By WILLIAM CARUTHERS

A Personal Narrative of People and Places

COPYRIGHT 1951 BY WILLIAM CARUTHERS

Printed in the U.S.A. by P-B Press, Inc., Pomona, Calif.

Published by Death Valley Publishing Co.

Ontario, California

To one who, without complaint or previous experience with desert hardships, shared with me the difficult and often dangerous adventures in part recorded in this book, which but for her persistent urging, would never have reached the printed page. She is, of course, my wife—with me in a sense far broader than the words imply: always—always.

This book is a personal narrative of people and places in Panamint Valley, the Amargosa Desert, and the Big Sink at the bottom of America. Most of the places which excited a gold-crazed world in the early part of the century are now no more, or are going back to sage. Of the actors who made the history of the period, few remain.

It was the writer’s good fortune that many of these men were his friends. Some were or would become tycoons of mining or industry. Some would lucklessly follow jackasses all their lives, to find no gold but perhaps a finer treasure—a rainbow in the sky that would never fade.

It is the romance, the comedy, the often stark tragedy these men left along the trail which you will find in the pages that follow.

Necessarily the history of the region, often dull, is given first because it gives a clearer picture of the background and second, because that history is little known, being buried in the generally unread diaries of John C. Fremont, Kit Carson, Lt. Brewerton, Jedediah Smith, and the stories of early Mormon explorers.

It is interesting to note that a map popular with adventurers of Fremont’s time could list only six states west of the Mississippi River. These were Texas, Indian Territory, Missouri, Oregon, and Mexico’s two possessions—New Mexico and Upper California. There was no Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, Washington, or either of the Dakotas. No Kansas. No Nebraska.

Sources of material are given in the text and though careful research was made, it should be understood that the history of Death Valley country is argumentative and bold indeed is one who says, “Here are the facts.”

With something more than mere formality, the writer wishes to thank those mentioned below:

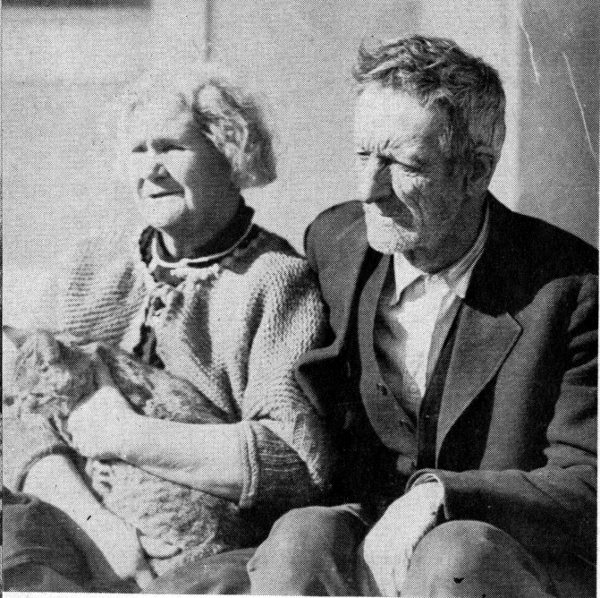

My longtime friend, Senator Charles Brown of Shoshone who has often given valuable time to make available research material which otherwise would have been almost impossible to obtain. Of more value, 10 have been his personal recollections of Greenwater, Goldfield, and Tonopah, in all of which places he had lived in their hectic days.

Mrs. Charles Brown, daughter of the noted pioneer, Ralph Jacobus (Dad) Fairbanks and her sister, Mrs. Bettie Lisle, of Baker, California. The voluminous scrapbooks of both, including one of their mother, Celestia Abigail Fairbanks, all containing information of priceless value were always at my disposal while preparing the manuscript.

Dad Fairbanks, innumerable times my host, was a walking encyclopedia of men and events.

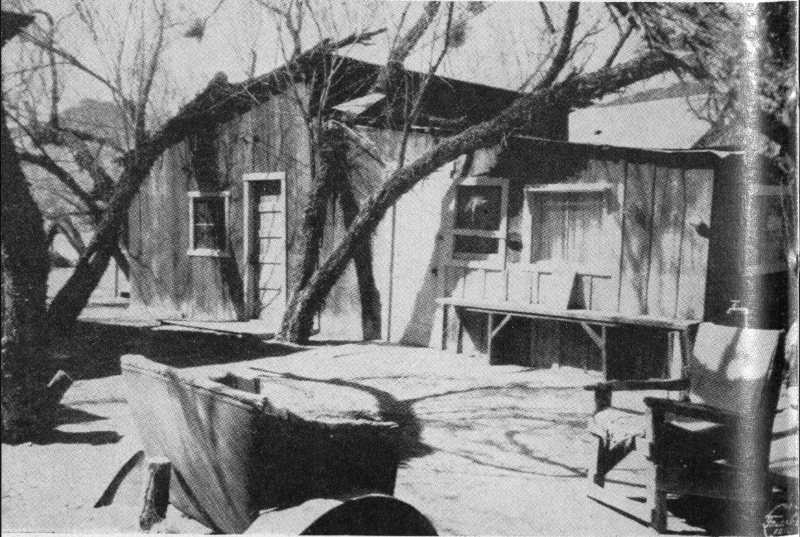

One depository of source material deserves special mention. Nailed to the wall of Shorty Harris’ Ballarat cabin was a box two feet wide, four feet long, with four shelves. The box served as a cupboard and its calico curtains operated on a drawstring. On the top shelf, Shorty would toss any letter, clipping, record of mine production, map, or bulletin that the mails had brought, visitors had given, or friends had sent. And there they gathered the dust of years.

Wishing to locate the address of Peter B. Kyne, author of The Parson of Panamint, whose host Shorty had been, I removed these documents and discovered that the catch-all shelf was a veritable treasure of little-known facts about the Panamint of earlier days.

There were maps, reports of geologic surveys, and bulletins now out of print; newspapers of the early years and scores of letters with valuable material bearing the names of men internationally known.

It is with a sense of futility that I attempt to express my indebtedness to my wife, who with a patience I cannot comprehend, kept me searching for the facts whenever and wherever the facts were to be found; typing and re-typing the manuscript in its entirety many times to make it, if possible, a worthwhile book.

Ontario, California, December 22, 1950

In the newspaper office where the writer worked, was a constant parade of adventurers. Talented press agents; promoters; moguls of mining and prospectors who, having struck it rich, now lived grandly in palatial homes, luxurious hotels or impressive clubs. In their wake, of course, was an engaging breed of liars, and an occasional adventuress who by luck or love had left a boom town crib to live thereafter “in marble halls with vassals” at her command. All brought arresting yarns of Death Valley.

For 76 years this Big Sink at the bottom of America had been a land of mystery and romantic legend, but there had been little travel through it since the white man’s first crossing. “I would have starved to death on tourists’ trade,” said the pioneer Ralph (Dad) Fairbanks.

More than 3,000,000 people lived within a day’s journey in 1925, but excepting a few, who lived in bordering villages and settlements, those who had actually been in Death Valley could be counted on one’s fingers and toes. The reasons were practical. It was the hottest region in America, with few water holes and these far apart. There were no roads—only makeshift trails left by the wagons that had hauled borax in the Eighties. Now they were little more than twisting scars through brush, over dry washes and dunes, though listed on the maps as roads. For the novice it was a foolhardy gamble with death. “There are easier ways of committing suicide,” a seasoned desert man advised.

I had been up and down the world more perhaps than the average person and this seemed to be a challenge to one with a vagabond’s foot and a passion for remote places. So one day I set out for Death Valley.

At the last outpost of civilization, a two-cabin resort, the sign over a sand-blasted, false-fronted building stressed: “Free Information. Cabins. Eats. Gas. Oil. Refreshments.”

Needing all these items, I parked my car and walked into a foretaste of things-to-come. The owner, a big, genial fellow, was behind the counter using his teeth to remove the cork from a bottle labeled “Bourbon”—a task he deftly accomplished by twisting on the bottle instead of the cork. “I want a cabin for the night,” I told him, “and when you have time, all the free information I can get.”

“You’ve come to headquarters,” he beamed as he set the bottle on the table, glanced at me, then at the liquor and added: “Don’t know your drinking sentiments but if you’d like to wet your whistle, take one on the house.”

While he was getting glasses from a cabinet behind the counter, a slender, wiry man with baked skin, coal-black eyes and hair came through a rear door, removed a knapsack strapped across his shoulders and set it in the farthest corner of the room. Two or three books rolled out and were replaced only after he had wiped them carefully with a red bandana kerchief. A sweat-stained khaki shirt and faded blue overalls did not affect an impression he gave of some outstanding quality. It may have been the air of self assurance, the calm of his keen eyes or the majesty of his stride as he crossed the floor.

My host glanced at the newcomer and set another glass on the table, “You’re in luck,” he said to me. “Here comes a man who can tell you anything you want to know about this country.” A moment later the newcomer was introduced as “Blackie.”

“Whatever Blackie tells you is gospel. Knows every trail man or beast ever made in that hell-hole, from one end to the other. Ain’t that right, Blackie?”

Without answering, Blackie focused an eye on the bottle, picked it up, shook it, watched the beads a moment. “Bourbon hell ... just plain tongue oil.”

After the drink my host showed me to one of the cabins—a small, boxlike structure. Opening the door he waved me in. “One fellow said he couldn’t whip a cat in this cabin, but you haven’t got a cat.” He set my suitcase on a sagging bed, brought in a bucket of water, put a clean towel on the roller and wiped the dust from a water glass with two big fingers. “When you get settled come down and loaf with us. Just call me Bill. Calico Bill, I’m known as. Came up here from the Calico Mountains.”

“Just one question,” I said. “Don’t you get lonesome in all this desolation?”

“Lonesome? Mister, there’s something going on every minute. You’d be surprised. Like what happened this morning. Did you meet a truck on your way up, with a husky young driver and a girl in a skimpy dress?”

“Yes,” I said. “At a gas station a hundred miles back, and the girl was a breath-taker.”

“You can say that again,” Bill grinned. “Prettiest gal I ever saw—bar none. She’s just turned eighteen. Married to a fellow fifty-five if he’s a day. He owns a truck and hauls for a mine near here at so much a load. Jealous sort. Won’t let her out of his sight. You can’t blame a young fellow for looking at a pretty girl. But this brute is so crazy jealous he took to locking her up in his cabin while he was at work. Fact is, she’s a nice clean kid and if I’d known about it, I’d have chased him off. I reckon she was too ashamed to tell anybody.

“Of course the young fellows found it out and just to worry him, two or three of ’em came over here to play a prank on him and a hell of a prank it was. They made a lot of tracks around his cabin doors and windows. He saw the tracks and figured she’d been stepping out on him. So instead of locking her in as usual, he began to take her to work with him so he could keep his eyes on her.

“Yesterday it happened. His truck broke down and this morning he left early to get parts, but he was smart enough to take her shoes with him. Then he nailed the doors and windows from the outside. Soon as he was out of hearing, somehow she busted out and came down to my store barefooted and asked me if I knew of any way she could get a ride out. ‘I’m leaving, if I have to walk,’ she says. Then she told me her story. He’d bought her back in Oklahoma for $500. She is one of ten children. Her folks didn’t have enough to feed ’em all. This old guy, who lived in their neighborhood and had money, talked her parents into the deal. ‘I just couldn’t see my little sisters go hungry,’ she said, and like a fool she married him.

“I reckon the Lord was with her. We see about three outside trucks a year around here, but I’d no sooner fixed her up with a pair of shoes before one pulls up for gas. I asked the driver if he’d give her a ride to Barstow. He took just one look. ‘I sure will,’ he says and off they went.

