Copyright 1913 and 1914, by McBride, Nast & Co. Second Printing September, 1914 Published October, 1914 |

TO MY FRIEND EDWARD FRANK ALLEN |

| PAGE | ||

| I | The Cottage in the Pines | 13 |

| II | "Lord Chesterfield" | 31 |

| III | The Invisible Guest | 49 |

| IV | Son Robert's Letter | 63 |

| V | The Little Hermit | 79 |

| VI | From the Shadow of the Pine-boughs | 91 |

| VII | "Lady Ariel" | 103 |

| VIII | The Lady of the Fire-glow | 117 |

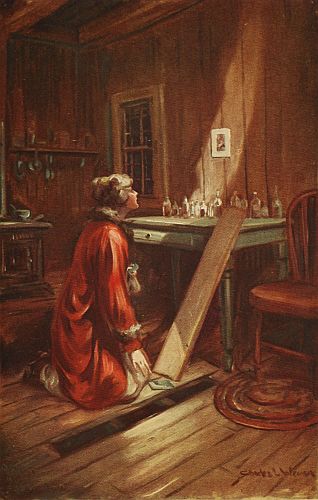

| The ever-busy crutch fell unheeded to the floor and Aunt Cheerful Loring fell sobbing to her knees | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE |

|

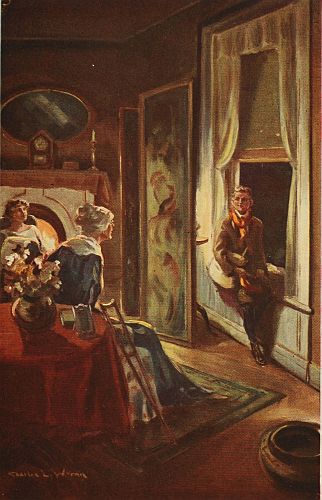

| The boy seated himself upon the window sill and doffed his dripping cap with the air of a gallant | 34 |

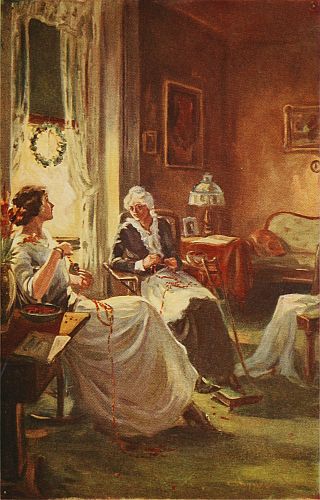

| So by the window the Lady Ariel and Aunt Cheerful gaily made crimson chains for a Christmas tree | 64 |

| Jean drew forth the pitiful little canvas bag and stuffed it full of greenbacks | 112 |

A ruined mill with dripping eaves, a grinding shudder of brakes, and the train halted. With quick interest in her eyes, the traveler alighted, but outside on the sodden village platform her interest fled panic-stricken in an overpowering surge of loneliness and dismay. Surely, surely, thought Jean Varian, a bleak enough goal for her odd caprice! Great, wind-beaten trees dripped above the village and the covered bridge; fog-ridden hills towered in the distance like ghostly gables of the valley; and at the head of[15] the street in the old-fashioned hotel to which days before she had whimsically written for rooms, only a single unpromising light flickered dully through the wind and rain.

But the night was settling rapidly and with a careless direction to the staring baggageman, Jean Varian turned away into the muddy street and made her way to the hotel where a man in boots with a bucket in his hand was stumping heavily away from the pump to the long, low hitching sheds beyond.

It was essentially rural in its homely comfort, the Westowe House, with brightly colored cornucopias in the parlor carpet and hair-cloth parlor furniture blotched with tidies that tobogganed[16] dizzily to the floor at a touch; but Mrs. Pryce, the proprietor's wife, was stout and ruddy and so frankly and intimately curious that Jean kept to her room for the greater part of the day that followed.

The rain continued. Outside, the stable-man tramped noisily about among the steaming horses, the pump creaked under frequent duress; Mrs. Pryce was insistently hospitable and insistently curious; and at twilight, appalled by the dreary monotony of it all, Jean restlessly set forth to explore the village. It was already dark when in her careless circuit she approached the railroad. The night train was puffing leisurely past the sheep-pen and a man was tramping toward the post-office with a mail-bag[17] over his shoulder. Ahead with a promise of further monotony and curiosity flickered the lights of the Westowe House. Jean's footsteps lagged.

Now just behind the station, parallel with the glistening rails, lay a country lane, and down this, in the heart of the rain and dark, twinkled a single light so cheerful and inviting that Jean halted unconsciously. Vaguely she remembered having caught its elfin glimmer the night before, but now as she watched, it twinkled so irresistibly with an inferential atmosphere of warmth and cheer that the girl gathered her wet cloak about her and set off toward it in a pleasant glow of curiosity.

A smell of wet pine filled the lane, but[18] though the way was very dark and a little lonely, Jean Varian hurried on, halting at last with a smothered sigh of envy. For here in the heart of the dripping pine-trees, lay a tiny cottage, so white and trim and cheery that even the croon of the gallant pines that brushed the roof bore in it nothing of the night's melancholy. Now the light that twinkled among the pine-needles and the rain-glisten of the night came from a lamp held through an open porch-window from within by the hand of a tiny woman with a shawl about her head, and even as Jean stared wonderingly, the watcher in the window spoke.

"Good evening!" she called brightly. "It is so very windy and wet to-night.[19] Perhaps I can persuade you to step in and have a cup of hot tea with me!"

"But—but," stammered Jean from the rain and shadows, "I—I did not dream you could see me!"

"Why, neither I can, my dear!" briskly replied the little woman, "but many a cold and weary straggler from the night train sees my light and whenever I call there is, as a rule, an answer! And now,"—with an energetic cordiality wonderfully compelling—"if you will please come straight up the walk and open the front door, you'll find a fire and a welcome just as warm. Why, bless your tired heart," she added with a quick, birdlike turn of her muffled head that brought the light upon her face,[20] "my kettle is singing away here like a cricket. Do hurry!"

Wonderingly, Jean obeyed. Who could withstand the irresistible warmth of the little woman's hospitality? And with the opening of the cottage door, the astonished guest left all the chill and melancholy of the winter night behind her, for here in a snugly-curtained room roared a rollicking, jovial blade of a wood-fire, waggishly throwing the reflection of his ever-busy fire-sword upon the old-fashioned walls and checkerboard carpet, the oval portraits and the snowy supper cloth, trimly decked in china blue, all the while filling the room with his boisterous crackles and chuckles of delight! And steaming madly away[21] in spirited rivalry over an alcohol blaze, a handsome brass kettle, ludicrously fat and complacent, hummed a throaty jubilate of self-approval. Surely the splendid emperor of all kettles! thought Jean Varian, smiling, this exuberant egotist with his polished armor and his plume of steam!

