| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924027829666 |

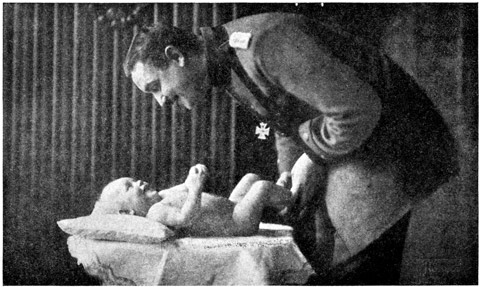

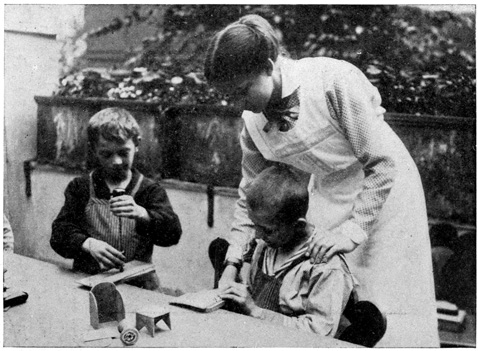

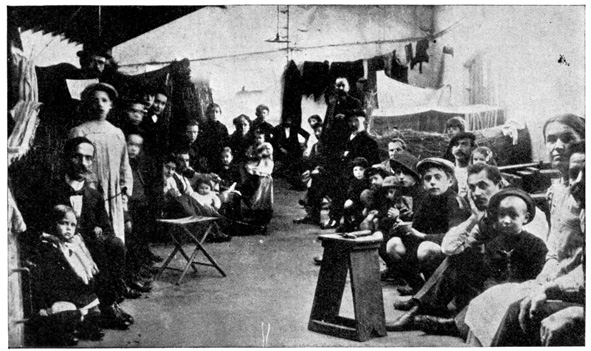

Germany's Youngest Reserve.

WHAT AN AMERICAN GIRL

SAW AND HEARD

BY

MARY ETHEL McAULEY

CHICAGO

THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY

1917

COPYRIGHT BY

THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY

1917

DEDICATION

TO MY MOTHER

WHO SHARED THE TRIALS OF

TWO YEARS IN GERMANY

WITH ME

This book is the product of two years spent in Germany during the great war. It portrays what has been seen and heard by an American girl whose primary interest was in art. She has tried to write without fear or favor the simple truth as it appeared to her.