“You see what I mean,” Bill said, concluding his story. “Things like that. Of course we don’t watch no parades but we also don’t get pushed around and run over and tromped on.”

In the last twelve words Bill expressed what hundreds have failed to explain in pages of flowered phrase—the appeal of the desert.

Soon I was back at the store. Bill and Blackie, over a new bottle were swapping memories of noted desert characters who had highlighted the towns and camps from Tonopah to the last hell-roarer. The 14 great, the humble, the odd and eccentric. Through their conversation ran such names as Fireball Fan; Mike Lane; Mother Featherlegs; Shorty Harris; Tiger Lil; Hungry Hattie; Cranky Casey; Johnny-Behind-the-Gun; Dad Fairbanks; Fraction Jack Stewart; the Indian, Hungry Bill; and innumerable Slims and Shortys featured in yarns of the wasteland.

Blackie’s chief interest in life, Bill told me was books. “About all he does is read. Doesn’t have to work. Of course, like everybody in this country, he’s always going to find $2,000,000,000 this week or next.”

Though only incidental, history was brought into their conversation when Bill, giving me “free information” as his sign announced, told me I would be able to see the place where Manly crossed the Panamint.

“Manly never knew where he crossed,” Blackie said. “He tried to tell about it 40 years afterward and all he did was to start an argument that’s going on yet. That’s why I say you can write the known facts about Death Valley history on a postage stamp with the end of your thumb.”

The tongue oil loosened Calico Bill’s story of Indian George and his trained mountain sheep. “George had the right idea about gold. Find it, then take it out as needed. One time an artist came to George’s ranch and made a picture of the ram. When he had finished it he stepped behind his easel and was watching George eat a raw gopher snake when the goat came up. Rams are jealous and mistaking the picture for a rival, he charged like a thunderbolt.

“It didn’t hurt the picture, but knocked the painter and George through both walls of George’s shanty. George picked himself up. ‘Heap good picture. Me want.’ The fellow gave it to him and for months George would tease that goat with the picture. One day he left it on a boulder while he went for his horse. When he got back, the boulder was split wide open and the picture was on top of a tree 50 feet away.

“Somebody told George about a steer in the Chicago packing house which led other steers to the slaughter pen and it gave George an idea. One day I found him and his goat in a Panamint canyon and asked why he brought the goat along. ‘Me broke. Need gold.’ Since he didn’t have pick, shovel, or dynamite, I asked how he expected to get gold.

“‘Pick, shovel heap work,’ George said. ‘Dynamite maybe kill. Sheep better. Me show you.’ He told me to move to a safe place and after scattering some grain around for the goat, George scaled the boulder. It was big as a house. A moment later I saw him unroll the picture and with strings attached, let it rest on one corner of the big rock. Then holding the strings, he disappeared into his blind higher up. Suddenly he made a hissing noise. The Big Horn stiffened, saw the picture, lowered his head and never in my life have I seen such a crash. Dust filled the air and fragments fell for 10 minutes. When I went over George was gathering 15 nuggets big as goose eggs. ‘White man heap dam’ fool,’ he grunted. ‘Wants too much gold all same time. Maybe lose. Maybe somebody steal. No can steal boulder.’”

The “tongue oil” had been disposed of when Blackie suggested that we step over to his place, a short distance around the point of a hill. “Plenty more there.”

Bill had told me that as a penniless youngster Blackie had walked up Odessa Canyon one afternoon. Within three days he was rated as a millionaire. Within three months he was broke again. Later Blackie told me, “That’s somebody’s dream. I got about $200,000 and decided I belonged up in the Big Banker group. They welcomed me and skinned me out of my money in no time.”

It was Blackie who proved to my satisfaction that money has only a minor relation to happiness. His house was part dobe, part white tufa blocks. On his table was a student’s lamp, a pipe, and can of tobacco. A book held open by a hand axe. Other books were shelved along the wall. He had an incongruous walnut cabinet with leaded glass doors. Inside, a well-filled decanter and a dozen whiskey glasses and a pleasant aroma of bourbon came from a keg covered with a gunny sack and set on a stool in the corner.

“This country’s hard on the throat,” he explained.

Blackie’s kingdom seemed to have extended from the morning star to the setting sun. He had been in the Yukon, in New Zealand, South Africa, and the Argentine. Gold, hemp, sugar, and ships had tossed fortunes at him which were promptly lost or spent.

For a man who had found compensation for such luck, there is no defeat. Certainly his philosophy seemed to meet his needs and that is the function of philosophy.

It was cool in the late evening and he made a fire, chucked one end of an eight-foot log into the stove and put a chair under the protruding end. Bill asked why he didn’t cut the log. “Listen,” Blackie said, “you’re one of 100 million reasons why this country is misgoverned. Why should I sweat over that log when a fire will do the job?... That book? Just some fellow’s plan for a perfect world. I hope I’ll not be around when they have it.

“The town of Calico? It was a live one. When John McBryde and Lowery Silver discovered the white metal there, a lot of us desert rats got in the big money. In the first seven years of the Eighties it was bonanza and in the eighth the town was dead.”

But the stories of fortunes made in Mule and Odessa Canyons were of less importance to him than a habit of the town judge. “Chewed tobacco all the time and swallowed the juice, ‘If a fellow’s guts can’t 16 stand it,’ he would say, ‘he ought to quit,’ and he’d clap a fine on anybody who spat in his court.

“Never knew Jack Dent, did you? Englishman. Now there was a drinking man. Said his only ambition was to die drunk. One pay day he got so cockeyed he couldn’t stand, so his pals laid him on a pool table and went on with their drinking. Every time they ordered, Jack hollered for his and somebody would take it over and pour it down him. ‘Keep ’em comin’,’ he says. ‘If I doze off, just pry my jaws open and pour it down.’

“The boys took him at his word. Every time they drank, they took a drink to Jack. When the last round came they took Jack a big one. They tried to pry his lips open but the lips didn’t give. Jack Dent’s funeral was the biggest ever held in the town.

“Bill was telling you I made a million there, and every now and then I hear of somebody telling somebody else I made a million in Africa. And another in the Yukon. The truth is, what little I’ve got came out of a hole in a whiskey barrel instead of a mine shaft.

“A few years back a strike was made down in the Avawatz that started a baby gold rush. I joined it. A fellow named Gypsum came in with a barrel of whiskey, thinking there’d be a town, but it didn’t turn out that way. Gypsum had no trouble disposing of his liquor and stayed around to do a little prospecting. One day when I was starting for Johannesburg, he asked me to deliver a message to a bartender there. Gypsum had a meat cleaver in his hand and was sharpening it on a butcher’s steel to cut up a mountain sheep he’d killed.

“‘Just ask for Klondike and tell him to send my stuff. He’ll understand. Tell him if he doesn’t send it, I’m coming after it.’

“I didn’t know at the time that Gypsum had killed three men in honest combat and that one of them had been dispatched with a meat cleaver.

“I delivered the message verbatim. Klondike looked a bit worried. ‘What’s Gypsum doing?’ he asked. ‘When I left,’ I said, ‘he was sharpening a meat cleaver.’ Klondike turned white. ‘I’ll have it ready before you go.’

“When I called later, he told me he’d put Gypsum’s stuff in the back of my car. When I got back to camp and Gypsum came to my tent to ask about it, I told him to get it out of the car, which was parked a few feet away. Gypsum went for it and in a moment I heard him cussing. I looked out and he was trying to shoulder a heavy sack. Before I could get out to help him, the sack got away from him and burst at his feet. The ground was covered with nickles, dimes, quarters, halves. ‘There’s another sack.’ Gypsum said. ‘The son of a bitch has sent me $2500 in chicken feed. Just for spite.’

“Because it was a nuisance, Gypsum loaned it to the fellows about, all of whom were his friends. They didn’t want it but took it just to accommodate Gypsum. There was nothing to spend it for. Somebody started a poker game and I let ’em use my tent because it was the largest. I rigged up a table by sawing Gypsum’s whiskey barrel in two and nailing planks over the open end. Every night after supper they started playing. I furnished light and likker and usually I set out grub. It didn’t cost much but somebody suggested that in order to reimburse me, two bits should be taken out of every jackpot. A hole was slit in the top. It was a fast game and the stakes high. It ran for weeks every evening and the Saturday night session ended Monday morning.

“Of course some were soon broke and they began to borrow from one another. Finally everybody was broke and all the money was in my kitty. I took the top off the barrel and loaned it to the players, taking I.O.U.’s, I had to take the top off a dozen times and when it was finally decided there was no pay dirt in the Avawatz, I had a sack full of I.O.U.’s.

“Once I tried to figure out how many times that $2500 was loaned, but I gave up. I learned though, why these bankers pick up a pencil and start figuring the minute you start talking. They are on the right end of the pencil.”

Early the next morning while Bill was servicing my car for the trip ahead, with some tactful mention of handy gadgets he had for sale, we noticed Blackie coming with a man who ran largely to whiskers. “That’s old Cloudburst Pete,” Bill told me. “Another old timer who has shuffled all over this country.”

“How did he get that moniker?” I asked.

“One time Pete came in here and was telling us fellows about a narrow escape he had from a cloudburst over in the Panamint. Pete said the cloud was just above him and about to burst and would have filled the canyon with a wall of water 90 feet high. A city fellow who had stopped for gas, asked Pete how come he didn’t get drowned. Pete took a notion the fellow was trying to razz him. ‘Well, Mister, if you must know, I lassoed the cloud, ground-hitched it and let it bust....’”

After greeting Pete, Bill asked if he’d been walking all night.

“Naw,” Pete said. “Started around 11 o’clock, I reckon. Not so bad before sunup. Be hell going back. But I didn’t come here to growl about the weather. I want some powder so I can get started. Found color yesterday. Looks like I’m in the big money.”

“Fine,” Bill said. “I heard you’ve been laid up.”

“Oh, I broke a leg awhile back. Fell in a mine shaft. Didn’t amount to much.”

“I know about that, but didn’t you get hurt in a blast since then?”

“Oh that—yeh. Got blowed out of a 20-foot hole. Three-four ribs busted, the doc said. Come to think of it, believe he mentioned a fractured collar bone. Wasn’t half as bad as last week.”

“Good Lord ... what happened last week?”

“That crazy Cyclone Thompson. You know him ... he pulled a stope gate and let five-six tons of muck down on me. Nobody knew it—not even Cyclone. Wore my fingers to the bone scratching out. Look at these hands....”

Pete held up his mutilated hands. “They’ll heal but bigod—that pair of brand new double-stitched overalls won’t.”

“Well,” Bill chuckled, “you know where the powder is. Go in and get it.”

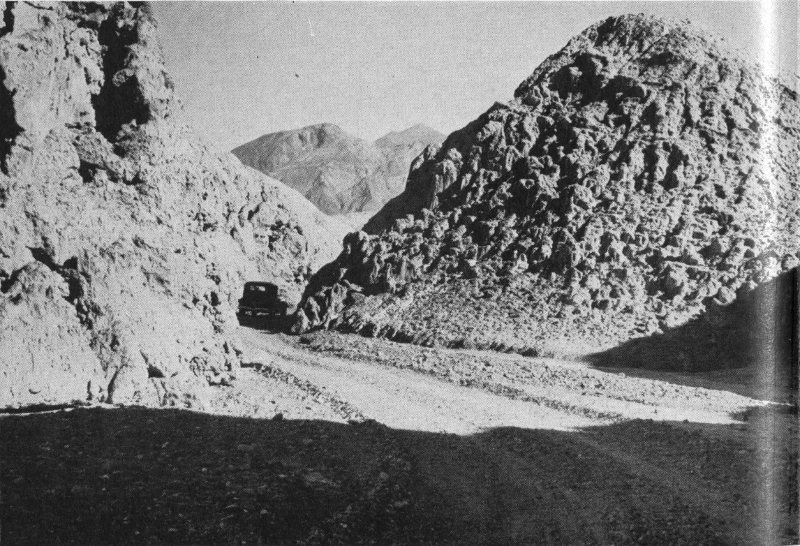

Bill and Blackie remained to see me off, each with a friendly word of advice. “Just follow the wheel tracks,” Bill said, as I climbed into my car and Blackie added: “Keep your eyes peeled for the cracker box signs along the edge of the road. You’ll see ’em nailed to a stake and stuck in the ground.”

