—"Udrallo il bel paese,

Ch' Apennin parte, e 'l mar circonda e l'Alpe."

PETRARCA.

Whatever defects may exist in my attempt at rendering "Corinne" into English, be it remembered, that we have many words for one meaning—in French there are several significations for the same word. Repetition, an elegance in French, is a barbarism in English. Thus I had to contend with a tautology almost unmanageable, and even a reiteration of the same sentiments. Sentences, harmonious in French, lost all agreeable cadence, until entirely reconstructed. Madame de Staël's diffuse manner obliged me also to transpose pretty freely. I found, in so doing, many self-contradictions, some of which I could not efface. Her boldness of condensation, too, and love of vague, mysterious sublimity, often left me in doubt as to what might be hidden beneath the dazzling veil of her eloquence. It may appear profanation to have altered a syllable; but, having been accustomed to consult the taste of my own country, I could not outrage it by being more literal. I have taken the liberty of making British peasants and children speak their native idiom, and have added a few explanatory notes; occasionally availing myself of quotations from more recent authorities than that of the Baroness. Lest I should unconsciously have committed any great mistake, be it known that the printers of her "eighth corrected and revised edition" gave Corinne a military instead of a literary career, and made the Roman mob throw handfuls of bon mots into the carriages during the carnival.

Miss Landon had kindly undertaken to render the lyric portions of the work; but we feared for awhile, that our own Improvisatrice would be prevented by circumstances from gracing the volume by her name. I, therefore, translated Corinne's compositions into rhyme. Only one of my essays, however, "The Fragment of Corinne's Thoughts," was required. I am conscious of its imperfect regularity; but, having no poetical reputation at stake, I throw myself on the mercy of my judges.

ISABEL HILL.

6, CECIL STREET, STRAND.

Madame de Staël—Her Infancy and Education—Her Marriage—Her Personal Appearance—The Revolution—Her First Meeting and Conversation with Bonaparte—Interview with Josephine—Her Portrait and Character—Her Repartees—Exile—Delphine—Auguste de Staël and Napoleon—Private Theatricals—Corinne—Police Interference—Travels in Foreign Countries—Her Illness and Death—Effect of Napoleon's Persecution upon the Literary Position of Madame de Staël.

Jacques Necker, the father of Madame de Staël, a Genevese and a Protestant, was at the birth of his daughter Annie-Louise-Germaine Necker, in 1766, a clerk in a banking-house at Paris. He had married M'lle Curchod, a Swiss like himself, and who had, some years before, been the object of the first and last love of Gibbon the historian. Madame Necker undertook the education of Louise, plied her with books and tasks, and introduced her, even in infancy, to her own circle of brilliant and accomplished men. "At the age of eleven," writes a lady who was at the time her companion, "she spoke with a warmth and facility which were already eloquent. In society she talked but little, but so animated was her face that she appeared to converse with all. Every guest at her mother's house addressed her with some compliment or polite speech; she replied with ease and grace." She was encouraged to write, and her youthful productions were read in public, and some of them were even printed. This process of education, while it rendered the subject of it rather brilliant than profound, and encouraged vanity and a love of display, broke down her health, and the physicians ordered her to retire to the country, and to renounce all mental application. Her mother, disappointed and discouraged, ceased to take the same interest in her talents and progress; this indifference led Louise to attach herself more closely to her father, and developed in her what became through life her ruling passion—filial affection.

In 1776, Necker, who had in the meantime become the partner of his late employer, and had attracted attention by an essay on the corn laws, was considered by the masses as the only person capable of saving the country from bankruptcy. He was, therefore, appointed to control the finances, being the first Protestant who had held office since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. One of his acts, five years afterward, having excited clamor among the royalists, an anonymous pamphlet appeared, in which his defence was warmly espoused and the propriety of his conduct successfully asserted. Necker detected his daughter's style in this production, and she acknowledged its authorship, being then fifteen years old. Necker resigned office, and retreated with his family to Coppet, on the borders of the Lake of Geneva.

Madame de Genlis saw M'lle Necker for the first time, when the latter was sixteen. She thus speaks of her in her memoirs: "This young lady was not pretty; her manner was very animated, and she talked a great deal, too much indeed, though always with wit and discernment. I remember that I read one of my juvenile plays to Madame Necker, her daughter being present. I cannot describe the enthusiasm and the demonstrations of M'lle Louise, while I was reading. She wept, she uttered exclamations at every page, and constantly kissed my hands. Her mother had done wrong in allowing her to pass three-quarters of her time with the throng of wits who continually surrounded her, and who held dissertations with her upon love and the passions."[1]

At the age of twenty, Louise married Baron de Staël-Holstein, the Swedish ambassador at the court of France. She sought neither a lover nor a friend in her husband; she treated marriage as a convenience, and became a wife in order to obtain that liberty and independence which were denied her as a young lady. She required that her husband should be noble and a Protestant, and as in addition to these essentials Baron de Staël was an agreeable and an honorable man, and engaged never to compel her to follow him to Sweden, she consented to marry him. In the same year, 1786, a failure of the crops, and the consequent distress of the poorer classes, compelled the king to recall Necker to the administration of the finances.

Madame de Staël is thus described, at the age of twenty-five, by a writer who, to justify the peculiar and oriental extravagance of his style, assumed the character of a Greek poet: "Zulmé advances; her large dark eyes sparkle with genius; her hair, black as ebony, falls on her shoulders in wavy ringlets; her features are more striking than delicate, and express superiority to her sex. 'There she is,' all exclaim when she appears, and at once become breathless. When she sings, she extemporizes the words of her song, the ecstasy of improvisation animates her face, and holds the audience in rapt attention. When the song ceases, she talks of the great truths of nature, the immortality of the soul, the love of liberty, of the fascination and danger of the passions. Her features meanwhile wear an expression superior to beauty; her physiognomy is full of play and variety. When she ceases, a murmur of approbation thrills through the room; she looks down modestly; her long lashes sink over her flashing eyes, and the sun is clouded over."

The Revolution now advanced with rapid steps. Necker, whose capabilities as a financier have been generally acknowledged, was totally deficient in the higher qualities of the statesman. He sought to assume a middle position between the court and the people, but failing of success, was in consequence dismissed on the 11th of July, 1789. Paris rose in insurrection when this event became known, and on the 14th, the Bastille was in the hands of the people. The king was forced to send an order to recall Necker, who had left the country; this overtook him at Frankfort. "What a period of happiness," writes Madame de Staël, "was our journey back to Paris! I do not believe that a similar ovation was ever extended to a man not the sovereign of the country. Women, afar off in the fields, threw themselves on their knees, as the carriage passed: the most prominent citizens acted as postilions, and in many towns people detached the horses and dragged the carriage themselves. Oh, nothing can equal the emotions of a woman who hears the name of a beloved parent repeated with eulogy by a whole people!" This triumph was of short duration. In a little more than a year, Necker, who had opposed some of the more radical measures of reform in the National Assembly, lost the confidence of the people, resigned, and again withdrew to Switzerland. He was now accompanied by the revilings and maledictions of the populace, and even narrowly escaped with his life.

Madame de Staël remained at Paris, and speedily became involved in the intrigues of the day. Her salon was the rendezvous of the royalists and Girondins, and the scene of ardent political discussions. In the midst of the sanguinary excesses of '92, she fearlessly used her influence to shelter and save her friends. She took them to her own house, which, being the residence of an ambassador, she presumed would be inviolable. But one night the police appeared at the gate, and required that the doors be opened for a rigid search. Madame de Staël met them at the threshold, spoke to them of the rights of ambassadors and of the vengeance of Sweden, and by dint of wit, argument and intrepidity, persuaded them to abandon their designs. She was soon compelled to flee, however, and take refuge with her father at Coppet. Here she wrote and published an appeal in behalf of Marie Antoinette, and "Reflections on the Peace of 1783." The fall of Robespierre, in July, 1794, enabled her to return to Paris, whither she hastened, upon the news of his execution.

