|

By Justin Winsor. NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL HISTORY OF AMERICA. With Bibliographical and Descriptive Essays on its Historical Sources and Authorities. Profusely illustrated with portraits, maps, facsimiles, etc. Edited by Justin Winsor, Librarian of Harvard University, with the coöperation of a Committee from the Massachusetts Historical Society, and with the aid of other learned Societies. In eight royal 8vo volumes. Each volume, net, $5.50; sheep, net, $6.50; half morocco, net, $7.50. (Sold only by subscription for the entire set.) READER'S HANDBOOK OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION. 16mo, $1.25. WAS SHAKESPEARE SHAPLEIGH? 16mo, rubricated parchment paper, 75 cents. CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS. With portrait and maps. 8vo. HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & COMPANY, Boston and New York |

AND HOW HE RECEIVED AND

IMPARTED THE SPIRIT

OF DISCOVERY

BY

JUSTIN WINSOR

They that go down to the sea in ships,

that do business in great waters, these

see the works of the Lord and his wonders

in the deep.—Psalms, cvii. 23, 24

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1891

To FRANCIS PARKMAN, LL.D.,

The Historian of New France.

Dear Parkman:—

You and I have not followed the maritime peoples of western Europe in planting and defending their flags on the American shores without observing the strange fortunes of the Italians, in that they have provided pioneers for those Atlantic nations without having once secured in the New World a foothold for themselves.

When Venice gave her Cabot to England and Florence bestowed Verrazano upon France, these explorers established the territorial claims of their respective and foster motherlands, leading to those contrasts and conflicts which it has been your fortune to illustrate as no one else has.

When Genoa gave Columbus to Spain and Florence accredited her Vespucius to Portugal, these adjacent powers, whom the Bull of Demarcation would have kept asunder in the new hemisphere, established their rival races in middle and southern America, neighboring as in the Old World; but their contrasts and conflicts have never had so worthy a historian as you have been for those of the north.

The beginnings of their commingled history I have tried to relate in the present work, and I turn naturally to associate in it the name of the brilliant historian of France and England in North America with that of your obliged friend,

Cambridge, June, 1890.

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER I. | |

|

| Sources, and the Gatherers of Them | 1 | |

|

Illustrations: Manuscript of Columbus, 2; the Genoa Custodia, 5; Columbus's Letter to the Bank of St. George, 6; Columbus's Annotations on the Imago Mundi, 8; First Page, Columbus's First Letter, Latin edition (1493), 16; Archivo de Simancas, 24. |

||

| CHAPTER II. | |

|

| Biographers and Portraitists | 30 | |

|

Illustrations: Page of the Giustiniani Psalter, 31; Notes of Ferdinand Columbus on his Books, 42; Las Casas, 48; Roselly de Lorgues, 53; St. Christopher, a Vignette on La Cosa's Map (1500), 62; Earliest Engraved Likeness of Columbus in Jovius, 63; the Florence Columbus, 65; the Yañez Columbus, 66; a Reproduction of the Capriolo Cut of Columbus, 67; De Bry's Engraving of Columbus, 68; the Bust on the Tomb at Havana, 69. |

||

| CHAPTER III. | |

|

| The Ancestry and Home of Columbus | 71 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

|

| The Uncertainties of the Early Life of Columbus | 79 | |

|

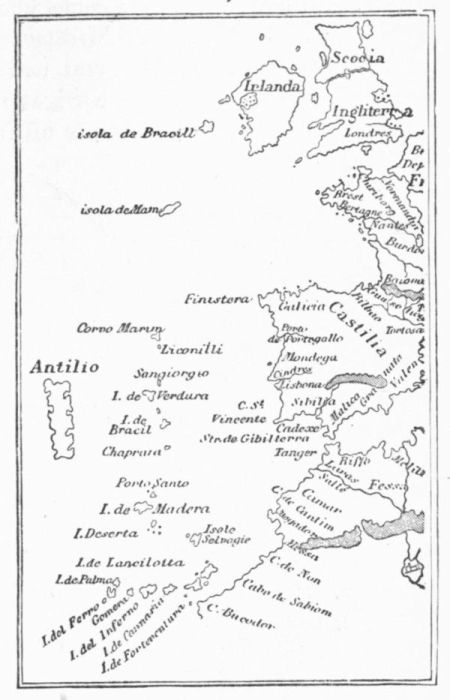

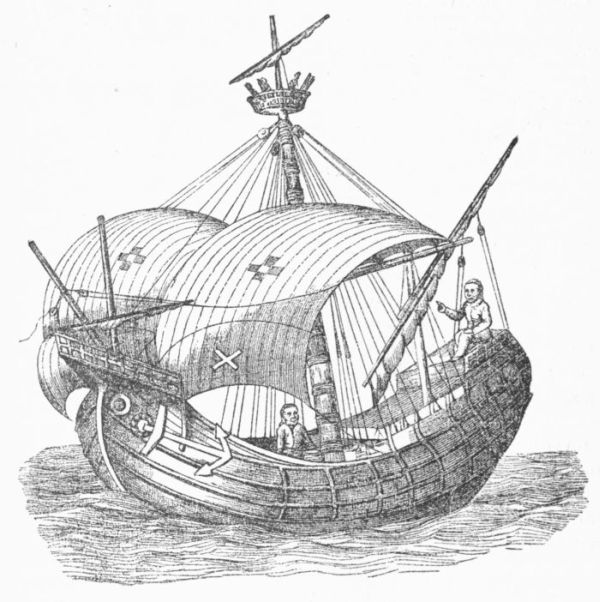

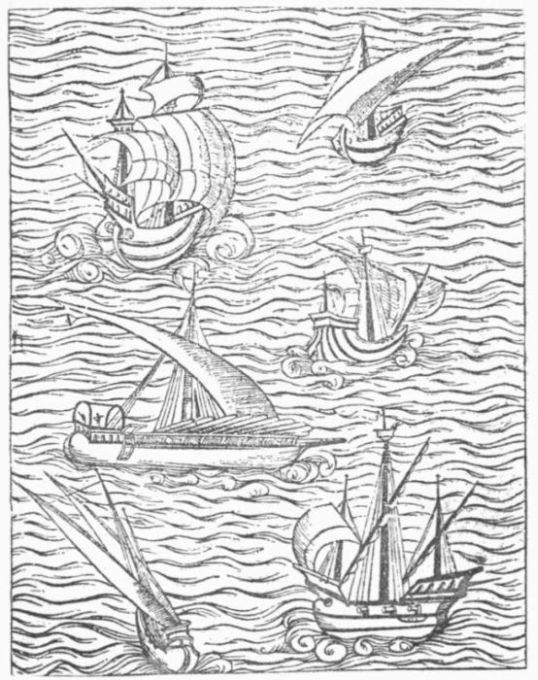

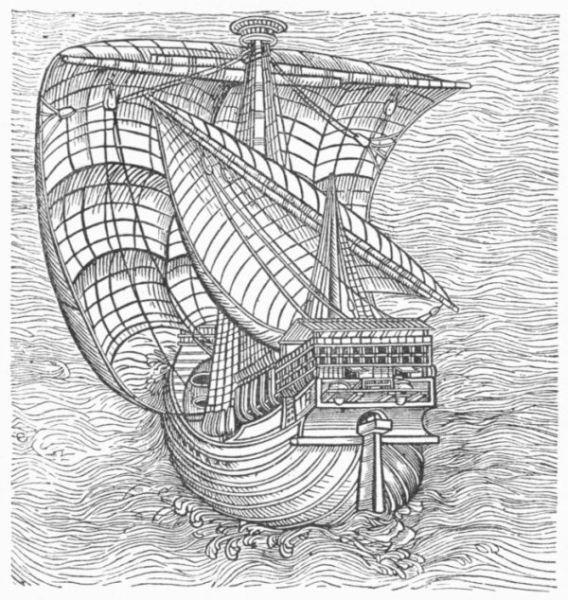

Illustrations: Drawing ascribed to Columbus, 80; Benincasa's Map (1476), 81; Ship of the Fifteenth Century, 82. |

||

| CHAPTER V. | |

|

| The Allurements of Portugal | 85 | |

|

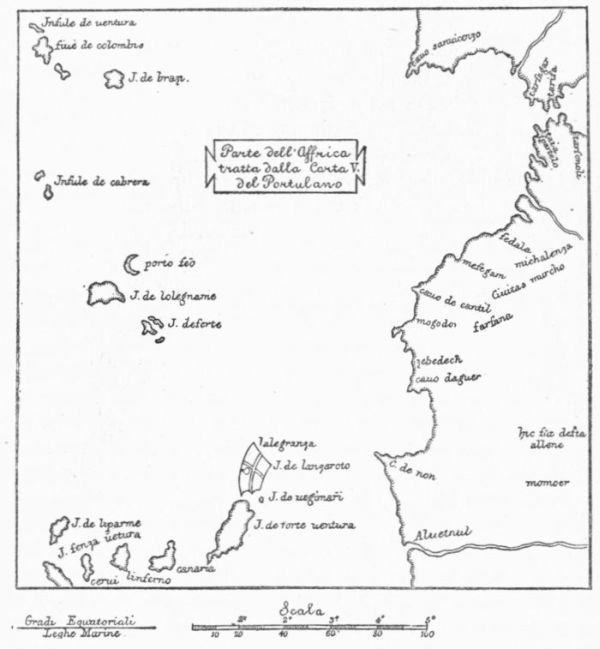

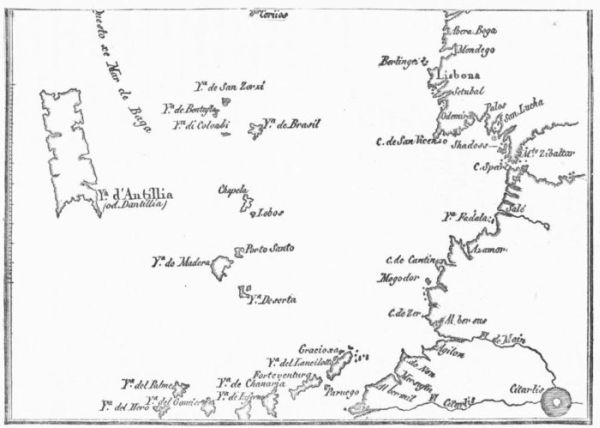

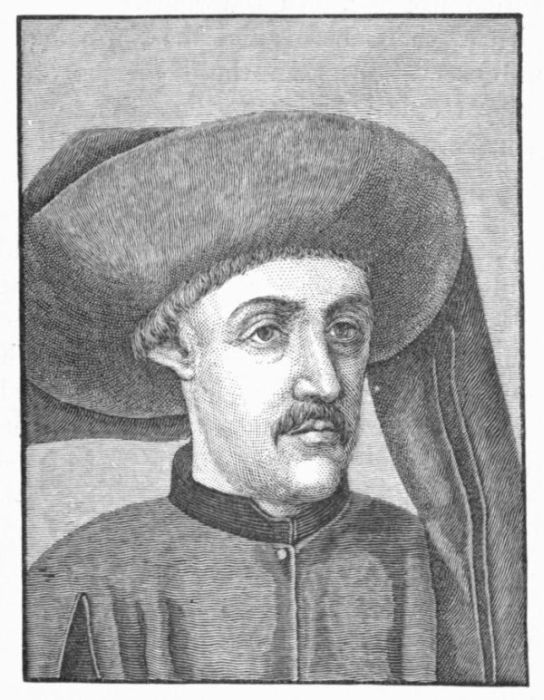

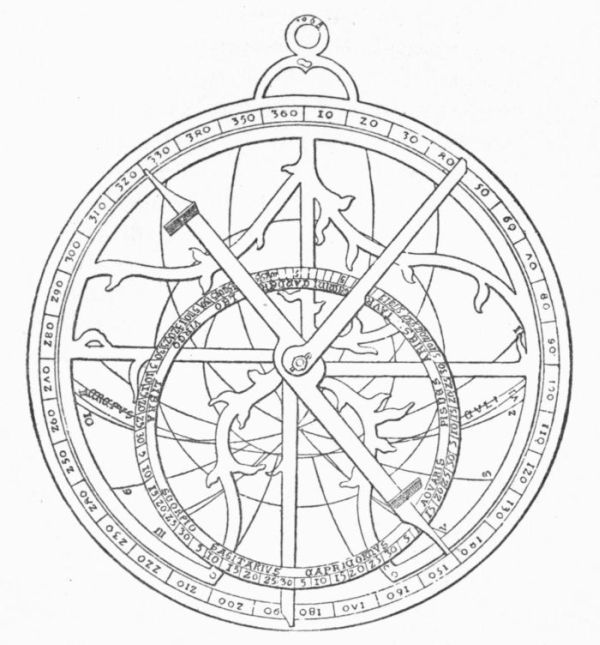

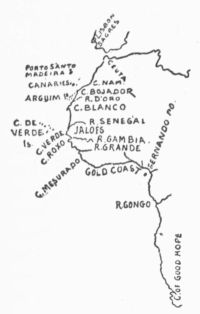

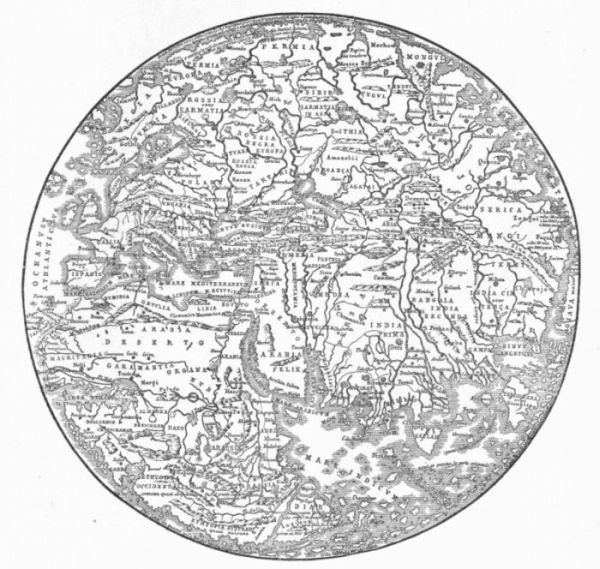

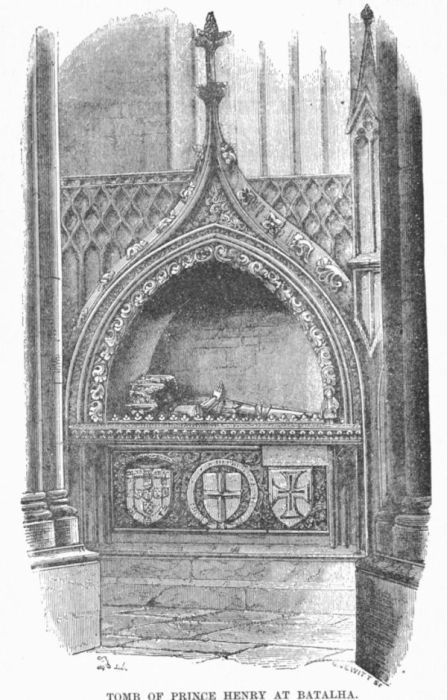

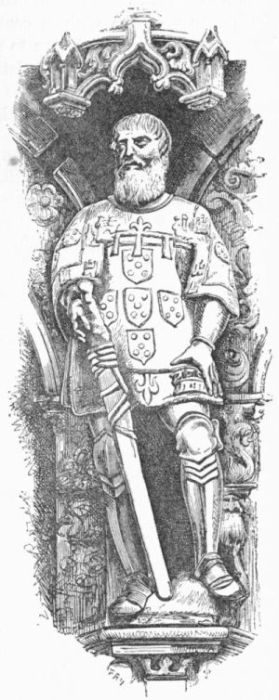

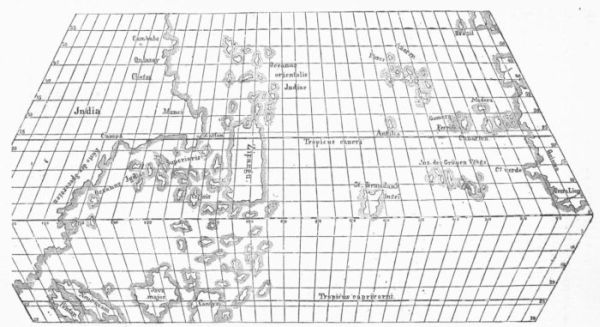

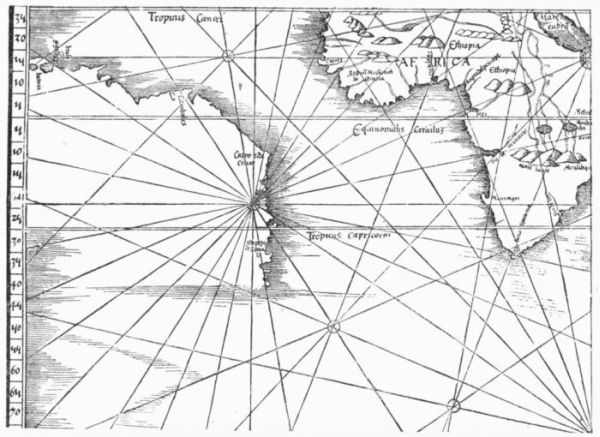

Illustrations: Part of the Laurentian Portolano, 87; Map of Andrea Bianco, 89; Prince Henry, the Navigator, 93; Astrolabes of Regiomontanus, 95, 96; Sketch Map of African Discovery, 98; Fra Mauro's World-Map, 99; Tomb of Prince Henry at Batalha, 100; Statue of Prince Henry at Belem, 101. |

||

| [Pg viii] CHAPTER VI. | |

|

| Columbus in Portugal | 103 | |

|

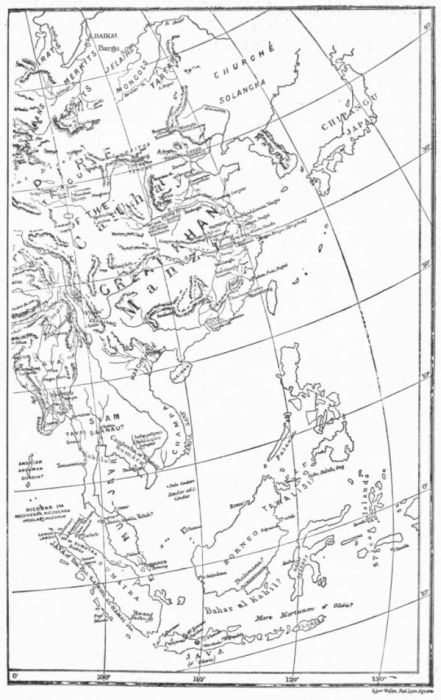

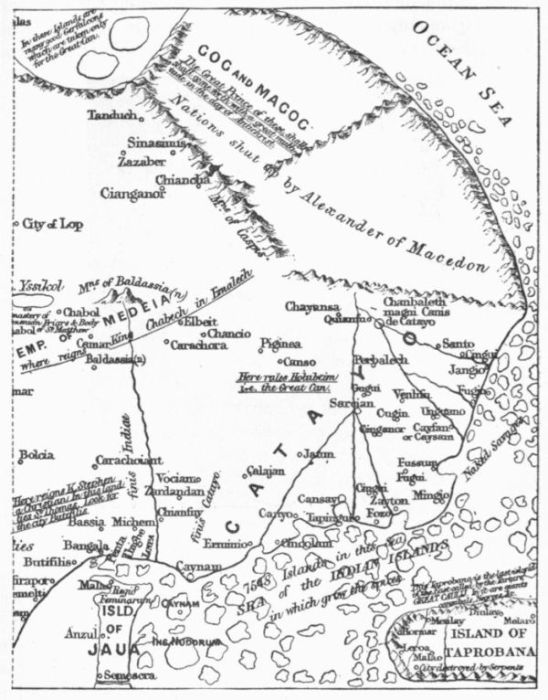

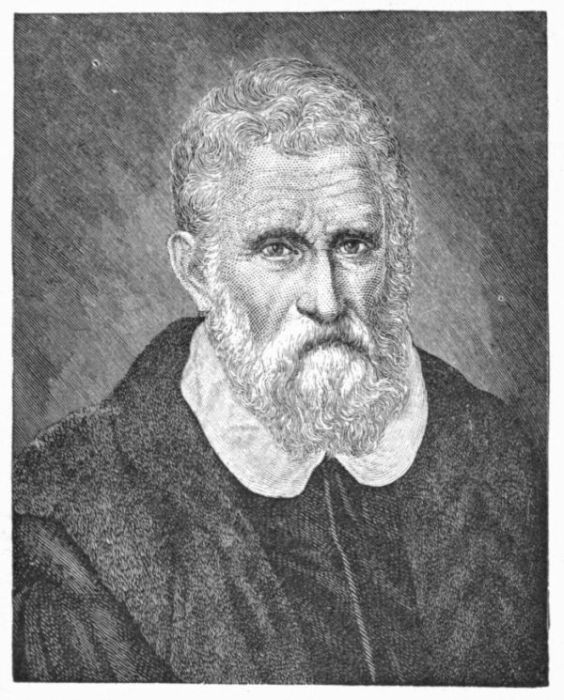

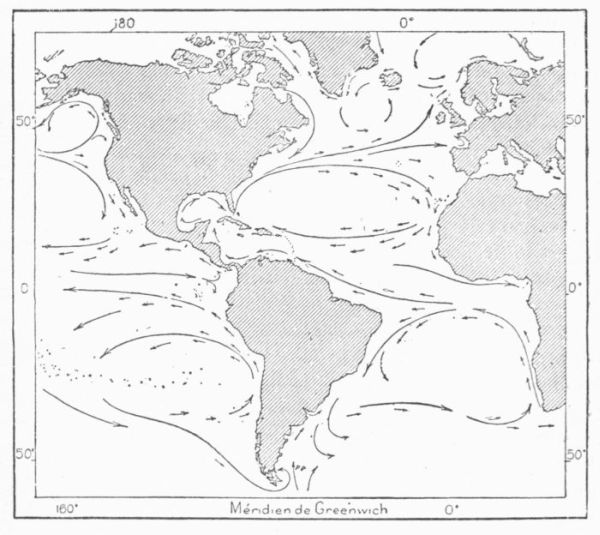

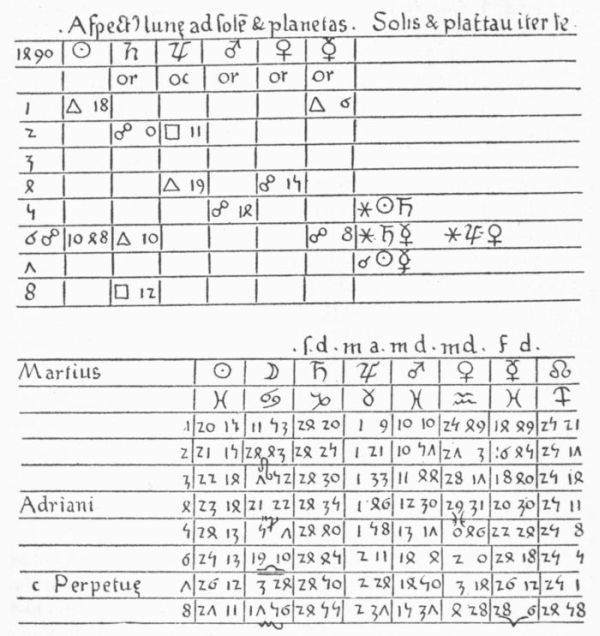

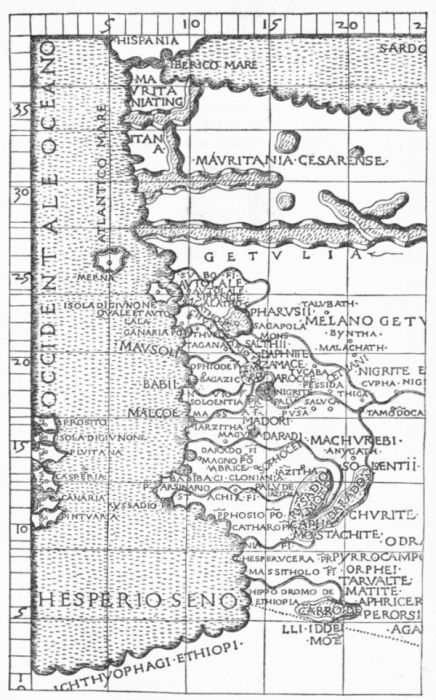

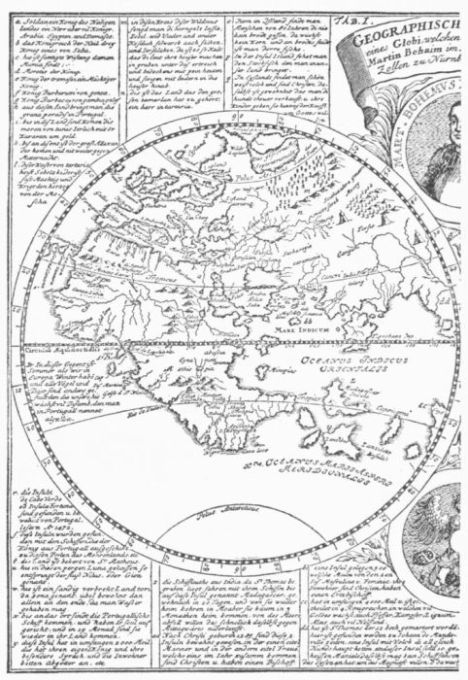

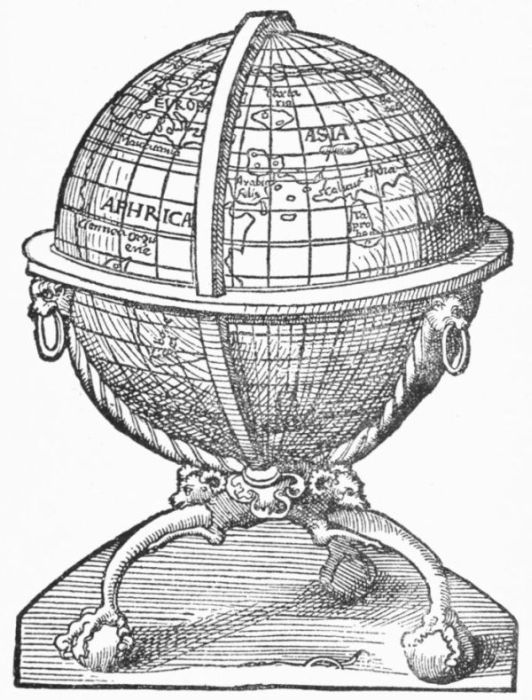

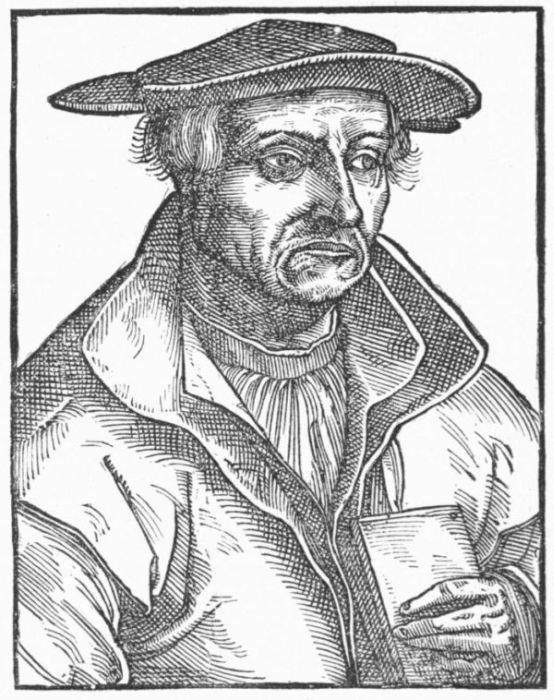

Illustrations: Toscanelli's Map restored, 110; Map of Eastern Asia, with Old and New Names, 113; Catalan Map of Eastern Asia (1375), 114; Marco Polo, 115; Albertus Magnus, 120; the Laon Globe, 123; Oceanic Currents, 130; Tables of Regiomontanus (1474-1506), 132; Map of the African Coast (1478), 133; Martin Behaim, 134. |

