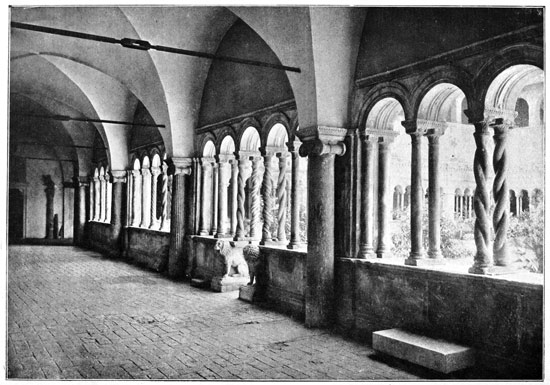

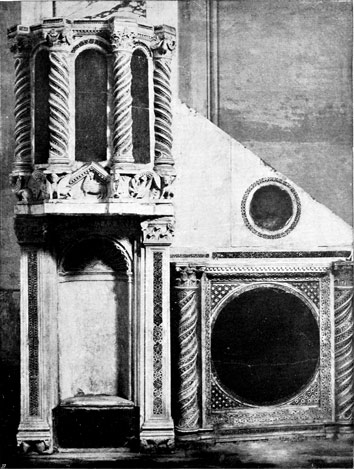

Cloister of S. John Lateran, Rome, 12th century.

(From a photograph by Alinari.)

Frontispiece

See page 66.

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

The anchor for Footnote 11 is missing in the text. Its location has been approximated.

The reference to Hexham church on page 157 is a possible typo.

The comma in the Roman numeral on page 204 is a possible typo.

Schmarzow on pages 230 and 405 should possibly be Schmarsow.

The index entry to Giovanni Buoni da Bissone points to entries for both Buoni and Bono, and Bissone and Bissoni.

Cloister of S. John Lateran, Rome, 12th century.

(From a photograph by Alinari.)

Frontispiece

See page 66.

THE

CATHEDRAL BUILDERS

THE STORY OF A GREAT MASONIC GUILD

BY LEADER SCOTT

Honorary Member of the 'Accademia delle Belle Arti,' Florence

Author of 'The Renaissance of Art in Italy,' 'Handbook of Sculpture,' 'Echoes of Old Florence,' etc.

With Eighty-three Illustrations

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

153-157 Fifth Avenue

1899

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

London & Bungay.

In most histories of Italian art we are conscious of a vast hiatus of several centuries, between the ancient classic art of Rome—which was in its decadence when the Western Empire ceased in the fifth century after Christ—and that early rise of art in the twelfth century which led to the Renaissance.

This hiatus is generally supposed to be a time when Art was utterly dead and buried, its corpse in Byzantine dress lying embalmed in its tomb at Ravenna. But all death is nothing but the germ of new life. Art was not a corpse, it was only a seed, laid in Italian soil to germinate, and it bore several plants before the great reflowering period of the Renaissance.

The seed sown by the Classic schools formed the link between them and the Renaissance, just as the Romance Languages of Provence and Languedoc form the link between the dying out of the classic Latin and the rise of modern languages.

Now where are we to look for this link?

In language we find it just between the Roman and Gallic Empires.

In Art it seems also to be on that borderland—Lombardy—where the Magistri Comacini, a mediæval Guild of Liberi Muratori (Freemasons), kept alive in their traditions the seed of classic art, slowly training it through Romanesque forms up to the Gothic, and hence to the full vi Renaissance. It is a significant coincidence that this obscure link in Art, like the link-languages, is styled by many writers Provençal or Romance style, for the Gothic influence spread in France even before it expanded so gloriously in Germany.

I think if we study these obscure Comacine Masters we shall find that they form a firm, perfect, and consistent link between the old and the new, filling completely that ugly gap in the History of Art. So fully that all the different Italian styles, whose names are legion—being Lombard-Byzantine at Ravenna and Venice, Romanesque at Pisa and Lucca, Lombard-Gothic at Milan, Norman-Saracen in Sicily and the south,—are nothing more than the different developments in differing climates and ages, of the art of one powerful guild of sculptor-builders, who nursed the seed of Roman art on the border-land of the falling Roman Empire, and spread the growth in far-off countries.

We shall see that all that was architecturally good in Italy during the dark centuries between 500 and 1200 A.D. was due to the Comacine Masters, or to their influence. To them can be traced the building of those fine Lombard Basilicas of S. Ambrogio at Milan, Theodolinda's church at Monza, S. Fedele at Como, San Michele at Pavia, and San Vitale at Ravenna; as well as the florid cathedrals of Pisa, Lucca, Milan, Arezzo, Brescia, etc. Their hand was in the grand Basilicas of S. Agnese, S. Lorenzo, S. Clemente, and others in Rome, and in the wondrous cloisters and aisles of Monreale and Palermo.

Through them architecture and sculpture were carried into foreign lands, France, Spain, Germany, and England, and there developed into new and varied styles according to the exigencies of the climate, and the tone of the people. The flat roofs, horizontal architraves, and low arches of the Romanesque, which suited a warm climate, gradually changed as they went northward into the pointed arches vii and sharp gables of the Gothic; the steep sloping lines being a necessity in a land where snow and rain were frequent.

But however the architecture developed in after times, it was the Comacine Masters who carried the classic germs and planted them in foreign soils; it was the brethren of the Liberi Muratori who, from their head-quarters at Como, were sent by Gregory the Great to England with Saint Augustine, to build churches for his converts; by Gregory II. to Germany with Boniface on a similar mission; and were by Charlemagne taken to France to build his church at Aix-la-Chapelle, the prototype of French Gothic.

How and why such a powerful and influential guild seemed to spring from a little island in Lake Como, and how their world-wide reputation grew, the following scraps of history, borrowed from many an ancient source, will, I hope, explain.

It is strange that Art historians hitherto have made so little of the Comacine Masters. I do not think that Cattaneo mentions them at all. Hope, although divining a universal Masonic Guild, enlarges on all their work as Lombard; Fergusson disposes of them in a single unimportant sentence; and Symonds is not much more diffuse; while Marchese Ricci gives them the credit of the early Lombard work and no more. I was led at length to a closer study of them by the two ponderous tomes on the Maestri Comacini[1] by Professor Merzario, who has got together a huge amount of material from old writers, old deeds, and old stones. But valuable as the material is, Merzario is bewildering in his redundancy, confusing in his arrangement, and not sufficiently clear in his deductions, his viii chief aim being to show how many famous artists came from Lombardy.

I wrote to ask Signor Merzario if I might associate his name with mine in preparing a work for the English public, in which his research would furnish me with so much that is valuable to the history of art, but to my regret I found he had died since the book was written, so I never received his permission; though his publisher was very kind in permitting me to use the book as a chief work of reference. With Merzario I have collated many other recognized authorities on architecture and archæology, besides archivial documents, and old chronicles. I have tried to make some slight chronological arrangement, and some intelligible lists of the names of the Masters at different eras. The researches of the great archivist Milanesi in his Documenti per la Storia dell' Arte Senese, and Cesare Guasti in his lately published collection of documents relating to the building of the Duomo of Florence, have been of immense service in throwing a light on the organization of the Lodges and their government. All that Signor Merzario dimly guessed from the more fragmentary earlier records of Parma, Modena, and Verona, shines out clear and well-defined under the fuller light of these later records, and helps us to read many a dark saying of the older times.

My thanks for much kind assistance in supplying me with facts or authorities, are due to the Rev. Canonico Pietro Tonarelli of Parma cathedral; the Rev. Vincenzo Rossi, Priore of Settignano; Commendatore John Temple Leader of Florence; and to my brother, the Rev. William Miles Barnes, Rector of Monkton, who has written the "English link" for me. Acknowledgments are also due to Signor Alinari and Signor Brogi of Florence, and to Signor Ongania of Venice, for permitting the use of their photographs as illustrations. ix

| PAGE | ||

| PROEM | v | |

| BOOK I ROMANO-LOMBARD ARCHITECTS |

||

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | THE GUILD OF THE COMACINE MASTERS | 3 |

| II. | THE COMACINES UNDER THE LONGOBARDS | 31 |

| III. | CIVIL ARCHITECTURE UNDER THE LONGOBARDS | 60 |

| IV. | COMACINE ORNAMENTATION IN THE LOMBARD ERA | 71 |

| V. | COMACINES UNDER CHARLEMAGNE | 90 |

| VI. | IN THE TROUBLOUS TIMES | 108 |

| BOOK II FIRST FOREIGN EMIGRATIONS OF THE COMACINES |

||

| I. | THE NORMAN LINK | 121 |

| II. | THE GERMAN LINK | 133 |

| III. | THE ORIGIN OF SAXON ARCHITECTURE (A SUGGESTION), BY THE REV. W. MILES BARNES | 139 |

| IV. | THE TOWERS AND CROSSES OF IRELAND | 161 |

| BOOK III ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTS |

||

| I. | TRANSITION PERIOD | 171 |

| II. | THE MODENA-FERRARA LINK | 192 |

| III. | THE TUSCAN LINK. | |

| 1. PISA | 206 | |

| 2. LUCCA AND PISTOJA | 225 | |

| IV. | ROMANESQUE AND GOTHIC ORNAMENTATION | 242 |

| V. | CIVIL ARCHITECTURE OF THE ROMANESQUE ERA | 256 x |

| BOOK IV ITALIAN-GOTHIC, AND RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTS |

||

| I. | THE SECESSION OF THE PAINTERS | 265 |

| II. | THE SIENA AND ORVIETO LODGES | 282 |

| III. | THE FLORENTINE LODGE | 308 |

| IV. | THE MILAN LODGE | 345 |

| 1. THE COMACINES UNDER THE VISCONTI | 349 | |

| 2. THE CERTOSA OF PAVIA | 372 | |

| V. | THE VENETIAN LINK | 383 |

| VI. | THE ROMAN LODGE | 400 |

| EPILOGUE | 423 | |

| AUTHORITIES CONSULTED | 427 | |

| INDEX | 429 | |

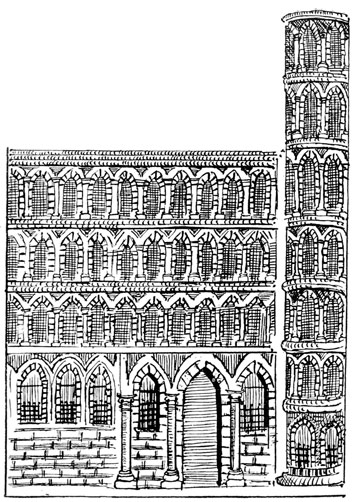

| Cloister of S. John Lateran, Rome | Frontispiece | |

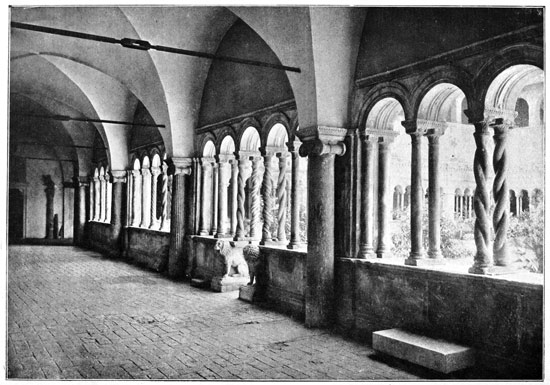

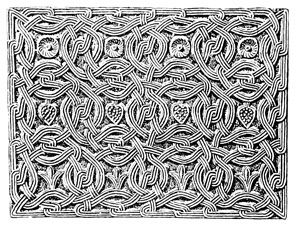

| Comacine Panel from the Church of San Clemente, Rome | To face page | 9 |

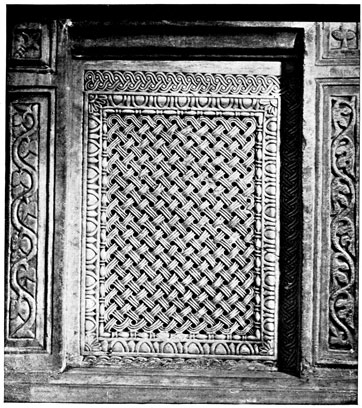

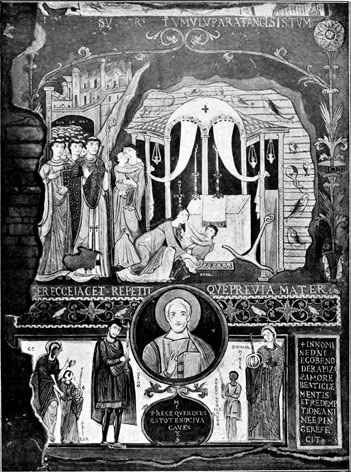

| Frescoes in the Subterranean Church of San Clemente, Rome | " | 10 |

| Church of Sta. Costanza, Rome | " | 12 |

| Door of the Church of S. Marcello at Capua | " | 13 |

| Ancient Sculpture in Monza Cathedral | " | 38 |

| Comacine Capital in San Zeno, Verona | " | 44 |

| Basilica of S. Frediano at Lucca | " | 50 |

| Façade of San Michele at Pavia | " | 52 |

| Tracing of an old print of the Tosinghi Palace, a mediæval building once in Florence, with Laubia on the front | " | 60 |

| Tower of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Rome | " | 64 |

| Byzantine Altar in the Church of S. Ambrogio, Milan | " | 74 |

| Fresco in the Spanish Chapel, S. Maria Novella, Florence | " | 78 |

| Door of the Church of San Michele, Pavia | " | 80 |

| Comacine Knot on a panel at S. Ambrogio, Milan | " | 82 |

| Sculpture from Sant' Abbondio, Como | " | 82 |

| Pulpit in the Church of S. Ambrogio, Milan | " | 88 |

| Door of a Chapel in S. Prassede, Rome | " | 90 |

| Pluteus from S. Marco dei Precipazi, now in S. Giacomo, Venice. | " | 90 |

| Comacine Capitals | " | 96 |

| Exterior of San Piero a Grado, Pisa | " | 102 |

| Comacine Capital in San Zeno, Verona, emblematizing Man clinging to Christ (the Palm) | " | 110 |

| Capital in the Atrium of S. Ambrogio, Milan | " | 112 |

| The West Door, St. Bartholomew, Smithfield | " | 122 |

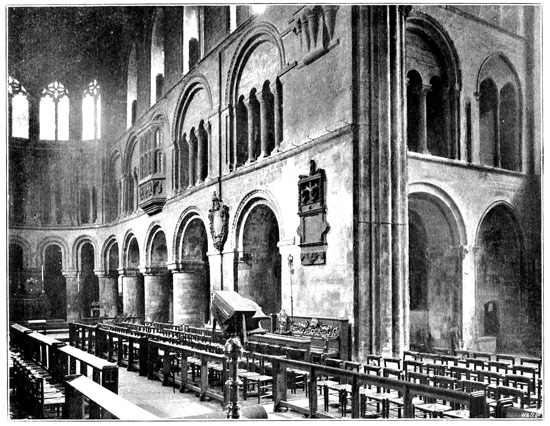

| South Side of the Choir, St. Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield | " | 124 |

| Palazzo del Popolo and Palazzo Comunale, Todi | " | 136 |

| Fiesole Cathedral. Interior | " | 145 xii |

| S. Clemente, Rome. Interior showing ancient screen | " | 146 |

| Tower of S. Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna | " | 153 |

| Tower of S. Satyrus. Milan | " | 154 |

| S. Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna | " | 157 |

| Door of the Church of S. Zeno at Verona | " | 166 |

| Baptistery at Parma, designed by Benedetto da Antelamo | " | 186 |

| Façade of Ferrara Cathedral | " | 198 |

| Church of S. Antonio, Padua | " | 200 |

| Tomb of Can Signorio degli Scaligeri at Verona | " | 204 |

| Interior of Pisa Cathedral | " | 212 |

| Pulpit in the Church of S. Giovanni Fuorcivitas, Pistoja | " | 222 |

| Church of S. Michele, Lucca | " | 226 |

| Cathedral of Lucca (San Martino) | " | 228 |

| Pulpit in Church of S. Bartolommeo, Pistoja | " | 230 |

| Church of S. Andrea, Pistoja | " | 234 |

| Church of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, Pistoja | " | 236 |

| Church of S. Maria, Ancona | " | 242 |

| Door of S. Giusto at Lucca | " | 244 |

| Pilaster of the Door of the Cathedral of Beneventum | " | 246 |

| Baptismal Font in Church of S. Frediano, Lucca | " | 248 |

| Pulpit in the Church of Groppoli near Pistoja | " | 249 |

| Pulpit in Siena Cathedral | " | 250 |

| The Riccardi Palace, built for Lorenzo dei Medici | " | 252 |

| Tomb of Mastino II. degli Scaligeri, at Verona | " | 254 |

| Capital of a Column in the Ducal Palace, Venice | " | 256 |

| Doorway of the Municipal Palace at Perugia | " | 258 |

| Palazzo Pubblico at Perugia | " | 260 |

| Court of the Bargello, Florence | " | 262 |

| Tower of Palazzo Vecchio at Florence | " | 263 |

| Eighth-century Wall Decoration in Subterranean Church of S. Clemente, Rome | " | 266 |

