FIFTEENTH BOOK OF THE

FAITH PROMOTING SERIES

DESIGNED FOR THE INSTRUCTION

AND ENCOURAGEMENT OF YOUNG

LATTER-DAY SAINTS

COMPILED AND PUBLISHED BY

GEO. C. LAMBERT

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

1914

April 8, 1914

To the First Presidency, City.

Dear Brethren:

I have had a desire for a long time past to resume the publication of the Faith Promoting Series that I originated and published something like thirty-five years ago, but which has been suspended for almost thirty years.

I received the sanction of the Church authorities when the publication of this series was commenced, and had ample evidence afterwards of the popularity of the volumes issued, and of the general benefit resulting therefrom. I now desire your sanction in what I may do in publishing additional volumes; and hope to subserve the interests of the Church and promote true faith only in what I publish.

If you deem it necessary to appoint a committee to whom I may refer any matter concerning which there may be a question as to propriety, etc., I shall be glad to have you do so.

I am prepared to assume all financial responsibility, and believe, with the experience I have had, I shall be able to do effective work in the selection and preparation of the matter.

I intend to make the volumes about one hundred pages each, and hope to be able to sell them at twenty-five cents per volume.

I have the matter partially prepared for two volumes, the first to relate to Temple work, and to be called "Treasures in Heaven," the second to contain a variety of incidents and experiences, and to be called "Choice Memories."

A waiting your kind consideration and reply, and with kindest regards, I remain

Your Brother,

GEO. C. LAMBERT.

April 30, 1914

Elder George C. Lambert, City.

Dear Brother:

We learn by yours of the 28th inst. that you desire to resume the publication of the "Faith Promoting Series," discontinued some thirty years ago, and we take pleasure in informing you that you have our sanction to do this, and that we have appointed Elders George F. Richards, A. W. Ivins and Joseph F. Smith, Jr. as a committee to read the manuscript.

With kind regards,

Your Brethren,

JOSEPH F. SMITH, ANTHON H. LUND, CHARLES W. PENROSE,

First Presidency.

No lesson taught by the Savior during his ministry in mortality was more frequently and thoroughly impressed than that of unselfish service. Of those who labored solely for the things of this world, or for praise or the honors that men can bestow, He had a habit of saying: "They have their reward." If they obtained that which they strove for they were already repaid: they were entitled to nothing more. Of the rich He said, "Ye have received your consolation." It was not sufficient that man should seek to benefit or bring happiness alone to those they loved. Even that He evidently regarded as a species of selfishness, as implied by the saying: "For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye?" "For sinners do even the same." His exhortation was: "Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal; but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal."

All this was not intended to imply that wealth itself was intrinsically bad, or that poverty had any essential virtue, except as a means to an end. The rule was, as expressed by the great Teacher, that "where the treasure is, there will the heart be also." A sublime test upon this point was that made of the young man who applied to the Savior upon one occasion to know what good thing he could do to gain eternal life. Though he was able to say that he had kept all the commandments from his youth up, it was apparent to the Master that his heart was set upon the wealth he possessed, as evidence of which he turned away sorrowfully when required by the Savior to surrender his possessions, for the benefit of the poor, and follow Him.

The Gospel as revealed anew in our day has shed a flood of light upon the subject of salvation, and the conditions upon which it is predicated. The glorious principle of salvation for the dead, as revealed through the Prophet Joseph Smith, has awakened a desire in the hearts of thousands of earnest seekers after truth to do a vicarious work for the benefit of their dead relatives and friends, that they may share in all the blessings and privileges of the Gospel. In this work, as well as in the preaching of the Gospel to the living, have avenues been opened up for unselfish work, which, as it involves no earthly reward, is clearly in the line of laying up treasures in heaven, as distinguished from the work of amassing treasures upon earth which absorbs the attention of so many of the earth's inhabitants. That the recital of some typical examples of sacrifices unselfishly made in the interest of others, and th—e joy experienced therein, may tend to promote faith in those who read the same and incite them also to lay up treasures in heaven, this volume is published in continuation of the "Faith Promoting Series," originated and published by the present author about thirty-five years ago.

Birth of Niels—Obscure Childhood—Crippled, Helpless Condition—Gospel Preached—Taught Needlework—Training in Bible and Lutheran Creed—A Prophetic Priest—Remarkable Prediction Concerning Niels. Page 7.

Death of his Mother—Life in Aalborg—Conversion to Mormonism—Heavenly Message to Elder Kempe—His Obedience thereto—Baptism of Niels—His Relatives Ashamed of Him—Proposition to Make Him a Lutheran Preacher. Page 12.

Desire to Migrate—Discouraging Prospects—Help From an Unexpected Source—Religious Discrimination—Contends for His Rights—Effects a Compromise—Characteristics of Niels—Spiritual Impressions and Premonitions. Page 17.

A Vision and its Pre-Mortal Counterpart—Beset by Evil Spirits—Deliverance Therefrom—Preparations to Migrate—Long Voyage—Toilsome Journey—Lost on the Plains—Help from the Lord. Page 21.

Feat as a Pedestrian—Lessons Learned and Ambition Developed While Traveling—Arrival in Salt Lake City—Employment Diligently Sought—Precarious Success—Miraculously Fed. Page 27.

Invests in Real Estate—Acquires a Home—Vicarious Work in Logan Temple—Consequent Elation—Promise to a Dying Friend—Gratuitous Fulfillment in Manti Temple. Page 33.

Completion of Salt Lake Temple—His Work Therein—Sister Corradi Inspired to Apply to Him—Devoted Work for her Kindred—His Severe Afflictions—Saving Work for 2200—Graceful Old Age. Page 37.

Modern Stoic—His Modest Obscurity—What Religion Has Done for Niels—Philosophic Way in Which He Views Death. Page 40.

Purpose Essential to Success—Birth and Parentage of Carolina Corradi—Her Mother's Prescience—Preparation for Future Career—Devoted Work in Behalf of Dead Kindred. Page 47.

A Rich Man's Handicap—Wealth Not Essentially Bad—But Qualities its Possession Develops a Bar to Salvation—Typical Case of a Man Reared in Affluence—Unpromising Start in Married Life—How He Became Interested in Temple Work—Worthy Example in Recent Years. Page 55.

Prediction from Malachi Fulfilled—Birth and Childhood of Mary Alice Cannon—Cannon Family Embrace the Gospel—Migrate—Mother's Death at Sea—Arrival at Nauvoo—Father's Death—Her Marriage. Page 65.

Strenuous Life in Nauvoo—City Besieged—Thrilling Experience—Miracle of Quails—Run Over by Wagon—Wagon Sinks to Bottom of River—Life in Utah—Mission Abroad—Her Posterity. Page 74.

Night Workers Who Serve in the Temple During the Day—Many Women Serve at Great Personal Sacrifice—Temple Work a Boon to the Blind. Page 89.

BIRTH OF NIELS—OBSCURE CHILDHOOD—CRIPPLED, HELPLESS CONDITION—GOSPEL PREACHED—TAUGHT NEEDLEWORK—TRAINING IN BIBLE AND LUTHERAN CREED—A PROPHETIC PRIEST—REMARKABLE PREDICTION CONCERNING NIELS.

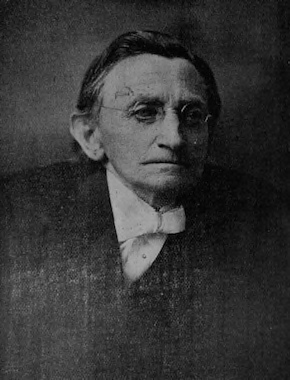

Perhaps no better example of unselfish service in the interest of others, of patience and forbearance under the burden of a serious physical handicap and courage and persistence in a labor of love and sacrifice can be found than is afforded in the life of the hero whose portrait is herewith presented.