| PAGE | |

| Getting into Germany in War Time | 1 |

| Soldiers of Berlin | 7 |

| The Women Workers of Berlin | 20 |

| German "Sparsamkeit" | 35 |

| The Food in Germany | 49 |

| What We Ate in Germany | 62 |

| How Berlin is Amusing Itself in War Time | 69 |

| The Clothes Ticket | 81 |

| My Typewriter | 88 |

| Moving in Berlin | 93 |

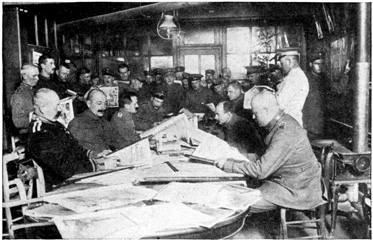

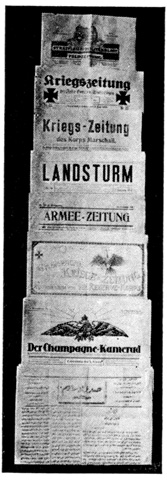

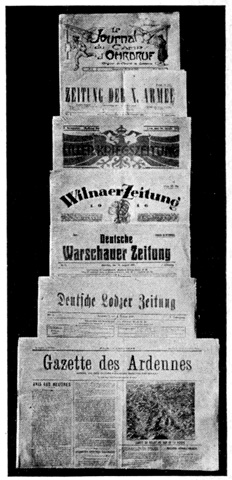

| What the Germans Read in War Time | 98 |

| Precautions Against Spies, etc. | 108 |

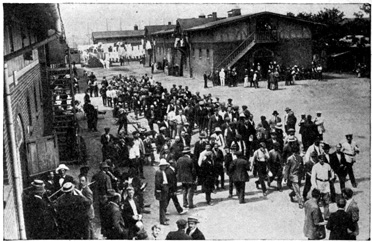

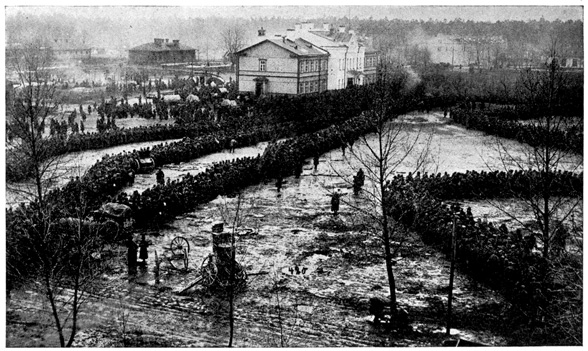

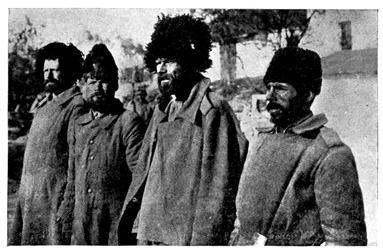

| Prisoners in Germany | 115 |

| Verboten | 128 |

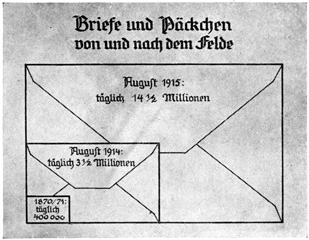

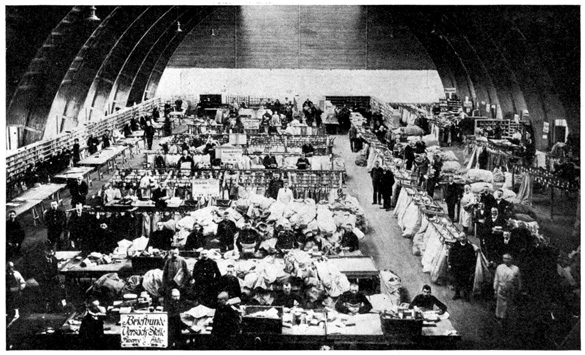

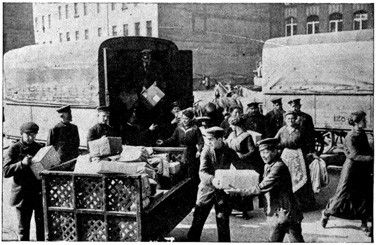

| The Mail in Germany | 132 |

| The "Ausländerei" | 140 |

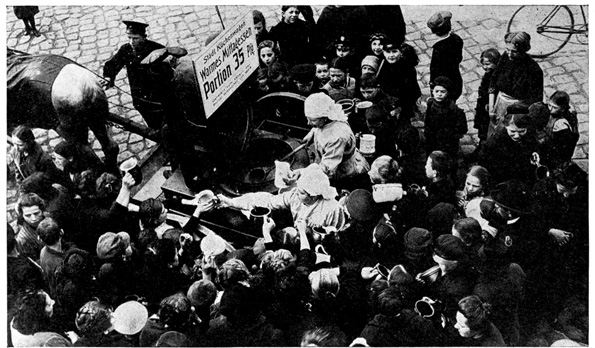

| War Charities | 146 |

| What Germany is Doing for Her Human War Wrecks | 159 |

| Will the Women of Germany Serve a Year in the Army? | 173 |

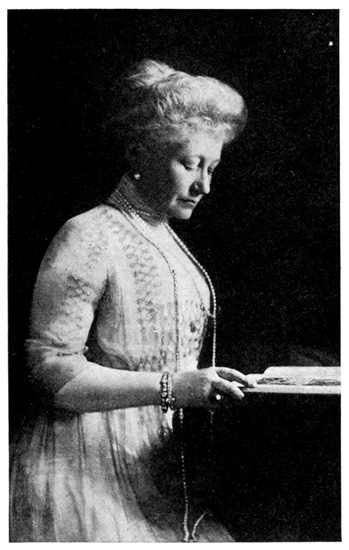

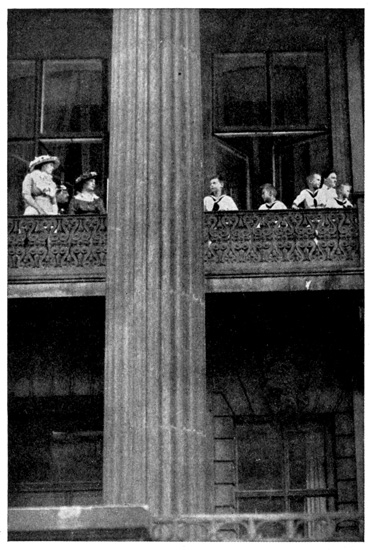

| The Kaiserin and the Hohenzollern Princesses | 184 |

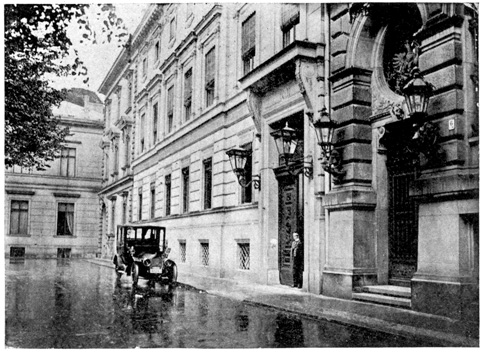

| A Stroll Through Berlin | 196 |

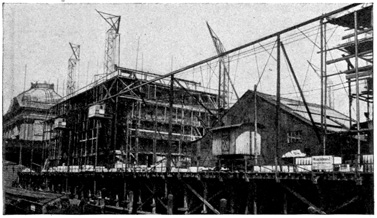

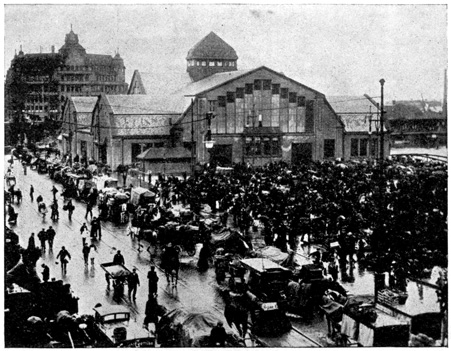

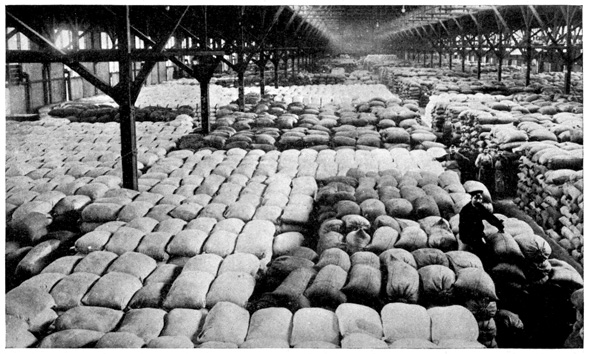

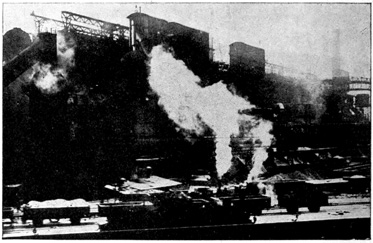

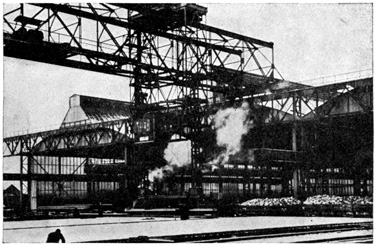

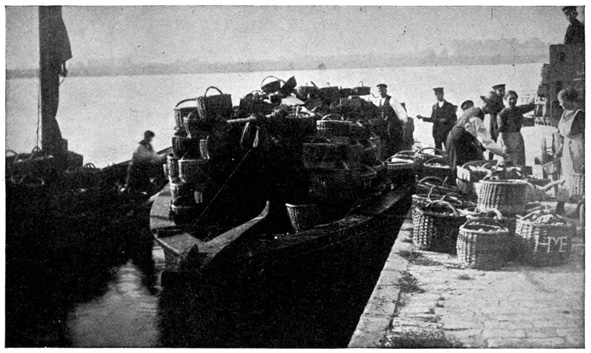

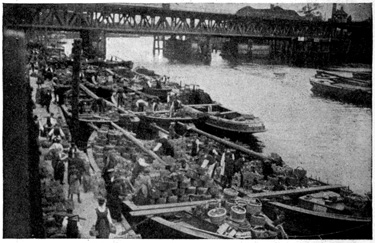

| A Trip Down the Harbor of Hamburg | 207 |

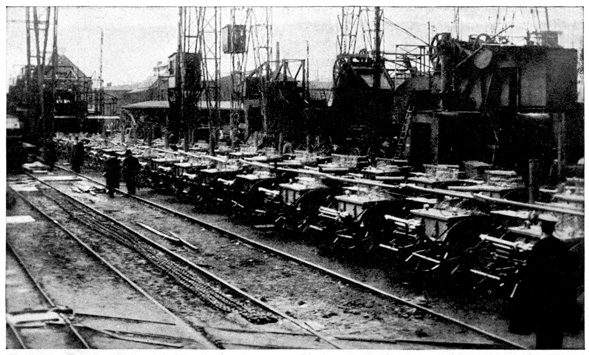

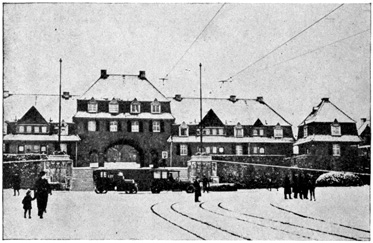

| The Krupp Works at Essen | 218 |

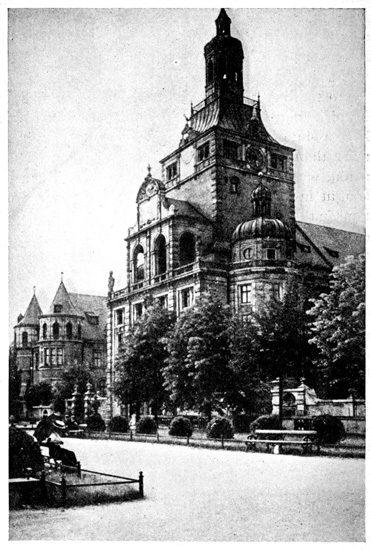

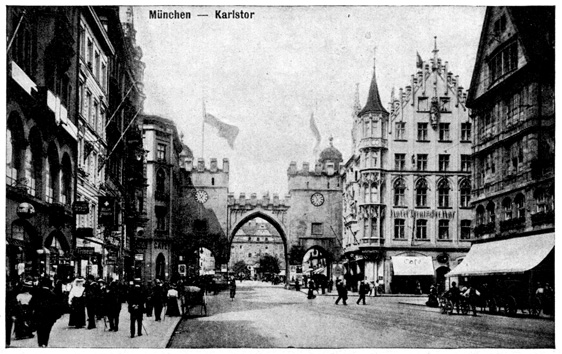

| Munich in War Time | 228 |

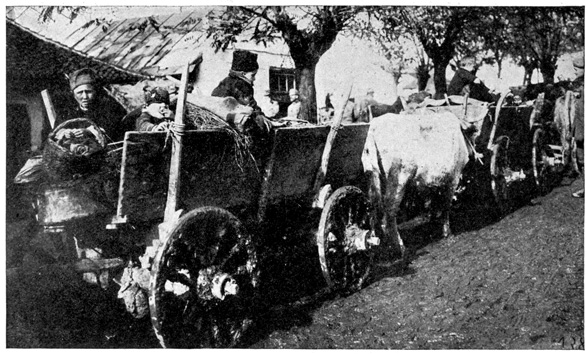

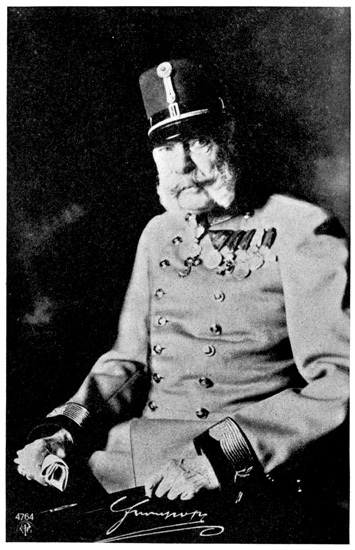

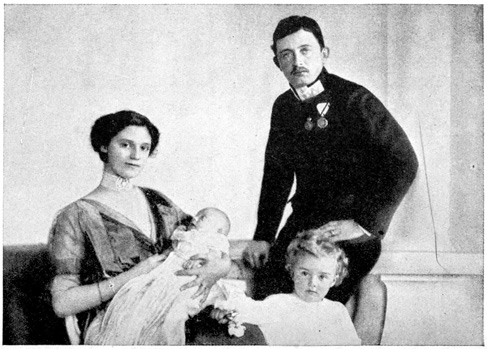

| From Berlin to Vienna in War Time | 242 |

| Vienna in War Time | 256 |

| Soldiers of Vienna | 267 |

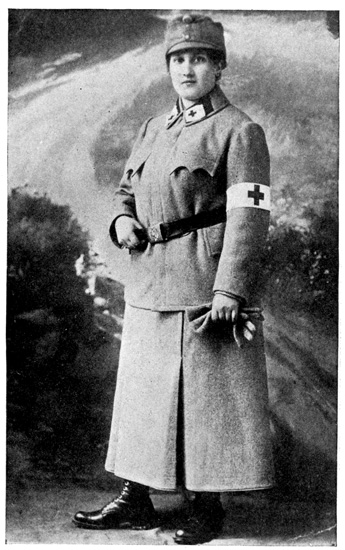

| Women Warriors | 279 |

| How Americans Were Treated in Germany | 286 |

| I Leave Germany July 1, 1917 | 292 |

Now that America and Germany are at war, it is not possible for an American to enter the German Empire. Americans can leave the country if they wish, but once they are out they cannot go back in again.

Since the first year of the war there has been only one way of getting into Germany through Denmark, and that is by way of Warnemünde. After leaving Copenhagen you ride a long way on the train, and then the train boards a ferry which takes you to a little island. At the end of this island is the Danish frontier, where you are thoroughly searched to see how much food you are trying to take into Germany. After this frontier is passed you ride for a few hours on a boat which carries you right up to Warnemünde, the German landing-place and the military customs of Germany.

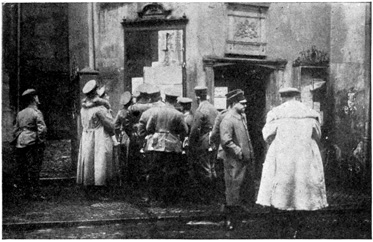

When I went to Germany in October, 1915, the regulations were not very strict, travelers had only to show that they had a good reason for going into the country, and they were searched—that was all. But during the two years I was in Germany 2 all this was changed. Now it is very hard for even a neutral to enter Germany. Neutrals must first have a visé from the German consul in Denmark. It takes four days to get this visé, and you must have your picture taken in six different poses. Also, you must have a legitimate reason for wanting to go into the country, and if there is anything the least suspicious about you, you are not granted a permit to enter.

Travelers entering Germany bring as much food with them as they can. You are allowed to bring a moderate amount of tea, coffee, soap, canned milk, etc.; nine pounds of butter and as much smoked meat as you can carry. No fresh meat is allowed, and you must carry the meat yourself as no porters are allowed around the docks. This is a spy precaution.

The butter and meat are bought in Copenhagen from a licensed firm where it is sealed and the firm sends the package to the boat for you. You must be careful not to break the seal before the German customs are passed. The Danes are very strict about letting rubber goods out of their country, and one little German girl I knew was so afraid that the Danes would take her rubbers away from her, that she wore them on a hot summer day.

The boat which takes passengers to and from Warnemünde is one day a German boat and the next day a Danish boat. If you are lucky and make the trip on the day the Danish boat is running, you 3 get a wonderful meal, and if you are unlucky and strike the German day, you get a poor one. After getting off the boat, you get your first glimpse of the German Militär, the soldiers at the customs.

The travelers are divided into two classes—those going to Hamburg and those going to Berlin. Then a soldier gets up on a box and asks if there is any one in the crowd who has no passport. The day I came through only one man stepped forward. I felt sorry for him, but he did not look the least bit disheartened. An officer led him away. Strange to say, four days later we were seated in a hotel in Berlin eating our breakfast when this same little man came up and asked if we were not from Pittsburg, and if we had not come over on the "Kristianiafjord." When I said that we had, he remarked: "Well, I am from Pittsburg, too, and I came over on the 'Kristianiafjord.'"

"But I did not see you among the passengers," I said.

"No," he answered, "I should say not. I was a bag of potatoes in the hold. I am a reserve officer in the German army, and I was determined to get back to fight. I came without a passport claiming to be a Russian. It took me three days to get fixed up at Warnemünde because I had no papers of any kind. The day I had everything straightened out and was leaving for Berlin, a funny thing happened. I was walking along the street with an officer when a crowd of Russian prisoners came along. To my 4 surprise one of the fellows yelled at me, 'Hello, Mister, you'se here too?' And I knew that fellow. He had worked for my father in America. As he was returning to Russia, he was taken prisoner by the Germans. I had an awful time explaining my acquaintance to the authorities at Warnemünde, but here I am waiting to join my regiment."

At Warnemünde, after the people are divided into groups, they are taken into a large room where the baggage is examined. At the time I came through we were allowed to bring manuscript with us, but it had to be read. Now not one scrap of either written or printed matter can be carried, not even so much as an address. All the writing now going into Germany must be sent by post and censored as a letter.

When I came through I had a stack of notes with me and I never dreamed that it would be examined. I was having a difficult time with the soldier who was searching me when an officer who spoke perfect English came up and asked if he could help me. He had to read all my letters and papers, but he was such a slow reader that the train was held up half an hour waiting for him to finish reading them. Nothing was taken away from me, but they took a copy of the London Illustrated News away from a German who protested loudly, waving his hands. It was a funny thing to do, for in Berlin this paper was for sale on all the news stands and in the cafés. But sometimes the Germans make it a point of 5 treating foreigners better than they do their own people. I noticed this many times afterward.

After the baggage was examined, the people had to be searched. The men didn't have to undress and the women were taken into a small room where women searchers made us take off all our clothes. They even make you take off your shoes, they feel in your hair and they look into your locket. As I had held up the train so long, I did not have much time to dress and hurried into the train with my hat in my hand and my shoes untied. As the train pulls out the searcher soldiers line up and salute it. Searching isn't a very nice job, and when my mother went back to America the next spring, no less than four of the searchers told her that they hated it and that when the war was over the whole Warnemünde force was coming to America.

The train was due in Berlin at 9 o'clock at night, but we were late when we pulled in at the Stettin Station. We had a hard time getting a cab and finally we had to share an automobile with a strange man who was going to the same hotel. At 10 o'clock we were in our hotel on Unter den Linden. From the window I could look out on the linden trees. The lights were twinkling merrily in the cafés across the way. Policemen were holding up the traffic on the narrow Friedrichstrasse. People were everywhere. It did not seem like a country that was taking part in the great war. 7

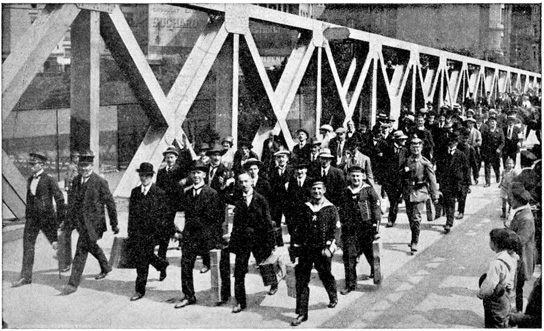

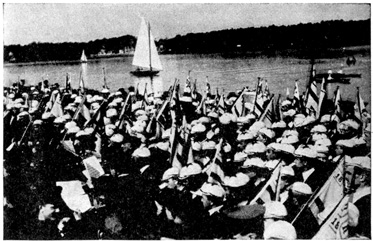

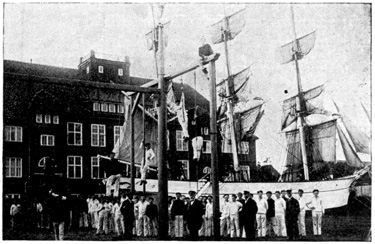

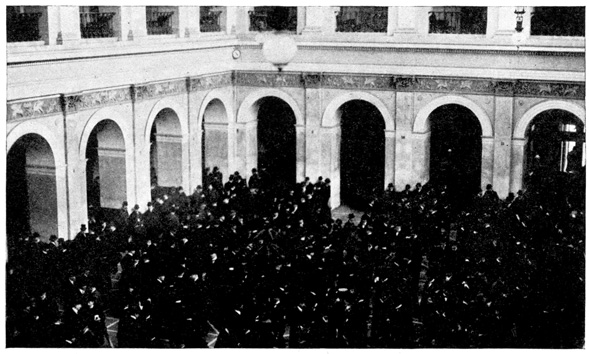

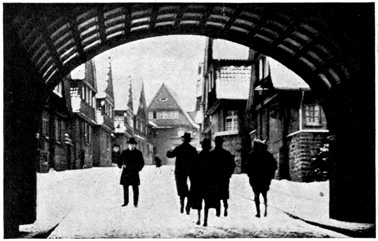

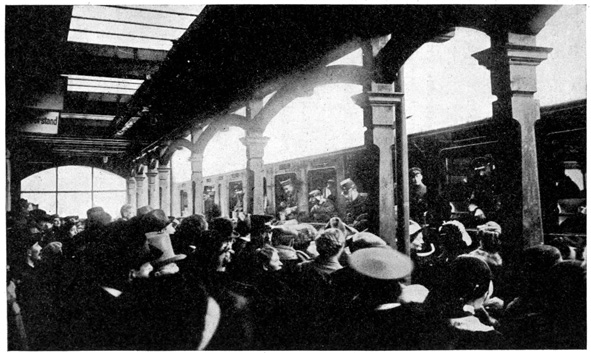

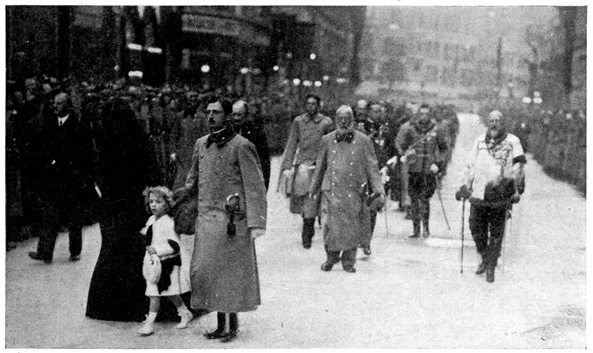

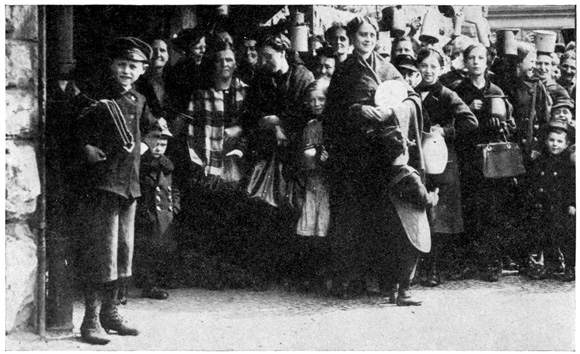

Marine Reserves on Their Way to the Station. Wilhelmshaven.