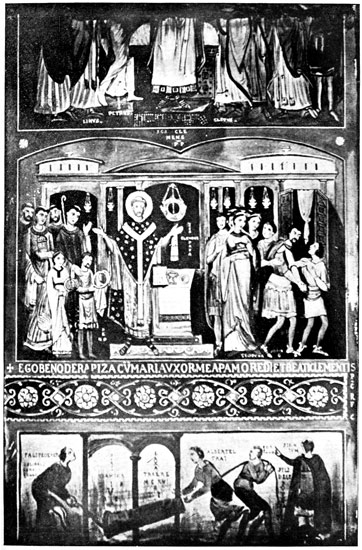

| Frescoes of the eighth century in the Subterranean Church of S. Clemente, Rome, with portraits of the Patron Beno di Rapizo and his Family | " | 268 |

| Interior of Church of San Piero a Grado near Pisa, with Frescoes of the ninth century | " | 270 |

| Figures from paintings in Assisi by Magister Giunta of Pisa | " | 272 |

| Fresco at S. Gimignano | " | 278 |

| Front of Siena Cathedral | " | 296 |

| Door in Orvieto Cathedral | " | 300 |

| Monument to Cardinal de Braye | " | 314 |

| Palazzo Vecchio, Florence | " | 316 |

| Shrine in Or San Michele, Florence | " | 332 |

| Small Cloister of the Certosa of Pavia | " | 358 xiii |

| Marble Work on the Roof of Milan Cathedral | " | 364 |

| Capital in Milan Cathedral | " | 366 |

| North Door of Como Cathedral, sculptured by Tommaso Rodari | " | 368 |

| Renaissance Front of the Church of the Certosa at Pavia | " | 378 |

| Façade of Monza Cathedral | " | 380 |

| The Cathedral and Broletta at Como | " | 382 |

| The Ca d'Oro, Venice | " | 388 |

| Ducal Palace at Venice. The side built by the Buoni Family | " | 390 |

| Court of the Ducal Palace at Venice | " | 392 |

| Apse of the Church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo on the Cœlian Hill, Rome | " | 404 |

| Basilica of S. Paolo fuori le mura, Rome | " | 406 |

| Pulpit in Church of S. Cesareo in Palatio, Rome. Mediæval Sculpture inlaid in Mosaic | " | 408 |

| Candelabrum in S. Paolo at Rome | " | 412 |

THE CATHEDRAL BUILDERS

In looking back to the great church-building era, i.e. to the centuries between 1100 and 1500, do not the questions arise in one's mind, "How did all these great and noble buildings spring up simultaneously in all countries and all climates?" and "How comes it that in all cases they were similar to each other at similar times?"

In the twelfth century, when the Italian buildings, such as the churches at Verona, Bergamo, Como, etc., were built with round arches, the German Domkirchen at Bonn, Mayence, Treves, Lubeck, Freiburg, etc.; the French churches at Aix, Tournus, Caen, Dijon, etc.; and the English cathedrals at Canterbury, Bristol, Chichester, St. Bartholomew's in London—in fact, all those built at the same time—were not only round-arched, but had an almost identical style, and that style was Lombard.

In the thirteenth century, when pointed arches mingled with the round in Italy, the same mixture is found contemporaneously in all the other countries.

Again in the fourteenth century, when Cologne, Strasburg, and Magdeburg cathedrals were built in pure Gothic; then those of Westminster, York, Salisbury, etc., arose in England; the Domes of Milan, Assisi, and 4 Florence in Italy; and the churches of Beauvais, Laon, and Rouen in France. These all came, almost simultaneously, like sister buildings with one impronto on them all.

Is it likely that many single architects in different countries would have had the same ideas at the same time? Could any single architect, indeed, have designed every detail of even one of those marvellous complex buildings? or have executed or modelled one-tenth of the wealth of sculpture lavished on one of those glorious cathedrals? I think not.

The existence of one of these churches argues a plurality of workers under one governing influence; the existence of them all argues a huge universal brotherhood of architects and sculptors with different branches in each country, and the same aims, technique, knowledge and principles permeating through all, while each conforms in detail to local influences and national taste.

If we once realize that such a Guild must have existed, and that under the united hands of the grand brotherhood, the great age of church-building was endowed with monuments which have been the glory of all ages, then much that has been obscure in Art History becomes clear; and what was before a marvel is now shown to be a natural result.

There is another point also to be considered. The great age of church-building flourished at a time when other arts and commerce were but just beginning. Whence, out of the dark ages, sprang the skill and knowledge to build such fine and sculpturesque edifices, when other trades were in their infancy, and civic and communal life scarcely organized?

It is indeed a subject of wonder how the artists of the early period of the rise of Art were trained. Here we find men almost in the dark ages, who were the most splendid 5 architects, and at the same time sculptors, painters, and even poets. How, for instance, did Giotto, a boy taken from the sheep-folds, learn to be a painter, sculptor, and architect of such rank that the city of Florence chose him to be the builder of the Campanile? Did he learn it all from old Cimabue's frescoes, and half Byzantine tavole? and how did he prove to the city that he was a qualified architect? We find him written in the archives as Magister Giotto, consequently he must have passed through the school and laborerium of some guild where every branch of the arts was taught, and have graduated in it as a master.

All these things will become more and more clear as we follow up the traces of the Comacine Guild from the chrysalis state, in which Roman art hybernated during the dark winter of the Middle Ages, through the grub state of the Lombard period, to the glorious winged flights of the full Gothic of the Renaissance.

And first as to the chrysalis, at little Como. The origin of the name Comacine Masters has caused a great deal of argument amongst Italian writers new and old. Some think it merely a place-name referring to the island of Comacina, in Lake Lario or Como; others take a wider significance, and say it means not only the city of Como, but all the province, which was once a Roman colony of great extension. Others again, among whom is Grotius, suggest that it is not a place-name at all, but comes from the Teutonic word Gemachin or house-builders. As the Longobards afterwards called them in Italian Maestri Casarii, which means the same thing, there is perhaps something to be said for this hypothesis.

The first to draw attention to the name Magistri Comacini, was the erudite Muratori, that searcher out of ancient MSS., who unearthed from the archives an edict, dated November 22, 643, signed by King Rotharis, in which 6 are included two clauses treating of the Magistri Comacini and their colleagues. The two clauses, Nos. 143 and 144, out of the 388 inscribed in crabbed Latin, are, when anglicized, to the following intent—

"Art. 143. Of the Magister Comacinus. If the Comacine Master with his colliganti (colleagues) shall have contracted to restore or build the house of any person whatsoever, the contract for payment being made, and it chances that some one shall die by the fall of the said house, or any material or stones from it, the owner of the said house shall not be cited by the Magister Comacinus or his brethren to compensate them for homicide or injury; because having for their own gain contracted for the payment of the building, they must sustain the risks and injuries thereof."[2]

"Art. 144. Of the engaging or hiring of Magistri. If any person has engaged or hired one or more of the Comacine Masters to design a work (conduxerit ad operam dictandum), or to daily assist his workmen in building a palace or a house, and it should happen that by reason of the house some Comacine should be killed, the owner of the house is not considered responsible; but if a pole or a stone shall kill or injure any extraneous person, the Master builder shall not bear the blame, but the person who hired him shall make compensation."[3]

These laws prove that in the seventh century the Magistri Comacini were a compact and powerful guild, capable of asserting their rights, and that the guild was properly organized, having degrees of different ranks; that the higher orders were entitled Magistri, and could "design" or "undertake" a work;—i.e. act as architects; and that the colligantes worked under, or with, them. In fact, a powerful organization altogether;—so powerful and so solid, that it speaks of a very ancient foundation.

But when and how did it originate?

Was it a surviving branch of the Roman Collegium? a decadent group of Byzantine artists stranded in Italy? or was it of older Eastern origin? A clever logician could prove it to be all three.

For the Roman theory, he could base his arguments on the Latin nomenclature of officials, and the Latin form of the churches.

For the Byzantine theory, he would have the style of certain ornamentations, and the assertions of German writers, such as Müller, and Stieglitz.

For the ancient Eastern theory, he might plead their Hebrew and Oriental symbolism.

We will take the Byzantine theory first. Müller (Archaeologie der Kunst, p. 224) says that: "From Constantinople as the centre of mechanical skill, a knowledge of art radiated to distant countries, corporations of builders of Grecian birth were permitted to exercise a judicial government among themselves according to the laws of the country to which they owed allegiance;" and Stieglitz, in his History of Architecture, records a tradition that at the time the Lombards were in possession of Northern Italy, i.e. from the sixth to the eighth century, the Byzantine builders 8 formed themselves into guilds and associations, and that on account of having received from the Popes the privilege of living according to their own laws and ordinances, they were called Freemasons.[4] Italian and Latin writers, however, place the advent of these Greek artists at a later period; they are supposed to have been sculptors, who, rebelling against the strict Iconoclasm of Leo, the Isaurian—718 A.D. to 741—came over to Italy where art was more free, and joined the Collegia there.

But at this time most of the chief Longobardic churches were already built by the Comacine Masters, and were Roman in form, mediæval in ornamentation, and full of ancient symbolism. Herr Stieglitz must have pre-dated his tradition. Besides this I can find no sign in Italian buildings, or writers about them, of any lasting Byzantine influence. Indeed pure Byzantine architecture in Italy seems sporadic and isolated, not only in regard to site, but in regard to time. The Ravenna mosaics, a few in Rome, a little work in Venice, is all one can call absolutely Byzantine; and the influence never spread far. The Comacine ornamentation indeed has qualities utterly distinct in spirit, though in some of its forms allied to Byzantine. It is possible that some of these Eastern exiles joined the Comacine Guild, but there is quite enough in the communications of Como with the Greeks, to account for their having imbibed as much as they did of Byzantine style. Some of the Bishops who were rulers of Como before and after Lombard times were Greeks; notably Amantius the fourth, who was translated there from Thessalonica, and his successor, S. Abbondio. Also through the Patriarch of Aquileja, under whose jurisdiction they were brought later, the guild was put into contact with the Greek sculptors then at Venice, Grado, and Ravenna.