Niels P. L. Eskildz was born May 31, 1836, at Lindholm, County of Aalborg, Denmark, only a few miles from the city of Aalborg, which is celebrated as being the birthplace of President Anthon H. Lund. The parents of Niels were unassuming, country folks, with nothing to distinguish them from their industrious and respectable neighbors except their rather unusual size and a certain pride of bearing and correctness of speech, due to their superior education, and the fact that they were both descendants in a direct line from noble, titled families.

They had a small farm, the cultivation of which furnished them little more than a modest living, and the father combined the occupation of butcher with that of farmer, by slaughtering animals and selling meat in the village market place every Wednesday and Saturday.

Niels P. L. Eskildz

Niels was the youngest of the family, having two brothers of almost gigantic stature and a sister who, when grown, was the largest woman in that part of Denmark. Niels also, would doubtless have grown to be an unusually large man had he not met with an awful accident when ten years of age.

Denmark is a country almost without fences, the farms being separated one from another by imaginary lines. Instead of the cows and sheep owned by the farmers being allowed to range at will in pastures, the custom was and still is to stake them out individually, and lead them in at night. As a rule the cows are models of decorum, and one of the prettiest as well as commonest sights of the country is to see a boy or girl marching a number of cows, like so many soldiers, in double file and close rank from the pasture to the barn.

Niels, having been sent by his parents to thus bring a cow in from the field, the creature, though usually docile, suddenly became fractious and, running around the boy, tangled him up in the rope, and then frantically dragged him through a grain field and against numerous obstructions before she could be stopped. When released the poor boy was found to have a broken thigh and other serious injuries, from the effects of which he was bedfast for more than three years. It was feared he never would recover, but his patient mother gave him the most devoted attention and relieved the tedium of his helplessness by teaching him needlework, at which she was an adept, and by reading to him. In course on time he grew strong enough to be propped up in a chair and thus carried into the open air, but the exertion was probably too much for him, as he soon had a relapse, and during the ensuing two years spent most of his time in bed. His spine by degrees became so curved and deformed that, while his legs were nearly of normal length, his body had the appearance of having been crumpled down thereon, and his large, well-shaped head crowded down between his shoulders.

In the year 1850 Apostle Erastus Snow arrived in Denmark as a missionary. He had not been there long when the Gospel influence began to be felt and converts to flock to his standard. One family among the residents of Lindholm embraced the Gospel, and soon found themselves somewhat notorious because of the attention they received from the local Lutheran priest, near whose chapel the family lived, and his frequent public comments on their abandonment of the Lutheran faith and acceptance of the unpopular doctrines of "Mormonism."

In those days the Lutheran church held almost undisputed sway throughout Denmark, and the invariable rule was for children to be diligently taught the Bible and drilled in a knowledge of the Lutheran creed from their infancy. When the children attain the age of about thirteen years they are required to appear before the priest for a series of examinations, as to their knowledge of these subjects before being confirmed as members of the Lutheran church.

When Niels was fourteen years old, and was barely able to hobble about a little on crutches, he was cited to appear with a class of dozen or more children before the priest, to be catechised. This they did many times until they were able to answer satisfactorily all the questions propounded to them. At about the first of these meetings a young girl asked to be excused from the examinations, because her parents had joined the "Mormons," and she expected to. She cited in support of her plea, that the King of Denmark had granted religious liberty. Her request was complied with by the priest, who proceeded to comment on "Mormonism" then and at every subsequent meeting in a way that indicated that he must have been studying "Mormon" literature, and Niels very strongly suspected that the priest was really converted to "Mormonism," although he either lacked the courage to embrace it, or considered it impolitic to do so. Whether this surmise was correct or not, the priest seemed to have "Mormonism" constantly in his mind, and his frequent allusions to its doctrines and the scripture supporting the same had the effect of converting Niels to "Mormonism." Though he did not then declare his belief in the Gospel, he had not from that time a doubt of its truth.

That priest, whose name was Holger Christopher Kongslev Thryde, was a very peculiar man, a thorough scriptorian, a keen reasoner and withal quite inspirational. When the class of which Niels was a member had received sufficient training by him to appear for public examination and confirmation as members of the Lutheran church, they were all notified to be present at the regular Sunday service in the chapel. There they were separately catechised by the priest in presence of the congregation. Their answers being satisfactory, he asked each in turn as to his willingness to enter into covenant to serve God. On being told that he was, the priest said "then give your heart to God and your hand to me." Holding the child by the right hand, he then placed his left hand upon the youthful head, confirmed him as a member of the Lutheran church and exhorted him to faithfulness or indulged in predictions concerning his future, apparently as the spirit prompted him. Of one boy he expressed regret that he had been confirmed a Lutheran, for he would soon abandon the faith. The sequel proved this prediction to be true, for the boy soon left his birthplace to live among relatives who were Baptists, and accordingly became a Baptist.

When Niels was confirmed, the priest proceeded to say: "The Lord has laid a heavy hand upon you in your youth, which will be a hard cross for you to bear through life; but it was for a wise purpose—to prepare you for a great work that you do not understand now. After you have traveled thousands of miles to a strange land you know not, you will there eventually have a chance to go into the sanctuary of the Lord to do a work for your father's family and your ancestors that they did not understand or know anything about."

This prediction made a deep impression upon the mind of Niels, who remembered every word of it, and felt that somehow it would be fulfilled, though he could not then conceive how or when. That he, a helpless cripple and confirmed invalid; without money or influential friends, should ever travel thousands of miles over land and sea, seemed very improbable; indeed, it seemed very unlikely that he would live long enough to make such a journey if he were financially able.

DEATH OF HIS MOTHER—LIFE IN AALBORG—CONVERSION TO MORMONISM—HEAVENLY MESSAGE TO ELDER KEMPE—HIS OBEDIENCE THERETO—BAPTISM OF NIELS—HIS RELATIVES ASHAMED OF HIM—PROPOSITION TO MAKE HIM A LUTHERAN PREACHER.

If the details of the life of Niels for the next six years were written it would be a record of helpless dependence and privation. To the surprise of all who knew him, he continued to live, and even gain a little strength. Life at home had become unbearable since the death of his mother, which occurred December 6, 1854.

In the fall of 1856, when he was twenty years of age, Niels left home and went to live among relatives in Aalborg, where he had a checkered experience, often being made to feel that he was in the way and that his welcome was worn out, but occasionally encouraged by real kindness and genuine charity. One lady in particular took a great interest in him, and, finding that he had some skill in needle work, encouraged him to practice a kind that was much in vogue among ladies, and through her kindly efforts he obtained considerable profitable work from many aristocratic women.

Soon after removing to Aalborg he met and became somewhat acquainted with some "Mormons," a family of Saints being close neighbors to his aunt. His partial investigation of the Gospel then confirmed his early conviction that it was the truth, but his dependent condition, and the opposition of his relatives to such an unpopular religion, led him to defer embracing it.

It was not until November 1, 1862, six years after he first attended a "Mormon" meeting, that he embraced the Gospel, and then under peculiar circumstances. Christoffer Jensen Kempe, who afterwards became well known in Utah and Arizona, was laboring as a "Mormon" missionary in that part of Denmark. One very stormy night he had found lodgings in a barn, about forty-two miles from Aalborg. Some time after retiring to rest he was aroused by feeling a hand laid upon his shoulder and hearing a voice tell him to get up and go to Aalborg and baptize the cripple, Larsen, whom he had seen at the Saints' meetings—that if he ever joined the church he would have to be baptized the next evening. Obedient to the voice of the spirit, he arose and set out afoot in the storm. He walked the entire distance, and on his arrival in Aalborg he called upon Niels at his lodgings and informed him that he had come to baptize him. Niels immediately asked what prompted him to come, as he had not even announced his intention of joining the church. Elder Kempe related the visitation he had received forty-two miles distant, and told of his journey for the special purpose, and added that he would like while he was at it to baptize Niels' brother and sister-in-law who were then living in Aalborg, and whom he had met and talked with on the subject of religion. Niels ventured the opinion that neither of the relatives mentioned had any serious intention of embracing "Mormonism," and that he was sure they would not if they learned their crippled brother intended to do so. "However," he said, "you may try them, and if you succeed in getting their consent you may call back for me, and I will be ready."

