SPORT IN VANCOUVER AND NEWFOUNDLAND

BY

SIR JOHN ROGERS

K.C.M.G., D.S.O., F.R.G.S.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS BY THE AUTHOR

AND REPRODUCTIONS OF PHOTOGRAPHS

LONDON

CHAPMAN AND HALL, Ltd.

1912

The following pages are simply a transcription of my rough diary of two autumn holidays in Vancouver Island and Newfoundland in search of sport—should they prove of any use to those who may follow in my steps, I shall feel amply rewarded.

| BOOK I | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | TO VANCOUVER ISLAND | 1 |

| II | VANCOUVER TO THE CAMPBELL RIVER | 15 |

| III | THE FISH AT THE CAMPBELL RIVER | 29 |

| IV | SPORT AT CAMPBELL RIVER | 39 |

| V | FISHING-TACKLE | 61 |

| VI | TO ALERT BAY | 75 |

| VII | IN THE FOREST | 87 |

| VIII | IN THE WAPITI COUNTRY | 107 |

| IX | OUT OF THE FOREST | 119 |

| X | AFTER GOAT ON THE MAINLAND | 131 |

| BOOK II | ||

| I | TO NEWFOUNDLAND | 157 |

| II | TO LONG HARBOUR | 173 |

| III | TO THE HUNTING GROUNDS | 187 |

| IV | HUNGRY GROVE POND TO SANDY POND | 195 |

| V | TO KOSKĀCODDE | 215 |

| VI | SPORT ON KEPSKAIG | 233 |

| VII | TO THE SHOE HILL COUNTRY | 245 |

| VIII | HOMEWARD BOUND | 257 |

| VANCOUVER | ||

| ORIGINAL DRAWINGS | ||

| To face page | ||

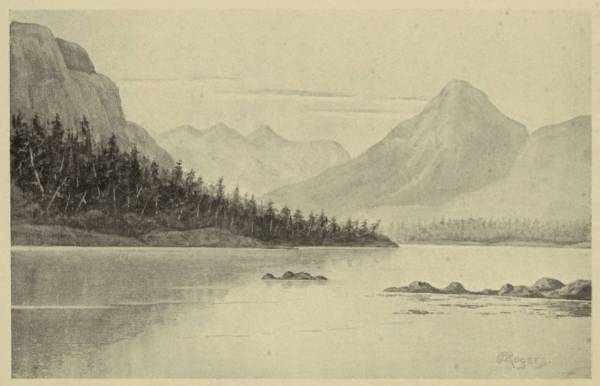

| THE MOUTH OF THE CAMPBELL RIVER | Frontispiece | |

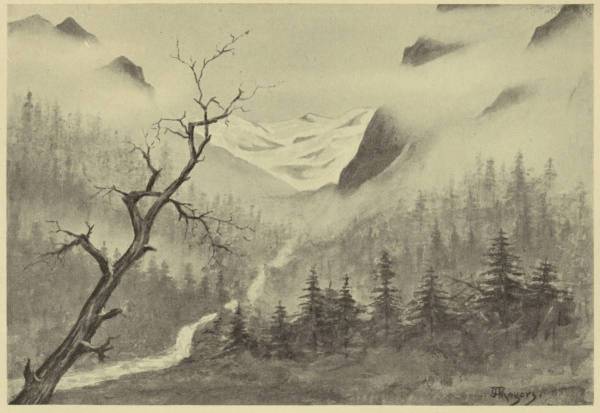

| MORNING MISTS, MT. KINGCOME | 138 | |

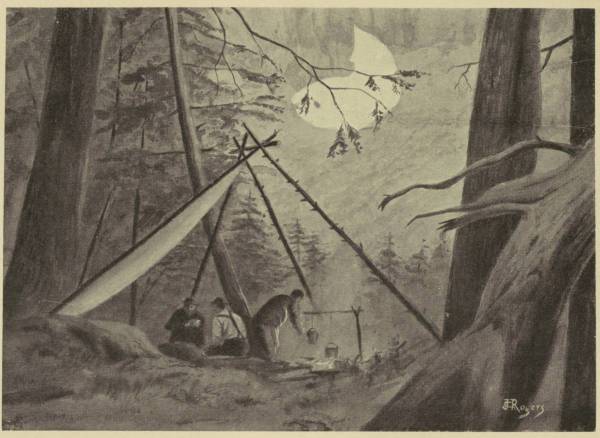

| CAMP ON MT. KINGCOME | 140 | |

| PHOTOS | ||

| THE INDIAN CEMETERY, CAMPBELL RIVER | 41 | |

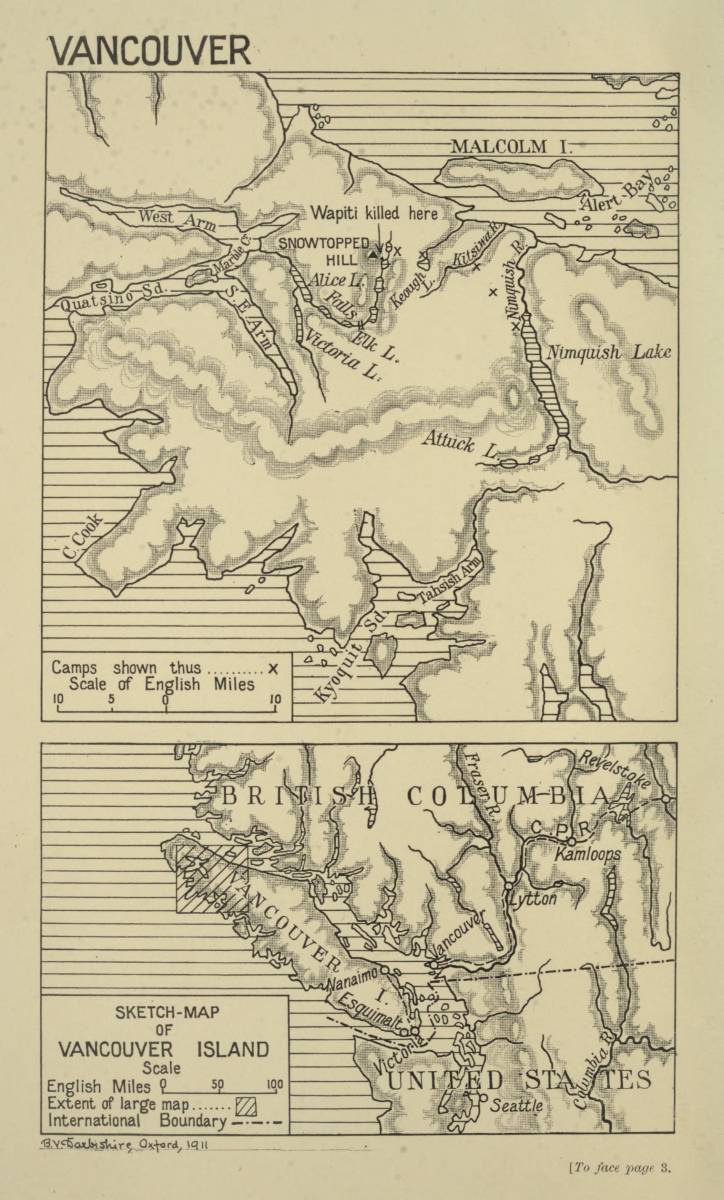

| A MORNING'S CATCH | 41 | |

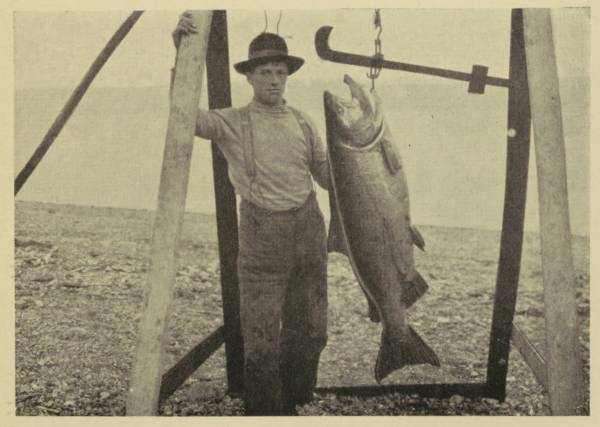

| TWO GOOD FISH | 50 | |

| A 60 LB. FISH | 50 | |

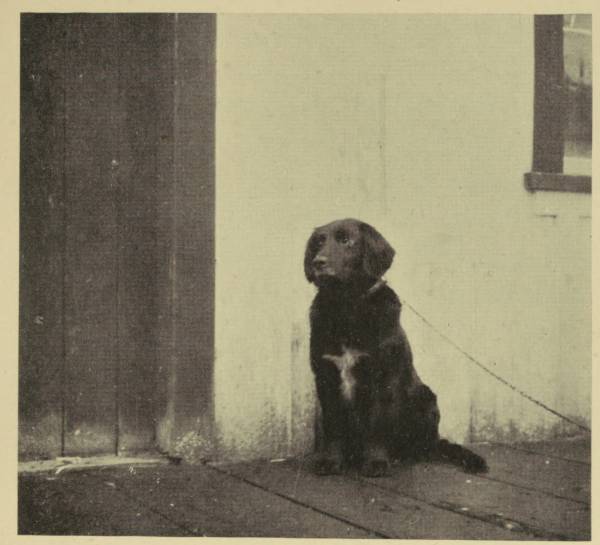

| "DICK" | 80 | |

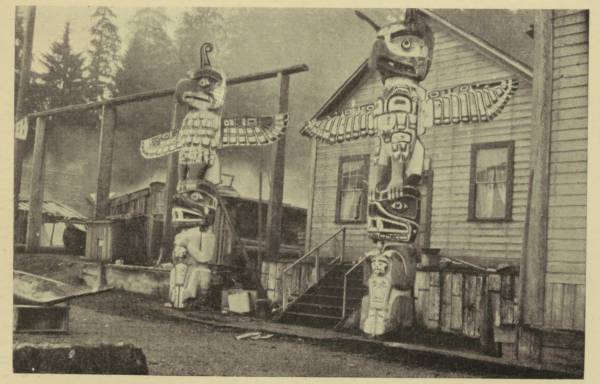

| TOTEM POLES, ALERT BAY | 80 | |

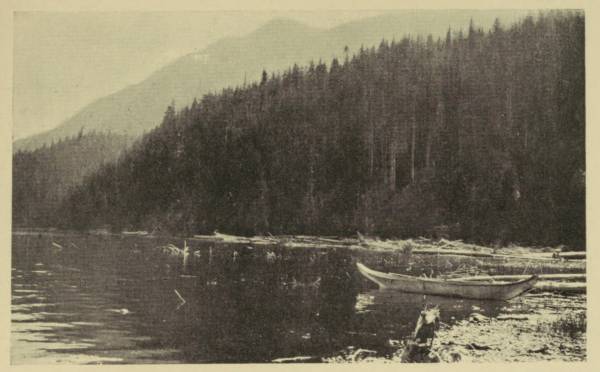

