to despair.” He sums up by assuring his correspondent that he had entrusted the secret of his passion only to another whose name was “Love.”

Mr. Love was one of Boswell’s early heroes. A native of England, he was originally connected with Drury Lane Theatre, but for some cause he left London and sojourned at Edinburgh. There he at first practised private theatricals, but afterwards became a teacher of elocution. He read with Miss W—— t, and also with Boswell, though at different hours, and advised the latter to look after the pretty heiress. Boswell took the hint; but the dream soon passed away, for the name of the rich beauty does not reappear.

To his young friend Mr. Love administered more useful counsel by advising him to cultivate an easy style of composition. To accomplish this he recommended him to keep a journal or commonplace-book, and daily to record in it notes of conversations, and of more remarkable occurrences. Boswell acted on Mr. Love’s suggestion. Writing to Mr. Temple, he reports that having gone with his father to the Northern Circuit, he travelled in a chaise with Sir David Dalrymple the whole way, and that he kept an exact journal at the particular desire of his friend Mr. Love, and sent it to him in sheets, by every post. Such was Boswell’s first effort in journal-making; it was next to be practised on Paoli, and latterly, with unprecedented success, on Dr. Johnson. As to Mr. Love, it may be remarked that he compensated himself for his early counsel by sponging his pupil. “Love is to breakfast with me to-morrow,” wrote Boswell to Mr. Temple in July 1763. “I hope I shall get him to pay me up some more of[11] what he owes me. Pray, is pay up an English phrase, I know pay down is?”

Sir David Dalrymple, Bart., better known by his judicial title of Lord Hailes, was now an Advocate Depute,[8] one of the faculty specially retained by the Crown for arraigning offenders in the Justiciary Court. An able lawyer, he had already afforded evidence of his ability and accurate scholarship in several separate publications and in various contributions to the periodicals. Possessing a fund of information which he communicated with much suavity of manner, Boswell hailed him as his Mæcenas. Having enrolled him among his divinities, he was disposed to idolize likewise all those whom he approved. Of these the most conspicuous was Dr. Samuel Johnson, whose existence was first made known to him in a post-chaise conversation. He was delighted to learn that he still lived, was the centre of a literary circle, had composed a literary medley styled the Rambler, and had edited a dictionary. As Sir David expatiated on his learning and his virtues, Boswell resolved that one day Johnson should have a place among his gods.

In November, 1759, Boswell entered the University of Glasgow as a student of civil law; he also attended the lectures of Dr. Adam Smith on moral philosophy and rhetoric. His evenings were spent in places of public amusement. From Mr. Love he had contracted a fancy for dramatic art, which in the absence of a licensed theatre he could not gratify in the capital. With more enlightened views the merchants of[12] Glasgow tolerated theatrical representations, obtaining on their boards such talent as their provincial situation could afford. Among those who sought a livelihood at the Glasgow theatre was Francis Gentleman, a native of Ireland, and originally an officer in the army. This amiable gentleman sold his commission in the hope of obtaining fame and opulence as a dramatic author; but disappointed in obtaining a patron, he attempted to subsist as an actor. He was entertained by Boswell, who encouraged him to publish an edition of Southern’s tragedy of “Oroonoco,” himself accepting the poetical dedication. The dedicatory verses closed thus:—

“But, where, with honest pleasure, she can find

Sense, taste, religion, and good nature joined,

There gladly will she raise her feeble voice,

Nor fear to tell that Boswell is her choice.”

Boswell’s patronage did not avail the unfortunate player. He was compelled to leave Glasgow; thereafter he removed from place to place, “experiencing all the hardships of a wandering actor, and all the disappointments of a friendless author.” He died in September, 1784.