Her residence in the capital formed an event in the annals of society at that period. The most distinguished foreigners and the best men in France flocked around her. She gave her influence to the government of the Directory, being desirous of the establishment of some guaranty for the preservation of order and of individual security.

"Madame de Staël," says de Goncourt, "was a man of genius as early as the year 1795. It was by her hand, that France signed a treaty of alliance with existing institutions, and for a period accepted the Directory. Who obtained her the victory? Herself, with the aid of a friend who was the scribe of her dictation, the aid-de-camp and the notary-public of her thought, Benjamin Constant. The daughter of Necker forbade France to recall its line of kings: she retained the republic: she condemned the throne. She agitated victoriously in behalf of the maintenance of the representative system. The human right of victory was equivalent, with her, to the divine right of birth."[2]

The appearance of Bonaparte upon the stage of action produced a violent change in her life, pursuits and pleasures. She disliked and distrusted him from the first, and her drawing-room became an opposition club, or, as Napoleon himself described it, an arsenal of hostility. He, in turn, was vexed at her intellectual supremacy, and dreaded her influence. They first met at a ball given to Josephine, toward the close of the year 1797. She had long hunted him from place to place, for she was desirous of subjecting him, if possible, to the fascinations of her conversation, and he, avoiding the interview with consummate address, had always escaped her importunities. At the ball in question, he saw retreat to be impossible, and boldly seated himself in a vacant chair by her side. The following conversation, attributed to them, contains, in a concise form, the best of the authenticated sallies and repartees perpetrated by the illustrious interlocutors. After the usual preliminaries, the dialogue proceeded thus:

MADAME DE STAËL. Madame Bonaparte is a charming lady.

BONAPARTE. Any compliment passing through your lips, madame, acquires additional value.

ST. Ah! then you appreciate my opinion and my approbation? But you have doubted my capacity, you have thought me frivolous; nevertheless, my studies in diplomacy, in the history of courts——

BON. I implore Madame de Staël not to drag the Graces to the pillory of politics.

ST. I assure you, General, that your mythological compliment is totally lost upon me: I should prefer that you judge me worthy to talk reason with you.

BON. The right of your sex is to make us lose our reason: do not despise so excellent a privilege.

ST. General, I beg of you not to play with me as with a doll: I desire to be treated as a man.

BON. Then you would like to have me put on petticoats.

ST.—TO A GENTLEMAN INTERRUPTING HER.—Sir, be good enough to understand that I desire no assistance, though certainly my adversary is sufficiently powerful to render assistance necessary.

BON. Madame, it was to my aid that he was coming; my danger appalls him, and he was seeking to relieve me.

ST. In any case, I owe him small thanks for his tardy aid, since you confess that my victory seemed certain. He is a true friend, however; he stands by those he likes, even in their absence, when, usually, friendship slumbers.

BON. In that, friendship imitates its cousin—love.

ST.—NERVING HERSELF FOR AN EFFORT.—By what means, General, can an ordinary woman, without literary reputation, without superior genius, be sustained in the affection of a man she loves when separated from him by distance or a period of years? Memory, reduced to recalling her charms only, becomes gradually dim, and at last forgets, especially when the lover is a great man. But when the latter has had the good fortune to meet with a strong-minded woman, one worthy of sharing his laurels, and herself enjoying a high reputation, then the distance of time and space disappears, for it is the renown of both which serves as messenger between them, and it is through the hundred mouths of fame that each receives intelligence of the other.

BON. Madame, in what chapter of the work you are about to publish shall we read this brilliant passage?

ST. It has been the constant illusion of my soul.

BON. Ah, I understand; it is your hobby, after the manner of Sterne. So you are seeking the philosopher's stone?

ST. One would think, to hear you talk, that it is impossible to find it.

BON. There are two illusions in this world, though both flow from the same error; that of physical and that of moral alchemy. This idealistic philosophy leads to an abyss.

ST. One, nevertheless, which wit and sagacity may illumine with the rays of genius to its inmost recesses. Do you never build castles in the air, General? Do you never go and dwell in them? Do you never dream, to charm away the monotony of life?

BON. I leave dreams to sleep, and retain reason for my waking hours.

ST. Then you can never be either amused or surprised! You have a scouting party stationed to watch that outpost, the imagination?

BON. Wisdom counsels me to do so, and makes it my duty.

ST.—AFTER A MOMENT'S REFLECTION.—General, who, in your opinion, is the greatest of women?

BON. She who bears the most children.[3]

Madame de Staël turned slightly pale at this reply, and said no more. The General rose, bowed, and quitted the room. Both carried away from the interview the elements of mutual dislike and food for a life-long hostility. "Doubtless," says Lacretelle, "this last question was suggested by the vanity of the inquirer." And Bonaparte, eager to deprive the lady of the tribute she expected in his reply, made answer as we have described. "Certainly," adds Lacretelle, "it was impossible to rebuff a courtesy with greater rudeness and less discernment, for Madame de Staël was one of the powers of the day."[4]

One evening, early in the Consulate, Josephine met Madame de Staël at the house of Madame de Montesson. Bonaparte was to come somewhat later. Josephine, knowing his aversion for her, or fearing her seductions if she were successful in obtaining his attention, received her, as she advanced, in a manner so markedly cold, if not rude, that Madame de Staël recoiled without speaking, and retreated to the extremity of the room, where she dropped into a chair.

She remained for some time apart and alone. The pretty women took a malicious pleasure in the mortification of one of their own sex, while the gentlemen indulged in impertinent and unmanly remarks. At this moment, a young girl of extreme beauty and light airy step, with blond hair and blue eyes, and dressed entirely in white, left the group that had collected in the vicinity of Josephine, crossed the salon, and sat down by Madame de Staël. The latter, whose heart was as quick as her wit was ready, said to her, "You are as good as you are beautiful, my child."

"In what, pray, madame?" asked the young lady.

"In what?" returned Madame de Staël. "You ask me why I think you as kind as you are fair? Because you crossed this immense and deserted salon to come and sit by me. Upon my word, you are more courageous than I should have been."

"And yet, madame, I am naturally so timid that I should not dare to tell you my fears and trepidation: you would laugh at me, I am sure."

"Laugh at you!" exclaimed Madame de Staël, with moistened eyes and trembling voice; "laugh at you! never! never! I am your sister, henceforth, my dear, dear young friend! Will you tell me your Christian name?"

"Delphine, madame."

"Delphine! What a pretty name! I am very glad of it, for it will suit my purpose exactly. You must know, love, that I am writing a novel; and I mean it to bear your name. You shall be its god-mother; and you will find something in it which will remind you of to-day and of our acquaintance."

Madame de Staël kept her promise, and the passage in the novel of Delphine, in which the heroine, abandoned, is under similar circumstances relieved and sustained by Madame de R., was written in commemoration of this little domestic scene.[5]

Bonaparte soon entered the room, and ignorant of the treatment Madame de Staël had undergone from Josephine, accosted her graciously, and indeed took evident pains to restrain, during their conversation, his intuitive dislike of the petticoat politician.

Madame de Staël was now at the apogee of her talent and influence. Her conversation was not what is usually understood by the term. She did not require so much an interlocutor as a listener. Her improvisations were long and sustained pleas, if her object was to convince, or discursive though brilliant harangues, if she sought to display her wealth of thought and of words. Those that were accustomed to her ways rarely answered her, even if, in the heat of argument, she addressed them a question; well aware that it was rather to operate a diversion than to elicit a reply. She required the excitement of an audience, and her eloquence became richer and more rapid as the circle of her listeners widened. She preferred contradiction and dissent to a blind acceptance of her opinions, and the surest method of pleasing her was to adduce arguments that she might refute them, and which might suggest in her mind new trains of ideas. Controversy was her peculiar element, and she sometimes resorted to the charlatanical process of advocating two opposite opinions on the same occasion, in order to show the flexibility of her mind and the pliancy of her logic. In the season of foliage, she invariably carried in her hand a twig of poplar, which, when talking, she would turn and twist between her fingers; the crackling of this, she said, stimulated her brain. During the season when the poplar produces no leaves, she substituted for the twig a piece of rolled paper with which she was forced to be content, till the return of verdure. In winter, her flatterers and admirers always had a supply of these papers prepared, and presented her a quantity, on her arrival at a fête or a conversazione, that she might select her sceptre for the evening.[6] The famous twig of poplar is introduced in Gérard's portrait of Madame de Staël.[7]

She was never handsome, and without the extraordinary depth and brilliancy of her eyes, would have been a plain, if not an ugly woman. Her nose and mouth were homely, and only redeemed by her ever-varying expression. Her complexion was rough, her form massive rather than graceful, and indicated indolence rather than vivacity. Her hands were beautiful, and ill-natured people asserted that the poplar twig was a mere pretext for keeping them constantly in view. She dressed at all times without taste, and this defect became more conspicuous as she advanced in years, for at the age of forty-five she wore the colors and ornaments which would befit a young lady of twenty. Her coiffure was usually a turban, though this was not the prevailing fashion. Her partisans denied that there was any exaggeration in her toilet, though they allowed that she sought to be picturesque rather than fashionable.