A moment later I was headed into a silence broken only by the whip of sage against the car. Ahead was the glimmer of a dry lake and in the distance a great mass of jumbled mountains that notched the pale skies. Beyond—what?

I never dreamed then that for twenty-five years I would be poking around in those deceiving hills.

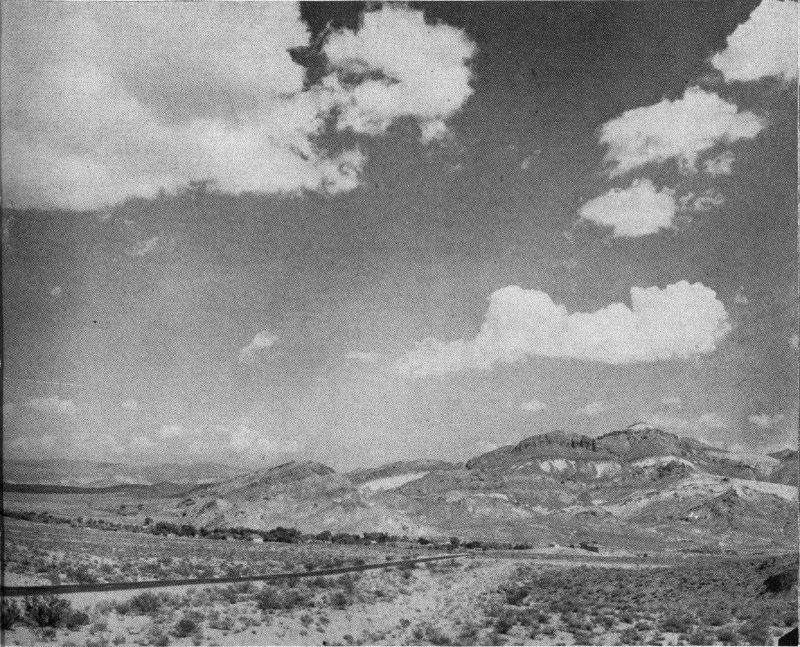

When you travel through the desolation of Death Valley along the Funeral Range, you may find it difficult to believe that several thousand feet above the top of your car was once a cool, inviting land with rivers and forests and lakes, and that hundreds of feet below you are the dry beds of seas that washed its shores.

Scientists assert that all life—both animal and vegetable began in these buried seas—probably two and one-half billion years ago.

It is certain that no life could have existed on the thin crust of earth covered as it was with deadly gases. Therefore, your remotest ancestors must have been sea creatures until they crawled out or were washed ashore in one of Nature’s convulsions to become land dwellers.

Since sea water contains more gold than has ever been found on the earth, it may be said that man on his way up from the lowest form of life was born in a solution of gold.

That he survived, is due to two urges—the sex urge and the urge for food. Without either all life would cease.

Note. The author’s book, Life’s Grand Stairway soon to be published, contains a fast moving, factual story of man and his eternal quest for gold from the beginning of recorded time.

Camping one night at Mesquite Spring, I heard a prospector cursing his burro. It wasn’t a casual cursing, but a classic revelation of one who knew burros—the soul of them, from inquisitive eyes to deadly heels. A moment later he was feeding lumps of sugar to the beast and the feud ended on a pleasant note.

We were sitting around the camp fire later when the prospector showed me a piece of quartz that glittered at twenty feet.

“Do you have much?” I asked.

“I’ve got more than Carter had oats, and I’m pulling out at daylight. Me and Thieving Jack.”

“I suppose,” I said aimlessly, “you’ll retire to a life of luxury; have a palace, a housekeeper, and a French chef.”

“Nope. Chinaman cook. Friend of mine struck it rich. He had a female cook. After that he couldn’t call his soul his own. Me? First money I spend goes for pie. Never had my fill of pie. Next—” He paused and looked affectionately at Thieving Jack. “I’m going to buy a ranch over at Lone Pine with a stream running smack through the middle. Snow water. I aim to build a fence head high all around it and pension that burro off. As for me—no mansion. Just a cottage with a screen porch all around. I’m sick of horseflies and mosquitoes.”

He was off at sunrise and my thought was that God went with him and Thieving Jack.

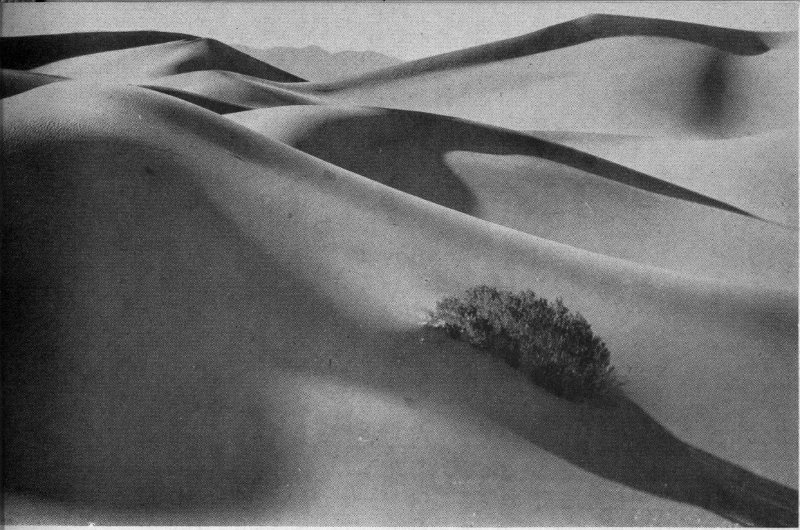

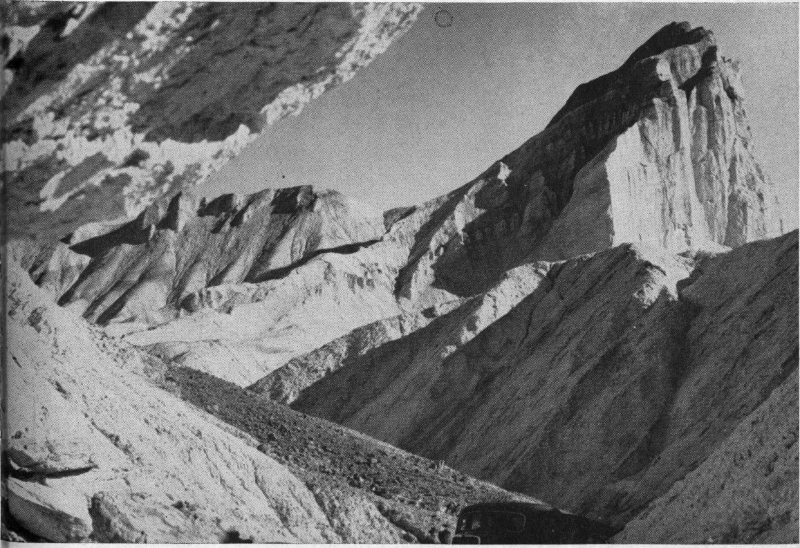

If you encounter scorching heat you will find little comfort in the fact that icebergs once floated in those ancient seas. It is almost certain that you will be curious about the disorderly jumble of gutted hills; the colorful canyons and strange formations and ask yourself what caused it.

The answer is found on Black Mountain in the Funeral Range. Here occurred a convulsion of nature without any known parallel and the tops of nearby mountains became the bottom of America—an upheaval so violent that the oldest rocks were squeezed under pressure from the nethermost stratum of the earth to lie alongside the youngest on the surface.

The seas and the fish vanished. The forests were buried. The prehistoric animals, the dinosaurs and elephants were trapped.

The result, after undetermined ages, is today’s Death Valley. A shorter explanation was that of my companion on my first trip to Black Mountain—a noted desert character—Jackass Slim. There we found a scientist who wished to enlighten us. To his conversation sprinkled with such words as Paleozoic and pre-Cambrian Slim listened raptly for an hour. Then the learned man asked Slim if he had made it plain.

“Sure,” Slim said. “You’ve been trying to say hell broke loose.”

The Indians, who saw Death Valley first, called it “Tomesha,” which means Ground Afire, and warned adventurers, explorers, and trappers that it was a vast sunken region, intolerant of life.

The first white Americans known to have seen it, belonged to the party of explorers led by John C. Fremont and guided by Kit Carson.

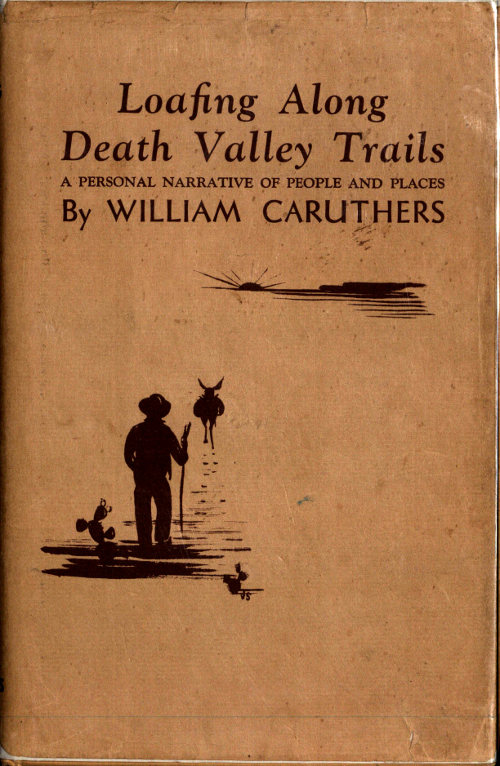

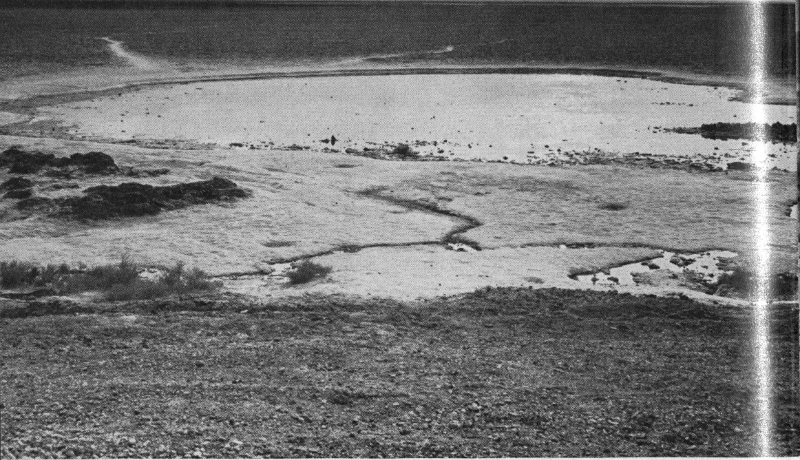

Death Valley ends on the south in the narrow opening between the terminus of the Panamint Range and that of the Black Mountains. Through this opening, though unaware of it, Fremont saw the dry stream bed of the Amargosa River, on April 27, 1844, flowing north and in the 21 distance “a high, snowy mountain.” This mountain was Telescope Peak, 11,045 feet high.

Nearly six years later, impatient Forty Niners enroute to California gold fields, having heard that the shortest way was through this forbidden sink, demanded that their guide take them across it.