At Glasgow, while spending his week-day evenings in places of amusement, Boswell began to frequent on Sundays the services of the Church of Rome. Before the end of the College session he had resolved to embrace the Catholic faith, and to qualify himself for orders in the Romish Church. These vagaries were so distressing to his parents that he was recalled to Edinburgh. He consented to abandon his sacerdotal aspirations, provided he was allowed to substitute for the law the profession of arms. In March 1760 his father accompanied him to London in order to procure him a commission in the Guards. They waited on the Duke of Argyll, who, according to Boswell’s narrative, keenly discommended the military proposal. “My lord,” said[13] the Duke, “I like your son; this boy must not be shot at for three shillings and sixpence a day.” Lord Auchinleck soon after returned to Edinburgh.

Boswell was allowed to remain in London. His religious views were opposed to his interests in the North, and it was evident that he would not be restrained from avowing his belief in public. It was therefore advisable that he should meanwhile reside in London. At the request of his father, Lord Hailes introduced him to Dr. Jortin, in the hope that that eminent divine would lead him to conform to the doctrines of the English Church. The following letter from Dr. Jortin to Lord Hailes, dated 27th April, 1760, would imply that Boswell had already, amidst the gaieties of London, ceased to concern himself with ecclesiastical questions:—

“Your young gentleman[9] called at my house on Thursday noon, April 3. I was gone out for the day, and he seemed to be concerned at the disappointment, and proposed to come the day following. My daughter told him that I should be engaged at church, it being Good Friday. He then left your letter, and a note with it for me, promising to be with me on Saturday morning. But from that time to this I have heard nothing of him. He began, I suppose, to suspect some design upon him, and his new friends and fathers may have represented me to him as an heretic and an infidel, whom he ought to avoid as he would the plague. I should gladly have used my best endeavours upon this melancholy occasion, but, to tell you the truth, my hopes of success would have been small. Nothing is more intractable than a fanatic. I heartily pity your good friend. If his son be really sincere in his new superstition, and sober in his morals, there is some comfort in that, for surely a man may be a papist and an honest man. It is not to be expected that the son should feel much for his father’s sorrows. Religious bigotry eats up natural affection, and tears asunder[14] the dearest bonds. Yet, if I had an opportunity I should have touched that string, and tried whether there remained in his breast any of the veteris vestigia flammæ.”

To his early attachment to the Romish Church, Boswell afterwards refers only once. In a letter addressed to Mr. Temple in November, 1789, he remarks that his “Popish imagination induces him to regard his correspondent’s friendship as a kind of credit on which he may in part repose.”

With his father Boswell was not candid in his professed military ardour. In seeking a commission in the Guards, he informed Mr. Temple[10] his desire was “to be about court, enjoying the happiness of the beau monde and the company of men of genius.” As to military zeal he afterwards announced in a pamphlet,[11] that he was troubled with a natural timidity of personal danger, which cost him some philosophy to overcome.

He protracted his residence in London for a whole year. For some time he resided with Alexander, tenth Earl of Eglinton, a warm friend of the Auchinleck family. By his lordship he was introduced “into the circle of the great, the gay, and the ingenious.” Having been presented to the Jockey Club, and carried to Newmarket, he was deeply moved by the events of the racecourse. Retiring to the coffee-room he composed a poem, making himself the theme, though in styling himself “The Cub at Newmarket” he gratified his egotism by the forfeiture of dignity. Presented by Lord Eglinton to the Duke of York, he invited his Royal Highness to listen to his poem, and ventured to offer him the dedication. The Duke accepted what it would have been ungracious to refuse, and Boswell[15] printed his poem with an epistle dedicatory, in which he “let the world know that this same Cub has been laughed at by the Duke of York, had been read to his Royal Highness by the genius himself, and warmed by the immediate beams of his kind indulgence.” Boswell thus describes himself:—

“Lord * * * * n, who has, you know,

A little dash of whim or so;

Who through a thousand scenes will range,

To pick up anything that’s strange,

By chance a curious cub had got,

On Scotia’s mountains newly caught;

And after driving him about

Through London, many a diff’rent route,

The comic episodes of which

Would tire your lordship’s patience much;

Newmarket Meeting being near,

He thought ’twas best to have him there.