Biography has preserved examples almost innumerable of the readiness of her wit and the profundity of her observation. The love of truth was one of her prominent characteristics. "I saw," she said "that Bonaparte was declining, when he no longer sought for the truth." She held long arguments on equality, and said on one occasion, "I would not refuse the opinion of the lowest of my domestics, if the slightest of my own impressions tended to justify his." Her respect for justice and moderation was evinced in her reply to the remark of a Bourbon after Napoleon's fall, to the effect that Bonaparte had neither talent nor courage: "It is degrading France and Europe too much, sir, to pretend that for fifteen years they have been subject to a simpleton and a poltroon!" She despised affectation, and said that she could not converse with an affected man or woman on account of the constant interruptions of a tedious third person—their unnatural and affected character. Of individuals accustomed to exaggerate, she said: "To put 100 for 10, why, there's no imagination in that." Her faith was sincere and unostentatious, and she would remark, after listening to lofty metaphysical discourses, "Well, I like the Lord's Prayer better than that." One of her best replies was made to Canning, in the Tuileries, after the exile of Napoleon: "Well, Madame de Staël, we have conquered you French, you see!" "If you have, sir, it was because you had the Russians and the whole continent on your side. Give us a tête-à-tête, and you will see!"

Madame de Staël's conduct as a wife was not irreproachable. Talleyrand was one of the first, though by no means the last, of her lovers. It was after his rupture with Madame de Staël that he entered upon his liaison with Madame Grandt, and it was this circumstance that led Madame de Staël to ask him the most unfortunate question of her life, for it gave him the opportunity of making the most comprehensive reply of his: "If Madame Grandt and I were to fall into the water, Talleyrand," she inquired, "which of us would you save first?" "Oh, madame," returned the minister, "YOU SWIM SO WELL!" She was revenged on him by drawing—though not very delicately—his character as a diplomatist: "He is so double-faced," she said, "that if you kick him behind, he will smile in front."

Bonaparte, early in the Consulate, sought through his brother Joseph, to attach Madame de Staël to his government; he might have done so, had he cared to conciliate her by expressing, or even feigning, deference to her talents and opinions. But he did not pursue the negotiation, and she continued her political discussions at her house, devoting her days to intrigues, and her evenings to epigrams; until Bonaparte, whose patience was exhausted, and who did not consider his power as yet fully established, directed his minister of police to banish her from Paris. She was ordered not to return within forty leagues of the city. He is said to have remarked, "I leave the whole world open to Madame de Staël, except Paris; that I reserve to myself." It was urged, too, that she had small claims to consideration; she was, though born in France, hardly a Frenchwoman, being the daughter of a Swiss and the wife of a Swede.

During a period of years, Madame de Staël remained under the ban of Bonaparte's displeasure, though, during a short interval, the intercessions of her father obtained permission for her to inhabit the capital. In 1803, she published her "Delphine," a work so immoral in its tendency that it incurred the censure of the critics and the public, and compelled the authoress to put forth a species of apology, which in its turn was considered lame and inconclusive. The character of Madame de Vernon, in "Delphine," was said to have been intended for Talleyrand, clothed in female garb.

Unable to endure the deprivation of her Parisian friends, Madame de Staël soon established herself at the distance of thirty miles from Paris. Bonaparte was told that her residence was crowded with visitors from the capital. "She affects," he said, "to speak neither of public affairs nor of me; yet it invariably happens that every one comes out of her house less attached to me than when he went in." An order for her departure was soon served upon her, and she set forth upon a pilgrimage through Germany.

In the last week of December, 1807, Napoleon, returning from Italy, stopped at the post-house of Chambéry, in Sardinia, for a fresh relay of horses. He was told that a young man of seventeen years, named Auguste de Staël, desired to speak with him. "What have I to do with these refugees of Geneva?" said Napoleon, tartly. He ordered him to be admitted, however. "Where is your mother?" said Napoleon, opening the conversation. "She is at Vienna, sire." "Ah, she must be satisfied now; she will have fine opportunities for learning German." "Sire, your majesty cannot suppose that my mother can be satisfied anywhere, separated from her friends and driven from her country. If your majesty would condescend to glance at these private letters, written by my mother, you would see, sire, what unhappiness her exile causes her." "Oh, pooh! that's the way with your mother. I do not say she is a bad woman; but her mind is insubordinate and rebellious. She was brought up in the chaos of a falling monarchy, and of a revolution running riot, and it has turned her head. If I were to allow her to return, six months would not pass before I should be obliged to shut her up in Bedlam, or put her under lock and key at the Temple. I should be sorry to do it, for it would make scandal, and injure me in public opinion. Tell your mother my mind is made up. As long as I live, she shall not again set foot in Paris."

"Sire, I am so sure that my mother would conduct herself with propriety that I pray you to grant her a trial, if it be only for six weeks." "It cannot be. She would make herself the standard-bearer of the faubourg St. Germain. She would receive visits, would return them, would make witticisms, and do a thousand follies. No, young man, no." "Will your majesty allow a son to inquire the cause of this hostility to his mother? I have been told it was the last work of my grandfather; I can assure your majesty that my mother had no hand in it." "Certainly, that book had its effect. Your grandfather was an idealist, an old maniac; at sixty years of age, to attempt to overturn my constitution and to replace it by one of his! An economist, indeed! A man who dreams financial schemes and could hardly perform the duties of a village tax-gatherer decently! Robespierre and Danton have done less harm to France than M. Necker. Your grandfather is the cause of the saturnalia which have desolated France. Upon his head be all the blood of the Revolution!" "Sire, I trust that posterity will speak more favorably of him. During his administration, he was compared with Sully and Colbert, and I trust to the justice of posterity." "Posterity will perhaps not speak of him at all," returned Napoleon.

"You are young, M. de Staël," he added, changing his tone, and taking the petitioner familiarly by the ear. "Your frankness pleases me: I like to see a son plead the cause of his mother. She confided to you a difficult mission, and you have discharged it with intelligence. I cannot give you false hopes, so I do not conceal from you that you will obtain nothing whatever. I'll have none of your mother in the city where I dwell. Women should knit stockings, and not talk politics." As Napoleon rode away from Chambéry, he said to Duroc, "Was I not rather hard with that young man? After all, I am glad of it. The thing is settled once for all. France is no place for the family of Necker."[8]

During the absence of Madame de Staël in Germany, her father died, and she hastened to return to Coppet. She collected and published his writings, and appended to them a biographical memoir. She cherished his memory with a passion bordering on monomania, which led her, whenever she saw an old man in affliction, to seek to alleviate his sorrows. She often said, upon hearing good news, "I owe this to the intercessions of my father."

She found it difficult satisfactorily to occupy her leisure. She used to say that she would prefer living on two thousand francs a year in the Rue Jean Pain Mollet at Paris, to spending one hundred thousand at Geneva. But she made no effort to obtain a recall, at least by imposing restraint upon her tongue. Knowing that she was surrounded by spies, and that her bitter allusions to Napoleon were reported at the Tuileries, she continued to exhaust her wit upon the acts of his government, and upon the tyranny of him whom she called "Robespierre on horseback."