"And such a vain fellow, too, my dear!" chirped an amused voice at Jean's elbow, "but then he's such a very cheerful comrade I forgive him that!" and the girl starting, found herself smiling warmly down into the face of her hostess.

And what a tiny hostess she was to be sure, quite as trim and picturesque in her white woolen gown as the cottage itself. Snow-white, too, her hair, framing a fine[22] old face with eyes of china blue, eyes so bright and friendly that Jean unconsciously likened them to the light among the pines. And like the odor of pine about the cottage, an aura of cheeriness hovered about the owner.

Now presently, as the hospitable little woman went bustling about, intent upon the comfort of her unknown guest in the chair by the fire, Jean saw with a sudden husk in her throat that this cheerful little hostess of hers was very lame; that wherever she went a tiny crutch, half-hidden beneath a fold of her gown, went tap! tap! tapping! steadily along, as sprightly and energetic a crutch as one might find, and somehow the bitterness in the traveler's eyes softened at the[23] sight of it and her beautiful face warmed into kindliness.

"Do please let me help you!" she begged suddenly. And so these two women, brought together by the whim of the one and the kindliness of the other and perhaps by a floating strand of Fate, worked busily together over the making of the tea, the one with the unaccustomed hands of the aristocrat; the other with the deft experience of cheerful self-dependence.

Tap! tap! tap! went the crutch about the room; drip! drip! drip! the rain among the pines; the steaming Emperor hummed and the fire chuckled and in the midst of it all, the hostess suddenly halted.

"Now, my dear," she exclaimed, with swift color in her wrinkled cheeks, "the very foolish folk of Westowe call me Aunt Cheerful and I'd like to have you do the same, for although it's a very foolish name indeed, still I'm only a very foolish old woman and I'm very fond of it."

Aunt Cheerful! Jean glanced at the slight figure leaning lightly upon her crutch with a sudden mist across her eyes.

"Aunt Cheerful it shall be indeed!" she said gently.

"And my lane here they call Pine Tree Lane, because at either end you may catch the pleasant odor of my pines. And the cottage—well, what else could[25] it be, my dear, but Pine Tree Cottage!"

With a sudden impulse Aunt Cheerful crossed the room with a quick tap! tap! of her crutch and laid a small hand impulsively upon Jean's arm.

"My dear," she said wistfully, "you'll pardon a lonely old woman her frankness? I've taken a very great fancy to you! Why not stay to supper with me?"

"Oh, no, no!" protested Jean quickly; "I—you are too kind!" She glanced at the little supper table set for three and Aunt Cheerful smiled.

"Only a foolish fancy!" she nodded. "In reality, my dear, I live alone, quite alone!"

And later, her protests engulfed in the hubbub of calming the indignant Emperor sputtering fussily over this unprecedented neglect, Jean came to learn more fully of this "foolish fancy." Quietly Aunt Cheerful added a fourth place at the table and with ready tact Jean slipped into it unquestioning.

"My dear," exclaimed Aunt Cheerful quickly, "I thank you!" then, catching the warm friendliness and sympathy in the eyes of her guest, she colored.

"Oh, my dear," she burst forth, "never, never was there such a foolish old woman as I. I'm sure you will not laugh at me if I tell you that the plate just opposite is always set for my busy son in the far West. And lonely nights[27] like this when the rain drips through the pines or the snow polka-dots the lane and the ghostly wind comes rattling my windows, I like to pretend that he's there in his chair, big and gallant and handsome as always, and then I—I sometimes talk aloud to him and pass him the dishes I know he likes. Just a foolish mother's game," she added, flushing hotly, "and I—I do not know why it is I have told you my weakness. Surely," with quick apology, "you must think me very silly indeed!"

"Oh, no, no, no!" cried Jean, an odd catch in her voice, "I think it is all very beautiful!" and Aunt Cheerful's face grew radiant.

"Do you indeed!" she exclaimed,[28] beaming. "Well, now, I am pleased. I've always feared it was very weak and silly!" Then, suddenly struck by the rich color in her guest's cheeks and the wonderful gentleness that had magically obscured the shadows in the girl's fine eyes, she added delightedly, "Why, how refreshed you are looking, child! Dear me, I do believe I'll keep you over night. No, not a word, my dear! Just hear the rain and the wind. Why bless your heart, that's answer enough!"

"And now," exclaimed Aunt Cheerful from her chair by the fire, "is the time, my dear, when I always see my Lady of[32] the Fireglow in her flame-colored satin! Jewels of fire flash about her throat and hair, and very beautiful she is too, I fancy, though to be sure I am never able to catch a glimpse of her face!" Aunt Cheerful smiled across the firelit hearth at the shadowy figure of her guest. "And the third place at the table," she owned wistfully, "is always for her, for somehow to me she is the fire's promise of the kind and beautiful wife who may one day come into my big son's life and therefore into mine!"

The clock above the mantel struck nine and to Jean's astonishment a window beside the screen was suddenly raised from the porch side and a boy's head and shoulders appeared, plainly[33] visible in the fan of light from the hidden lamp. Not a very large boy—surely a scant dozen years lay behind him!—but a strangely self-possessed little chap nevertheless, with damp, waving hair, a grim little chin, and cheeks as rosy as the apple of health itself.

Now as Jean watched from her shadowy corner, the boy carefully shifted his oil-skin packet of papers, seated himself upon the window sill and doffed his dripping cap with the air of a court gallant. And mortal ears never heard a stranger conversation.

"Good evening, Lady Cheerful!" he said deferentially, his grave brown eyes seeking the spot by the fire where Aunt[34] Cheerful's white woolen gown glimmered faintly in the firelight.

"Why, good evening, Lord Chesterfield!" returned Aunt Cheerful, a wonderful warmth and affection in her voice; "I trust I see you well this evening, sir?"

"Very well indeed, I thank you, ma'am! I trust," he added very politely, "that your Ladyship is enjoying good health?"

"I am indeed. May I venture to ask your Lordship how you have found business this evening?"

Lord Chesterfield looked gravely at the dripping oilskin.

"The night is very wet," he admitted, "and business poor!"

"Dear, dear! What a pity!"

"But, as usual, I have given myself the honor of stopping at the post-office for your Ladyship's mail."

"Kindly and courteous and thoughtful as ever!" nodded Aunt Cheerful. Lord Chesterfield's cheeks reddened with pleasure.

"There was nothing!" he said regretfully. "Now as to the news"—frowning thoughtfully—"Mrs. Bobbins' twins have the measles."