The Elder promptly repaired to the brother's house and broached the subject of baptism to the couple, saying he was going to do some baptizing that night, and if they wished he would baptize them. They at first favored the proposition, but when he, hoping to hasten and make certain their decision, mentioned that Niels was going to be baptized they lost all interest in the subject and refused to be baptized.

Returning to Niels, the Elder informed him of his failure and disappointment. Niels was not at all surprised, and told the Elder he should not be disappointed in him, as he was ready. They accordingly made their way that very night a considerable distance out of town, to find a suitable place for the performance of the ordinance, and Niels was initiated into the Church by baptism November 1, 1862.

Some circumstances of which Niels was in ignorance at the time of his baptism, but which he afterwards learned of, may furnish the sequel to what was meant by the heavenly warning to Elder Kempe that Niels would have to be baptized that very evening if he ever joined the church at all.

Something like consternation had prevailed among the aristocratic members of the Lutheran church in and around Aalborg about that time, in consequence of so many of the members being converted to "Mormonism." As a rule they were not the wealthy members who accepted of the Gospel, as taught by the "Mormon" missionaries, but they included those who had been regarded as among the very best and most faithful members of the church, and they were joining the "Mormon" ranks in such numbers that they seemed for awhile to threaten the very existence of some of the Lutheran congregations.

The priests and their influential, loyal supporters held numerous meetings, to discuss measures for checking this defection and restoring the waning fealty of their flocks. Among other schemes resorted to was that of organizing a society or club among the wealthy women of the Church, and the collecting by them of a large sum of money, to effect a kind of revival in the church. The lady mentioned as having taken such an interest in procuring work for Niels was one of the leaders in this movement. She had discovered that Niels was a very observant individual, was a logical reasoner, had a most retentive memory and a very thorough knowledge of the scriptures. It had been her habit while Niels was employed at her home to test him upon these points. Occasionally she would ask him what the preacher had talked about at the service on the previous Sabbath, or to relate some particular thing that he had heard or read. He would not only be able to repeat, almost verbatim what he had heard or read, but to mimic the gestures of the speakers as well.

Possibly she and her aristocratic associates had been impressed with his mental vigor and been led to think that he might be utilized in some way in arousing an interest in church affairs. Possibly it may have been sympathy for him and the kindness of their hearts that prompted them to think of him in connection with their revival project. What they did was to get up a numerously signed petition to the bishop of the diocese, to appoint Niels to act as a lay preacher or exhorter—a kind of home missionary—to visit the members at their homes, hold semi-private services, etc., and to be paid a regular stipend therefor out of the funds they had collected. It could not have been anything attractive about his personality that suggested him for such a position, for in appearance he was repellant rather than attractive. Even the very dogs on the street shunned him or snarled at him and refused to be friendly or sociable with him. It could not have been any zeal that he manifested in the Lutheran church that caused him to be thought of, for although he frequently attended the Lutheran service (more as a matter of policy than otherwise, for he obtained his employment chiefly from the Lutheran ladies) he even more commonly attended the Latter-day Saint services, and had several times been chided by his Lutheran acquaintances for doing so. Of course Niels was not consulted in regard to the plans of the Lutheran ladies concerning him. His projected appointment was intended to be a surprise to him. The bishop announced to the ladies' society that he had complied with their petition and appointed Niels to act as lay preacher on the very day of the latter's baptism, as already mentioned, and that evening a meeting was held in the local Lutheran church, and the announcement was made public. The inquiry was then made of the congregation as to where Niels lived, so that the news might be sent to him, but no person present seemed to know. One man, however, arose in the congregation and volunteered the information that he was acquainted with the brother of Niels (the same one whom Elder Kempe had hoped to baptize,) and that he could carry the news to him of the honor that had come to Niels. He was accordingly commissioned to do so, but when he went to the brother the following day he learned to his surprise that he was just one day too late; Niels had embraced "Mormonism" the night before. He knew it, for he had witnessed the baptism.

Niels learned, soon after he was confirmed a Latter-day Saint, of the proposition to make him a preacher of the Lutheran religion, and of course was surprised thereat. He didn't regret having missed the opportunity. Being sure (as he had been ever since he was a child) that "Mormonism" was true, he would have had to stultify himself to advocate any other creed. He was glad, however, that the temptation never was squarely presented to him, lest in his weakness and poverty he might have yielded to it.

DESIRE TO MIGRATE—DISCOURAGING PROSPECTS—HELP FROM AN UNEXPECTED SOURCE—RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION—CONTENDS FOR HIS RIGHTS—EFFECTS A COMPROMISE—CHARACTERISTICS OF NIELS—SPIRITUAL IMPRESSIONS AND PREMONITIONS.

In common with all the Saints in Scandinavia at that period, Niels had a strong desire to migrate to Zion, and was as ready as any of his countrymen to accomplish that end by rigid economy and self denial; but how he was ever going to obtain the price of his fare was a problem for which he could see no solution. His income from charity and his own earnings had been so meagre and precarious for years that it had been his habit from necessity to test how little it required to sustain life. To accumulate anything honestly had practically been out of the question. How then could he ever hope to save so large an amount as his fare to Utah would cost?

In the face of this discouraging prospect help came to him from a most unexpected source, which Niels has ever since regarded as providential. He had become acquainted with a kind hearted Lutheran priest, whose sympathy was doubtless excited by his helpless, dependent condition. One day when they chanced to meet, the priest mentioned the fact that a person had recently died who for several years previous had been enjoying a legacy bequeathed to the parish many years before by a charitable person, when about to die. One of the conditions of this bequest was that it should be held for the support of some worthy person who was physically helpless and dependent. Niels was reminded that he was physically and morally qualified to benefit by that legacy, and encouraged by the suggestion that he might possibly succeed as its beneficiary if he made application to the parish officers. He did so without delay, and to his great gratification he was granted the benefit of the legacy. It was not very much—it only amounted to about ten dollars per quarter, or $40.00 per year—but by maintaining the same system of economy he had previously practiced, he managed to save the greater part of it, and began to look forward to the time when his savings would be sufficient to pay for his emigration.

Niels had not enjoyed this legacy very long, however, when the parish officers learned that he was a "Mormon," and stopped payment of the stipend. They soon found, though, that Niels was not to be disposed of so easily. Friendless and helpless and cripple though he was, he was not lacking in courage and a sense of the justice of his cause. Boldly he went before the parish officers and demanded the payment of the stipend that had been withheld, and its continuance while he lived. Assuming that the person who made the bequest had not stipulated that it should be held exclusively for Lutherans, he charged that they had no right to apply any religious test to him, and defended his cause so well that his hearers were forced to admit that he was right. After a very lengthly parley they reluctantly offered to compromise by allowing him the benefit of the legacy for a limited time. He refused the offer and contended for his life interest, and reminded them that notwithstanding his weakly condition he was liable to live a long time, as his ancestors had been noted for their longevity. When they were thoroughly impressed with this possibility, he offered a compromise—proposing that the amount of twelve quarterly payments be advanced to him from the funds of the legacy, on condition that he surrender his right to any more, and migrate to Utah. This they finally agreed to, and thus Niels was enabled to come to Utah with a company of Saints which left Copenhagen May 17, 1866.