*****

He was not of the iron race

Which sometimes Caledonia grace;

Though he to combat could advance,

Plumpness shone in his countenance;

And belly prominent declared

That he for beef and pudding cared;

He had a large and pond’rous head,

That seemed to be composed of lead;

From which hung down such stiff, lank hair,

As might the crows in autumn scare.”

For some time Lord Eglinton was amused by the juvenile ardour and vivacity of his guest. At length, overcome by his odd ways, he checked in plain terms his visitor’s vanity and recklessness. The admonition was probably unheeded, for his Lordship seems to have withdrawn his patronage. His own career was cut short by a sad and memorable occurrence; he was shot on his own estate by a poacher, whose firelock he had forcibly seized. He died on the 25th October, 1769.

In London, Boswell got acquainted with the poet Derrick, who became his companion and guide. Derrick was in his thirty-sixth year. A native of Dublin, he had been apprenticed to a linendraper, but speedily relinquished the concerns of trade. In 1751 he proceeded to London and tried his fortune on the stage. He next sought distinction as a poet. Introduced to Dr. Johnson, he obtained a share of the lexicographer’s regard; but, while entertaining affection for him as a man, the moralist reproved his muse and condemned his levity. Writing to Mr. Temple, Boswell refers to some of Derrick’s verses as “infamously bad.” When Nash died, Derrick succeeded him as master of ceremonies at Bath. He died there about the year 1770.

In April, 1761, Boswell, in reluctant obedience to his father’s wishes, returned to Edinburgh. Writing to Mr. Temple on the 1st May, he implores his friend’s commiseration. “Consider this poor fellow [meaning himself] hauled away to the town of Edinburgh, obliged to conform to every Scotch custom, or be laughed at—‘Will you hae some jeel? oh, fie! oh, fie!’—his flighty imagination quite cramped, and he obliged to study ‘Corpus Juris Civilis;’ and live in his father’s strict family; is there any wonder, sir, that the unlucky dog should be somewhat fretful? Yoke a Newmarket courser to a dung-cart, and I’ll lay my life on’t he’ll either caper or kick most confoundedly, or be as stupid and restive as an old battered post-horse.” In the same letter Boswell acknowledges that his behaviour in London had been the reverse of creditable. On his return to Edinburgh, he contributed to a local periodical some notes on London life. This narrative attracted the notice of John, thirteenth Lord Somerville, a nobleman of singular urbanity and considerable literary culture. His lordship invited the author to his table, commended his composition, and urged him to perseverance. Lord[17] Somerville died in 1765. Boswell cherished his memory with affection.

At Edinburgh, Boswell was admitted into the literary circles. He dined familiarly with Lord Kames, was the disciple and friend of Sir David Dalrymple, and passed long evenings with Dr. Robertson and David Hume. His passion for the drama gained force. At this period there was no licensed theatre in Edinburgh, and among religious families playgoing was proscribed. Just five years had elapsed since the Rev. John Home, minister of Athelstaneford, had, on account of taking part in the private representation of his tragedy of “Douglas,” been constrained to resign his parochial charge. The popular prejudice against theatricals was a sufficient cause for our author falling into the opposite extreme; he threw his whole energies into a movement which led six years afterwards to a theatre being licensed in the capital.