| THE HEAD OF NIMQUISH LAKE | 92 | |

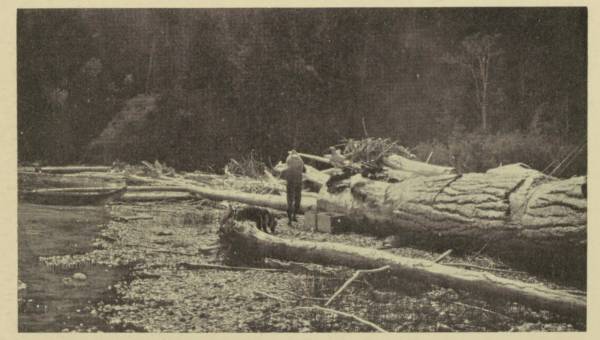

| DRIFTWOOD ON THE BEACH OF LAKE NIMQUISH, "DICK" IN | ||

| THE FOREGROUND | 92 | |

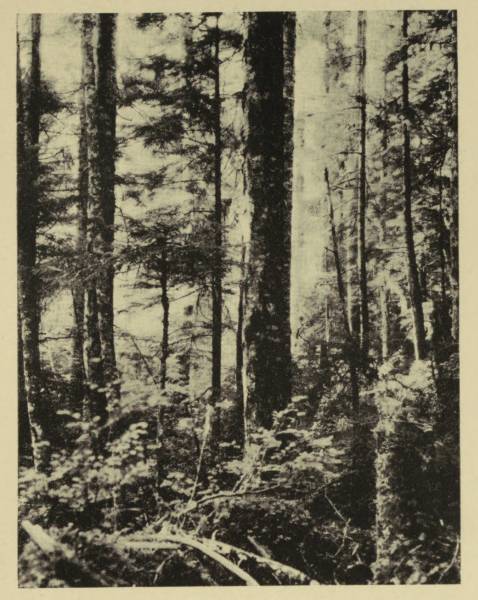

| THE VANCOUVER FOREST, SHOWING UNDERGROWTH THROUGH | ||

| WHICH WE HAD TO MAKE OUR WAY | 110 | |

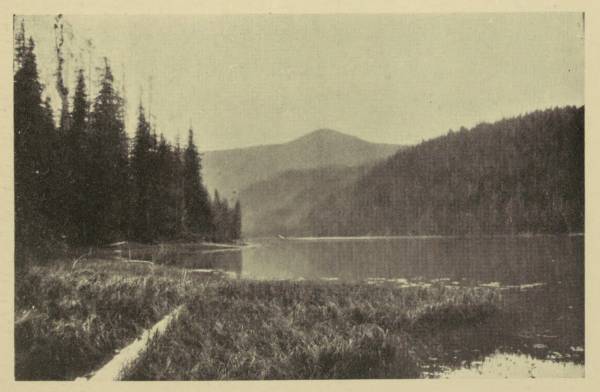

| LAKE NO. 1 | 110 | |

| PACKING OUT | 121 | |

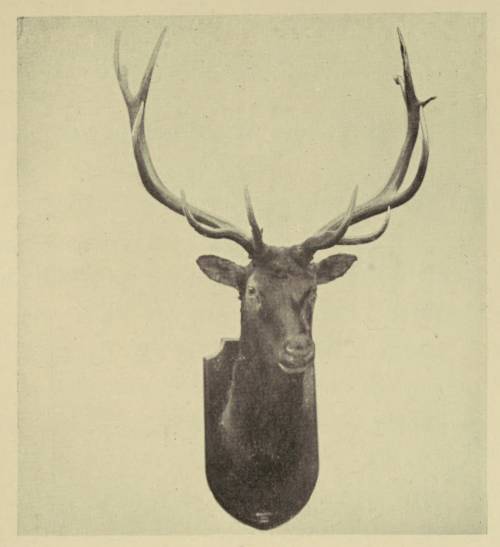

| THE WAPITI, 13 POINTS | 126 | |

| THE SHORE OF LAKE NIMQUISH | 126 | |

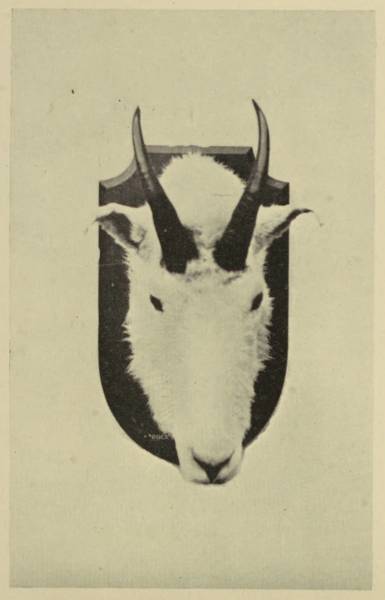

| A ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT | 141 | |

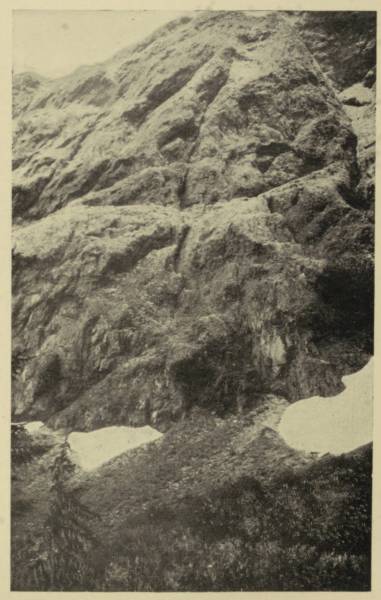

| THE GOAT COUNTRY | 141 | |

| NEWFOUNDLAND[xii] | ||

| ORIGINAL DRAWINGS | ||

| To face page | ||

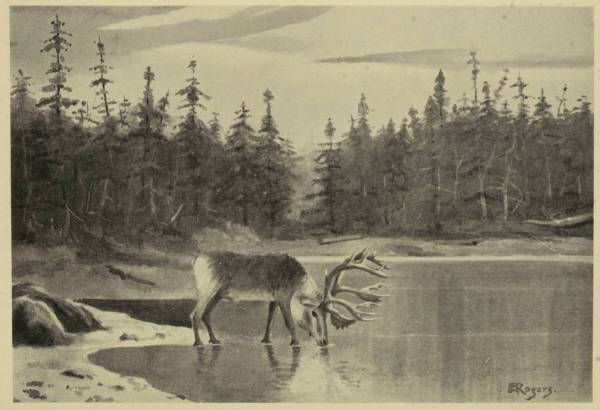

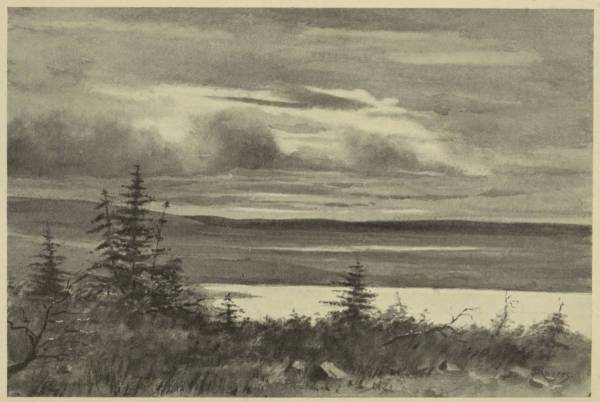

| NOT GOOD ENOUGH | 159 | |

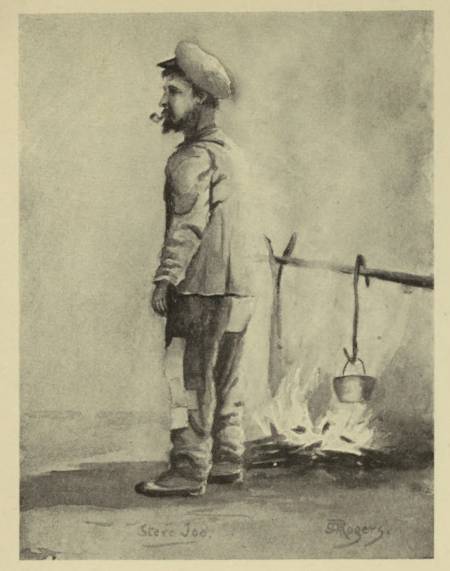

| STEVE JOE DRIES HIMSELF | 226 | |

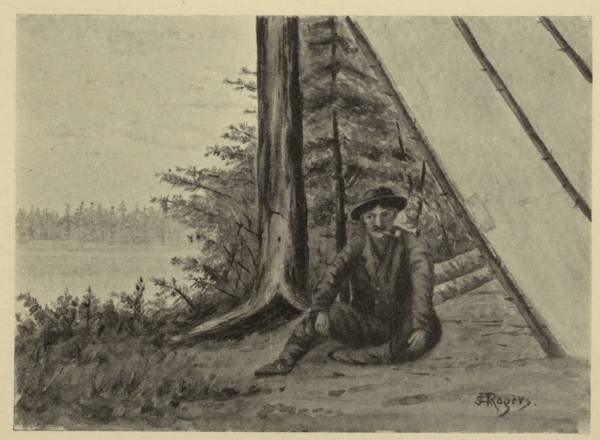

| STEVE BERNARD IN CAMP | 226 | |

| THE CLEARING OF THE STORM, SHOE HILL RIDGE | 247 | |

| A VIEW IN LONG HARBOUR | 263 | |

| PHOTOS | ||

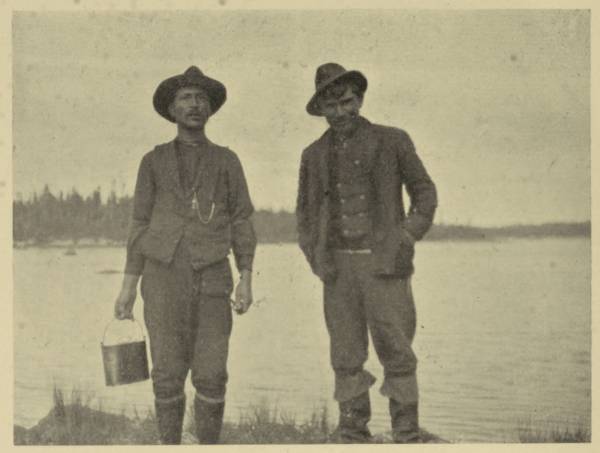

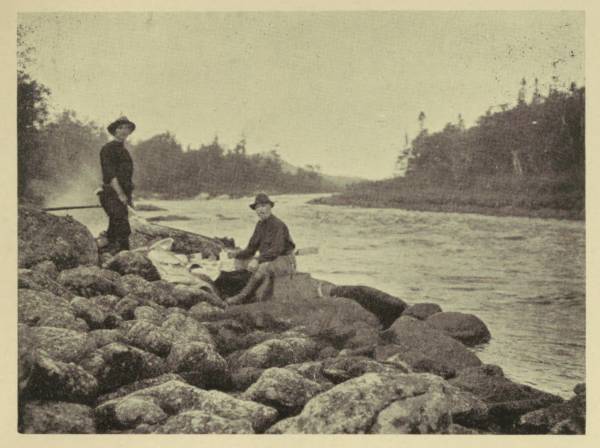

| JOHN DENNY AND STEVE BERNARD | 197 | |

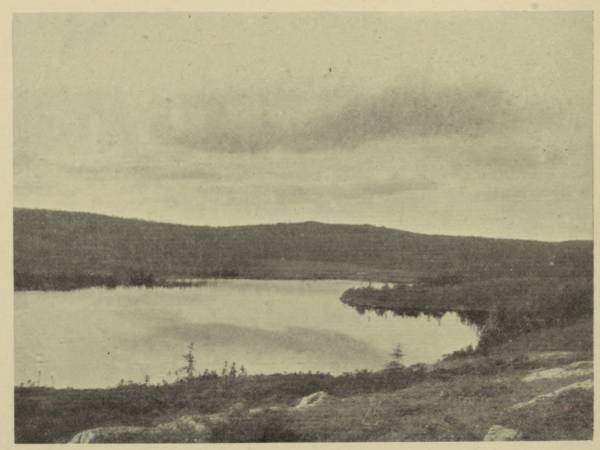

| A NEWFOUNDLAND POND | 197 | |

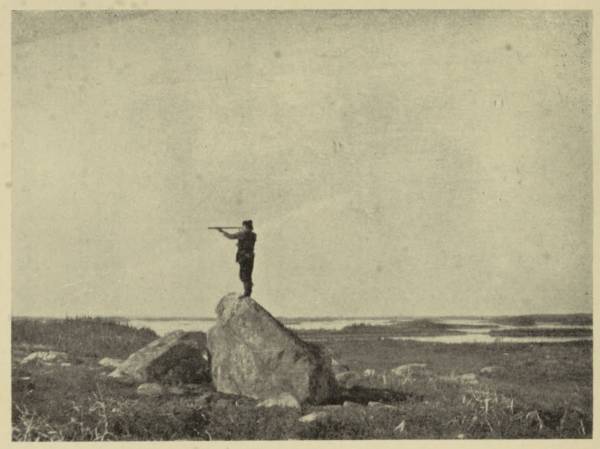

| STEVE SPYING, SANDY POND | 217 | |

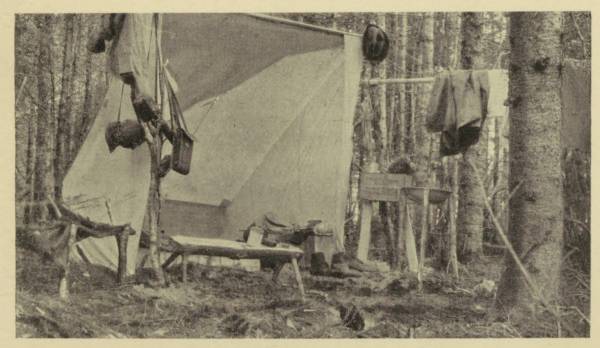

| CAMP, WEST END SANDY POND | 217 | |

| THE THREE-HORNED STAG | 225 | |

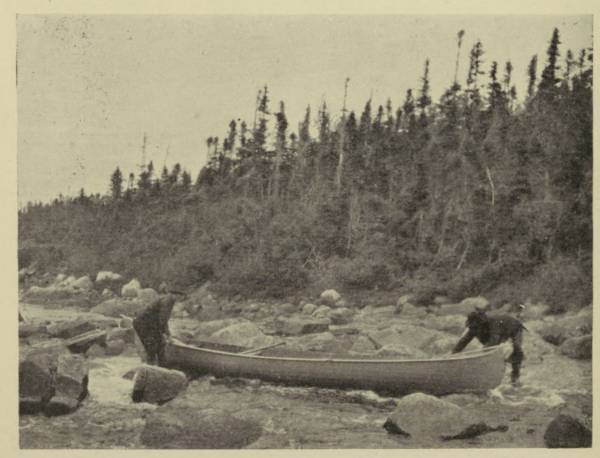

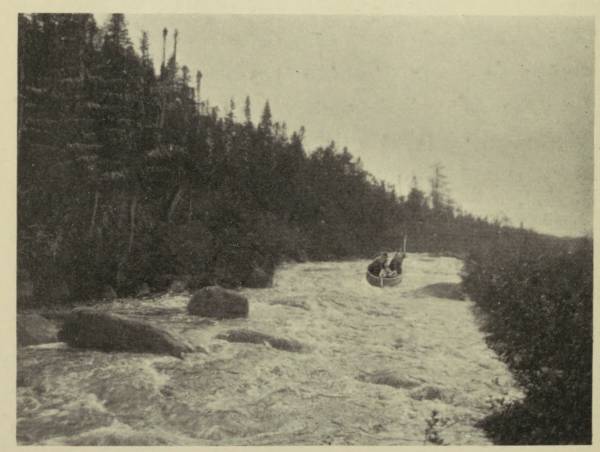

| "BAD WATER" | 225 | |

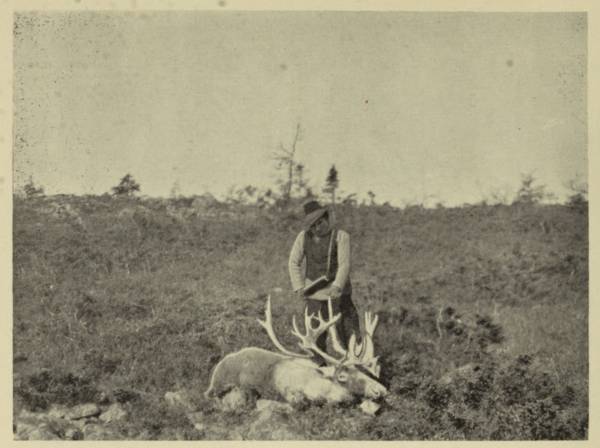

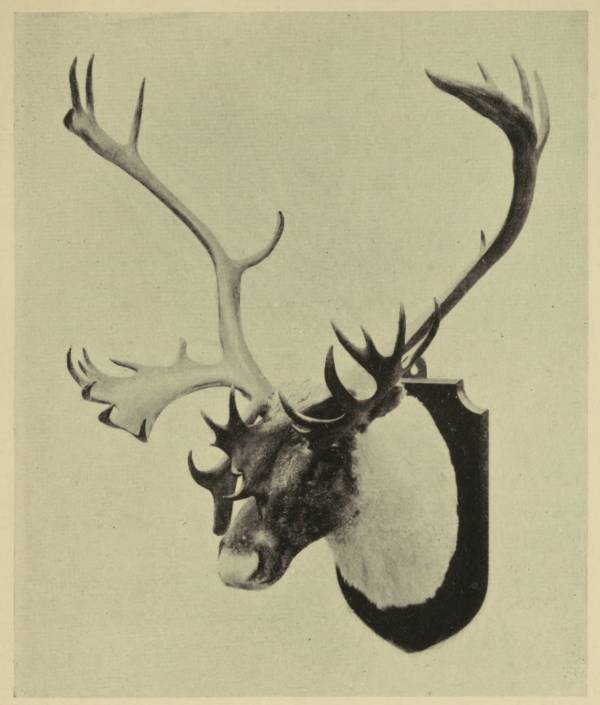

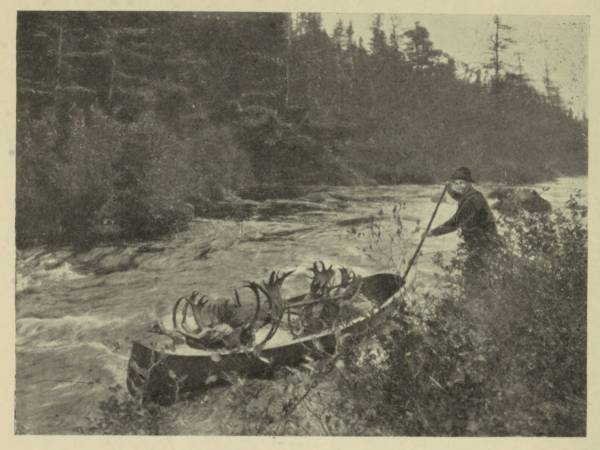

| A THIRTY-FOUR POINT CARIBOU | 238 | |

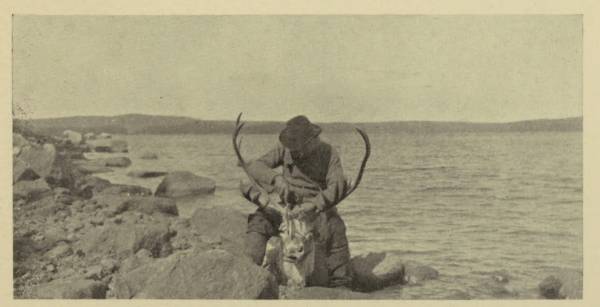

| STEVE SKINNING THE HEAD OF THE THIRTY-FOUR POINTER | 238 | |