"Well, now, I am sorry!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful sympathetically.

"And Grandmother Radcliffe's cow 'pears to be growing more mopey and blue each day. She bellows terrible mournful."

"I can't imagine," mused Aunt Cheerful, "what can be the matter with that poor cow!"

"The strange lady at the hotel went walking to-night in the rain and she's not back yet. Most likely she's gone a-visitin'."

"Hum!" said Aunt Cheerful.

"And then"—Lord Chesterfield cleared his throat—"I wouldn't tell you this, ma'am, but your Ladyship would surely ask me. I'm sorry to have to tell you that there's another leak in that roof of mine."

"Another leak! Oh, my dear boy!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful in dismay, startled out of her court manners by her quick solicitude.

"It is nothing, madam, I assure you!" urged Lord Chesterfield gallantly, "I've got mos' a pound of chewin' gum from the boys to mend it with. They took up a chewing gum subscription," he added gratefully.

"Lord Chesterfield," said Aunt Cheerful very soberly, "I'm afraid you'll have to give up that hermit hut of yours. It's growing very leaky! You've thought over very, very carefully that proposition of coming to live with me?"

"Very carefully, ma'am, I thank you!" said Lord Chesterfield firmly. "I'm afraid I prefer to stay a bachelor."

"And may I venture a question concerning the health of your Lordship's many patients?"

"All doing nicely, ma'am, very nicely."

With a quick twist of his arm, the bachelor dropped a newspaper within and rising bowed, a gallant little figure of a gentleman framed in the lamp-glow.

"Allow me to present your Ladyship with one of my papers!" he said courteously.

"And allow me to thank you for it!" interposed Aunt Cheerful gently.

Again the boy raised his tattered cap and smiled, a grave little smile for all its brightness.

"Good night, Lady Cheerful!" he said.

"Good night, Lord Chesterfield and remember—any time your bachelor life grows too lonely—"

But Lord Chesterfield was off into the shadows of the dripping lane, whistling as cheerily as a robin.

Aunt Cheerful turned to the mystified guest at her fireside.

"Oh, my dear," she exclaimed gratefully, "how very tactful of you to make no sound. The presence of a stranger would have confused him so! Just a little game we play each night, Lord Chesterfield and I—"

"What a dear little lad he is!" exclaimed Jean.

Aunt Cheerful bent and turned the dying log.

"A kindly, courteous little gentleman, ever-mindful of my poor lame foot;" she said thoughtfully, "with his proud, boyish[40] heart afire with dreams—dreams of becoming a very great doctor and a gallant gentleman. Why, my dear, his father was such a queer hermit who lived with this little son of his in a ruined shack along the river, a ragged, handsome, silent man of very great culture, 'twas said, and this fall when he died the boy refused to leave his crazy hut. A chore here and a chore there, so he lives, a wee, lovable, busy little hermit, selling his newspapers, sweeping out the school and the church, and doctoring all the sick animals about with arnica and witch-hazel. To be sure a hundred friendly eyes in Westowe watch over him in secret but few dare offer him any aid."

"But why 'Lord Chesterfield'?"

"I have read him such portions of Lord Chesterfield as I deemed suitable," replied Aunt Cheerful, "and we play our little game at his request that he may grow familiar with the ways and words of gentlemen."

And Jean Varian brushed something away from her long dark lashes that sparkled suspiciously like a tear. Surely Aunt Cheerful and gallant Lord Chesterfield were worth the many, many miles of the rainy journey!

"And now, my dear, to bed!" suggested Aunt Cheerful, smiling and with a busy tap! tap! of her crutch she was briskly leading the way up the winding stairway to a room above.

A smell of pine, the lighting of a lamp, the quick crackle of dry wood as Aunt Cheerful bent over a tiny fire-place, and Jean uttered a cry of admiration. Pine cones and branches showered in pattern across the wall-paper and the carpet; pine-sprigged chintz covered the old-fashioned chairs, and from somewhere a pine pillow gave forth the fragrance of the winter forest.

"My Pine Bough Bedroom!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful delightedly; "and how glad I am you like it. And I furnished it so, my dear, in a little wave of superstition. An old and wrinkled gypsy was passing through my lane and when I called her in for a cup of tea, what do you suppose she said?[43] 'Kind lady, great happiness will come to you one day in the heart of the Christmas pines!' Doubtless an idle phrase that came to her with the smell of the pine but I often think of it. Good night, my dear."

But Jean laid an impetuous hand upon the old lady's shoulder.

"Aunt Cheerful," she said gently, "you have not once asked me my name!"

"Why neither I have, my dear," nodded Aunt Cheerful, "but then I fancied you would tell me yourself if you wished me to know."

Jean colored hotly.

"Aunt Cheerful," she said hurriedly, "there are reasons, for a time at least, why—why I can not tell you my name[44] or why I have come to Westowe! Oh, I do hope you will not misunderstand me. May I not," she added pleadingly, "join in name that little group of nobility to which Lord Chesterfield and Lady Cheerful belong?"

"Why to be sure, you may!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful, smiling. "I shall call you the Lady Ariel for you came to me like a beautiful spirit out of the wind and rain. Good night, dear."

Very thoughtfully, Jean loosened the shining masses of her dark hair and brushed it.

"The Lady Ariel!" she mused, smiling. "And surely as whimsical a guest as any spirit of the air might be." Absently the girl's eyes rested upon a book,[45] exquisitely bound in Levant, on a table near-by. It bore the title "Songs of Cheer" and with a smile at the eternal cheeriness of this chance shelter of hers, the girl opened it.

And as the Lady Ariel read, her beautiful face flamed scarlet, and shaking queerly, she dropped to her knees by the snowy bed, all her superb self-possession gone in a passionate fit of weeping.

Brush! brush! went the dripping[46] pines against the window in a ceaseless monody, and presently this very strange guest of Aunt Cheerful's raised her head. Very white and strained her face but her eyes were shining.

Now although Lady Ariel was never quite sure just how it all came about, night found her still at Pine Tree Cottage, and again at dawn she watched Lord Chesterfield at his furtive tasks. And so, eventually, swept away again and again by the warmth of Aunt Cheerful's hospitality, Jean came to linger on at the cottage in the pines, thrilled unaccountably[51] by the unquestioning friendliness of her cheery hostess.

Each night when the mail train came in, Aunt Cheerful's lamp flashed its friendly message through the pines; each night her birdlike voice carried its invitation into the dark of the lane. And sometimes it was a weary villager, homing through the twilight, who answered her call and sometimes an astonished stranger lured into the lane by the smell of the pine and the brightness of her light. But to all the welcome was the same. Aunt Cheerful's cosmic hospitality made no distinctions, and presently Jean came to know that the fame of Pine Tree Cottage was county-wide.