Amateur theatricals, upon a diminutive stage built for the purpose, afforded some amusement to the exile of Coppet. The audiences were principally French residents at Geneva, whose ambition to be able to boast of their admission into Madame de Staël's intimacy, induced them to travel the wearisome road which separated the two places. While waiting for the lamps to be lighted, they ate bread and chocolate in the dark—this being the traditional lunch that a Frenchman carries in his pocket. On one occasion, the performance was Racine's tragedy of Andromaque. Madame de Staël played Hermione effectively, it would seem, but with a redundancy of gesture that somewhat marred the illusion. Madame Récamier acted Andromaque, the interesting widow; but the critics were so absorbed in the contemplation of her wondrous beauty that they have left little record of her histrionic ability. The characters of Oreste, Pylade and Pyrrhus were performed by M. de Labéboyère, Benjamin Constant and Sismondi, the historian. The two latter were very amusing, it appears, though the play being a tragedy, mirth could hardly have been the effect they desired to produce. Benjamin Constant, whose gestures were very broad and sweeping, once carried away a Grecian temple with the palm of his hand; Sismondi gave infinite zest to the representation by the purity of his Genevese accent. The prompter was M. Schlegel, the poet, critic and historian. His strong German pronunciation rendered him at best an inefficient assistant, for the actor, whose memory was treacherous, often failed to recognize the missing line, in the husky and guttural suggestions of the author of "Lucinde."

The health of Madame de Staël was now declining, and in order to recruit it she undertook a journey through Italy. On her return, she published "Corinne," a poetic description of the peninsula, in the form of a novel. Though deficient in construction and dramatic power, it possesses the highest merit as a work delineating character and descriptive of scenery, and inculcates a pure morality. Incident and plot form its least attractive features; its eloquent rhapsodies upon love, religion, virtue, nature, history and poetry, have given it an enduring place in literature. She now took up her abode at the required distance from Paris, at Chaumont-sur-Loire, where she inhabited the chateau already famous as the residence of Diane de Poitiers, Catherine de Medicis, and Nostradamus the soothsayer, and at this time in the possession of one of her most attached friends. She here wrote and prepared for the press a work on the habits, character and literature of the Germans. The manuscript was laid before the censors at Paris, who expunged certain passages, and then authorized its publication. This was in 1810.

Ten thousand copies had been already printed, when the whole edition was seized at the publishers', by gendarmes sent by Savary, the minister of police. Madame de Staël was ordered to quit France in eight days. She withdrew again to Coppet, from whence she opened a correspondence with Savary upon this arbitrary, and indeed illegal, proceeding. She had been given to understand that the motive for the suppression was her omission to mention the name of Napoleon in connection with Germany, where his armies had lately made him conspicuous. She wrote to Savary that she did not see how she could have introduced the Emperor and his "soldiery" into a purely literary work. To this Savary replied that she was misinformed upon the motive which had actuated him, and that her exile was the natural consequence of her conduct for years past. "We are not so reduced in France," he added, "as to seek for models among the nations which you admire. Your book is not French, and the air of France does not suit you." This impertinent letter was prefixed to the first edition of "Germany" published in London, in 1813.

During her residence at Coppet, Madame de Staël, now a widow and forty-two years of age, became acquainted with M. de Rocca, a French officer. She felt an interest in him even before she saw him, for he was said to be young, noble and brave; what was a still more attractive feature, he was wounded and an invalid. They first met in a public ball-room. She was dressed, it appears, in a gaudy and unbecoming style, and was followed from point to point by a train of admirers and flatterers. "Is that the famous woman?" said de Rocca. "She is very plain, and I abhor such continual aiming at effect." She spoke to him, expressed sympathy for his condition, and speedily effected a complete revolution in his opinions. From a caviller he became an admirer, and from an admirer a suitor. They were privately married, and the secret was carefully kept until the reading of her will, after her death, for she felt that the match was an ill-assorted one, and could hardly fail to excite ridicule. Besides, she was unwilling to change her name, "as it belonged to Europe," to quote her own words to De Rocca.

The tyranny to which she was subjected at the period of this marriage, by Napoleon, became annoying and perplexing. She was not only exiled from France, but warned not to go further than six miles from Coppet. Mathieu de Montmorency was exiled for visiting her, as was also Madame Récamier, as has already been narrated. M. Schlegel, who aided her in the education of her three children, was compelled to leave her. She was seized with the gloomiest apprehensions, and resolved to escape from the sphere of Napoleon's power. The prefect of Geneva was instructed, from Paris, to suggest to Madame de Staël a means of recovering the sovereign's good graces—the publication of some loyal stanzas upon the birth of Napoleon's heir. "Tell those that sent you," she replied, "that I have no wishes in connection with the King of Rome, except the desire that his mother get him a healthy wet-nurse."

She now passed her time in studying the map of Europe, in choosing an asylum, and in devising a route by which to get to it. She at last departed for England, which she approached through Russia and Sweden. Once beyond French influence, she was treated with the highest consideration and the warmest cordiality. Among the distinguished men admitted to her intimacy, Lord Byron held the first place, and she often gave him advice both upon his conduct and his verse. It was now that she published her "Germany," She had the deep satisfaction of seeing her reputation as a critic and delineator of national manners elevated by it to the highest point.

She welcomed with delight the overthrow and abdication of Napoleon, and at once returned to Paris, where she attached herself to the party advocating a representative government under Louis XVIII. The restored sovereign caused the royal treasury to pay to her family the two million francs due M. Necker at his retirement from office—a measure of justice to which Napoleon would never consent. During the Hundred Days she retired to Switzerland, totally weaned from all interest in public life. Her health began to fail, and she still further weakened it by the use of opium. She devoted herself closely to the composition of her last work, the "French Revolution," which now ranks as one of the most philosophical, though perhaps not the most impartial, histories of that period. Her sleepless nights she spent in prayer; she became gentle, patient and devout. "I think I know," she said, in her last moments, "what the passage from life to death is. I am convinced the goodness of God makes it easy; our thoughts become indistinct, and the pain is not great." She died with perfect composure, in 1817, in the fifty-first year of her age. Her husband, who was devotedly attached to her, survived her but a few months.

Madame de Staël was the most distinguished authoress of her time. As a woman, she was always independent and sincere, and her faults—vanity and an uncontrollable thirst for applause—may easily be pardoned in view of her many talents. Napoleon could have won her to his government at any moment, had he chosen to do so. It is perhaps fortunate for literature that she was compelled to live in isolation, as neither "Corinne" nor "Germany" would have been written had she been able to reside in Paris, instead of travelling to occupy her exile. It is a singular and not unfair commentary upon Napoleon's reign, that its most remarkable literary celebrity—in point of mere chronology—owed her supremacy to his persecution; and it is a permissible inference, that had his government preferred to foster and cherish her genius, Madame de Staël would have been known to posterity as little more than a precocious child, a brilliant conversationalist, an unsexed woman, and a factious politician.

[1] Mém. de Madame de Genlis, 92.

[2] Soc. Franç. sous le Directoire, 298.

[3] Napoléon et ses Contemporains, i. 229.

[4] Lac. Rév. Française, ii. 140.

[5] Vide "Delphine," vol. ii. 386.

[6] Ducrest, Mém. de Joséphine, 23.

[7] It is from a copy of this portrait, by Gérard, in the Historical Gallery of Versailles, that the most accurate likenesses of Madame de Staël are taken.

[8] Bour. viii. 101.