| LUNCH ON THE BAIE DU NORD RIVER | 256 | |

| MY CAMP, SHOE HILL DROKE | 256 | |

| UP THE TWO-MILE BROOK, HOMEWARD BOUND | 261 | |

| A BROOK IN FLOOD | 261 | |

| MAPS | ||

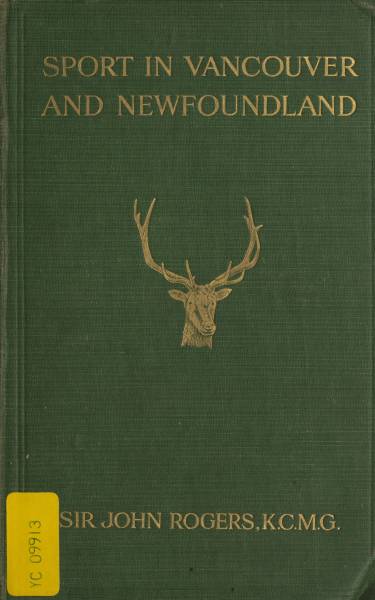

| SKETCH MAP OF VANCOUVER ISLAND | 3 | |

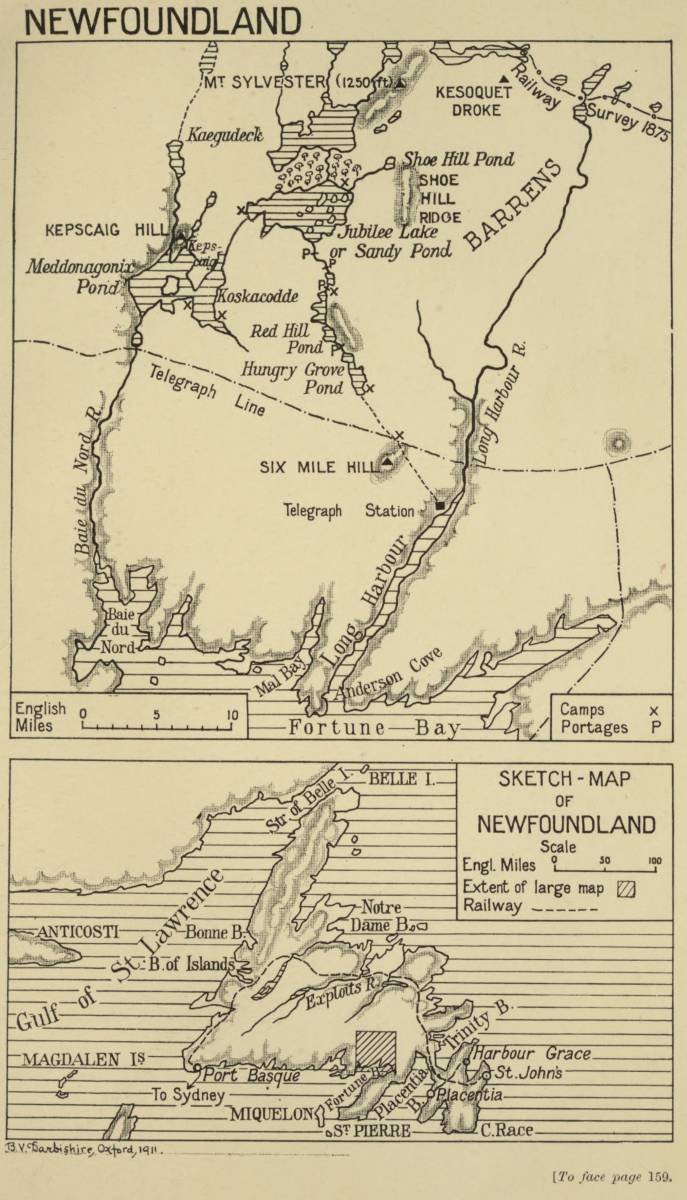

| SKETCH MAP OF NEWFOUNDLAND | 159 | |

From the day I read in the Field Sir Richard Musgrave's article, "A seventy-pound salmon with rod and line," and located the river as the Campbell River, I determined that should the opportunity arise, I, too, would try my luck in those waters.

Subsequent articles in the Field, which appeared from time to time, only increased my desire, and the summer of 1908 found me in a position to start on the trip to which I had so long looked forward.

Living in Egypt, the land of eternal glare and sunshine, I counted the days till I could rest my eyes on the ever-green forests of Vancouver Island.

My intention was to arrive in Vancouver about the end of July, spend the month of August, when the great tyee salmon run, at the Campbell River, and pass September, when the shooting season begins, in hunting for wapiti in the primeval forests which clothe the north of Vancouver Island.

I also hoped, should time permit, to have a try for a Rocky Mountain goat, and possibly a bear on the Mainland.

I sailed from Southampton on July 10, on the Deutschland, the magnificent steamer of the Hamburg-American Line, and never did I travel in greater luxury.

The voyage across the Atlantic is always dull and monotonous; it was therefore with great relief that, having passed Sandy Hook in the early morning, I found myself approaching New York on the 16th.

Here I was to have a new experience.

I am, I hope, a modest man, and never dreamt that I was worthy of becoming the prey of the American interviewer.

The fact of being a Pasha in Egypt, a rank which I attained when serving in the Egyptian Army, was my undoing.