||

| CHAPTER VII. | |

|

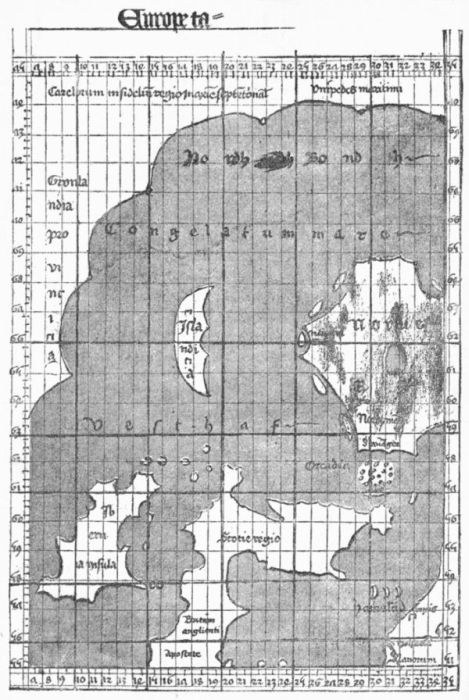

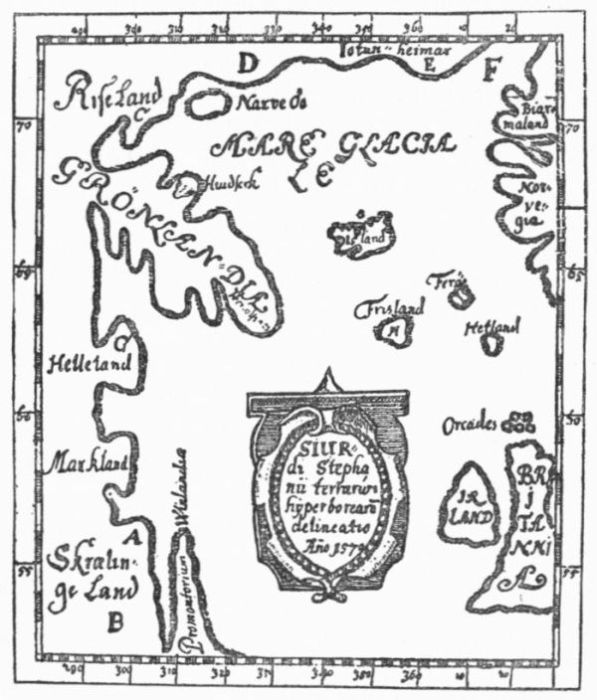

| Was Columbus in the North? | 135 | |

|

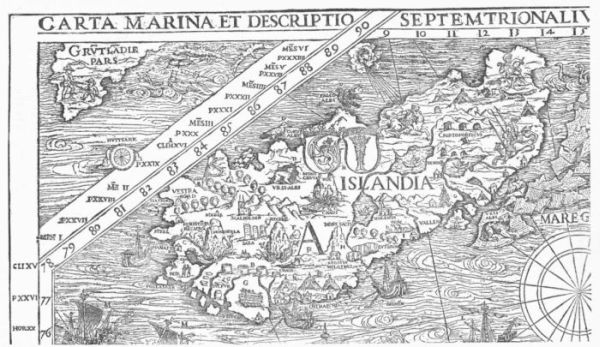

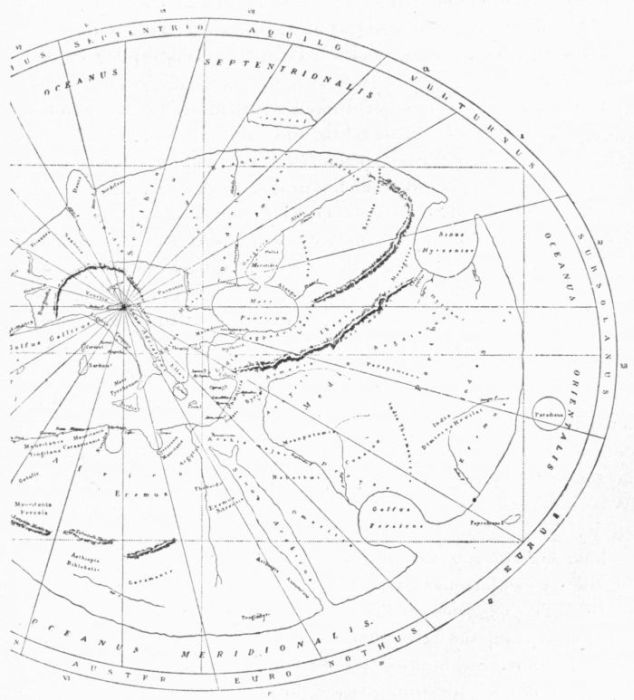

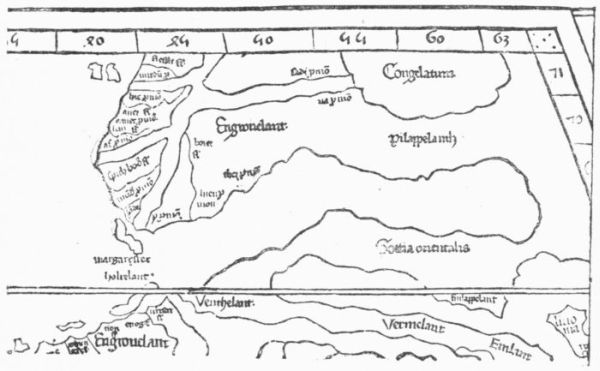

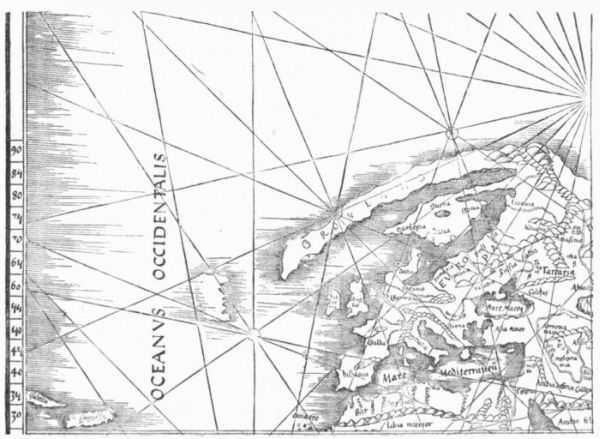

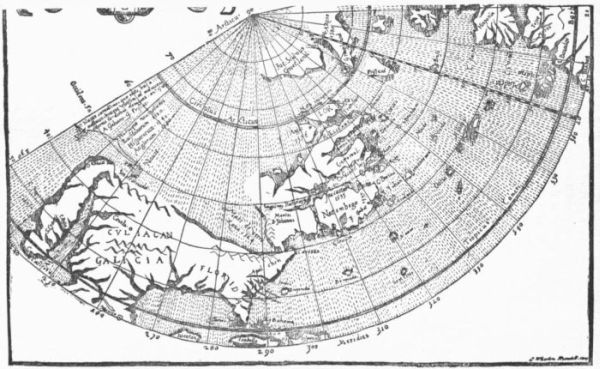

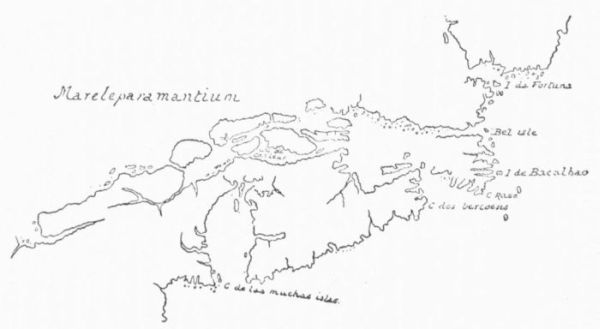

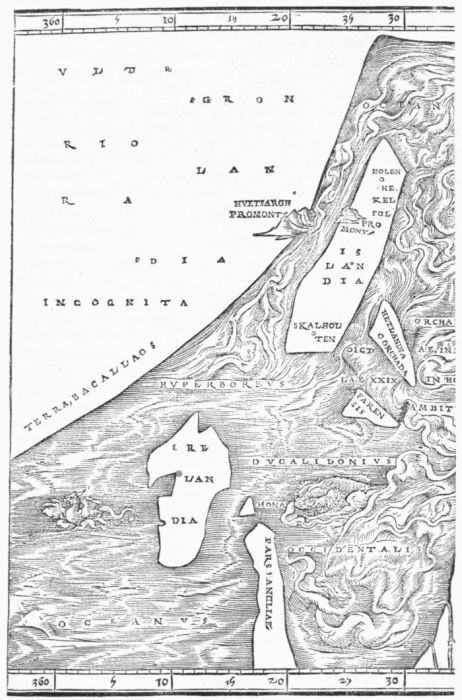

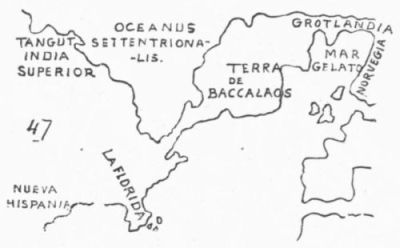

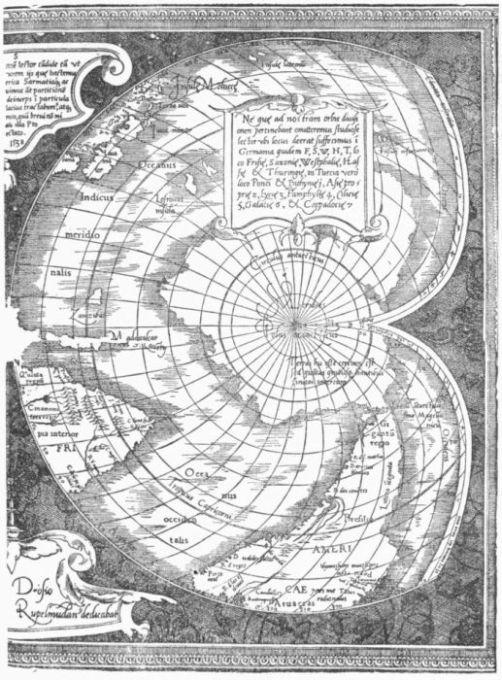

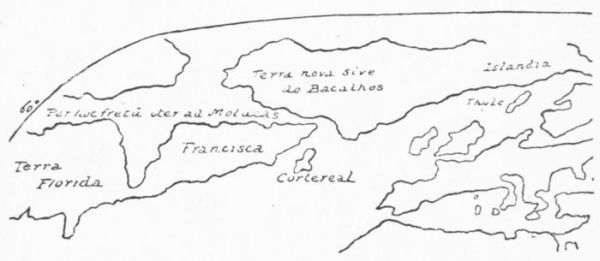

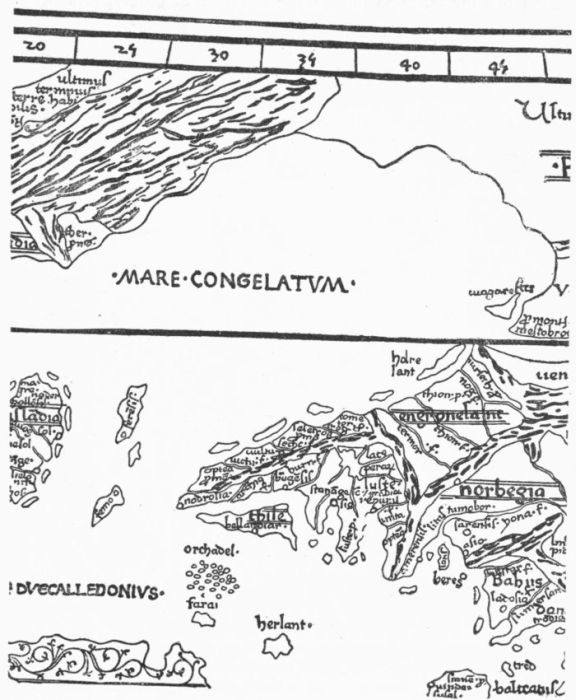

Illustrations: Map of Olaus Magnus (1539), 136; Map of Claudius Clavus (1427), 141; Bordone's Map (1528), 142; Map of Sigurd Stephanus (1570), 145. |

||

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

|

| Columbus Leaves Portugal for Spain | 149 | |

|

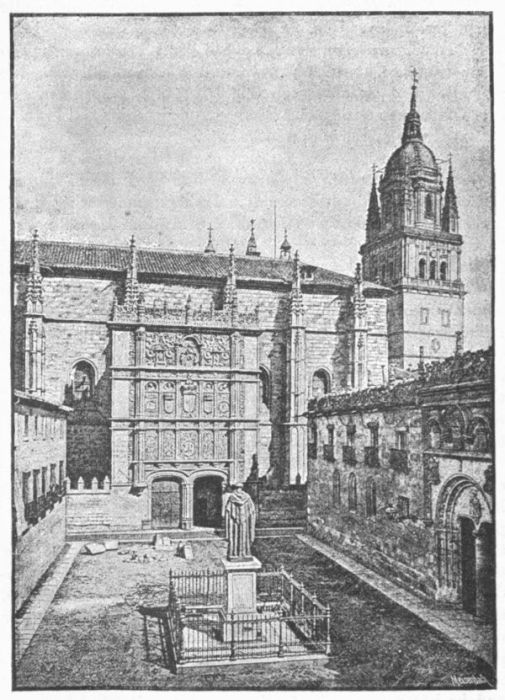

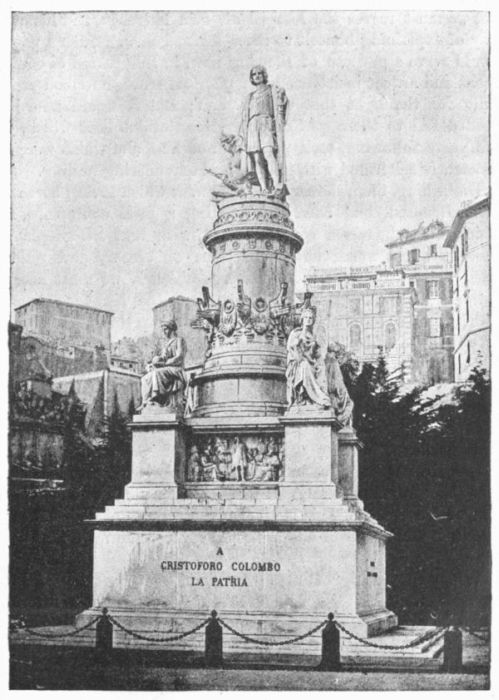

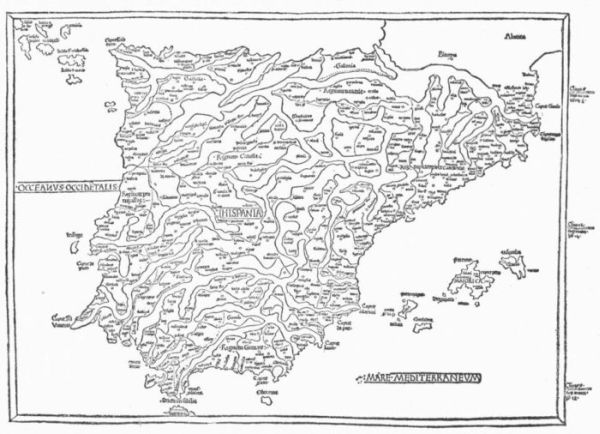

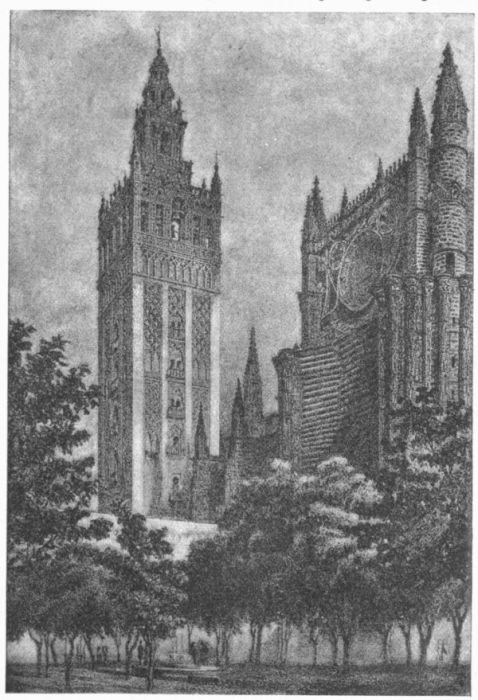

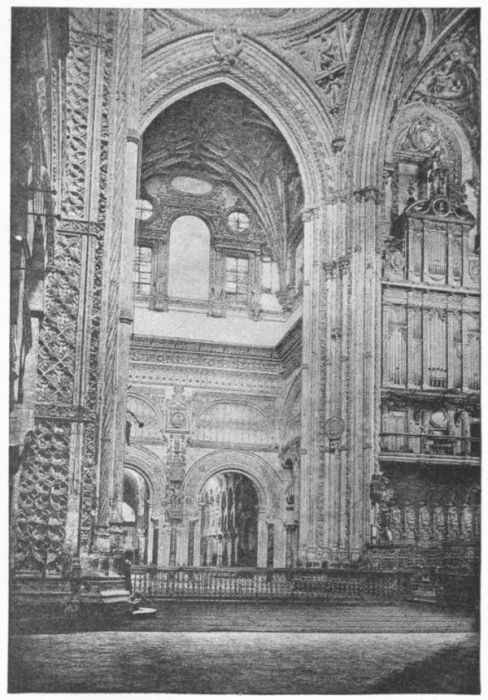

Illustrations: Portuguese Mappemonde (1490), 152; Père Juan Perez de Marchena, 155; University of Salamanca, 162; Monument to Columbus at Genoa, 163; Ptolemy's Map of Spain (1482), 165; Cathedral of Seville, 171; Cathedral of Cordoba, 172. |