Boswell’s chief associate in theatrical concerns was Mr. David Ross, a tragedian who sometime practised on the London boards, but who, like our author’s friends, Messrs. Love and Gentleman, had been driven northward by misfortune. A native of London, Mr. Ross was of Scottish parentage. His father had practised in Edinburgh as a Writer to the Signet; he settled in London in 1722 as a Solicitor of Appeals. Born in 1728, David, his only son, was sent to Westminster School. There he committed some indiscretion, which led to his expulsion and his father’s implacable resentment. For some years he earned subsistence as a commercial clerk, but obtaining from Quin lessons in the dramatic art, he came on Covent Garden stage in 1753, where he acquired a second rank as a tragedian. Irregular habits interfered with his advancement, and he proceeded to Edinburgh, in the hope of obtaining professional support. He became Master of Revels, and gave private entertainments[18] which were appreciated and patronized. At length, on the 9th December, 1767, he was privileged to open the first licensed theatre in the capital. Boswell, at his request, composed the ‘prologue;’ the verses, now unhappily irrecoverable, were described by Lord Mansfield as “witty and conciliating.” The theatre proved a success, and the player soon afterwards acquired by marriage considerable emolument. He accepted as his wife Fanny Murray, who had in a less honourable connexion been associated with a deceased nobleman, receiving with her an annuity of two hundred pounds. Ross obtained a further advance of fortune in a manner singularly unexpected. On his death-bed his father made a will, excluding him from any share of his property, and cruelly stipulating that his sister “should pay him one shilling annually, on the first day of May, his birthday, to remind him of his misfortune in being born”! On the plea that by the law of Scotland, a person could not bequeath an estate by mere words of exclusion without an express conveyance of inheritance, Ross obtained a reduction of the settlement, and on a decision by the House of Lords got possession of six thousand pounds. He now retired from the Edinburgh theatre, and renewed his engagements at Covent Garden; but he soon became a victim to reckless improvidence. To the close Boswell cherished his society, though he did not venture to introduce him into literary circles. He died in September, 1790. The following extract from Boswell’s letter to Mr. Temple, dated 16th September, 1790, will close the narrative of his career:—

“My old friend Ross, the player, died suddenly yesterday morning. I was sent for, as his most particular friend in town, and have been so busy in arranging his funeral, at which I am to be chief mourner, that I have left myself very little time—only about ten minutes. Poor Ross! he was an unfortunate[19] man in some respects; but he was a true bon vivant, a most social man, and never was without good eating and drinking, and hearty companions. He had schoolfellows and friends who stood by him wonderfully. I have discovered that Admiral Barrington once sent him £100, and allowed him an annuity of £60 a year.”

Among those of his own age and standing who supported Boswell in managing theatricals at Edinburgh was the Honourable Andrew Erskine, youngest son of Alexander, fifth Earl of Kellie. This young gentleman, then a lieutenant in the 71st regiment, was abundantly facetious, and composed respectable verses. Replying to a letter from Boswell, dated at Auchinleck on the 25th August, Erskine expressed himself in verse, and letters were exchanged on both sides for a considerable period. Boswell meanwhile resolved to lay further claim to the poet’s bays. In November he issued a poem in sixteen Spenserian stanzas, covering a like number of printed pages, entitled “An Ode to Tragedy, by a Gentleman of Scotland.” It was characteristically inscribed to himself—the epistle dedicatory proceeding thus:—

“The following ode which courts your acceptance is on a subject grave and solemn, and therefore may be considered by many people as not so well suited to your volatile disposition. But I, sir, who enjoy the pleasure of your intimate acquaintance, know that many of your hours of retirement are devoted to thought, and that you can as strongly relish the productions of a serious muse as the most brilliant sallies of sportive fancy.”

Writing to Erskine on the 17th December, Boswell further enlarges on his own personal qualities. “The author of ‘The Ode to Tragedy,’” he proceeds, “is a most excellent man; he is of an ancient family in the west of Scotland, upon which he values[20] himself not a little. At his nativity appeared omens of his future greatness. His parts are bright, and his education has been good. He has travelled in post-chaises miles without number. He eats of every good dish, especially apple pie. He drinks old hock. He has a very fine temper. He is somewhat of a humourist, and a little tinctured with pride. He has a good manly countenance, and owns himself to be amorous. He has infinite vivacity, yet is observed at times to have a melancholy cast. He is rather fat than lean, rather short than tall, rather young than old. His shoes are neatly made, and he never wears spectacles.”