A kind German friend who had used his good offices on my behalf with the Board of the Hamburg-American Line, gave the show away, for I found myself on the printed passenger list figuring as Sir John Rogers Pasha.

To the American interviewer, a Pasha was, I presume, a novelty, and the opportunity of torturing one not to be forgone, for as soon as we came alongside the quay at Hoboken, a[5] pleasant and well-spoken individual came up to me and, raising his hat, remarked, "The Pasha I believe. Welcome to America." I then realized what I was in for.

Had I been a witness in the box, I could not have undergone a more merciless cross-examination. It was almost on a par with a declaration I had to make for the Immigration Authorities—giving my age, where I was born, who were my father and mother, when did they die, what was the colour of my hair and eyes, and lastly, had I ever been in prison, and if so, for what offence?

I really think New York might spare its visitors this ordeal.

Wriggle as I could, my interviewer was determined to obtain copy, and though I insisted that the title of "Pasha" had been entered on the passenger list by mistake, and that it was one not intended for exportation, he was not to be satisfied.

Giving as few details as possible as to how I had obtained my exalted title, I eventually shook off my persecutor. No sooner had I moved a few steps away, than if possible a more plausible person expressed the great pleasure it gave him to welcome me to New York, and endeavoured to impress on me that it was a duty I owed to myself and to the[6] American nation, not only to explain what a "Pasha" was and how I became a Pasha, but also to allow my photograph to be taken, which he guaranteed would appear the following day in his paper—naturally the leading journal of New York.

On my point-blank refusal to accord any more interviewers an audience or to be immortalized in his paper, he sadly expressed his astonishment that I should refuse the celebrity he wished to confer on me.

Had not Mr. Kingdon Gould allowed himself to be photographed?—then why not I?

Other interviewers gave me up as a bad job, but just before landing I was leaning over the side of the steamer when some one shouted, "I have got you!" and I saw that one of my persecutors had taken a snapshot, which I am glad to say must have been a failure, for I did not appear in the New York papers the next day.

I acknowledge that one of my interviewers to whom I had refused any information heaped coals of fire on my head, by rendering me valuable assistance in getting my luggage through the Customs.

I had often heard of the difficulties of the New York Customs, but I must say I never met with greater civility, and there was no[7] delay in passing all my baggage, fishing-rods, guns, rifles, no duty being charged.

New York possessed few attractions for me, and the call of the Campbell River was strong—so July 17th found me starting for Montreal, where I arrived the same night and put up at the excellent Windsor Hotel.

Only a top sleeping berth on the Trans-Continental Express was available for the following night, and, as I desired a section—that is two berths, upper and lower—I had to wait till the evening of Sunday, the 19th, before I could start for Vancouver.

Leaving Montreal at 10.15 p.m., I arrived at Vancouver about noon on the 24th, having travelled straight through.

The Canadian Pacific Railway is probably the most extensively advertised line in the world. I cannot say it complied with modern requirements as regards convenience and comfort.

Every one knows the much-vaunted Pullman Car system of America—men and women in the same carriage, the only privacy being offered by drawing the curtains across the berths which are arranged in two long rows on either side of the car.

If you have a section of two berths, which is essential to comfort, you can stand upright[8] in the lower berth to dress and undress, and put away your clothes where you can.

If you have only a single berth, you have to dress and undress as best you can, sitting in your berth.

On my first trip to Canada, I was only going as far as Mattawa, one night in the train, so contented myself with a single lower berth.

The upper berth was occupied by a very stout lady, who in descending in the morning, gave me an exhibition of understandings as unexpected by me as it was unintentional on her part.

The real advantage of a section, in taking the long Trans-Continental journey, is that when the berths are put up in the day-time, one has a nice compartment to oneself; that is, if the black porter does not condescend sometimes to occupy one of the seats, and only to move, on being politely requested to do so.

The sporting pamphlets of the Canadian Pacific Railway make a sportsman's mouth water. Here we have the paradise of the fisherman—there the Mecca of the sportsman.

It was certainly then disappointing, to say the least of it, to find in the Restaurant Car, that though passing through the paradise of the fisherman, two days out from Montreal, we were eating stale mackerel, and on the return[9] journey when the sporting season was in full swing and duck and prairie hens were being brought in abundance to the car for sale—they were only purchased by the black porters for re-sale at Montreal at a handsome profit. None of them appeared at our table.

The food was indifferent and dear. Everything was "à la carte," and to dine moderately cost 1½ to 2 dollars, while a tiny glass of whisky, served in a specially constructed bottle of infinitesimal proportions, was charged at an exorbitant price.

Food in the car, without wine, beer or spirits, may be put down at 5 to 6 dollars a day, and I would recommend any one making the trip to stow away a bottle of good whisky in his suit-case, from which to fill his own flask for meals.

Travelling for six days and five nights continuously, one would have thought that some simple bathing arrangements would have been provided. A douche even would have been welcome. The lavatory and smoking-room were one and the same—five to six persons could find sitting accommodation, and four basins had to meet the washing requirements of the entire car.

I do not wish to be over critical, but I am glad to say I have met many Canadians who agree with me that the arrangements for the[10] comfort of the passengers on the Canadian Pacific Railway are capable of improvement.

Very different, I was told, was the comfort to be found on the American Trans-Continental Line from Seattle via Chicago to New York. The train is provided with a bathroom, library and a barber's shop, while an American friend who recommended me to return by the American Express, assured me that the food left nothing to be desired.

When competition arises between the two Trans-Continental lines in Canada, the second of which is now being constructed, some improvements may be hoped for.

The scenery of the Rocky Mountains has so often been described, that I will not inflict my impressions at any length on my readers. It is certainly fine, but no part of it can in my opinion compare with that of the line from Lucerne to Milan via the St. Gothard, and what a difference in the engineering of the line and the speed of the trains. Accidents by derailing of ballast trains seemed fairly common. We saw one on our way across, and two engines which had toppled over the embankment marked the site of at least one other.

As regards the Rockies, it must be admitted that the effect of their real height is taken[11] away by the gradual rise in level as one crosses the plains.

Calgary, where the mountains are first approached, stands at 3,428 feet above sea-level.

All things come to an end, and the morning of July 24th found us steaming into the city of Vancouver, glad that the weary journey was at last over.

The town of Vancouver is beautifully situated on the Mainland overlooking the Straits of Georgia.

I am glad, after my criticisms of the Canadian Pacific Railway, to testify to the comfort and moderate charges of the Canadian Pacific Railway Hotel at Vancouver.

A charming bedroom with bathroom attached cost only 5 dollars, all meals included. Excellent beer, locally brewed, was cheap, and a bottle of Californian Chianti, quite a drinkable wine, cost only a dollar, so there was nothing to complain of.

My waiter happened to be an Irishman, and he took quite a personal interest in my comfort, whispering into my ear in the most confidential manner the dishes of the day that he recommended as the best.

On a day's acquaintance, claiming me as a countryman, he confided to me his story. His[12] father had been manager of a bank in Ireland, and he was sent abroad to settle in Canada.

Starting on a farm, and, according to his own story, doing well, a fire destroyed his house and farm implements. Drifting through various stages, he arrived at his present position, with which he seemed quite content. He was married, and lived outside the hotel. Fishing was his passion, and every spare moment was devoted to it.

He was really a most entertaining companion, with a keen sense of humour, and he made the meal-time pass very pleasantly, for he never ceased chatting.

A run by steamer to Seattle to see some friends, gave me a glimpse of Victoria and the exquisite scenery of the trip from Vancouver to Seattle.

At Vancouver I had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of Mr. Bryan Williams, the Provincial Game Warden of British Columbia, with whom I had been already in correspondence, and to whom I was indebted for much valuable assistance and advice.

A true sportsman, his heart is in his job, and if he only be given a free hand and adequate funds, the preservation of game in British Columbia will be in safe hands.

The licence, 100 dollars, is not a heavy one,[13] but I think it might with justice be graduated, fixing one sum, say 50 dollars, for Vancouver Island, where only wapiti, an occasional bear and deer are found, and imposing the higher licence for the Mainland, to include moose, mountain sheep, goat, caribou and grizzly bear.

One would have thought that in the city of Vancouver, the centre of a great angling country, every requirement of the fisherman would have been found. The contrary was the case.

Fortunately I had brought my own fishing-tackle, for in the best sporting shop in the town I could not obtain a suitable spare fishing-line.

Rods, reels, lines, flies and baits were inferior in workmanship as compared to what one is accustomed at home.

I therefore strongly recommend any fisherman to bring all his tackle from home. In the case of rods, reels and lines, New York may have better, as I shall show when I come to discuss the question of tackle later on.

From the manager of the Bank of Montreal, to whom I had a letter of introduction, I met with great courtesy financially as well as socially, and I became free of the excellent Vancouver Club, so charmingly situated, and only regretted that my short stay prevented my availing myself more of its hospitality.

The morning of July 29th found me on board the Queen City, the small but most comfortable steamer of the Canadian Pacific Railway running north to the Campbell River and beyond.

The Captain was a delightful companion, patriotic to a degree, and regretting what he considered the neglect shown by the Old Country to the Dominion of Canada, when American and Canadian interests were at issue.

The steamer was well found and well managed, while the Captain's skill in approaching our various stopping-places, often dangerous coves with no lights, at any time of the night and in any weather, was to me a continual source of admiration. I travelled with him three times, and never wish for a more charming host or a Captain that inspired more confidence as a navigator.

We arrived at the Campbell River Pier at the unearthly hour of 1 a.m. The proprietor,[18] however, was on the pier waiting with lanterns to show us the way up to the Willows Hotel, where I was to spend a happy month.

The Willows Hotel, beautifully situated on the Valdez Straits within a few yards of the sea, is all that a sportsman could desire. Clean, well-furnished bedrooms, a bathroom and quite a decent table, all for the moderate sum of 2 dollars a day.

The proprietor did not quite realize the fact that the majority of the guests came for the fishing, and not for the food.

The lady who directed the establishment seemed to think the latter the more important.

The breakfast bell rang at 6 a.m., and breakfast was served from 6 to 8 a.m. Lunch or dinner from 12 to 2 p.m., and supper from 6 to 8 p.m.

Woe betide the guest who broke the rules of the house as regards the hours, for he was expected to lose his meal.

In those glorious autumn evenings when it was light up to 10 o'clock, the manageress forgot that a keen fisherman might stay out till 9 or even 10, if the fish were taking.

Dinner he could not expect, but a cold supper, if ordered beforehand, might have been laid out in the dining-room. Nor could attendance be looked for; servants were few and[19] overworked, and it was but natural they should like to go to bed at 10 o'clock, or be free to wander in the woods or along the foreshore with the special young man of the moment.

By making love to the manageress and the Chinese cook, I generally succeeded in finding something to eat if I was late, but I often had to forage for myself in the kitchen, and on one occasion came back to find a plate of very indifferent sandwiches laid out for supper.

Morning tea in one's bedroom was prohibited. I should therefore advise any one addicted to the habit of early morning tea, to provide himself with a "Thermos" bottle, and fill it overnight—besides which, if very enthusiastic, a start might sometimes be made at 4 a.m., when a cup of hot tea and a biscuit make all the difference to one's feelings of comfort.

The hotel was a strange mixture of civilization and discomfort.

We had written menus of which I give a specimen below, but I had to grease my own boots and wash my own clothes, until I found an Indian squaw in the adjoining village who for an exorbitant charge relieved me of my washing, though I greased my boots till the end of my stay.

The drawback to the hotel was the logging camp in the neighbourhood.

The bar of the hotel was about fifty yards from the hotel itself, in a separate building, and on Saturday night many of the loggers came dropping in to waste the earnings of the week. Drunkenness on these occasions was far too common, and till the small hours of the morning the sound of revelry from the bar was not conducive to a good night's rest.