||

| CHAPTER IX. | |

|

| The Final Agreement and the First Voyage, 1492 | 178 | |

|

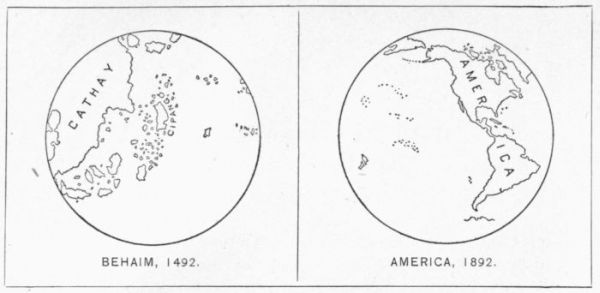

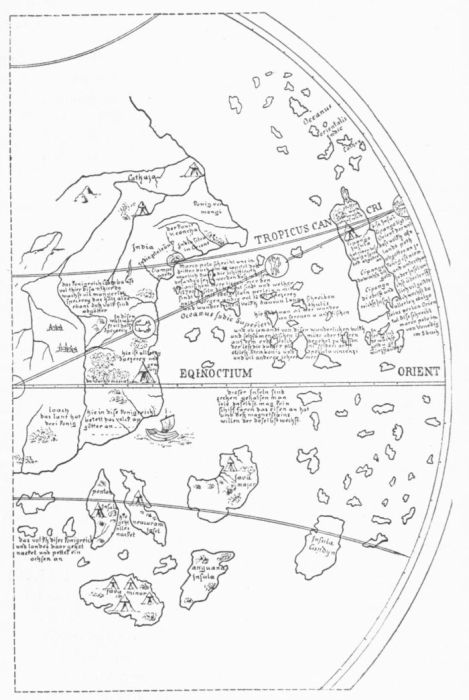

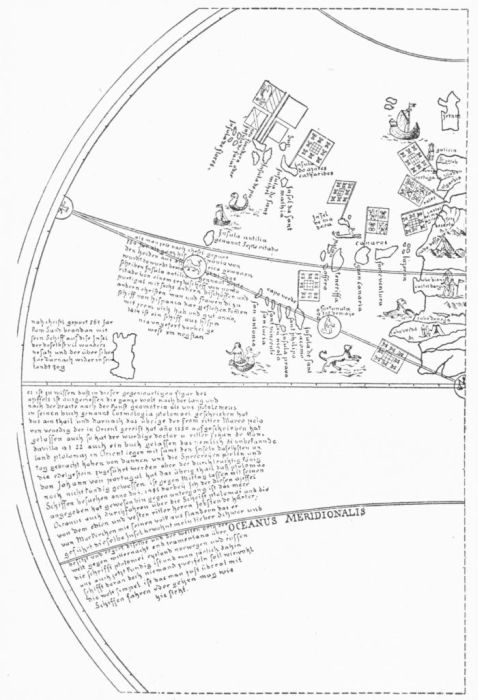

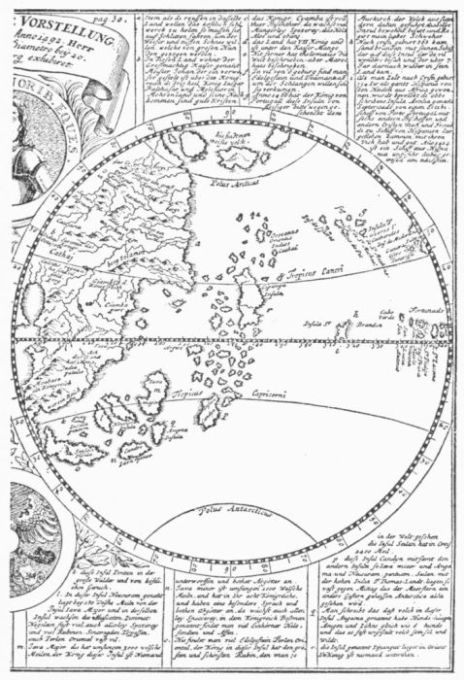

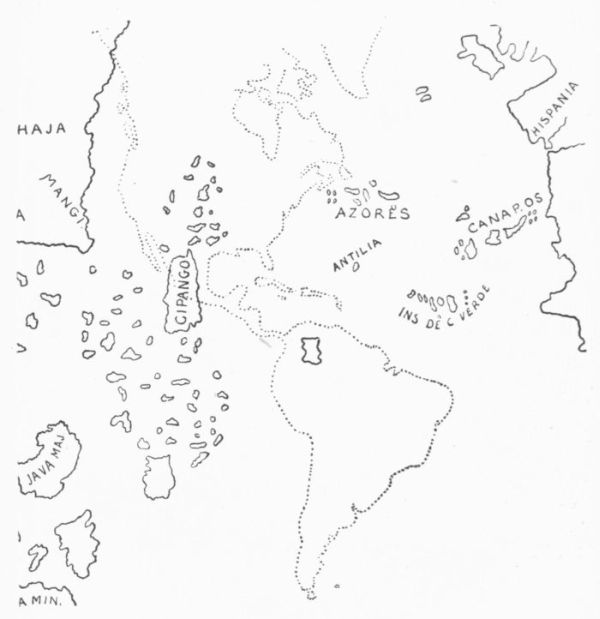

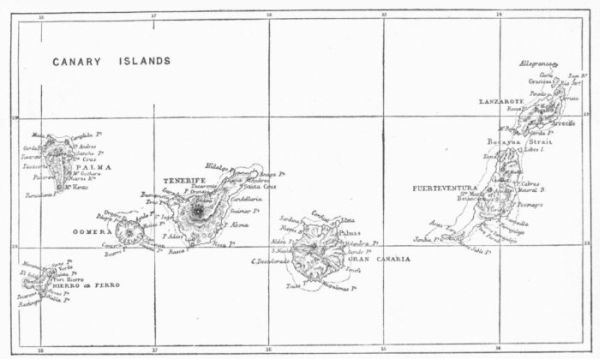

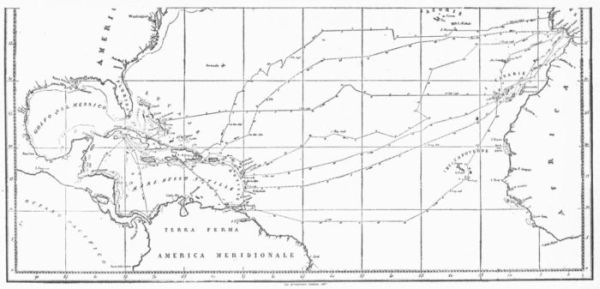

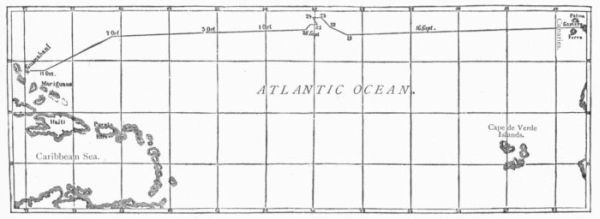

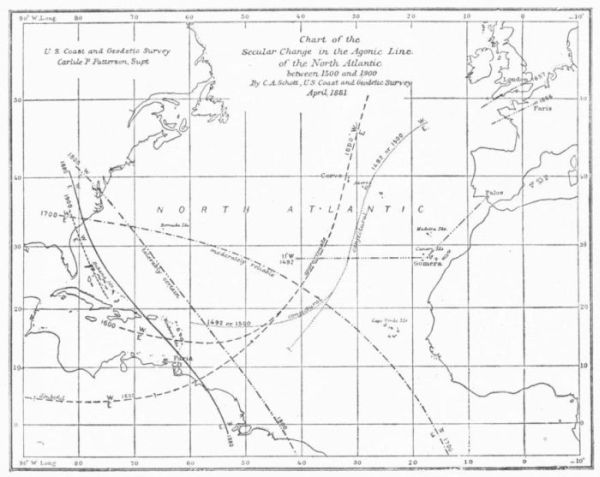

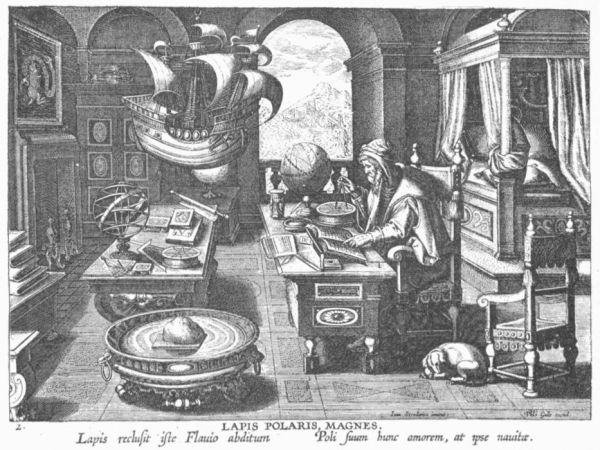

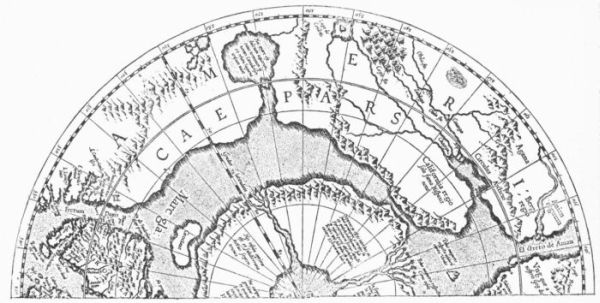

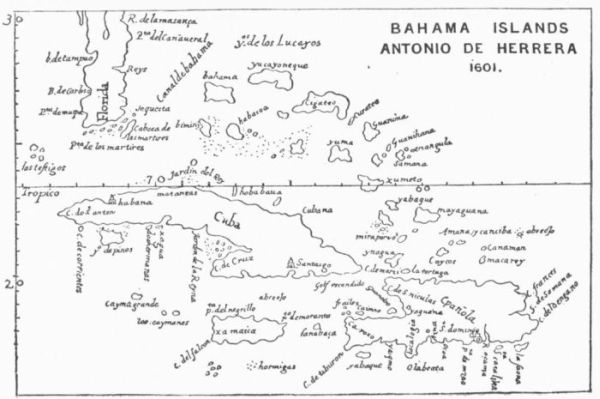

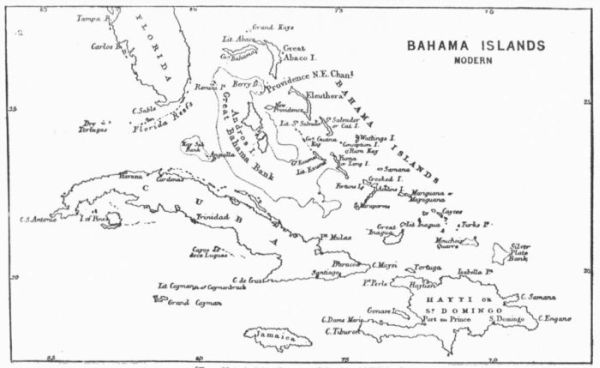

Illustrations: Behaim's Globe (1492), 186, 187; Doppelmayer's Reproduction of this Globe, 188, 189; the actual America in Relation to Behaim's Geography, 190; Ships of Columbus's Time, 192, 193; Map of the Canary Islands, 194; Map of the Routes of Columbus, 196; of his track in 1492, 197; Map of the Agonic Line, 199; Lapis Polaris Magnes, 200; Map of Polar Regions by Mercator (1509), 202; Map of the Landfall of Columbus, 210; Columbus's Armor, 211; Maps of the Bahamas (1601 and modern), 212, 213. |

||

| CHAPTER X. | |

|

| Among the Islands and the Return Voyage | 218 | |

|

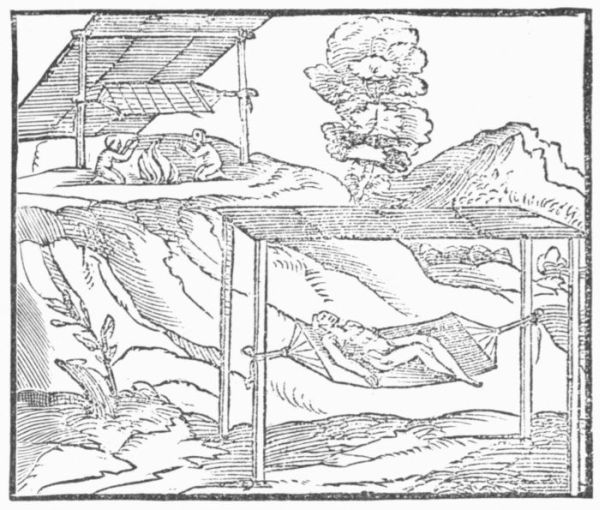

Illustration: Indian Beds, 222. |

||

| [Pg ix] CHAPTER XI. | |

|

| Columbus in Spain again; March To September, 1493 | 243 | |

|

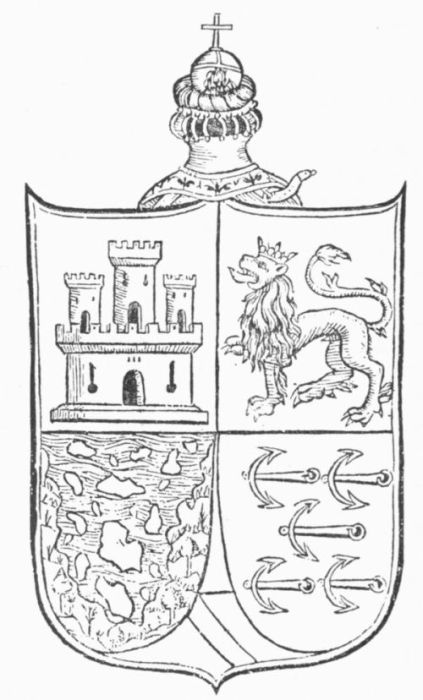

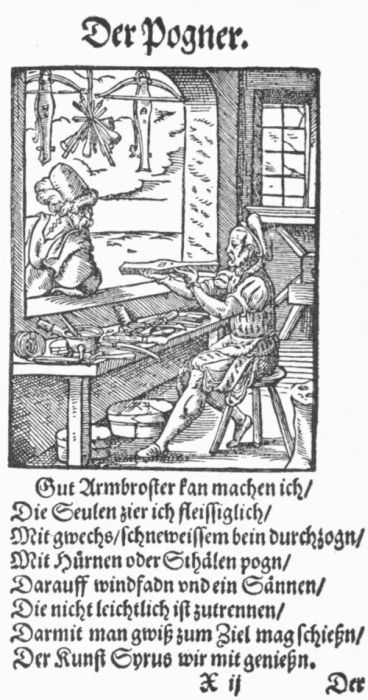

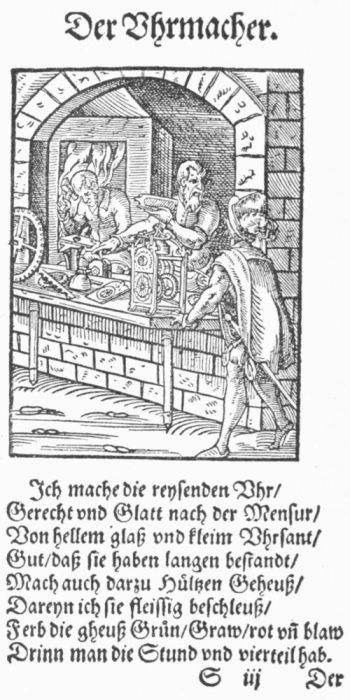

Illustrations: The Arms of Columbus, 250; Pope Alexander VI., 253; Crossbow-Maker, 258; Clock-Maker, 260. |

||

| CHAPTER XII. | |

|

| The Second Voyage, 1493-1494 | 264 | |

|

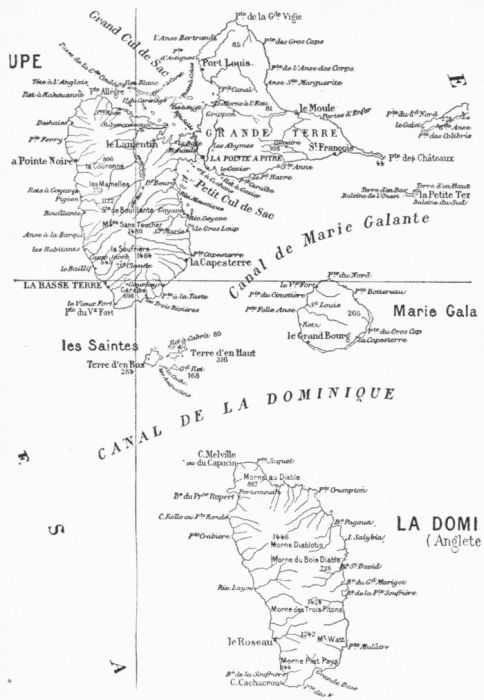

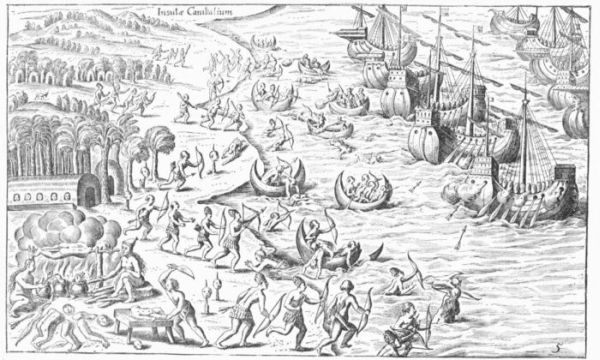

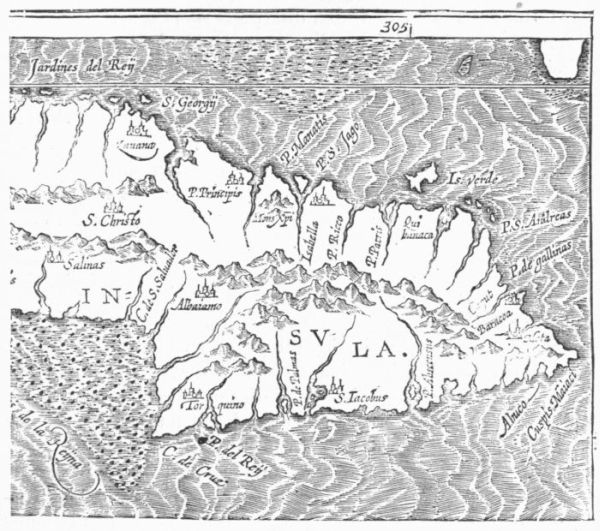

Illustrations: Map of Guadaloupe, Marie Galante, and Dominica, 267; Cannibal Islands, 269. |

||

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

|

| The Second Voyage, continued, 1494 | 284 | |

|

Illustrations: Mass on Shore, 298. |

||

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

|

| The Second Voyage, continued, 1494-1496 | 303 | |

|

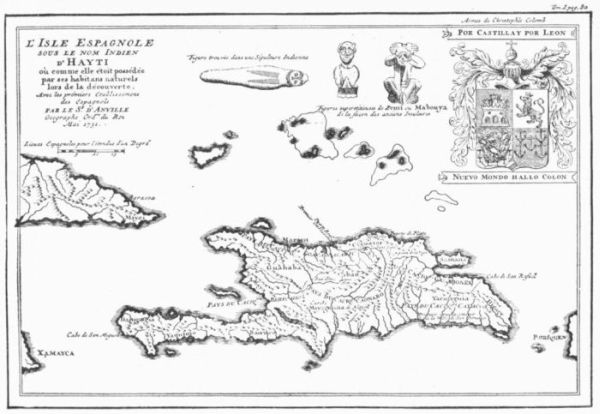

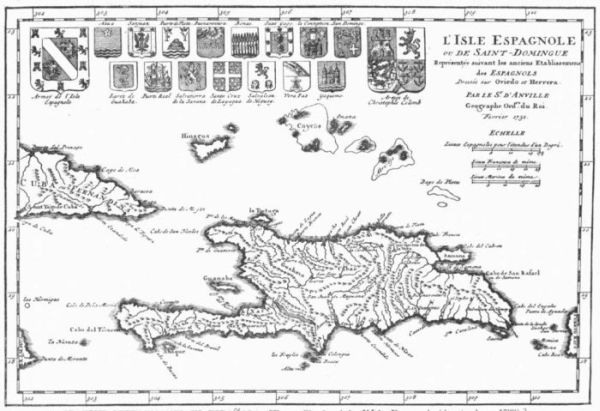

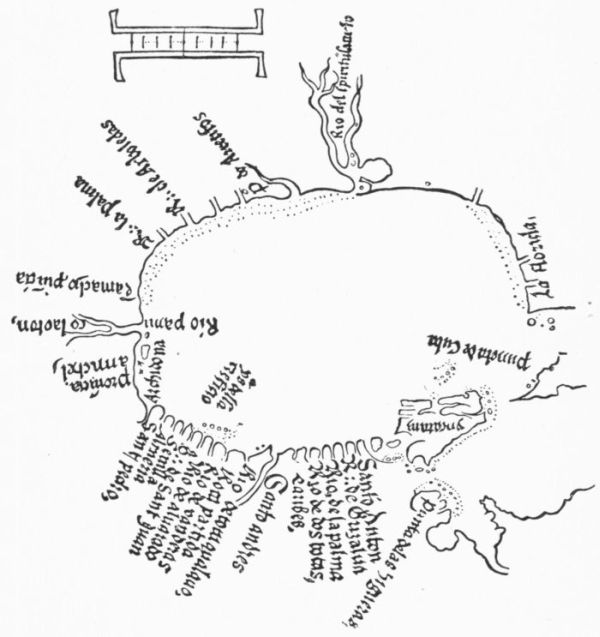

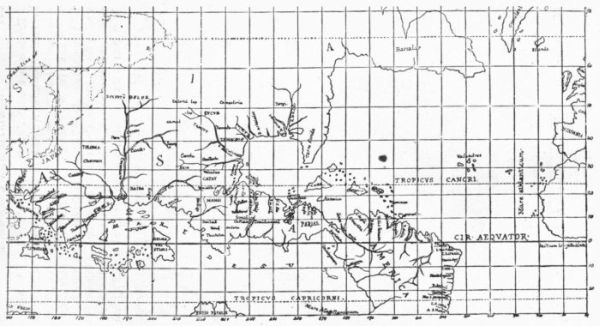

Illustrations: Map of the Native Divisions of Española, 306; Map of Spanish Settlements in Española, 321. |

||

| CHAPTER XV. | |

|

| In Spain, 1496-1498. Da Gama, Vespucius, Cabot | 325 | |

|

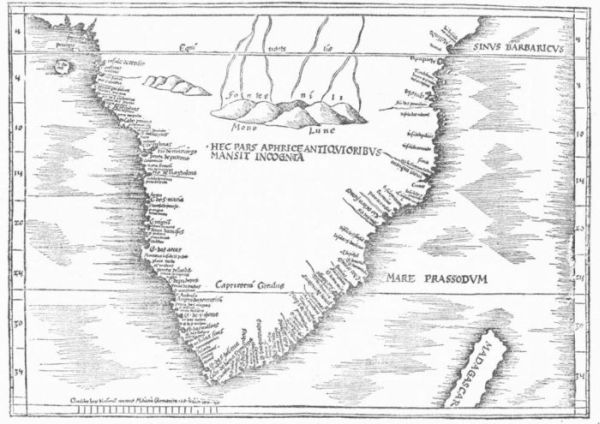

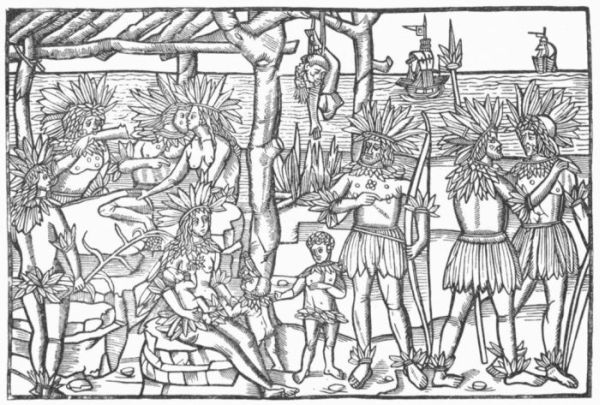

Illustrations: Ferdinand of Aragon, 328; Bartholomew Columbus, 329; Vasco Da Gama, 334; Map of South Africa 1513), 335; Earliest Representation of South American Natives, 336. |