In 1760, Mr. Erskine edited the first volume of a work in duodecimo, entitled “A Collection of Original Poems, by the Rev. Mr. Blacklock and other Scotch gentlemen.” This publication contained compositions by Mr. Blacklock, Dr. Beattie, Mr. Gordon of Dumfries, and others; it was published by Alexander Donaldson,[12] an Edinburgh bookseller, and was intended as the first of a series of three volumes. The second volume was considerably delayed, owing to Mr. Erskine’s absence with his regiment, and on Boswell were latterly imposed the editorial labours. As contributors Erskine and Boswell were associated with Mr. Home, author of Douglas, Mr. Macpherson, editor of Ossian, and others. Of twenty-eight pieces from Boswell’s pen one is subjoined, eminently characteristic of its author.

“B——, of Soapers[13] the king,

On Tuesdays at Tom’s does[14] appear,

And when he does talk, or does sing,

To him ne’er a one can come near

For he talks with such ease and such grace,

That all charm’d to attention we sit,

And he sings with so comic a face,

That our sides are just ready to split.

“B—— is modest enough,

Himself not quite Ph[oe]bus he thinks,

He never does flourish with snuff,

And hock is the liquor he drinks.

And he owns that Ned C——t,[15] the priest,

May to something of honour pretend,

And he swears that he is not in jest,

When he calls this same C——t his friend.

“B—— is pleasant and gay,

For frolic by nature design’d;

He heedlessly rattles away

When the company is to his mind.

‘This maxim,’ he says, ‘you may see,

We can never have corn without chaff;’

So not a bent sixpence cares he,

Whether with him or at him you laugh.

“B—— does women adore,

And never once means to deceive,

He’s in love with at least half a score;

If they’re serious he smiles in his sleeve.

He has all the bright fancy of youth,

With the judgment of forty and five.

In short, to declare the plain truth,

There is no better fellow alive.”

Writing to Erskine on the 8th December, 1761, Boswell remarks that the second volume of the “Collection” was about to appear, adding that his friend would “make a very good figure, and himself a decent one.” But the public, while not disapproving the strain of the known authors, condemned the levity of the anonymous contributors, and thrust aside the book. The publishing enterprise was ruined, and the projected third volume did not appear.

Boswell determined to leave Edinburgh, assuring his father that a military life was alone suited to his tastes. In a letter to Erskine, dated the 4th of May, he proceeds:—

“My fondness for the Guards must appear very strange to you, who have a rooted antipathy at the glare of scarlet. But I must inform you that there is a city called London, for which I have as violent an affection as the most romantic lover ever had for his mistress. There a man may indeed soap his own beard, and enjoy whatever is to be had in this transitory state of things. Every agreeable whim may be fully indulged without censure. I hope, however, you will not impute my living in England to the same cause for which Hamlet was advised to go there, because the people were all as mad as himself.”[16]

Paternal remonstrances having proved unavailing, Boswell was permitted to return to the metropolis. From Parliament Place, Edinburgh, writing to Erskine on the 10th November, he informs him that “on Monday next he is to set out for London.” On the 20th November he writes from London, “If I can get into the Guards, it will please me much; if not, I can’t help it.”

Boswell brought from Scotland a recommendation to Charles,[23] Duke of Queensberry, the patron of Gay, but that nobleman took no part in his concerns. He again sought the field of authorship. He and Erskine had corresponded on a variety of topics, and he fancied that their letters might attract attention. The letters were printed in an octavo volume,[17] Boswell remarking in the preface, that he and his correspondent “have made themselves laugh, and hope they will have the same effect upon other people.” Erskine and Boswell were afterwards associated in writing “Critical Strictures” on Mallet’s tragedy of “Elvira,” acted at Drury Lane in the winter of 1762-3. In 1764, Erskine published a drama entitled “She’s not Him, and He’s not Her; a Farce in Two Acts, as it is performed in the Theatre in the Canongate.” In 1773 he issued “Town Eclogues,” a poem of twenty-two quarto pages, intended “to expose the false taste for florid description which prevails in modern poetry.”