Some of the characters who frequented the bar were weird in the extreme, and when fairly "full"—as the local expression was—the hotel was not inviolate to them. One who particularly interested me might have been taken out of one of Fenimore Cooper's novels. My acquaintance with him was made on the hotel verandah. With a friendly feeling born of much whisky, he placed his arm on my shoulder, and assured me that although if he had his rights he would be a Lord, he did not disdain the acquaintanceship of a commoner like myself; in fact, that he had seldom seen a man to whom he had taken such a fancy, or with whom he would more willingly tramp the woods, if I would only give him the pleasure of my company in his trapper's hut some few miles inland. His suggestion that our friendship should be cemented by an adjournment to the bar did not meet with the ready acceptance he expected, which evidently disappointed[22] him, for he could not grasp the fact that any one living could refuse a drink.

Poor "Lord B.," as he was called, was only his own enemy. As I always addressed him "My Lord," which he took quite seriously, we became quite pals.

A trapper and prospector by profession, he had a fair education, and when sober was a shrewd man of the local world, which confined itself to prospecting for minerals and cruising timber claims.

Persistently drunk for two or three days at a time, he would suddenly sober down, put a pack on his back which few men could carry, and disappear into the woods to his lonely log cabin, only to return in a few days ready for a fresh spree. At least, this was his life while I stayed at the hotel, for in one month he appeared three times.

No doubt during the winter, when occupied with his traps, he could neither afford the time nor the money for an hotel visit.

He was wizened in appearance and lightly built, but as hard as nails. Dishevelled to look at when on the spree, as soon as it was all over he became a different character, appearing in neat, clean clothes, and full of reminiscences of backwoods life. He was always a subject of interest to me, and, poor fellow,[23] like many others on the west coast, only his own enemy.

Another frequenter of the bar had been on the Variety stage in London, and his step-dancing when fairly primed with whisky was something to see and remember.

We were a pleasant party at the hotel. Some came only for the fishing, some en route for Alaska or elsewhere on the Mainland for the coming shooting season, others returning from sporting expeditions in far lands.

We had J. G. Millais, the well-known naturalist and author of the most charming book ever written on Newfoundland, bound for Alaska in search of record moose and caribou.

Colonel Atherton, who, starting from India, had recently crossed Central Asia and obtained some splendid trophies, the photographs of which made us all envious.

F. Grey Griswold from New York, of tarpon fame, come to try his luck with the tyee salmon, and good luck it was, which such a good sportsman deserved.

Mr. Daggett, an enthusiastic angler from Salt Lake City, who took plaster casts of his fish, and was apparently an old habitué of the hotel.

Powell and a young undergraduate friend Stern, also bound for Alaska, just starting on[24] the glorious life of sport, with little experience—that was to come—but who with the tyee salmon were as good as any of us, and whose keenness spoke well for the future.

It was curious that in such a small community three of us, the Colonel, Millais and I, had fished in Iceland, and many interesting chats we had about the sport in that fascinating island.

As the sun went down, the boats began to come in, and all interest was concentrated on the beach, where the fish were brought to be weighed on the very inaccurate steelyard set up on a shaky tripod by the hotel proprietor.

Any one reading Sir Richard Musgrave's article in the Field, would be led to believe that the fishing was in the Campbell River itself.

Whatever it may have been in his time, the river is now practically useless from the fisherman's point of view. This is due to the logging camp in the vicinity, for the river for about a mile from its mouth is practically blocked with great rafts of enormous logs. The logs are discharged into the river with a roar and a crash, enough to frighten every fish out of the water; the rafts when formed are towed down to Vancouver.

The river no doubt was a fine one till the[25] logging business was established, and it is possible that late in the autumn fish may run up to spawn—but during the entire month of August, I personally never saw a salmon of any kind in the river itself.

Flowing out of the Campbell lake a few miles away, its course is very rapid, and it falls into the sea about one and a half miles north of the hotel.

The falls, impassable for fish, can be visited in a long day's walk from the hotel. The distance is not great, but the impenetrable character of the Vancouver forest makes the walk a very fatiguing one. It is most regrettable that no track has been cleared along the banks, to enable the water to be fished and to give access to the falls, which I am told are very beautiful.

I endeavoured to reach them by the river, but spent most of the day up to my waist in water, hauling my boat through the rapids, and then only got half-way and saw no fish.

Below the falls, there is a fine deep pool in which Mr. Layard, who described his trip in the Field, states he saw the great tyee salmon "in droves." He does not say at what time of the year he visited the falls or whether the logging camp then existed. It must have been late in the season, for he describes the swarms[26] of duck and wild geese, the seals that were a perfect plague, the sea-lions that were seen several times, and the bear, panther (cougar), deer and willow grouse in the immediate vicinity of the hotel.

I can only give my personal experiences during the month of August.

Forgetting that the shooting season did not begin till September 1st, I took with me 300 cartridges and never fired a shot, nor did I see anything to shoot at. A few duck were occasionally seen flying down the Straits between Vancouver and Valdez Island, but the seals, sea-lions and other game described by Mr. Layard were conspicuous by their absence in the month of August. No doubt later on, in September and October, different conditions may prevail, but August is the month par excellence for the fisherman and he may leave his gun behind.

The tide runs up the river for about 800 yards from the mouth, where there was some water free from logs and rafts. Some good sport with the cut-throat trout was to be had, more especially at spring tides.

My best catch was fourteen weighing 16½ lb.

The water was intensely clear; careful wading, long casting and very fine tackle were necessary to obtain any sport.

The cut-throat trout appeared to me to resemble the sea trout in its habits, hanging about the mouth of the river and running up with the tide, many falling back on the turn of the tide, but a certain number running up and remaining in the upper reaches.

The largest I killed, 5 lb., was immediately in front of the hotel, in the sea itself, one and a half miles from the river, and he took a spoon intended for a tyee salmon.

They were most sporting fish and were excellent eating, differing in this respect from the salmon. I only regretted I did not give more time to them, but we all suffered from the same disease, that desire to get the 70 lb. fish, or at least something bigger than any yet brought to the gaff.

I started with the best intentions, and talked over with Mr. Williams at Vancouver the possibility of inducing the tyee salmon to take the fly, denouncing, as all true fishermen must do, the monotony of trolling for big fish with a colossal spoon and a six-ounce lead, which takes away half the pleasure of the sport.

All the same I found myself sacrificing my principles to the hope of the monster fish which never came, but was always a possibility.

The Straits between Vancouver Island and Valdez Island are about two miles broad, and[28] through them runs a tide against which it is almost impossible to row a boat.

The favourite fishing-ground was about 300 yards north and south of the mouth of the river, and tides had to be seriously considered in getting on to the water.

Another good spot neglected by most of us, except the Salt Lake City angler, was just opposite the Indian Cemetery about a mile from the hotel.

Here, in one morning, I killed three large fish on my way back to the hotel from the more favourite ground which I had fished all the morning in vain.

South of the hotel and down to the Cape Mudge Lighthouse, about four miles away, a few tyee salmon were to be met with, but in the water all along Valdez Island and near the lighthouse, the cohoe salmon were in abundance, and it was the favourite spot for the Indian fishermen who were fishing for the salmon cannery at Quatiaski.

Different names have been given by different sportsmen to the salmon found on the Pacific Coast.

Sir R. Musgrave talks of spring salmon of 53 lb. and silver salmon of 16 and 8 lb.

I inquired carefully from the manager of the Cannery Factory in Quatiaski Cove, and believe the following to be the correct nomenclature.

The tyee or King salmon, running from 28 lb. to 60 and upwards.

The spring salmon, which appeared to me to be the young tyee, having the same relation to the big tyee as the grilse has to the salmon, from 15 to 20 lb.

The cohoe, which run from 7 to 12 lb.; and lastly the blue back, generally termed cohoe, averaging about 6 lb.

These latter most of us called cohoe, and were the fish being caught on my arrival at the hotel.

The run of tyee had not regularly set in, though a few odd ones were being caught.

Later on, when making a trip on the Cannery steamer which collects fish daily from various stations up and down the coast, the manager of the factory, who was on board, pointed out to me amongst the hundreds of fish we collected, the difference between the blue back and the real cohoe.

The former runs much earlier than the latter, and is seldom over 6 lb. in weight; the latter were, he stated, just beginning to run—then the middle of August—and the largest on board weighed 14 lb.

It was not, however, till my return from Vancouver that I came across the volume on Salmon and Trout of the American Sportsman's Library, edited by Caspar Whitman, and there found recorded all that is known about the salmon and trout of the Pacific Coast.

To begin with, the Pacific salmon does not belong to the genus "Salmo," but to the genus "Oncorhynchus," which, according to Messrs. C. H. Townsend and H. W. Smith, the authors of the most interesting chapters on the Pacific salmon in the above-mentioned book, is peculiar to the Pacific Coast.

One peculiarity of the Pacific salmon seems to be that they invariably die after spawning, and never return to the sea.

In the case of the humpback, I saw this for[33] myself later on in the season, when every stream was literally a mass of moving fish all pushing up to the head-waters, and there dying in vast numbers.

The tyee salmon, "Oncorhynchus tschawytscha," has many names. It is known to the Indians as "Chinook," "tyee" and "quinnat," to others as the Columbia salmon, the Sacramento and King salmon.

It appears to range from Monterey Bay, California, as far north as Alaska.

Messrs. Townsend and Smith state that in the Yukon and Norton Sounds it attains a weight of 110 lb., and in the Columbia 80 lb.

The largest I saw caught at Campbell River weighed close on 70 lb. The largest fish brought to the hotel by any of us was about 60 lb.

The blue back salmon, "Oncorhynchus Nerka," is stated by the same authorities to run up to 15 lb., and the average to be under 5 lb.

This would appear from its description to correspond with the fish pointed out to me by the Cannery manager as blue back—though I cannot quite reconcile its other names: red fish, red salmon, Fraser River salmon and Sockeye—for the fishermen at Campbell River spoke of the Sockeye as quite a different fish, running at a different season of the year.

No doubt, however, the scientists are right.[34] I only wish I had known of this valuable book before instead of after my visit.

Another of the "Oncorhynchi" is the humpback, "Oncorhynchus Gorbuscha," averaging about 5 lb.

I only saw one caught on the rod at Campbell River.

At the mouth of the Oyster River, some miles south, I saw them one evening in incredible numbers, and though right in the middle of immense shoals, I could not get them to look at fly or spoon. A few yards up the river they were said sometimes to take the fly.

The silver salmon, "Oncorhynchus Kisutch," known also as "Kisutch," "Skowitz," Hoopid and lastly Cohoe, is stated to attain a weight of 30 lb.—the average weight being about 8 lb. As stated before, the largest I saw was 14 lb. and the largest I caught 12 lb.

The above being the fish I met with at Campbell River, I need not enter into the other varieties. One interesting fact mentioned in the book to which I am indebted for all the above information is that the steel-head salmon is one of the "Salmonidæ." "Salmo Gairdnerii" differs from all other Pacific salmon, in that it alone returns to the sea after spawning, thus following the habits of the true "Salmonidæ."

The only trout I came across at Campbell River or throughout my trip was that known as the cut-throat, so called from the red slash on the throat.

On turning to Mr. Wilson's article on "The Trout of America," I was surprised to find that there were thirteen varieties of this fish, but so far as I could identify those I caught, they must come under the heading of "Salmo Clarkii," the cut-throat or Columbia River trout.

After many inquiries and after having visited the aquarium at New York, I was led to believe that my fish was the "Salmo Clarkii Pleuriticus," but as those I caught had no lateral red band they must have been the "Salmo Clarkii."

The largest I caught weighed 5 lb., and, as I have mentioned before, it was caught in the sea on a large spoon one and a half miles from the river, when trolling for tyee.

The number of fish which frequent the Campbell River waters is almost incredible. When it is realized that between one and two thousand salmon of the various kinds are collected daily by the Cannery launch, and that all these have been caught with rod and hand-line—the great majority with hand-line—some idea may be formed of their numbers.

No one fishing at the Campbell River should miss the trip, which through the courtesy of the manager at Quatiaski Cove is always possible, of going with the Cannery steam-launch on its daily round collecting fish at the various stations, north and south.

Starting from Quatiaski early in the morning, the run is down to Cape Mudge, where perhaps thirty or forty boats, mostly Indian, have been working their hand-lines the evening before. From Cape Mudge up to the Seymour Narrows, about seven miles, many calls are made.