||

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

|

| The Third Voyage, 1498-1500 | 347 | |

|

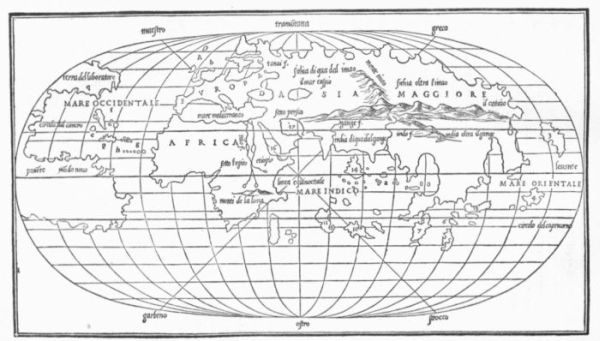

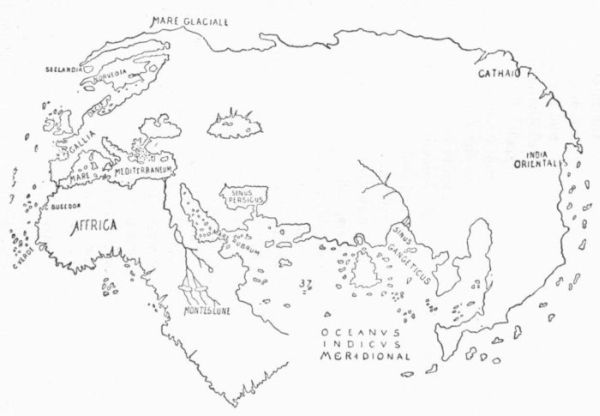

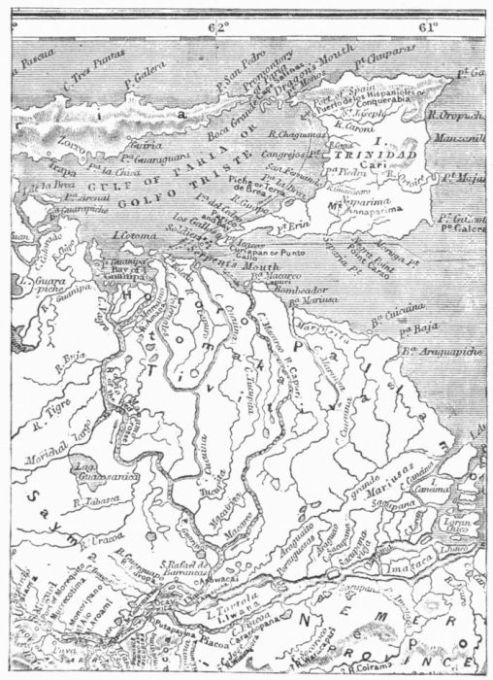

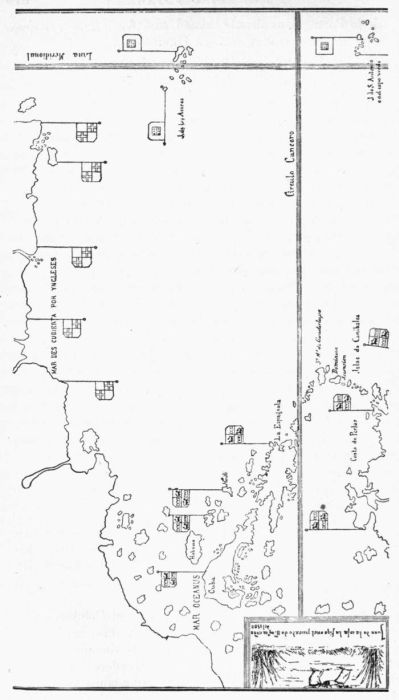

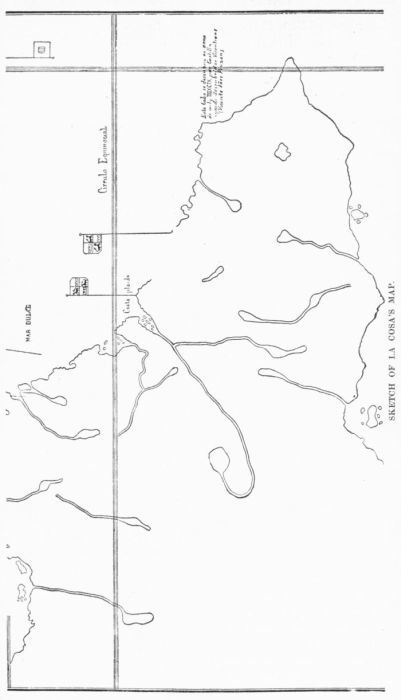

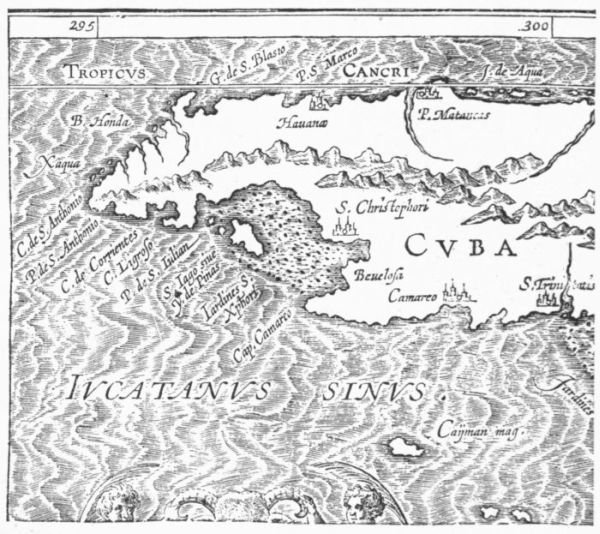

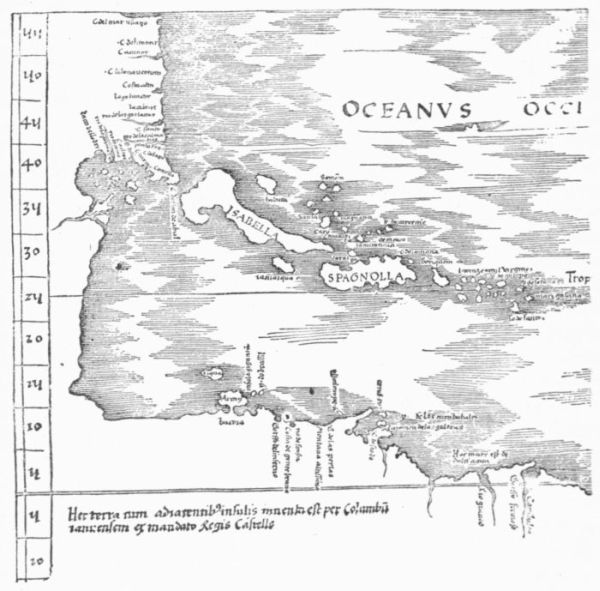

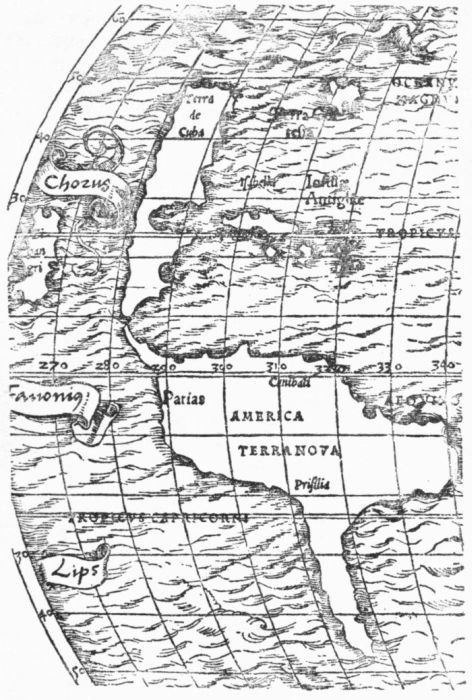

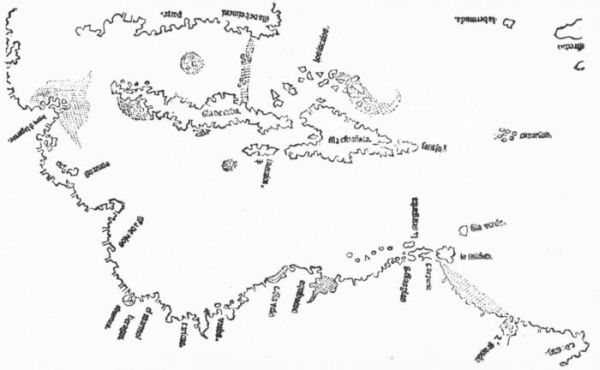

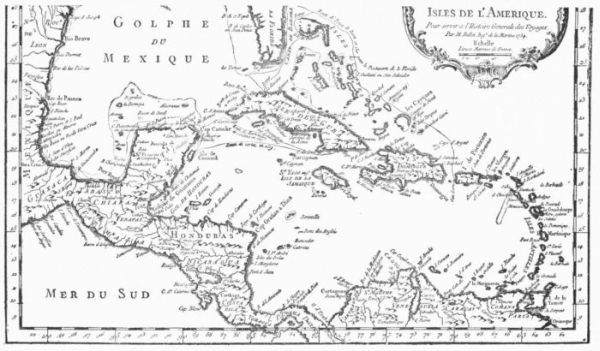

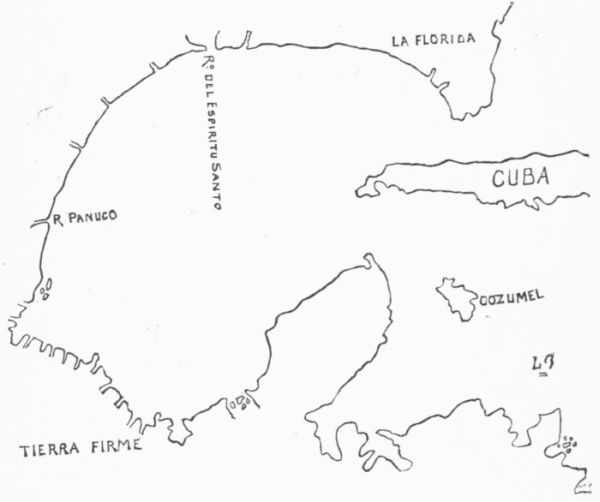

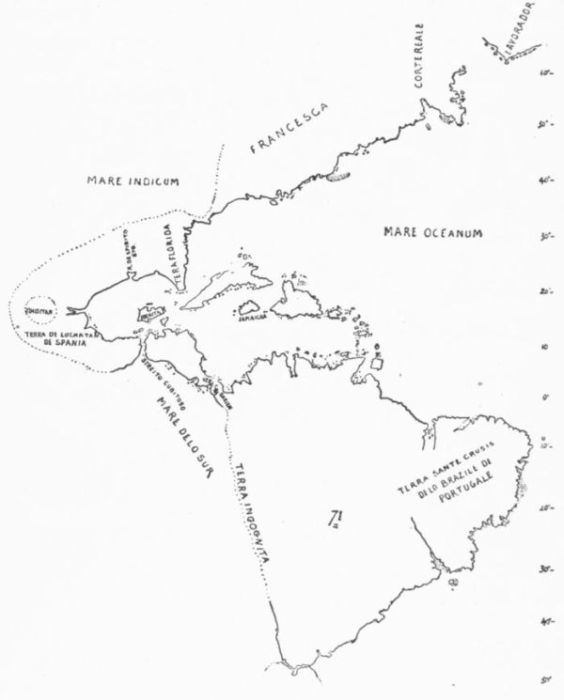

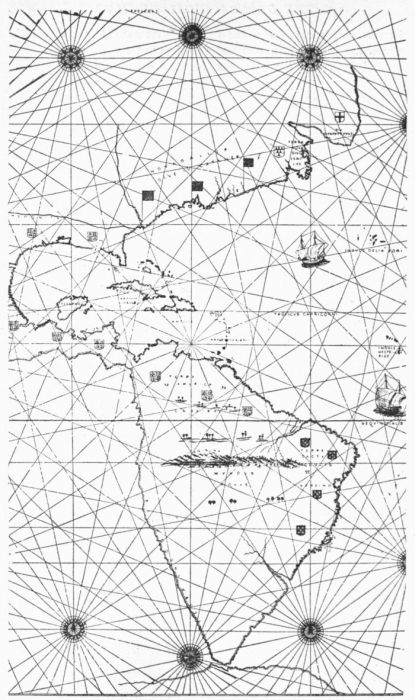

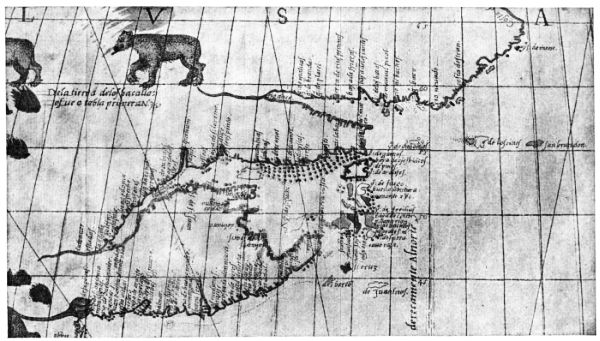

Illustrations: Map of the Gulf of Paria, 353; Pre-Columbian Mappemonde, restored, 357; Ramusio's Map of Española, 369; La Cosa's Map (1500), 380, 381; Ribero's Map of the Antilles (1529), 383; Wytfliet's Cuba, 384, 385. |

||

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

|

| The Degradation and Disheartenment of Columbus (1500) | 388 | |

|

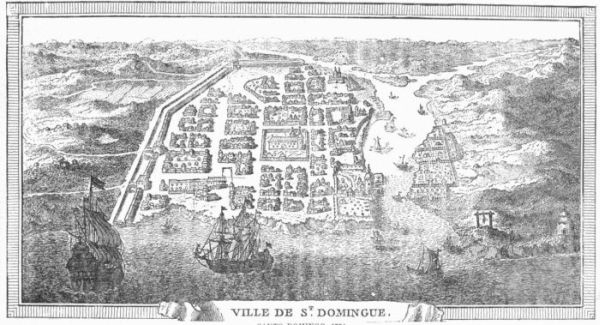

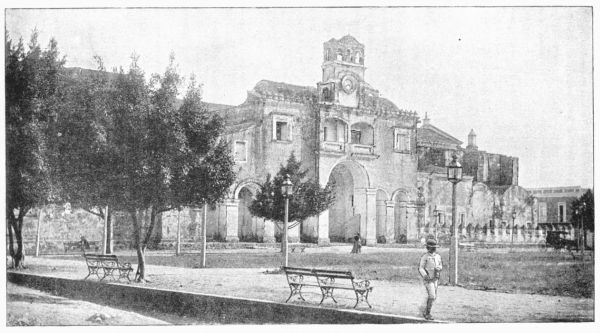

Illustrations: Santo Domingo, 391. |

||

| [Pg x] CHAPTER XVIII. | |

|

| Columbus again in Spain, 1500-1502 | 407 | |

|

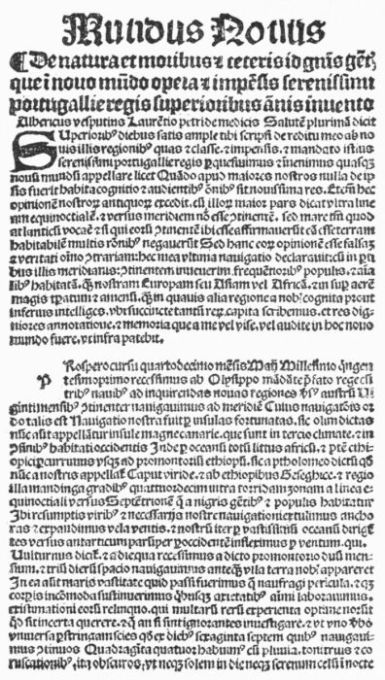

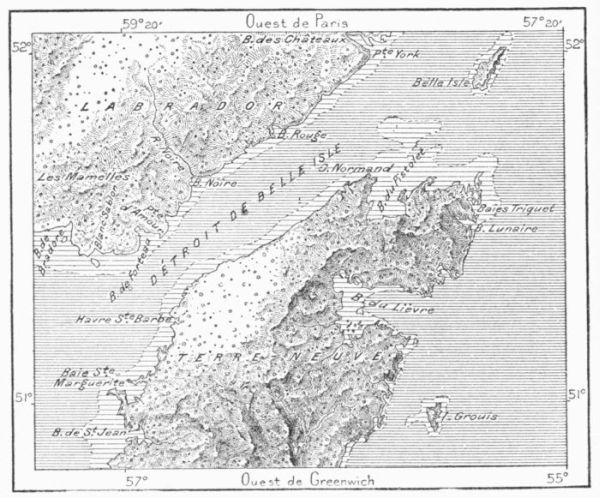

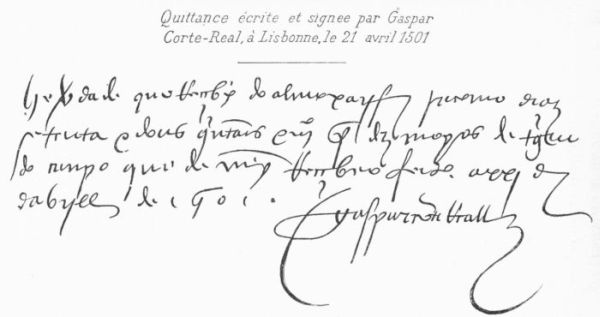

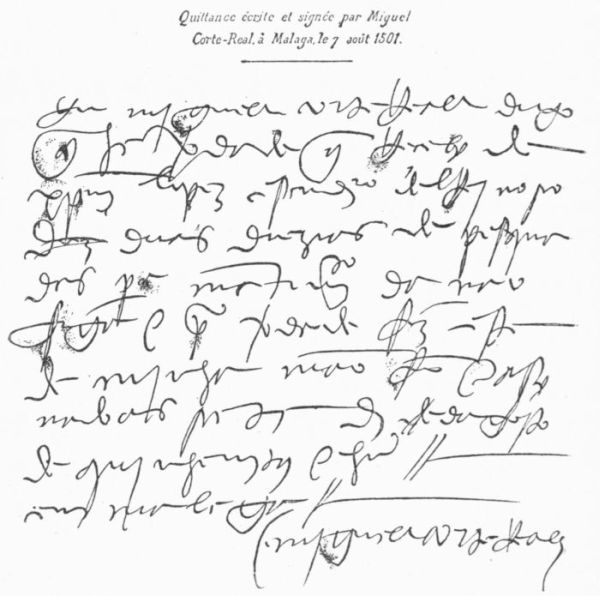

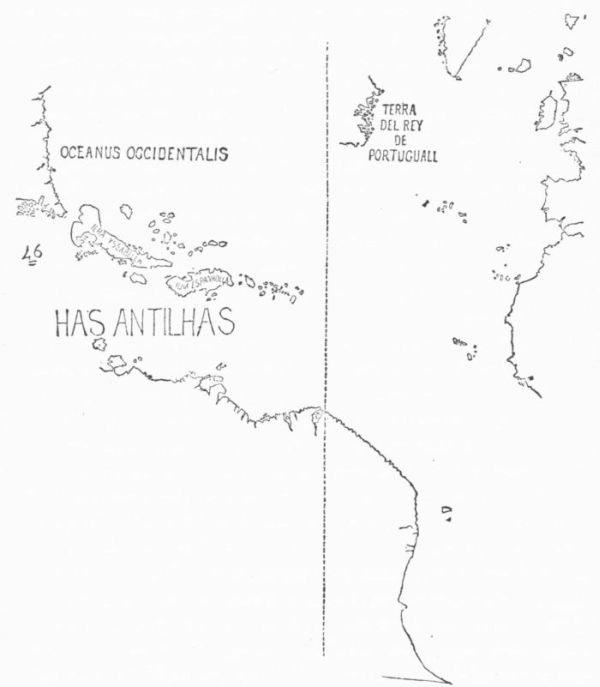

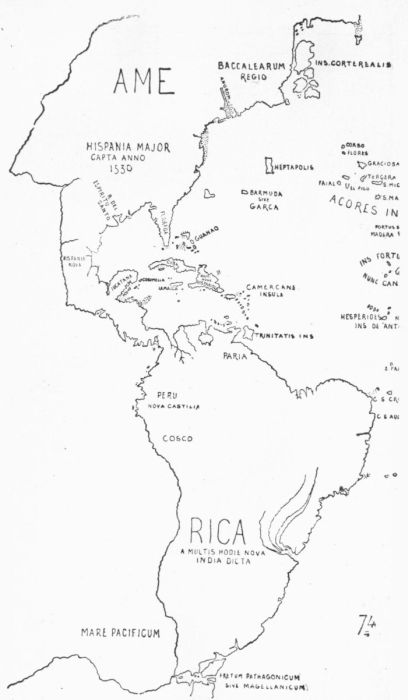

Illustrations: First Page of the Mundus Novus, 411; Map of the Straits of Belle Isle, 413; Manuscript of Gaspar Cortereal, 414; of Miguel Cortereal, 416; the Cantino Map, 419. |

||

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

|

| The Fourth Voyage, 1502-1504 | 437 | |

|

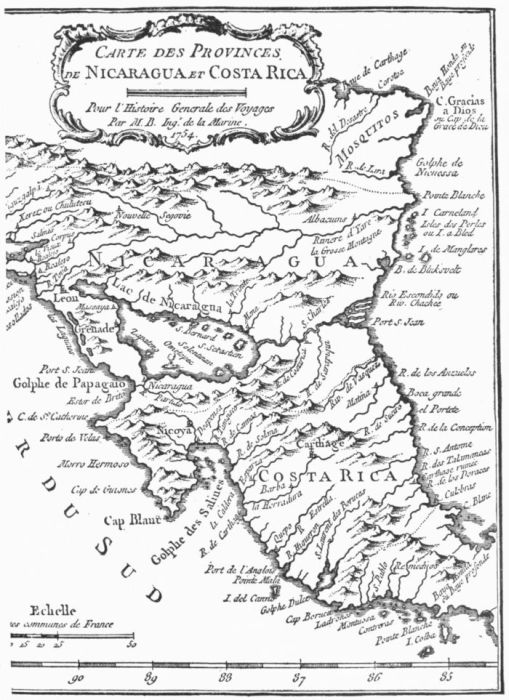

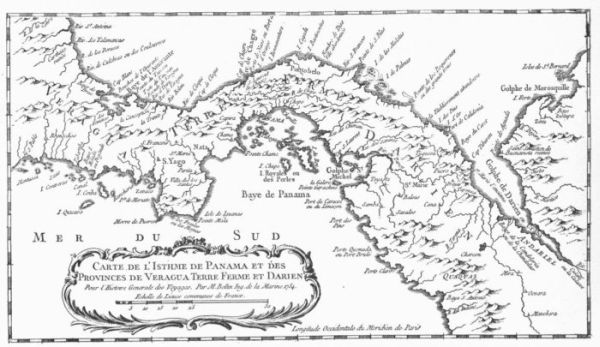

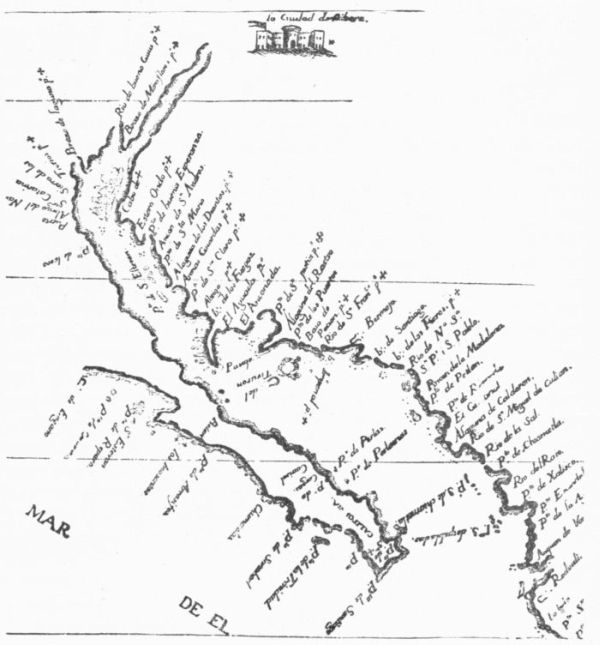

Illustrations: Bellin's Map of Honduras, 443; of Veragua, 446. |

||

| CHAPTER XX. | |

|

| Columbus's Last Years. Death and Character | 477 | |

|

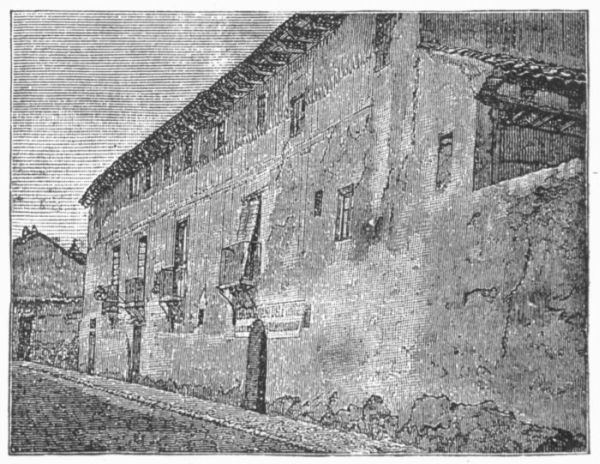

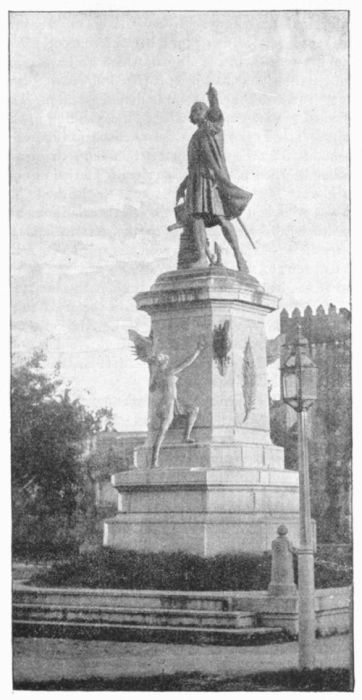

Illustrations: House where Columbus died, 490; Cathedral at Santo Domingo, 493; Statue of Columbus at Santo Domingo, 495. |

||

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

|

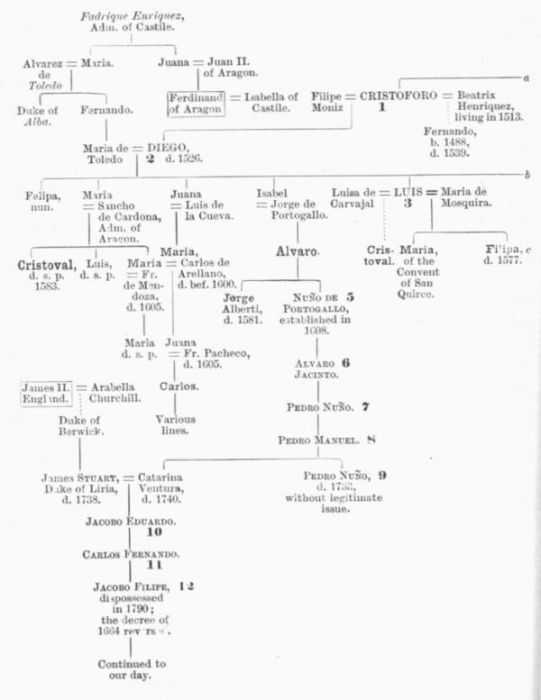

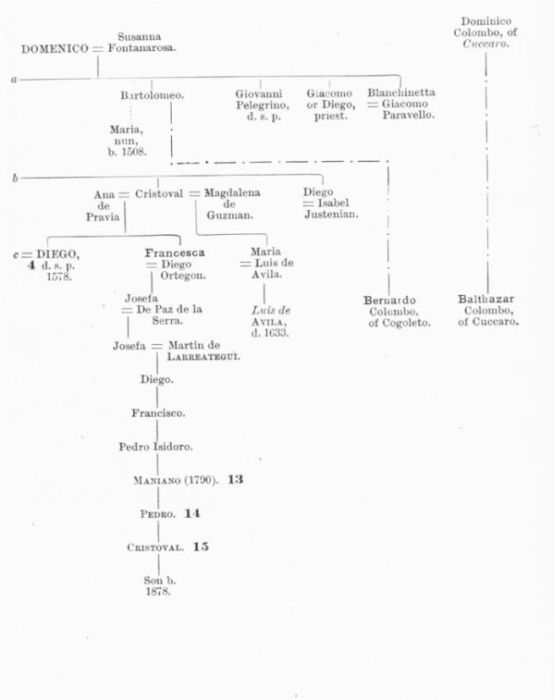

| The Descent of Columbus's Honors | 513 | |

|

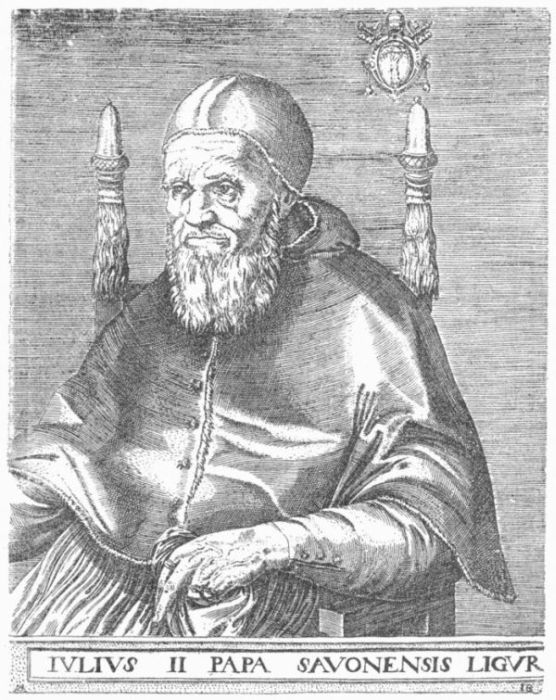

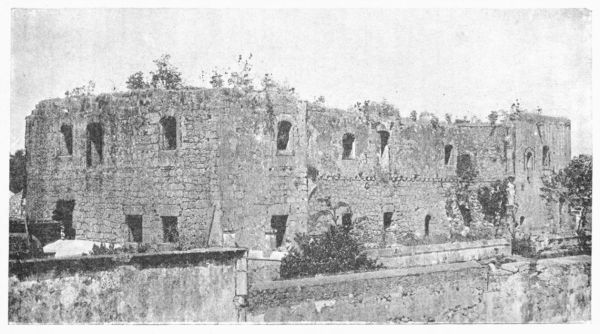

Illustrations: Pope Julius II., 517; Charles the Fifth, 519; Ruins of Diego Colon's House, 521. |