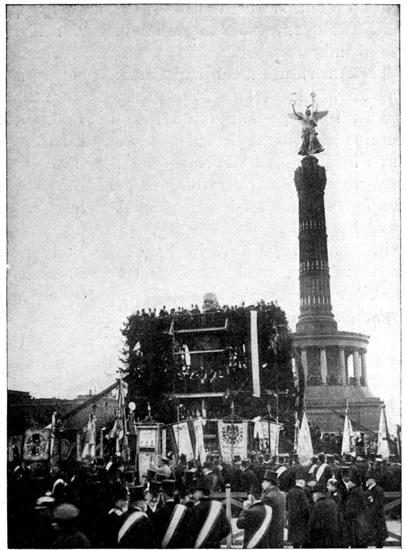

Berlin is a city of soldiers. Every day is soldiers' day. And on Sundays there are even more soldiers than on week days. Then Unter den Linden, Friedrichstrasse and the Tiergarten are one seething mass of gray coats—gray the color of everything and yet the color of nothing. This field gray blends with the streets, the houses, and the walls, and the dark clothes of the civilians stand out conspicuously against this gray mass.

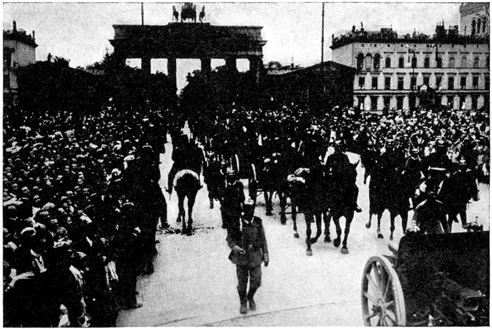

Soldiers Marching Through Brandenburg Gate.

When I first came to Berlin, I thought it was just by chance that so many soldiers were there, but the army seems ever to increase—officers, privates, sailors and men right from the trenches. During the two years that I was in Berlin this army remained the same. It didn't decrease in numbers and it didn't change in looks. The day I left Berlin it looked exactly the same as the day I entered the country. They were anything but a happy-looking bunch of men, and all they talked about was, "when the war is over"; and like every German I met in those two years, they longed and prayed for peace. One day on the street car I heard a common 8 German soldier say, "What difference does it make to us common people whether Germany wins the war or not, in these three years we folks have lost everything." But every German soldier is willing to do his duty.

The most wonderful thing about this transit army is that everything the soldiers have, from their caps to their shoes, is new, except the soldiers just coming from the front. And yet as a rule they are not new recruits starting out, but men who have been home on a furlough or men who have been wounded and are now ready to start back to the front. To believe that Germany has exhausted her supply of men is a mistake. Personally, I know lots of young Germans that have never been drafted. The most of these men are such who, for some reason or other, have had no army service, and the German military believe that one trained man is worth six untrained men, and it is the trained soldier that is always kept in the field. If he has been wounded he is quickly hurried back to the front. By their scientific methods a bullet wound can be entirely cured in six weeks.

The Most Popular Post-Card in Germany.

German men have never been noted dressers, and even at their best the middle and lower classes look very gawky and countrified in civilian clothes. You cannot imagine how the uniform improves their appearance. I have seen new recruits marching to the place where they get their uniforms. Most of them have on old ill-fitting clothes, slouch hats and 10 polished boots. They shuffle along, carrying boxes and bundles. They have queer embarrassed looks on their faces. Three hours later, this same lot of men come forth. They are not the same men. They have a different fire in their eyes, they hold themselves straighter, they no longer slouch but keep step. The uniform seems to have made new men of them. It should be called "transform," not uniform.

At the Friedrichstrasse Station one can see every kind of soldiers at once. There the men arrive from the front sometimes covered with dust and mud, and once I saw a man with his trousers all spattered with blood. The common soldiers carry everything with them. On their backs they have their knapsacks, and around their waists they have cans, spoons, bundles and all sorts of things. These men carry sixty-five pounds with them all the time. In one of their bags they carry what is known as their eiserne Portion or their "iron portion." This consists of two cans of meat, two cans of vegetables, three packages of hard tack, ground coffee for several meals and a flask of whisky. The soldiers are not allowed to eat this portion unless they are in a place where no food can be brought to them, and then they are only allowed to eat it at the command of a superior officer. In the field the iron portions are inspected each day, and any soldier that has touched his portion is severely punished.

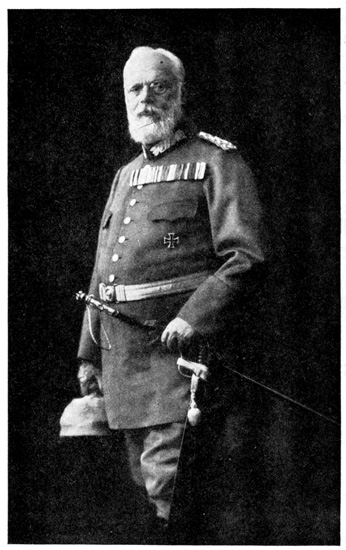

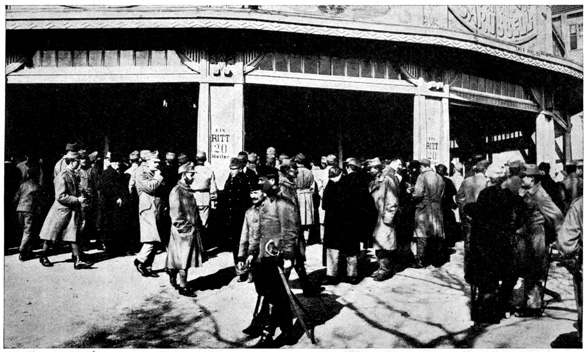

Schoolboys' Reserve. Berlin.

A great many of the soldiers have the Iron Cross 12 of the second class, but very rarely a cross of the first class is seen. The second class cross is not worn but is designated by a black and white ribbon drawn through the buttonhole. The first class cross is worn pinned rather low on the coat. The order Pour le mérite is the highest honor in the German army, and not a hundred of them have been given out since the beginning of the war. It is a blue, white and gold cross and is hung from the wearer's collar. A large sum of money goes with this decoration. The second class Iron Cross makes the owner exempt from certain taxes; and five marks each month goes with the first class Iron Cross.

The drilling-grounds for soldiers are very interesting. Most of these places are inclosed, but the one at the Grunewald was open, and I often used to go there to see the soldiers. It made a wonderful picture—the straight rows of drilling men with the tall forest for a background. The men were usually divided off into groups, a corporal taking twelve men to train. It was fun watching the new recruits learning the goose-step. The poor fellows tried so hard they looked as though they would explode, but if they did not do it exactly right, they were sent back to do it over again. The trainers were not the least bit sympathetic.

One day an American boy and I went to Potsdam. We were standing in front of the old Town Palace watching some fresh country boys drill. I laughed outright at one poor chap who was trying to goose-step. 14 He was so serious and so funny I couldn't help it. The corporal came over to us and ordered us to leave the grounds, which we meekly did.

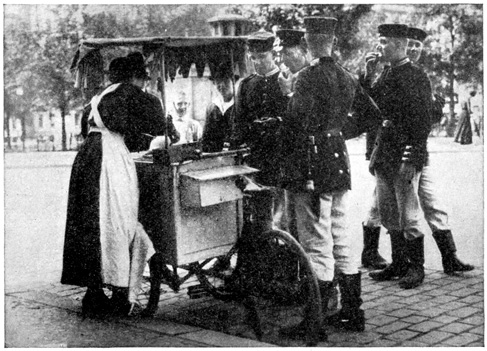

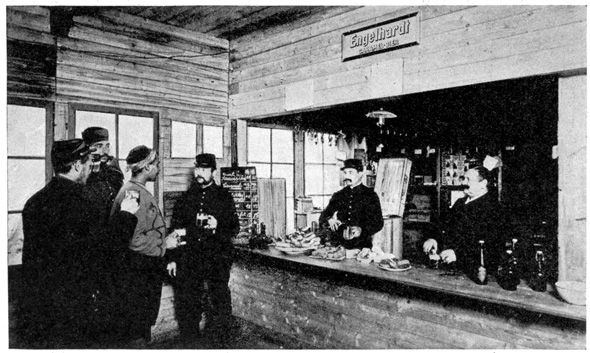

Soldiers Buying Ices in Berlin. A War Innovation.

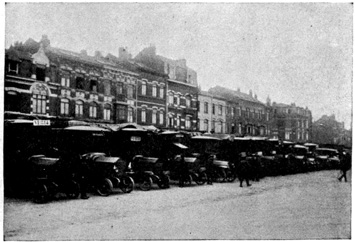

Tempelhof, the largest drilling-ground in Berlin, is the headquarters for the army supplies, and here 15 one can see hundreds of wagons and autos painted field-gray. The flying-place at Johannisthal is now enclosed by a fence and is so well guarded you can't get within a square of it.

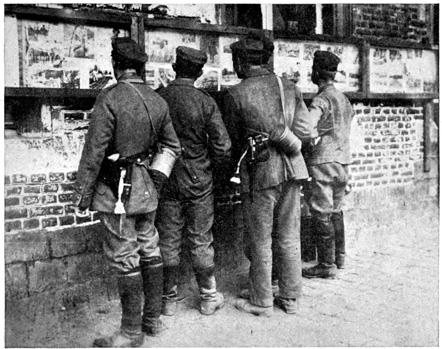

Looking at Colored Pictures in an Old Book-Shop.

It is very interesting to watch the troop trains coming in from the front. When I first went to Berlin it was all a novelty to me and I spent a great 16 deal of my time at the stations. One night just before Christmas, 1915, the first Christmas I was in Berlin, I spent three hours at the Anhalt Station watching the troops come home. They were very lucky, these fellows, six months in the trenches 17 and then to be home at Christmas time! They were the happiest people I had seen in the war unless it were the people who came to meet them.

Cheering the Soldier on His Way to the Front.

Most of the soldiers were sights. Their clothes were dirty, torn and wrinkled. Many of them coming from Russia were literally covered with a white dust. At first I thought that they were bakers, but when I saw several hundred of them I changed my mind. Beside his regular paraphernalia, each soldier had a dozen or more packages. The packages were strapped on everywhere, and one little fellow had a bundle stuck on the point of his helmet.

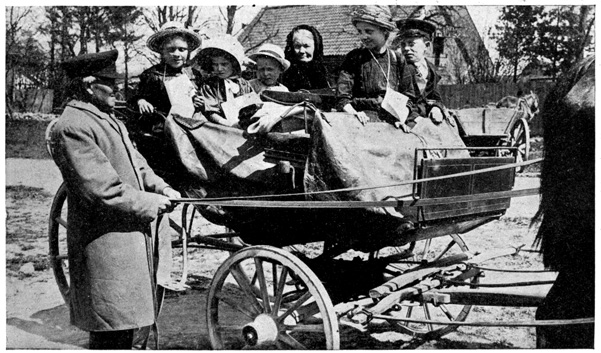

A little child, perhaps three years old, was being held over the gate near me and all the while he kept yelling, "Papa! Urlaub!" An Urlaub is a furlough, and when the father did come at last the child screamed with delight. Another soldier was met by his wife and a tiny little baby. He took the little one in his arms, and the tears rolled down his cheeks, "My baby that I have never seen," he said.

This night the soldiers came in crowds. Everybody was smiling, and in between the trains we went into the station restaurant. At every table sat a soldier and his friends. One young officer had been met by his parents, and he was so taken up with his mother that he could not sit down but he hung over her chair. Was she happy? Well, I should say so!

At another table sat a soldier and his sweetheart. They did not care who saw them, and can you blame them? He patted her cheeks and he kissed her hand.... 18 An old man who sat at the table pretended that he was reading, and he tried to look the other way, but at last he could hold himself no longer, and grasping the soldier's hand he cried, "Mahlzeit!"

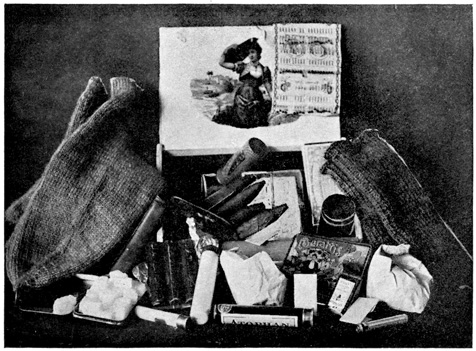

A Field Package for a German Soldier.