Picturesque Indian camps are numerous all along the shore, and at each of these a stop is made. The canoes come crowding alongside, and the fish are checked as they are thrown into the deep well in the centre of the launch.

Each Indian has a book in which is entered to his credit the number of his fish, and the launch passes on to the next collecting station, to which single canoes from all sides are gathering. On the return the boats of the successful hotel fishermen stop the launch and hand over their catch, for the fish caught are the perquisites of the men who row the boats.

On the day I made the trip we collected about 1,500 salmon.

The business of the Cannery must be a profitable one. So far as I could gather there were[37] but two prices: 50 cents for a tyee, no matter what his weight was, and 10 cents for each smaller fish.

Associated with the Cannery is a general store kept by the Cannery owners, and payment is partly made in goods, so the Cannery has the double profit, first on the fish and then on the goods bartered in exchange.

July 30th I looked forward to as a red-letter day in my life, for was I not to have my first chance for that 70 lb. fish, about which I had dreamt for so many years?

The early morning (we were all up at 6 a.m.) was spent in getting my tackle ship-shape, and, most important of all, in engaging the services of a good boatman—for on his strength and willingness to "buck the tide," as they happily term rowing against the strong tidal currents, depends largely the chance of success.

The man I selected was a fine boatman. Keen on getting fish—jealous of all others of his craft, and with a capacity for bucking about himself, and what he had done and could do, which I have seldom seen equalled.

His command of strong and even highly flavoured language was remarkable, but a little of it went a long way. When I asked his name, he replied, "Every one calls me Billy." No one on the West coast seems to have a surname, so "Billy" he was to me for all my fishing days.

Billy was, I should say, about twenty-three years of age, slightly built, but extraordinarily strong with an oar. His temper was not of the best, and when I lost a fish he always considered that I was to blame, and resented the unfortunate fact as if it were a personal insult to his own powers as a boatman.

I don't believe he ever thought of the Cannery or of the sum which under happier auspices would have stood to his credit. His pay was three dollars a day (12s.) plus the value of the fish. His appetite corresponded with his pay, which was large.

He was willing to row all day long with suitable intervals for his meals—but any attempt to keep him on the water at meal-time was somewhat sulkily resented.

We fished together for some thirty days, more or less harmoniously, and there was only one great explosion which threatened to sever our connection.

Through his gross stupidity my boat, which was being towed behind the Cannery launch, was upset, and I had the pleasure of seeing all my fishing-tackle, fly-books, the companions of years—all my pet flies, spoons, spring balance—sunk in sixty feet of water—£20 worth of tackle gone in a moment.

Fortunately I had taken my rod and camera[43] on board the launch, or they, too, would have been lost.

It was infra dig. that he should express any regret, and very unreasonable from his point of view that I should show any annoyance, which I did in what I considered very moderate terms, considering the provocation.

On landing, he suggested that I did not seem satisfied with him, which was quite true, and that "Joe," a hated rival, was disengaged and available.

I very nearly took him at his word and "fired him out"—but we made it up somehow, and he remained my boatman, though I never quite forgave the loss of so much valuable tackle.

Fortunately I had only a few more fishing days left and had some spare tackle to replace what was gone.

Our opening day was simply glorious, a bright sun and a crispness in the air which made one feel that it was good to be alive.

The scenery was exquisite. The sea calm as a mill-pond, only broken by the oily swirls of the rushing tide, and then there was the possibility of that long-hoped-for big fish, who did not come that day, though every pull from a cohoe might have been him.

Billy was positively polite, as it was his first[44] day. Why many of these West coast men should imagine that politeness means servility, while roughness and rudeness only show equality and independence of character, I never could understand.

It was not long before I was in a fish, but as he was only a 5½ lb. cohoe, he was hauled in with scant ceremony and was soon in the net.

As I shall have something to say about tackle later on, I would only now mention that I was fishing with a fourteen-foot Deeside spinning rod, made by Blacklaw of Kincardine.

I had a large Nottingham reel with 200 yards of tarpon line, purchased in England, not, alas! in New York; a heavy gut trace with large brass swivels which would have frightened any but a Vancouver salmon; a 4 oz. lead, I afterwards came to a 6 oz., and one of Farlow's spoons specially made for the tastes of Vancouver salmon.

My bag that day, fishing morning and evening, was only six cohoe, weighing 3O½ lb. and one cod about 5 lb. I never had a pull from a tyee.

The row home that evening compensated for everything. The sun was setting behind the snow-covered peaks of the Vancouver Mountains, bare and cold below the snow-line, but[45] gradually clothed with foliage down the slopes till the dense pine forest of the plain between the mountains and the sea was reached, from which the evening mists were beginning to rise. In the foreground, the sea, like molten glass, reflected the exquisite colouring of the northern sunset, its surface broken by the eddies of the making tide, or the occasional splash of a leaping salmon. Across the Straits on the Mainland, the tops of the great mountains clothed with eternal snow were lit up a rose-pink by the rays of the setting sun.

I have seldom seen a more beautiful scene, or one which gave such a deep sense of peace. There was a grandeur and immensity about it which satisfied one's very soul, it amply justified the realization of the call of the wild which had brought me so many thousand miles to those distant shores.

The morning of the 31st found me late in starting, as I had to interview Cecil Smith, who was to be my guide, companion and friend on my hunting trip in September.

On that morning, I got only two cohoes of 5½ and 4½ lb., one spring salmon of 9 lb., and as there was evidently no take on, I went up the river for a short time. I saw no salmon, but landed three cut-throat trout weighing 3½ lb., one a good fish of 2 lb.

On the way home to luncheon I killed a 20 lb. fish—a small tyee, and going out for half-an-hour in the evening after dinner lost a heavy fish.

Bad luck as regards the big fish still pursued me. It was true the big run of tyee had not yet begun, but a few were being taken from day to day.

On the morning of August 1st I hooked a heavy fish, but in his second big race, the line slipped over the drum of the Nottingham reel and the inevitable break came.

My catch that day was only three cohoes and three cut-throat trout.

A very high north wind blowing against the tide raised a heavy swell, and fishing was impossible in the afternoon.

August 2nd, I fished all the morning without getting a pull, so decided to try to go up the river to the falls, which attempt, as previously described, was not a success.

Returning to the sea in the afternoon I found Griswold with three fine fish, of 59, 45 and 40 lb. I landed a small tyee of 30½ lb. and four cohoe weighing 20 lb.

On August 3rd, I got my first good fish of 53 lb. and another of 42 lb. The tide was running strong and the 53 lb. fish took out about 120 yards of line, but eventually I got[47] him in hand, when he made two wild runs—threw himself clean out of the water each time and then went to the bottom like a stone and sulked.

It took me just under an hour to kill that fish, and I found that he was foul hooked on the side of the head.

The 42 lb. fish was a lively one and tired himself out by repeated runs—he never got to the bottom and in about fifteen minutes he came to the gaff.

In addition to the two tyee, I had seven cohoe weighing 46½ lb., so luck was beginning to turn.

August 4th was a great day. Four tyee, 45, 44½, 42½ and 35 lb.; one cohoe, 6 lb.; one cut-throat trout, 5 lb., a picture of a fish; one sea trout, 2 lb., and one cod, 5 lb.; all before two o'clock.

There was a big take in the evening, and I missed it by getting out too late.

Griswold had five tyee, the largest 47 lb.; I came in for the tail end of the take and only picked up eight cohoe, weighing 43½ lb., and one spring salmon, 13 lb. Total weight for the day: 240½ lb.

August 5th. I had two tyee, 45 and 37 lb., and sixteen cohoe averaging about 6 lb., and so on day after day, with varying luck and[48] always hoping for that 70 lb. fish which never came.

On August 10th, I got my second biggest fish. The spring tides were racing up and down the Straits and it was impossible to hold a boat, much less row it against the tide.

By this time from a study of the bottom, at low water, I had a fair idea of how the fish ran up and down with the tide. I accordingly anchored my boat off a point I knew the fish were bound to pass. The anchor was fixed on to a log of wood to which the boat was moored by a running knot. It was Billy's duty to cast off the moment I was in a fish.

The greatest race of the tide was at about half flood, and the current was so strong that the heavy spoon and 6 oz. lead were swept away like a cork. Letting out about thirty yards of line and giving Billy the rod to hold, I began casting with the fly, using a fourteen-foot Castleconnell rod, fine tackle and a two-inch silver doctor. I soon had a sea trout, 2½ lb., and two cohoe, besides many rises, and grand sport these fish gave in the racing tide on a light rod.

I had just killed my last fish when the scream of the reel on the rod which Billy was holding told me we were in a big fish. Taking the rod from Billy, I told him to cast off. The fish[49] was racing up with the tide some 150 yards away, but the rope was fouled, or Billy bungled, and the result was a smash.

Hardly had I got out another spoon when I was in another fish. I was evidently lying in their track. This time we got away, and how that fish raced! Before I knew where I was we were up about a mile, being literally towed by him on the flowing tide before I could get him in hand. I eventually killed him, almost opposite the hotel, one and a half miles from where I had hooked him: weight, 59 lb.

In the evening I got two tyee of 47 and 46 lb. The big fish's measurements were: length, 47½ inches; greatest girth, 31½ inches, and girth round the anal fin, 22 inches.

The well-known formula for estimating the weight of a fish from measurement is as follows—

| girth^2 × length | = | weight. |

| —————— | ||

| 800 |

Applying this formula, the weight worked out just 59 lb., which the scales corroborated. The weighing machine, an old rusty steelyard, set up on the beach in front of the hotel, left a good deal to be desired; but I had a spring balance weighing up to 60 lb., which I tested at the local store and found to be quite accurate.

On August 24th heavy clouds were piling up, and a break in the glorious weather we had enjoyed from the beginning of August seemed imminent.

On August 26th, my last day at the hotel, I started to fish in a heavy gale from the south-east, the worst wind one could have in these waters.

Though leaving that night and having all my packing to do, I determined to have one last try for the big fish which had so far evaded me.

There was a heavy sea on and it was almost impossible to hold the boat, but Billy was on his mettle for the last day's fishing and really did wonders.

On the way down to the mouth of the river, I got a 10 lb. cohoe, and on arriving at the best ground I put on a big brass spoon, which Mr. Daggett had kindly lent me, about twice as long as the Farlow spoon. I was letting out the spoon when I got a tremendous pull and a very short run, which apparently took the fish to the bottom or into some kelp. There he remained and simply sulked without taking out a yard of line.

The rod was bent double and I put on all the strain possible, but it was a full three-quarters of an hour before I could see my lead coming up to the surface, and my arms and back were aching. How the rod did not break I cannot[51] understand, for the fish came up gradually from straight under the boat; but at last I had the gaff in the biggest but least sporting fish I had killed during the month. He weighed 59½ lb. at the hotel, having lost a good deal of blood, and must have been over 60 lb. when he came out of the water. The brass spoon was either bitten or broken in half.

Having killed forty-one tyee, fished steadily for a month, and seen most of the fish that were caught, I do not think many fish over 60 lb. are killed. One fish caught by a hand-line and small spoon by a young settler named Pidcock, I weighed, and he must have been close on 70 lb. My spring balance went down with a rush to its limit of 60 lb., and I heard afterwards that when weighed at the Cannery it scaled 68 lb., so when fresh must have been close on 70 lb. This was the biggest fish I saw on the coast.

Farther north there are other fishing grounds well worth a visit, where the fish are said to run up to 100 lb.—such are the Kitimaat River and McCallister's Bay at the entrance to Gardner Canal, about four hundred miles north of Campbell River.

A steamer runs direct to Kitimaat and Hartley Bay once a month. Accommodation[52] can be had at Kitimaat, but a camp is necessary at McCallister's Bay. Fish run as early as May. Campbell River is getting too well known, and there are too many boats on the water.

The following amusing description of an evening's fishing is from the clever pen of J. G. Millais, and was published in Country Life. I venture to reproduce it—

"Amidst gorgeous sunset hues we went to fish the usual beat opposite the Indian village on August 11th. The sun had already set, when of a sudden a suppressed excitement ran through the boats. A fresh run of tyee were in and had begun to take. Three or four Indians were 'fast' at once, and yells for help came down the line. In a moment, while close to the beacon stake at the mouth of the river, Mr. Powell, Sir John Rogers and I were 'into' fish at the same moment.