And as regularly as the lamp flashed[52] among the pines, so in mid-evening came Lord Chesterfield with his Lady's mail and her paper, his courteous queries for her Ladyship's health and his relishful exposition of the village news. Brave, kindly little hermit! Jean's heart warmed to his boyish gallantry. And presently when the first constraint had worn away, Lord Chesterfield's courtly queries from the window-sill included the health of the Lady Ariel.

Nights by the fire there was much talk, too, of the beautiful Lady of the Fireglow and Jean grew to marvel at the wealth of love steadily piling up in the heart of Aunt Cheerful for Son Robert's sometime wife. As for "Son Robert" himself, the caress in Aunt Cheerful's[53] voice when she spoke his name, thrilled her guest indescribably. Flying mother-winged about the night's sleepy fireglow, there were eloquent tales of his boyhood daring, of school days when he had won a Harvard scholarship, of his brilliant career in the busy West, but as the days unfolded their glowing flower of biography, Jean found that, manlike, despite his untiring forethought for her comfort, Robert Loring had undervalued what his mother longed for most, his presence! that five thoughtless years had sped busily away since his last home-coming; years so long and lonely for the little cripple in Pine Tree Lane that a quick resentment flamed loyally up in Jean's awakening[54] heart and her eyes softened in a new understanding of the many devices by which Aunt Cheerful Loring had somehow contrived to color the barren years.

"But this Christmas," Aunt Cheerful was wont to finish her eloquent monograph, "he is surely coming for he has written so much about it and oh, my dear!"—with shining eyes—"what a very wonderful Christmas I shall have indeed!"

Thus, imperceptibly, the strange and whimsical comradeship of these two women grew into something stronger, something so deep and beautiful that the Lady Ariel's face grew to mirror its imprint. And Aunt Cheerful, clinging wistfully to the companionship of this[55] lovable, mysterious guest who had come straight into her heart from the wind and rain, deftly lured the Lady Ariel into lingering.

Came the busy fortnight before Christmas, and over the snowy ridges peeped the December sun like the round and jolly face of the Christmas Saint with his snow-beard veiling the hills and the river-valley below. And now with a merry jingle of sleigh-bells Westowe awoke to the activities of the season and Aunt Cheerful's crutch was never so busy tap! tap! tapping about with endless plans for "Son Robert's Christmas." Nights Lord Chesterfield's eyes shone with suppressed excitement as he courteously regaled his noble friends with the[56] village news, and betimes with a wonderful new glow about her heart, the Lady Ariel set out one morning for the busy city to the South upon a tour of Christmas shopping.

There were many errands, and when at night-fall tired and happy, Jean hurried to the station laden with bundles, the mail train was already traveling leisurely up the valley. Wherefore this light-hearted Christmas shopper rode homeward over the country roads in a livery sleigh, cheeks aglow with the winter cold and eyes alive to the still white beauty of the winter night.

It was already supper-time when the sleigh turned into Pine Tree Lane and Jean, entering softly at the rear to surprise[57] Aunt Cheerful, halted noiselessly in the kitchen. For though the room beyond was quite empty save for the humming Emperor and the busy swashbuckler in the fire, Aunt Cheerful was chatting away to an invisible guest. And these were the words Lady Ariel heard:

"A biscuit, Robert?... Certainly. Oh, I am so sorry Lady Ariel missed her train. She has grown so fond of my biscuit.... And here, my dear boy, is your favorite jam.... Robert," she said wistfully, "I do so wish you could grow to love my beautiful Lady Ariel. Each day she grows more lovely. She is so quick and sweet and tireless, so ever-mindful of my comfort and my[58] poor lame foot.... And do you know, Robert, I can not help thinking that with her wonderful gray eyes and the shining masses of her dark hair, she must be very like my Lady in the Fire.... To be sure, Robert, you are right as always.... It is true that I have never seen the face in the fireglow but I would so like that daughter of my dreams to be like my dear, dear Lady Ariel.... No! No! Robert, I do not know who she is.... I will not ask her that.... Surely she will tell me in her own good time if she wishes me to know. And, besides, has she not asked me to trust her?... And Robert, it is so very odd. Though she has the white and beautiful hands of a princess with never a mark of toil upon[59] them, yet she has scrubbed and swept and ironed and baked for me as busily as a farmer's daughter. She is so quick to learn, so gentle and tactful—Oh, Robert!"—her voice shook with a little sob—"I'm altogether a very foolish old woman but I've grown to love her so that I can not let her go out of my life as swiftly and strangely as she came into it. If only you would come and help me keep her—"

But the Lady Ariel was gone, out into the shadows of the pines, the hot tears raining down her face.

And late that night a telegram went singing over the wires to Denver, a telegram having to do with a flame-colored satin and a case of jewels.

"Aunt Cheerful?"

"Yes, Lady Ariel?"

"I've polished the Emperor until he fairly illumines the kitchen!"

"My dear, you pamper him too much!"

"And I've made the salad for supper—"

"Bless your dear, generous heart,[64] child!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful. "You're too good. Now come help me string cranberries for the chapel tree. I'm sure you'll find it restful after such a busy hour in the kitchen."

So by the window the Lady Ariel and Aunt Cheerful gaily made crimson chains for a Christmas tree until the purple of the twilight gathered among the pines and the swaggerer in the fire awoke to fight the gathering shadows with his busy sword of flame. By the window Jean stared absently out at the fading pines.

"Aunt Cheerful?"

"Yes, Lady Ariel."

"How wonderfully tranquil it all is here. See, it is beginning to snow.[65] White and drifting feathers of peace, I'm sure! Oh, Aunt Cheerful," she said with a little sigh, "how much I envy you!"

"Envy me, Lady Ariel?"

"Yes. Your cottage and your pines and the quiet of this dear old lane. Somehow I have grown to love it all! And then all your friends here in Westowe."

"But surely, child, you too have friends!"

"Not so sincere and loyal as yours, Aunt Cheerful. And then you have Lord Chesterfield and your—your son in the West and I have no one."

"No one!"

"No one!" Jean repeated. "Never a[66] kinsman even, save a nomadic uncle with a strain of gipsy blood in his veins and even he faded out of my life like all the others years ago. It—it is a very odd thing, Aunt Cheerful, to be quite alone, and sometimes it is very, very lonely."

"Oh, my dear Lady Ariel!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful in real distress. "I am so sorry!" For an impetuous instant a question seemed to hover upon her lips, then with a quick movement of decision she was tap-tapping about the room, lighting the lamp and drawing the shades.