We went out and saw more trains and more soldiers. 19 A little old lady stood beside us. She was a pale little lady dressed in black. She was so eager. She strained her eyes and watched every face in the crowd. It was bitter cold and she was thinly clad. At 12 o'clock the station master announced that there would be no more trains until morning. The little old lady turned away. I watched her bent figure as she went down the stairs. She was pulling out her handkerchief. 20

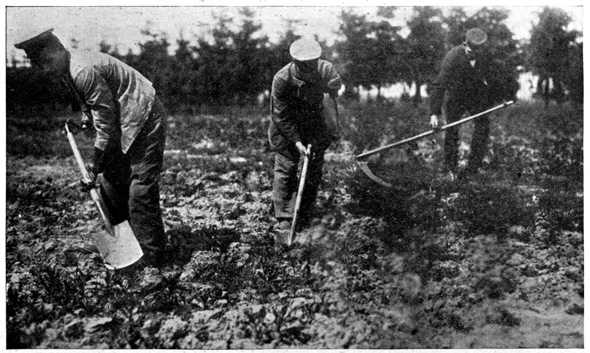

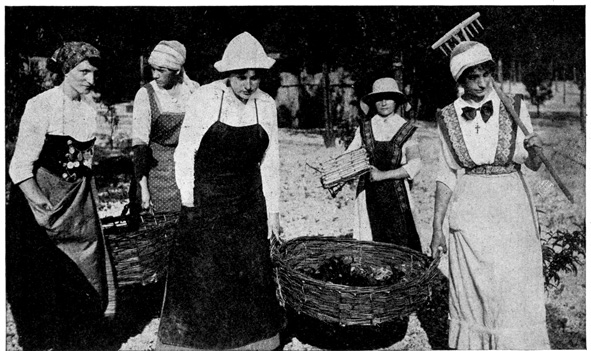

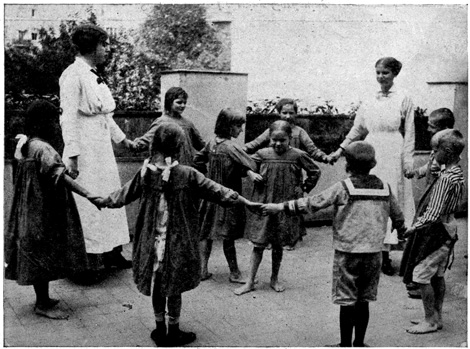

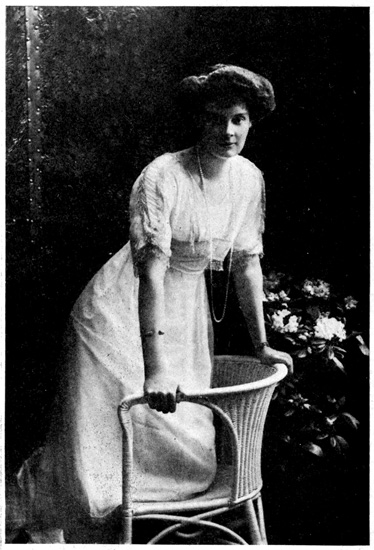

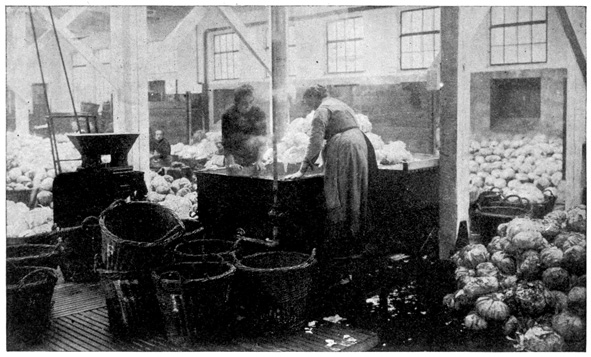

The German women have filled in the ranks made vacant by the men. Nothing is too difficult for them to undertake and nothing is too hard for them to do.

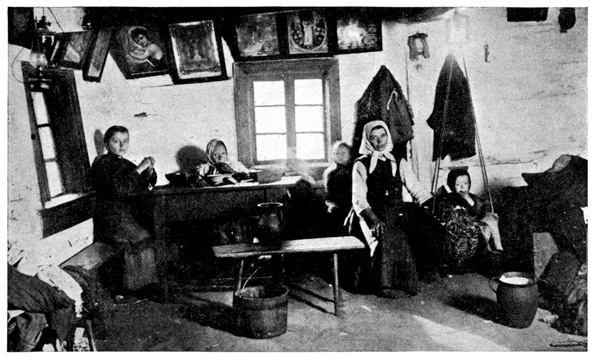

The poor German working women! No one in all the war has suffered like these poor creatures. Their men have been taken from them, they are paid only a few pfennigs a day by the government, and now they must work, work like a man, work like a horse.

The German working woman is tremendously capable in manual labor. She never seems to get tired and she can stand all day in the wet and snow. But as a wife and mother she is becoming spoiled. She is bound to become rough, and she takes the jostlings of the men she meets with good grace, answering their flip remarks, joking with them and giving them a physical blow when she thinks it necessary. Most of the women seem to like this familiarity which working on the streets brings them, and they find it much more exciting than doing housework at home. 21

All great reforms begin in a violent way, and maybe this is the beginning of emancipation for the German woman, for she is beginning to realize what she can do, and for the first time in the history of the empire she is living an independent existence, dependent upon no man.

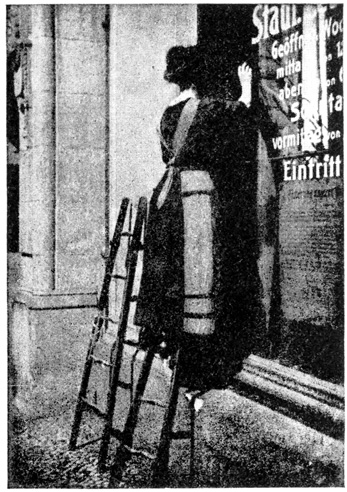

A Window Cleaner.

When the war first broke out, women were taken on as ticket punchers on the overground and underground railways, and Frau Kneiperin, or "Mrs. Ticket-puncher," sits all day long out in the open, punching tickets. In summer this job is very pleasant, 22 but in winter she gets very, very cold even if she does wear a thick heavy overcoat and thick wooden shoes over her other shoes. She can't wear gloves for she must take each ticket in her hand in order to punch the stiff boards. She earns three marks a day.

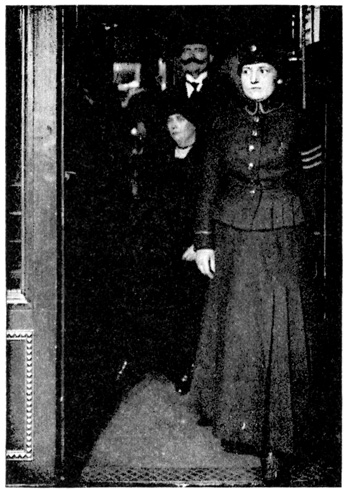

A German Elevator "Boy."

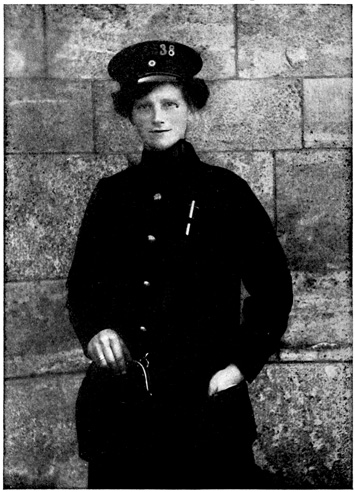

After the women ticket punchers came the women door shutters, and Frau Türschliesserin, or "Mrs. Door Shutter," is all day long on the platforms of the stations, and she must see that every train door is shut before the train starts. This is a lively job, 23 and she must jump from one door to the other. Most of these women wear bloomers, but some of them wear men's trousers tucked in their high boots. They all wear caps and badges.

Frau Briefträgerin is the woman letter carrier. This is rather a nice job, carrying only a little bag of letters. One fault with the work is that she must deliver the letters to the top floor of every building whether there is an elevator or not, but as no German building is more than five stories high, it is not so bad. Most of the special delivery "boys" are women. They wear a boy's suit and ride a bicycle.

More than half the street car conductors in Germany now are women. Most of these women still cling to skirts, but they all wear a man's cap and coat. They are quite expert at climbing on the back of the car and fixing the trolley, and if necessary they can climb on the top of the car. If the car gets stuck, they get out and push it, but the crowd is generally ready to help them. They have their bag for tips, and they expect their five pfennigs extra the same as a man.

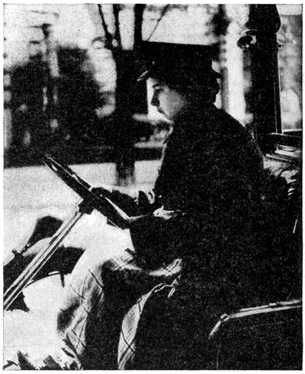

When Frau Führerin, or "Mrs. Motorman," came, some of the German people were scandalized and exclaimed: "Well, I will never ride on a street car run by a woman. It wouldn't be safe." Now, no one thinks anything about it, and the women have no more accidents than the men. Some of these women are little bits of things, and one 24 wonders that they have the strength to stand it all day long. Most of them look as if it were nerve-racking. They earn three and a half marks a day.

Costume of a Street-Car Conductor.

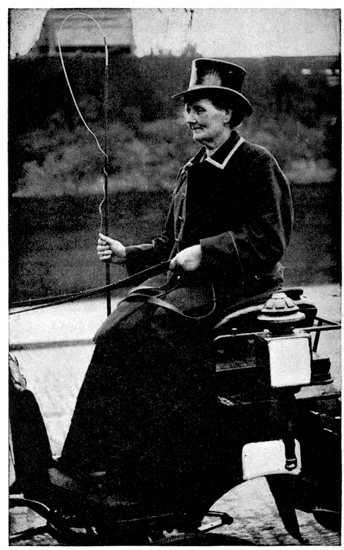

Women cab drivers are not very numerous, but every now and then one of them whizzes around a corner looking for a fare. One Berlin cabby is quite an old lady. The men cabbies are jealous of the women because the women get the best tips. There are few women taxi drivers. One young woman driver has a whole leather suit with tight breeches and an aviator hat. Women also drive mail wagons, and women go around from one store to another cleaning windows. Frau Fensterputzerin or "Mrs. Window Cleaner" carries a heavy ladder with her. This is no light task.

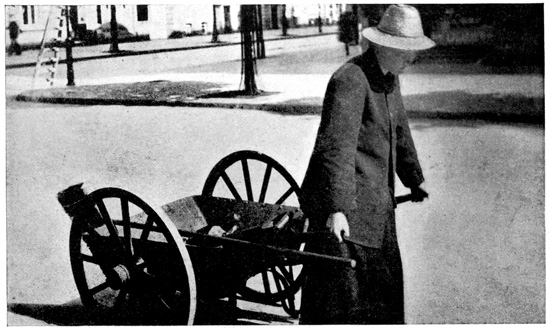

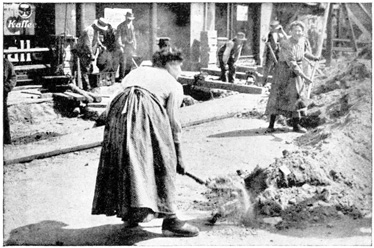

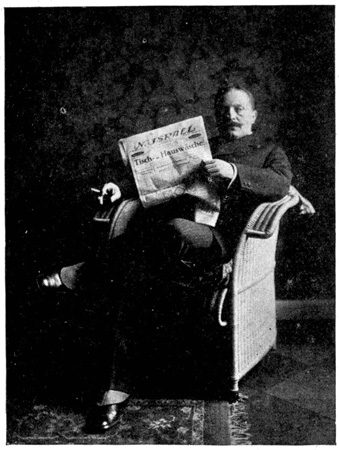

They have always had women street cleaners and switch tenders in Munich, but now they have them in Berlin as well. They work in groups, sweeping the dirt and hauling it away in wheelbarrows. Just before I left Berlin I saw a woman posting bills on the round advertising posts. She did not seem to be an expert at managing the paste, because she flung it around so that it was dangerous to come near her. In the last year they have had women track walkers, and they pace the railroad ties to see if the tracks are safe. They dress in blue and carry small iron canes.

A Famous "Cabby" in Berlin.

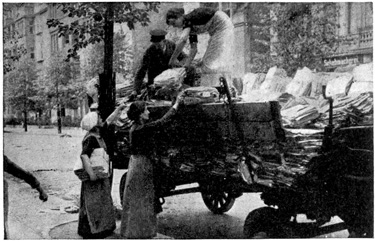

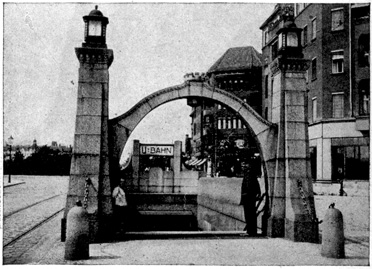

The excavation for the new underground railway under Friedrichstrasse was dug out by women, and half the gangs that work on the railroad tracks are women. They fasten bolts and saw the iron rails. 26 All the stores have women elevator runners, and most of the large department stores have women checking umbrellas, packages, dogs, and—lighted cigars! Most stores have women floor-walkers. Most of the delivery wagons are run by women, and they carry the heaviest packages.