From the 71st Erskine in 1763 exchanged into the 24th Regiment, in which he became Captain. Retiring from the army, he settled at Edinburgh. There he resided after 1790 with his sister, Lady Colville, at Drumsheugh, near the Dean Bridge. He was an extraordinary pedestrian, and walked nearly every morning to Queensferry, about ten miles distant, where he breakfasted at Hall’s Inn. He dispensed with attendance, and when he had finished his repast, left payment under a plate. He was of a tall, portly form, and to the last wore gaiters and a flapped vest. Though satirical with his pen, he was genial and humorous in conversation. He was an early admirer and occasional correspondent of the poet Burns. Like his brother, “the musical Earl of Kellie,” he was a lover of Scottish melodies, and was one of a party of amateurs who[24] associated with Mr. George Thomson in designing his “Collection of Scottish Airs.” He actively assisted Mr. Thomson in the earlier stages of his undertaking. Several songs from his pen, Burns, in a letter to Mr. Thomson, written in June, 1793, described as “pretty,” adding, his “Love song is divine.” The composition so described beginning “How sweet this lone vale,” became widely popular; but the opening stanza only was composed by him. He was one of the early friends of Archibald Constable, the eminent publisher, who, in an autobiographical fragment has described him as having “an excellent taste in the fine arts,” and being “the most unassuming man he had ever met.”[18] His habits were regular, but he indulged occasionally at cards, and was partial to the game of whist. Having sustained a serious loss at his favourite pastime he became frantic, and threw himself into the Forth, and perished. This sad event took place in September, 1793. In a letter to Mr. Thomson, dated October, 1791, Burns writes that the tidings of Erskine’s death had distressed and “scared” him.

From the day Sir David Dalrymple first named Dr. Samuel Johnson in the post-chaise, Boswell entertained a hope of forming the lexicographer’s acquaintance. On his former visit to London he had exerted some effort to procure an introduction. Derrick promised it, but lacked opportunity. During the summer of 1761, Thomas Sheridan lectured at Edinburgh on the practice of elocution, and charmed Boswell by descanting on Dr. Johnson’s virtues. Through Sheridan an introduction seemed easy, but Boswell on visiting him found that he and the lexicographer had differed. Boswell did not despair. He obtained leave to occupy his friend Mr. Temple’s chambers[25] in the Inner Temple, near Dr. Johnson’s residence, and adjoining his well-known haunts.