"Come, come, Lady Ariel!" she exclaimed, smiling. "You're not in your usual good spirits to-night! We'll set[67] the Emperor to singing and have our tea!"

But Jean's depression lingered and so it was that when Lord Chesterfield peered into her shadowy corner by the fire that night, her chair was empty.

"Good evening, Lady Cheerful!" he said, disappointment in his voice.

"Why, good evening, Lord Chesterfield. Dear, dear! your Lordship's cap is full of snow!"

"It is nothing, madam, I assure you! I trust your Ladyship is well?"

"Very well indeed."

"And the Lady Ariel?"

"Well"—Aunt Cheerful hesitated—"a little quiet and tired, I should say. She has gone up to bed."

Into Lord Chesterfield's eyes leaped a sudden excitement.

"A 'normous box came by express," he burst forth breathlessly, "and it was full up of spensive, glittery Christmas things for the chapel tree and—and—a letter came from a candy man and he said a strange lady'd bought and paid for s'ficient candy and oranges and—and everything for mos' everybody in Westowe to be delivered at the Sunday School day before Christmas and—and presents came on ahead in a box 'cause they won't spoil waitin' and—and nobody knows—"

"Oh, my dear Lord Chesterfield," broke in Aunt Cheerful in alarm, "do, do, my dear boy, take a breath!"

"Who sent 'em!" finished Lord Chesterfield. "And Grandmother Radcliffe she reckons maybe Lady Ariel is a princess in disguise and she sent 'em."

"A princess in disguise!" exclaimed Aunt Cheerful. "Dear, dear, that would be strange!"

"And maybe," went on Lord Chesterfield in growing excitement, "maybe your Ladyship will rec'lect how my dog medicines were gettin' pretty low and owin' to er—to—er—" His Lordship cleared his throat with a prodigious "Hum!—I beg your Ladyship's pardon but—er—were financial embarrassments just the words you told me that time?"

"Financial embarrassment!" nodded Aunt Cheerful gravely.

"Owing to my financial embarrassments I couldn't buy more till after Christmas and—and this morning, ma'am, there was an express package for me with witch-hazel and arnica and sponges and liniments and bandages and mos' a reg'lar doctor's outfit in it. Mos' likely I'll 'speriment on Carlo's rheumatism to-night with a new liniment."

"Now I do wonder," mused Aunt Cheerful absently, "if your mysterious friend could possibly be the one who keeps my garden so trim and chops my kindlings. Dear, dear! What a very strange and mysterious place Westowe has become!"

Lord Chesterfield's fine little face colored hotly.

"I hardly think they are the same," he owned honestly; then, quick contrition in his eyes, he vaulted lightly over the window sill and drew a letter from his pocket. "Oh, Lady Cheerful," he apologized, "I do beg your Ladyship's pardon. Fact is, I—I mos' forgot your letter!"

"Why, bless your heart, child," exclaimed Aunt Cheerful warmly, "who wouldn't forget a letter with such a magic box on his mind! Your Lordship will pardon me if I read it this very minute? It's from my son!" And Lord Chesterfield bowed a courtly acquiescence.

So with swift color in her cheeks, Aunt Cheerful read, but as she read her hand[72] began to tremble and suddenly the letter fluttered unheeded to the floor and a great tear rolled slowly down her face and splashed on the white woolen gown. And even as he watched, his grave little face perturbed, the mantle of formal courtesy vanished and Lord Chesterfield sprang forward, a kindly little lad alive with sympathy.

"Oh, Aunt Cheerful," he blurted boyishly, "I'm awfully sorry!"

But with a muffled sob Aunt Cheerful patted his arm, taking refuge in the words of the game they played.

"It—it is nothing at all, Lord Chesterfield, I assure you!" she said bravely.

"My busy son writes me that—that after all he can not come for Christmas."

But even as she bent to regain the letter, she began trembling and crying again so pitifully that Lord Chesterfield's face colored darkly and for all he bit his lips like the brave little fighter he was at all times, still a great sob welled up in his own throat and his eyes grew gentle. And presently in the quiet, Aunt Cheerful felt the diffident touch of a boyish hand upon her shoulder and looking up met the eyes of the little hermit, oddly resolute for all their sympathy.

"Aunt Cheerful," said he firmly, "I—I'm 'fraid I'd better stay here all night. Fact is," with a squaring of chin and shoulders, "I feel that you'd better have a man in the house."

But Aunt Cheerful's wan smile bore in it something resolute of her old cheeriness.

"Oh, my dear boy," she exclaimed gratefully, "it is more than good of you to offer, but you must remember poor Carlo's rheumatism and the new liniment and all the responsibilities of your bachelor life. And anyway I'm quite alright now. Silly old women have such spells."

So presently, after a deal of urging, Lord Chesterfield departed and Aunt Cheerful went tap! tap! tapping softly out into the kitchen to mix her bread. And even as she worked, a perturbed little sentinel with a round boyish face peered furtively in at the kitchen window,[75] loath to leave the cottage among the pines when sorrow lay upon it.

Now as Aunt Cheerful worked she began to sing, and the song was one that had often bolstered her waning courage before. And surely in the very words of it lay the fragrance of her own resourceful cheeriness.

In the single room of his shanty Lord Chesterfield lit his lamp, and truly light never fell upon a stranger boyhood shelter. For the hermit's rude bed was[80] neatly made and the floor as neatly swept, his battered cookstove polished and the medicine bottles upon his rickety table ranged in a careful row. And once the busy hermit had raked his fire into a bright and warming glow, for all its lonely rattling when the wind blew, the river shanty was as snug and neat a place as one might find.

Now as Lord Chesterfield bustled energetically about the fire, there came a whining and a scratching at the shanty door and, as he opened it, a huge dog limped slowly in with a joyous bark of greeting. With ready affection in his eyes, the hermit bent and patted the shaggy brown head of his visitor, for this was Carlo, the toll-gate keeper's old[81] and rheumatic pensioner, who nightly limped up the tow-path to be properly bathed and petted. And the dialogue of the gallant Doctor and his patient-in-chief barely varied.

"Good evening, Carlo!" (very brisk and professional).

A joyous bark.

"And how is the rheumatism to-night?"

A very great wagging of a very bushy tail but a bark of considerable uncertainty.

"Hum! Well, well, we'll have to attend to that. Step right over this way if you please!" And the Doctor, frowning portentously, bathed Carlo's flank ever so gently, with now and then a[82] kindly word of reassurance. These medical attentions properly completed, Carlo, whose sense of professional etiquette was none too keen, fell to nosing frankly about the hut until he found a certain plate of scraps, and having neatly attended to this single spot of disorder, he limped back to the hermit and suggestively lowered his handsome head. Whereupon the Doctor removed a very small package tied to his collar and grandly bowed his patient to the door.