||

| APPENDIX. | |

|

| The Geographical Results | 529 | |

|

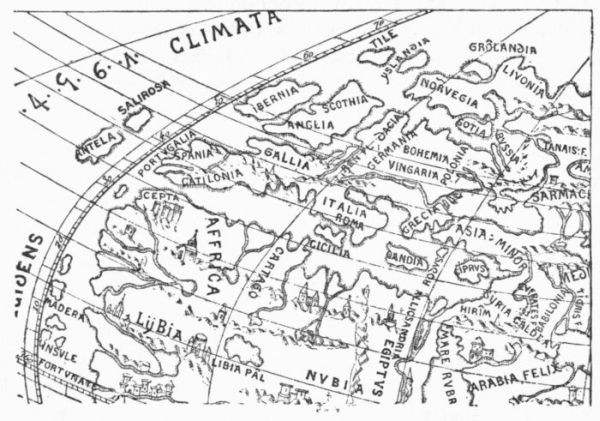

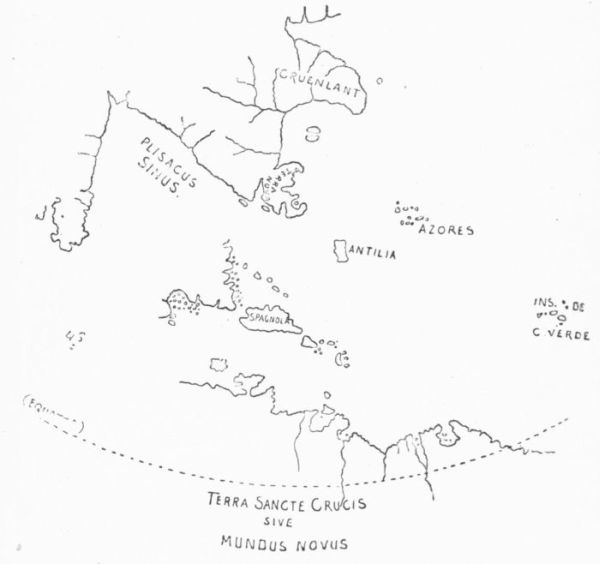

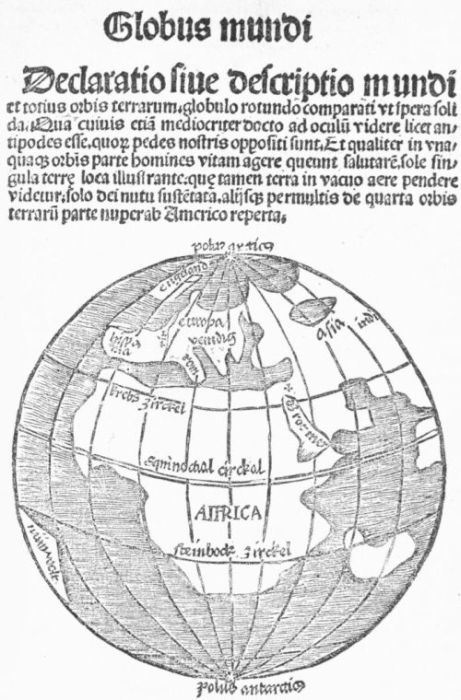

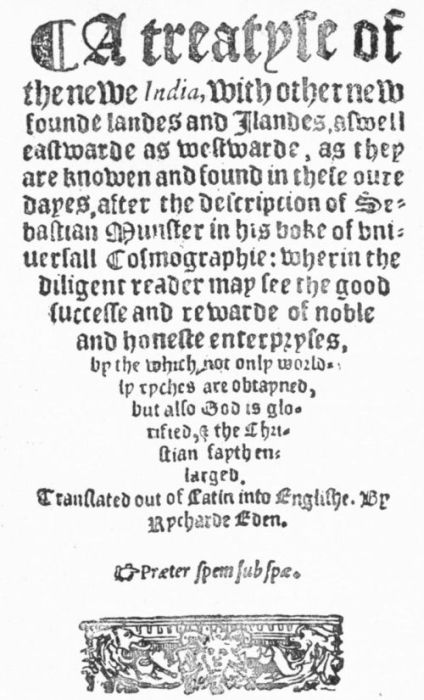

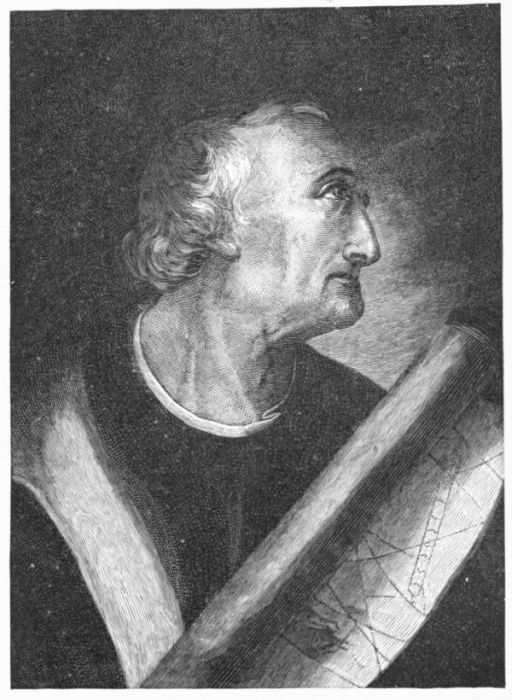

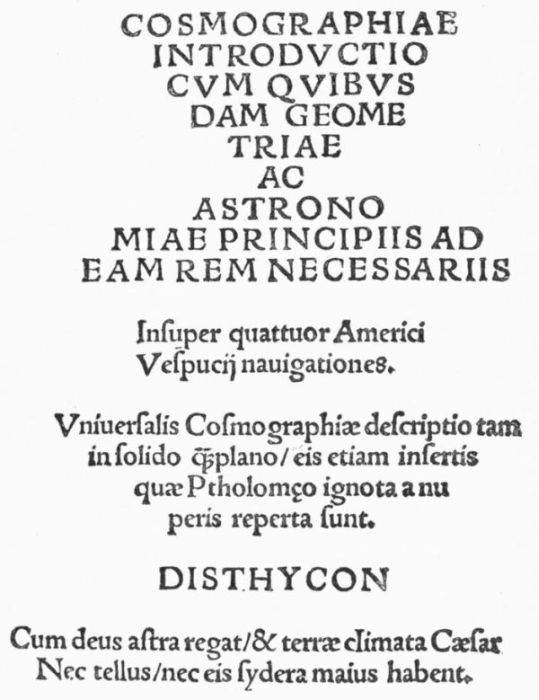

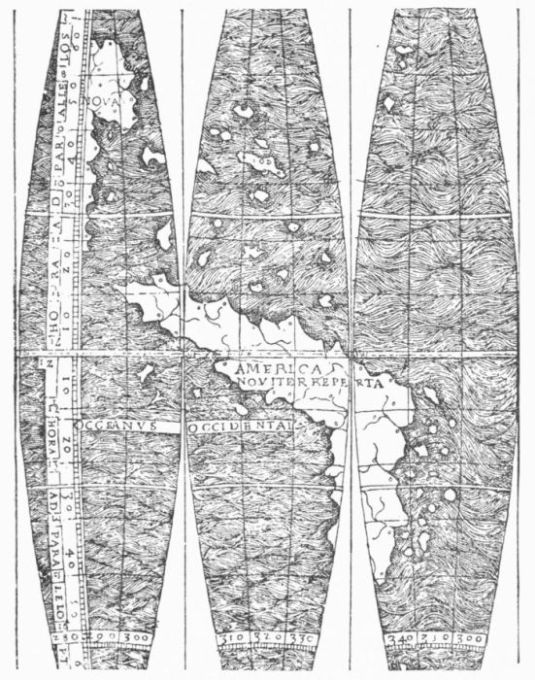

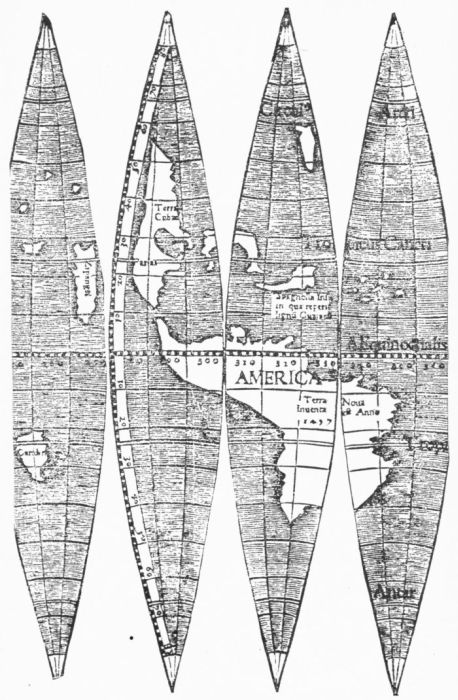

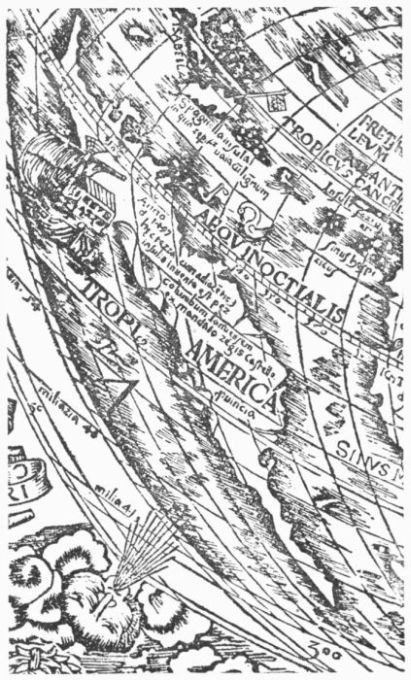

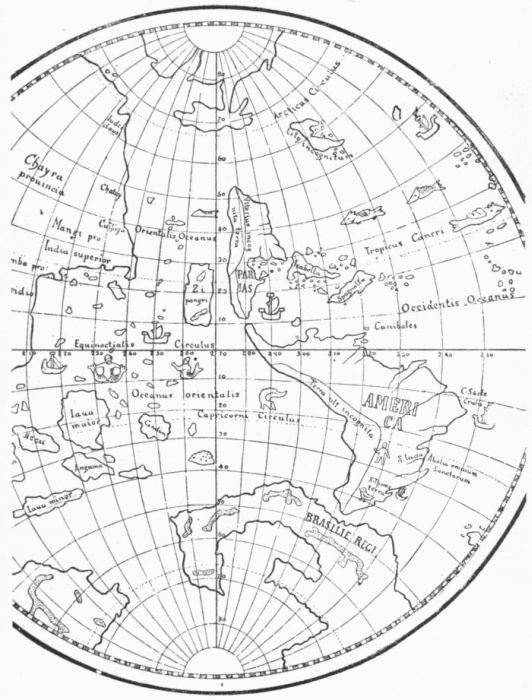

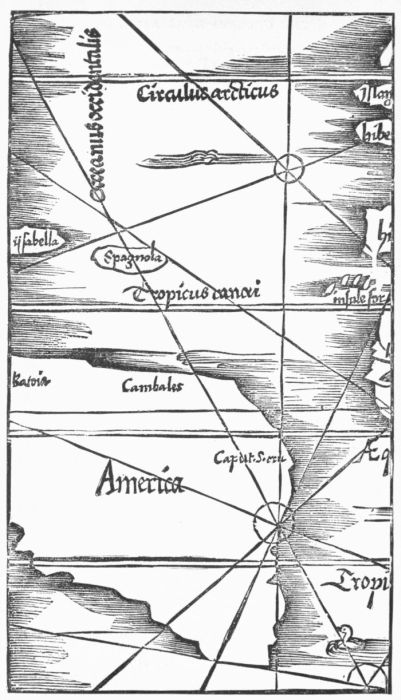

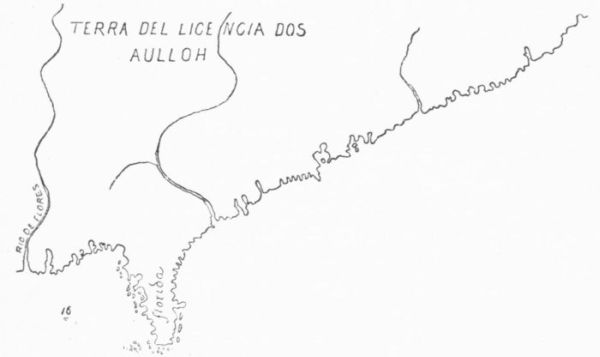

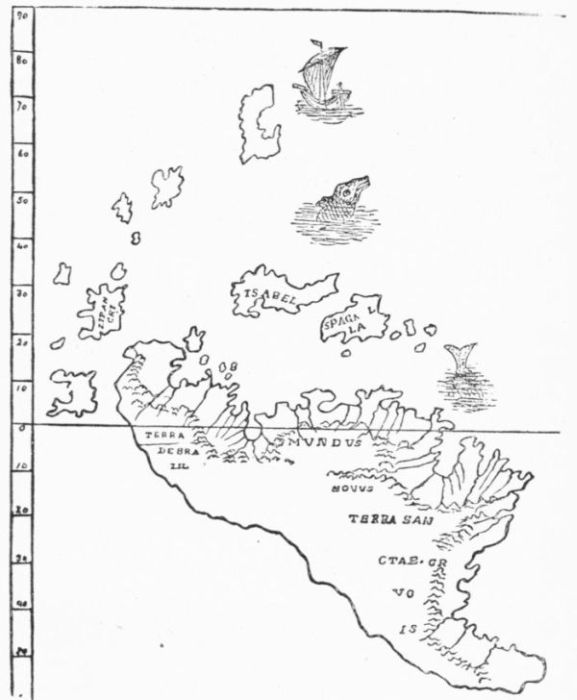

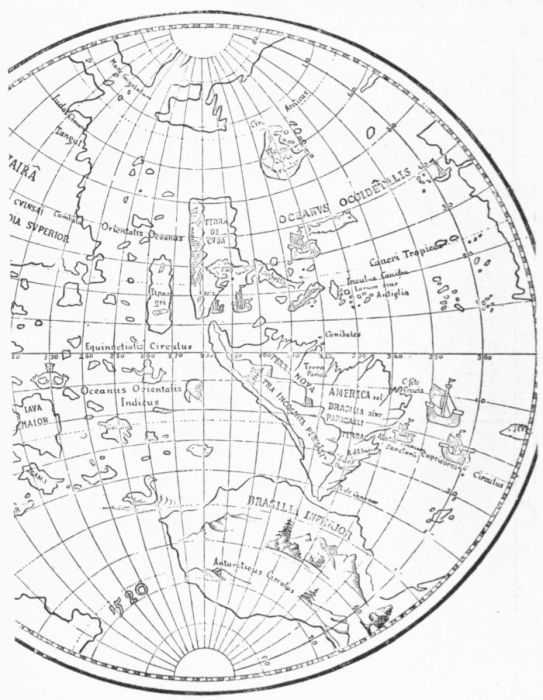

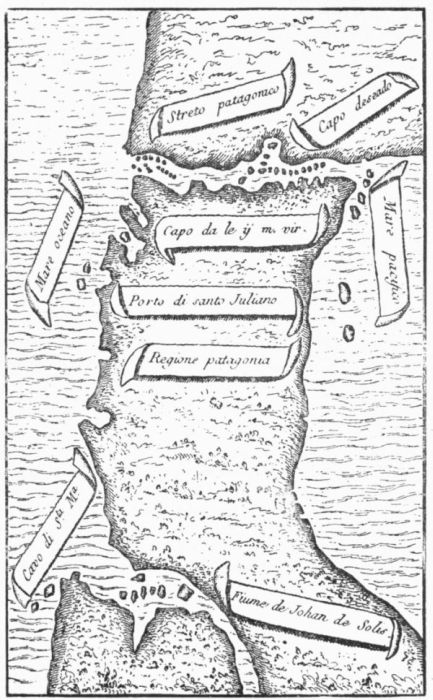

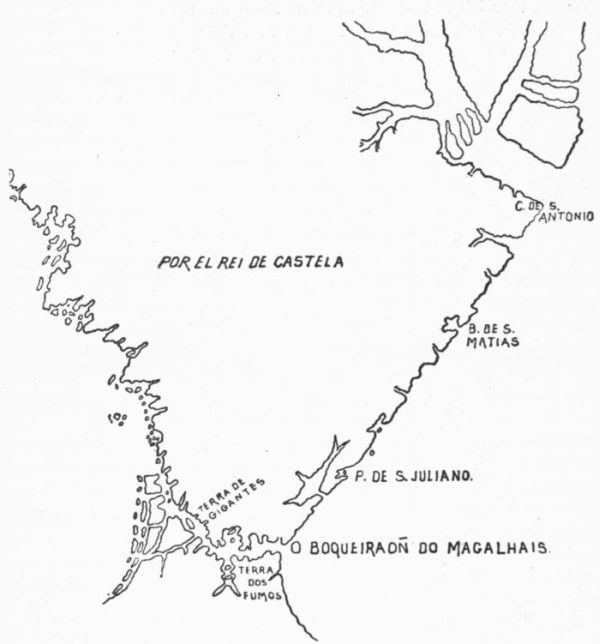

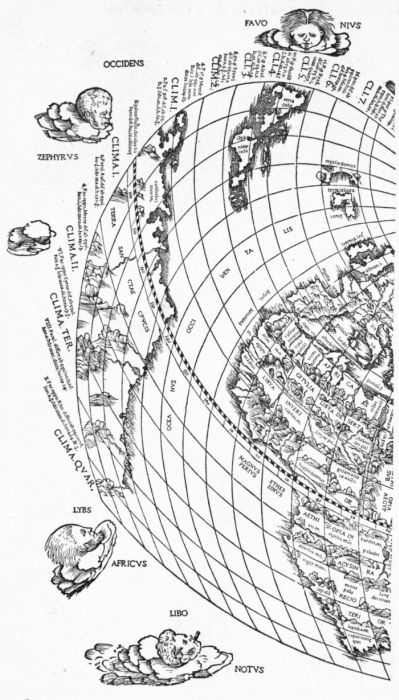

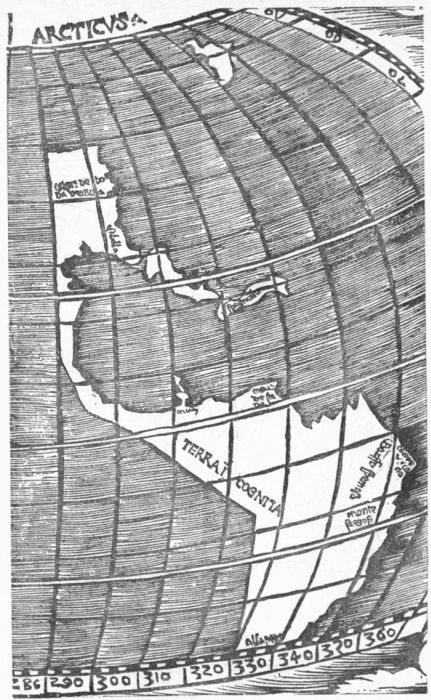

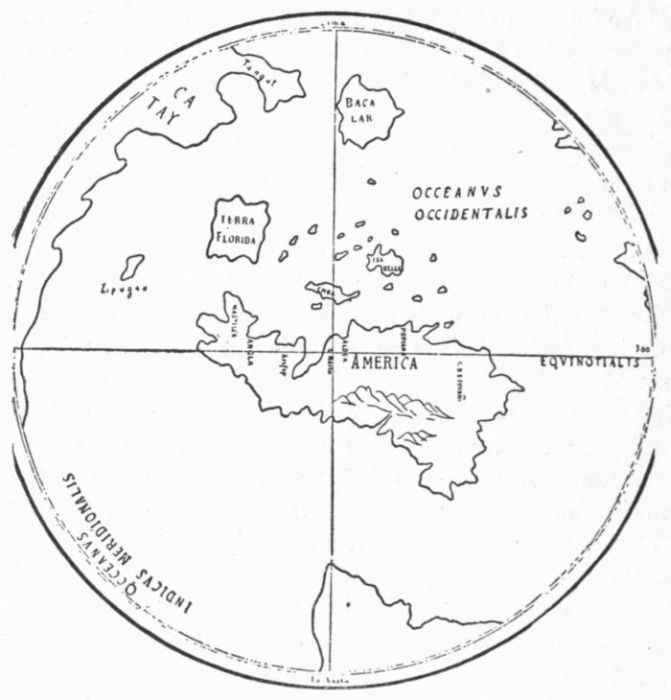

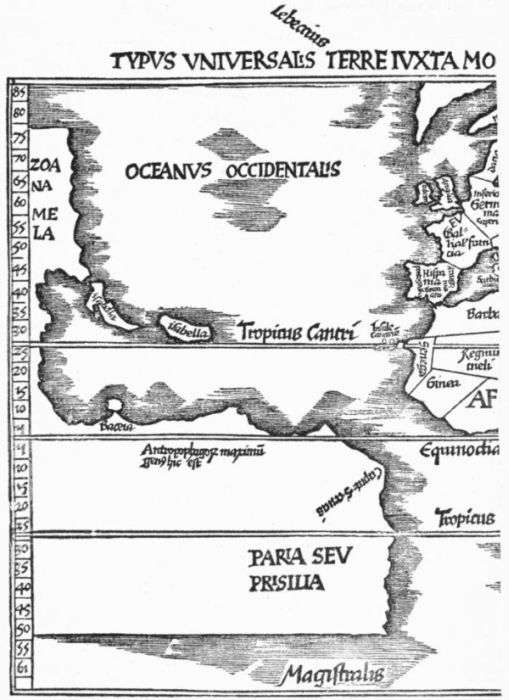

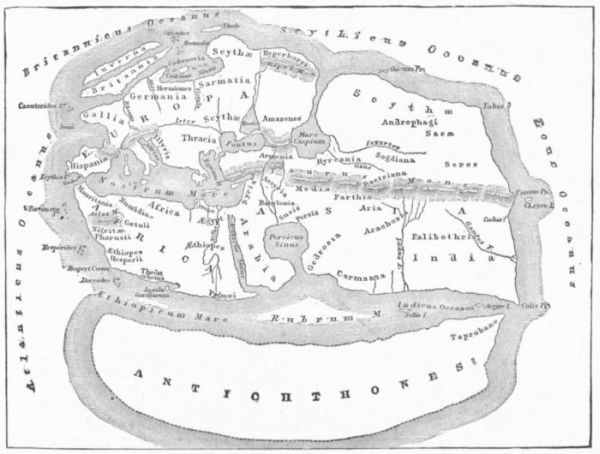

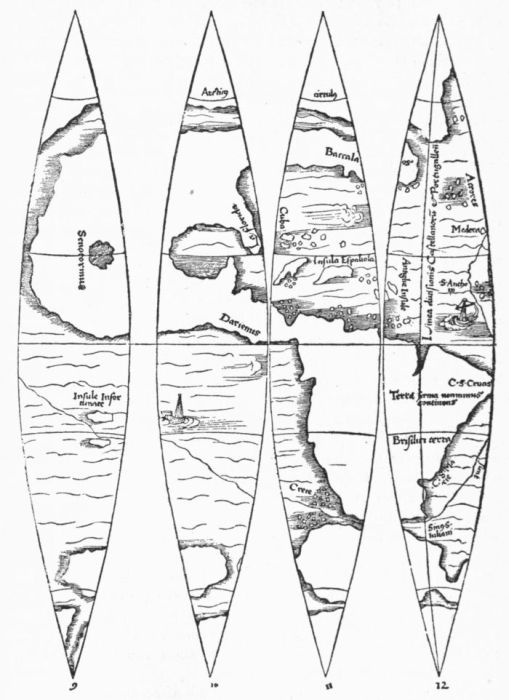

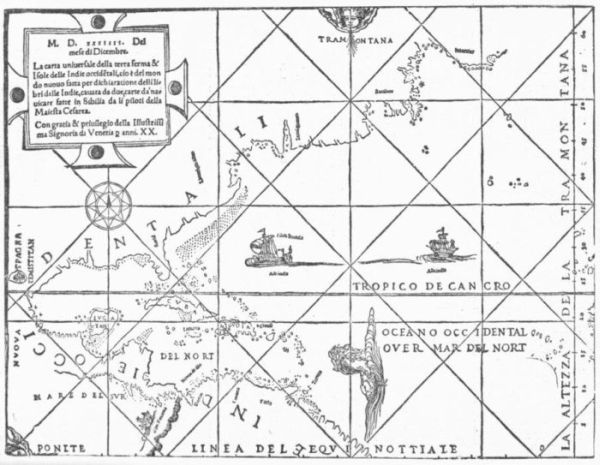

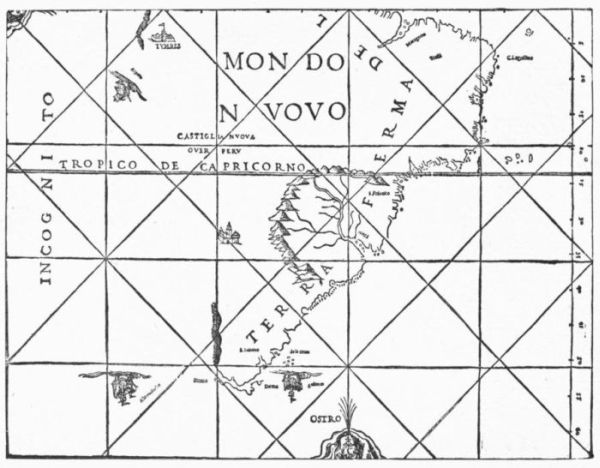

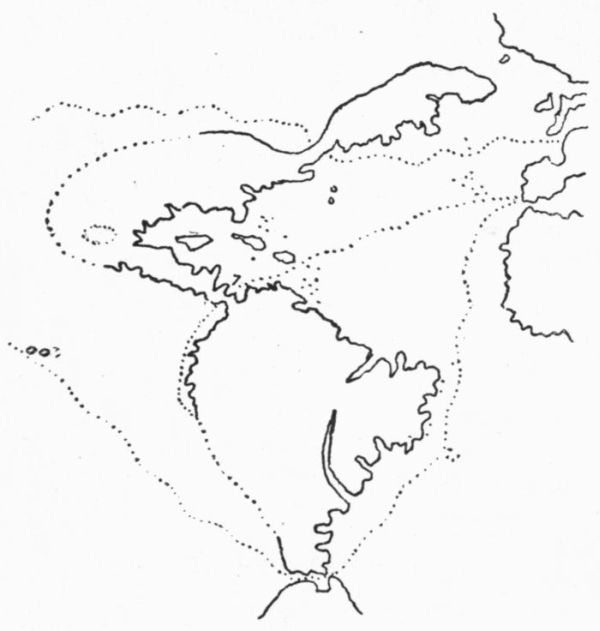

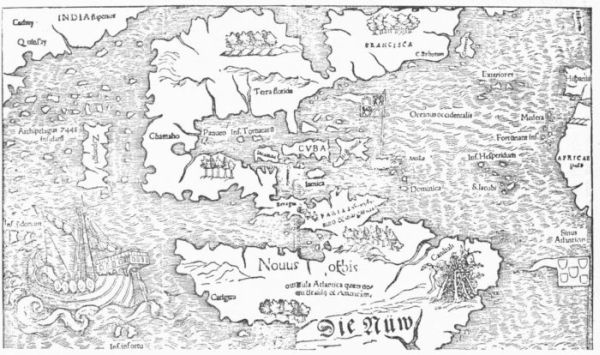

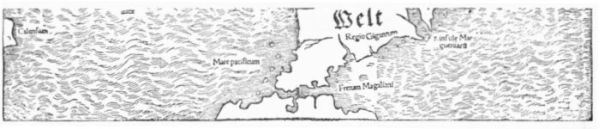

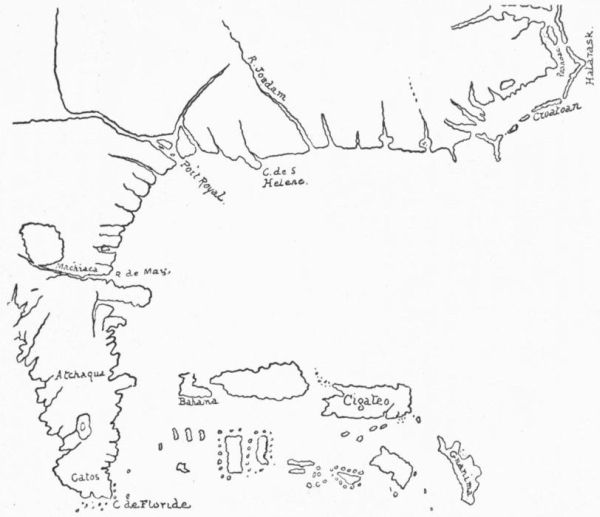

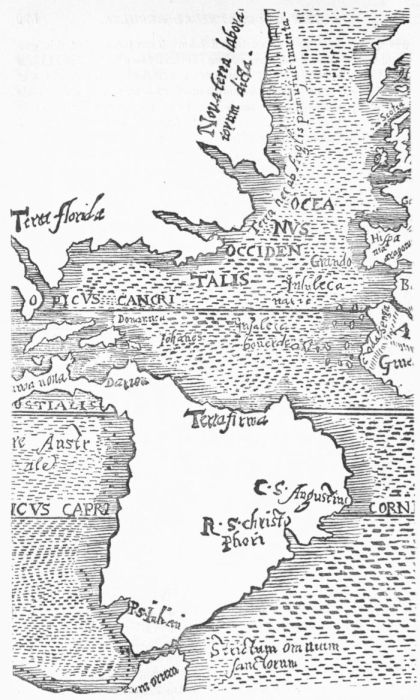

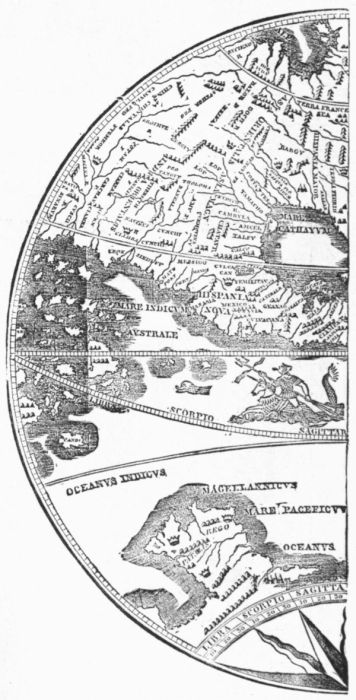

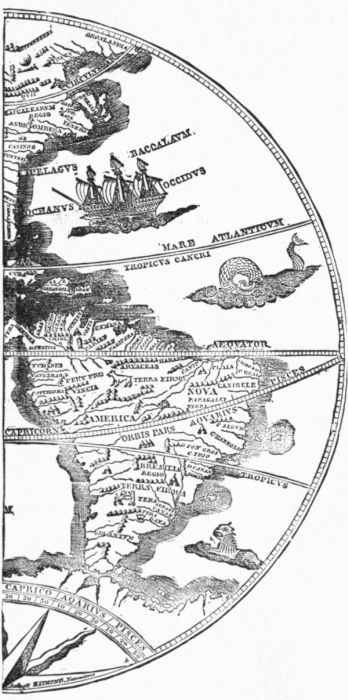

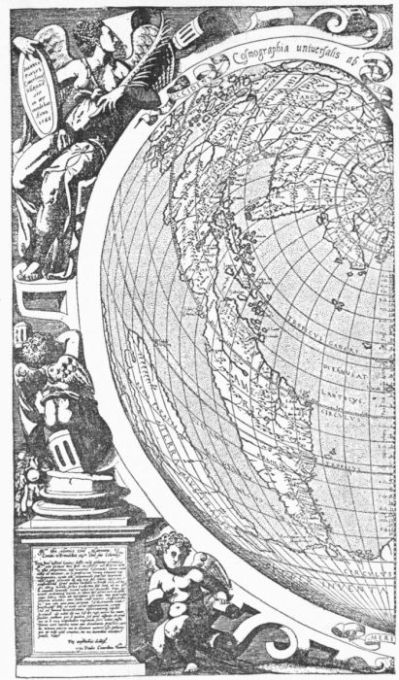

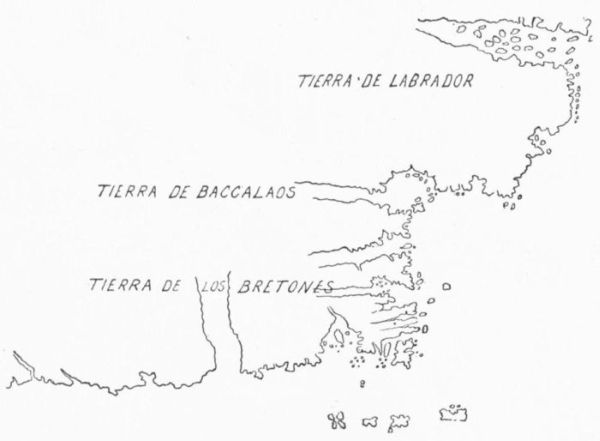

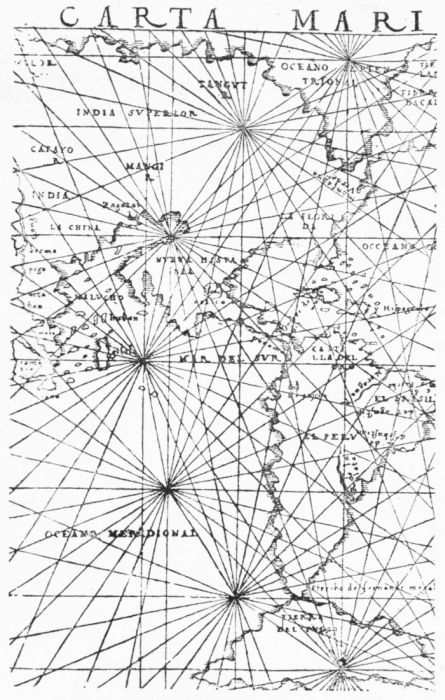

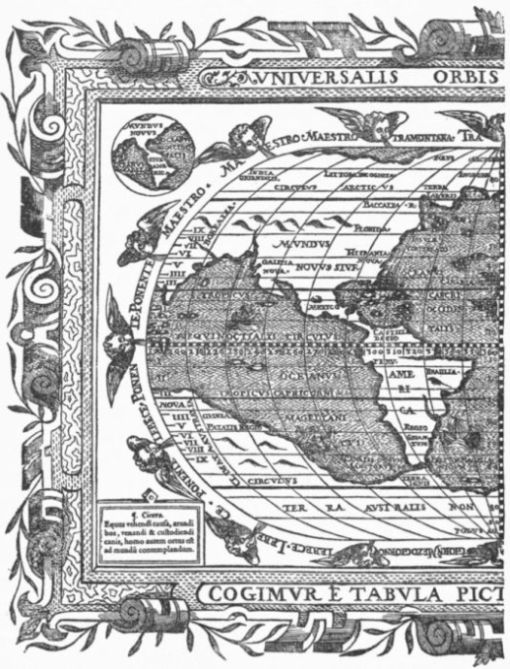

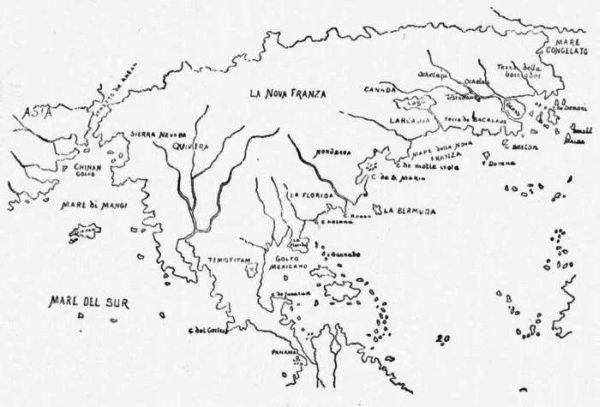

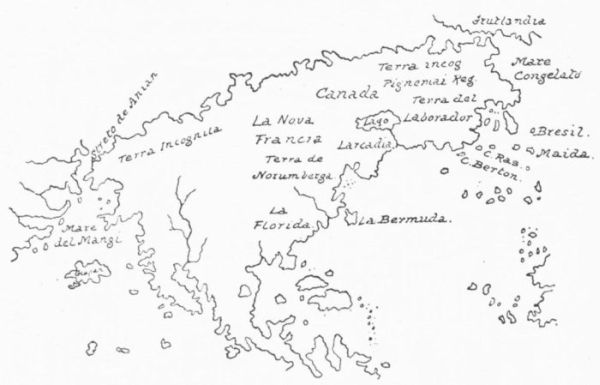

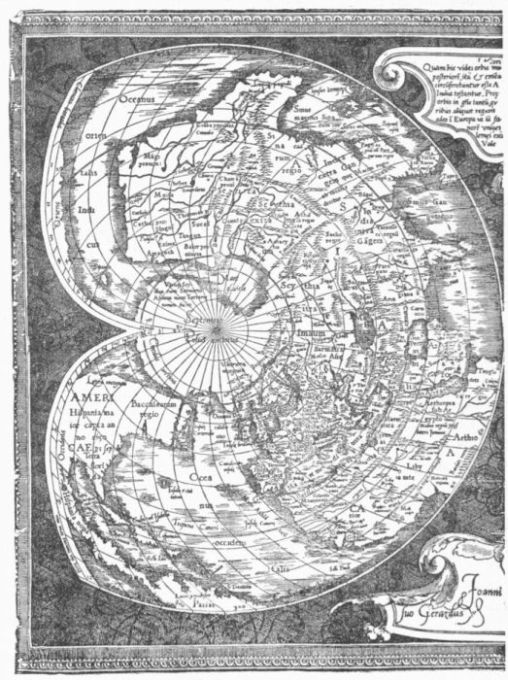

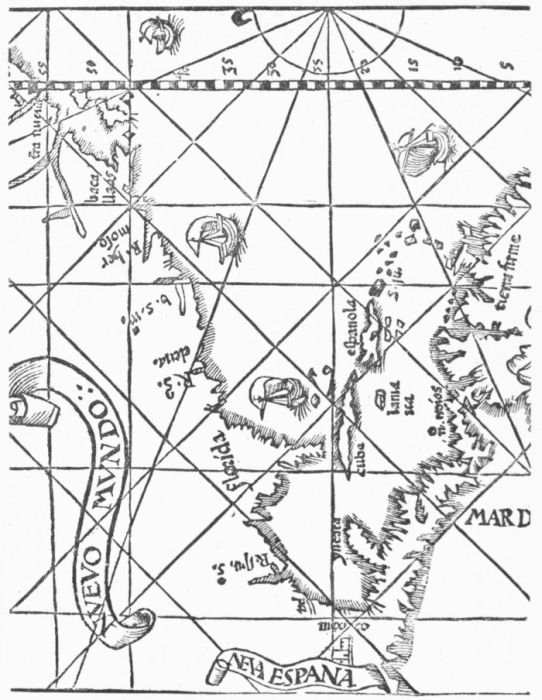

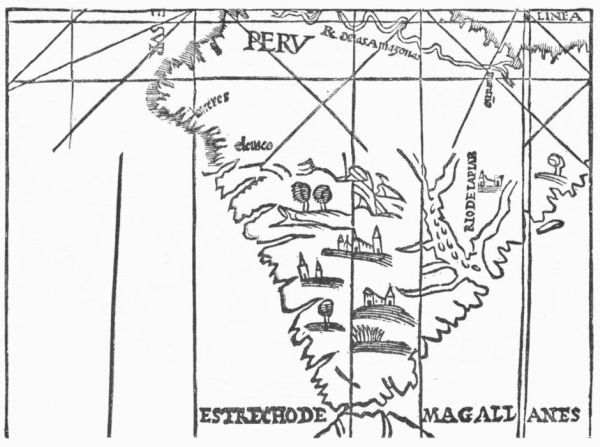

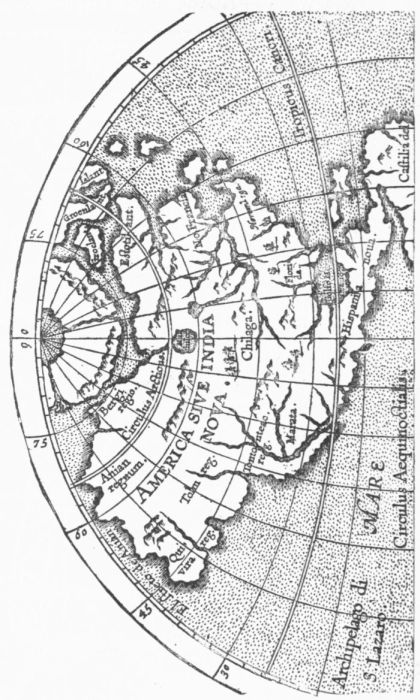

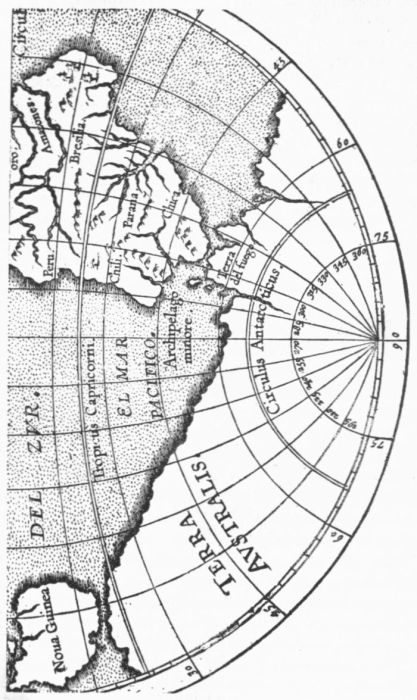

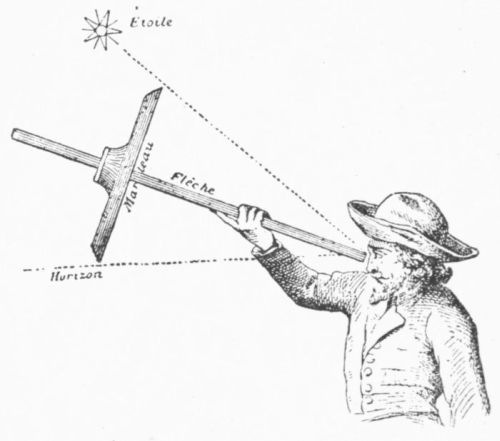

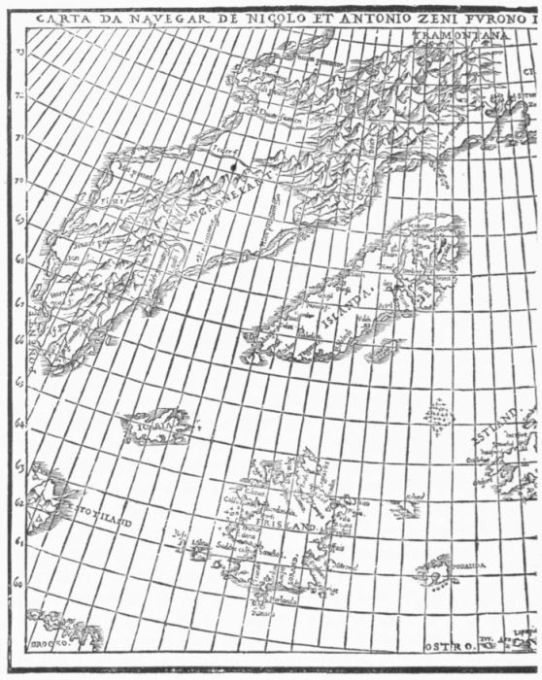

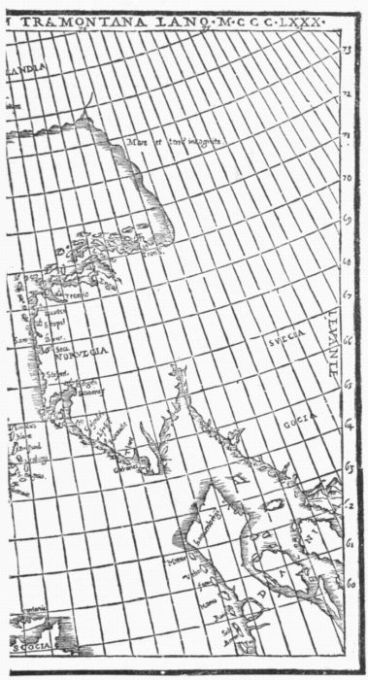

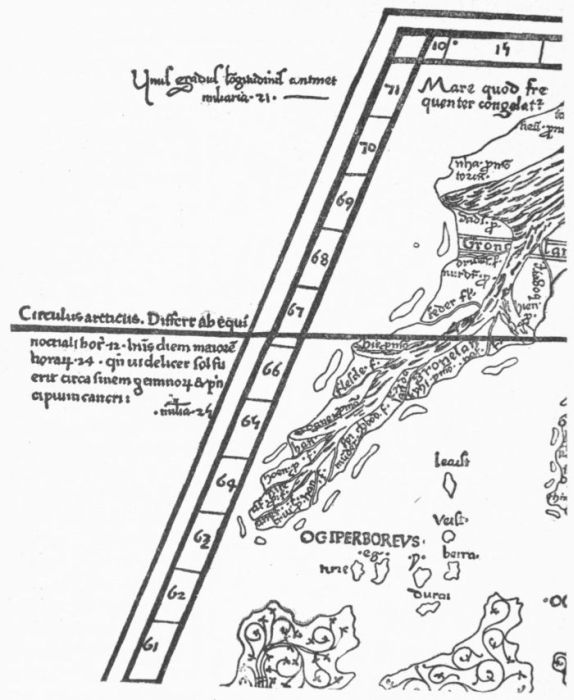

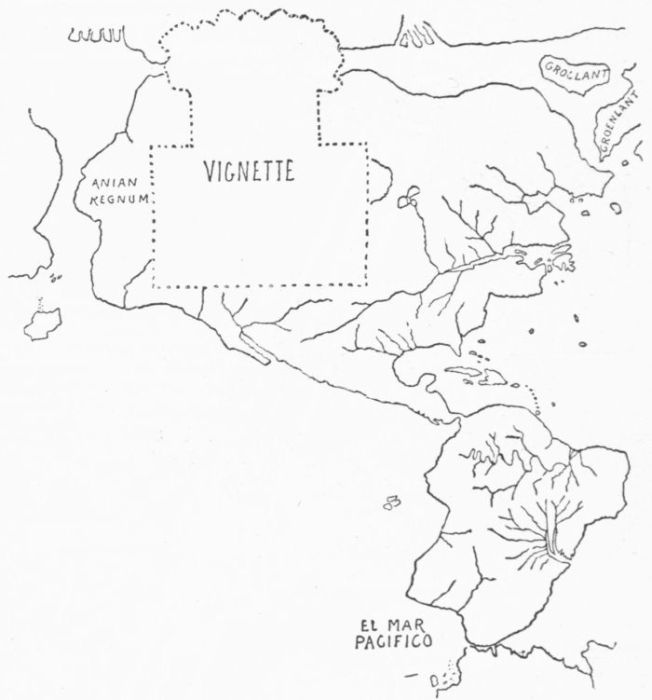

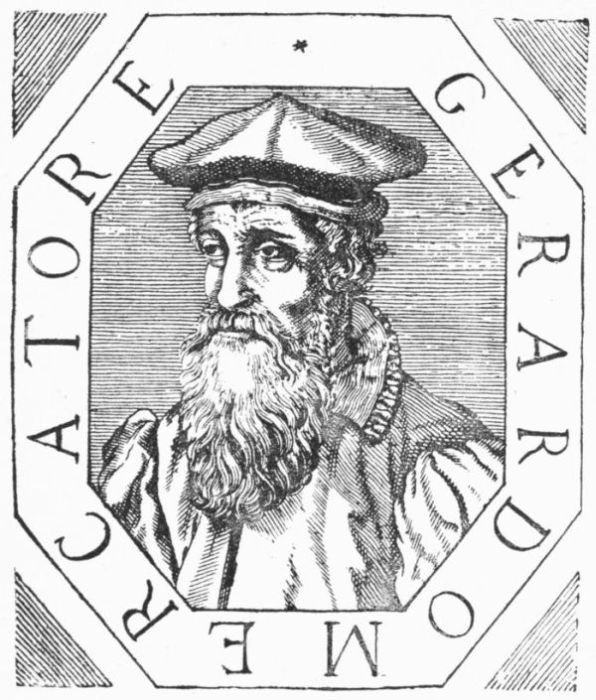

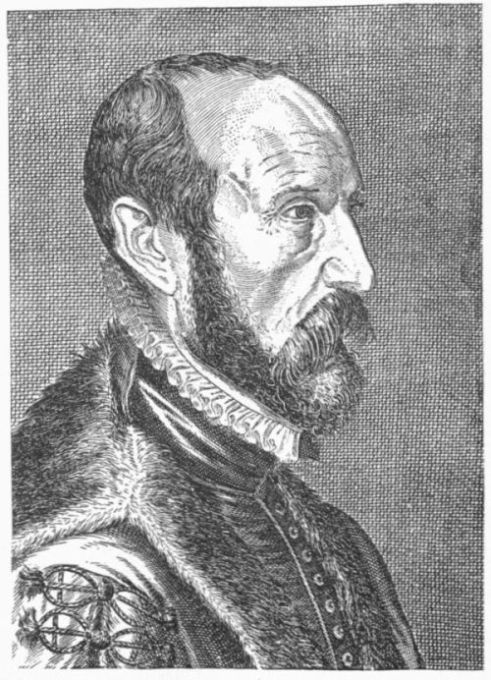

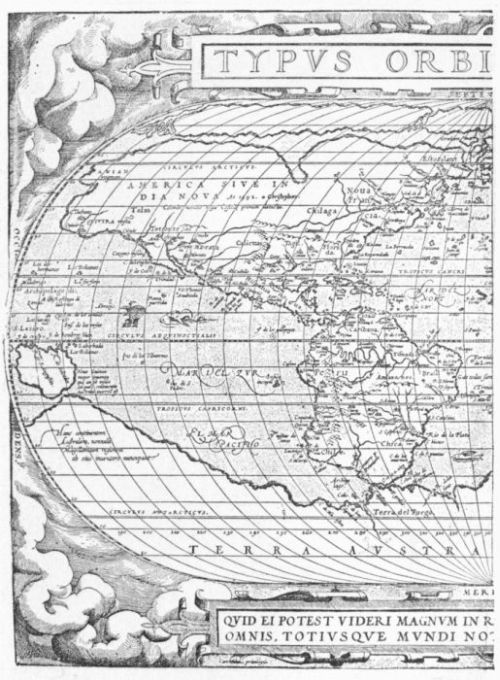

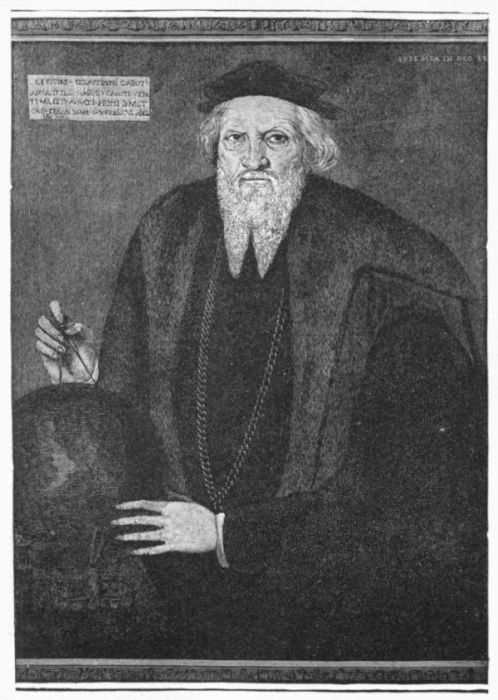

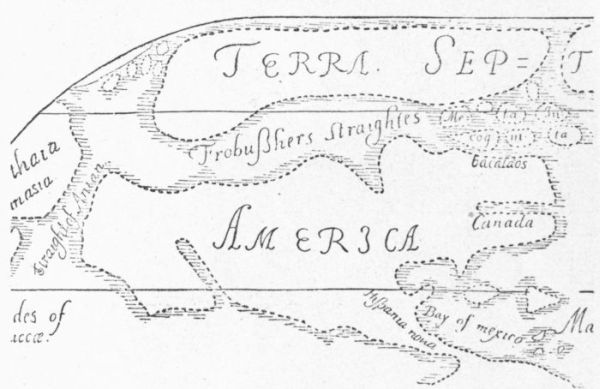

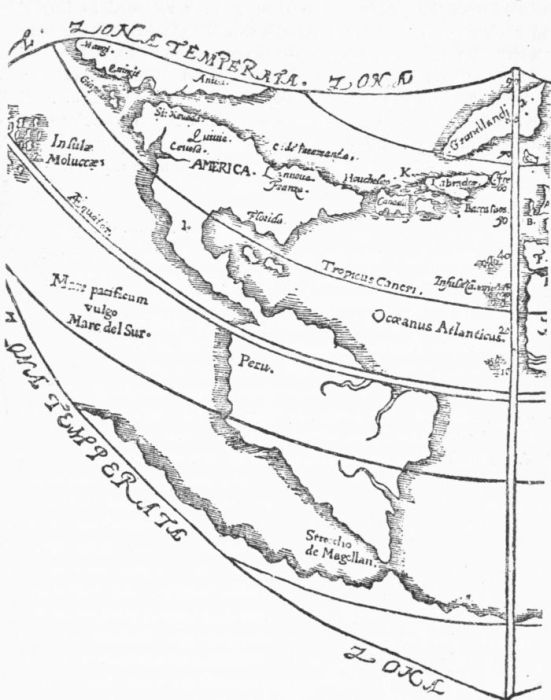

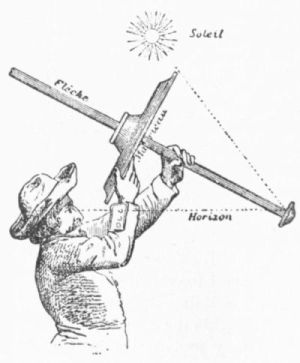

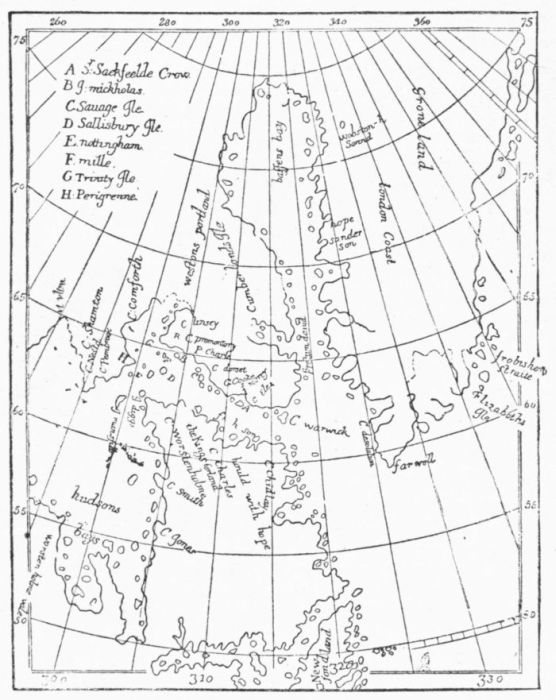

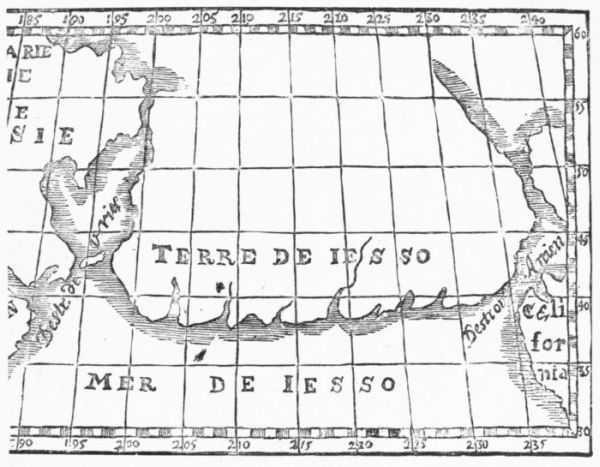

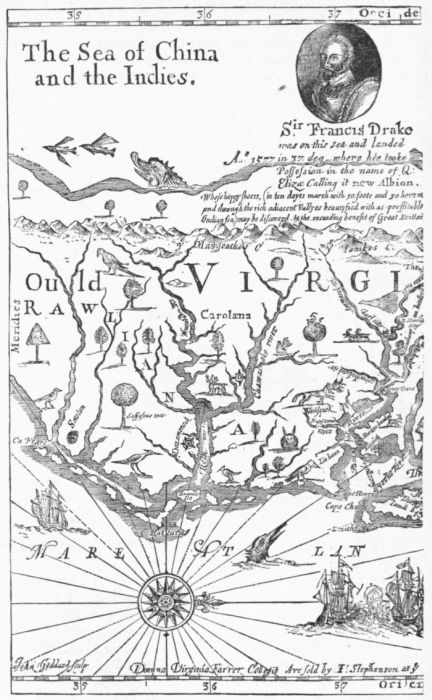

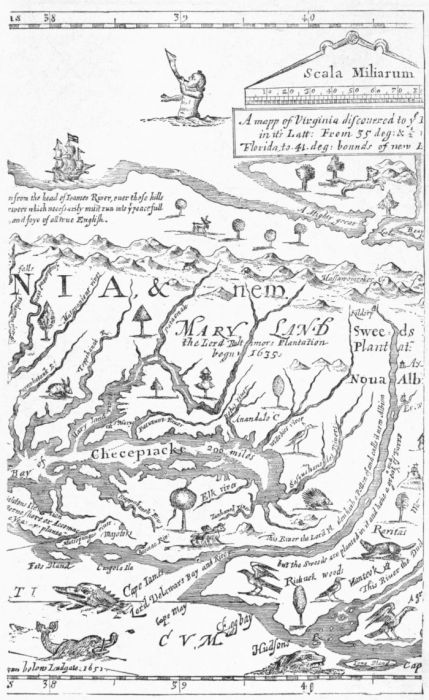

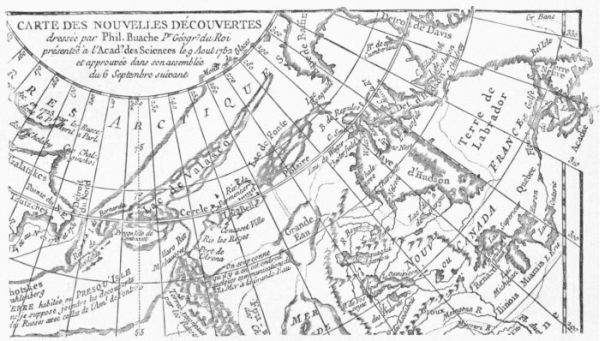

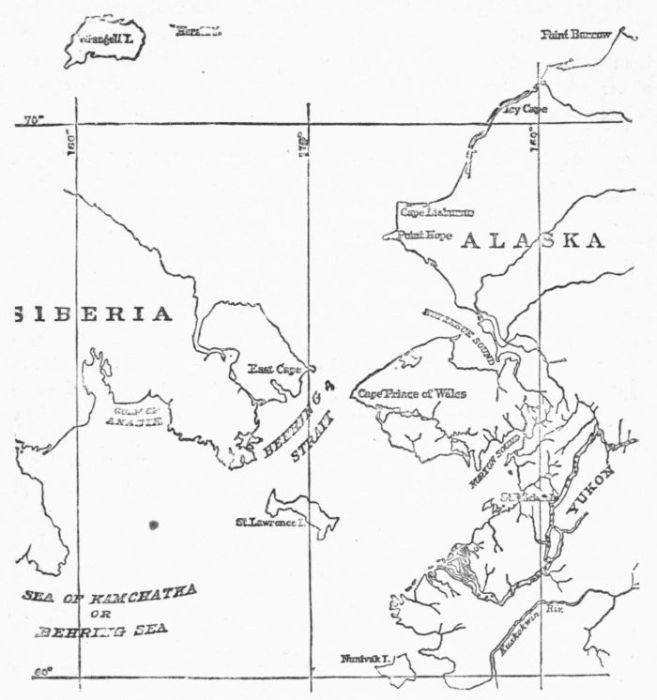

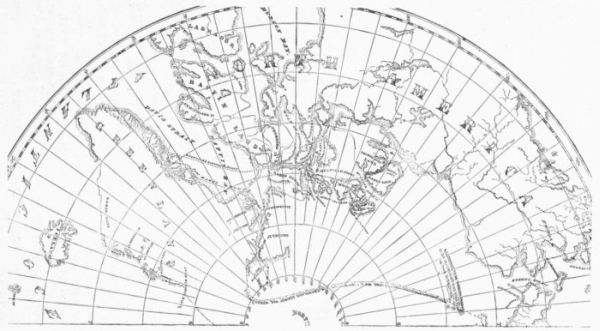

Illustrations: Ptolemy, 530; Map by Donis (1482), 531; Ruysch's Map (1508), 532; the so-called Admiral's Map (1513), 534; Münster's Map (1532), 535; Title-Page of the Globus Mundi, 352; of Eden's Treatyse of the Newe India, 537; Vespucius, 539; Title of the Cosmographiæ Introductio, 541; Map in Ptolemy (1513), 544, 545; the Tross Gores, 547; the Hauslab Globe, 548; the Nordenskiöld Gores, 549; Map by Apianus (1520), 550; Schöner's Globe (1515), 551; Frisius's Map (1522), 552; Peter Martyr's Map (1511), 557; Ponce de Leon, 558; his tracks on the Florida Coast, 559; Ayllon's Map, 561; Balboa, 563; Grijalva, 566; Globe in Schöner's Opusculum, 567; Garay's Map of the Gulf of Mexico, 568; Cortes's Map of the Gulf of Mexico, 569; the Maiollo Map (1527), 570; the Lenox Globe, 571; Schöner's Globe (1520), 572; Magellan, 573; Magellan's Straits by Pizafetta, 575; Modern Map of the Straits, 576; Freire's Map (1546), 578; Sylvanus's Map in Ptolemy (1511), 579; Stobnieza's Map, 580; the Alleged Da Vinci [Pg xi] Sketch-Map, 582; Reisch's Map (1515), 583; Pomponius Mela's World-Map, 584; Vadianus, 585; Apianus, 586; Schöner, 588; Rosenthal or Nuremberg Gores, 590; the Martyr-Oviedo Map (1534), 592, 593; the Verrazano Map, 594; Sketch of Agnese's Map (1536), 595; Münster's Map (1540), 596, 597; Michael Lok's Map (1582), 598 John White's Map, 599; Robert Thorne's Map (1527), 600; Sebastian Münster, 602; House and Library of Ferdinand Columbus, 604; Spanish Map (1527), 605; the Nancy Globe, 606, 607; Map of Orontius Finæus (1532), 608; the same, reduced to Mercator's projection, 609; Cortes, 610; Castillo's California, 611; Extract from an old Portolano of the northeast Coast of North America, 613; Homem's Map (1558), 614; Ziegler's Schondia, 615; Ruscelli's Map (1544), 616; Carta Marina (1548), 617; Myritius's Map (1590), 618; Zaltière's Map (1566), 619; Porcacchi's Map (1572), 620; Mercator's Globe (1538), 622, 623; Münster's America (1545), 624; Mercator's Gores (1541), reduced to a plane projection, 625; Sebastian Cabot's Mappemonde (1544), 626; Medina's Map (1544), 628, 629; Wytfliet's America (1597), 630, 631; the Cross-Staff, 632; the Zeni Map, 634, 635; the Map in the Warsaw Codex (1467), 636, 637; Mercator's America (1569), 638; Portrait of Mercator, 639; of Ortelius, 640; Map by Ortelius (1570), 641; Sebastian Cabot, 642; Frobisher, 643; Frobisher's Chart (1578), 644; Francis Drake, 645; Gilbert's Map (1576), 647; the Back-Staff, 648; Luke Fox's Map of the Arctic Regions (1635), 651; Hennepin's Map of Jesso, 653; Domina Farrer's Map (1651), 654, 655; Buache's Theory of North American Geography (1752), 656; Map of Bering's Straits, 657; Map of the Northwest Passage, 659. |

||

| Index | 661 | |