"Then the circus began. 'Look out there; don't you see I'm fast?' 'Confound you; get up your line, or I'll be over you.' 'Gangway, gangway,' 'Where the devil are you coming to!' 'Mind your oars,' 'He's off to the tide. Hurry' (Mac or Bill, as the case might be); 'row like blazes,' were a few of the cries that broke from excited anglers, while [53]even phlegmatic Indians grinned or yelled 'tyee, tyee' in sympathetic encouragement. We all cleared each other somehow. I do not quite know how. Sir John was whisked straight out to sea, and was a quarter of a mile off in no time. Mr. Powell broke, while my fish, to my horror, went straight for the beacon. I lugged at him to steer clear, and he took the hint so forcibly that he burnt my finger on the line with the rush he made for the deep water. It was like poor Dan Leno's hunting song, 'Away, away and away. I don't know where we're going to, but away and away and away.' We could hear men laughing and joking in the darkness behind, and then in a moment we were out of it all in the silence of the boiling tide. Mac was a good boatman, and the way he followed that tyee in the eight-knot current did him credit. This was the strongest fish I have ever hooked. He seemed to do with us just what he chose, and we, like sheep, had to follow. If he had carried out his first laudable intention of a visit to Queen Charlotte Islands he might have defeated us, but seemingly he altered his plan and made a fierce hundred yards' run for the curl of the current at the mouth of the Campbell River. Here there were nasty lumps of floating kelp, and the two anglers fishing there received our return landwards [54]with shouts of warning. In the gloom I could see by their attitudes that they were intensely interested in our welfare, for the next best thing to playing a fish yourself is to watch another at the game. Then began a series of 'magnificent cruises.' It is part of the interest in salmon-fishing that the fish you have 'on' is infinitely larger than anything previously hooked. Generally it is a pleasant delusion; but sometimes it is true, and then the conflicting emotions of the play and the thrill of subsequent capture are something to live for.

"My fish was, I knew, the biggest I had ever hooked, so one had to follow the same old ways of playing him, coupled with such extra force as that stout tackle warranted. After every great circuit of the boat I resorted to all sorts of devices for tiring my antagonist, but he refused to give in or to allow me to shorten the line. But my fish was as gallant a fighter as ever was hatched, and the better the fighter the quicker he kills himself. Half-an-hour has elapsed and I see the lead six feet up the line for the first time. Soon we shall see back and tail. Yes, there they are, and what a monster. He must be 60 lb. at least. At last he shows side, and that is the beginning of the end. Mac, an indifferent gaffer under the most favourable circumstances, now surpasses himself[55] in the fields of incompetence. He makes one or two feeble shots, and then, getting the gaff well home, attempts to lift the fish as I throw my weight on to the reverse side of the light boat to prevent an upset. He heaves with both hands, and a great head appears, when crack goes the steel, and Mac sits down heavily in the boat, looking supremely foolish. I was not distressed, however, as that brief view of the fish's head had shown me the hook well placed; moreover, I knew that somewhere under the thwarts we possessed a goodly club. Mac, after a few moments' search, produced the truncheon, and, at the first attempt, stunned the salmon with a well-directed blow, and lifting it with his hand drew it into the boat. Ha! this is a fish indeed; one of the best of the season, we flatter ourselves, and 60 lb. for certain. But no; those cruel scales blast our hopes by 3 lb. Still, a fifty-seven-pounder is something to be proud of, and we rowed home that night at peace with the world. This, then, is Campbell River fishing for the great tyee salmon. If you wish to collect records you can do so by sitting all day in your boat for a month and using a tarpon-rod, which kills the biggest fish in two minutes, and a Vom Hofe reel, which carries a drag that would stop a buffalo."

If there are many Indians out the rod has not much chance, for their canoes cross and recross in every direction, and as they fish with a short hand-line, a long line let out from the rod is apt to get fouled.

Fortunately, their favourite ground is by Cape Mudge Lighthouse, where the cohoe abound. I only tried this water once, and was so jostled by Indian canoes that I determined to stick to the tyee and the mouth of the Campbell River.

The large majority of the salmon were really sporting fish. The cohoe had no chance with the strong tackle necessary for the tyee, but still were wonderfully lively, and when caught with light tackle on the fly, gave great sport.

In one respect they were all a hopeless failure—they were quite unfit to eat. Why it should be so I cannot say. Perfect to look at, as good as any Atlantic fish, the flesh was like cotton wool, dry and devoid of all flavour. On the other hand, the cut-throat trout were excellent eating.

During the entire month of August we had little or no rain. The climate was absolutely ideal and the eye never tired of the exquisite scenery, varying in colouring and effect every day.

The row of one and a half miles from the[57] hotel to the best fishing ground, if the tide was not favourable, was a drawback, and personally I should prefer to pitch a camp on one of the many excellent sites at the mouth of the Campbell River, so one would be independent of the hotel hours and meals. When the tide is not favourable, a good plan is to leave the boat at the mouth of the river and walk home along the shore to the hotel for meals.

The fish generally took best at the turn of the tide, and about half water. Many enthusiasts were out at 3 and 4 a.m. and in some cases struck a good rise, but these early mornings without a cup of tea, I fear, did not often appeal to me.

The following table shows my bag day by day—

| Spring | Cut- | Sea | |||||||||

| Date. | Tyee. | Salmon. | Cohoe. | throat. | Trout. | ||||||

| No. | W. | No. | W. | No. | W. | No. | W. | No. | W. | ||

| July | 30 | — | — | — | — | 6 | 30 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 31 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 2 | — | — |

| Aug. | 1 | — | — | — | — | 3 | 15 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 2 | 1 | 31½ | — | — | 4 | 20 | 3 | 2 | — | — |

| " | 3 | 2 | 53 | — | — | 7 | 47½ | — | — | — | — |

| — | 42 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 4 | 4 | 45 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 47½ | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| — | 44½ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | 42½ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | 35 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 5 | 2 | 45 | — | — | 16 | 98 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 37 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 6 | 3 | 45 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 36 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 42½ | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | 40 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Aug.[58] | 8 | 3 | 42 | — | — | 1 | 6 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 41 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 9 | — | — | 1 | 8 | 4 | 24 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 10 | 3 | 58 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | — | — | 1 | 2½ |

| — | 46 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | 47 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 11 | 2 | 47 | — | — | 3 | 16 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 12 | 1 | 45 | 3 | 34 | 2 | 10 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 13 | 1 | 35 | — | — | 4 | 20 | 14 | 16½ | — | — |

| " | 14 | — | — | 1 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 8½ | — | — |

| " | 15 | 1 | 32 | — | — | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | — | — |

| " | 16 | 2 | 37 | — | — | 9 | 56 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 17 | 2 | 46 | — | — | 1 | 7 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 44 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 18 | 3 | 49 | 2 | 21 | 4 | 25 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 48 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| — | 40 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 19 | 2 | 40 | 1 | 21 | 6 | 48 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 20 | — | — | — | — | 4 | 24 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 21 | 2 | 45 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 38 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 43 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 22 | 2 | 45 | — | — | 8 | 49 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 35 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 23 | 2 | 56 | — | — | 16 | 98 | — | — | — | — |

| — | 37 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| " | 24 | 1 | 26 | — | — | 3 | 24 | — | — | — | — |

| " | 25 | — | — | 1 | 21 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| " | 26 | 1 | 60 | — | — | 1 | 10 | — | — | — | — |

| 41 | 1738 | 15 | 274 | 126 | 772 | 37 | 38 | 2 | 4½ | ||

So the last day had come and the fishing was to be a memory of the past. Our pleasant party was broken up—Millais and his young undergraduate friends, Powell and Stern, had gone north to Wrangel to start on their hunting trip in Alaska; Griswold back to New York,[59] planning the construction of a special boat and the adding of the great tuna to his many trophies of big sea fish. Daggett alone remained, seated daily in the comfortable armchair he had rigged up in his boat, still intent on that 70 lb. fish we had all hoped for, but failed to secure.

The pleasant days of friendly intercourse had come to an end. No more the quiet row home in the gloaming after a successful or moderately successful day. No more the nightly gathering on the beach and the weighing of the great fish. The weather itself looked despondent, and was making up its mind to break. The certainty of the past was over, the uncertainty of the future before me, and it was with a sad heart I bade farewell to the Willows Hotel, and to the fishing days that were now no more.

The depressing hour of 1 a.m. found me sitting on the end of the pier waiting for the arrival of the Queen City, which was only an hour late, and once more I was bound for the unknown.

As regards tackle, one rule only must be followed: everything must be of the best, and the best is to be obtained either in England or New York.

The choice of a rod is a difficult matter, and depends altogether on the individual idea of what constitutes sport.

If by sport is meant the taking of the greatest number of fish in the shortest possible time, in fact the making of a record—no rod is necessary. Follow the Indian method of fishing with a strong hand-line and no trace, the spoon being fastened on to the line direct. The moment the fish is on, if a small one, he is hauled hand over hand up to the canoe and jerked in—if a tyee, he is played by hand. I have never seen one allowed to make a race, and when fairly done he is hauled alongside the canoe, the line held short with the left hand, while a sharp blow on the head is administered with a wooden club, and he is then done for and lifted into the boat—no gaff being used.

It is astonishing how quick the Indians are in killing even a large tyee by this method. The hand playing apparently takes all the life out of the fish, and the strong tackle does the rest.

I have seen many white men follow this system—but they were all fishing for business and the Cannery. Only one white man from the hotel fished in this way, and I don't think any of us envied him his so-called sport.

The take comes on quite unexpectedly—boats will be rowing backwards and forwards without a pull. Suddenly the take comes on and nearly every boat may be in a fish. He, therefore, who can kill his fish quickest will make the biggest bag, if record breaking be his object.

I have seen one Indian canoe bring in over one hundred fish in a day's fishing—but is this sport? I think all true fishermen will say it is not.

After the hand-line comes the rod, and again, if the object be to catch as many fish as possible while the take is on, a small tarpon rod with a Vom Hofe multiplying reel and an 18-thread tarpon line, practically unbreakable, may be used.

One American tarpon fisher, Mr. Griswold, a true sportsman too, followed this method and naturally defended it. I do not in any way criticize his methods, I only felt they did not appeal to me. It is true I have seen him kill three fish while I was killing one, but I did not feel at all envious.

Generous to a degree, he more than once offered to fit me out and instruct me in the art of "pumping" fish, but though much tempted, I did not fall. Had I succumbed, I much fear I should have become an ardent advocate of tarpon methods applied to tyee salmon.

On the other hand, to fish for tyee with a highly finished 18-foot split cane, or other make of rod, seemed to me out of place. There were some who did it and gloried in the fact that they had caught a great tyee on an ordinary home salmon rod.

It seemed to me a waste of good material, for the rod was likely to be broken or permanently strained in the process of lifting a great fish from the depths of the sea—for after one or two rushes taking out 100 to 150 yards of line, the tyee will often go straight down to the bottom, stand on his head and sulk, and then you want that power to bring him up which only a very stiff rod possesses.

One of our number who had killed many a salmon at home, fished with an ordinary 18-foot rod. The fish seemed to do what it liked with him, and it generally ended in the rod being lowered till the tip touched the water, and the boat disappearing in tow of the fish, up or down the Straits with the racing tide.

In fact the fish was being played on the line from the reel without the power of a hand-line. To give him the butt would have inevitably resulted in breaking the rod. Yet this good sportsman sometimes got his fish and came back triumphant, having had him on for a couple of hours.

The local rods, whether those to be obtained in Vancouver or at the store on the pier at Campbell River, seemed to me most inferior in quality and workmanship, and the same applies to all other tackle, except possibly the leads, which are too heavy to carry about and which can be purchased locally.

As stated before, I used a three-piece Deeside spinning rod, twelve feet long, built by Blacklaw of Kincardine—but I must confess that twice my tip was broken by the strain of the weight of a big fish which had to be brought up to the gaff from the bottom of the sea.