All the newspapers in Berlin are sold by women, and they wheel the papers around in baby carriages. Around the different freight stations one can see women loading hay and straw into the cars. They wield the pitchfork with as much ease as a man and with far more grace. Many of the "brakemen" on the trains are women, and some of the train conductors are women. Most of the gas-meter readers are women, and other women help to repair telephone wires, and still others help to instal telephones.

There are a few Frau Schornsteinfegerin, or "Mrs. Chimney Sweep," but the job of being a chimneysweep doesn't appeal to most women. These women wear trousers and a tight-fitting cap. They mount the house tops and they make the soot fly, and the cement rattles down the chimney. They carry long ropes with which they pull their brushes up and down.

Cleaning the Streets in Berlin.

Frau Klempnermeisterin, or "Mrs. Master Tinner," repairs the roofs. Of course she wears trousers to make climbing easier. Most of the women who have these odd jobs are those whose husbands had the same before the war. Many other women 28 work in the parks cutting the grass and watering the flowers. In the market places women put rubber heels on your shoes while you wait.

Most of the milk wagons are run by girls, and women help to deliver coal. They have no coal chutes in Germany, and the coal is carried from the wagon into the house. This is really terrible work for a woman. A few women work on ash wagons, others are "ice men," and others build houses.

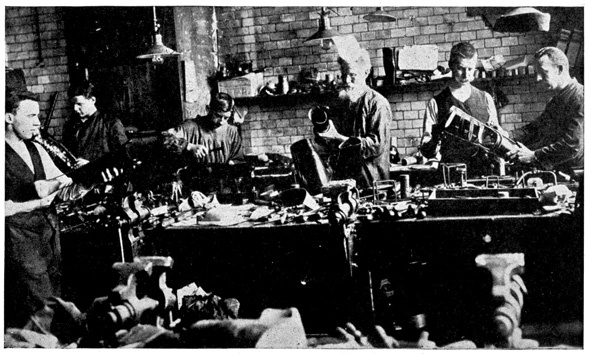

Nearly all the munition workers in Germany are women, and they are paid very high for this work. Most of them get from $40 to $50 a month, wages before unknown for working women. The strength of some of these women is almost beyond belief. Dr. Gertrude Baumer, the famous German woman writer and settlement worker, told me that shells made in one factory weighed eighty pounds each and that every day the women working lifted thirty-six of these shells. Women are also employed in polishing the shells.

The women workers in munition factories are very closely watched, and if the work does not agree with them they are taken away and are given other employment. The sanitary conditions of these factories are very good, and they are almost fire-proof, and they have no horrible fire disasters. Indeed they have very few fires in Germany.

They have in Berlin what is known as the Nationaler Frauendienst, or the "National Women's Service," and it is an organization to help the poor 30 women of Germany during the war. Dr. Gertrude Baumer is the president of this organization, and she is also one of the strongest advocates for the one year army service for German women.

A Berlin Street-Car Conductor.

This society finds employment for women and gives out work for women who have little children and cannot leave home. Women who sew at home make bags for sand defenses, and they make helmet covers of gray cloth. These covers keep the enemy from seeing the shining metal of the helmet. If a woman is sick and cannot work the society takes care of her until she is better and able to work again. They also have food tickets which they give to the poor.

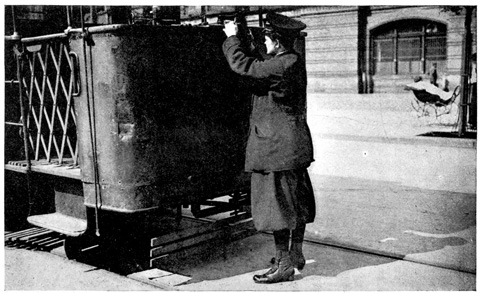

Reading the Gas Meter.

A Chauffeur.

Pension schedules are being made up by different 32 societies, and it is not yet certain which one the government will adopt; at present every woman whose husband is in the war is given a certain amount for herself and children. For women who are now widows the pension is according to the rank of the husband. For instance, the widow of a common soldier gets 300 marks a year. If she has one child she get 568 marks and so on, increasing according to the number of children, for four children she gets 1072 marks. The widow of a non-commissioned officer, a corporal or a sergeant, gets a 33 little more, and the widow of a lieutenant gets over twice as much as a common soldier's widow. The widow of a major-general gets 3246 marks a year. When she has children, she gets very little more, for when a man has risen to the rank of major-general the chances are that he is old and that his children are grown up and able to take care of themselves.

Digging the Tunnel for the New Underground Railway in Berlin.

These schedules are also controlled by the number of years a man has served in the army, and they are trying to pass a new bill which requires that pensions shall be controlled by the salary the man had before the war. If the dead man had worked himself up into a good position of 1000 marks a month, his family should have more than the family of a man who could only make 300 marks a month. 34

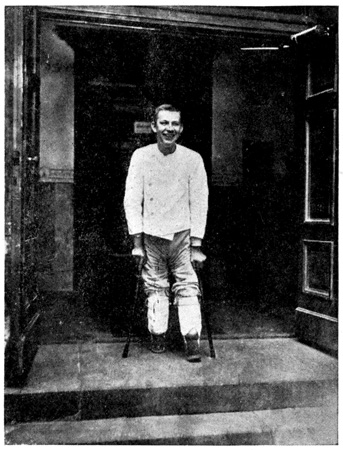

The schedule as it now stands for wounded men is that a private who has lost his leg gets 1,368 marks a year; a lieutenant gets 4851 marks a year; and a general 10,332 marks a year.

Caring for the Trees.

They have in Germany a "votes for women" organization of 600,000 members, but it will be years and years before it ever comes to anything, for German women are very slow in acting and thinking for themselves. 35

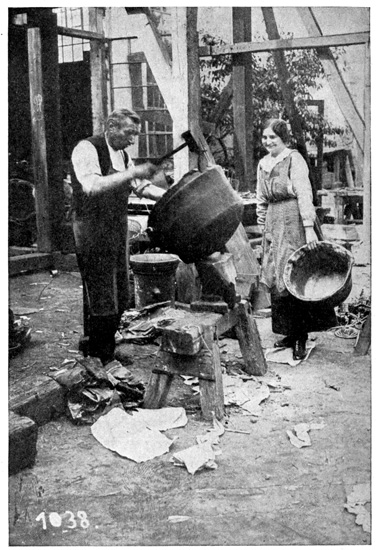

When the blockade of Germany began, no one believed that she could hold out without supplies from the outside world; that in a short time her people would be starving and that she would be out of raw material. During the few months before the blockade was declared, Germany had shipped into her ports as much cotton, copper, rubber and food as was possible. After the blockade started much stuff was obtained from Holland and Scandinavia. From the very first days of the war Germany set to work to utilize all the material that she had on hand, and her watchword to her people was "waste nothing."

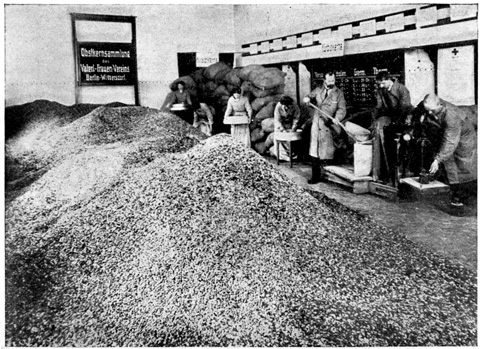

Collecting Cherry Stones for Making Oil.

The first collection of material in Germany was a metal collection, and it took place in the fall of 1915, just after I came to Berlin. This collection extended all over Germany and took place in different parts at different times. Every family received a printed notice of the things that must be given up to the State. It was a long list, but the main thing on it was the brass ovendoors. As nearly every room in Germany has a stove with two of these 36 doors about a foot wide and three quarters of a foot high you can get some idea of how much material this collection brought. Since this collection the doors have been replaced by iron ones that are not nearly so pretty. All kinds of brass pots and kettles were collected, but with special permits people were allowed 37 to keep their heirlooms. Everything was paid for by the weight, artistic value counted for naught. Vacant stores were rented for storing this collection and the people had to bring the things there.

In some cities the people willingly gave up the copper roofs of their public buildings. Copper roofs have always been very popular in Germany. In Berlin the roof of the palace, the cathedral and the Reichstag building are of copper, and in Dresden the roofs of all the royal buildings are of copper.

A friend of mine who is a Catholic went to church one Sunday just before I left Berlin. Before the service opened and just as the priest mounted the pulpit the church bells began to ring. When they had stopped the priest announced that this was the last time the bells would ever ring, for they were to be given to the metal collection. The people began to cry as the priest went on, and before he had finished, many were sobbing out loud. Even the men wept. My friend said that it was the most impressive thing that she had ever witnessed.

In that first copper collection they got enough metal to last several years, but if a second collection is necessary they can take the brass door knobs which are very large and heavy. All the door knobs in Germany are made of brass and this would make a vast amount of metal.

Women Collecting Old Papers.

In April, 1917, they took an inventory of all the aluminum in the empire. People had to send in lists of what they had. The ware was not collected 38 but it was to be given up at any time the government wanted it. The aluminum is to be used in making money. For a long time they have had iron 5- and 10-pfennig pieces, and now they have 1-pfennig pieces made out of aluminum. In Leipsic and Dresden they have 50-pfennig pieces made out of paper, and Berlin will soon have them too. Before the iron money was made in the winter of 1915, small change was very scarce. The store-keepers would rather you would not buy than give you all their small change. At that time in Turkey also small change was so scarce that the people stood in line by the hour to get it. The reason for the scarcity in Germany is that the German soldiers have carried it away to the conquered lands where German money is used as well as native money. In 39 Germany we used, and they still use, postage stamps for small change, but this is very unsatisfactory as they get very dirty in the handling.

Women Collecting Old Papers.

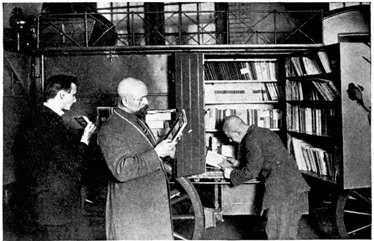

The collection of old paper never ceases in Germany. All over Berlin they have places where this paper is accumulated and sold, and women work all day bringing it in. Every kind of old paper is bought, books, magazines and newspapers. Everything must be brought in flat, and a good price is paid for it.

Another collection that is always going on is the fruit stone collection. They collect cherry stones, peach stones, plum stones, and apple and pear seeds. These collections take place in the public schools and all over Berlin you see pretty posters, "Send the stones to the schoolhouse with your children." The seeds are used for making fat and oil. 40

Everybody wondered what they were going to do when they advertised that fourteen marks would be paid for every load of common thistles. But the thistles are being made into cloth. Hair is also made into cloth. Coffee grounds are also collected, but it has not been decided how they shall be used.

When the clocks are changed in the summer, it saves a great amount of gas, and since the first of January, 1917, all the stores must close at 7 o'clock instead of 8. All electric light advertisements are prohibited, and all theaters and public places close earlier.

In the city of Hanover, on account of the scarcity of water, the water is shut off from the bath rooms, and no one can take a bath. In Copenhagen there is also a scarcity of water, and when I was there the water all over the city was shut off between two and four o'clock in the afternoon.

This coming winter people will be urged in every way to save coal, and if possible to heat only one or two rooms. They have plenty of coal but no way of delivering it, and last winter people had to go down to the freight yards and fetch the coal themselves. I often saw fine-looking ladies wheeling coal in baby carriages. Baby carriages are used for hauling everything, and they are very practical.

In every way paper is being saved, especially wrapping paper. Every woman has her bun bag, and when she goes to the bakery shop to buy buns she takes it with her. I have seen men buying buns 41 in stores, and they nearly always have their own paper bag with them. Bread is just wrapped in the middle of the loaf, and if you don't take your own bag with you for eggs, you will have to carry them home in your hand.

In the markets nothing is wrapped. Every German woman has what she calls her Tasche. It is a black bag with handles and it is used in preference to a basket. Everything that is bought in the market is put into this bag unwrapped. If you buy anything that is too large to put into the bag you have to carry it home in your hand unwrapped. Rhubarb is carried in this way. Meat is first wrapped in a thin piece of wax paper and then in a newspaper. Wherever it is possible, newspapers are used for wrappings. We were never fussy about carrying a newspaper bundle in Germany, we were glad we got the newspaper. One night a friend of mine, an American girl, came to stay all night with me, and as we had only two quilts, she had to bring her own quilt with her. She had no paper big enough to wrap the quilt, so she just carried it in her hand. The people on the street car and on the street did not even stare, they merely thought that she was a good German woman who was sparing of paper for the Vaterland.

Collecting Old Automobile Tires.

In the department stores they do not use string on small packages, and on large packages they tie the string only one way around. If the purchase is a very small object like a spool of thread or a 42 paper of pins, it is wrapped in the bill. Many people carry their own wrapping paper with them and it is always wise to carry a piece of string. None of the department stores will deliver anything that costs less than five marks, and notices are posted everywhere asking people to carry their purchases home with them. Only one store, Borchardt's grocery store, still wraps up things as nicely as in days of peace, and when you buy anything there you are sure that the package will not come open on the street. Now they have invented a new kind of string made out of wood. It is very strong but hard to tie.