Before mentioning the details of the journey or his life in Utah it may be appropriate to revert to some things that tend to illustrate the character of Niels. He is possessed of a strong and independent mind, fixed convictions and marvelous will power for one whose body is so frail. His spirituality is highly developed; but one would not know it from his manner. He is never exuberant, enthusiastic or talkative, but sedate, reserved and self-possessed. He is a keen observer, a good listener, a logical and discriminating thinker and a thoughtful and discreet talker. He has a high sense of honor, a respect for others' rights and feelings, charity for the weaknesses and failings of others, and for one who has been so helplessly dependent the greater part of his life, is wonderfully free from servility. He is grateful for kindness and favors shown him, but never truculent or even obsequious. He has reasons satisfactory to himself for his actions, but these reasons are not always apparent to others, and because of this his motives have often been misconstrued, even by his friends and co-religionists. He has few confidants, and lives as it were in a world of his own, being reticent to a marked degree, but confident and self-reliant as to his course in life. Though diffident about admitting it, his spiritual impressions have largely controlled his actions throughout his life. When only ten years old the premonition of impending disaster was so strong within him, that just prior to the dreadful accident which left him maimed for life, he plead with his parents not to send him for the cow, and when they persisted in doing so, warned them that they would be sorry for if all their lives. They did not mean to be unkind or heartless; indeed, they had great love for their children, and the father was especially indulgent; but they had strict ideas in regard to family discipline, and when once the word of either one was passed as to any requirement on the part of the children, both were unyielding in demanding compliance. They saw no danger in his bringing the cow in from the pasture. He had done so many times before, without any harm resulting therefrom, and they saw no reason why he should not do so again, with impunity. The sequel, however, proved that his premonition was correct.

A VISION AND ITS PRE-MORTAL COUNTERPART—BESET BY EVIL SPIRITS—DELIVERANCE THEREFROM—PREPARATIONS TO MIGRATE—LONG VOYAGE—TOILSOME JOURNEY—LOST ON THE PLAINS—HELP FROM THE LORD.

His crippled, helpless condition was a great source of sorrow to Niels, and instead of his becoming gradually reconciled thereto, as it might be supposed that he would, he seemed to brood over it more the older he grew. He belonged to a proud and rather dignified family, and was naturally very proud himself, but realized that he did not present a dignified appearance. He was constantly reminded that people were repelled rather than attracted by him, and this of course wounded his pride and made him miserable.

During the summer preceding his baptism, after a day of extreme melancholy, an incident occurred that produced an entire change in his feelings. While engaged preparing his evening meal a glorious vision burst upon his view. It was not a single scene that he beheld, but a series of them. He compares them to the modern moving pictures, for want of a better illustration. He beheld as with his natural sight, but he realized afterwards that it was with the eye of the spirit that he saw what he did. His understanding was appealed to as well as his sight. What was shown him related to his existence in the spirit world, mortal experience and future rewards. He comprehended, as if by intuition, that he had witnessed a somewhat similar scene in his pre-mortal state, and been given the opportunity of choosing the class of reward he would like to attain to. He knew that he had deliberately made his choice. He realized which of the rewards he had selected, and understood that such a reward was only to be gained by mortal suffering—that, in fact, he must be a cripple and endure severe physical pain, privation and ignominy. He was conscious too that he still insisted upon having that reward, and accepted and agreed to the conditions.

He emerged from the vision with a settled conviction that to rebel against or even to repine at his fate, was not only a reproach to an Alwise Father whose care had been over him notwithstanding his seeming abandonment, but a base violation of the deliberate promise and agreement he had entered into, and upon the observance of which his future reward depended.

Whatever opinion others may entertain concerning the philosophy involved in this theory, is a matter of absolute indifference to Niels. He does not advocate it; he does not seek to apply it to any other case; but he has unshaken faith in it so far as his own case is concerned. Whether true or not, the fact remains that he has derived comfort, satisfaction, resolution and fortitude from it. He has ever since been resigned to his affliction, and, though never mirthful, is serene and composed and uncomplaining. He has always felt that the vision was granted to him by the Lord for a wise and merciful purpose—that he might, through a better understanding of his duty, be able to remain steadfast thereto.

In striking contrast to this experience was that which occurred during the night following his baptism. Evil spirits seemed to fill the room in which he had retired to sleep. They were not only terribly visible, but he heard voices also, taunting him with having acted foolishly in submitting to baptism and joining the Latter-day Saints. He was told that he had deserted the only friends he ever had, and would find no more among the "Mormons," who would allow him to die of starvation rather than assist him. That he had no means of earning a livlihood in the far western land to which the Saints all hoped to migrate, and he would never cease to regret it if he ever went there. This torment was kept up incessantly until he sought relief in prayer, and three times he got out of bed and tried to pray before he succeeded in doing so. Then his fervent pleading unto the Lord for power to withstand the temptation of the evil one, and to hold fast to the truth, brought relief to him. The evil spirits gradually, and with apparent reluctance, withdrew, and peace came to his soul, with the assurance that the Lord approved of his embracing the Gospel, and that he could safely rely upon the Lord for future guidance.

Preparations were soon made to migrate to Utah, although Niels was seriously ill. In addition to his other troubles, he had for years been afflicted with asthma, and he had such difficulty in breathing that for a long time he had not been able to recline, having to sleep, if at all, in a sitting posture. He was also so frail and weak at the time that many of his acquaintances expressed a fear that he would not live to make the journey, and some even predicted that he would die while crossing the ocean. Not at all daunted, however, by these pessimists, he determined to start with the very first company of migrating Saints, and soon arranged with a newly-married couple and a young single man who were ambitious to migrate, to care for him on the journey, carry and look after his luggage, etc., in return for certain financial aid which he was able and willing to afford them. He realized that it would be a long and tiresome trip, and his natural independence was exhibited in thus arranging beforehand for the help he might require, lest he might be regarded as a public burden. The journey, as planned, was not as direct as those commonly pursued in more recent years, nor nearly so expeditious. The company assembled at Copenhagen, whence they proceeded by steamer to Kiel, in Germany, and from there took train for Altonia. At Hamburg, on the river Elbe, they boarded an ocean sailing vessel, the "Kenilworth," bound for New York. The voyage lasted eight weeks, long enough for the passengers to get well acquainted with one another.

They had expected to proceed westward from New York, (or rather from the New Jersey side of the Hudson river) by rail, but Thomas Taylor, who was the Church Immigration Agent in New York at that time, had learned before their arrival that all the lines of railway extending westward from that point had entered into a combine to demand a higher rate for transporting companies of Latter-day Saints than those previously prevailing. Determined not to submit to their extortion, he discovered before the company arrived that one line of railway extending westward from New Haven, Connecticut, was not in the combine, and would transport the company at the old rate, and he decided to patronize it. The road was either poorly equipped with cars or lacked time before the arrival of the company to make the necessary arrangements for convenient transportation.

The accommodations on the train as it was made up were rather meager; in fact, it was a cattle car that Niels rode in, and the passengers had to sit or he on the floor. The road bed appeared to lack ballast, and the ride was a jolty, tiresome one—particularly hard on Niels, who was so painfully affected by the jolting that he sought relief by bracing his hands against the floor on either side of him, thereby partially sustaining the weight of his body and easing the jar. The shaking was so great that both doors fell off the car, and, to cap the climax, some of the cars ran off the track, the one in which Niels rode standing crosswise of the track, and with two of the wheels broken off it, when the train came to a halt. This occurred on the bank of a river in Southern Canada, and the passengers breathed a sigh of relief when they discovered what a narrow escape they had from being plunged into the river.

From New York the company therefore proceeded by coast steamer to New Haven, and from there by train to St. Joseph Missouri, where they were transferred to a river boat that during the next two days took them up the Missouri to Wyoming Hills, a few miles from Nebraska City, from which point they were to be conveyed by ox train to Salt Lake City, more than a thousand miles distant.

Before leaving Denmark, he had not been able to walk as much as two hundred yards without stopping to rest, but he gradually improved while crossing the sea, and, though temporarily prostrated with the heat while on the river steamer, he rallied before the overland journey was undertaken. Before starting from the Missouri river the able-bodied passengers were requested to walk as much as possible on the journey, as the wagons were heavily loaded and the strength of the oxen had to be conserved, as they had an eight weeks trip before them.