In considering the sources of information, which are original, as distinct from those which are derivative, we must place first in importance the writings of Columbus himself. We may place next the documentary proofs belonging to private and public archives.

Harrisse points out that Columbus, in his time, acquired such a popular reputation for prolixity that a court fool of Charles the Fifth linked the discoverer of the Indies with Ptolemy as twins in the art of blotting. He wrote as easily as people of rapid impulses usually do, when they are not restrained by habits of orderly deliberation. He has left us a mass of jumbled thoughts and experiences, which, unfortunately, often perplex the historian, while they of necessity aid him.

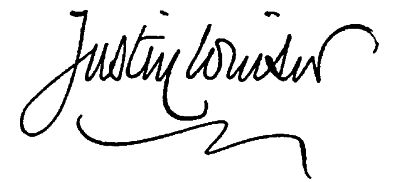

Ninety-seven distinct pieces of writing by the hand of Columbus either exist or are known to have existed. Of such, whether memoirs, relations, or letters, sixty-four are preserved in their entirety. These include twenty-four which are wholly or in part in his own hand. All of them have been printed entire, except one which is in the Biblioteca Colombina, in Seville, the Libro de las Proficias, written apparently between 1501 and 1504, of which only part is in Columbus's own hand. A second document, a memoir addressed to Ferdinand and Isabella, before June, 1497, is now in the collection of the Marquis of San Roman at Madrid, and was printed for the first time by Harrisse in his Christophe Colomb. A third and fourth are in the public archives in Madrid, being letters addressed to the Spanish monarchs: one without date in 1496 or 1497, or perhaps earlier, in 1493, and the [Pg 2] other February 6, 1502; and both have been printed and given in facsimile in the Cartas de Indias, a collection published by the Spanish government in 1877. The majority of the existing private papers of Columbus are preserved in Spain, in the hands of the present representative of Columbus, the Duke of Veragua, and these have all been printed in the great collection of Navarrete. They consist, as enumerated by Harrisse in his Columbus and the Bank of Saint George, of the following pieces: a single letter addressed about the year 1500 to Ferdinand and Isabella; four letters addressed to Father Gaspar Gorricio,—one from San Lucar, April 4, 1502; a second from the Grand Canaria, May, 1502; a third from Jamaica, July 7, 1503; and the last from Seville, January 4, 1505;—a memorial addressed to his son, Diego, written either in December, 1504, or in January, 1505; and eleven letters addressed also to Diego, all from Seville, late in 1504 or early in 1505.

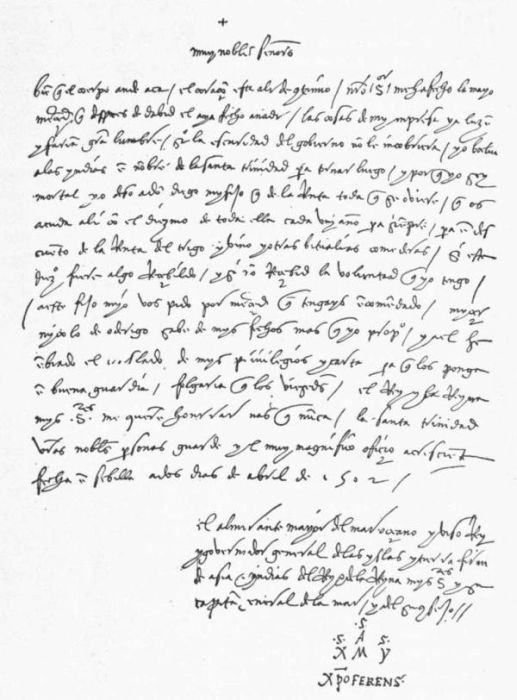

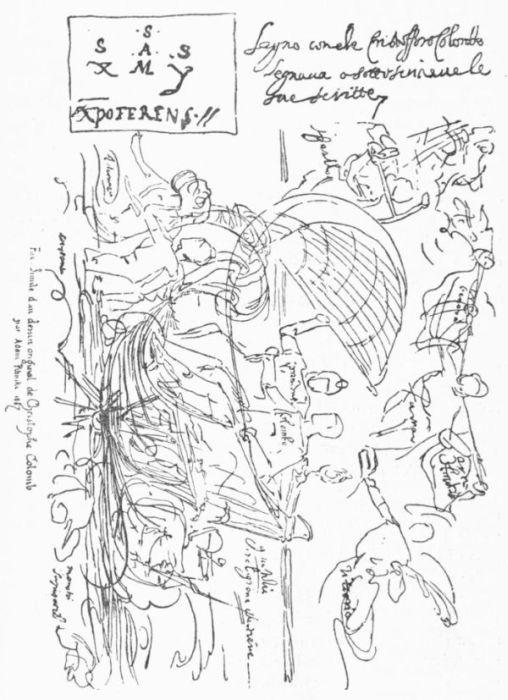

MANUSCRIPT OF COLUMBUS

MANUSCRIPT OF COLUMBUSWithout exception, the letters of Columbus of which we have knowledge were written in Spanish. Harrisse has conjectured that his stay in Spain made him a better master of that language than the poor advantages of his early life had made him of his mother tongue.

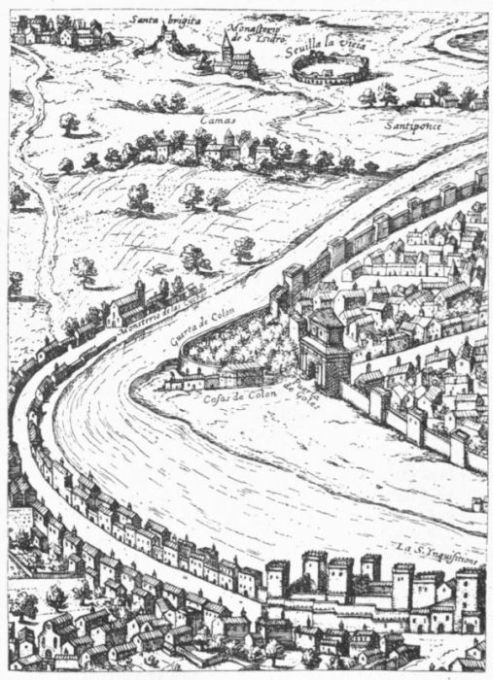

Columbus was more careful of the documentary proofs of his titles and privileges, granted in consequence of his discoveries, than of his own writings. He had more solicitude to protect, by such records, the pecuniary and titular rights of his descendants than to preserve those personal papers which, in the eyes of the historian, are far more valuable. These attested evidences of his rights were for a while inclosed in an iron chest, kept at his tomb in the monastery of Las Cuevas, near Seville, and they remained down to 1609 in the custody of the Carthusian friars of that convent. At this date, Nuño de Portugallo having been declared the heir to the estate and titles of Columbus, the papers were transferred to his keeping; and in the end, by legal decision, they passed to that Duke of Veragua who was the grandfather of the present duke, who in due time inherited these public memorials, and now preserves them in Madrid.

In 1502 there were copies made in book form, known as the Codex Diplomaticus, of these and other pertinent documents, raising the number from thirty-six to forty-four. These copies were attested at Seville, by order of the Admiral, who then aimed to place them so that the record of his deeds and rights should not be lost. Two copies seem to have been sent by him through different channels to Nicoló Oderigo, the Genoese ambassador in Madrid; and in 1670 both of these copies came from a descendant of that ambassador as a gift to the Republic of Genoa. Both of these later disappeared from its archives. A third copy was sent to Alonso Sanchez de Carvajal, the factor of Columbus in Española, and this copy is not now known. A fourth copy was deposited in the monastery of Las Cuevas, near Seville, to be later sent to Father Gorricio. It is very likely this last copy which is mentioned by Edward Everett in a note to his oration at Plymouth (Boston, 1825, p. 64), where, referring to the two copies sent to Oderigo as the only ones made by the order of Columbus, as then understood, he adds: "Whether the two manuscripts thus mentioned be the only ones in existence may admit of doubt. When I was in Florence, in 1818, a small folio manuscript was brought to me, written on parchment, apparently two or three centuries old, in binding once very rich, but now worn, containing a series of [Pg 4] documents in Latin and Spanish, with the following title on the first blank page: 'Treslado de las Bullas del Papa Alexandro VI., de la concession de las Indias y los titulos, privilegios y cedulas reales, que se dieron a Christoval Colon.' I was led by this title to purchase the book." After referring to the Codice, then just published, he adds: "I was surprised to find my manuscript, as far as it goes, nearly identical in its contents with that of Genoa, supposed to be one of the only two in existence. My manuscript consists of almost eighty closely written folio pages, which coincide precisely with the text of the first thirty-seven documents, contained in two hundred and forty pages of the Genoese volume."