Since the very beginning of the war no one in Germany has been allowed to run his own automobile on account of the scarcity of rubber tires and gasoline. All the automobiles displayed in the store windows have tires made of cement. This is just done to make them look better. All the tires have been taken over by the military authorities. No one is allowed to ride a bicycle with rubber tires without a permit. They have invented two kinds of tires for substitutes. One kind is made of little disks of leather joined in the middle, and the other kind is made of coiled wire. Both these tires are advertised, and the advertisements read: "Don't worry, ride your bicycle in war time. Get a leather disk tire; then you don't need a permit."

For everything that is scarce in Germany they have a substitute and in this line German ingenuity 44 seems to have no end. They have a substitute for milk called Milfix. It is a white powder, and when mixed with water it looks like milk. It can be used in coffee or for cooking. The funny part about Milfix was that when it first came out everybody scorned it, but all of a sudden there was hardly any real milk to be had, and Milfix was put on the Lebensmittel food card, and one could only buy a small quantity of it. Then everybody was just wild to get a little bit of the precious stuff.

Then they have egg substitutes. Some brands of it are in powder form and other brands are like yellow capsules. They are very good when mixed with one real egg and make very good omelet. Then there is the meat substitute. It comes in cans and is dark brown in color. It is some kind of a prepared vegetable. It looks like chopped meat and it is said to taste like meat. They have a hundred different varieties of substitutes for coffee, and without any exception all brands of Kaffee-Ersatz are very bad.

The most unique thing on the market is the "butter stretcher." That is what they call it. It is a white powder, and they guarantee that when it is mixed with a quarter of a pound of real butter it will stretch it to half a pound. We bought some of it but we never had the courage to try it on a quarter of a pound of real butter; but many boarding-houses used it.

Every day something new bobbed up on the market. 45 One of the finest things was Butter-Brühe and Schmalz-Brühe. It came in cans the half of which was either butter or lard and the other half was broth. It was fixed this way so it did not come under the butter card or the fat card. The cans weighed a half pound and sold for five marks. It was foreign goods from either Holland or Denmark.

Last spring there appeared on the market great quantities of "Irish stew" in cans. The Germans stood around it wondering. What was Irish stew? None of them had the slightest idea. But finally they bought it, for they said, if it was Irish it must be good. They have a substitute for sausage made out of fish. It is awful stuff with a lingering taste that lasts for days.

They have substitutes for leather, rubber, and for alcohol. They have what they call a spiritus tablet, and it can be used in lamps. It is used by the soldiers in the field. As matches are very expensive they have a small apparatus of two iron pieces that when snapped make a light. As soap is very scarce in Germany hard-wood floors are cleaned with tin shavings. The shavings are rubbed over the floors with the feet, the workers wearing felt shoes.

A Collection of Copper.

All over Germany soap is used very sparingly. Clothes are put to soak a week before wash day and each day they are boiled a little. This plan saves all the hard rubbing, and when the clothes are taken out of the water the dirt falls out of them. 46 They don't use wash-boards in Germany. Pasted everywhere in Berlin are posters which say, "Save the soap." They say to shake the soap in hot water and never let it lie in the water and always keep it in a dry place.

Most stores will sell only one spool of embroidery floss to one person at a time. If you want a second spool you must go the next day. This restriction is very hard on the German woman who loves to do fancy work.

We saved everything. When we boiled potatoes we saved the water for soup or gravy. It had more strength than clear water. We never ate eggs out of fancy dishes with grooves in them, as too much of the egg stuck in the grooves. We served everything from the cooking kettle right on our plates, so that no grease would be wasted. Many restaurants also did this, and what you ordered was brought in on the plate that you ate from. A great many people used paper napkins for every day. This saved the linen and the soap. We never threw out our coffee grounds but cooked them over and over. We weren't used to strong coffee, and these warmed-over grounds were much better than Kaffee-Ersatz.

Some people cooked rhubarb tops in the same way you cook spinach. It makes a very good vegetable. We took the pea pods from the fresh peas and scraped them and cooked them with the peas. These are really fine. It is a well-known Polish dish. The first year we were in Berlin we could 48 get corn starch, and we used this for thickening food instead of flour.

One of the funniest things was that you could not buy an orange unless you bought a lemon. This worked two ways. The oranges were saved and the storekeepers got rid of the lemons. I have never seen anything like the quantity of lemons in Germany—millions of lemons everywhere. Lemons, radishes and onions were three things that you could buy any time without a card and without standing in line.

Since the war, hundreds of war cook books have been printed. They are generally very practical and give excellent recipes for making cakes without butter or eggs or even flour, using oatmeal instead. They tell how to make soup out of plums, apples, pears, onions and fish. And they contain menus with suggestions of things to have on the meatless days. They save the puzzled housewife's brain much worry.

Last Christmas in Germany was known as the Christmas of a single candle, and most of the Christmas trees had only one light on the top. One has no idea of the tremendous sacrifices these people are making for their country. 49

In Germany I sometimes had to go to three or four different stores before I could get a spool of silk thread. Leather is so expensive that only the upper-class burgher will be able to have real leather shoes this winter; and starch is twenty marks a pound. But after all, no German will go to work with an empty dinner pail.

The German Food Commission is the most uncanny thing in all the world. Like magic it produces a substitute for any article that is scarce, it has everything figured out so that provisioning shall be divided proportionately each week, and just what each person shall receive, for everybody does not receive the same amount of food in Germany. For instance, a man or woman who does manual labor gets more bread than a man or woman who works in an office; people over sixty years get more cereals, and sick people get more butter and eggs. These people get what they call Zusatz cards, besides their regular cards.

Every one in Germany is getting thin, and the German dieting system proves that much worn-out 50 statement that "we eat too much," for nine out of every ten Germans have never been so well in their lives as they have been since the cards have been introduced. You feel spry, active and energetic, and the annoyance is mental rather than physical, for one is constantly thinking of things to eat.

Woman Selling Ices.

The ones that are really hurt by the blockade are the growing children, and the thing that they lack and long for is sweets. Before the war, one never realized what an important role candy played in the game of life. The food commission recognizes this, and very often chocolate and puddings are given on the cards of children under sixteen years of age.

While food prices have been soaring all over the world, prices in Germany are almost down to normal level, for anything that you buy on the cards 51 is extremely cheap, and everything that is any good is sold on the cards. Everything that is sold ohne Karte, or without a card, is either not good or so expensive that the ordinary person cannot afford to buy.

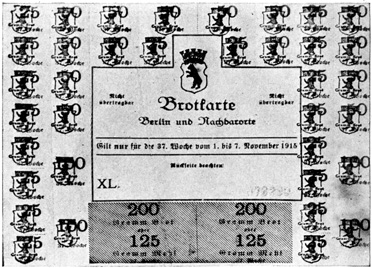

When I first came to Germany in October, 1915, there was only one card, and that was the bread card. This card was divided off in sections with the numbers 25, 50 and 100 grams. At that time the whole card was 2100 grams for each person each week. Later it was reduced to 1900 grams, and on the first of May, 1917, to 1600 grams. This last reduction was a courageous thing for the bread commission to do at this time—one of the worst months of the year before the green vegetables come in—and in Berlin a couple of thousand workers from a factory gathered on Unter den Linden. They stayed two hours, broke two windows, and then went home pacified at a pound of meat a week more and more wages.

On the bread card it takes a 50 gram section to buy a good-sized roll, a whole card to buy a big loaf of black bread, and half a card to buy a small loaf of bread. After the bread card was reduced no buns were allowed to be made in Berlin, although in the other cities they have them. Instead, they had what they called white bread, but it was almost as black as the black bread, and when buying one had to ask, "Is this white or black bread?" I thought that the bread was very good, and it was of a much 52 superior quality to what I got in Sweden where the bread card is of a less number of grams than in Germany. At the bottom of the German bread card is the flour ticket, and it allows one the choice of either 250 grams of flour or 400 grams of bread. I came out very well on my bread card, for even when I lived in a boarding-house I kept my card myself and I took my bread to the table with me. When people are invited to a meal they always take their bread and butter with them.

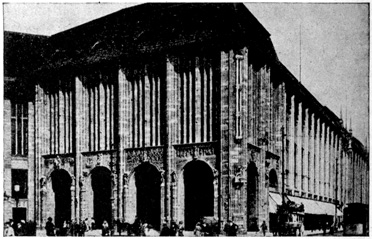

A Store in Charlottenburg, a Suburb of Berlin.

After the bread card the next food restriction was the two meatless and fatless days a week. On Tuesday and Friday no butcher was allowed to sell meat, and no restaurants or boarding-houses were allowed to serve meat. Monday and Thursday were the fatless days. The butchers were not allowed to sell fat, and the restaurants were not 53 allowed to cook anything in grease. On Wednesday no pork was allowed to be sold.

Until after Christmas there were no other cards, but along in December the butter began to be scarce, and the stores would sell only a half pound to each person, and the people had to stand in line to get that half pound. These butter lines were controlled by the police, and it was no joke standing out in the cold to get a half pound of butter. But after Christmas came in rapid succession the butter card, the meat card, the milk card, the egg card, the soap card and the grocery card. These cards have regulated everything and have stopped the standing in line for articles.

At first the butter card called for half a pound of butter each week, but now it varies. Then it wasn't a separate card, but the center of the bread card was stamped for butter. Now each person gets either 60 grams of butter and 30 grams of margarine, or 80 grams of butter. You must buy your butter in a certain shop where you are registered and you can buy no place else. This is also true of sugar, meat, eggs and potatoes.

At first the meat card was only for home buyers, and the restaurants could serve as much meat as they liked, but soon it was seen that this was not fair to the people who eat at home. A card was issued that was divided off into little sections, so that the meat could be bought all at once or at different times. On the first of May, 1917, the meat card was 54 increased by one-half, and every one is getting 750 grams of meat instead of 500 grams. Here the food commission made a mistake: they should have given out more meat in the cold months and have kept more flour for spring, but instead they increased the meat card in May and lowered the bread card.

One of the First Bread-Cards.

Another mistake that the food commission is making is allowing scandalous prices to be charged for fowls. Fish, chickens, geese and turkeys are bought without cards, but the prices are so high that few people can afford to buy them, and the birds are lying rotting in the store windows. Those birds are undrawn to make them weigh more. A medium-sized turkey or goose costs anywhere from 55 sixty to one hundred marks, and a chicken runs about thirty marks.

The milk card was among the first cards, and only sick people and children get milk. The babies get the best milk and the older children get the next best, and after they are served the grown-ups get what is left. Adults have no milk card.

The sugar card varies, but one gets about 1¾ pounds of sugar each month. At preserving time people are given extra sugar and saccharine on the grocery card. The potato card varies. First it was seven pounds a week for each person, then it was reduced to five and then to three, and then it was raised to five again. This was the only card on which we sometimes did not get our allowance, and when there were not enough potatoes for the cards we could get extra bread on our potato card. At first some of the potato cards were red and others blue. The red cards were good on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Sunday, and the blue ones were good on Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday. Now no potatoes are allowed to be put into the bread.

The egg card came in the summer of 1916, and for a long time afterward it was possible to get all the eggs you wanted in restaurants without a card, but now one must have a card there as well, even if you order an omelet or an Eierkuchen, a pancake of which the Germans are very fond.

The Lebensmittel or "grocery" card is a very 56 important card, and it is for buying such things as noodles, rice, barley, oatmeal, macaroni, white cornmeal and cheese. Then they have other cards for buying oil, saccharine, matches, sardines and smoked fish. Fresh fish is without a card. Each week the stores have numbers hanging up in their windows telling what can be bought that week, like "Rice on Number 13" or a "Pudding on Number 6." It is also printed in the newspapers and on the advertising posts, and sometimes you must be registered for the things and can buy them only in a certain store.

An Asparagus Huckster.

On the first soap cards, you could get every month a cake of toilet soap, a cake of laundry soap 57 and some soap powder, but now one can get only 50 grams of either kind of soap and 250 grams of soap powder each month. Soap was one of the hardest things to get, and a cake of real soap sells from five to ten marks a cake. We never thought of taking a bath with soap but used it only on our faces. They have what they call "War Soap," and it can be used on the hands, but if it drops on your dress it leaves a white spot. If you want to give a real swell present to any one in Germany just send a cake of soap.

I always said that when coffee came to an end in Germany the Germans would be ready to make any kind of a peace. How could a German live without coffee? But last summer the coffee gave out and instead of complaining they took to drinking Kaffee-Ersatz, or "coffee substitute," with the same passion that they had lavished on real coffee. It is the most horrible stuff any one ever tasted with the exception of the substitute they have for tea, but the Germans say they like it. They have cards for Kaffee-Ersatz, and each person gets a half pound a month.

In the cafés in the summer of 1916 they were still serving real coffee with milk and sugar. Then suddenly the waiters commenced asking the patrons if they wished their coffee black or with cream, and then later they asked if you wanted the coffee sweet, and so they brought it, putting in sugar and milk themselves. A little later you did not get sugar 58 but two little pieces of saccharine were served, and now they have a liquid sweet stuff that is used. They do not serve real coffee any more, but most restaurants still serve milk. The famous Kaffee mélange, or coffee with whipped cream, was forbidden at the beginning of the war.