Comacine Panel from the Church of San Clemente, Rome. The Lattice-work is made of a single strand interlaced. Date, 6th century.

We will leave the Oriental theory aside as too vague and traditional for proof, depending as it does on a few Oriental symbols, and certain forms of decoration, and will look nearer home—even to Rome, with which a connection may certainly be found, and that in a form visible to our modern eyes.

Rome is almost as full of remains of what is now styled Comacine architecture, as it is of classic and pagan ruins, and they are nearly as deeply buried. Go where you will, and in the vestibules or crypts of churches, now of gaudy Renaissance style, you will find the sign and seal of the ancient guild. Investigate any church which has a Lombard tower—and they are many—and you will discover that the hands which built that many-windowed tower have left their mark on the church. In that wonderful third-century basilica, which was discovered beneath the thirteenth-century one of S. Clemente; in the almost subterranean basilica of S. Agnese fuori le mura; in the vestibule of the florid modern SS. Apostoli; in Santa Maria in Cosmedin; and various other buildings, are wonderful old slabs of marble with complicated Comacine knots on them. Our illustration is from a slab in San Clemente, which was evidently from the buried church, though used as a panel in the parapet of the existing choir. A marvellous piece of basket-work in marble, which, if studied, will be found composed of a single cord, twined and intertwined. An almost identical panel is preserved in the wall of the staircase to S. Agnese, another has just been found reversed, and the back of it used for the thirteenth-century mosaic decoration of the pulpit in S. Maria in Cosmedin.

Then in the later Lombard churches of S. Lorenzo in Lucina, SS. Giovanni e Paolo, S. John Lateran, etc., one may see the crouching Comacine lions, now mostly minus their pillars, and shoved under square door-lintels, or built into walls, where they remain to tell of the ancient builders whose sign and seal they were. 10

And here and there we get a name.

In the vestibule of the SS. Apostoli is a red marble lion, on the base of which in Gothic letters is the name BASSALECTI. Beneath it is an old inscription, "Opus magister Bassalecti Marmorari Romano sec, XIII." This same Magister's name, spelt Vassalecti, has lately been discovered inscribed on the capitals of some columns in the nave of S. John Lateran.

In the under church of S. Clemente, an ancient fresco of the eighth century takes us further back than this. Here we see a veritable Roman Magister directing his men. He stands in magisterial toga (and surely one may descry a masonic apron beneath it!), directing his men in the moving of a marble column, and with the naïve simplicity of the primitive artist each man's name is written beside him. Albertel and Cosmaris are dragging up the column with a rope, the sons of Pute, who are possibly novices, are helping them, while Carvoncelle is lifting it from behind with a lever. These men are all in short jerkins, but the master, Sisinius, is standing in his toga, directing them with outstretched hand.

Here is the Magister of a Roman Collegium embalmed and preserved for us, that we may see him and his men at work as they were in the early centuries after Christ. We know that Masonic Collegia were still existing in Rome in the time of Constantine and Theodosius; we know that Constantine built the basilica of S. Agnese, afterwards restored by Pope Symmachus; also those of S. Lorenzo—at least the round-arched part of it—enlarged by Galla Placidia in the fifth century; S. Paolo fuori le Mura, and other ancient churches. We see from remains recently brought to light, that these were originally of the exact plan of the churches built "in the Roman manner" at Hexham and York in England, and of the Ravenna churches, and S. Pietro in Grado at Pisa, also nearly contemporary. We 11 further realize that all of these were identical in style with the finer specimens of Lombard building some centuries later. There is only the natural decline of art which would have taken place in the century or two of barbarian invasion, between the two epochs, but the traditionary forms, methods, etc., are all reproduced in the Lombard-Comacine churches. Compare the fourth-century door of the church of S. Marcello at Capua with the eighth-century one of S. Michele at Pavia, and you will find precisely the same style of art. Compare the Roman capitals of the church of Santa Costanza, built by Constantine, with the capitals in any Comacine church up to 1200, and you will see the same mixture of Ionic and a species of Corinthian with upstanding volutes. Some of the Comacine buildings have these upright volutes plain instead of foliaged. The effect is rude, but I think these plainer capitals were not a sign of incapacity in the architects of the guild, for one sees richly ornate ones on the same building. It was only the stock design of the inferior masters, when funds did not allow of payment for richer work.

Frescoes in the Subterranean Church of San Clemente, Rome. Upper line, Byzantine, 4th century; under ones, Comacine, 8th century.

Therefore it may be inferred: (1) That architects of the same guild worked in Rome and in Ravenna in the early centuries after Christ; (2) that though the architects were Roman, the decorators up to the fourth century were chiefly Byzantine, or had imbibed that style as their paintings show; (3) that in the time when Rome lay a heap of ruins under the barbarians, the Collegium, or a Collegium, I know not which, fled to independent Como; and there in after centuries they were employed by the Longobards, and ended in again becoming a powerful guild.

Hope, the author of an historical Essay on Architecture, had a keen prevision of this guild, although he had no documents or archives, but only the testimony of old stones and buildings to prove it. After sketching the formation of the Roman Collegia, and the employment of 12 their members as Christian architects under the early Popes, he says "that a number of these, finding their work in Rome gone in the times of invasion, banded together to do such work in other parts of the world." He seems to think that the nucleus of this union was Lombardy, where the superiority of the architecture, under the Lombard kings, was such that the term Magistri Comacini became almost a generic name for architects. He says that builders and sculptors formed a single grand fraternity, whose scope was to find work outside Italy. Indeed distance and obstacles were nothing to them; they travelled to England under Augustine, to Germany with St. Boniface, to France with Charlemagne, and again to Germany with their brother magister, Albertus Magnus; they went to the east under the Eastern Emperors, to the south under the Lombard Dukes, and in fact are found everywhere through many centuries. The Popes, one after another, gave them privileges. Indeed the builders may be considered an army of artisans working in the interest of the Popes, in all places where the missionaries who preceded them had prepared the ground for them.

Diplomas and papal bulls confirmed to the guild the privileges they had obtained under their national sovereigns, and besides guaranteed their safety in every Catholic country which they visited for the scope of their association. They assumed the right to depend wholly and solely on the Pope, which absolved them from the observance of all local laws and statutes, royal edicts, and municipal regulations, and released them from servitude, as well as all other obligations imposed on the people of the country. They had not only the power of fixing their own honorarium, but the exclusive right of regulating in their own lodges everything that appertained to their own internal government. Those diplomas and bulls prohibited any other artist, extraneous to the guild, from establishing any kind of competition with them.... Encouraged by such a special protection, the 13 Romans in great numbers entered the Masonic Guild, particularly when they were destined to accompany the missionaries sent by the Pope to countries hitherto unvisited by them. The Greeks also did not delay to take part. The Exarchate of Ravenna, first detached from the Greek Empire by the power of the Lombard princes, had by King Pepin been given to the Popes.... The commercial relations and communications of all kinds maintained with Constantinople by the many cities of Northern Italy, daily attracted many Greeks to this city; finally, the political turbulence of Constantinople, and chiefly the fanaticism of the Iconoclasts, continued to associate Greek artists with Italy, and many of these were received in the lodges, whose number constantly increased.

As civilization became more diffused, the inhabitants of northern countries, French, Germans, Belgians, and English, were admitted to form part of these guilds. Without this concession they would probably have had to fear a perilous competition, encouraged by the sovereigns of other countries.... These corporations were always in league with the Church, which in those times of war and constant struggle, of military service and feudal slavery, was the only asylum for those who wished to cultivate the arts of peace. Therefore we see ecclesiastics of high rank, abbots, prelates, bishops, exalting the respect in which the Freemasons were held, by joining the guild as members. They gave designs for their own churches, overlooked the building, and employed their own monks in the manual labour.

Such is broadly the substance of Hope's account of the great Lombard Guild. It shows remarkable insight, for when he wrote, the documentary evidences which have lately been collected were wanting.[5] It also explains precisely the close connection with monks and the Church, 14 which appears in all the story of the guild, and it accounts for the Greek influence in the ornamentation.

In all the course of the history of building we see that each country or province had to obtain its architects from this Collegium at Rome, as Villani says all the cities of Italy did, and were obliged to apply to the Grand Master of the whole guild. Thus the early Popes had to beg architects for Rome from the Lombard kings; Pope Adrian had to apply to Charlemagne for builders; and so on up to the time when all the church-building Communes had to seek architects from some existing lodge.

Giovanni Villani shows us the intimate connection of the Roman Collegium with Florence. He says that after Cæsar had destroyed Fiesole he wished to build another city to be called Cesaria, but the Senate would not permit this. The Senate, however, gave his Generals Macrinus, Albinus, Cneus Pompey, and Martius equal power to build, and between them they founded Florence, bringing the water from Monte Morello by an aqueduct. Villani says the Magistri came from Rome for all these works. That was in the days when the great masonic company had their Grand Lodge in Rome, before the martyrdom of the Santi Quattro, afterwards their patron saints.