Though far from being able-bodied, Niels determined to do his best at walking. He accordingly set out bravely with the other pedestrians, with whom, however, he was unable to keep up, as his gait was like that of a snail. His habit was to walk until overtaken by the train, or until he was so fatigued that he could not proceed further, when he would get into a wagon and ride. Occasionally he succeeded by perseverance in walking all day long, and was necessarily most of the time alone. By starting early, as soon as breakfast was over, and before the teams had been hitched up, he would be able to keep ahead of the train, and yet soon be outdistanced by his more able companions. Upon one occasion he got lost as a result of being alone. He arrived at a point where the road which he was following diverged into two. Not knowing which of the two he should take, he happened to choose the wrong one, and traveled for a long distance without being able to see those who had preceded him or the wagons in the rear. Without apprehension, he trudged along until he arrived at a river which was too deep and swift for him to wade, and which was spanned by a rude foot bridge, consisting of two or three lengths of a single round pole, supported where the ends joined amid-stream by two poles set up in the form of a cross, with the lower ends firmly imbedded in the stream, and securely lashed with rawhide at the intersection. The swiftness of the current and the distance from the foot bridge down to the stream made him dizzy when he looked down, so that he despaired of being able to cross the bridge, and yet felt that he must do so to overtake the train that he supposed must have forded at a point much lower down stream. In his emergency he knelt in prayer on the river bank, reminding the Lord of his dependence upon Him and appealing unto Him for help. He arose with a feeling of confidence, and without any trepidation or dizziness set out and walked along the pole as steadily as if he had been a tight-rope performer. Then, following his impression as to the course he ought to take, he walked on until he overtook the train, encamped, some time after nightfall, and when men were about to be dispatched to search for him.

FEAT AS A PEDESTRIAN—LESSONS LEARNED AND AMBITION DEVELOPED WHILE TRAVELING—ARRIVAL IN SALT LAKE CITY—EMPLOYMENT DILIGENTLY SOUGHT—PRECARIOUS SUCCESS—MIRACULOUSLY FED.

The journey on the whole, though tiresome, was not otherwise unpleasant. He enjoyed the society of his fellow emigrants, and felt that he had been blessed of the Lord beyond his most sanguine hopes; for notwithstanding his feeble condition when starting, he succeeded in walking more than three fourths of the way across the plains. He had also been cured of the asthma with which he had been so long afflicted—not suddenly, but so gradually that he hardly realized that he was outgrowing it.

He had also been benefited otherwise by the experience gained on the journey. His views of life had become broadened by travel, and by the evidences of thrift and enterprise which he witnessed on his journey through the states, as well as by the possibilities of development he could forsee in the great and boundless west. He felt like a bird released from a cage after a lengthy confinement therein. He enjoyed his freedom and learned to commune with Nature as he never had done before. His knowledge of human nature had also been very materially added to since leaving his native land. There are few conditions under which human nature can be studied to better advantage than while making such a journey over sea and land as that which he had passed through. The crowding together of a large company in the hold of a ship for eight long weeks, with meagre accommodations and food generally insufficient and frequently bad, is certain to develop selfishness, impatience and irritability where these qualities exist even in latent form. His fellow passengers were actuated by the noblest motives in migrating. They had accepted the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ, some of them at the sacrifice of material comforts, and most of them at the cost of friends and prestige. Some of them had been sneered at and persecuted in their native land, and had their former friends and relatives turn to be their bitter enemies, solely because of their accepting of and adhering to such an unpopular creed. They had withstood all that, and, with faith still unshaken, were willing to brave other trials and face the hardships of this long voyage and journey, and the problems incident to life in a new and wild country, to gain religious freedom, and because they regarded it as a divine requirement. But human nature, even though tempered by religious convictions, is apt to assert itself sometimes, and the helpless, dependent condition of Niels placed him in the position of a spectator, with ample opportunity to observe all that passed, and to study human nature during the voyage as he never had done before.

Disputes occasionally arose among the passengers, which sometimes waxed warm and developed into angry quarrels, all of which Niels noticed but never took part in. Possibly because he was always an observer of but never a participant in these affairs, he was several times appealed to as an arbitrator, to decide between the disputants and effect a reconciliation. Without making any pretentions to judicial wisdom, he was, through strict impartiality, and tact in offering reproof without giving offense, and especially by appealing to the religious obligations of the parties to the strife, enabled to do effective work as a peace-maker, and to gain respect therefor. He couldn't refrain from indulging in a little mental philosophy on such occasions, and making note of the fact that the tongue is a dangerous member if allowed to wag too freely.

Three times during the voyage the ship had taken fire, always at night, as a result of the cook's carelessness, and a general panic among the passengers, if nothing worse, was narrowly averted. Upon the first of these occasions the fire had gained sufficient headway before it was discovered for a rather large bole to be burned through the floor almost directly above where Niels had his bunk, and when the first alarm was sounded Niels looked upward and saw the fire and noticed the presence of smoke in the hold. He was able to "keep his head" and helped in some measure in quelling the excitement of his fellows, many of whom became almost frantic when they learned that the ship was on fire, and that the hatches were fastened down, so that the passengers were shut up in the hold like rats in a trap.

It occurred to Niels that the hatches had been closed by order of the ship's officers to prevent a panic. He saw the futility of rebelling against the measure, and counseled calmness and patience; and was so calm and self-possessed himself that some of the more excited ones listened to him, made a strong effort to control themselves, and seemed ashamed at having been overcome by alarm.

The overland journey on the cars and the eight weeks' trip by ox train in crossing the plains were not less fruitful in opportunities to study character under trying conditions, and for the personal display of those amenities that distinguish gentility from boorishness and Christian charity from heartless selfishness. It was alike creditable to the restraining influence of the Gospel upon the company in general, and to the fine discernment and keen discrimination of Niels, that he did not lose faith in his fellows because of the weakness they exhibited under trying conditions—that he arrived in Utah with a keener appreciation of the Gospel's power to mold human character to conform to the divine pattern. He too had been tried as never before in his life, and the consciousness of his own failings made him charitable for those of others.

Some of his experiences on the plains had a peculiarly western flavor. Although the company of which he was a member never actually came in conflict with the Indians, they had a number of thrills due to rumors of Indian hostilities before or behind them. One night the ox train emigrant company camped on one side of a river which they expected to cross early the next morning, while a mule train loaded with merchandise camped on the opposite bank of the same stream. During the night a marauding band of Indians stole and ran off about ninety head of mules from the train last mentioned, driving them all right past the camp of the passenger train, and so close to it that Niels heard them galloping by, and wondered at first whether the noise was caused by the oxen stampeding. Another experience that was new and strange to him was seeing a rattle snake dart into a hole over which he was about to make his bed. It didn't produce a very comfortable feeling, but the bed was made right over the hole and the snake created no disturbance during the night.

Before the journey ended Niels began to feel almost as if he were a western man himself, so thoroughly had he entered into the spirit of all that pertained to it. He had engaged in a struggle with a large number of fellows for a common goal, and had developed ability that he had never before known himself to be possessed of, and now, on reaching it, he was ambitious to be a factor in the further unfolding of God's purposes.