When I left Germany they had no beer or tobacco cards, but there was talk about them. The beer restaurants receive only a certain amount of beer each day, and when this is gone the people must wait until the next day. Most beer halls serve only two glasses to each person. In Munich, because of the shortage of beer, some of the beer halls do not open until 6 o'clock at night, and at 4 o'clock the Müncheners gather at the doors with their mugs in their hands, patiently waiting. Sometimes they knock the mugs against the doors to a tune. Munich without beer is a very sad sight!

In Berlin some of the restaurants will serve beer only to people who can get chairs, but this does not faze the clever Berliners, and when they want their beer they bring camp stools with them, and then they are sure to have a seat. It is forbidden to make certain kinds of fine beers because they take too much malt and sugar. None of the beer is as good as in times of peace, but the Germans have forgotten the delicacies of the past, and they live in the food ideals of the present, and they smack their lips and say, "Isn't the beer fine to-night?"

From August 1916 until March 1917 it was forbidden 59 to sell canned vegetables. They were being saved up for the spring months. The store windows were decorated with glass jars filled with the most wonderful kinds of peas, beans and asparagus. I always felt like smashing the window and stealing the stuff, but the Germans only looked at it admiringly and said, "It will be fine when the vegetables are freed."

Everything on the cards is at a set price, and the dealers don't dare to charge one cent more; even the prices of some things not on the cards are regulated. For instance, this spring no one could charge more than one mark a pound for cherries, and many of the cafés had to cut their cake prices. The police got after Kranzler, the famous cake house, and it had to reduce all its cakes to twenty pfennigs each.

When I was in Dresden in May, 1917, I ate elephant meat. An elephant got hurt in the Zoo and had to be killed. A beer restaurant bought his meat for 7000 marks, and it was served with sauerkraut to the public without a card at 1.30 marks. It tasted like the finest kind of chopped meat, and the restaurant was packed as long as the elephant lasted.

The food question is not the same all over Germany, and in Berlin, Dresden, Hamburg and Leipsic they have less than in other places. Bavaria, the Rhine Country and East Prussia are far better off, and in some of the small villages they do not even have a bread card.

One of the hardest things to get is candy. In 60 Berlin one can buy chocolate for sixteen marks a pound, but in Dresden it is very cheap because it is bought on the card. The candy is bought on the grocery card and one gets a half pound every two weeks. Candy lines are the only kind of lines that one sees now in Germany.

One card I forgot to mention is the coal card that will be issued for the coming winter. There is no scarcity of coal, but there are no people or cars for delivering. The people will be given three-fourths as much coal as they formerly consumed.

In times of peace eating in a German restaurant was notoriously cheap, and one could get a menu of soup, meat, potatoes and dessert for 90 pfennigs, and in Munich for 80 pfennigs. Now these same restaurants charge 1.75 marks, that is, twice as much; but even then food is cheaper than in America. Before the war some of the restaurants charged extra if you did not order anything to drink, but this is now done away with.

Anything can be bought without a card if you know how to do it. The government tries in every way to stop this selling, and although the fine is very heavy for selling ohne Karte, it goes on just the same. We always managed to get things without a card. Our janitress got coffee for us at 9.25 marks a pound, our vegetable woman gave us extra potatoes, and we could always get eggs. On the card an egg cost 30 pfennigs and without a card we paid anywhere from 50 pfennigs to 1 mark. The 61 hardest thing to get without a card was sugar, for the food commission has an iron hand on the sugar, but we got it for 2.50 marks a pound. On the card it was 30 pfennigs a pound. It is said that butter could be bought for nine marks a pound without the card, but we never tried to get it.

The police sees that every one gets his share of food. If a woman holds a servant girl's rations from her, the girl can report it to the police and the woman is fined. In a boarding-house when the potatoes are passed around the landlady tells you whether you can take two or three potatoes, or one big potato and one small potato. The food conditions are not always comfortable, but the food commission has the things divided off so they will last for years. 62

Reading over the food restrictions, one does not get a very clear idea of what we really ate in Germany, so I have made out a menu that was possible in the month of April, 1917. April is, of course, one of the hardest months of the year because it is just before the green vegetables come in and the winter supplies are gone. In this month, however, we could buy canned goods which were forbidden during the winter months, and each person was allowed two and one-half pounds of canned goods a week.

The menu as I have written it includes only things which are bought on a card or without a card, but no restricted food that has been bought underhand without a card as everybody does. It does not include any of the expensive articles like chicken, goose, or fresh vegetables which the better middle class have, and it does not include the canned vegetables, fruit and meat which all German families have in their supply cupboard.

When we kept house, we obtained many things from friends, and when my mother came back from 63 a trip to America, she brought with her forty pounds of meat, bacon, ham and sausage, eighteen pounds of butter, sugar, coffee, canned milk, chocolate, rice and flour. Some of this she bought in Denmark, and the rest she brought over from America. In January, 1917, I made a trip to Belgium, and while the Germans were allowed to take only ten pounds of food out of Belgium we had special permits, and I brought back a lot of food. Most people had crooked ways of getting things, and we were all as crooked as we had a chance to be.

Nothing was allowed to be sent from Poland to Germany, but a Polish girl I knew made a trip home to Warsaw, and going over the frontier she made "a hit" with the man that takes up the "louse tickets." You cannot go from Warsaw to Berlin unless you show a ticket stating that you are not lousy. The girl's mother in Warsaw sent the "louse soldier" the food, and he relayed it to Berlin. Once the soldier came to Berlin on a furlough and he called on the Polish girl. He was an awful-looking specimen, but he was served the finest kind of a dinner.

In April we still had 1900 grams of bread, but I have made out the menu with 1600 grams as it is now. Sixteen hundred grams of bread is 32 slices of 50 grams each, but I have allowed five slices of bread a day, for the bread at supper was always cut thin and often weighed only 40 grams. Most families weighed the bread for each person and then 64 every one got his share. People who ate in restaurants always watched their bread rations, for the waiters were liable to bring short weights. If you were in doubt whether you were getting enough in a restaurant, you could demand to have the bread weighed before you. This sometimes stirred up a lot of trouble, and rows often occurred.

We had five pounds of potatoes a week. This makes 2500 grams, and in the menu I have allowed 300 grams of potatoes seven times a week. As this makes only 2100 grams, this leaves 400 grams for the peelings. The omelet for Monday's menu could be made out of real eggs, but the pancakes for Sunday would have to be made out of egg substitute.

As we had 750 grams of meat a week, I have allowed 130 grams four times a week which makes 520 grams, and this leaves 230 grams for sausage. Graupen that I have mentioned is a large coarse barley, and when I say turnips I mean what they call Kohlrüben—we sometimes call it rutabaga. We ate this vegetable constantly during the spring of 1917. Most people hated it, but it was fine for filling up space. Dogs were fed almost entirely on it. When I was in Dresden I went to the Zoo, and there they had packages of carrots and Kohlrüben for sale for feeding the monkeys. The monkeys were hungry and they gobbled up the carrots, but they absolutely refused to eat the Kohlrüben, and when they were handed a piece they threw it down in disgust. 65

This menu was typical of the German pension or boarding-house, where the landlady stayed well within the limit of the cards because the things on the cards were cheap. For breakfast we always had the same things—coffee substitute, two pieces of bread, four times a week two pieces of sugar, and three times saccharine, four times a week butter and three times marmalade. Even in peace times Germans eat only coffee and rolls for breakfast. At 11 o'clock they have a second breakfast, and this consisted sometimes of oatmeal with salt and once in a while a piece of bread with jam, then they could not have so much for supper. In the afternoon at 4 o'clock they always have coffee substitute and cake, generally made without eggs or butter and sometimes without flour, using oatmeal or white cornmeal for flour.

| DINNER | SUPPER | |

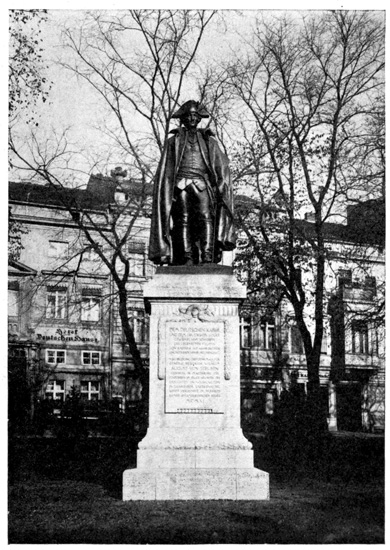

|---|---|---|

| MONDAY | ||

| Bouillon. | 3 pieces of bread. | |

| 300 grams of potatoes, scalloped with mushrooms and milfix. | 62½ grams of sausage. | |

| Omelet. Asparagus. | ||

| Carrot salad. | Pickles. Lard instead of butter. | |

| White cornmeal with fruit juice. | Tea or beer. | |

| Wine. | ||

| TUESDAY | ||

| Brown flour soup. | 3 pieces of bread. | |

| 130 grams of beef. | 300 grams of potatoes | |

| 300 grams of potatoes. | Dried fish. Stewed onions | |

| Canned beans. Cake. | Tea. Beer. Marmalade | |

| Wine. 66 | ||

| WEDNESDAY | ||

| Noodle soup. | 3 pieces of bread | |

| Fish. | 62½ grams of sausage | |

| 300 grams of potatoes. | 300 grams of potatoes | |

| Fried turnips. | Graupen with bouillon | |

| Gelatine. | Radishes. Butter | |

| Wine. | Tea. Beer | |

| THURSDAY | ||

| Onion soup. | 3 pieces of bread | |

| 130 grams of veal. | Bouillon | |

| Rice. Canned peas. | Canned spinach with 1 egg | |

| Cake. | Radishes | |

| Wine. | Tea. Beer | |

| FRIDAY | ||

| Vegetable soup. | 3 pieces of bread | |

| Graupen with stewed fruit. | 300 grams of potatoes | |

| Asparagus. | Sardines | |

| Chocolate pudding. | Vegetable salad. Butter | |

| Wine. | Tea. Beer | |

| SATURDAY | ||

| Asparagus soup. | 3 pieces of bread | |

| 130 grams of pork. | Macaroni and cheese | |

| 300 grams of potatoes. | Turnip salad | |

| Stewed dried apples. | Marmalade | |

| Pudding. | Pickles | |

| Wine. | Tea. Beer | |

| SUNDAY | ||

| Plum soup. | 3 pieces of bread | |

| 130 grams of beef. | Bouillon | |

| 300 grams of potatoes. | Egg pancake filled with cranberries | |

| Turnips. | Butter. Radishes | |

| Lemon pudding. | Tea. Beer | |

| Wine | ||

Since the war many war cook-books have been printed, and these books contain recipes for dishes that can be made with things now obtainable in Germany. Some of these recipes are very good, 67 and some of them are simply awful. I will give you some of the most used and popular ones.

BEER SOUP.

2 quarts of beer brought to a boil.

1 egg well beaten.

2 tablespoonfuls of sugar.

Flour to thicken.

Boil and serve hot.

PLUM SOUP.

½ pound of plums boiled in a quart of water and strained.

2 tablespoonfuls of sugar.

½ cup of oatmeal.

Boil and serve cold.

APPLE SOUP.

3 cups of apple sauce sweetened.

2 bouillon cubes.

3 cups of water.

Boil and serve hot.

(Pear soup is made in the same way.)

ONION SOUP.

6 large onions boiled and put through a colander.

2 bouillon cubes.

1 quart of water.

Flour to thicken.

Boil and serve hot.

POTATO AND CABBAGE PUDDING.

(This is used as a meat substitute.)

1 head of cabbage boiled thirty minutes.

6 sliced potatoes.

Boil all together until soft.

1 teaspoonful of lard, heat and add flour until a brown gravy is made. Add salt and pepper. Stir into potatoes and cabbage and serve hot.

BAKED VEGETABLES.

½ head cabbage.

½ rutabaga sliced.

4 potatoes sliced.

2 bouillon cubes, flour thickening and seasoning.

Mix together and bake in oven for one hour.

68

STUFFED CABBAGE.

1 head of cabbage boiled one-half hour.

1 cup of chopped meat fried in fat.

Quarter the cabbage, scooping out the heart.

Fill the space with meat.

Bake in an oven ten minutes and serve hot.

CUCUMBERS WITH MUSTARD SAUCE.

3 large cucumbers halved lengthwise and boiled.

1 quart of water boiled with mustard to taste and thickened with flour—sweetened.

Pour the mustard sauce into a deep dish and lay the hot cucumbers on top.

POTATO DUMPLINGS WITH STEWED FRUIT.

6 large raw potatoes grated.

1 egg or 2 egg substitute powders.

1 cup bread grated and browned.

Add enough flour to thicken and form into dumplings.

Boil for half an hour.

Serve with hot stewed fruit—peaches, apples, apricots or plums.

DROP CAKES WITHOUT EGGS, SUGAR OR MILK.

½ cup walnut meats.

2 egg substitutes.

½ cup milk substitute.

½ teaspoonful saccharine.

1 tablespoonful baking powder.

1 cup flour.

Add a little cinnamon. Bake as drop cakes.

Flour the baking pan instead of greasing it.

OAT MEAL CAKES.

1 egg.

½ cup milk substitute.

½ teaspoonful saccharine.

Oatmeal to thicken.

1 tablespoonful baking powder.