In the year 1794, Oswald, Lord Nevil, a Scotch nobleman, left Edinburgh to pass the winter in Italy.[1] He possessed a noble and handsome person, a fine mind, a great name, an independent fortune; but his health was impaired; and the physicians, fearing that his lungs were affected, prescribed the air of the south. He followed their advice, though with little interest in his own recovery, hoping, at least, to find some amusement in the varied objects he was about to behold. The heaviest of all afflictions, the loss of a father, was the cause of his malady. The remorse inspired by scrupulous delicacy still more embittered his regret, and haunted his imagination. Such sufferings we readily convince ourselves that we deserve, for violent griefs extend their influence even over the realms of conscience. At five-and-twenty he was tired of life; he judged the future by the past, and no longer relished the illusions of the heart. No one could be more devoted to the service of his friends; yet not even the good he effected gave him one sensation of pleasure. He constantly sacrificed his tastes to those of others; but this generosity alone, far from proving a total forgetfulness of self, may often be attributed to a degree of melancholy, which renders a man careless of his own doom. The indifferent considered this mood extremely graceful; but those who loved him felt that he employed himself for the happiness of others, like a man who hoped for none; and they almost repined at receiving felicity from one on whom they could never bestow it. His natural disposition was versatile, sensitive, and impassioned; uniting all the qualities which could excite himself or others; but misfortune and repentance had rendered him timid, and he thought to disarm, by exacting nothing from fate. He trusted to find, in a firm adherence to his duties, and a renouncement of all enjoyments, a security against the sorrows which had distracted him. Nothing in the world seemed worth the risk of these pangs; but while we are still capable of feeling them, to what kind of life can we fly for shelter?

Lord Nevil flattered himself that he should quit Scotland without regret, as he had remained there without pleasure; but the dangerous dreams of imaginative minds are not thus fulfilled; he was sensible of the ties which bound him to the scene of his miseries, the home of his father. There were rooms he could not approach without a shudder, and yet, when he had resolved to fly them, he felt more alone than ever. A barren dearth seized on his heart; he could no longer weep; no more recall those little local associations which had so deeply melted him; his recollections had less of life; they belonged not to the things that surrounded him. He did not think the less of those he mourned, but it became more difficult to conjure back their presence. Sometimes, too, he reproached himself for abandoning the place where his father had dwelt. "Who knows," would he sigh, "if the shades of the dead follow the objects of their affection? They may not be permitted to wander beyond the spots where their ashes repose! Perhaps, at this moment, is my father deploring my absence, powerless to recall me. Alas! may not a host of wild events have persuaded him that I have betrayed his tenderness, turned rebel to my country, to his will, and all that is sacred on earth?"

These remembrances occasioned him such insupportable despair, that, far from daring to confide them to any one, he dreaded to sound their depths himself; so easy is it, out of our own reflections, to create irreparable evils!

It costs added pain to leave one's country, when one must cross the sea. There is such solemnity in a pilgrimage, the first steps of which are on the ocean. It seems as if a gulf were opening behind you, and your return becoming impossible; besides, the sight of the main always profoundly impresses us, as the image of that infinitude which perpetually attracts the soul, and in which thought ever feels herself lost. Oswald, leaning near the helm, his eyes fixed on the waves, appeared perfectly calm. Pride and diffidence generally prevented his betraying his emotions even before his friends; but sad feelings struggled within. He thought on the time when that spectacle animated his youth with a desire to buffet the tides, and measure his strength with theirs.

"Why," he bitterly mused, "why thus constantly yield to meditation? There is such rapture in active life! in those violent exercises that make us feel the energy of existence! then death itself may appear glorious; at least it is sudden, and not preceded by decay; but that death which finds us without being bravely sought—that gloomy death which steals from you, in a night, all you held dear, which mocks your regrets, repulses your embrace, and pitilessly opposes to your desire the eternal laws of time and nature—that death inspires a kind of contempt for human destiny, for the powerlessness of grief, and all the vain efforts that wreck themselves against necessity."

Such were the torturing sentiments which characterized the wretchedness of his state. The vivacity of youth was united with the thoughts of another age; such as might well have occupied the mind of his father in his last hours; but Oswald tinted the melancholy contemplations of age with the ardor of five-and-twenty. He was weary of everything; yet, nevertheless, lamented his lost content, as if its visions still lingered.

This inconsistency, entirely at variance with the will of nature (which has placed the conclusion and the gradation of things in their rightful course), disordered the depths of his soul; but his manners were ever sweet and harmonious; nay, his grief, far from injuring his temper, taught him a still greater degree of consideration and gentleness for others.

Twice or thrice in the voyage from Harwich to Emden the sea threatened stormily. Nevil directed the sailors, reassured the passengers; and while, toiling himself, he for a moment took the pilot's place, there was a vigour and address in what he did, which could not be regarded as the simple effect of personal strength and activity, for mind pervaded it all.

When they were about to part, all on board crowded round him to take leave, thanking him for a thousand good offices, which he had forgotten: sometimes it was a child that he had nursed so long; more frequently, some old man whose steps he had supported while the wind rocked the vessel. Such an absence of personal feeling was scarcely ever known. His voyage had passed without his having devoted a moment to himself; he gave up his time to others, in melancholy benevolence. And now the whole crew cried, with one voice, "God bless you, my Lord! we wish you better."

Yet Oswald had not once complained; and the persons of a higher class, who had crossed with him, said not a word on this subject; but the common people, in whom their superiors rarely confide, are wont to detect the truth without the aid of words; they pity you when you suffer, though ignorant of the cause; and their spontaneous sympathy is unmixed with either censure or advice.

[1] Neither of these names is Scotch. We are not informed whether the hero's Christian name is Oswald, or Nevil his family one, as well as his title. He signs the former to his letters, and constantly calls himself an Englishman.—TRANSLATOR.

Travelling, say what we will, is one of the saddest pleasures in life. If you ever feel at ease in a strange place, it is because you have begun to make it your home; but to traverse unknown lands, to hear a language which you hardly comprehend, to look on faces unconnected with either your past or future, this is solitude without repose or dignity; for the hurry to arrive where no one awaits you, that agitation whose sole cause is curiosity, lessens you in your own esteem, while, ere new objects can become old, they have bound you by some sweet links of sentiment and habit.

Oswald felt his despondency redoubled in crossing Germany to reach Italy, obliged by war to avoid France and its frontiers, as well as the troops, who rendered the roads impassable. This necessity for attending to detail, and taking, almost every instant, a new resolution, was utterly insufferable. His health, instead of improving, often obliged him to stop, while he longed to arrive at some other place, or at least to fly from where he was. He took the least possible care of his constitution; accusing himself as culpable, with but too great severity. If he wished still to live, it was but for the defence of his country.

"My native land," would he sigh—"has it not a parental right over me? but I want power to serve it usefully. I must not offer it the feeble existence which I drag towards the sun, to beg of him some principle of life, that may struggle against my woes. None but a father could receive me thus, and love me the more, the more I was deserted by nature and by fate."

He had flattered himself that a continual change of external objects would somewhat divert his fancy from its usual routine; but he could not, at first, realize this effect. It were better, after any great loss, to familiarize ourselves afresh with all that had surrounded us, accustom ourselves to the old familiar faces, to the house in which we had lived, and the daily duties which we ought to resume; each of these efforts jars fearfully on the heart; but nothing multiplies them like an absence.

Oswald's only pleasure was exploring the Tyrol, on a horse which he had brought from Scotland, and who climbed the hills at a gallop. The astonished peasants began by shrieking with fright, as they saw him borne along the precipice's edge, and ended by chapping their hands in admiration of his dexterity grace, and courage. He loved the sense of danger. It reconciled him for the instant with that life which he thus seemed to regain, and which it would have been easy to lose.

At Inspruck, where he stayed for some time, in the house of a banker, Oswald was much interested by the history of Count d'Erfeuil, a French emigrant, who had sustained the total loss of an immense fortune with perfect serenity. By his musical talents he had maintained himself and an aged uncle, over whom he watched till the good man's death, constantly refusing the pecuniary aid which had been pressed on him. He had displayed the most brilliant valor—that of France—during the war, and an unchangeable gayety in the midst of reverses. He was anxious to visit Rome, that he might find a relative, whose heir he expected to become; and wished for a companion, or rather a friend, with whom to make the journey agreeably.