A blast of wind rattled the shanty as Carlo departed. On tiptoe the hermit locked the door, carefully drew the shades, and with infinite caution removed a plank from the floor. Very furtively he drew forth a dirty canvas[83] bag, pitifully small for all its pleasant clink and unwrapped Carlo's package, a coin which Carlo's kindly master nightly sent for Carlo's fee. Then together with such coins as he could spare from the day's proceeds this provident little hermit hid them all away again in the canvas bag beneath the plank, for this was the hidden hoard that Lord Chesterfield fancied would one day make him a very great doctor.

And as the final task of the busy evening, the hermit wrote a letter.

"December 18th.

"Dear Mr. Robert Loring:"She got your letter and cried and she most alwus never cries so shaky, Aunt[84] Cheerful Loring I mean. Oh, please do come! She feels so awful bad and once when I was awful sick this winter she lived three days in this old shanty here with me and sat up all night account of medacines and no other bed and she read me every day bout Lord Chesterfield and I'd like to do something big for her she's so awful brave and so awful lame. Sometimes like to-night when I looked in the winda she sings to keep her spirits up. Oh, please, please Mr. Loring, can't we maybe surprise her for Christmas? I do most everything I can for her but just one thing you could do would be more than all. Five years is awful long. Most likely you won't know who I am unless she wrote. She calls me[85] Lord Chesterfield and lots of folks here call me Doc and the hermut but, sir, I have the honer to sine myself—

"Norman Varian."

For so Lord Chesterfield fancied his illustrious namesake might finish such a letter.

And as he sealed the letter, the boy looked wistfully up at a ragged photograph of his dead father tacked carefully above the table and very slowly he read aloud the single line of writing beneath it.

"Always remember, little son," it read, "that first of all, though you've seen hard times, you're a gentleman!"

And suddenly Lord Chesterfield's[86] brave little head went forward upon his hands with a choking sob, for after all he was only a proud and lonely little bachelor who had greatly loved his father.

So the little hermit's letter went forth upon a Christmas mission to come to its final goal in a luxurious suite of offices in Denver on the desk of Robert Loring. And Robert Loring read the eloquent plea with unwonted color in his face and a startled shame in his fine eyes, for, unconsciously vivid, the boy's letter had strikingly bared the inner life of his brave and cheerful mother.

"Five years!" said Robert Loring aghast. "It can't be!"

But swiftly reviewing the years[87] crowded with activity he knew that the little hermit had written the truth, and he flushed again. For the thought of his mother's lonely life in Pine Tree Lane subtly dwarfed the urgent calls of effort and ambition which had kept him from her. A giant hand of rebuke indeed that Lord Chesterfield had wielded.

So, swiftly over the night wires went a telegram to one Norman Varian, and even as Robert Loring wrote the lad's name, he stared at it very thoughtfully.

And up through the snow-sparkle of the steep moon-lit path to the chapel on the hill climbed Aunt Cheerful Loring, helped ever so gently upward by the sturdy arm of gallant Lord Chesterfield. Snow-sparkle and a Christmas moon and[92] the sound of the chapel organ through the lighted windows above! What wonder that all of it lured Aunt Cheerful to climb as she had never climbed before, with scarcely a thought for the poor lame foot.

"Not so fast, Lady Cheerful!" begged the boy gently.

"But, my dear Lord Chesterfield," urged Aunt Cheerful with a brisk tap! tap! of her crutch, "I can not possibly miss any of this wonderful Christmas celebration for which you have worked so busily and—hear! already they are singing the Christmas hymn!"

Down through the cold air from the moonlit chapel above came the sound of a reverent chorus chanting "Holy[93] Night," and Lord Chesterfield's brown eyes glowed strangely.

"It—it is only the song service they have beforehand," he said re-assuringly, "for—for to-night, Aunt Cheerful," he added with smothered excitement, "they can't begin without me!"

Pine and holly and tinsel and gifts, so they loomed ahead as Lord Chesterfield led his honored lady to her pew and bent over her with a flame of color in his smooth, young cheeks.

"Aunt Cheerful," he stammered excitedly, "I—I beg your Ladyship's pardon but—but will you please 'scuse me now. I—I've got a mos' important errand!"

Primly the hermit had climbed the[94] chapel hill with his lady, but now with never a backward look he raced madly down the path and through the village to the railroad station, a flushed and panting youngster trembling with excitement. Far below where rails and moonlit sky merged appeared a light and upon its steadily growing disk Lord Chesterfield fixed his eyes in a fever of fascination. Chug-a-chug! Chug-a-chug! Chug-a-chug! How desperately slow it crept up through the snow-silver of the valley! And how wildly the hermit's glowing heart pounded away beneath his Sunday suit!

On came the train at last and halted, and presently Lord Chesterfield was hurrying excitedly down the platform[95] toward a man, young and tall, whose handsome eyes were surely of a most familiar blue. Gravely the little hermit raised his cap and bowed.

"Good evening!" he ventured sturdily "Are you—are you Mr. Robert Loring?"

"Robert Loring, indeed!" answered the young man gravely; "and very much at your service." And his eyes were gentle as he held out his hand. "And you, I take it, are Lord Chesterfield himself. Well, sir, I'm glad to know you."

Now there was such an earnest ring of respect and deference in this young man's pleasant voice that Lord Chesterfield colored with pleasure. So, very gravely, these two shook hands and, still[96] finely punctilious, the little hermit cleared his throat.

"May I," he queried politely—"may I—er—take you to my—er—bachelor 'partments for something to eat first?"

Robert Loring's keen eyes traveled over the manly figure of his little friend with never a smile.

"Let me thank your Lordship," he said gratefully, "but I've already dined. From now on, sir, my time is yours."

Lord Chesterfield grasped his arm in a spasm of excitement.

"Oh, sir, Mr. Robert," he burst forth in great relief, "I am so awful glad, for there ain't a single minute to lose. Bill Flittergill, sir, he went and bust his arm a while back and oh, sir, will you come[97] to the chapel and take his place and dress up in the Santa Claus suit and—give the presents and—and when I say like this—'Lord Chesterfield's present to Aunt Cheerful Loring with his respects!' will you just—just take off your mask when she comes up and oh—sir, will you?"

And Robert Loring rested one hand very gently on the boy's shoulder.

"Old chap," he said huskily, "I want you to understand that I leave everything, absolutely everything to you. I've managed things long enough and it seems to me I've made a most astonishing mess of it!"