In Chapter XLII. Villani relates how when the citizens of Florence wished to build a temple to Mars, they sent to the Senate of Rome to beg that they would supply the most capable and clever Magistri that Rome could furnish. This was done,[6] and the Baptistery was erected in its first form.

Again whilst Charlemagne and Pope Adrian were employing the Comacines to rebuild the ruins of Rome, we find from Villani (lib. iii. chap. 1) that Charlemagne 15 sent some Romans with "all the masters there were in Rome" (e vennero con quanti maestri n'avea in Roma per più tosto murarla) to fortify Florence, which had appealed to him for succour against the Fiesolans. In this manner, says Villani, "the Magistri who came with the Romans began to rebuild our noble city of Florence."

As early as the fifth century Cassiodorus seems to refer to the work of the Comacines when writing about the "public architects"—the very expression implies a public company—and admiring the grand Italian edifices with their "airy columns, slight as canes," he adds, "to be called Magister is an honour to be coveted, for the word always stands for great skill."[7]

This brings us to the question of the Latin nomenclature. No really qualified Comacine architect is ever mentioned either in sculptured inscription, parchment deed, or in the registers of the lodges, without the prefix Magister, a title which Cassiodorus, for one, respected. It was not a term applied indiscriminately to all builders, like murarius; and we find that the subordinate ranks of stone-cutters or masons were called by the generic name of operarius. I take it that the word, as applied to the higher rank of the Comacine Guild, has the same value as the title of Master in the old trade guilds of London, i.e. one who has passed through the lower rank of the schools and laborerium, and has by his completed education risen to the stage of perfection, when he may teach others.

Morrona[8] gives the same definition. Judging from ancient inscriptions and documents, he says that "operator" (Latin operarius) is used for one who works materially; while Magister signifies the architect who designs and commands. When a Magister carries out his own designs, 16 he is said to be operator ipse magister, as in the case of Magister Rainaldus, who designed and sculptured the façade of the Duomo at Pisa.

In warlike times such as the Middle Ages, the only means by which artisans could protect their interests was by mutual protection, and hence the necessity and origin of Trade Guilds in general. The Masonic one appears to have been a universal fraternity with an earlier origin; indeed many of their symbols point to a very ancient Eastern derivation, and it is probable it was the prototype of all other guilds.

Since I began writing this chapter a curious chance has brought into my hands an old Italian book on the institutions, rites, and ceremonies of the order of Freemasons.[9] Of course the anonymous writer begins with Adoniram, the architect of Solomon's Temple, who had so very many workmen to pay, that not being able to distinguish them by name, he divided them into three different classes, novices, operatori, and magistri, and to each class gave a secret set of signs and passwords, so that from these their fees could be easily fixed, and imposture avoided. It is interesting to know that precisely the same divisions and classes existed in the Roman Collegium and the Comacine Guild—and that, as in Solomon's time, the great symbols of the order were the endless knot, or Solomon's knot, and the "Lion of Judah."

Our author goes on to tell of the second revival of Freemasonry, in its present entirely spiritual significance, and he gives Oliver Cromwell, of all people, the credit of this revival! The rites and ceremonies he describes are the greatest tissue of mediæval superstition, child's play, blood-curdling oaths, and mysterious secrecy with nothing to 17 conceal, that can be imagined. All the signs of masonry without a figment of reality; every moral thing masquerades under an architectural aspect, in that "Temple made without hands" which is figured by a Freemasons' lodge in these days. But the significant point is that all these names and masonic emblems point to something real which existed at some long-past time, and, as far as regards the organization and nomenclature, we find the whole thing in its vital and actual working form in the Comacine Guild. Our nameless Italian who reveals all the Masonic secrets, tells us that every lodge has three divisions, one for the novices, one for the operatori or working brethren, and one for the masters, besides a meeting or recreation room; and that no lodge can be established without a minimum of two masters. Now wherever we find the Comacines at work, we find the threefold organization of schola or school for the novices, laborerium for the operatori, and the Opera or Fabbrica for the Masters of Administration.

The anonymous one tells us that there is a Gran Maestro or Arch-magister at the head of the whole order, a Capo Maestro or chief Master at the head of each lodge. Every lodge must besides be provided with two or four Soprastanti, a treasurer, and a secretary-general, besides accountants. This is precisely what we find in the organization of the Comacine Lodges. As we follow them through the centuries we shall see it appearing in city after city, at first dimly shadowed where documents are wanting, but at last fully revealed by the books of the treasurers and Soprastanti themselves, in Siena, Florence, and Milan.

Thus, though there is no certain proof that the Comacines were the veritable stock from which the pseudo-Freemasonry of the present day sprang, we may at least admit that they were a link between the classic Collegia and all other art and trade guilds of the Middle Ages. They were called Freemasons because they were builders of a 18 privileged class, absolved from taxes and servitude, and free to travel about in times of feudal bondage. The term was applied to them both in England and Germany. Findel quotes two old English MSS., one of 1212, where the words "sculptores lapidum liberorum" are in close conjunction with cœmentari, which is the oldest Latin form for builder; and another dated 1396, where occurs the phrase "latomos vocatos fremaceons." In the rolls of the building of Exeter and Canterbury cathedrals the word Freimur is frequent, and no better proof can be given of the way the early Masonic guild came into England. The Italian term liberi muratori went into Germany with the Comacine Masters, who built Lombard buildings in many a German city, before Gothic ones were known; thence it passed Teutonized as Freimur into England.[10]

Cesare Cantù (Storia di Como, vol. i. p. 440) thus describes the Guild—

"Our Como architects certainly gave the name to the Masonic companies, which, I believe, had their origin at this time, though some claim to derive them from Solomon. These were called together in the Loggie (hence Lodge) by a grand-master to treat of affairs common to the order, to accept novices, and confer superior degrees on others. The chief Lodge had other dependencies, and all members were instructed in their duties to the Society, and taught to direct every action to the glory of the Lord and His worship; to live faithful to God and the Government; to lend themselves to the public good and fraternal charity. In the dark times which were slowly becoming enlightened, they communicated to each other ideas on architecture, buildings, stone-cutting, the choice of materials and good taste in design. Strength, force, and beauty were their symbols. Bishops, princes, men of high rank who studied architecture fraternized with them, but the mixture of so many different classes changed in time the spirit of the Freemasons. The original forms of building were lost when the science fell into the hands and caprice of venal artisans."[11]

We shall see the way in which the Comacines spread fraternity wherever they went. When they began building in any new place, they generally founded a lodge there, which comprised a laborerium and school. Thus we find one under the Antellami family in Parma before 1200, and not long after one in Modena under the same masters from Campione. The lodge is clearly defined at Orvieto 20 and Siena. In Lucca there was a laborerium before the year 1000. In 1332 it had obtained privileges. At Milan there was evidently another, for on February 3, 1383, the archbishop invites the architects Fratelli (brethren), and others who understand the work, to inspect the models for the cathedral; now these words evidently refer to a Masonic brotherhood, as does the term Opera Magiestatem so often met with in old documents.

In the Marches of Ancona is a sepulchre inscribed to the fratres Comacini, and in the Abruzzi are chapels dedicated by them. In Rome it is recorded that they met in the church of SS. Quattro Coronati. These patron saints of the guild, the four holy crowned ones (Santi Quattro Coronati), strike me as having a peculiar significance in regard to their origin. We are told that during the persecutions under Diocletian, four brethren, named Nicostratus, Claudius, Castorio, and Superian[12] (either brothers, or more likely members of the same Collegium), who were famous for their skill in building and sculpture, refused to exercise their art for the pagan Emperor. "We cannot," they said, "build a temple for false gods, nor shape images in wood or stone to ensnare the souls of others." They were all martyred in different ways: one scourged, one shut up and tortured in an iron case, one thrown into the sea; the other was decapitated. Their relics were in the time of St. Leo placed in four urns, and deposited in the crypt of the church, which was built to their honour, in the time of Honorius, by the Comacines then in Rome. It has always been the especial church of the guild, and their meeting-place. They had an altar dedicated to the same saints at Siena, and another at 21 Venice. We find from the statutes of the Sienese guild as late as the fourteenth century, that the fête of the "Quattro" was kept in a special manner by the Masonic guild. All the Church fêtes are classed together as days when no work is to be done, but the day of the SS. Quattro has two laws all to itself, and is kept with peculiar ceremonies.[13]

On the altar of this church on Mount Aventine are silver busts of the four Magister martyrs; and on the wall is an ancient inscription, as follows—