Caleb Cushing says of the Everett manuscript, which he had examined before he wrote of it in the North American Review, October, 1825, that, "so far as it goes, it is a much more perfect one than the Oderigo manuscript, as several passages which Spotorno was unable to decipher in the latter are very plain and legible in the former, which indeed is in most complete preservation." I am sorry to learn from Dr. William Everett that this manuscript is not at present easily accessible.

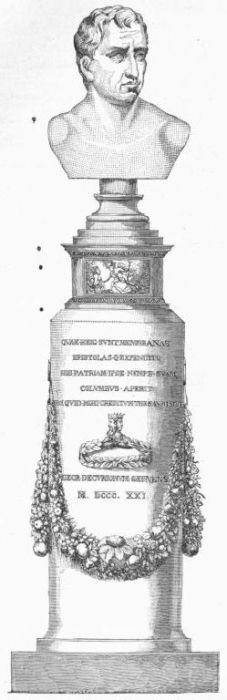

Of the two copies named above as having disappeared from the archives of Genoa, Harrisse at a late day found one in the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Paris. It had been taken to Paris in 1811, when Napoleon I. caused the archives of Genoa to be sent to that city, and it was not returned when the chief part of the documents was recovered by Genoa in 1815. The other copy was in 1816 among the papers of Count Cambiaso, and was bought by the Sardinian government, and given to the city of Genoa, where it is now deposited in a marble custodia, which, surmounted by a bust of Columbus, stands at present in the main hall of the palace of the municipality. This "custodia" is a pillar, in which a door of gilded bronze closes the receptacle that contains the relics, which are themselves inclosed in a bag of Spanish leather, richly embossed. A copy of this last document was made and placed in the archives at Turin.

These papers, as selected by Columbus for preservation, were edited by Father Spotorno at Genoa, in 1823, in a volume called Codice diplomatico Colombo-Americano, and published by authority of the state. There [Pg 5] was an English edition at London, in 1823; and a Spanish at Havana, in 1867. Spotorno was reprinted, with additional matter, at Genoa, in 1857, as La Tavola di Bronzo, il pallio di seta, ed il Codice Colomboamericano, nuovamente illustrati per cura di Giuseppe Banchero.

THE GENOA CUSTODIA.

THE GENOA CUSTODIA.

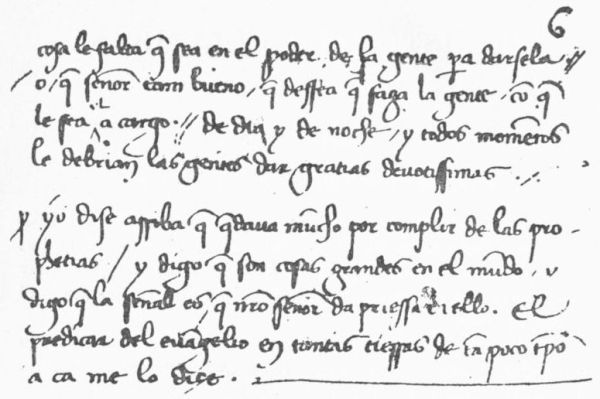

This Spotorno volume included two additional letters of Columbus, not yet mentioned, and addressed, March 21, 1502, and December 27, 1504, to Oderigo. They were found pasted in the duplicate copy of the papers given to Genoa, and are now preserved in a glass case, in the same custodia. A third letter, April 2, 1502, addressed to the governors of the bank of St. George, was omitted by Spotorno; but it is given by Harrisse in his Columbus and the Bank of Saint George (New York, 1888). This last was one of two letters, which Columbus sent, as he says, to the bank, but the other has not been found. The history of the one preserved is traced by Harrisse in the work last mentioned, and there are [Pg 6] lithographic and photographic reproductions of it. Harrisse's work just referred to was undertaken to prove the forgery of a manuscript which has within a few years been offered for sale, either as a duplicate of the one at Genoa, or as the original. When represented as the original, the one at Genoa is pronounced a facsimile of it. Harrisse seems to have proved the forgery of the one which is seeking a purchaser.

COLUMBUS'S LETTER, APRIL 2, 1502, ADDRESSED TO THE BANK OF ST.

GEORGE IN GENOA.

COLUMBUS'S LETTER, APRIL 2, 1502, ADDRESSED TO THE BANK OF ST.

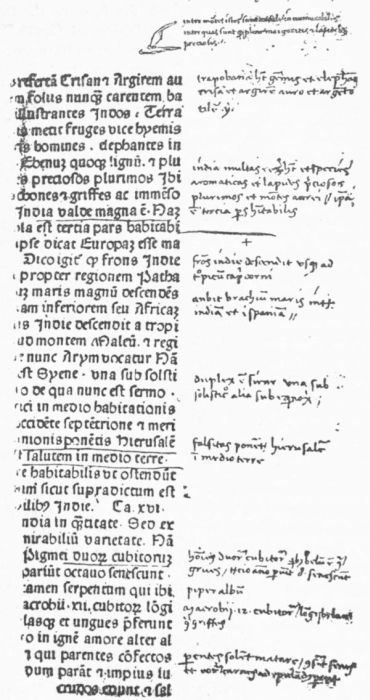

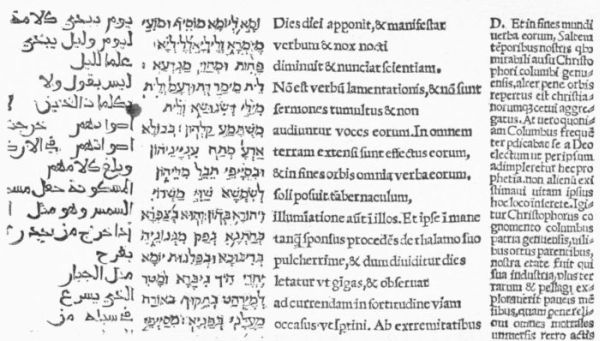

GEORGE IN GENOA.Some manuscript marginalia found in three different books, used by Columbus and preserved in the Biblioteca Colombina at Seville, are also remnants of the autographs of Columbus. These marginal notes are in copies of Æneas Sylvius's Historia Rerum ubique gestarum (Venice, 1477) of a Latin version of Marco Polo (Antwerp, 1485?), and of Pierre d'Ailly's De Imagine Mundi (perhaps 1490), though there is some suspicion that these last-mentioned notes may be those of Bartholomew, and not of Christopher, Columbus. These books have been particularly described in José Silverio Jorrin's Varios Autografos ineditos de Cristóbal Colon, published at Havana in 1888. In May, 1860, José Maria Fernandez y Velasco, the librarian of the Biblioteca Colombina, discovered a Latin text of the letter of Toscanelli, written by Columbus in this same copy of Æneas Sylvius. He believed it a Latin version of a letter originally written in Italian; but it was left for Harrisse to discover that the Latin was the original draft. A facsimile of this script is in Harrisse's Fernando Colon (Seville, 1871), and specimens of the marginalia were first given by Harrisse in his Notes on Columbus, whence they are reproduced in part in the Narrative and Critical History of America (vol. ii.).