So that night in Westowe Chapel a broad-shouldered Kris Kringle dispensed the Christmas gifts as the hermit[98] directed until the glittering tree was fairly stripped and the magic box quite empty, and at last with a hoarse little quaver in his voice, Lord Chesterfield came to the final name upon his list.

"Lord Chesterfield's present to Aunt Cheerful Loring!" he announced with a gulp, and, coloring with pleasure, Aunt Cheerful came hurrying up the aisle with a brisk tap! tap! of her crutch.

"Now, oh, now, Mr. Robert!" prompted Kris Kringle's agitated helper. So with a hand that visibly shook, Robert Loring removed his beard and mask and stepped from the Christmas shadow of the pine boughs.

For a tense instant Aunt Cheerful stared, stared at the smiling face of her[99] big and gallant son with eyes so wild and startled that she seemed but a pitiful little crippled ghost swaying weakly upon her crutch, then the ever-busy crutch fell unheeded to the floor and Aunt Cheerful Loring fell sobbing to her knees, one trembling out-stretched hand clutching desperately at the ragged fur on Kris Kringle's coat as if to keep the dear apparition from fading away again before her very eyes.

"Oh, Robert, oh, my dear boy!" she cried incoherently. "It—it was the Christmas pines as the gipsy said—" then in the hush that spread electrically over the little chapel, she began to shake and sob and laugh so queerly that Lord Chesterfield leaped to her side. But[100] Robert Loring, with misty eyes, bent and gently raised his mother to her feet.

"Brave, brave little mother!" he said huskily. "I did not know."

Somewhere in the tear-dimmed host of friends within the chapel, a kindly voice in a wave of quick consideration for the tearful little cripple clinging so pitifully to her son, struck up the Christmas hymn and once more, that eventful Christmas Eve, the strains of "Holy Night" went sweeping out from the hill chapel over the moonlit snow.

"My maid, Celeste, has forwarded to me your letter," she wrote, "and now when I know that I must write you where I am and why I have come here, that at last I must answer your insistent question, oh, Robert!—it is very hard indeed.

"How mockingly to-night your words are ringing in my ears!

"'And so,' you said that memorable night, 'it is but right for me to tell you now, Jean, that with marriage, if you[104] grant me that happiness, my brave and lonely little mother comes back into my home-life for all time!'

"Very handsome and very resolute you looked, but Robert, I wonder if you guessed what a queer resentful chill crept into my selfish heart at your words. Like a grim leper stalking at my side rose the thought that once more Life was ironically robbing me of its finest and sweetest. Oh, Robert, how can I write you now that I did not want your mother in my home and life, intruding upon the first happiness of my lonely life—that I wanted only you!

"I asked you to wait without seeing me again until I should write you and with Celeste's connivance I slipped away[105] in the night, bent upon the maddest, crudest whim that ever selfish heart devised. For I came to the little village you had so often described—to Westowe—and I came—yes, I must write it all crude and narrow as it is—to appraise, to coldly analyze and dissect—your mother, to see if I deemed her worthy a place in my home and my new life with you! And out of the rain and dark, Fate's twinkling light lured me to her very door!

"For, Robert, I am here in the dear peace and quiet of this pine-scented lane, unknown, unquestioned, trusted as I surely do not deserve, lingering on day by day with this dear, brave little mother of yours, and now I know that it[106] is I who am not worthy, that my very quest was a profanation that makes my cheeks burn with the utter shame of it. And something has stirred in my lonely heart at the sight of her that has been hushed since early childhood. So often these days I find myself repeating those wonderful words of Lowell's:

"So the leper of selfish resentment no longer crouches at my side. Instead there is something so shining and beautiful that I grow afraid. 'In many climes without avail!' And even that is I, Egypt and India and Syria and the uttermost parts of the world, so in a mad search for life I have gone and gone again and here in the heart of the pines I have found life and peace and love, the Holy Grail.

"After all, Robert, how much of life's heart-glow I have been denied until now. Those black and bitter childhood days, the under-current of resentment because the only heir to the Varian millions was[108] not a boy, the tearless agony of the nights when first divorce and later death took my father and mother out of my life and I cried for sisters, for brothers, for cousins, for anything in God's world to give some touch of humanness to my barren life—such is my cycle of memory. I wonder if you can guess the utter desolation that comes with the knowledge that you are quite alone with never a single blood-tie to warm the ice about your heart.

"But, now, I have worked with my hands. I have scrubbed and ironed and baked, I have lived for another besides myself, I have watched the lives of two whose brave and cheerful compassion for each other bears in it the touch of[109] holiness and I have come to know a wee soldier whose sturdiness on life's firing line, like that of your mother, has shamed me again and again. Such a wonderfully courteous little lad he is, Robert, with his hermit hut and his buried savings and his dreams of becoming a very great doctor. And some day when I can devise a way of breaking through the wall of his pride, I am going to make him what he dreams. Robert, I think the ice is melting around my heart at last. I am gaining a broader vision.

"Lady Ariel—it is so Aunt Cheerful calls me. Oh, Robert, how can I go to her and tell her why I came, how I linger here day by day hoping for courage to[110] ask her pardon. And it has grown even harder now that I know that she would have the kind and beautiful wife of her son like Lady Ariel, that she has whimsically chosen to see in me her fanciful Lady of the Fireglow garbed wondrously in flame-colored satin! For how can I let her glimpse the cruel canker that lay in the heart of the daughter of her dreams. On the bed as I write lies a gown of 'flame-colored satin' and the Varian jewels, and this moonlit Christmas Eve when she comes from the chapel, I shall go to her as she has dreamed of me and on my knees I shall beg her forgiveness and a place in the beautiful shrine of her brave and cheerful heart.

"Oh, Robert, pray for me that I may not hurt her!"

Very thoughtfully Jean sealed the letter and directed it to Robert Loring, then she began a brisk pilgrimage about the quiet house. Holly and mistletoe and Christmas wreaths came mysteriously to light from a box beneath the Lady Ariel's bed, and soon the cottage among the pines smiled cheerfully through a Christmas flare of pine and holly. For Aunt Cheerful's Christmas interest had somehow waned after Robert's letter, and at the hermit's diffident suggestion, Lady Ariel had taken the pleasant task upon herself.

And when the deft and busy decorator had finished her work, she slipped into[112] her cloak and went hurrying through the village toward the covered bridge. Very lonely and small the hermit's hut in the moonlight and with a catch in her throat, Jean took the rusty key from the nail and entered. Only Aunt Cheerful and Lady Ariel knew the secret of the buried savings. So to-night Jean hurriedly searched the hermit's floor for a certain creaking board, and when at last she drew forth the pitiful little canvas bag, she stuffed it full of greenbacks.