On his arrival in Salt Lake City Niels sought employment by which to earn a subsistence, for he could not bear the thought of being always dependent upon others. He found, however, that such work as he was capable of doing was neither remunerative nor easily obtained. His first job was at glove-making. He found two of his fellow country women engaged in the business of making and selling buckskin gloves, their customers in the main being overland travelers. He persuaded them to let him learn the business from them, and then furnish him employment when they had more work than they could do themselves. The work was precarious at best, and not at all lucrative, but he appreciated having anything to do, and being able to earn ever so little. After attaining to some skill in that line, the demand for buckskin gloves fell off until there was no longer any encouragement to make them. Then he learned to sew uppers for ladies' shoes, and obtained a limited amount of work in that line, but machines soon displaced hand sewing of shoes. His means of earning a livelihood seemed to be diminishing rather than increasing, but with independence unabated, he sought work at whatever he could do (which was almost exclusively limited to sewing) and went without what he could not earn, or which did not come to him voluntarily, without making his wants known. In a land of plenty, surrounded by people who were amply able to help him, and who would willingly have shared with him their last meal, he lived almost like a recluse, and sometimes actually suffered for want of food. Two or three instances of uncharitableness and lack of sympathy sealed his lips against any admission of his real condition or complaint, and nerved him up to go without what he could not earn, or die trying. How little he subsisted upon for certain extended periods is almost beyond belief, and he probably would not have lived to tell it had not the Lord mercifully and miraculously replenished his larder as He did in the case of the widow of old who fed the prophet Elijah. Many times he scraped up the last saucerful of flour to make a cake, only to find as much more in the sack when hunger again impelled him to search for it. And so it happened that while his faith in mankind sometimes wavered, his faith in the Almighty grew stronger.

It must not be supposed from this that he was wholly without friends, or that his existence was a cheerless one; but he had an aversion to testing the friendship of his fellows by making known his wants, and a feeling that his friends would last longer if not used too much. He had entirely too much independence for a pauper, and too little bodily strength to competently make his way in the world without help. His circumstances varied. Sometimes for a considerable period fortune would favor him to a limited extent, his health being such that he could search for and obtain work and accumulate a little. He had the thrifty disposition that characterized the Scandinavian race, and his natural bent was to save some portion of it, however little he might earn. He had the "home-making" instinct as it would be termed if he were a bird—the disposition to build or acquire a nest of his own, however humble it might be, and so he labored to that end. In this, however, he met with many reverses. Illness would occasionally befall him, and his petty hoard would be exhausted before he could again resume his earning and saving. At quite an early stage of his Utah existence he invested five dollars, the savings of a long period, in a city lot in what is now the Twenty-seventh Ward of Salt Lake City, at a time when lots on the north bench, away above the inhabited district, could be had for the price of surveying. He could not afford to build upon it; in fact, it was only by heroic effort that he succeeded in paying the small tax upon it from year to year; but at the inception of the boom in real estate in 1888 he succeeded in selling that lot for $500.00. The possibility of owning a home loomed up before him as it never had done before, and from that time he began looking for a bargain in real estate.

INVESTS IN REAL ESTATE—ACQUIRES A HOME—VICARIOUS WORK IN LOGAN TEMPLE—CONSEQUENT ELATION—PROMISE TO A DYING FRIEND—GRATUITOUS FULFILLMENT IN MANTI TEMPLE.

In the course of a few years he found an opportunity of buying a small city lot north west of the capital grounds, with a rather old house upon it, for the modest sum which his capital represented, and he actually became a landlord. He rented part of it to the former owner, who had lost the property through mortgaging it and being unable to meet the payments when his notes fell due. His income from the rental was only $5.00 per month, and it required half of that to pay the taxes upon the property; but he had a shelter for himself as well—not very comfortable it was true, but much more so than some of the houses he had occupied—and it was his own. It was all the more appreciated when he thought of the improbability of his ever owning a home of any kind had he remained in his native land. He could now look forward with more hope to his declining years, when age would naturally add to his decrepitude.

When Niels accepted of the Gospel in his native land, no feature of it was more attractive to him than the promise of salvation for the dead contained therein. He found comfort in the assurance he obtained of personal salvation through compliance with the Gospel principles, and he was anxious to do something if possible that his ancestors and friends who had died without a knowledge of the Gospel should share in the Gospel privileges. When the Temple in Logan was completed and opened for ordinance work, he joyfully journeyed thither and spent eight weeks in receiving ordinances for the benefit of dead relatives. He felt that he was coming into his own, that he was accomplishing something that made life desirable. There was something exalting about the thought that he, deformed and weak and frail though he was, could do all for the salvation of his dead kindred and friends that the most able-bodied man in the community could do. He had long admired the missionaries who left their homes in Utah and the surrounding states, and, at infinite sacrifice, went forth into the

various nations of the earth to proclaim the Gospel message, without hope of earthly reward. The sole reason for their doing so was that they had been called by those whom they regarded as the Lord's earthly representatives to so labor, and because they regarded the Gospel as so priceless that they were anxious to have its benefits extended to all humanity. He, too, appreciated the Gospel, and his love for his fellows would have enabled him to find joy in laboring as a missionary, but, alas! he could never hope to engage in that labor because of his physical disabilities. But here was a labor which had for its object the same purpose, in which in point of ability he measured up to the full stature of the best of his fellows; and who should say that the work done in behalf of the dead is not just as important as that done for the living? He had never engaged in anything that so increased his self respect and made him feel that he was of some consequence in the world as this work in the Temple, and he regretted when necessity compelled him to abandon this labor which had such a savor of heaven about it and "come down to earth," figuratively speaking, by seeking such employment as he could engage in to earn the meagre necessaries of his subsistence.

Niels and his home

A considerable period passed afterward with little to relieve the monotony of his existence, during which, however, he again succeeded in accumulating something. In the meantime the Temple at Manti had been completed and ordinance work was being performed therein.

It happened that an old gentleman named Nielsen with whom Niels had years before, (while he was a resident of Salt Lake City,) been somewhat acquainted, had located at Manti while the Temple was in course of construction, and indulged in the hope of spending his declining years in laboring therein for the benefit of his dead kindred. Before being able or ready so to do, however, he had been stricken with sickness, and, at the solicitation of a daughter who was living in Salt Lake City, and who was the wife of a Catholic, had come up to reside with her and be nursed back to health. Instead of recovering, however, he continued to grow worse until his life was despaired of. During his illness he worried constantly over the fact that the work in the Temple which his heart had been so set upon performing for his dead kindred had never been done, and there now seemed no hope of his doing it, for he felt that he must soon die. In his emergency he thought about Niels as a friend whose services he might enlist, and induced his daughter to send for him to come and listen to her father's dying request. Niels came, and found his old friend almost in the throes of death. Being asked if he would do the work in the Temple which his friend had neglected, he consented without hesitancy, to pacify the dying man, and wrote down at his dictation the names of about seventy of his dead relatives, in whose behalf he wished the work performed. He was told that a certain sister living in Manti had promised to perform the work for the females, and could be relied upon to do so, and that it would only be necessary for him to see that she did it, and to do himself the work for the males.

After receiving the promise from Niels that he would attend to the matter, the old gentleman seemed satisfied, and soon died in peace. Niels then realized, as he had not done before, the responsibility that rested upon him, in consequence of his promise. He had never made a promise even to a person who was well without faithfully fulfilling it, and his promise made to a dying man seemed doubly binding. He must fulfill that if he never lived to do anything else. With this impressed upon his mind he soon journeyed to Manti and called upon the sister who had promised his dead friend to serve in the Temple for the female relatives. He found her so ill that there was little hope of her ever being able to keep her promise, and so he conscientiously applied himself to the task of fulfilling completely the commission assigned him. He hired sisters to do the work for the female dead, and he spent ten weeks in the Manti Temple, in constant labor for the male dead kindred of his friend Nielsen, and felt satisfaction in having done all that duty and honor could require of him in the matter.

COMPLETION OF SALT LAKE TEMPLE—HIS WORK THEREIN—SISTER CORRADI INSPIRED TO APPLY TO HIM—DEVOTED WORK FOR HER KINDRED—HIS SEVERE AFFLICTIONS—SAVING WORK FOR 2200—GRACEFUL OLD AGE.