Lord Nevil's saddest recollections were attached to France; yet he was exempt from the prejudices which divided the two nations. One Frenchman had been his intimate friend, in whom he had found a union of the most estimable qualities. He therefore offered, through the narrator of Count d'Erfeuil's story, to take this noble and unfortunate young man with him to Italy. The banker in an hour informed him that his proposal was gratefully accepted. Oswald rejoiced in rendering this service to another, though it cost him much to resign his seclusion; and his reserve suffered greatly at the prospect of finding himself thus thrown on the society of a man he did not know.

He shortly received a visit of thanks from the Count, who possessed an elegant manner, ready politeness, and good taste; from the first appearing perfectly at his ease. Every one, on seeing him, wondered at what he had undergone; for he bore his lot with a courage approaching to forgetfulness. There was a liveliness in his conversation truly admirable, while he spoke of his own misfortunes; though less so, it must be owned, when extended to other subjects.

"I am greatly obliged to your Lordship," said he, "for transporting me from Germany, of which I am tired to death."—"And yet," replied Nevil, "you are universally beloved and respected here."—"I have friends, indeed, whom I shall sincerely regret; for in this country one meets none but the best of people; only I don't know a word of German; and you will confess that it were a long and tedious task to learn it. Since I had the ill-luck to lose my uncle, I have not known what to do with my leisure; while I had to attend on him, that filled up my time; but now the four-and-twenty hours hang heavily on my hands."—"The delicacy of your conduct towards your kinsman, Count," said Nevil, "has impressed me with the deepest regard for you."—"I did no more than my duty. Poor man! he had lavished his favors on my childhood. I could never have left him, had he lived to be a hundred; but 'tis well for him that he's gone; 'twere well for me to be with him," he added, laughing, "for I've little to hope in this world. I did my best, during the war, to get killed; but since fate would spare me, I must live on as I may."—"I shall congratulate myself on coming hither," answered Nevil, "should you do well in Rome; and if——"—"Oh, Heaven!" interrupted d'Erfeuil, "I do well enough everywhere; while we are young and cheerful, all things find their level. 'Tis neither from books nor from meditation that I have acquired my philosophy, but from being used to the world and its mishaps; nay, you see, my Lord, I have some reason for trusting to chance, since I owe to it the opportunity of travelling with you." The Count then agreed on the hour for setting forth next day, and, with a graceful bow, departed. After the mere interchange of civilities with which their journey commenced, Oswald remained silent for some hours; but perceiving that this fatigued his fellow-traveller, he asked him if he anticipated much pleasure in their Italian tour. "Oh," replied the Count, "I know what to expect, and don't look forward to the least amusement. A friend of mine passed six months there, and tells me that there is not a French province without a better theatre, and more agreeable society than Rome; but in that ancient capital of the world I shall be sure to find some of my countrymen to chat with; and that is all I require."—"Then you have not been tempted to learn Italian?"—"No, that was never included in the plan of my studies," he answered, with so serious an air, that one might have thought him expressing a resolution founded on the gravest motives. "The fact is," he continued, "that I like no people but the English and the French. Men must be proud, like you, or wits, like ourselves; all the rest is mere imitation." Oswald said nothing. A few moments afterwards the Count renewed the conversation by sallies of vivacity and humor, in which he played on words most ingeniously; but neither what he saw or what he felt was his theme. His discourse sprang not from within, nor from without; but, steering clear alike of reflection and imagination, found its subjects in the superficial traits of society. He named twenty persons in France and England, inquiring if Lord Nevil knew them; and relating as many pointed anecdotes, as if, in his opinion, the only language for a man of taste was the gossip of good company. Nevil pondered for some time on this singular combination of courage and frivolity, this contempt of misfortune, which would have been so heroic if it had cost more effort, instead of springing from the same source which rendered him incapable of deep affections. "An Englishman," thought he, "would have been overwhelmed by similar circumstances. Whence does this Frenchman derive his fortitude, yet pliancy of character? Does he rightly understand the art of living? I deem myself his superior, yet am I not ill and wretched? Does his trifling course accord better than mine with the fleetness of life? Must one fly from thought as from a foe, instead of yielding all the soul to its power?" In vain he thought to clear these doubts; he could call no aid from his own intellectual region, whose best qualities were even more ungovernable than its defects.

The Count gave none of his attention to Italy, and rendered it almost impossible for Oswald to be entertained by it. D'Erfeuil turned from his friend's admiration of a fine country, and sense of its picturesque charm; our invalid listened as oft as he could to the sound of the winds, or the murmur of the waves; the voice of nature did more for his mind than sketches of coteries held at the foot of the Alps, among ruins, or on the banks of the sea. His own grief would have been less an obstacle to the pleasure he might have tasted than was the mirth of d'Erfeuil. The regrets of a feeling heart may harmonize with a contemplation of nature and an enjoyment of the fine arts; but frivolity, under whatever form it appears, deprives attention of its power, thought of its originality, and sentiment of its depth. One strange effect of the Count's levity, was its inspiring Nevil with diffidence in all their affairs together.

The most reasoning characters are often the easiest abashed. The giddy embarrass and overawe the contemplative; and the being who calls himself happy appears wiser than he who suffers. D'Erfeuil was every way mild, obliging, and free; serious only in his self-love, and worthy to be liked as much as he could like another; that is, as a good companion in pleasure and in peril, but one who knew not how to participate in pain. He wearied of Oswald's melancholy; and, as well from the goodness of his heart as from taste, he strove to dissipate it. "What would you have?" he often said. "Are you not young, rich, and well, if you choose? you are but fancy-sick. I have lost all, and know not what will become of me; yet I enjoy life as if I possessed every earthly blessing."—"Your courage is as rare as it is honorable," replied Nevil; "but the reverses you have known wound less than do the sorrows of the heart."—"The sorrows of the heart! ay, true, they must be the worst of all; but still you must console yourself; for a sensible man ought to banish from his mind whatever can be of no service to himself or others. Are we not placed here below to be useful first, and consequently happy? My dear Nevil, let us hold by that faith."

All this was rational enough, in the usual sense of the word; for d'Erfeuil was, in most respects, a clear-headed man. The impassioned are far more liable to weakness, than the fickle; but, instead of his mode of thinking securing the confidence of Nevil, he would fain have assured the Count that he was the happiest of human beings, to escape the infliction of his attempts at comfort. Nevertheless, d'Erfeuil became strongly attached to Lord Nevil. His resignation and simplicity, his modesty and pride, created respect irresistibly. The Count was perplexed by Oswald's external composure, and taxed his memory for all the grave maxims, which in childhood he had heard from his old relations, in order to try their effect upon his friend; and, astonished at failing to vanquish his apparent coldness, he asked himself, "Am I not good-natured, frank, brave, and popular in society? What do I want, then, to make an impression on this man? May there not be some misunderstanding between us, arising, perhaps, from his not sufficiently understanding French?"

An unforeseen circumstance much increased the sensations of deference which d'Erfeuil felt towards his travelling companion. Lord Nevil's state of health obliged him to stop some days at Ancona. Mount and main conspired to beautify its site; and the crowd of Greeks, orientally seated at work before the shops, the varied costumes of the Levant, to be met with in the streets, give the town an original and interesting air. Civilization tends to render all men alike, in appearance if not in reality; yet fancy may find pleasure in characteristic national distinctions.

Men only resemble each other when sophisticated by sordid or fashionable life; whatever is natural admits of variety. There is a slight gratification, at least for the eyes, in that diversity of dress, which seems to promise us experience in equally novel ways of feeling and of judgement. The Greek, Catholic, and Jewish forms of worship exist peaceably together in Ancona. Their ceremonies are strongly contrasted; but the same sigh of distress, the same petition for support, ascends to Heaven from all.