A further effort was necessary. Boswell ingratiated himself with Mr. Thomas Davies, bookseller, of No. 8, Russell Street, Covent Garden, formerly a player. Mr. Davies knew Dr. Johnson well, saw him frequently in his shop, and was privileged to entertain him at his table. To meet Boswell, the lexicographer was invited more than once, but as our author puts it, “he was by some unlucky accident or other prevented from coming to us.” In an unexpected manner Boswell at length attained his wishes. The occurrence must be described in his own words:—“At last, on Monday, the 16th of May, when I was sitting in Mr. Davies’ back parlour, after having drunk tea with him and Mrs. Davies,[19] Johnson unexpectedly came into the shop; and Mr. Davies having perceived him through the glass door in the room in which we were sitting advancing towards us, he announced his awful approach to me something in the manner of an actor in the part of Horatio, when he addresses Hamlet on the appearance of his father’s ghost,—‘Look, my lord, it comes!’ * * * Mr. Davies mentioned my name, and respectfully introduced me to him. I was much agitated; and recollecting his prejudice against the Scotch, of which I had heard much, I said to Davies, ‘Don’t tell where I come from.’ ‘From Scotland,’ cried Davies, roguishly. ‘Mr. Johnson,’ said I, ‘I do indeed come from Scotland, but I cannot help it.’ I am willing to flatter myself that I meant this as light pleasantry to soothe and conciliate him, and not as a humiliating abasement at the expense of my country. But however that might be, this speech was somewhat unlucky; for with that quickness of wit for which he was so remarkable he seized the expression[26] “come from Scotland,” which I used in the sense of being of that country; and as if I had said I had come away from it or left it, retorted, ‘That, sir, I find, is what a very great many of your countrymen cannot help.’ This stroke stunned me a good deal; and when we had sat down I felt myself not a little embarrassed, and apprehensive of what might come next. He then addressed himself to Davies: ‘What do you think of Garrick? He has refused me an order for the play for Miss Williams, because he knows the house will be full, and that an order would be worth three shillings.’ Eager to take any opening to get into conversation with him, I ventured to say, ‘Oh, sir, I cannot think Mr. Garrick would grudge such a trifle to you.’ ‘Sir,’ said he, with a stern look, ‘I have known David Garrick longer than you have done, and I know no right you have to talk to me on this subject.’ Perhaps I deserved this check; for it was rather presumptuous in me, an entire stranger, to express any doubt of the justice of his animadversion upon his old acquaintance and pupil. I now felt myself much mortified, and began to think that the hope which I had long indulged of obtaining his acquaintance was blasted. And in truth, had not my ardour been uncommonly strong, and my resolution uncommonly persevering, so rough a reception might have deterred me for ever from making any further attempts. Fortunately, however, I remained upon the field not wholly discomfited, and was soon rewarded by hearing some of his conversation.” Boswell closes his narrative thus:—“I had for a part of the evening been left alone with him, and had ventured to make an observation now and then, which he received very civilly, so that I was satisfied that though there was a roughness in his manner, there was no ill-nature in his disposition. Davies followed me to the door, and when I complained to him a little of the hard blows which the great[27] man had given me, he kindly took upon him to console me by saying, ‘Don’t be uneasy. I can see he likes you very well.’”

Dr. Johnson regarded Boswell as an adventurer, who had come to London in quest of literary employment. Davies perceiving this, privately explained to him that Boswell was the son of a Scottish judge and heir to a good estate. “A few days afterwards,” writes Boswell, “I called on Davies, and asked him if he thought I might take the liberty of waiting on Mr. Johnson at his chambers in the Temple. He said I certainly might, and that Mr. Johnson would take it as a compliment. So upon Tuesday, the 24th of May, after having been enlivened by the witty sallies of Messieurs Thornton, Wilkes, Churchill, and Lloyd, with whom I had passed the morning, I boldly repaired to Johnson. His chambers were on the first floor of No. 1, Inner Temple Lane, and I entered them with an impression given me by the Rev. Dr. Blair, of Edinburgh, who had been introduced to me not long before and described his having ‘found the giant in his den,’ an expression which, when I came to be pretty well acquainted with Johnson, I repeated to him, and he was diverted at this picturesque account of himself. * * * He received me very courteously; but it must be confessed that his apartment and furniture and morning dress were sufficiently uncouth. His brown suit of clothes looked very rusty; he had on a little old shrivelled unpowdered wig, which was too small for his head; his shirt-neck and knees of his breeches were loose; his black worsted stockings ill drawn up, and he had a pair of unbuckled shoes by way of slippers. But all these slovenly particularities were forgotten the moment that he began to talk. Some gentlemen, whom I do not recollect, were sitting with him; and when they went away I also rose, but he said to me, ‘Nay, don’t go.’ ‘Sir,’ said I, ‘I am afraid that I intrude upon you. It is benevolent to allow me to sit and[28] hear you.’ He seemed pleased with this compliment, which I sincerely paid him, and answered, ‘Sir, I am obliged to any man who visits me.’ * * * Before we parted he was so good as to promise to favour me with his company one evening at my lodgings; and as I took my leave, shook me cordially by the hand. It is almost needless to add that I felt no little elation at having now so happily established an acquaintance of which I had been so long ambitious.”