Niels looked forward with fond anticipation to the completion of the Salt Lake Temple. He felt that now, that he had found his true vocation, he would like to devote all the time to Temple work that his health and means would permit, and he could do this to much better advantage in his home city than if he had to travel a long distance to reach a Temple, and then make special arrangements for his board and lodging. He commenced his labors three weeks after the Temple opened for ordinance work. He not only found great comfort and satisfaction in the work, (which he scrupulously devoted his time to whenever able to do so,) but, through the acquaintances he formed there, he obtained a considerable amount of employment in the sewing line, especially in the making of temple clothing, at which he became quite an expert. He was not able to work continuously; indeed, he had many spells of illness that confined him to the house and occasionally to his bed for days and weeks at a time, but he has long been known as one of the most earnest and devoted workers in the Temple. When he had officiated for all his dead kindred and friends concerning whom he had sufficiently definite information, he found others who were anxious to have him officiate for their dead kindred on the usual terms when men are so employed, (seventy-five cents per day,) and he so labored whenever able to do so. He has, however, officiated gratuitously for hundreds of people at the instance of friends or relatives who were unable to pay therefor. A case in point was that of a poor Scandinavian sister who died a few years since in this city. She left a list of fifty dead relatives for whom she had been unable to officiate, and he took up the work for the males and hunted up women acquaintances who were willing to officiate for the females.

A few years since he was called upon by a Sister Corradi, whom he only knew by sight, who desired to employ him to officiate for her male kindred dead, saying the Spirit had manifested to her that he was the person to whom she should apply. He consented, and has worked almost exclusively for her list since, and has enough names left to keep him occupied for about another year. Having a spell of illness some time since, he told Sister Corradi she had better find some one else to finish her work, as he feared he might not be able to do so. She, however, refused to believe that he was going to die soon, or fail to finish her work, and said she knew he was going to live to do it. She may be right. Now that he has lived so long (he was seventy-eight years old in May) there is reason to hope that he has several years yet to remain in mortality. It will soon be forty-eight years since he arrived in Utah, notwithstanding the predictions that he would not live to make the journey. It is nearly sixty-eight years since he met with the accident that left him deformed and crippled for life, and during that time he has never been free from pain, though it has varied in degree, being much more intense at some times than others. For many years hernia was added to his other afflictions, but he was healed of that in answer to prayer. About four years ago he lost the use of his voice, and has not since been able to speak above a whisper. In spite, however, of all these handicaps he has accomplished a work of self-sacrifice for the salvation of others that any able-bodied man of his age, desiring the welfare of his fellows, might well be proud of. He has officiated for fully twenty-two hundred persons in all the temple ordinances necessary to place them on a par with the living who have received these ordinances in their own behalf. All this in addition to the work he has had done in behalf of numerous female dead. Truly he has earned for himself the distinction of being a "Savior upon Mount Zion." The crucible of suffering to which he has been so long subjected has had a sanctifying and exalting effect upon him, and eliminated from his character all semblance of sordidness. His struggle for existence has developed the strong traits of his character that otherwise might have remained dormant, and his beneficent concern for others has helped him to bear with equanimity, if not to forget his own troubles. Even age seems to sit lightly upon him. Few who see him ever suspect his advanced age. The peevish, crabbed disposition that so frequently characterizes old age is never manifested by him. Instead, he wears the patient, serene expression of one who lives for a noble purpose, and indulges only in clean and wholesome thoughts.

A MODERN STOIC—HIS MODEST OBSCURITY—WHAT RELIGION HAS DONE FOR NIELS—PHILOSOPHIC WAY IN WHICH HE VIEWS DEATH.

Of the many who have witnessed Niels pursuing his toilsome way between his home and the Temple—a distance of about a mile—leaning upon his crutch and moving along at a slow but steady gait, perhaps not one has had a definite idea of what a heroic effort it has required for him to walk at all, and how his constant pain has been increased thereby.

Perhaps none of his fellow workers in the temple, who are in the daily habit of gazing upon his sphinx-like countenance as he silently passes among them, ever even dream that he is the best modern example of the stoic that this region has ever known, the physical agony that he suffers being never betrayed by word or facial expression.

Though casually known to many, he has scarcely been intimate with any. Even the facts pertaining to his life that are herein divulged, had to be fairly pried out of him by degrees, and they will doubtless be a revelation to many of his acquaintances when they read this recital. If his real condition had been generally known in the past, his every want would have been anticipated and supplied by his kind-hearted neighbors or the relief society. The chivalrous boy scouts might have adopted him as their protege, and done what they could to make his home cheerful, or otherwise lighten his burdens, and dyspeptics and other victims of luxurious living might have been making pilgrimages to his house to learn the secret of his long and useful life under such unfavorable conditions.

Possibly it is as well that he has been allowed to make his own way in the world. If he had been petted and pampered, and not had the incentive of want to spur him to exertion, he probably would never have accomplished anything worth mentioning, or that would have distinguished him from the great number of unfortunates that only excite our pity.

Niels acknowledges his indebtedness to the Gospel for all the comfort he has experienced in life. Indeed, without its sustaining power, it is doubtful whether he could have lived as long as he has, or retained his reason, if he had so lived. Without it, he could have had no desire to live; and, failing to find relief in death, his bodily suffering would probably have made of him a raving maniac or a driveling imbecile. As already mentioned, he was converted to the Gospel some time before he was baptized. He has never since entertained a doubt as to its truth. One might as well try to convince him that the sun does not shine, as that the Gospel is not true. Since his baptism he has been unwavering in his devotion to his religion. He has doubtless got more out of his religion than most adherents do. It has been the controlling inspiration of his life. He has been zealous, without being fanatical; devout, without outward expression. He has been a regular attendant at meetings (until he became in recent years too deaf to hear the preaching,) but never ambitious to take part therein. He feels amply repaid in the joy and satisfaction that have come to him for all the labors he has performed, and all the sufferings he has endured. He has no fear of death, but does not court it. He is content to live as long as the Lord is willing to have him do so [1]. He seeks no notoriety. He is the very personification of modesty. He is willing to be regarded as a grain of dust, an insignificant atom, and plod on in obscurity during the remainder of his mortal existence, as he has done in the past, without attracting any attention.

The author of this sketch has known Niels casually for years, but never discovered his real character until quite recently. For aught he knows, he may be the original discoverer. He regards as a very great compliment from Niels, the statement that he understood his character and motives as no one else had done before. He sought the acquaintance and confidence of Niels—was not sought by him. He it was, and not Niels, who conceived the idea of reducing to writing some of the incidents of his eventful life, and who surprised him later with a proposition to publish the same. The author is responsible for all deductions expressed herein, the facts alone having been somewhat reluctantly mentioned by Niels, but he has perused the story and endorsed it as correct, with some evident misgiving as to the possible resultant notoriety.

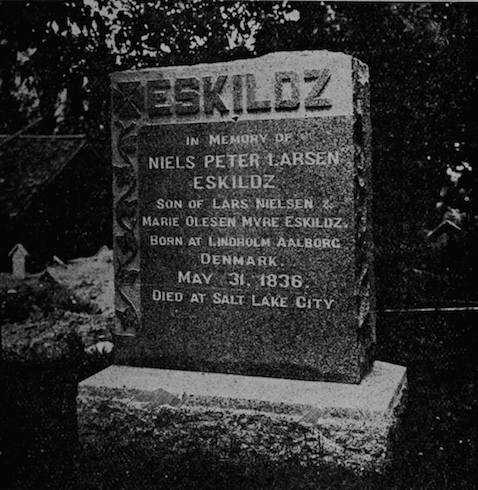

His Tombstone

If benefits to the many constitute the true standard by which success should be gauged, the life of Niels has certainly been a successful one; and the record herein set forth of the adverse conditions which have surrounded him, and his wonderful accomplishments in view thereof, should be an inspiration to every person who feels that his life's burden is heavy, and who is privileged to read this simple recital.

If the unselfish work to which Niels has devoted such a large part of his life had no other beneficial effect than to sweeten the lives and render lovable the characters of those who engage therein; to develop in them genuine love for their fellows and true charity—a willingness to benefit others without hope of reward therefor—and to make them cheerful, and hopeful and buoyant when otherwise they might be despondent and gloomy, surely that work is not in vain. Indeed it would even then compare favorably with almost any other that claims the attention of mankind.