“I will go to hell with you, but not through Death Valley,” said the wise Mormon guide, Captain Jefferson Hunt.

Scoffing Hunt’s warning, the Bennett-Arcane party deserted and with the Jayhawkers became the first white Americans to cross Death Valley. The suffering of the deserters, widely advertised, gave the region an evil reputation that kept it practically untraveled, unexplored, and accursed for the next 75 years, or until Charles Brown of Shoshone succeeded in having wheel tracks replaced with roads.

With the opening of the Eichbaum toll road from Lone Pine to Stovepipe Wells in 1926-7 a trickle of tourists began, but actually as late as 1932, Death Valley had fewer visitors than the Congo. A few prospectors, a few daring adventurers and a few ranchers had found in the areas adjoining, something in the great Wide Open that answered man’s inherent craving for freedom and peace. “The hills that shut this valley in,” explained the old timer, “also shut out the mess we left behind.”

Tales of treasure came in the wake of the Forty Niners but it was not until 1860 that the first prospecting party was organized by Dr. Darwin French at Oroville, California. In the fall of that year he set out to find the Lost Gunsight mine, the story of which is told in another chapter.

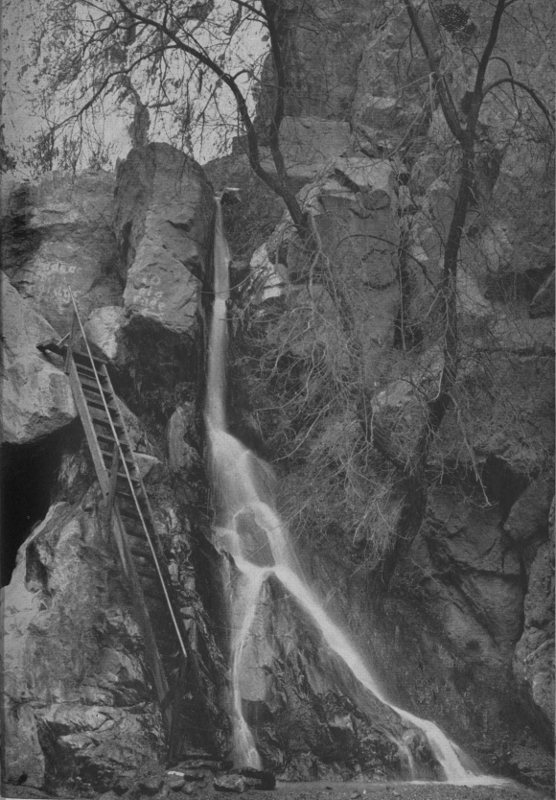

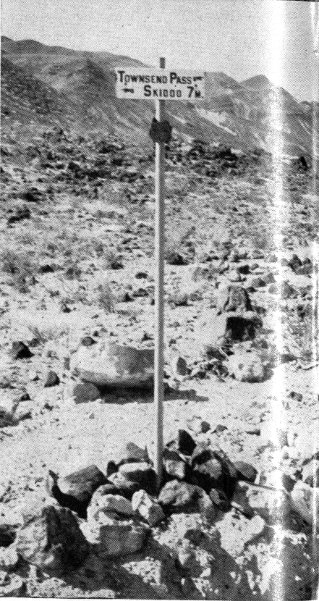

On this trip Dr. French discovered and gave his name to Darwin Falls and Darwin Wash in the Panamint range. He named Bennett’s Well on the floor of Death Valley to honor Asa (or Asabel) Bennett, a member of the Bennett-Arcane party. He gave the name of another member of that party to Towne’s Pass, now a thrilling route into Death Valley but then a breath-taking challenge to death.

He named Furnace Creek after finding there a crude furnace for reducing ore. He also named Panamint Valley and Panamint Range, but neither the origin of the word Panamint nor its significance is known. Indians found there said their tribe was called Panamint, but those around there are Shoshones and Piutes. (See note at end of this chapter.)

Also in 1860 William Lewis Manly who with John Rogers, a brave and husky Tennessean had rescued the survivors of the Bennett-Arcane party, returned to the valley he had named, to search for the Gunsight. Manly found nothing and reported later he was deserted by his companions and escaped death only when rescued by a wandering Indian.

In 1861 Lt. Ives on a surveying mission explored a part of the valley in connection with the California Boundary Commission. He used for pack animals some of the camels which had been provided by Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War, for transporting supplies across the western deserts.

In 1861 Dr. S. G. George, who had been a member of French’s party, organized one of his own and for the same reason—to find the Lost Gunsight. He made several locations of silver and gold, explored a portion of the Panamint Range. The first man ever to scale Telescope Peak was a member of the George party. He was W. T. Henderson, who had also been with Dr. French. Henderson named the mountain “because,” he said, “I could see for 200 miles in all directions as clearly as through a telescope.”

The most enduring accomplishment of the party was to bring back a name for the mountain range east of what is now known as Owens Valley, named for one of Fremont’s party of explorers. From an Indian chief they learned this range was called Inyo and meant “the home of a Great Spirit.” Ultimately the name was given to the county in the southeast corner of which is Death Valley.

Tragedy dogged all the early expeditions. July 21, 1871 the Wheeler expedition left Independence to explore Death Valley. This party of 60 included geologists, botanists, naturalists, and soldiers. One detachment was under command of Lt. George Wheeler. Lt. Lyle led the other. Lyle’s detachment was guided by C. F. R. Hahn and the third day out Hahn was sent ahead to locate water. John Koehler, a naturalist of the party is alleged to have said that he would kill Hahn if he didn’t find water. Failing to return Hahn was abandoned to his fate and he was never seen again.

William Eagan, guide of Wheeler’s party was sent to Rose Springs for water. He also failed to return. What became of him is not known and the army officers were justly denounced for callous indifference. On the desert, inexcusable desertion of a companion brands the deserter as an outcast and has often resulted in his lynching.

It is interesting to note that apart from a Government Land Survey in 1856, which proved to be utterly worthless, there is no authentic record of the white man in Death Valley between 1849 and 1860. However, during this decade the canyons on the west side of the Panamint harbored numerous renegades who had held up a Wells-Fargo stage or slit a miner’s throat for his poke of gold. Some were absorbed into the life of the wasteland when the discovery of silver in Surprise Canyon brought a hectic mob of adventurers to create hell-roaring Panamint City.

When, in the middle Seventies Nevada silver kings, John P. Jones and Wm. R. Stewart, who were Fortune’s children on the Comstock, decided $2,000,000 was enough to lose at Panamint City, many of the outlaws wandered over the mountain and down the canyon to cross Death Valley and settle wherever they thought they could survive on the eastern approaches.

Soon Ash Meadows, Furnace Creek Ranch, Stump Springs, the Manse Ranch, Resting Springs, and Pahrump Ranch became landmarks.

The first white man known to have settled in Death Valley was a person of some cunning and no conscience, known as Bellerin’ Teck, Bellowing Tex Bennett, and Bellowin’ Teck. He settled at Furnace Creek in 1870 and erected a shanty alongside the water where the Bennett-Arcane party had camped when driven from Ash Meadows by Indians whose gardens they had raided and whose squaws they had abused, according to a legend of the Indians and referred to with scant attention to details, by Manly. (Panamint Tom, famed Indian of the region, in speaking of this raid by the whites, told me that the head man of his tribe sent runners to Ash Meadows for reinforcements and that the recruits were marched in circles around boulders and in and out of ravines to give the impression of superior strength. This strategy deceived the whites, who then went on their way.)

Teck claimed title to all the country in sight. Little is known of his past, but whites later understood that he chose the forbidding region to outsmart a sheriff. He brought water through an open ditch from its source in the nearby foothills and grew alfalfa and grain. He named his place Greenland Ranch and it was the beginning of the present Furnace Creek Ranch.

There is a tradition that Teck supplemented his meager earnings from the ranch by selling half interests to wayfarers, subsequently driving them off.

There remains a record of one such victim—a Mormon adventurer named Jackson. In part payment Teck took a pair of oxen, Jackson’s money and his only weapon, a rifle. Shortly Teck began to show signs of dissatisfaction. His temper flared more frequently and Jackson became increasingly alarmed. When finally Teck came bellowing from his cabin, brandishing his gun, Jackson did the right thing at the right moment. He fled, glad to escape with his life.

This became the pattern for the next wayfarer and the next. Teck always craftily demanded their weapons in the trade, but knowing that sooner or later some would take their troubles to a sheriff or return for revenge, Teck sold the ranch, left the country and no trace of his destiny remains.

Before Aaron and Rosie Winters or Borax Smith ever saw Death Valley, one who was to attain fame greater than either listed more than 2000 different plants that grew in the area.

Notwithstanding this important contribution to knowledge of the valley’s flora, only one or two historians have mentioned his name, and these in books or periodicals long out of print.

Two decades later he was to become famous as Brigadier General Frederick Funston of the Spanish-American War—the only major war in America’s history fought by an army which was composed entirely of volunteers without a single draftee.

Of interest to this writer is the fact that he was my brigade commander and a soldier from the boots up. Not five feet tall, he was every inch a fighting man. I served with him while he captured Emilio Aguinaldo, famous Filipino Insurrecto.

While Bellerin’ Teck was selling half interests in the spectacular hills to the unwary, he actually walked over a treasure of more millions than his wildest dreams had conjured.

Teck’s nearest neighbor lived at Ash Meadows about 60 miles east of the valley.

Ash Meadows is a flat desert area in Nevada along the California border. With several water holes, subterranean streams, and abundant wild grass it was a resting place for early emigrants and a hole-in for prospectors. It was also an ideal refuge for gentlemen who liked its distance from sheriffs and the ease with which approaching horsemen could be seen from nearby hills.

Lacking was woman. The male needed the female but there wasn’t a white woman in the country. So he took what the market afforded—a squaw and not infrequently two or three. “He’s my son all right,” a patriarch once informed me, “but it’s been so long I don’t exactly recollect which of them squaws was his mother.”

Usually the wife was bought. Sometimes for a trinket. Often a horse. Among the trappers who first blazed the trails to the West, 30 beaver skins were considered a fair price for an able bodied squaw. She was capable in rendering domestic service and loyal in love. Too often the consort’s fidelity was transient.

“For 20 years,” said the noted trapper, Killbuck, “I packed a squaw along—not one, but a many. First I had a Blackfoot—the darndest slut as ever cried for fo-farrow. I lodge-poled her on Coulter’s Creek ... as good as four packs of beaver I gave for old Bull-tail’s daughter. He was the head chief of the Ricaree. Thar wan’t enough scarlet cloth nor beads ... in Sublette’s packs for her ... I sold her to Cross-Eagle for one of Jake Hawkins’ guns.... Then I tried the Sioux, the Shian 26 (Cheyenne) and a Digger from the other side, who made the best moccasins as ever I wore.”