The Catholic church stands on a height that overlooks the main, the lash of whose tides frequently blends with the chant of the priests. Within, the edifice is loaded by ornaments of indifferent taste; but, pausing beneath the portico, the soul delights to recall its purest of emotions—religion—while gazing at that superb spectacle, the sea, on which man never left his trace. He may plough the earth, and cut his way through mountains, or contract rivers into canals, for the transport of his merchandise; but if his fleets for a moment furrow the ocean, its waves as instantly efface this slight mark of servitude, and it again appears such as it was on the first day of its creation.[1]

Lord Nevil had decided to start for Rome on the morrow, when he heard, during the night, a terrific cry from the streets, and hastening from his hotel to learn the cause, beheld a conflagration which, beginning at the port, spread from house to house towards the top of the town. The flames were reflected afar off in the sea; the wind, increasing their violence, agitated their images on the waves, which mirrored in a thousand shapes the blood-red features of a lurid fire. The inhabitants, having no engine in good repair,[2] hurriedly bore forth what succor they could; above their shouts was heard a clank of chains, as the slaves from the galleys toiled to save the city which served them for a prison. The various people of the Levant, whom commerce had drawn to Ancona, betrayed their dread by the stupor of their looks. The merchants, at sight of their blazing stores, lost all presence of mind. Trembling for fortune as much as for life, the generality of men were scared from that zealous enthusiasm which suggests resources in emergency.

The shouts of sailors have ever something dreary in their sound; fear now rendered them still more appalling. The mariners of the Adriatic were clad in peculiar red and brown hoods, from which peeped their animated Italian faces, under every expression of dismay. The natives, lying on the earth, covered their heads with their cloaks, as if nothing remained for them to do but to exclude the sight of their calamity. Reckless fury and blind submission reigned alternately, but no one evinced that coolness which redoubles our means and our strength.

Oswald remembered that there were two English vessels in the harbor; the pumps of both were in perfect order; he ran to the Captain's house, and put off with him in a boat, to fetch them. Those who witnessed this exclaimed to him, "Ah, you foreigners do well to leave our unhappy town!"—"We shall soon return," said Oswald. They did not believe him, till he came back, and placed one of the pumps in front of the house nearest to the port, the other before that which blazed in the centre of the street. Count d'Erfeuil exposed his life with gay and careless daring. The English sailors and Lord Nevil's servants came to his aid, for the populace remained motionless, scarcely understanding what these strangers meant to do, and without the slightest faith in their success. The bells rung from all sides; the priests formed processions; weeping females threw themselves before their sculptured saints; but no one thought on the natural powers which God has given man for his own defence. Nevertheless, when they perceived the fortunate effects of Oswald's activity—the flames extinguished, and their homes preserved—rapture succeeded astonishment; they pressed around him, and kissed his hand with such ardent eagerness, that he was obliged by feigned displeasure to drive them from him, lest they should impede the rapid succession of necessary orders for saving the town. Every one ranked himself beneath Oswald's command; for, in trivial as in great events, where danger is, firmness will find its rightful station; and while men strongly fear, they cease to feel jealousy. Amid the general tumult, Nevil now distinguished shrieks more horrible than aught he had previously heard, as if from the other extremity of the town. He inquired their source; and was told that they proceeded from the Jews' quarter. The officer of police was accustomed to close its gates every evening; the fire gained on it, and the occupants could not escape. Oswald shuddered at the thought, and bade them instantly open the barriers; but the women, who heard him, flung themselves at his feet, exclaiming, "Oh, our good angel! you must be aware that it is certainly on their account we have endured this visitation; it is they who bring us ill fortune; and if you set them free, all the water of the ocean will never quench these flames." They entreated him to let the Jews be burnt with as much persuasive eloquence as if they had been petitioning for an act of mercy. Not that they were by nature cruel, but that their superstitious fancies were forcibly struck by a great disaster. Oswald with difficulty contained his indignation at hearing a prayer so revolting. He sent four English sailors, with hatchets, to cut down the gate which confined these helpless men, who instantly spread themselves about the town, rushing to their merchandise, through the flames, with that greediness of wealth, which impresses us so painfully, when it drives men to brave even death; as if human beings, in the present state of society, had nothing to do with the simple gift of life. There was now but one house, at the upper part of the town, where the fire mocked all efforts to subdue it. So little interest had been shown in this abode, that the sailors, believing it vacant, had carried their pumps towards the port. Oswald himself, stunned by the calls for aid around him, had almost disregarded it. The conflagration had not been early communicated to this place, but it had made great progress there. He demanded so earnestly what the dwelling was, that at last a man informed him—the hospital for maniacs! Overwhelmed by these tidings, he looked in vain for his assistants, or Count d'Erfeuil; as vainly did he call on the inhabitants; they were employed in taking care of their property, and deemed it ridiculous to risk their lives for the sake of men who were all incurably mad. "It will be no one's fault if they die, but a blessing to themselves and families," was the general opinion; but while they expressed it, Oswald strode rapidly towards the building, and even those who blamed involuntarily followed him. On reaching the house, he saw, at the only window not surrounded by flame, the unconscious creatures, looking on, with that heart-rending laughter which proves either an ignorance of all life's sad realities, or such deep-seated despair as disarms death's most frightful aspect of its power. An indefinite chill seized him at this sight. In the severest period of his own distress he had felt as if his reason were deserting him; and, since then, never looked on insanity without the most painful sympathy. He secured a ladder which he found near, placed it against the wall, ascended through the flames, and entered by its window, the room where the unfortunate lunatics were assembled. Their derangement was sufficiently harmless to justify their freedom within doors; only one was chained. Fortunately the floor was not consumed, and Oswald's appearance in the midst of these degraded beings had all the effect of enchantment; at first, they obeyed him without resistance. He bade them descend before him, one after the other, by the ladder, which might in a few seconds be destroyed. The first of them complied in silence, so entirely had Oswald's looks and tones subdued him. Another, heedless of the danger in which the least delay must involve Oswald and himself, was inclined to rebel; the people, alive to all the horrors of the situation, called on Lord Nevil to come down, and leave the senseless wretches to escape as they could; but their deliverer would listen to nothing that could defeat his generous enterprise. Of the six patients found in the hospital, five were already safe. The only one remaining was the youth who had been fettered to the wall. Oswald loosened his irons, and bade him take the same course as his companions; but, on feeling himself at liberty, after two years of bondage, he sprung about the room with frantic delight, which, however, gave place to fury, when Oswald desired him to get out of the window. But finding persuasion fruitless, and seeing that the fatal element was fast extending its ravages, he clasped the struggling maniac in his arms; and, while the smoke prevented his seeing where to step, leaped from the last bars of the ladder, giving the rescued man, who still contended with his benefactor, into the hands of persons whom he charged to guard him carefully.

Oswald, with his locks disordered, and his countenance sweetly, yet proudly animated by the perils he had braved, struck the gazing crowd with an almost fanatical admiration; the women, particularly, expressed themselves in that fanciful language, the universal gift of Italy, which often lends a dignity to the address of her humblest children. They cast themselves on their knees before him, crying—"Assuredly, thou art St. Michael, the patron of Ancona. Show us thy wings, yet do not fly, save to the top of our cathedral, where all may see and pray to thee!"—"My child is ill; oh, cure him!" said one.—"Where," added another, "is my husband, who has been absent so many years? tell me!" Oswald was longing to escape, when d'Erfeuil, joining him, pressed his hand. "Dear Nevil!" he began, "could you share nothing with your friend? 'twas cruel to keep all the glory to yourself."—"Help me from this place!" returned Oswald, in a low voice. A moment's darkness favoured their flight, and both hastened in search of post-horses. Sweet as was the first sense of the good he had just effected, with whom could he partake it, now that his best friend was no more? So wretched is the orphan that felicity and care alike remind him of his heart's solitude. What substitute has life for the affection born with us? for that mental intercourse, that kindred sympathy, that friendship, formed by Heaven to exist but between parent and child? We may love again; but the happiness of confiding the whole soul to another—that we can never regain.

[1] Lord Byron translated this paragraph in the fourth canto of Childe Harold, but without acknowledging whence the ideas were borrowed:—

"Roll on, thou deep and dark blue ocean—roll!

Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain;

Man marks the earth with ruin—his control

Stops with the shore;—upon the wat'ry plain

The wrecks are all thy deed, nor doth remain

A shadow of man's ravage. * *

* * * * *

Time writes no wrinkle on thine azure brow—

Such as creation's dawn beheld, thou rollest now."

Such as creation's dawn beheld, thou rollest now."

See stanzas 179 and 182.—TR.