Many a time was this little rod bent double, till I wondered how it ever bore the strain. On it I had killed all my tyee and most of my cohoe, but it suffered in the process, and the middle and top joints had to be replaced on my return home. If I were going again, I should feel inclined to take a 10-foot rod built on the same lines and of the very best material and workmanship. Such a rod would give more power and stiffness than the 12-foot rod.

Besides the 12-foot rod, I had a 14-foot three-piece Castleconnell rod, an old friend. This I used for fishing for cohoe with the fly, and grand sport they gave in the racing tide on a rod which played its fish right down to the reel. An ordinary 12-foot trout rod for the cut-throat trout completed my rod equipment.

Reels and Lines.—I started with a large Nottingham reel, but soon gave it up. It had the advantage, of course, of not rusting, but the workmanship could not stand the rush of a heavy fish. I lost big fish by the line slipping over the drum and jamming, though I had fixed up the usual guard improvised out of the brass wire handle of a tin can purchased locally. I then came to my largest bronze[68] salmon reel, after which I had no more trouble—though the salt water caused rusting of the screws.

The reel should take 200 yards of tarpon line and be of the very best and strongest make. The Vom Hofe multiplying reels are perfect specimens of workmanship, and the attached leather drag worked by pressure with the thumb is an excellent device. In fact, for the big fish, from tyee to tarpon, I think the American tackle makers beat us as regards reels and lines.

I purchased two tarpon lines in London; who the maker was I cannot say. One did good service, the other seemed of inferior quality, for it broke without any special reason.

I should recommend 200 yards of 18 or 21 Vom Hofe tarpon line, which now can be purchased in England at Messrs. Farlow & Son's, or in New York.

One great advantage of this line is that it need neither be washed in fresh water after use in the sea nor dried. It can remain on the reel wet without rotting.

Gaff.—Farlow makes a specially strong gaff lashed into a long ash or hazel handle. I found this quite satisfactory. On the other hand, the American fishermen use quite a short gaff,[69] but fishing with a six or seven foot tarpon rod they can bring the fish much closer up to the side of the boat.

A good strong landing net capable of taking a fish up of eight or ten pounds is most useful, and saves gaffing the smaller salmon.

Flies.—I started with the idea that the ordinary trout fly on No. 11 or 13 hook should be as good in Vancouver as it was in Scotland. I had very soon to acknowledge my mistake—the trout preferred a small salmon fly on No. 8 hook; silver grey, silver doctor, Wilkinson and Jock Scott, I found the best patterns.

The cohoe took a 2-inch silver doctor and rose steadily to the fly.

Spoons and Minnows.—Spoons can be obtained locally, either in Vancouver or in the Campbell River Store, but I should recommend their being purchased in England. The spoon specially made by Farlow is three inches long, silver on both sides, with a hook attached to the end of the spoon by a strong wire loop.

Local tastes varied, and in the local store there were many varieties of spoons. One year dull lead spoons were supposed to be most killing—another year it would be brass. Each fisherman had his special fancy.

Mr. Griswold had a silver spoon invented by a friend of his, or himself, for which a patent was about to be applied. He naturally, therefore, did not wish to give away the secret. It certainly was a most killing bait, and Mr. Griswold, between his special spoon and his tarpon methods, killed more fish than any of us for the time he remained at the Campbell River.

He most generously lent me one of his pet spoons on a day he was hauling in fish and I was getting nothing. I was promptly in a big fish which broke me, owing to the line jamming round the Nottingham reel, and away went the patent spoon. I did not feel justified in examining the spoon too closely or taking a drawing of it. It seemed longer than the Farlow spoon. The hook was suspended by a chain and the bait seemed to wobble rather than spin. The material was metal with bright silver plating.

An ordinary large-sized silver Devon Minnow spun from the boat, or at Cape Mudge from the shore, will take cohoe, and good sport can be obtained in this way.

A Tacomah spoon is deadly for cut-throat trout, but I preferred the fly.

Traces.—I took out some specially strong[71] gut spinning traces made by Farlow, but I do not think any traces are necessary. The line is quite as invisible as the trace, and a few feet can be made into a trace by fixing two or three swivels—bronze, if possible, instead of bright brass—about two feet apart.

For fly fishing, good stout loch casting lines which will land a five or seven pound fish are sufficient. Very fine trout casts are unnecessary, except for trout in the river.

Leads.—These can be purchased locally, and one is saved the trouble of adding to the weight of baggage.

The method of fastening the lead on to the line all depends on whether it is decided to lose the lead when the fish is hooked or to fix it permanently on the line. A six-ounce lead when the fish is being played takes away considerably from the pleasure, owing to the dead weight on the rod. On the other hand, if it be decided to lose the lead each time a fish is hooked, a couple of hundred leads may be required.

In the former case, two methods can be adopted: loop up the line about twenty feet from the spoon with a piece of thread, on which is hung the lead; when the strike comes the thread is broken and the lead slips off—or, as[72] described by Mr. Whitney: Tie two swivels on the line, nine inches apart; a small ring is soldered to one end of the lead, join the two swivels by a piece of weak cotton, thread the cotton through the ring of the lead and shorten it to four inches, which loops up the line, and when the strike comes the lead is released.

In the latter case, which I adopted, I found the simplest way was to cut the line about ten feet from the spoon and fasten the lead by two split rings and two swivels. Starting with a four-ounce lead I soon came to a six ounce, which I believe to be the most suitable, certainly in spring tides.

Odds and Ends.—One must carry out all one's own repairs, therefore an ample supply of repairing material and spare tackle must be taken.

Strong silk for splicing breakages, cobbler's wax, seccotine or liquid glue, rod varnish, spare hooks, split rings, bronze single and double swivels, fine copper wire, snake rod rings, and screws for reels.

A small portable case of tools, such as the "Bonsa," is invaluable, and with this and a sharp clasp knife most current repairs can be made.

Two good spring balances are advisable, one weighing up to seventy or eighty pounds, and one up to fifteen pounds. Both should be tested, which avoids any dispute afterwards as to their accuracy.

The morning of the 27th fulfilled the promise of the previous day. The weather had at last broken, and it was in a dense wetting mist that we crept north, bound for Alert Bay. We had no delay at the Seymour Narrows, which can only be navigated at a certain state of the tide. The whole force of the Pacific runs through these narrows—not more than half-a-mile broad—and the eddies and whirlpools that are formed are terrifying. There is one great rock in the middle of the passage—a special source of danger.

I had visited these narrows in a steam launch from the hotel, and had there seen the water at its worst—a wonderful sight; but the tide was now suitable, and as the Queen City passed through there was only a strong current.

The best guides and hunters are always snapped up early in the season, and before I left England, Mr. Bryan Williams had secured for me the services of Cecil Smith—better known in the local sporting world as "Cougar"[78] Smith, from the number of cougars he had shot. As he lived at Quatiaski Cove, immediately opposite the Willows Hotel, I had frequently met him and discussed our plans together.

We had arranged to go from Alert Bay up the Nimquish River to the Nimquish Lake, from which we were to strike in north-west to some valleys in the interior where wapiti were reported as fairly plentiful. Cecil Smith did not know the ground personally, but his brother Eustace, who had been in that part of the country several times, was to meet us at Alert Bay and act as head guide. Unfortunately for us, at the last moment he was unable to come, and we had to find our way as best we could in an unknown and unmapped country. I had to find a man to replace Eustace Smith, and was fortunate in picking up Joe Thomson at Campbell River, and two better men than Smith and Thomson I could not have had.

Smith was to act as head hunter and guide and Thomson more particularly look after the cooking and camp generally. Thomson came on board with me and we picked up Smith at Quitiaski Cove at about 4 a.m.

Two other members of the party were even of more interest to me than the men. They were "Dick" and "Nigger," the latter generally[79] known as "Satan." "Dick," who belonged to Smith, was a most adorable dog and celebrated throughout Vancouver for treeing cougars; indeed, as Smith himself acknowledged, he owed his reputation as a cougar hunter to Dick, who did everything except the actual shooting. It was difficult to say what Dick's breed was. He looked like a cross between a spaniel and a retriever. He was one of the most fascinating dog characters I have ever met. He adored his master, who returned his worship, but ingratiated himself with every one; soon discovering that I had a warm corner in my heart for all dogs, we at once became fast friends.

"Nigger," the property of Thomson, was a powerful, black, evil-looking bull terrier, but like many of his kind his character belied his looks, for he really was a soft-hearted, affectionate beast with a special ability for making himself comfortable under any circumstances. Thomson asserted that if there was no food, "Nigger" subsisted on berries, and he was an adept at catching fish for himself in the river. He had had some trouble with the authorities at Comox in a matter of sheep, and so a temporary absence from his native town was desirable, and he became, to his great joy, one of our party.

At 2 p.m. on the 27th we arrived at Alert Bay, which is situated on an island opposite where the Nimquish River discharges itself into the sea. Alert Bay is an important settlement of the Siwash Indians, and the village possesses one of the most remarkable collections of Totem Poles on the coast.

The question was, where to put up—hotels there were none. Mr. Chambers, the local merchant, had in the most generous manner built an annexe to his charming house, containing several bedrooms, but they were all occupied. Fortunately, I had been introduced to Mr. Halliday, the Alert Bay Indian Agent, at Campbell River, and he most kindly offered me a shakedown on a sofa in his drawing-room, which I gratefully accepted. I found Mr. Halliday was devoted to music, but seldom could find an accompanist—while to accompany was a pleasure to me, and we passed the evening going through many songs I had not heard for years, which recalled the Old Country and days long gone by.

Eustace Smith met us here and gave a rough sketch map to his brother Cecil, and indeed pointed out to us the peak on Vancouver Island under which we were to camp, and which only looked about fifteen miles off as the crow flies, and yet what difficulty we had afterwards to find our way through the impenetrable forest!

The morning of the 28th was spent in sorting out the kit we could take with us, which, as packing was our only means of transport, had to be cut down to nothing. Mine consisted of two flannel shirts, one change of underclothing, two pairs of socks, one sweater, one spare pair of boots, a few handkerchiefs, sponge, soap and towel. One Hudson Bay blanket, for it was not yet cold in the woods, and one waterproof ground sheet in which the pack was made up, completed my outfit. The men had a single fly to sleep under. My tent, which Mr. Williams had kindly ordered for me in Vancouver, was of the lean-to pattern, made with a flap which let down in front in bad weather, completely closing the tent. Being made of so-called silk, it weighed only five pounds. It measured 7 feet × 6 feet, was about 7 feet high in front and sloped back to about 2 feet high behind. It was most comfortable so long as one slept on the ground, but was not high enough behind to take even a small camp bedstead. It was quite waterproof, but should a spark from the fire fall on it, a hole was burnt rapidly. I understand that the following renders the silk almost fire-proof—

Dissolve half-a-pound of powdered alum in a bucket of soft boiling water. In another bucket half-a-pound sugar of lead; when dissolved and clear, pour first the alum solution, then the sugar of lead, into another vessel; after several hours pour off the water, letting any thick sediment remain, and soak the tent, kneading it well: wring out and hang up to dry.

Camp furniture I had none. A tin plate, knife, fork and spoon for each man; a nest of cooking pots which Thomson provided, a small tin basin in which we washed and which also served to mix our bread, and lastly the invaluable portable tin baker which will roast or bake anything. It was strange that the Hudson Bay Stores at Vancouver could not provide light cooking utensils suitable for packing. They had excellent blankets, waterproof sheets and the larger articles of camp equipment, but light cooking utensils there were none. Mr. Williams took infinite trouble to get a nest of cooking pots made for me, but on their arrival at Campbell River they were found impossible owing to their weight, so I made them a present to Smith.

We fitted out as regards provisions at Mr. Chambers' Store: the usual articles of food—bacon, pork, beans, tea, sugar, flour, baking[83] powder, oatmeal, dried apples and peaches, a couple of tins of meat, a couple of tins of jam—one of which only sufficed for a meal—some butter as a great treat, and a few potatoes and onions on which I insisted.