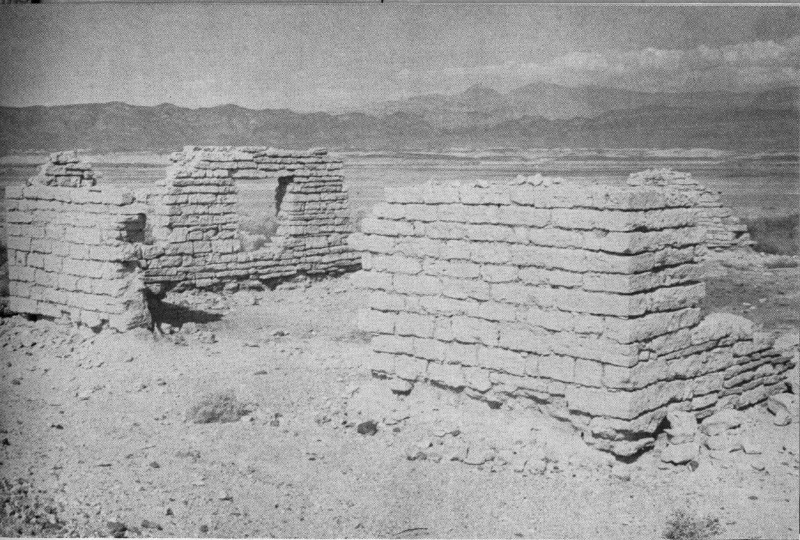

So Aaron Winters chose his mate from the available supply and with Rosie, part Mexican and Indian, part Spanish, he settled in Ash Meadows in a dugout. In front and adjoining had been added a shack, part wood, part stone. The floors were dirt. Rosie dragged in posts, poles, and brush and made a shed. Aaron found time between hunting and trapping to add a room of unmortared stone. At times there was no money, but piñon nuts grew in the mountains, desert tea and squaw cabbage were handy and the beans of mesquite could be ground into flour.

Rosie, to whom one must yield admiration, was not the first woman in Winters’ life. “He liked his women,” Ed Stiles recalled, “and changed ’em often.” But to Rosie, Aaron Winters was always devoted. Her material reward was little but all who knew her praised her beauty and her virtues.

One day when dusk was gathering there was a rap on the sagging slab door and Rosie Winters opened it on an angel unawares. The Winters invited the stranger in, shared their meager meal. After supper they sat up later than usual, listening to the story of the stranger’s travels. He was looking for borax, he told them. “It’s a white stuff....” At this time, only two or three unimportant deposits of borax were known to exist in America and the average prospector knew nothing about it.

The first borax was mined in Tibet. There in the form of tincal it was loaded on the backs of sheep, transported across the Himalayas and shipped to London. It was so rare that it was sold by the ounce. Later the more intelligent of the western prospectors began to learn that borax was something to keep in mind.

To Aaron Winters it was just something bought in a drug store, but Rosie was interested in the “white stuff.” She wanted to know how one could tell when the white stuff was borax. Patiently the guest explained how to make the tests: “Under the torch it will burn green....”

Finally Rosie made a bed for the wayfarer in the lean-to and long after he blew out his candle Rosie Winters lay awake, wondering about some white stuff she’d seen scattered over a flat down in the hellish heat of Death Valley. She remembered that it whitened the crust of a big area, stuck to her shoes and clothes and got in her hair when the wind lifted the silt.

The next morning Rosie and Aaron bade the guest good luck and goodbye and he went into the horizon without even leaving his name. Then Rosie turned to Aaron: “Maybe,” she said ... “maybe that 27 white stuff we see that time below Furnace Creek—maybe that is borax.”

“Might be,” Aaron answered.

“Why don’t we go see?” Rosie asked. “Maybe some Big Horn sheep—” Rosie knew her man and Aaron Winters got his rifle and Rosie packed the sow-belly and beans.

It was a long, gruelling trip down into the valley under a Death Valley sun but hope sustained them. They made their camp at Furnace Creek, then Rosie led Aaron over the flats she remembered. She scooped up some of the white stuff that looked like cotton balls while Aaron prepared for the test. Then the brief, uncertain moment when the white stuff touched the flame. Tensely they watched, Aaron grimly curious rather than hopeful; Rosie with pounding heart and lips whispering a prayer.

Then, miracle of miracles—the green flame. They looked excitedly into each other’s eyes, each unable to believe. In that moment, Rosie, always devout, lifted her eyes to heaven and thanked her God. Neither had any idea of the worth of their find. Vaguely they knew it meant spending money. A new what-not for Rosie’s mantel. Perhaps pine boards to cover the hovel’s dirt floor; maybe a few pieces of golden oak furniture; a rifle with greater range than Aaron’s old one; silk or satin to make a dress for Rosie.

“Writers have had to draw on their imagination for what happened,” a descendant of the Winters once told me. “They say Uncle Aaron exclaimed, ‘Rosie, she burns green!’ or ‘Rosie, we’re rich!’ but Aunt Rosie said they were so excited they couldn’t remember, but she knew what they did! They went over to the ditch that Bellerin’ Teck had dug to water the ranch and in its warm water soaked their bunioned feet.”

Returning to Ash Meadows they faced the problem of what to do with the “white stuff.” Unlike gold, it couldn’t be sold on sight, because it was a new industry, and little was known about its handling. Finally Aaron learned that a rich merchant in San Francisco, named Coleman was interested in borax in a small way and lost no time in sending samples to Coleman.

W. T. Coleman was a Kentucky aristocrat who had come to California during the gold rush and attained both fortune and the affection of the people of the state. He had been chosen leader of the famed Vigilantes, who had rescued San Francisco from a gang of the lawless as tough as the world ever saw.

Actually Coleman’s interest in borax was a minor incident in the handling of his large fortune and his passionate devotion to the development of his adopted state. For that reason alone, Coleman had become 28 interested in the small deposits of borax discovered by Francis Smith, first at Columbus Marsh.

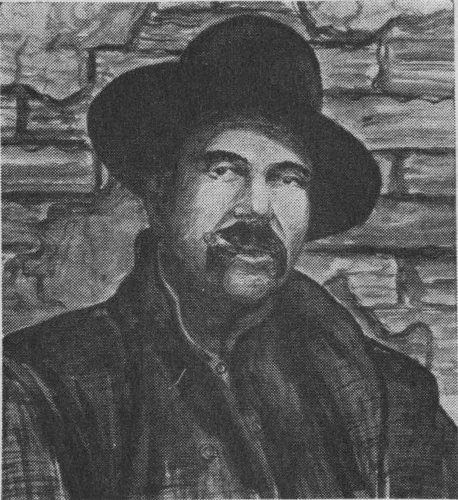

Smith had been a prospector before coming to California, wandering all over western country, looking for gold and silver. He was one of those who had heard that borax was worth keeping in mind.

Reaching Nevada and needing a grubstake, he began to cut wood to supply mines around Columbus, Aurora, and Candelaria. On Teel’s Marsh he found a large growth of mesquite, built a shack and claimed all the wood and the site as his own. Upon a portion of it, some Mexicans had cut and corded some of the wood and Smith refused to let them haul it off. They left grudgingly and with threats to return. The Mexicans, of course, had as much right to the wood as Smith.

Sensing trouble and having no weapons at his camp, he went twelve miles to borrow a rifle. But there were no cartridges and he had to ride sixty miles over the mountains to Aurora where he found only four. Returning to his shack, he found the Mexicans had also returned with reinforcements. Twenty-four were now at work and their mood was murderous. Smith had a companion whose courage he didn’t trust and ordered him to go out in the brush and keep out of the way.

The Mexicans told Smith they were going to take the wood. Smith warned that he would kill the first man who touched the pile. With only four cartridges to kill 20 men, it was obviously a bluff. One of the Mexicans went to the pile and picked up a stick. Smith put his rifle to his shoulder and ordered the fellow to drop it. Unafraid and still holding the stick the Mexican said: “You may kill me, but my friends will kill you. Put your rifle down and we will talk it over.”

They had cut additional wood during his absence and demanded that they be permitted to take all the wood they had cut. Smith consented and when the Mexicans had gone he staked out the marsh as a mining claim—which led to the connection with Coleman.

Upon receipt of Winters’ letter, Coleman forwarded it to Smith and asked him to investigate the Winters claim. Smith’s report was enthusiastic. Coleman then sent two capable men, William Robertson and Rudolph Neuenschwander to look over the Winters discovery, with credentials to buy. Again Rosie and Aaron Winters heard the flutter of angel wings at the hovel door. This time the angels left $20,000. Rarely in this world has buyer bought so much for so little, but to Aaron and Rosie Winters it was all the money in the world.

Despite the troubles of operating in a place so remote from market and with problems of a product about which too little was known, borax was soon adding $100,000 a year to Coleman’s already fabulous fortune.

Francis M. (Borax) Smith was put in charge of operations under the firm name of Coleman and Smith.

Freed from the sordid squalor of the Ash Meadows hovel, the Winters bought the Pahrump Ranch, a landmark of Pahrump Valley, and settled down to watch the world go by.

Thus began the Pacific Coast Borax Company, one of the world’s outstanding corporations. Later Smith was to become president of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and later still, he was to head a three hundred million dollar corporation for the development of the San Francisco and Oakland areas and then face bankruptcy and ruin.

Overlooking the site where Rosie and Aaron made the discovery, now stands the magnificent Furnace Creek Inn.

One day while sitting on the hotel terrace, I noticed a plane discharge a group of the Company’s English owners and their guests. Meticulously dressed, they paid scant attention to the desolation about and hastened to the cooling refuge of their caravansary. At dinner they sat down to buttered mignon and as they talked casually of the races at Ascot and the ball at Buckingham Palace, I looked out over that whitehot slab of hell and thought of Rosie and Aaron Winters trudging with calloused feet behind a burro—their dinner, sow-belly and beans.

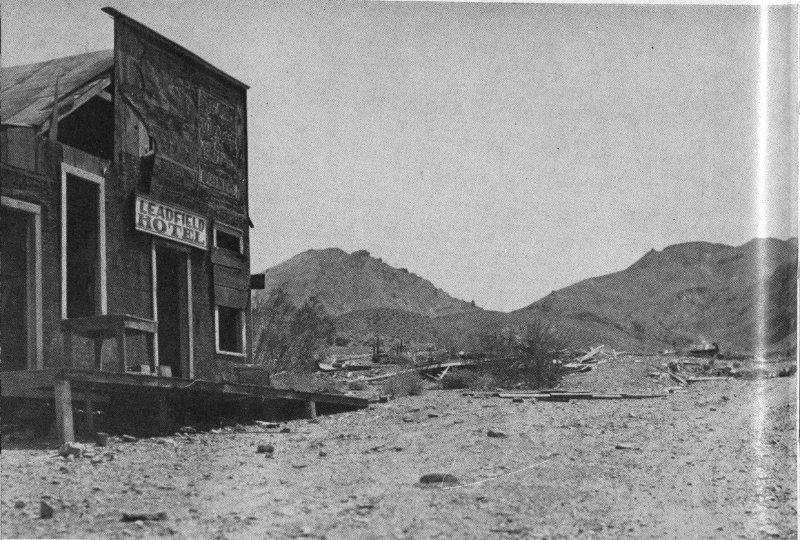

Actually the first discovery of borax in Death Valley was made by Isadore Daunet in 1875, five years before Winters’ discovery. Daunet had left Panamint City when it was apparent that town was through forever and with six of his friends was en route to new diggings in Arizona.

He was a seasoned, hardy adventurer and risked a short cut across Death Valley in mid-summer. Running out of water, his party killed a burro, drank its blood; but the deadly heat beat them down. Indians came across one of the thirst-crazed men and learned that Daunet and others were somewhere about. They found Daunet and two companions. The others perished.

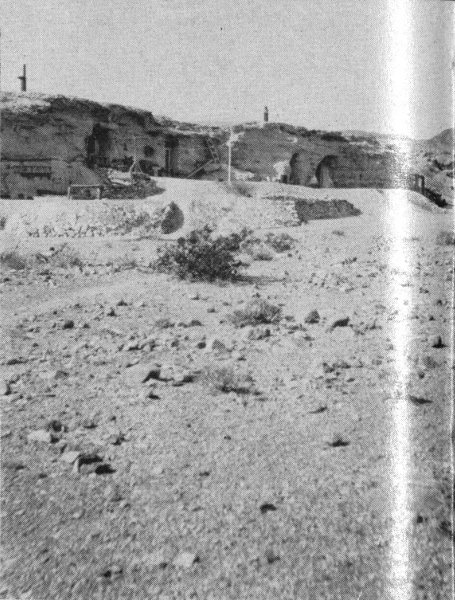

When Daunet heard of the Winters sale five years later, like Rosie Winters he remembered the white stuff about the water, to which the Indians had taken him. He hurried back and in 1880 filed upon mining claims amounting to 260 acres. He started at once a refining plant which he called Eagle Borax Works and began operating one year before Old Harmony began to boil borax in 1881. Daunet’s product however, was of inferior grade and unprofitable and work was soon abandoned. The unpredictable happened and dark days fell upon borax and William T. Coleman.