BEATVS LEO IIII PAPA

PARITER SVB HOC SACRO ALTR̄

REC̄DENS COLLOCAVĪ CORPOR̄ SCŌ

M͞R CLAVDII NICOSTĪ SEMPRON̄I

CAST̄ ET SIMP̄ ET HII FR̄M SEVERI

SEVERIANI CARPOFORI ET VICTO

RINI MARII AVDIFAX EABBACV̄

FELICISSIMO ET AGAPITO YPPOLT̄

OVDE CV̄ SVA FAM̄L NV̄O X ET

VIIII ACQVILINI ET PRISCI ARSEI

AQVNI NARCISI ET MARCELLI

NI FELICIS SIMETRII CANDI

DAE ATO PAVLINÆ ANASTASII

ET FELICIS APOLLIONIS

ET BENEDICTI VENANTII

ATO FELICIS DIOGENIS ET LI

BERALIS FESTI ET MARCELLI

ATO SVPERANTII PVDENTIAN̄E

ET BENEDICTI FELICIS ET BENE

DICTI NECN̄ CAPITA SANCTO

PROTI SC̄EO CECILIA E

SC͞I ALEXANDRI SC̄IO XISTI

ET SC͞I SEBASTIANI ATQ

SACRATISSIME VIRGINIS

PRAXEDIS ET ALIA MVLTA

CORPORA SANCTORVM

QVORVM NOMINA DEO

SVNT COGNITA

If I interpret the abbreviations M͞R. F͞RM and FA͞ML aright, this inscription would imply that members of each of the three grades of the Roman Masonic guild, Magister, Fratres, and Famuli (apprentices), were martyred together, and their remains placed in this church with the relics of some proto-martyrs. The Magistri were afterwards canonized, and the four I have named became the patron saints of the guild. S. Carpophorus was held in special veneration in Como, of which place he was probably a native, or else a Greek member of the Comacine Lodge there.

The other side of the inscription chronicles the restoration of the altar which was ruined and broken down, in the time of Pope Paschalis Secundus, A.D. 1111, in the fourth Indiction.

The church of the SS. Quattro has remains of a fine atrium or portico. In the wall of the atrium is a fragment of intreccio. The original form of the church is well preserved, and is identical with that of S. Agnese, fuori le mura. The gallery for the women is well preserved.

The especial veneration for the four crowned martyrs seems to point to their Roman origin, and to specify the reason why the remnant of the particular Collegium to which they belonged fled from Rome, and took refuge in the safe little republic of Como, so that it was not only the Goths and Vandals from whom they fled. It explains also the intense religion in their work, and rules; 23 the very first principles of which were to respect God's name, and do all to His glory.

It need not excite wonder that any guild should have fled from Rome in these centuries. This was the time that Gregory the Great, painted so graphically in his passionate Homily of Ezechiel, preached at Rome. "Everywhere see we mourning, hear we laments; cities, strongholds, villages are devastated; the earth is a desert. No busy peasants are in the fields, few people in the cities, and these last relics of human kind daily suffer new wounds. There is no end to the scourging of God's judgment.... We see some carried into slavery, others cruelly mutilated, and yet more killed. What joy, oh my brethren, is left to us in life? If it is still dear to us we must look for wounds, and not for pleasures. Behold Rome, once Queen of the world, to what is she reduced?—prostrated by the sorrows and desolation of her citizens, by the fierceness of her enemies and frequent ruin, the prophecy against Samaria has been fulfilled in her. Here no longer have we a senate; the people are perished, save the few who still suffer daily. Rome is empty, and has barely escaped the flames; her buildings are thrown down. The fate of Nineveh is already upon her...."[14]

The Longobard invaders were more merciful than the Goths, for not long after their rule was over, another Pope wrote to Pepin—"Erat sanæ hoc mirabile in regno Longobardorum, nulla erat violenta nulla struebantur insidiæ. Nemo aliquem iniuste angariabat, nemo spoliabat. Non erat furta, non latrocinia, unusquisque quodlibebat securus sine timore pergebat."—Histor. Franc. Scrip. Tom. III. cap. xvi.

Whatever the moving cause, the fact remains that in the Middle Ages the Comacine Masters had a nucleus on that strong little fortified island of Comacina, which, together 24 with Como itself, stood against the Lombards in the sixth century for twenty years before being subjugated; and in the twelfth, held its own independence for a quarter of a century against Milan and the Lombard League, which it refused to join.

When at length the Longobards became their rulers, they respected their art and privileges. The guild remained free as it had been before, and in this freedom its power must have increased fast.

The Masters worked liberally for their new lords, but it was as paid architects, not as serfs. As a proof we may cite an edict signed by King Luitprand on February 28, 713. It is entitled Memoratorio, and is published by Troya in his Codex Diplomaticus Longobardus.

It fixes the prices of every kind of building. Here are the titles of the seven clauses, referring to the payments of the Magistri Comacini: De Mercede Comacinorum—

CLVII. Capit. i. De Sala. "Si sala fecerit, etc."

CLVIII. Capit. ii. De Muro. "Si vero murum fecerit qui usque ad pedem unum sit grossus ... cum axes clauserit et opera gallica fecerit ... si arcum volserit, etc."

Capit. iii. De annonam Comacinorum.

CLIX. Capit. iv. De opera.

CLX. Similiter romanense si fecerit, sic repotet sicut gallica opera.

Capit. v. De Caminata.

CLXI. Capit. vi. De marmorariis.

CLXII. Si quis axes marmoreas fecerit ... et si columnas fecerit de pedes quaternos aut quinos ...

Capit. vii. De furnum.

CLXIII. Capit. viii. De Puteum. Si quis puteum fecerit ad pedes centum.[15]

The Longobard rule explains why the Comacine Masters of the thirteenth century were known as Lombards, and the architecture of that time as the "Lombard style." In the same way they were called Franchi when Charlemagne was their king; and Tedeschi when the German dynasty conquered North Italy; if indeed the words artefici Franchi do not merely signify Freemasons, which I strongly suspect is the true meaning.

To understand the connection of this guild of architects with little Como we must glance backwards at the state of that province under the Romans, when it was a colony ruled by a prefect. Junius Brutus himself was one of these rulers, and Pliny the Younger a later one. At this time Como was a large and flourishing city. It had in Cæsar's time a theatre whose ruins were found near S. Fedele; a gymnasium for the games, which was near the present church of Santa Chiara. A document dated 1500 speaks of the Arena of Como as then still existing. The campus martius was at S. Carpoforo, where several Roman inscriptions, urns, and medals were found. This valuable collection of Latin inscriptions, found in and about Como, proves the successive rule of emperors, prefects, military tribunes, naval prefects, Decurions, etc. We have records also of Senators, Decemviri, and other municipal magistrates. The inscriptions also show that there were temples to Jove, Neptune, the Dea Bona, the Manes, the Dea Mater, Silvanus, Æsculapius, Mars, Diana, Hygeia, and even Isis.

Some Cippi are dedicated to Mercury and Hercules; and one found near S. Maria di Nullate was inscribed by order of the Comacines to Fortuna Obsequente, "for the health of the citizens." To this day a Prato Pagano 26 (pagan field) exists near Como. All these proofs, together with Pliny's testimony, go to show that Como was in Roman times an important centre, and as such was likely to have its own Collegia or trade guilds, to one of which probably Pliny's builder, Mustio, belonged, and to which the Roman refugees naturally fled as brethren.

Pliny the Younger at that time lived at Como, in his delightful villa, Comedia. In his grounds, on a high hill, were the ruins of the temple of the Eleusinian Ceres, and he determined to restore this temple, as devotees flocked there during the Ides of September, and had no refuge from sun or rain.[16] His letter to "Mustio," a Comacine architect, gives the commission for this restoration, and after explaining the form he wished the design to take, he concludes—"At least unless you think of something better, you, whose art can always overcome difficulties of position." For Pliny, fresh from Rome, to give such praise to an architect at Como, shows that even at that time good masters existed there.

Another letter of Pliny's (Lib. X. Epist. xlii.) speaks of the villa of his friend Caninus Rufus, on the same lake, with its beautiful porticoes and baths, etc., and of the many other villas, palaces, temples, forums, etc., which embellished Como and its neighbourhood.

Catullus lived here when the poet Cæcilius, whose works have now perished, invited him to leave the hills of Como, and the shores of Lario, to join him in Verona.

Pliny seems to confirm the existence of guilds,[17] as he speaks of the institution of a Collegium of iron-workers, who wished to be patented by the Emperor, but Trajan refused to form new guilds, for fear of the Hetæriæ or factions which might infiltrate into them.

Mommsen, in his work De Collegiis et Sodalitiis 27 Romanorum, says that under the emperors no guild was allowed to hold meetings, except by special laws, yet though new companies were not to be formed, the existing ones of architects and artisans were permitted to continue after public liberty was lost. Several documents prove that the chief scope of these unions was to promote the interests of their art, to provide mutual assistance in the time of need, to succour the sick and poor, and to bury the dead.

The trade guilds in London, the Arti in Florence, and the town clubs kept up in England till lately, seem to be all survivals of these ancient classical societies.

Besides the Builders' Society, Como had, in Roman times, a nautical guild. An inscription is extant, dedicated to C. Messius Fortunatus by the Collegium nautarum Comensium. This guild sent twenty ships of war to Venice in Barbarossa's time.