The evident sincerity of Boswell’s respect pleased and flattered Dr. Johnson. He listened to details of literary life in Edinburgh, and was gratified to learn that certain Scotsmen appreciated his learning. He visited Boswell in his chambers, and invited him to the Mitre Tavern, where afterwards they frequently supped, and drank port till long after midnight. At one of these festive meetings Boswell related the story of the post-chaise, and expatiated on the merits of Sir David Dalrymple with the ardour of a hero worshipper. Dr. Johnson toasted Sir David in a bumper as “a man of worth, a scholar, and a wit.” He added, “I have, however, never heard of him except from you; but let him know my opinion of him, for as he does not show himself much in the world, he should know the praise of the few who hear of him.” On the 2nd of July, Boswell communicated with Sir David Dalrymple in these terms:[20]—

“I am now upon a very good footing with Mr. Johnson. His conversation is instructive and entertaining. He has a most extensive fund of knowledge, a very clear expression, and much strong humour. I am often with him. Some nights ago we supped by ourselves at the Mitre Tavern, and sat over a sober bottle till between one and two in the morning. We talked a good deal of you. We drank your health, and he desired me to tell you so. When I am in his company I am rationally happy,[29] I am attentive and eager to learn, and I would hope that I may receive advantage from such society.”

To Boswell’s letter, in its allusion to Dr. Johnson, Sir David Dalrymple made the following answer:—[21]

“It gives me pleasure to think that you have obtained the friendship of Mr. Samuel Johnson. He is one of the best moral writers which England has produced. At the same time I envy you the free and undisguised converse with such a man. May I beg you to present my best respects to him, and to assure him of the veneration which I entertain for the author of the ‘Rambler’ and of ‘Rasselas.’”

On the 15th July Boswell thus communicated with Mr. Temple:—

“I had the honour of supping tête-à-tête with Mr. Johnson last night; by-the-bye, I need not have used a French phrase. We sat till between two and three. He took me by the hand cordially, and said, ‘My dear Boswell, I love you very much.’ Now, Temple, can I help indulging vanity?”

After quoting a portion of Sir David Dalrymple’s letter, he proceeds:—

“Mr. Johnson was in vast good humour, and we had much conversation. I mentioned Fresnoy to him, but he advised me not to follow a plan, and he declared that he himself never followed one above two days. He advised me to read just as inclination prompted me, which alone, he said, would do me any good; for I had better go into company than read a set task. Let us study ever so much, we must still be ignorant of a good deal. Therefore the question is, what parts of science do we want to know? He said, too, that idleness was a distemper which I ought to combat against, and that I should prescribe to myself five hours a day, and in these hours gratify whatever literary desires may spring up. He is to give me his advice as[30] to what books I should take with me from England. I told him that the Rambler shall accompany me round Europe, and so be a Rambler indeed. He gave me a smile of complacency.”

The tête-à-tête with Dr. Johnson on the 14th of July, so described to Mr. Temple, also forms the subject of a letter to Sir David Dalrymple. That letter proceeds thus:—[22]

“On Wednesday evening, Mr. Johnson and I had another tête-à-tête at the ‘Mitre.’ Would you believe that we sat from half an hour after eight till between two and three! He took me cordially by the hand and said, ‘My dear Boswell! I love you very much.’ Can I help being somewhat vain? * * * He advises me to combat idleness as a distemper, to read five hours every day, but to let inclination direct me what to read. He is a great enemy to a stated plan of study. He advises me when abroad to go to places where there is most to be seen and learnt. He is not very fond of the notion of spending a whole winter in a Dutch town. He thinks I may do much more by private study than by attending lectures. He would have me to perambulate (a word in his own style) Spain. He says a man might see a good deal by visiting their inland towns and universities. He also advises me to visit the northern kingdoms, where more that is new is to be seen than in France and Italy, but he is not against my seeing these warmer regions.”

These allusions to foreign travel refer to a proposal by Lord Auchinleck that his son should study civil law at Utrecht, and in which Boswell was disposed to acquiesce, believing that in thus gratifying his father’s wishes he might be permitted before returning home to visit the principal countries of the Continent.