In 1888 the advocates of free trade had a field day when the bill authored by Roger Q. Mills of Texas became the law of the land and borax went on the free list. The empire of Coleman tumbled in a financial scare—attributed by Coleman to a banker who had falsely undervalued Coleman’s assets after a report by a borax expert who betrayed him. “My assets,” wrote Coleman, “were $4,400,000. My debts $2,000,000.” No person but Coleman lost a penny.

But Borax Smith was never one to surrender without a fight and 31 organized the Pacific Coast Borax Company to take over the property and the success of that company justifies the faith and the integrity of Coleman.

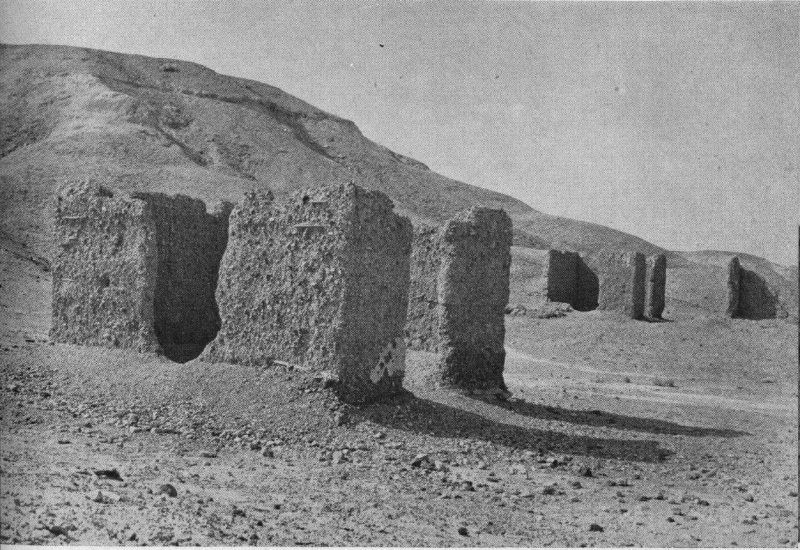

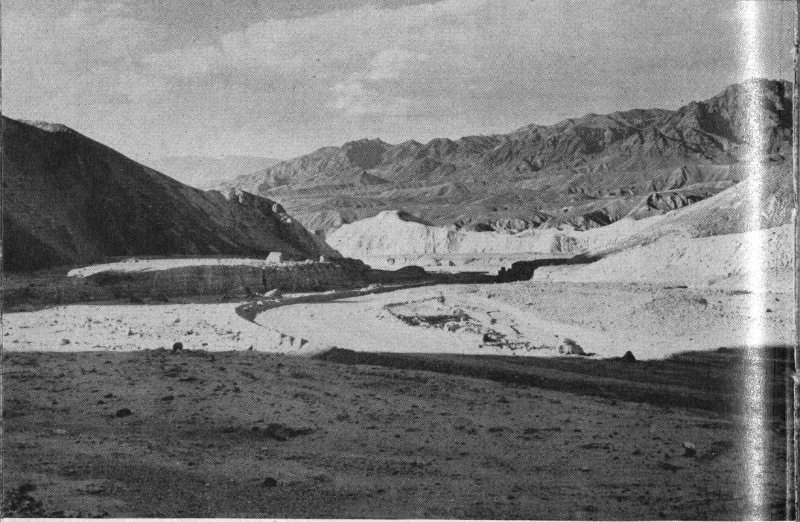

Marketing the borax presented a problem in transportation even more difficult than it did in Tibet. At first it was scraped from the flat surface of the valley where it looked like alkali. It was later discovered in ledge form in the foothills of the Funeral Mountains. The sight of this discovery was called Monte Blanco—now almost a forgotten name.

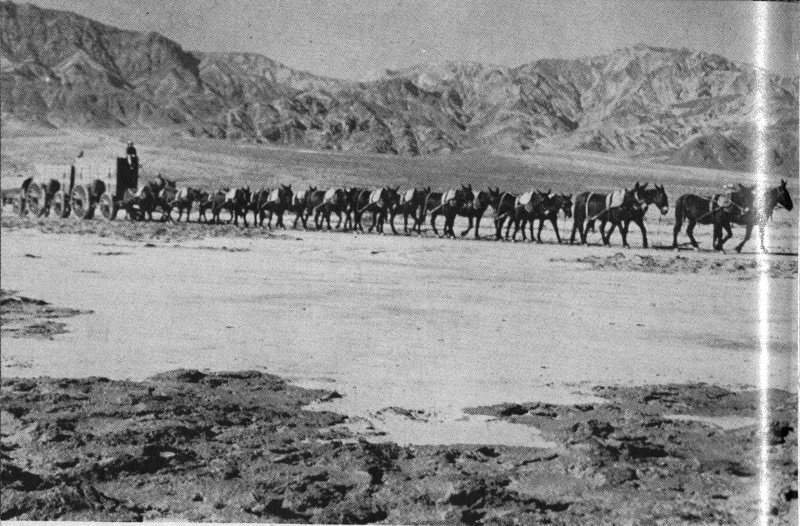

The borax was boiled in tanks and after crystallization was hauled by mule team across one hundred and sixty-five miles of mountainous desert at a pace of fifteen miles per day—if there were no accidents—or an average of twenty days for the round trip. The summer temperatures in the cooler hours of the night were 112 degrees; in the day, 120 to 134 (the highest ever recorded). There were only four water holes on the route. Hence, water had to be hauled for the team.

The borax was hauled to Daggett and Mojave and thence shipped to Alameda, California, to be refined. Charles Bennett, a rancher from Pahrump Valley, was among the first to contract the hauling of the raw product.

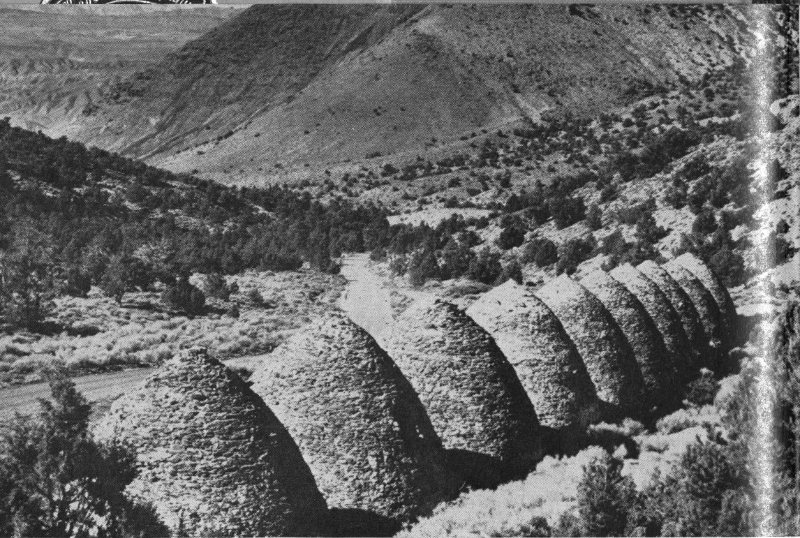

In 1883 J. W. S. Perry, superintendent of the borax company, decided the company should own its freighting service and under his direction the famous 20 mule team borax wagons with the enormous wheels were designed. Orders were given for ten wagons. Each weighed 7800 pounds. Two of these wagons formed a train, the load being 40,000 pounds. To the second wagon was attached a smaller one with a tank holding 1200 gallons of water.

“I’d leave around midnight,” Ed Stiles said. “Generally 110 or 112 degrees.”

The first hauls of these wagons were to Mojave, with overnight stations every sixteen miles. Thirty days were required for the round trip.

In the Eighties a prospector in the then booming Calico Mountains, between Barstow and Yermo discovered an ore that puzzled him. He showed it to others and though the bustling town of Calico was filled with miners from all parts of the world, none could identify it. Under the blow torch the crystalline surface crumbled. Out of curiosity he had it assayed. It proved to be calcium borate and was the world’s first knowledge of borax in that form. Previously it had been found in the form of “cotton ball.” The Pacific Coast Borax Company acquired the deposits; named the ore Colemanite in honor of W. T. Coleman.

Operations in Death Valley were suspended and transferred to the new deposit, which saved a ten to fifteen days’ haul besides providing a superior product. The deposit was exhausted however, in the early part 32 of the century when Colemanite was discovered in the Black Mountains and the first mine—the Lila C. began operations.

It is a bit ironical that during the depression of the Thirties, two prospectors who neither knew nor cared anything about borax were poking around Kramer in relatively flat country in sight of the paved highway between Barstow and Mojave when they found what is believed to be the world’s largest deposit of borax.

It was a good time for bargain hunters and was acquired by the Pacific Coast Borax Company and there in a town named Boron, all its borax is now produced.

Even before Aaron Winters or Isadore Daunet, John Searles was shipping borax out of Death Valley country. With his brother Dennis, member of the George party of 1861, Searles had returned and was developing gold and silver claims in the Slate Range overlooking a slimy marsh. They had a mill ready for operation when the Indians, then making war on the whites of Inyo county destroyed it with fire. A man of outstanding courage, Searles remained to recuperate his losses. He had read about the Trona deposits first found in the Nile Valley and was reminded of it when he put some of the water from the marsh in a vessel to boil and use for drinking. Later he noticed the formation of crystals and then suspecting borax he went to San Francisco with samples and sought backing. He found a promoter who after examining the samples, told him, “If the claims are what these samples indicate, I can get all the money you need....”

An analysis was made showing borax.

“But where is this stuff located?”

Searles told him as definitely as he could. He was invited to remain in San Francisco while a company could be organized. “It will take but a few days....”

Searles explained that he hadn’t filed on the ground and preferred to go back and protect the claim.

The suave promoter brushed his excuse aside. “Little chance of anybody’s going into that God forsaken hole.” He called an associate. “Take Mr. Searles in charge and show him San Francisco....”

Not a rounder, Searles bored quickly with night life. His funds ran low. He asked the loan of $25.

“Certainly....” His host stepped into an adjacent office, returning after a moment to say the cashier was out but that he had left instructions to give Searles whatever he wished.

Searles made trip after trip to the cashier’s office but never found him in and becoming suspicious, he pawned his watch and hurried home, arriving at midnight four days later.

The next morning a stranger came and something about his attire, his equipment, and his explanation of his presence didn’t ring true and Searles was wary even before the fellow, believing that Searles was still in San Francisco announced that he had been sent to find a man named Searles to look over some borax claims. “Do you know where they are?”

Searles thought quickly. He had not as yet located his monuments nor filed a notice. He pointed down the valley. “They’re about 20 miles ahead....”

The fellow went on his way and before he was out of sight, Searles was staking out the marsh and with one of the most colorful of Death Valley characters, Salty Bill Parkinson, began operations in 1872. Incorporated under the name of San Bernardino Borax Company, the business grew and was later sold to Borax Smith’s Pacific Coast Borax Company.

Once while Searles was away hunting grizzlies, the Indians who had burned his mill, raided his ranch and drove his mules across the range. Suspecting the Piutes, he got his rifle and two pistols.