But besides having privileged societies, Como and its Comacine islands were a privileged territory, and might almost have been called a republic. We have, it is true, no documentary evidence of this dating back to pre-Longobardic times, but as Otho in 962[18] confirmed the islands in all former privileges granted by his predecessors on the Imperial throne, we may fairly suppose the privileges dated from times far anterior to himself.

This is an anglicized version of his decree, which was granted on the petition of the Empress Adelaide—

"In the name of the Holy and indivisible Trinity, Otho, by the will of God, august Emperor. If we incline to the demands of our faithful people, much more should we lend our ear to the prayers of our beloved consort. Know then, all ye faithful subjects of the Holy Church of God, present and future, that the august Empress Adelaide, 28 our wife, invokes our clemency, that for her sake we receive under our protection the inhabitants of the Comacine islands, and surrounding places known as Menasie (sic), and we confirm all the privileges which they have enjoyed under our predecessors, and under ourselves before we were anointed Emperor, viz. they shall not be called on for military service, nor have arbergario (taxes on roads and bridges), nor pay curatura (tax on beasts), terratico (tax on land), ripatico (on ships), or the decimazione (tax on householders) of our kingdom, neither shall they be obliged to serve in our councils, except the general assembly at Milan, which they shall attend three times a year. All this we concede, etc. Given on the 8th before the calends of September, in the year of the Incarnation 962, first year of the reign of the most pious Otho."—Indiction V. in Como.

The hypothesis that this decree refers to a long-existing liberty is confirmed by the history of Como in the time of Justinian I. Up to the middle of the sixth century a certain Imperial Governor of Insubria, named Francione, who had seen Rome sacked and his own state taken, fled to Comacina as a free place of refuge when Alboin invaded Italy. He helped the Comacines to hold out against the barbarians for more than twenty years, and so secure was the place considered that the island was by Narses and others made the depositary of infinite treasures. With him multitudes of Romans had taken refuge there, but finally even this fell into the hands of the Longobards. We are told that Autharis subjugated Istria, and after a six months' siege, possessed himself of the very strongly fortified island of Comacina on the lake of Como, where he found immense treasures, doubtless part of the traditional wealth amassed by Narses, and which as well as much private property had been deposited here for security by the neighbouring peoples.[19]

Here then, four centuries before Otho's decree, we have Comacina as a place of refuge in troublous times, chosen because, being a free city, it was considered more safe than other towns. We need not then consider it improbable, if in the dark centuries when the Roman Empire was dying out, and its glorious temples and streets falling into ruin under the successive inroads of half-savage despoilers; when the arts and sciences were falling into disuse or being enslaved; and when no place was safe from persecution and warfare, the guild of the Architects should fly for safety to almost the only free spot in Italy; and here, though they could no longer practise their craft, they preserved the legendary knowledge and precepts which, as history implies, came down to them through Vitruvius from older sources, some say from Solomon's builders themselves.

Among the treasures must have been works of Greek and Roman art, that kept alive the old spirit among the guild of builders gathered there; but alas! after the long generations when art was decaying, and uncalled for, their hands lost their skill, they could no longer reproduce the perfect works.

It was here the Longobards found them, and in their new Christian zeal soon furnished them with work enough. 30

LONGOBARD KINGS

| 568. | Alboin conquers Italy; he was poisoned by his wife Rosamund for compelling her to drink out of her father's skull. |

| 573. | Cleoph (assassinated). |

| 575. | Autharis (poisoned). |

| 591. | Agilulf. |

| 615. | Adaloald. He was poisoned. |

| 625. | Ariold. |

| 636. | Rotharis. He married Ariold's widow, and published a code of laws. |

| 652. | Rodoald (son), assassinated. |

| 653. | Aribert (uncle). |

| 661. | Bertharis and Godebert (sons); dethroned by— |

| 662. | Grimoald, Duke of Beneventum. |

| 671. | Bertharis (re-established). |

| 686. | Cunibert (son). |

| 700. | Luitbert; dethroned by— |

| 701. | Ragimbert. |

| 701. | Aribert II. (son). |

| 712. | Ansprand elected. |

| 712. | Luitprand (son); a great prince, favourite of the Church. |

| 744. | Hildebrand (nephew), deposed. |

| 744. | Ratchis, Duke of Friuli, elected, but afterwards became a monk. |

| 749. | Astolfo (brother). |

| 756. | Desiderius, quarrelled with Pope Adrian, who invited Charlemagne to Italy. He defeated and dethroned Desiderius, and put an end to the Lombard kingdom. |

LONGOBARD MASTERS

| About | |||

| 1. | 712 | Magister Ursus | Sculptured the altar at Ferentilla, and a ciborium at S. Giorgio di Valpolicella, for King Luitprand. |

| 2&3. | 712 | M. Ivvintino and Ivviano. (Joventino and Joviano) | Disciples of Ursus. |

| 4. | " | Magister Giovanni | Made the tomb of S. Cumianus. |

| 5. | 739 | M. Rodpert | Worked at Toscanella, and bought land there. |

| 6. | 742 | M. Piccone | Architect employed by Gunduald at Lucca: he received a gift of lands in Sabine in 742. |

| 7. | M. Auripert | A painter patronized by King Astolph. |

It was on April 2, 568, that the Longobards under Alboin, with their wives and children and with all their belongings, "colle loro mogli e figli, e con tutte le sostanze loro," first came down and took Friuli. Alboin gave the government there to Gisulph, his nephew, leaving with him many of the chief and bravest families, and a high-bred race of horses (generosa razza di cavalli).

Next he took Vicenza and Verona, and in September 569 passed into Liguria—which then extended from the 32 Adda to the Ligurian Sea,—and conquered Milan. To this add Emilia, and later, Ravenna and Tuscany, and the first Lombard kingdom was complete.

From this kingdom depended the three dukedoms of Friuli, Spoleto, and Beneventum. The last was added in the time of Autharis (575-591) when, like Canute, he rode into the sea at Reggio in Calabria, and touching the waves with his lance, cried—"These alone shall be the boundary of the Longobards."[20]

This Autharis married Theodolinda, a Christian. He was an Arian, but by her means he became Catholic. After his death, in 590, she chose Agilulf, who reigned with her twenty-five years.[21]

Paulus Diaconus gives the following very pretty account of Theodolinda's two betrothals—

"It was expedient for Autharis, the young King of the Lombards, to take a wife, and an ambassador was sent to Garibald, King of Bavaria, to propose an alliance with his daughter Theodolinda. Autharis disguised himself as one of the suite, with the object of seeing beforehand what his bride was like. She was sent for by her father and bidden to hand some wine to the guests. Having served the ambassador first, she handed the cup to Autharis, and in giving him the serviette after drinking, he managed to press her hand. The princess blushed, and told the incident to her nurse, who in a prophetic manner assured her that he must be the king himself, or he would not have dared to touch her.

"Soon after, on the Franks invading Bavaria, Theodolinda with her brother fled to Italy, where Autharis met her near Verona, and the marriage was solemnized on the Ides of May, A.D. 589.

"Amongst the guests were Agilulf, Duke of Turin, and with him a youth of his suite, son of an augur; in a sudden storm a tree near them was struck by lightning, on which the young augur said to Agilulf—'The bride who has arrived to-day will shortly wed you.' Agilulf was so angry at what seemed a disrespect to the king and queen, that he threatened to cut off his page's head, who replied—'I may die, but I cannot change destiny.' And truly, when a few years after Autharis was poisoned at Pavia, Theodolinda's people were so attached to her, that they offered her the kingdom if she would elect a Longobard as husband.

"Destiny had decreed that she should choose Agilulf. The same ceremony of offering him a cup of wine was gone through, and he kissed her hand as she gave it. The queen blushing said—'He who has a right to the mouth need not kiss the hand.' So Agilulf knew that he was her chosen king.

"She was a Christian, and a favourite disciple of Gregory the Great. Her good life and prayers were able to convert Agilulf to orthodox Christianity, for like many Longobards of the time he had fallen into the Arian heresy. In gratitude for this she vowed a church to St. John Baptist, and a miraculous voice inspired her as to the site at Modœcia, or 'oppidum moguntiaci.'"

It was under these Christianized invaders that the Comacine Masters became active and influential builders again, and it is here that the actual history of the guild begins.

It is apparent that what are called Lombard buildings could not have been the work of the Longobards themselves. Symonds realized this difficulty, but had not solved the question as to who built the Lombard churches, when he wrote[22]—"The question of the genesis of the Lombard style, is one of the most difficult in Italian art history. I would 34 not willingly be understood to speak of Lombard architecture in any sense different from that in which it is usual to speak of Norman. To suppose that either the Lombards or the Normans had a style of their own, prior to their occupation of districts from the monuments of which they learned rudely to use the decayed Roman manner, would be incorrect. Yet it seems impossible to deny that both Normans and Lombards, in adapting antecedent models, added something of their own, specific to themselves as northerners. The Lombard, like the Norman, or the Rhenish Romanesque, is the first stage in the progressive mediæval architecture of its own district."

It appears possible, however, that the Longobards had very little to do with the architecture of their era except as patrons. Was there ever a stone Lombard building known out of Italy before Alboin and his hordes crossed the Alps? or even in Italy during the reigns of Alboin and Cleoph, their first kings?