If the "Mormon" theory be correct, the Gospel ordinances absolutely essential to the salvation and exaltation of mankind may be received by the living vicariously for the benefit of the dead. The dead, too, through an intelligent acceptance in the spirit world of the conditions of salvation, including the vicarious work voluntarily undertaken in their behalf on earth, may enjoy all the Gospel privileges.

Assuming that this theory is correct, what more important labor could a person engage in than that performed in the Temples? Is there any work on earth more free from the taint of selfishness? Is there anything a person could engage in that savors more of true Christian charity? Is not the satisfaction experienced by such earnest, sincere, conscientious people as Niels a strong evidence of the truth and efficacy of the work? Is not the assurance that Niels and thousands of others have received through the testimony of the Spirit, as to the work being acceptable to the dead in whose behalf it is done, and agreeable to the will of the Almighty, worthy of consideration?

The work done in the temple in behalf of the dead differs in this respect from other forms of charity—there is no danger of it making the one who performs it vainglorious. He is not open to the suspicion that the Pharisees of old were, in their giving of alms—a desire for applause, or "to be seen of men." Niels has not become puffed up because of what he has accomplished. He does not pose as anybody's benefactor. He assumes no heroic airs. There is no halo surrounding him such as "limners give to be the beloved disciple." He is just a modest, humble, obscure cripple, known to his neighbors, who are sufficiently acquainted with him to call him by name as Niels Larsen [2]; who is content to live and die without attaining to any distinction, who is advertised for the first time in this recital, and this without any desire or request on his part. He was the most insignificant and unpromising (not to say despised) of all his kindred, the tag end, as it were, of the aristocratic and once powerful families from which he had descended. He is the only one of a numerous kindred (so far as known) who has accepted of the Gospel. Possibly others of them, as well as the brother and sister-in-law already mentioned, have rejected the Gospel because of their shame of him.

Is it not possible that this stone which these builders of the family's reputation rejected may yet become the chief corner? That this despised of all his race may yet become the head of it? In view of the vast work that he has accomplished in behalf of his progenitors, may we not anticipate the grateful homage that he will receive from them in the next world, when he, as a resurrected being, will stand in their midst—not as a cripple, deformed, and dwarfed, and weak, and racked with pain, as he has been during most of his mortal career, but resplendent in all the glory of a perfected manhood, his physical body conforming in stature and appearance to his spiritual body, a very king among his fellows! Imagine, too, the joyful acclaim with which he will then be greeted by the numerous host who are not of his immediate kindred, for whose salvation he has unselfishly labored in mortality. Then will the pain and suffering and fatigue and humiliation which he endured in this life seem as nothing compared with the treasures in heaven which he will receive, and the limits and besetments of mortality be forgotten and swallowed up in its fruition—the joys and glories of an endless immortality.

Footnotes:

1. Niels has a very confident feeling that he will live to be 82 years of age, but whether the call comes to quit this mortal life sooner or later he intends to be prepared for it, and the completeness of his arrangements for his burial and for perpetuating a knowledge of his burial place indicates the complacency with which he regards death. Some time since he purchased a quarter of a lot in the cemetery, and had a very substantial granite monument made to his order and erected thereon. An inscription upon it gives his name, date and place of his birth, his parentage, and Salt Lake City as the place of his death, with blank space below upon which to chisel in the date of his passing away. He also keeps his burial clothes, made by himself, all nicely laundried, in readiness to place upon his body when death shall overtake him. This too is another illustration of his independence, and disposition to do things himself rather than trust to others.Since the erection of his tombstone, a lady who was somewhat acquainted with him happened to be in the cemetery and saw it. She read the inscription with surprise and sorrow. She failed to notice that the date of his death was lacking, and very naturally concluded that he had died and been buried, and was surprised that it could have happened without the news of it having reached her. She mourned to think she would never see him again, and that she had not even attended his funeral and manifested the respect she had for one whose suffering and inoffensiveness had so strongly appealed to her. In a pensive mood she returned home and told her friends how shocked and sorrow stricken she was at learning for the first time on seeing his monument of the death of her friend.

A few days later she was tripping across Main Street without any thought of death in her mind, when she suddenly beheld his familiar figure slowly moving down the side walk. She was so startled at sight of what she thought must be an apparition that she stood transfixed until she was aroused by the hoot of an approaching automobile, and narrowly escaped being knocked down and run over.

2. A custom prevails very generally among the peasantry throughout Scandinavia of changing the surname from generation to generation, while among the aristocracy the rule is to maintain the same surname in a family as one generation succeeds another. An exception to this latter rule sometimes occurs when a branch of an aristocratic family does not inherit wealth, or through some misfortune becomes financially reduced, and has to take rank per force with the peasantry. Then, notwithstanding the aristocratic lineage, the peasant method of changing the surname of the progeny from father to son is followed.As already mentioned in this narrative, Niels was of aristocratic lineage on both his father's and mother's side. They were, however, of minor branches that did not inherit much wealth. The father, though given in infancy the family surname of Eskildz, was known more generally throughout his lifetime by his given name of Lars Nielsen, and called Eskildz more as a nickname than otherwise, or as a means of distinguishing him from others having the name of Lars Nielsen. When Niels was born he was named Niels Larsen, in accordance with the peasant custom, and it was not until he commenced his work in the house of the Lord that he assumed his rightful ancestral name, and is even now scarcely known outside of the Temple by the name of Eskildz.

Niels' father and mother were second cousins. His mother's maiden name was Marie Olesen Myre. As may be inferred from the relationship existing between them before marriage, theirs was not the first marriage between the Eskildz and Myre families. Some branches of these two families were very wealthy and influential when Niels was a boy, which fact, however, was of no advantage to their poorer relatives, among whom were Niels and his parents.

PURPOSE ESSENTIAL TO SUCCESS—BIRTH AND PARENTAGE OF CAROLINA CORRADI—HER MOTHER'S PRESCIENCE—PREPARATION FOR FUTURE CAREER—DEVOTED WORK IN BEHALF OF DEAD KINDRED.

Few people have accomplished anything in this life worth mentioning who have not had a definite purpose in view, to which every faculty of their mind and body is made to bend. People without a purpose abound on every hand, with nothing in appearance to distinguish them from their fellows except a kind of mental or physical inertia or a fickleness of disposition, causing them to flit about from one pursuit to another, as a butterfly does from flower to flower. Their personal lack of purpose may not be apparent to the casual observer, especially if they be sufficiently under the influence of strong-minded, decisive friends, who furnish the purpose for them, and manipulate them as if they were human automatons.

Some people seem to be born with a purpose, or—more properly speaking—with a disposition to form a purpose, and adhere to it. They are not only possessed of energy, but of the power of concentration, the ability to apply themselves to the one particular purpose before them until they succeed.

Lacking a purpose—either innate or acquired—people are apt to drift aimlessly through life, like an abandoned boat upon the ocean, subject to every wind that blows and every current that flows. With conditions favorable, they may float on indefinitely, even as derelicts at sea have been known to do for years without meeting with any serious obstruction. Their course may be so serene, and so attended with good fortune, that observers may be almost forced to the conclusion that they have a charmed existence. The real test of their constancy and endurance comes to the mechanical derelicts when storms beset them and breakers loom up before them, and to their human prototypes when obstacles are encountered that only a strong mind can cope with, and when no friendly support is at hand, to lean upon. The weak and vacillating then flounder in uncertainty, so lacking in self-confidence as to be absolutely unable to formulate and execute any purposeful plan, while the strong-minded, resolute, self-reliant people carefully lay their plans, and then proceed to fulfill them.

Of course the majority of human derelicts are unwilling to admit that their failure to succeed is due to any fault of theirs. They prefer to believe that they are the victims of chance, or ill-luck, or lack of opportunity. Many of them have no desire to work, and others, if not really lazy, have no pride or interest in the work they do, and are therefore very indifferent workmen, and seldom retain a job long after getting it.