The chill silver of the winter moonlight flooded brightly through the open door, haloing the figure of the girl upon her knees in the desolate shanty and flashing full upon the ragged photograph above the table. So as Jean[113] turned, her startled eyes rested directly upon the features of the hermit's father, and the girl stared aghast, her face white in the moonlight. For the face was the face of her nomad Uncle whose life had been irrevocably marred by the cruelty of her father. And as Jean stared, somewhere within her the ice melted for all time. Starved and eager strands of kinsmanship went flying out to twine hungrily about the gallant heart of Lord Chesterfield, and there upon her knees in the river shack, the heiress to the Varian millions fell to sobbing and praying incoherently for the love of her little cousin. And even as she prayed, faintly over the village came the echo of the Christmas hymn.

"I beg your pardon," said Robert Loring, "but my mother bade me tell the Lady Ariel that she has gone with Hiram Scudder to carry the chapel's Christmas gifts to the poor of Westowe."

But oddly enough there was no answer at all from the white-aproned worker in his mother's kitchen, moreover she did not even turn her head and a little puzzled, Robert Loring raised his voice.

"I beg your pardon," he began again and halted—for Lady Ariel had turned as he spoke with a wistful smile of apology about her lips.

Unutterable astonishment flamed up in Robert Loring's eyes, but he did not speak, for there was something in Jean's face that somehow made the power of words depart. In a queer silence they faced each other, Robert Loring's memory flashing back to the night at the opera when he had first seen this girl before him in the white and silver of trailing[119] satin, when the beautiful chill and bitterness of her eyes had left their imprint upon his soul for eternity. There were no shadows in her eyes to-night; and smoothing away the lines of soul-rebellion, a new strength and sweetness lay wistfully about her mouth. Ruffled hair and toil-marked hands! With a sudden bound, Robert Loring caught the girl's hands within his own.

"Oh, Jean, Jean!" he cried wonderingly, "what does it all mean? Celeste would not tell me where you had gone." But Jean slipped from his arms with a laugh that was half a sob.

"Oh, no! no! Robert," she said bravely, "you must read your letter first and know me for what I am."

So by the kitchen window, Robert Loring read his letter and when he finished his eyes were very thoughtful.

"Jean, dear," he said gently, "there is much for which you and I must one day beg my little mother's pardon but surely you have not erred so much as I."

By the fireglow with the Emperor humming a festive prediction of tea for the Christmas supper, Robert Loring heard the story of Lady Ariel's whimsical journey and its climax in the hermit's hut, but when the jingle of sleigh-bells outside announced the halting of Hiram Scudder's sleigh Jean went flying happily from the room and up the stairs. With a tap! tap! tapping! of the crutch—never so brisk and cheerful as[121] to-night, Aunt Cheerful presently entered upon the arm of the gallant hermit.

"Oh, Robert, my dear boy!" she exclaimed happily. "How very like my dear Lady Ariel to surprise me with all this glow of holly and the Christmas wreaths. You can not imagine how cheerily they smiled at me through the pines! And dear me, bless the child's heart, the table is set for a little supper and the Emperor singing a Christmas hymn. Never, never was there such another Christmas since the world began."

But Robert Loring drew his mother to a seat by the fire and gently began to tell her something of the wife who was to come at last into his mother's life and[122] his own, and somehow as he talked Aunt Cheerful grew very quiet and a little sad and presently she turned quite around that she might not look into the fireglow for since Lady Ariel's coming she had made wistful plans of her own about Son Robert's wife and the fireglow mocked her with the impotency of them all. And when a quick step on the stairway betokened the return of Lady Ariel, a great tear rolled slowly down Aunt Cheerful's face and turning she fell back in her chair with a cry of awe.

For surely so radiant a Christmas vision never stood framed in a holly-crowned doorway before. Flame-colored satin trailed about the Lady Ariel's slender figure; diamonds flashed about[123] her throat and hair. And as she gasped and stared, first at the eloquent eyes of her son and then at the Christmas vision in the doorway, Aunt Cheerful Loring knew the truth. With a wild tapping of her crutch she went flying swiftly across the quiet room.

"Oh, my beautiful Lady of the Fireglow!" she cried, sobbing for the very joy of it all. "My dear, dear Lady Ariel!"

And Lord Chesterfield, kindly little courtier that he was, began briskly to poke the fire that he might not be an outside witness to this Christmas scene of joy and reunion, but a great loneliness swept over him and all the while he was stirring up the sleepy swashbuckler[124] in the fire he was swallowing manfully. So in his tearful abstraction the hermit did not know that Jean's eyes were full upon him or that with a soft rustle of the flame-colored satin she had crossed the room and seated herself beside him.

"Lord Chesterfield," said Jean gently, "all these wonderful days you have not once told me your Lordship's name."

"Why, why, no, Lady Ariel," stammered the boy in quick apology, "I haven't. I do beg your Ladyship's pardon. It is Norman Varian."

"Norman Varian!" repeated Jean. "It is a very familiar name, your Lordship."

Smiling Lady Ariel slipped a paper into the hermit's hand. And these were[125] the very astonishing words the paper bore:

"I hereby pledge myself by the memory of my dead uncle, Norman Varian, to make of my brave little cousin a gentleman and a scholar and a very great Doctor.

"Christmas eve. Jean Varian."

And when Lord Chesterfield reached the familiar surname at the end, he knew why Lady Ariel's beautiful face had haunted his dreams—it was a face very like the face of his dead father; moreover he knew why the look in the girl's gray eyes had so hurt his throat for, unlike his own, they were Varian eyes. And as the brave little hermit slowly came to realize that in this lonely world[126] he was not quite alone, that here were kindly eyes that had the right of kinsmanship to watch over his sturdy climb to manhood, his pride and independence ruthlessly deserted him and he dropped on his knees and buried his face in Jean's lap, a forlorn little lad unnerved at the end of a gallant fight.

"Oh, Cousin Jean," he blurted with a great sob, "I been so awful lonely 'specially when the wind blew nights and I missed daddy so and—and the canvas bag's been fillin' so awful slow and mos' every rain there was a new leak—"

Jean stroked her cousin's hair with a hand that trembled a little.

Now in the silence that fell over the room, the wrathful Emperor burst suddenly[127] into a perfect bubble of ferocity. He steamed and he hissed and he bubbled and grumbled, he fumed at the mouth and rattled his helmet and tossed his plume of steam about in an imperial rage, for when had royalty been so persistently ignored as on this Christmas Eve! And presently as the four sat down to the Christmas supper, through the moonlit pines came the sound of the chapel bell ringing in a Christmas morning.

Transcriber's Note: Varied hyphenation was retained most notably

in that Fire-glow or Fire-Glow retains a hyphen in some titles

but not in the text.

|