But there were older buildings of precisely the same style, in Italy and in Como itself, dating from the time when the Bishops ruled, long before the Longobards came. There were the churches of S. Abbondio and S. Fedele. The latter was built in Abbondio's own time, about 440-489, and first dedicated to S. Euphemia. It was rebuilt later by the Comacines under the Longobards, but its form was not changed. The former, said to have been built by the Bishop Amantius, was first dedicated to SS. Peter and Paul, whose relics he placed here. These two are certainly the oldest churches existing in Como.

Amantius the Byzantine ordained S. Abbondio, who was a Macedonian, as his successor, and he too became eminent in his time, and is still venerated as a patron Saint in all the Milanese district. Pope Leo sent him to Constantinople as his Legate, to interview the Patriarch Anastasius, and also deputed him to form the Council with 35 Eusebius, at Milan. The Greek touch in the Lombard ornamentation may be accounted for by Greek sculptors assisting the Italian builders in the time of these Eastern bishops.

But, to return to the Longobards:—it was only when the civilization of Italy began to tell on them, and Christianity refined their minds, that they commenced to patronize the Arts, and revived the fading traditions of the builders' guild into practice, for the glorification of their religious zeal. "Little by little," says Muratori, "the barbarous Longobards became more polished (andavano disrugginendo) by taking the customs and rites of the Italians. Many of them were converted from Arianism to Catholicism, and they vied with the Italians in piety and liberality towards the Church of God, building both Hospices and Monasteries."[23]

The Comacine Masters were undoubtedly the only architects employed by them, so we are sure that in the Lombard churches of this era, we see the Comacine work of the first or Roman-Lombard style.

Autharis and Theodolinda were the first orthodox Christians: indeed Theodolinda, who was baptized by Gregory the Great, and formed a special friendship with him, became a shining light in the Church. To them is probably due the honour of inaugurating the Renaissance of Comacine art. Autharis, though an Arian, first employed the Masters of the guild to build a church and monastery at Farfa on the banks of the Adda, not far from Monza. They have long been ruined, but ancient writers quote them as fine and rich works of architecture. Next, Theodolinda and her second husband, Agilulf, the succeeding king, built the cathedral at Monza, which they resolved should be worthy of the new creed. This cathedral was the prototype of all the Lombard churches.

Before proceeding further it may be well to define precisely the difference between Eastern and Western forms in these centuries, while they were as yet distinct.

As we have said, the Basilica was the type of Roman or Western architecture, a type which passed afterwards to the East, where the cupola was added to it.

The Comacine Guild, being a survival of the Roman Collegium, had of course Roman traditions, and took naturally this Roman type of the Basilica,[24] which form they adapted to the uses of the Christian Church, while its ornamentation was suited to the taste of the Longobards.

The Basilica, as Vitruvius explains it, was a room where the ruler and his delegates administered justice. But when, after the persecutions, Christians were allowed their churches, the Basilicæ so well supplied the needs of Christian worship, that either the ancient ones were used as churches, or new buildings were erected in the same form; so that by the fourth century the word Basilica was understood to mean a church remarkable for its size, and of a set form and grandeur, with a raised tribune. The Basilicæ of Constantine were all dedicated to Saints—St. Peter, St. Paul, Beato Marcellino. The Sessorian Basilica was begun in 330, to hold the relics of the Cross, discovered by the Empress Helena. From the time of the edict of Theodosius, however, Christian architecture took a new and independent character; and this was when the Basilica became amplified and beautified.

The Oriental churches, on the other hand, were derived from the antique synagogue, in which concentric forms, 37 either circular or polygonal, predominated. In their later development four equal arms were added, and here we get the Greek Cross, in the centre of which arose the dome.

In the Romanesque, or Comacine style of the ninth to the fourteenth centuries, the form becomes more complicated. We have, 1. the sanctuary or presbytery; 2. the apse for the choir; 3. the transepts; 4. the normal square or centre; 5. the elongated nave; 6. the aisles; 7. the atrium or portico.

In Theodolinda's time, however, church architecture in Lombardy was wholly and purely Roman, with the influences of mediæval Christianity. Ricci tells us that the construction of the first churches followed a symbolical expression. "Hermeneutic symbolism required that the apse or choir should face the east, so that the faithful while praying had that part before them."

A very usual form was the tri-apsidal church, of which many specimens still exist. S. Pietro a Grado, near Pisa, is a beautiful specimen of this.

Around the apse of a Lombard church was a portico where the penitents and catechumens might stand, who were not yet admitted to the altar. On high were loggie (galleries) "for the virgins and women." The tribune was elevated and often ornamented with a railing, the crypt or confessional being beneath it. The crypt signified a memory of the early Christians, when subterranean catacombs formed the church of the faithful. The altar was generally the tomb of a martyr, in fulfilment of the text—"I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God, and for the testimony which they held" (Rev. vi. 9).

Where the original form of the Lombard church has not been altered, as in the first Monza church, all these parts may be still seen. 38

We are expressly told by Ricci,[25] that for the building of her church at Monza, Queen Theodolinda availed herself of those Magistri Comacini, who, as Rotharis describes them in his laws 143 and 144, were qualified architects and builders.

It seems that even though all Italy was subjugated by the Longobards, the Magistri Comacini retained their freedom and privileges. They became Longobard citizens, but were not serfs; they retained their power of making free contracts, and receiving a fair price for their work, and were even entitled to hold and dispose of landed property.[26]

Therefore it was by a free contract, and not in any spirit of servitude, that the Comacines undertook the building of Theodolinda's church.

It is difficult to imagine what the church was in Theodolinda's time, as its form was altered in the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. Ricci says that the antique Monza Basilica terminated at what is now the first octagon column, on which rest the remains of the primitive façade. Four columns supported the arched tribune, and the high altar was raised above the level of the church. In front was the atrium, supported by porticoes, and he thinks that the sculptures in the present façade are the old ones.

Cattaneo, the Italian authority on Lombard architecture, does not believe in the present existence of even this much of Theodolinda's church, and in disclaiming the façade, disclaims also the sculpture on it, especially the one over the door, where Agilulf and Theodolinda offer the diadem of the cross to St. John the Baptist, and are shown as 39 wearing crowns, which the early Lombard kings did not do.[27] The figures have, it is true, the entire style of the twelfth century, when later Comacines restored the church. Cattaneo thinks that the only sculpture which can safely be dated from Theodolinda's own time, is a stone which might have been an altar frontal, on which is a rude relief of a wheel circle, emblem of Eternity, flanked by two crosses with the letters alpha and omega hanging to the arms of them. It is a significant fact that the Alpha is in the precise form of the Freemason symbol of the compasses, and in the wheel-like circle one sees the beginning of that symbol of Eternity, the unbroken line with neither end nor beginning, which the Comacines in after centuries developed into such wonderful intrecci (interlaced work). The sculpture is extremely rude; by way of enriching the relief, the artist has covered the crosses and circles with drill-holes. Now this is a most interesting link, connecting the debased Roman art with this beginning of the Christian art in the West (the early Ravenna sculptors do not count, being imported from the East). On examining any of the late Roman cameos, or intagli, or even their stone sculpture, after the fall of classical art in Hadrian's time, one may perceive the way in which the drill is constantly made use of instead of the chisel.

So these Comacine artists began with the only style of art they had been educated up to, and though retaining old traditions they had fallen out of practice, during a century or two, while invaders ravaged their country, and had to begin again with low art, little skill, and unused imagination. But with the new impulse given to art, their skill increased, they gained a wider range of imagination, greater breadth of design, going on century by century, as we shall trace, from the first solid, heavy, little structures, to 40 the airy lightness of the florid Romanesque—the marriage of East and West.

Another chiesa graziosissima, said to have been founded by Theodolinda, was that of Santa Maria del Tiglio, near Gravedona, on the left bank of Lake Como, which Muratori says was already ancient in 823, when the old chronicler Aimoninus describes it (Aimoninus de Gestis Francorum, iv. 3). It has been much altered since that time, but as Prof. Merzario writes—"When one reflects that it was the work of a thousand years ago, and when one considers the lightness of design, the elegance of the arches, windows, columns, and colonnettes, one must perforce confess that even at that epoch Art was blossoming in the territory of Como, under the hands of the Maestri Comacini."

Theodolinda also founded the monastery of Monte Barro, near Galbiate; the church of S. Salvatore in Barzano, a little mountain church at Besano above Viggiu; that of S. Martino at Varenna; and the church, baptistery, and castle of Perleda above it; in which latter it is said she died. Queen Theodolinda was accustomed to spend the hot months of summer on the banks of the lake, and a part of the road near Perleda Castle is still called Via Regina (the Queen's road), in memory of her. King Cunibert, too, loved the banks of Como.

There is always some pretty, graceful reason in Theodolinda's church-building, very different to the reasons of many of the kings. Theirs were too often sin-offerings, built in remorse, but hers were generally thank-offerings, built in love. For instance, the church at Lomella, which she erected in memory of having first met her second husband Agilulf there.