Beat together and bake as drop cakes.

RAISIN BREAD.

½ cake yeast.

1 cup potato water.

2 tablespoonfuls of raisins.

1 pound of flour.

Set sponge at night and bake one hour.

When war was first declared all the theaters and amusement places in Berlin were closed, and it was not until after Christmas of that year that they were opened again. Now everything is open except the dance halls, for dancing is prohibited during the war. The famous resort "Palais de Danse" is closed up and its outside is all covered with posters asking for money for the Red Cross.

The theaters in Berlin are very well attended. As many times as I went to the opera, which was quite often, every seat in the house was taken. The greater part of every audience are soldiers who are glad to spend some portion of their furloughs forgetting the horrors of war and life in the trenches. The operas are as brilliant as before the war, but many of the young stage favorites are missing, for even the matinee idol must take his turn at the front. Several of the popular actors have been killed.

One can always hear the French and Italian operas, and at concerts the music of the great Russian 70 composers. They do not prohibit the music of enemy composers, and one can hear Verdi, Mascagni and Gounod. However, "Madame Butterfly" and "Bohème" were never given to my knowledge. I do not know whether it was because they had no singers for these operas which are great favorites, or whether it was because of the nationality of the composer.

A Boat Race near Berlin, April, 1916.

Just before I left Berlin I saw a wonderful production of "Aïda," and the principal singers were Poles from the Royal Opera House in Warsaw. The singers were received with the wildest enthusiasm. All the cast except the Poles sang in German, and the Poles sang in Polish. The duets sounded very funny. Two of the Polish singers were invited to come and sing permanently in Berlin. They both declined. The man, who has one of the most magnificent 71 voices I ever heard, because he loves Warsaw too much to leave it, and the woman because she did not want to be tied up in Berlin with a five-years' contract, as she wants to come to America as soon as the war is over. There is more or less a movement in Germany to taboo the German singers who are in America, and they also want to prevent all their new young singers from coming to us. It will be a very hard task, for America is the aim of every German singer, and no feeling of patriotism will keep them at home.

Since the war many new stars have arisen, and many new operas have been played. From Bulgaria comes a young singer by the name of Anna Todoroff, and she has taken Berlin by storm. Several boy wonders have sprung up, the greatest being a little boy from Chili, Claude Arrau.

The greatest triumph of last season was Eugen d'Albert's new opera Die toten Augen, or "The Dead Eyes," and it was played several times a week. The music of the opera is lovely, entrancing, but what a strange theme—a blind woman who is married to a man she has never seen, prays unceasingly for her sight so that she can see her husband. At last her prayer is answered, and when her eyes are opened she beholds a beautiful man by her side whom she believes to be her husband. She makes love to him, and he loves her in return. The husband who was absent when his wife's sight was restored returns, and he finds his wife's lover. 72 He challenges the man to a duel and kills him. The woman is distracted by grief. She no longer wishes to see, so she goes out and sits in the sun with her eyes wide open. She sits there until her very life is burned out. That is the end. D'Albert is a Belgian and either his fourth or fifth wife was Madame Carreño, the pianist, who died lately. His present wife is an English woman.

An Art Exhibition Showing Fritz Erler's Picture of the Crown Prince.

An American named Langswroth has written a very successful opera called "California." Perhaps it will be played in America. An old opera that was played frequently last winter in Berlin was Meyerbeer's opera "Die Afrikanerin." In spite of its age it was very popular.

The concerts are always well attended in Berlin; and Strauss, Nikisch and von Weingartner are 73 very popular. Each conductor has his following. Last winter Lillie Lehmann gave a concert. She is sixty years old, and her voice is still very beautiful. She does not sing very often in public and spends most of her time writing songs and teaching a few chosen pupils.

One misses the great foreign stars who always came to Berlin each season, but still they have the great artists Joseph Schwartz, Conrad Ansorge, Clara Dux, Slezak, Emil Sauer, Karl Flesch, Arthur Schnabel and scores of others.

The character of the plays has more or less changed since the war, and while comic operas are still being given, the most popular shows are of a more serious character. The greatest favorites are Strindberg, Ibsen, Brieux, Björnsen, Shaw, Wedekind and Shakespeare. A German loves Shakespeare much more than an American or an Englishman does, and last winter, all winter long, Max Reinhardt gave Shakespeare at the Deutsches Theater. In spite of Shakespeare's English origin, the plays were very well attended, and yet I do not think the audience was like the German girl that Percival Pollard told about. He made her say, "What a pity that Shakespeare is not translated into English. I should think that they would like him in London."

The play that caused the greatest sensation in Germany last season was a tragedy called "Liebe," or "Love." It was a grewsome tale of two married 74 people. It was full of the sordidness, the horrible actualities of life. I lived at the same boarding-house with the actress that took the part of the wife in the play, Frau Anna, the main role. She was quite a frivolous young German girl, but she splendidly managed the part of a woman that had been married nine years.

A Boat Club in the Grunewald near Berlin.

Moving picture shows are not as popular in Germany as in America because of the high prices. In Germany it costs as much to go to a "Kino"—that is what they call a "movie"—as it does to sit in the gallery at the opera. For shows no better than our five-cent shows we had to pay two marks, and one can sit in the gallery at the Charlottenburg Opera House for ninety pfennigs.

They have their "movie stars," and one of the 75 greatest favorites is an American girl named Fern Andra. When I left Berlin her films were still drawing great crowds, America's entrance into the war having made no difference. They do not have Charlie Chaplin in Germany. They know him in Norway, but so far Germany has escaped. One German editor wrote, "Gott sei Dank, the war has prevented us from going Chaplin mad."

As a whole the German "movies" are not nearly so good as ours, they cannot compare with our wonderful productions. The only part that is better than ours is the music, and they always have fine orchestras of from ten to thirty men. Here in America we just drop into a "movie," but in Germany it makes a special evening's entertainment. Most of the "kinos" have restaurants attached, and in all "kinos" you must check your wraps. I often stayed away from shows just because I hated the idea of going to the Garderobe and checking my wraps.

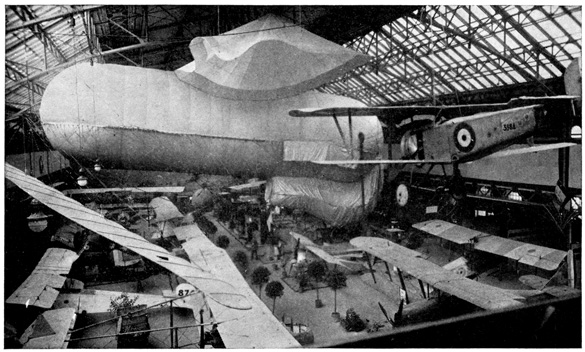

Booty Exhibition in Berlin. Captured Air-Ships.

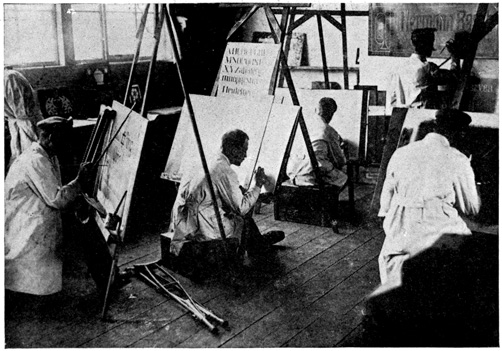

I saw a great number of fine art exhibitions in Germany. Germans consider an art exhibition as one of the necessities of life. Cubist art has rather gone out of date, and war art has taken its place. Such stirring pictures as these war artists have produced! Most of the best German artists have been to the front sketching, and the war productions of such artists as Fritz Erler and Walther Georgi are some of the most wonderful paintings I have ever seen. Weisgerber was another artist who has 76 made blood-stirring war pictures. He was a German officer and was killed a year ago in France. He was very young, and his work was full of great promise. His work was much seen in Die Jugend.

I saw the great Berlin exhibition of art last fall. It was not nearly so interesting as the great international exhibitions that were held in Germany before the war. It was monotonous, and yet I have never seen an exhibit where so many pictures were sold. I saw hundreds and hundreds of pictures marked Verkauft.

It is surprising the number of art works of all kinds that are being bought in Germany. I often used to go to Lep's Auction Rooms where all kinds of art works were sold, at auction. The place was always crowded with bidders, and the bidding was fast and high. I went one day to a stein sale and saw 119 steins sold for nearly 4000 marks. I am no judge of porcelain, but it seemed like spending a lot of money. Another day I went with a man I knew, a German. For 100 marks he bought three odd tea-pot lids. He thought he had a great bargain, but I could not see it.

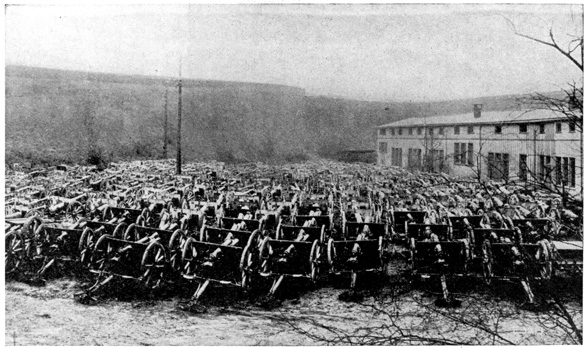

Booty Exhibition in Berlin. Captured Cannon.

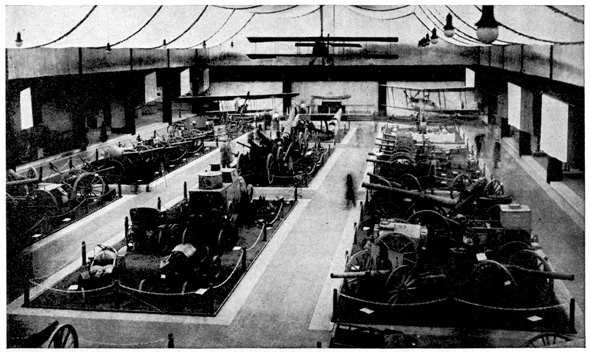

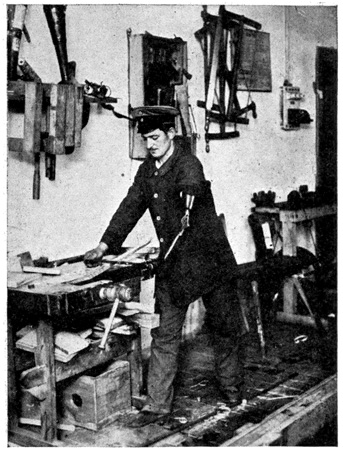

Germany has always been the land of Ausstellungen, or "exhibitions," and the war has only served to increase the number. In every city I was in during the two years I saw dozens of Kriegs-Ausstellungen advertised. Every city has had exhibitions of artificial arms and legs with demonstrators showing how they work. Then they have 78 displays of uniforms, guns, aeroplanes, ships and photographs. In Berlin they had an exhibition of the forts around Verdun. It was wonderfully made—everything in proportion, with tiny soldiers, wagons, wire entanglements etc. The greatest show they had when I was there was the "Booty Exhibition" in which all kinds of captured war material were displayed.

The Germans are very fond of walking, and the war has not decreased the pleasure which they find in this pursuit. Before the war the walkers did not carry their lunch with them, but now they must if they want to get anything to eat; and every afternoon you can see crowds of people starting out, each with a little package of lunch. The Berliners like to go to the Grunewald where they stop at a little inn and order a cup of Kaffee-Ersatz, eat their sandwiches, and feel they are having a very nice time.

Sitting in a café with a cup of cold coffee before them, always has been and always will be the favorite amusement of the German people. Here they can read the magazines and papers and look around. Most Germans do not entertain their friends at home but meet them at a café, and each person pays for what he orders.

All through the war they have boat and track races, and these sports are very popular. Before the war they had aeroplane exhibitions, but these are not held any more. All the hospitals have concerts 80 and moving picture shows for the wounded soldiers.

The main amusement of the people now is talking about things to eat. A man I know in Dresden meets eight of his cronies at a Stammtisch every Saturday night. Before the war they discussed politics, art, music, literature and science, but he says now they talk only about eating. In March and April when we had that awful run of a vegetable called Kohlrüben, the man I know said his Stammtisch was going to get out a cook-book for Kohlrüben, for they knew twenty-five different ways to cook them! 81

It has been said that the sign Verboten was the most seen sign in Germany, but now that sign has a rival in Ohne Bezugsschein, which means "without a clothes ticket." All the store windows are decorated with these cards and merchants are pushing forward these articles because they are more expensive than the articles which require a card, and most people would rather pay a few marks more than go to the trouble of getting a card.

Along in May, 1916, there were rumors of a ticket for clothes, but the people only laughed, "How could there be a ticket for clothes?" they asked and "What will we do if our clothes wear out and we can't get a ticket for any more?"

On the 10th of June the ordinance was published, and it went into effect on the 1st of August. Now the ticket is in full swing, and one must have a ticket to get all the articles of wearing apparel and household things that are not marked Ohne Bezugsschein.

The Bezugsschein was not originated to make things uncomfortable for people in general, but to 82 protect the people who are poor and to keep the rich people from buying up the cheap useful articles that poorer people must have for winter. At first it was only cheap useful articles that were on the card, and articles of clothing that were over a set price could be bought without a card, but now many expensive things are on a card as well, and no matter what the price is, a man or a woman can have only two woolen suits a year.