“They’ll kill you,” he was warned.

“I’m going to get those mules,” Searles snapped and followed their tracks across the Slate Range and Panamint Valley. High in the overlooking mountains he came upon the Indians feasting upon one of the animals and was immediately attacked with bows and arrows. He killed seven bucks and the rest ran, but an Indian’s arrow was buried in his eye. He jerked the arrow out, later losing the eye, pushed on and recovered the rest of his mules. Thereafter the Piutes avoided Searles and his marsh because, they said, he possessed the “evil eye.”

On the same lake where Searles began operations, the town of Trona was established to house the employees and processing plants of the American Potash and Chemical Company. It was British owned, though this ownership was successfully concealed in the intricate corporate structure of the Pacific Coast Borax Company, but later sold for twelve million dollars to Hollanders who left the management as they found it. During World War II Uncle Sam discovered that the Hollanders were stooges for German financiers’ Potash Cartel.

The Alien Property Custodian took over and ordered the sale of the stock to Americans. Today it is what its name implies—an American company.

From the ooze where John Searles first camped to hunt grizzly bears, is being taken more than 100 commercial products and every day of your life you use one or more of them if you eat, bathe, or wear clothes, brush your teeth or deal with druggist, grocer, dentist or doctor.

Fearing exhaustion of the visible supply (the ooze is 70 feet deep) 34 tests were made in 1917 to determine what was below. Result, supply one century; value two billion dollars.

Here are a few things containing the product of the ooze. Fertilizer for your flowers, orchards, and fields. Baking soda, dyes, lubricating oils, paper. Ethyl gasoline, porcelain, medicines, fumigants, leathers, solvents, cosmetics, textiles, ceramics, chemical and pharmaceutical preparations.

About 1300 tons of these products are shipped out every day over a company-owned railroad and transshipped at Searles’ Station over the Southern Pacific, to go finally in one form or another into every home in America and most of those in the entire world.

The weird valley meanders southward from the lake through blown-up mountains gorgeously colored and grimly defiant—a trip to thrill the lover of the wild and rugged.

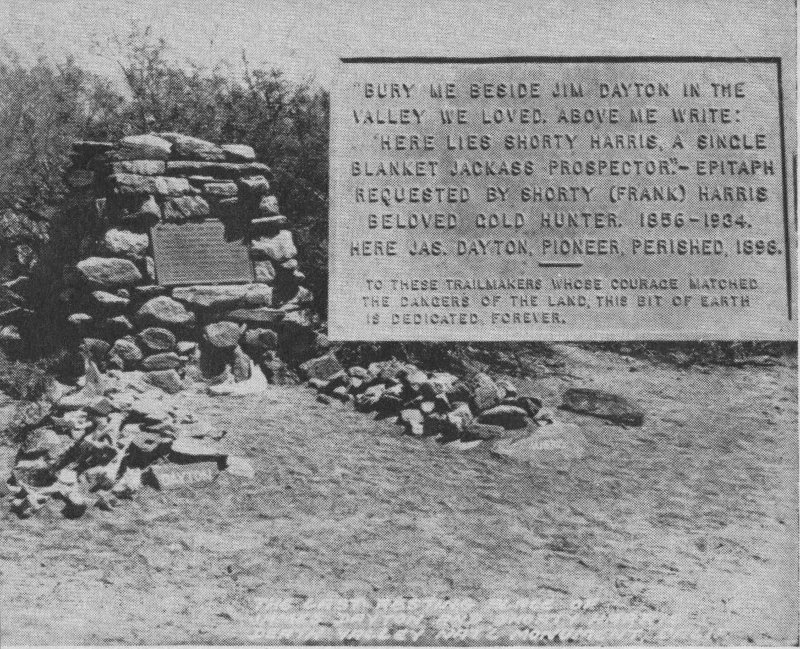

For years, on the edge of the road near Tule Hole, a rough slab marked Jim Dayton’s grave, on which were piled the bleached bones of Dayton’s horses. On the board were these words: “Jas. Dayton. Died 1898.”

The accuracy of the date of Dayton’s death as given on the bronze plaque on the monument and on the marker which it replaced, has been challenged. The author of this book wrote the epitaph for the monument and the date on it is the date which was on the original marker—an old ironing board that had belonged to Pauline Gower. In a snapshot made by the writer, the date 1898, burned into the board with a redhot poker shows clearly.

The two men who know most about the matter, Wash Cahill and Frank Hilton, whom he sent to find Dayton or his body, both declared the date on the marker correct.

The late Ed Stiles brought Dayton into Death Valley. Stiles was working for Jim McLaughlin (Stiles called him McGlothlin), who operated a freighting service with headquarters at Bishop. McLaughlin ordered Stiles to take a 12 mule team and report to the Eagle Borax Works in Death Valley. “I can’t give you any directions. You’ll just have to find the place.” Stiles had never been in Death Valley nor could he find anyone who had. It was like telling a man to start across the ocean and find a ship named Sally.

At Bishop Creek in Owens Valley Stiles decided he needed a helper. There he found but one person willing to go—a youngster barely out of his teens—Jim Dayton.

Dayton remained in Death Valley and somewhat late in life, on one of his trips out, romance entered. After painting an intriguing picture 36 of the lotus life a girl would find at Furnace Creek, he asked the lady to share it with him. She promptly accepted.

A few months later, the bride suggested that a trip out would make her love the lotus life even more and so in the summer of 1898 she tearfully departed. Soon she wrote Jim in effect that it hadn’t turned out as she had hoped. Instead, she had become reconciled to shade trees, green lawns, neighbors, and places to go and if he wanted to live with her again he would just have to abandon the Death Valley paradise.

Dayton loaded his wagon with all his possessions, called his dog and started for Daggett.

Wash Cahill, who was to become vice-president of the borax company, was then working at its Daggett office. Cahill received from Dayton a letter which he saw from the date inside and the postmark on the envelope, had been held somewhere for at least two weeks before it was mailed.

The letter contained Dayton’s resignation and explained why Dayton was leaving. He had left a reliable man in temporary charge and was bringing his household goods; also two horses which had been borrowed at Daggett.

Knowing that Dayton should have arrived in Daggett at least a week before the actual arrival of the letter, Cahill was alarmed and dispatched Frank Hilton, a teamster and handy man, and Dolph Lavares to see what had happened.

On the roadside at Tule Hole they found Dayton’s body, his dog patiently guarding it. Apparently Dayton had become ill, stopped to rest. “Maybe the sun beat him down. Maybe his ticker jammed,” said Shorty Harris, “but the horses were fouled in the harness and were standing up dead.”

There could be no flowers for Jim Dayton nor peal of organ. So they went to his wagon, loosened the shovel lashed to the coupling pole. They dug a hole beside the road, rolled Jim Dayton’s body into it.

The widow later settled in a comfortable house in town with neighbors close at hand. There she was trapped by fire. While the flames were consuming the building a man ran up. Someone said, “She’s in that upper room.” The brave and daring fellow tore his way through the crowd, leaped through the window into a room red with flames and dragged her out, her clothing still afire. He laid her down, beat out the flames, but she succumbed.

A multitude applauded the hero. A little later over in Nevada another multitude lynched him. Between heroism and depravity—what?

Although Tule Hole has long been a landmark of Death Valley, few know its story and this I believe to be its first publication.

One day while resting his team, Stiles noticed a patch of tules growing a short distance off the road and taking a shovel he walked over, started digging a hole on what he thought was a million to one chance of finding water, and thus reduce the load that had to be hauled for use between springs. “I hadn’t dug a foot,” he told me “before I struck water. I dug a ditch to let it run off and after it cleared I drank some, found it good and enlarged the hole.”

He went on to Daggett with his load. Repairs to his wagon train required a week and by the time he returned five weeks had elapsed. “I stopped the team opposite the tules, got out and started over to look at the hole I’d dug. When I got within a few yards three or four naked squaw hags scurried into the brush. I stopped and looked away toward the mountains to give ’em a chance to hide. Then I noticed two Indian bucks, each leading a riderless horse, headed for the Panamints. Then I knew what had happened.”

Ed Stiles was a desert man and knew his Indians. Somewhere up in a Panamint canyon the chief had called a powwow and when it was over the head men had gone from one wickiup to another and looked over all the toothless old crones who no longer were able to serve, yet consumed and were in the way. Then they had brought the horses and with two strong bucks to guard them, they had ridden down the canyon and out across the desert to the water hole. There the crones had slid to the ground. The bucks had dropped a sack of piñon nuts. Of course, the toothless hags could not crunch the nuts and even if they could, the nuts would not last long. Then they would have to crawl off into the scrawny brush and grabble for herbs or slap at grasshoppers, but these are quicker than palsied hands and in a little while the sun would beat them down.

The rest was up to God.

The distinction of driving the first 20 mule team has always been a matter of controversy. Over a nation-wide hook-up, the National Broadcasting Co. once presented a playlet based upon these conflicting claims. A few days afterward, at the annual Death Valley picnic held at Wilmington, John Delameter, a speaker, announced that he’d made considerable research and was prepared to name the person actually entitled to that honor. The crowd, including three claimants of the title, moved closer, their ears cupped in eager attention as Delameter began to speak. One of the claimants nudged my arm with a confident smile, whispered, “Now you’ll know....” A few feet away his rivals, their pale eyes fixed on the speaker, hunched forward to miss no word.

Mr. Delameter said: “There were several wagons of 16 mules and who drove the first of these, I do not know, but I do know who drove the first 20 mule team.”

Covertly and with gleams of triumph, the claimants eyed each other as Delameter paused to turn a page of his manuscript. Then with a loud voice he said: “I drove it myself!”

May God have mercy on his soul.

A few days later I rang the doorbell at the ranch house of Ed Stiles, almost surrounded by the city of San Bernardino. As no one answered, I walked to the rear, and across a field of green alfalfa saw a man pitching hay in a temperature of 120 degrees. It was Stiles who in 1876 was teaming in Bodie—toughest of the gold towns.

I sat down in the shade of his hay. He stood in the sun. I said, “Mr. Stiles, do you know who drove the first 20 mule team in Death Valley?”

He gave me a kind of et-tu, Brute look and smiled.

“In the fall of 1882 I was driving a 12 mule team from the Eagle Borax Works to Daggett. I met a man on a buckboard who asked if the team was for sale. I told him to write Mr. McLaughlin. It took 15 days to make the round trip and when I got back I met the same man. He showed me a bill of sale for the team and hired me to drive it. He had an eight mule team and a new red wagon, driven by a fellow named Webster. The man in the buckboard was Borax Smith.

“Al Maynard, foreman for Smith and Coleman, was at work grubbing out mesquite to plant alfalfa on what is now Furnace Creek Ranch. Maynard told me to take the tongue out of the new wagon and put a trailer tongue in it. ‘In the morning,’ he said, ‘hitch it to your wagon. Put a water wagon behind your trailer, hook up those eight mules with your team and go to Daggett.’

“That was the first time that a 20 mule team was driven out of Death Valley. Webster was supposed to swamp for me. But when he saw his new red wagon and mules hitched up with my outfit, he walked into the office and quit his job.”

The pleasure of your trip through the Big Sink will be enhanced if you know something about the structural features which are sure to arrest your attention.

For undetermined ages Death Valley was desert. Then rivers and lakes. Rivers dried. Lakes evaporated. Again, desert. It is believed that in thousands of years there have been no changes other than those caused by earthquakes and erosion.

It is no abuse of the superlative to say that the foremost authority upon Death Valley geology is Doctor Levi Noble, who has studied it under the auspices of the U.S. Geological Survey since 1917. He has ridden over more of it than anyone and because of his studies, earlier conclusions of geologists are scrapped today.