[2] Ancona is not much better supplied to this day.

Oswald sped to Rome, over the marches of Ancona, and the Papal State, without remarking or interesting himself in anything. Besides its melancholy, his disposition had a natural indolence, from which it could only be roused by some strong passion. His taste was not yet developed; he had lived but in England and France;[1] in the latter, society is everything; in the former, political interests nearly absorb all others. His mind, concentrated in his griefs, could not yet solace itself in the wonders of nature, or the works of art.

D'Erfeuil, running through every town, with the Guide-Book in his hand, had the double pleasure of making away with his time, and of assuring himself that there was nothing to see worthy the praise of any one who had been in France. This nil admirari of his discouraged Oswald, who was also somewhat prepossessed against Italy and Italians. He could not yet penetrate the mystery of the people or their country—a mystery that must be solved rather by imagination than by that spirit of judgment which an English education particularly matures.

The Italians are more remarkable for what they have been, and might be, than for what they are. The wastes that surround Rome, as if the earth, fatigued by glory, disdained to become productive, are but uncultivated and neglected lands to the utilitarian. Oswald, accustomed from his childhood to a love of order and public prosperity, received, at first, an unfavorable impression in crossing such abandoned plains as approaches to the former queen of cities. Looking on it with the eye of an enlightened patriot, he censured the idle inhabitants and their rulers.

The Count d'Erfeuil regarded it as a man of the world; and thus the one from reason, and the other from levity, remained dead to the effect which the Campagna produces on a mind filled by a regretful memory of those natural beauties and splendid misfortunes, which invest this country with an indescribable charm. The Count uttered the most comic lamentations over the environs of Rome. "What!" said he, "no villas? no equipages? nothing to announce the neighborhood of a great city? Good God, how dull!" The same pride with which the natives of the coast had pointed out the sea, and the Neapolitans showed their Vesuvius, now transported the postilions, who exclaimed, "Look! that is the cupola of St. Peter's."—"One might take it for the dome of the Invalides!" cried d'Erfeuil. This comparison, rather national than just, destroyed the sensation which Oswald might have received, in first beholding that magnificent wonder of man's creation.

They entered Rome, neither on a fair day, nor a lovely night, but on a dark and misty evening, which dimmed and confused every object before them. They crossed the Tiber without observing it; passed through the Porto del Popolo, which led them at once to the Corso, the largest street of modern Rome, but that which possesses the least originality of feature, as being the one which most resembles those of other European towns.

The streets were crowded; puppet-shows and mountebanks formed groups round the base of Antoninus's pillar. Oswald's attention was caught by these objects, and the name of Rome forgotten. He felt that deep isolation which presses on the heart, when we enter a foreign scene, and look on a multitude to whom our existence is unknown, and who have not one interest in common with us. These reflections, so saddening to all men, are doubly so to the English, who are accustomed to live among themselves, and find it difficult to blend with the manners of other lands. In Rome, that vast caravansary, all is foreign, even the Romans, who seem to live there, not like its possessors, but like pilgrims who repose among its ruins.[2] Oppressed by laboring thoughts, Oswald shut himself in his room, instead of exploring the city; little dreaming that the country he had entered beneath such a sense of dejection would soon become the mine of so many new ideas and enjoyments.

[1] This alludes to a previous tour; in his present one, Oswald has not approached France. His longest stay was in Germany.—TR.

[2] This observation is made in a letter on Rome, by M. Humboldt, brother to the celebrated traveller, and Prussian minister at Rome; a gentleman whose writings and conversation alike do honor to his learning and originality.

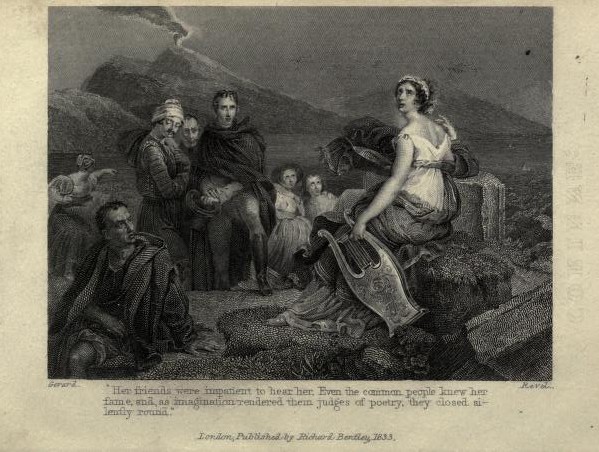

Oswald awoke in Rome. The dazzling sun of Italy met his first gaze, and his soul was penetrated with sensations of love and gratitude for that heaven, which seemed to smile on him in these glorious beams. He heard the bells of numerous churches ringing, discharges of cannon from various distances, as if announcing some high solemnity. He inquired the cause, and was informed that the most celebrated female was about that morning to be crowned at the capitol—Corinne, the poet and improvisatrice, one of the loveliest women of Rome. He asked some questions respecting this ceremony, hallowed by the names of Petrarch and of Tasso; every reply he received warmly excited his curiosity.

There can be nothing more hostile to the habits and opinions of an Englishman, than any great publicity given to the career of a woman. But the enthusiasm with which all imaginative talents inspire the Italians, infects, at least for the time, even strangers, who forget prejudice itself among people so lively in the expression of their sentiments.

The common populace of Rome discuss their statues, pictures, monuments, and antiquities, with much taste; and literary merit, carried to a certain height, becomes with them a national interest.

On going forth into the public resorts, Oswald found that the streets, through which Corinne was to pass, had been adorned for her reception. The herd, who generally throng but the path of fortune or of power, were almost in a tumult of eagerness to look on one whose soul was her only distinction. In the present state of the Italians, the glory of the fine arts is all their fate allows them; and they appreciate genius of that order with a vivacity which might raise up a host of great men, if applause could suffice to produce them—if a hardy life, strong interest, and an independent station were not the food required to nourish thought.

Oswald walked the streets of Rome, awaiting the arrival of Corinne; he heard her named every instant; every one related, some new trait, proving that she united all the talents most captivating to the fancy. One asserted that her voice was the most touching in Italy; another, that, in tragic acting, she had no peer; a third, that she danced like a nymph, and drew with equal grace and invention—all said that no one had ever written or extemporized verses so sweet, and that, in daily conversation, she displayed alternately an ease and an eloquence which fascinated all who heard her. They disputed as to which part of Italy had given her birth; some earnestly contending that she must be a Roman, or she could not speak the language with such purity. Her family name was unknown. Her first work, which had appeared five years since, bore but that of Corinne. No one could tell where she had lived, nor what she had been before that period; and she was now nearly six-and-twenty. Such mystery and publicity, united in the fate of a female of whom every one spoke, yet whose real name no one knew, appeared, to Nevil as among the wonders of the land he came to see. He would have judged such a woman very severely in England; but he applied not her social etiquettes to Italy; and the crowning of Corinne awoke in his breast the same sensation which he would have felt on reading an adventure of Ariosto's.

A burst of exquisite melody preceded the approach of the triumphal procession. How thrilling is each event that is heralded by music! A great number of Roman nobles, and not a few foreigners, came first. "Behold her retinue of admirers!" said one.—"Yes," replied another; "she receives a whole world's homage, but accords her preference to none. She is rich, independent; it is even believed, from her noble air, that she is a lady of high birth, who wishes to remain unknown."—"A divinity veiled in clouds," concluded a third. Oswald looked on the man who spoke thus; everything betokened him a person of the humblest class; but the natives of the South converse as naturally in poetic phrases, as if they imbibed them with the air, or were inspired by the sun.

At last four spotless steeds appeared in the midst of the crowd drawing an antiquely-shaped car, besides which walked a maiden band in snowy vestments. Wherever Corinne passed, perfumes were thrown upon the air; the windows, decked with flowers and scarlet hangings, were peopled by gazers, who shouted, "Long live Corinne! Glory to beauty and to genius!"

This emotion was general; but, to partake it, one must lay aside English reserve and French raillery; Nevil could not yield to the spirit of the scene, till he beheld Corinne.