From a pamphlet published by the American Geological Society with the permission of the U. S. Dept. of Interior, now out of print, I quote a few passages which Doctor Noble, its author, once described to me as “dull reading, even for scientists.”

“The southern Death Valley region contains rocks of at least eight geologic systems whose aggregate thickness certainly exceeds 45,000 feet for the stratified rocks alone.”

“The dissected playa or lake beds in Amargosa Valley between Shoshone and Tecopa contain elephant remains that are Pleistocene....”

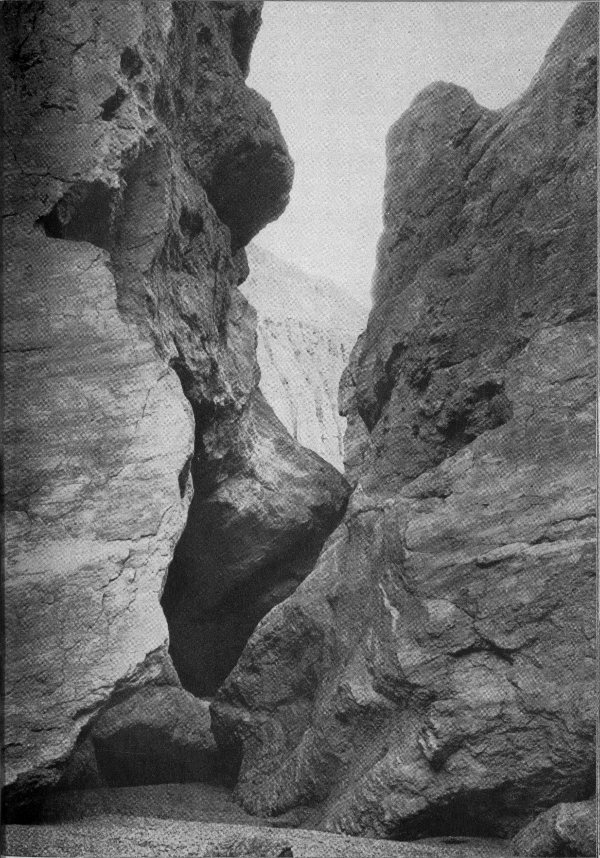

“Rainbow Mountain is one of the geological show places of the Death Valley region.... Here the Amargosa river has cut a canyon 1000 feet deep.... The mountain is made up of thrust slices of Cambrian and pre-Cambrian rocks alternating with slices of Tertiary rocks, all of which dip in general about 30 to 40 degrees eastward, but are also anticlinally arched.”

“None of the geologic terms in common use appear exactly to fit 40 this mosaic of large tightly packed individual blocks of different ages occupying a definite zone above a major thrust fault.”

The significant feature is that a stratum that began with creation may lie above one that is an infant in the age of rock—a puzzle that will engage men of Levi Noble’s talents for years to come. But one doesn’t have to be a member of the American Geological Society to find thrills in other gripping features.

Throughout the area south of Shoshone are many hot springs containing boron and fluorine—some with traces of radium. The water is believed to come from a buried river. The source of other hot springs in the Death Valley area is unknown.

More startling features were related to Shorty Harris and me at Bennett’s Well in the bottom of Death Valley where we met one of Shorty’s friends. Lanky and baked brown, in each wrinkle of his face the sun had etched a smile. “Shorty,” he said, “yachts will be sailing around here some day. There’s a passage to the sea, sure as hell.”

“What makes you think so?” Shorty asked.

“Those salt pools. Just come from there. I was watching the crystals; felt the ground move a little. Pool started sloshing. A sea serpent with eyes big as a wagon wheel and teeth full of kelp stuck his head up. Where’d he come from? No kelp in this valley. That prove anything?”

Ubehebe Crater is believed to have resulted from the only major change in the topography of the valley since its return to desert, but John Delameter, old time freighter, thought geologists didn’t know what they were talking about. “When I first saw Saratoga Spring I could straddle it. Full of fish four inches long. Next time, three springs and a lake. Fish shrunk to one inch and different shaped head.”

Actually these fish are the degenerate descendants of the larger fish that lived in the streams and lakes that once watered Death Valley—an interesting study in the survival of species. The real name, Cyprinodon Macularius, is too large a mouthful for the natives so they are called desert sardines, though they are in reality a small killifish.

Dan Breshnahan, in charge of a road crew working between Furnace Creek Inn and Stove Pipe Well, ordered some of the men to dig a hole to sink some piles. Two feet beneath a hard crust they encountered muck. When they hit the pile with a sledge it would bounce back. Dan put a board across the top. With a man on each end of the board, the rebound was prevented and the pile driven into hard earth. “I’m convinced that under that road is a lake of mire and Lord help the fellow who goes through,” Dan said.

A heavily loaded 20 mule team wagon driven by Delameter 41 broke the surface of this ooze and two days were required to get it out. To test the depth, he tied an anvil to his bridle rein and let it down. The lead line of a 20 mule team is 120 feet long. It sank (he said) the length of the line and reached no bottom.

On Ash Meadows, a few miles from Death Valley Junction and on the side of a mountain is what is known as The Devil’s Hole which it is said has no bottom. True or false, none has ever been found.

A steep trail leads down to the water which will then be over your head. Indians will tell you that a squaw fell into this hole within the memory of the living and that she was sucked to the bottom and came out at Big Spring several miles distant. The latter is a large hole in the middle of the desert and from its throat, also bottomless, pours a large volume of clear, warm water.

“Explored?” shouted Dad Fairbanks one day when a white-haired prospector declared every foot of Death Valley had been worked over. “It isn’t scratched!”

Only the day before (in 1934), Dr. Levi Noble had been working in the mountains overlooking the valley on the east rim. Through his field glasses he saw a formation that looked like a natural bridge. When he returned to Shoshone he phoned Harry Gower, Pacific Borax Co. official at Furnace Creek of his discovery and suggested that Gower investigate.

Since Furnace Creek Inn wanted such attractions for its guests, Gower went immediately and almost within rifle shot of a road used since the Seventies, he found the bridge.

That too is Death Valley—land of continual surprise.

Death Valley is the hottest spot in North America. The U.S. Army, in a test of clothing suitable for hot weather made some startling discoveries. According to records, on one day in every seven years the temperature reaches 180 on the valley floor. But five feet above ground where official temperatures are recorded the thermometer drops 55 degrees to 125.

The highest temperature ever recorded was 134 at Furnace Creek Ranch—only two degrees below the world’s record in Morocco. In 1913, the week of July 7-14, the temperature never got below 127. Official recording differs little from that of Arabia, India, and lower California, but the duration is longer.

Left in the sun, water in a pail of ordinary size will evaporate in an hour. Bodies decompose two or three hours after rigor mortis begins but some have been found in certain areas at higher altitudes dried like leather. A rattlesnake dropped into a bucket and set in the sun will die in 20 minutes.

The evaporation of salt from the body is rapid and many prospectors swallow a mouthful of common salt before going out into a killing sun.

One of the pitiable features of death on the desert is that bodies are found with fingers worn to the bone from frantic digging and often beneath the cadaver is water at two feet.

There is also legendary weather for outside consumption. Told to see Joe Ryan as a source of dependable information, a tourist approached Joe and asked what kind of temperature one would encounter in the valley.

“Heat is always exaggerated,” said Joe. “Of course it gets a little warm now and then. Hottest I ever saw was in August when I crossed the valley with Mike Lane. I was walking ahead when I heard Mike coughing. I looked around. Seemed to be choking and I went back. Mike held out his palm and in it was a gold nugget and Mike was madder’n hell. ‘My teeth melted,’ Mike wailed. ‘I’m going to kill that dentist. He told me they would stand heat up to 500 degrees.’”

I met an engaging liar at Bradbury Well one day. He was gloriously drunk and was telling the group about him that he was a great grand-son of the fabulous Paul Bunyan.

“Of course,” he said, “Gramp was a mighty man, but he was dumb at that. One time I saw him put a handful of pebbles in his mouth and blow ’em one at a time at a flock of wild geese flying a mile high. He got every goose, but how did he end up? Not so good. He straddled the Pacific ocean one day and prowled around in China, and saw a cross-eyed pigeon-toed midget with buck teeth. Worse, she had a temper that would melt pig-iron.

“Gramp went nuts over her. What happened? He married her. She had some trained fleas. If Gramp got sassy, she put fleas in his ears and ants in his pants and stood by, laughing at him, while he scratched himself to death. Hell of an end for Gramp, wasn’t it?”

In the late fall, winter, and early spring perfect days are the rule and if you are among those who like uncharted trails, do not hurry. Then when night comes you will climb a moonbeam and play among the stars. You will learn too, that life goes on away from box scores, radio puns, and girls with a flair for Veuve Cliquot.

The Indians of the Death Valley country were dog eaters—both those of Shoshone and Piute origin. Both had undoubtedly degenerated as a result of migrations. The Shoshones (Snakes) had originally lived in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. The Piutes in Utah, Idaho, and Nevada.

The true blood connection of coast Indians may well be a matter of dispute. “Almost every 15 or 20 leagues you’ll find a distinct dialect,” was said of California Indians. (Boscana in Robinson’s Life in California, p. 220.) Most of them were hardly above the animal in intelligence or morality. Though the Death Valley Indians are called Shoshone and Piutes, to what extent their blood justifies the classification is the white man’s guess.

Those whom Dr. French found in the Panamint said they had no tribal name. Many California tribes were given names by the whites, these names being the American’s interpretation of a sound uttered by one group to designate another. “They do not seem to have any names for themselves.” (Schoolcraft’s Arch., Vol. 3.)

All seem to agree however, that the farther north the Indian lived, the more intelligent he was and the better his physique—which would indicate a relation to the better diet in the lush, well-watered and game-filled valleys and foothills. Some of the women are described by early writers as “exceedingly pretty.” Others, “flat-faced and pudgy.” “The Indians in the northern portion ... are vastly superior in stature and intellect to those found in the southern part.” (Hubbard, Golden Era, 1856.)

Certainly those found in Death Valley country reflected in their persons and in their character the niggardly land and the struggle for 44 survival upon it. They were treacherous as its terrain. Cruel as its cactus. Tenacious as its stunted life.

It is interesting to note the range of opinion and the conclusions drawn by earlier travelers.

Of the Shoshones: “Very rigid in their morals.” (Remi and Brenchley’s Journal, Vol. 1, p. 85.)

“They of all men are lowest, lying in a state of semi-torpor in holes in the ground in winter and in spring, crawling forth and eating grass on their hands and knees until able to regain their feet ... living in filth ... no bridles on their passions ... surely room for no missing links between them and brutes.” (Bancroft’s Native Races, Vol. 1, p. 440.)

“It is common practice ... to gamble away their wives and children.... A husband will prostitute his wife to a stranger for a trifling present.” (Ibid. ch. 4, Vol. 1.)

“Our Piute has a peculiar way of getting a foretaste of connubial bliss—cohabiting experimentally with his intended for two or three days previous to the nuptial ceremony, at the end of which time either party can stay further proceedings to indulge further trials until a companion more congenial is found.” (S. F. Medical Press, Vol. 3, p. 155. See also, Lewis and Clark’s Travels, p. 307.)

“The Piutes are the most degraded and least intellectual Indians known to trappers.” (Farnham’s Life, p. 336.)

“Pah-utes are undoubtedly the most docile Indians on the continent.” (Indian Affairs Report, 1859, p. 374.)

“Honest and trustworthy, but lazy and dirty,” is said of the Shoshones. (Remi and Brenchley’s Journal, p. 123.) Some ethnologists declare they cannot be identified with any other American tribe.