It is understood that, under the auspices of the Italian government, Harrisse is now engaged in collating the texts and preparing a national memorial issue of the writings of Columbus, somewhat in accordance with a proposition which he made to the Minister of Public Instruction at Rome in his Le Quatrième Centenaire de la Découverte du Nouveau Monde (Genoa, 1887).

There are references to printed works of Columbus which I have not seen, as a Declaracion de Tabla Navigatoria, annexed to a treatise, Del Uso de la Carta de Navegar, by Dr. Grajales: a Tratado de las Cinco Zonas Habitables, which Humboldt found it very difficult to find.

ANNOTATIONS BY COLUMBUS ON THE IMAGO MUNDI.

ANNOTATIONS BY COLUMBUS ON THE IMAGO MUNDI.Of the manuscripts of Columbus which are lost, there are traces still to be discovered. One letter, which he dated off the Canaries, February 15, 1493, and which[Pg 9] must have contained some account of his first voyage, is only known to us from an intimation of Marino Sanuto that it was included in the Chronica Delphinea. It is probably from an imperfect copy of this last in the library at Brescia, that the letter in question was given in the book's third part (A. D. 1457-1500), which is now missing. We know also, from a letter still preserved (December 27, 1504), that there must be a letter somewhere, if not destroyed, sent by him respecting his fourth voyage, to Messer Gian Luigi Fieschi, as is supposed, the same who led the famous conspiracy against the house of Doria. Other letters, Columbus tells us, were sent at times to the Signora Madonna Catalina, who was in some way related to Fieschi.

In 1780, Francesco Pesaro, examining the papers of the Council of Ten, at Venice, read there a memoir of Columbus, setting forth his maritime project; or at least Pesaro was so understood by Marin, who gives the story at a later day in the seventh volume of his history of Venetian commerce. As Harrisse remarks, this paper, if it could be discovered, would prove the most interesting of all Columbian documents, since it would probably be found to fall within a period, from 1473 to 1487, when we have little or nothing authentic respecting Columbus's life. Indeed, it might happily elucidate a stage in the development of the Admiral's cosmographical views of which we know nothing.

We have the letter which Columbus addressed to Alexander VI., in February, 1502, as preserved in a copy made by his son Ferdinand; but no historical student has ever seen the Commentary, which he is said to have written after the manner of Cæsar, recounting the haps and mishaps of the first voyage, and which he is thought to have sent to the ruling Pontiff. This act of duty, if done after his return from his last voyage, must have been made to Julius the Second, not to Alexander.

Irving and others seem to have considered that this Cæsarian performance was in fact, the well-known journal of the first voyage; but there is a good deal of difficulty in identifying that which we only know in an abridged form, as made by Las Casas, with the narrative sent or intended to be sent to the Pope.

Ferdinand, or the writer of the Historie, later to be mentioned, [Pg 10] it seems clear, had Columbus's journal before him, though he excuses himself from quoting much from it, in order to avoid wearying the reader.

The original "journal" seems to have been in 1554 still in the possession of Luis Colon. It had not, accordingly, at that date been put among the treasures of the Biblioteca Colombina. Thus it may have fallen, with Luis's other papers, to his nephew and heir, Diego Colon y Pravia, who in 1578 entrusted them to Luis de Cardona. Here we lose sight of them.

Las Casas's abridgment in his own handwriting, however, has come down to us, and some entries in it would seem to indicate that Las Casas abridged a copy, and not the original. It was, up to 1886, in the library of the Duke of Orsuna, in Madrid, and was at that date bought by the Spanish government. While it was in the possession of Orsuna, it was printed by Varnhagen, in his Verdadera Guanahani (1864). It was clearly used by Las Casas in his own Historia, and was also in the hands of Ferdinand, when he wrote, or outlined, perhaps, what now passes for the life of his father, and Ferdinand's statements can sometimes correct or qualify the text in Las Casas. There is some reason to suppose that Herrera may have used the original. Las Casas tells us that in some parts, and particularly in describing the landfall and the events immediately succeeding, he did not vary the words of the original. This Las Casas abridgment was in the archives of the Duke del Infantado, when Navarrete discovered its importance, and edited it as early as 1791, though it was not given to the public till Navarrete published his Coleccion in 1825. When this journal is read, even as we have it, it is hard to imagine that Columbus could have intended so disjointed a performance to be an imitation of the method of Cæsar's Commentaries.

The American public was early given an opportunity to judge of this, and of its importance. It was by the instigation of George Ticknor that Samuel Kettell made a translation of the text as given by Navarrete, and published it in Boston in 1827, as a Personal Narrative of the first Voyage of Columbus to America, from a Manuscript recently discovered in Spain.

We also know that Columbus wrote other concise accounts of his discovery. On his return voyage, during a gale, on February 14, 1493, fearing his ship would founder, he prepared a statement on parchment, which was incased in wax, put in a barrel, and thrown overboard, to take the chance of washing ashore. A similar account, protected in like manner, he placed on his vessel's poop, to be washed off in case of disaster. Neither of these came, as far as is known, to the notice of anybody. They very likely simply duplicated the letters which he wrote on the voyage, intended to be dispatched to their destination on reaching port. The dates and places of these letters are not reconcilable with his journal. He was apparently approaching the Azores, when, on February 15, he dated a letter "off the Canaries," directed to Luis de Santangel. So false a record as "the Canaries" has never been satisfactorily explained. It may be imagined, perhaps, that the letter had been written when Columbus supposed he would make those islands instead of the Azores, and that the place of writing was not changed. It is quite enough, however, to rest satisfied with the fact that Columbus was always careless, and easily erred in such things, as Navarrete has shown. The postscript which is added is dated March 14, which seems hardly probable, or even possible, so that March 4 has been suggested. He professes to write it on the day of his entering the Tagus, and this was March 4. It is possible that he altered the date when he reached Palos, as is Major's opinion. Columbus calls this a second letter. Perhaps a former letter was the one which, as already stated, we have lost in the missing part of the Chronica Delphinea.

The original of this letter to Santangel, the treasurer of Aragon, and intended for the eyes of Ferdinand and Isabella, was in Spanish, and is known in what is thought to be a contemporary copy, found by Navarrete at Simancas; and it is printed by him in his Coleccion, and is given by Kettell in English, to make no other mention of places where it is accessible. Harrisse denies that this Simancas manuscript represents the original, as Navarrete had contended. A letter dated off the island of Santa Maria, the southernmost of the Azores, three days after the letter to Santangel, February 18, essentially the same, and addressed to Gabriel Sanchez, was found in what seemed to be an early copy, among the papers of the Colegio Mayor de Cuenca. This text was [Pg 12] printed by Varnhagen at Valencia, in 1858, as Primera Epistola del Almirante Don Cristóbal Colon, and it is claimed by him that it probably much more nearly represents the original of Columbus's own drafting.

There was placed in 1852 in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana at Milan, from the library of Baron Pietro Custodi, a printed edition of this Spanish letter, issued in 1493, perhaps somewhere in Spain or Portugal, for Barcelona and Lisbon have been named. Harrisse conjectures that Sanchez gave his copy to some printer in Barcelona. Others have contended that it was not printed in Spain at all. No other copy of this edition has ever been discovered. It was edited by Cesare Correnti at Milan in 1863, in a volume called Lettere autografe di Cristoforo Colombo, nuovamente stampate, and was again issued in facsimile in 1866 at Milan, under the care of Girolamo d'Adda, as Lettera in lingua Spagnuola diretta da Cristoforo Colombo a Luis de Sant-Angel. Major and Becher, among others, have given versions of it to the English reader, and Harrisse gives it side by side with a French version in his Christophe Colomb (i. 420), and with an English one in his Notes on Columbus.

This text in Spanish print had been thought the only avenue of approach to the actual manuscript draft of Columbus, till very recently two other editions, slightly varying, are said to have been discovered, one or both of which are held by some, but on no satisfactory showing, to have preceded in issue, probably by a short interval, the Ambrosian copy.

One of these newly alleged editions is on four leaves in quarto, and represents the letter as dated on February 15 and March 14, and its cut of type has been held to be evidence of having been printed at Burgos, or possibly at Salamanca. That this and the Ambrosian letter were printed one from the other, or independently from some unknown anterior edition, has been held to be clear from the fact that they correspond throughout in the division of lines and pages. It is not easily determined which was the earlier of the two, since there are errors in each corrected in the other. This unique four-leaf quarto was a few months since offered for sale in London, by Ellis and Elvey, who have published (1889) an English translation of it, with annotations by Julia E. S. Rae. It is now understood to be in [Pg 13] the possession of a New York collector. It is but fair to say that suspicions of its genuineness have been entertained; indeed, there can be scarce a doubt that it is a modern fabrication.

The other of these newly discovered editions is in folio of two leaves, and was the last discovered, and was very recently held by Maisonneuve of Paris at 65,000 francs, and has since been offered by Quaritch in London for £1,600. It is said to have been discovered in Spain, and to have been printed at Barcelona; and this last fact is thought to be apparent from the Catalan form of some of the Spanish, which has disappeared in the Ambrosian text. It also gives the dates February 15 and March 14. A facsimile edition has been issued under the title La Lettre de Christophe Colomb, annonçant la Découverte du Nouveau Monde.

Caleb Cushing, in the North American Review in October, 1825, refers to newspaper stories then current of a recent sale of a copy of the Spanish text in London, for £33 12s. to the Duke of Buckingham. It cannot now be traced.

Harrisse finds in Ferdinand's catalogue of the Biblioteca Colombina what was probably a Catalan text of this Spanish letter; but it has disappeared from the collection.

Bergenroth found at Simancas, some years ago, the text of another letter by Columbus, with the identical dates already given, and addressed to a friend; but it conveyed nothing not known in the printed Spanish texts. He, however, gave a full abstract of it in the Calendar of State Papers relating to England and Spain.

Columbus is known, after his return from the second voyage, to have been the guest of Andrès Bernaldez, the Cura de los Palacios, and he is also known to have placed papers in this friend's hands; and so it has been held probable by Muñoz that another Spanish text of Columbus's first account is embodied in Bernaldez's Historia de los Reyes Católicos. The manuscript of this work, which gives thirteen chapters to Columbus, long remained unprinted in the royal library at Madrid, and Irving, Prescott, and Humboldt all used it in that form. It was finally printed at Granada in 1856, as edited by Miguel Lafuente y Alcántara, and was reprinted at Seville in 1870. Harrisse, in his Notes on Columbus, gives an English version of this section on the Columbus voyage.

These, then, are all the varieties of the Spanish text of Columbus's first announcement of his discovery which are at present known. When the Ambrosian text was thought to be the only printed form of it, Varnhagen, in his Carta de Cristóbal Colon enviada de Lisboa á Barcelona en Marzo de 1493 (Vienna, 1869; and Paris, 1870), collated the different texts to try to reconstruct a possible original text, as Columbus wrote it. In the opinion of Major no one of these texts can be considered an accurate transcript of the original.

There is a difference of opinion among these critics as to the origin of the Latin text which scholars generally cite as this first letter of Columbus. Major thinks this Latin text was not taken from the Spanish, though similar to it; while Varnhagen thinks that the particular Spanish text found in the Colegio Mayor de Cuenca was the original of the Latin version.

There is nothing more striking in the history of the years immediately following the discovery of America than the transient character of the fame which Columbus acquired by it. It was another and later generation that fixed his name in the world's regard.

Harrisse points out how some of the standard chroniclers of the world's history, like Ferrebouc, Regnault, Galliot du Pré, and Fabian, failed during the early half of the sixteenth century to make any note of the acts of Columbus; and he could find no earlier mention among the German chroniclers than that of Heinrich Steinhowel, some time after 1531. There was even great reticence among the chroniclers of the Low Countries; and in England we need to look into the dispatches sent thence by the Spanish ambassadors to find the merest mention of Columbus so early as 1498. Perhaps the reference to him made eleven years later (1509), in an English version of Brandt's Shyppe of Fools, and another still ten years later in a little native comedy called The New Interlude, may have been not wholly unintelligible. It was not till about 1550 that, so far as England is concerned, Columbus really became a historical character, in Edward Hall's Chronicle.

Speaking of the fewness of the autographs of Columbus [Pg 15] which are preserved, Harrisse adds: "The fact is that Columbus was very far from being in his lifetime the important personage he now is; and his writings, which then commanded neither respect nor attention, were probably thrown into the waste-basket as soon as received."

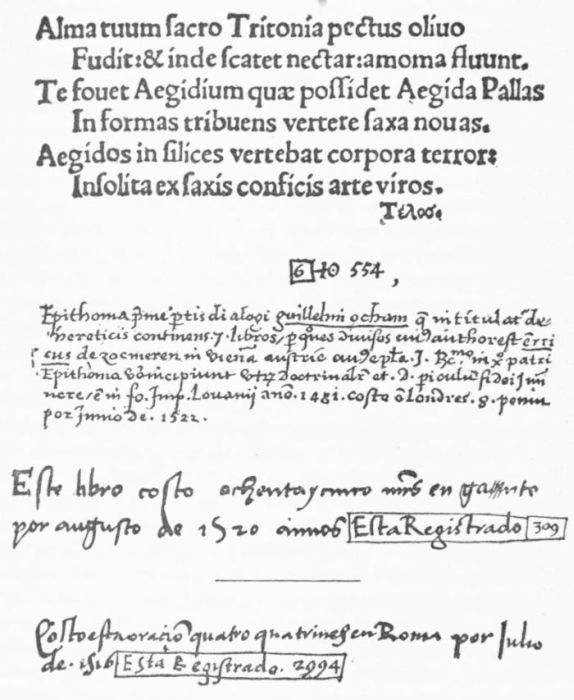

Nevertheless, substantial proof seems to exist in the several editions of the Latin version of this first letter, which were issued in the months immediately following the return of Columbus from his first voyage, as well as in the popular versification of its text by Dati in two editions, both in October, 1493, besides another at Florence in 1495, to show that for a brief interval, at least, the news was more or less engrossing to the public mind in certain confined areas of Europe. Before the discovery of the printed editions of the Spanish text, there existed an impression that either the interest in Spain was less than in Italy, or some effort was made by the Spanish government to prevent a wide dissemination of the details of the news.

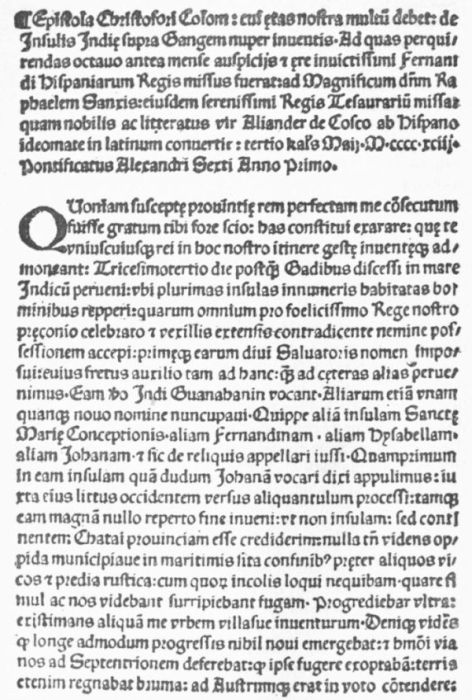

The two Genoese ambassadors who left Barcelona some time after the return of Columbus, perhaps in August, 1493, may possibly have taken to Italy with them some Spanish edition of the letter. The news, however, had in some form reached Rome in season to be the subject of a papal bull on May 3d. We know that Aliander or Leander de Cosco, who made the Latin version, very likely from the Sanchez copy, finished it probably at Barcelona, on the 29th of April, not on the 25th as is sometimes said. Cosco sent it at once to Rome to be printed, and his manuscript possibly conveyed the first tidings, to Italy,—such is Harrisse's theory,—where it reached first the hands of the Bishop of Monte Peloso, who added to it a Latin epigram. It was he who is supposed to have committed it to the printer in Rome, and in that city, during the rest of 1493, four editions at least of Cosco's Latin appeared. Two of these editions are supposed to be printed by Plannck, a famous Roman printer; one is known to have come from the press of Franck Silber. All but one were little quartos, of the familiar old style, of three or four black-letter leaves; while the exception was a small octavo with woodcuts. It is Harrisse's opinion that this pictorial edition was really printed at Basle. In Paris, during the same time or shortly after, there were three editions of a similar appearance, [Pg 16] all from one press. The latest of all, brought to light but recently, seems to have been printed by a distinguished Flemish printer, Thierry Martens, probably at Antwerp. It is not improbable that other editions printed in all these or other cities may yet be found. It is noteworthy that nothing was issued in Germany, as far as we know, before a German version of the letter appeared at Strassburg in 1497.

FIRST PAGE, COLUMBUS'S FIRST LETTER, LATIN EDITION, 1493.

FIRST PAGE, COLUMBUS'S FIRST LETTER, LATIN EDITION, 1493.The text in all these Latin editions is intended to be the same. But a very few copies of any edition, and only a single copy of two or three of them, are known. The Lenox, the Carter-Brown, and the Ives libraries in this country are the chief ones possessing any of them, and the collections of the late Henry C. Murphy and Samuel L. M. Barlow also possessed a copy or two, the edition owned by Barlow passing in February, 1890, to the Boston Public Library. This scarcity and the rivalry of collectors would probably, in case any one of them should be brought upon the market, raise the price to fifteen hundred dollars or more. The student is not so restricted as this might imply, for in several cases there have been modern facsimiles and reprints, and there is an early reprint by Veradus, annexed to his poem (1494) on the capture of Granada. The text usually quoted by the older writers, however, is that embodied in the Bellum Christianorum Principum of Robertus Monarchus (Basle, 1533).

In these original small quartos and octavos, there is just enough uncertainty and obscurity as to dates and printers, to lure bibliographers and critics of typography into research and controversy; and hardly any two of them agree in assigning the same order of publication to these several issues. The present writer has in the second volume of the Narrative and Critical History of America grouped the varied views, so far as they had in 1885 been made known. The bibliography to which Harrisse refers as being at the end of his work on Columbus was crowded out of its place and has not appeared; but he enters into a long examination of the question of priority in the second chapter of his last volume. The earliest English translation of this Latin text appeared in the Edinburgh Review in 1816, and other issues have been variously made since that date.

We get some details of this first voyage in Oviedo, which we do not find in the journal, and Vicente Yañez Pinzon and Hernan Perez Matheos, who were companions of Columbus, are said to be the source of this additional matter. The testimony in the lawsuit of 1515, particularly that of Garcia Hernandez, who was in the "Pinta," and of a sailor named Francisco Garcia Vallejo, adds other details.

There is no existing account by Columbus himself of his experiences during his second voyage, and of that cruise along the Cuban coast in which he supposed himself to have come in sight of the Golden Chersonesus. The Historie tells us that during this cruise he kept a journal, Libro del Segundo Viage, till he was prostrated by sickness, and this itinerary is cited both in the Historie and by Las Casas. We also get at second-hand from Columbus, what was derived from him in conversation after his return to Spain, in the account of these explorations which Bernaldez has embodied in his Reyes Católicos. Irving says that he found these descriptions of Bernaldez by far the most useful of the sources for this period, as giving him the details for a picturesque narrative. On disembarking at Cadiz in June, 1495, Columbus sent to his sovereigns two dispatches, neither of which is now known.

It was in the collection of the Duke of Veragua that Navarrete discovered fifteen autograph letters of Columbus, four of them addressed to his friend, the Father Gaspar Gorricio, and the rest to his son Diego. Navarrete speaks of them when found as in a very deplorable and in parts almost unreadable condition, and severely taxing, for deciphering them, the practiced skill of Tomas Gonzalez, which had been acquired in the care which he had bestowed on the archives of Simancas. It is known that two letters addressed to Gorricio in 1498, and four in 1501, beside a single letter addressed in the last year to Diego Colon, which were in the iron chest at Las Cuevas, are not now in the archives of the Duke of Veragua; and it is further known that during the great lawsuit of Columbus's heirs, Cristoval de Cardona tampered with that chest, and was brought to account for the act in 1580. Whatever he removed may possibly some day be found, as Harrisse thinks, among the notarial records of Valencia.

Two letters of Columbus respecting his third voyage are only known in early copies; one in Las Casas's hand belonged to the Duke of Orsuna, and the other addressed to the nurse of Prince Juan is in the Custodia collection at Genoa. Both are printed by Navarrete.

Columbus, in a letter dated December 27, 1504, mentions a relation of his fourth voyage with a supplement, which he had sent from Seville to Oderigo; but it is not known. We are without trace also of other letters, which he wrote at Dominica and at other points during this voyage. We do know, however, a letter addressed by Columbus to Ferdinand and Isabella, giving some account of his voyage to July 7, 1503. The lost Spanish original is represented in an early copy, which is printed by Navarrete. Though no contemporary Spanish edition is known, an Italian version was issued at Venice in 1505, as Copia de la Lettera per Colombo mandata. This was reprinted with comments by Morelli, at Bassano, in 1810, and the title which this librarian gave it of Lettera Rarissima has clung to it, in most of the citations which refer to it.

Peter Martyr, writing in January, 1494, mentions just having received a letter from Columbus, but it is not known to exist.

Las Casas is said to have once possessed a treatise by Columbus on the information obtained from Portuguese and Spanish pilots, concerning western lands; and he also refers to Libros de Memorias del Almirante. He is also known by his own statements to have had numerous autograph letters of Columbus. What has become of them is not known. If they were left in the monastery of San Gregorio at Valladolid, where Las Casas used them, they have disappeared with papers of the convent, since they were not among the archives of the suppressed convents, as Harrisse tells us, which were entrusted in 1850 to the Academy of History at Madrid.

In his letter to Doña Juana, Columbus says that he has deposited a work in the Convent de la Mejorada, in which he has predicted the discovery of the Arctic pole. It has not been found.

Harrisse also tells us of the unsuccessful search which he has made for an alleged letter of Columbus, said in Gunther and Schultz's handbook of autographs (Leipzig, 1856) to have been bought in England by the Duke of Buckingham; and it was learned from Tross, the Paris bookseller, that about 1850 some autograph letters of Columbus, seen by him, were sent to England for sale.

After his return from his first voyage, Columbus prepared a map and an accompanying table of longitudes and latitudes for the new discoveries. They are known to have been the subject of correspondence between him and the queen.

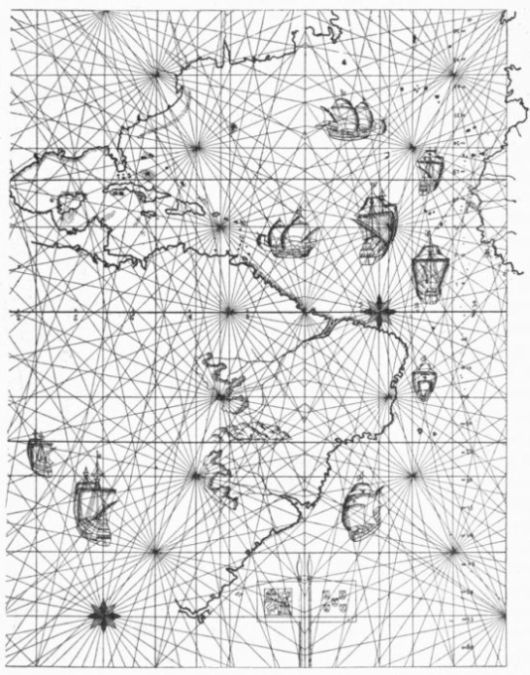

There are various other references to maps which Columbus had constructed, to embody his views or show his discoveries. Not one, certainly to be attributed to him, is known, though Ojeda, Niño, and others are recorded as having used, in their explorations, maps made by Columbus. Peter Martyr's language does not indicate that Columbus ever completed any chart, though he had, with the help of his brother Bartholomew, begun one. The map in the Ptolemy of 1513 is said by Santarem to have been drawn by Columbus, or to have been based on his memoranda, but the explanation on the map seems rather to imply that information derived from an admiral in the service of Portugal was used in correcting it, and since Harrisse has brought to light what is usually called the Cantino map, there is strong ground for supposing that the two had one prototype.

Let us pass from records by Columbus to those about him. We owe to an ancient custom of Italy that so much has been preserved, to throw in the aggregate no small amount of light on the domestic life of the family in which Columbus was the oldest born. During the fourteen years in which his father lived at Savona, every little business act and legal transaction was attested before notaries, whose records have been preserved filed in filzas in the archives of the town.

These filzas were simply a file of documents tied together by a string passed through each, and a filza generally embraced a year's accumulation. The photographic facsimile which Harrisse gives in his Columbus and the Bank of Saint George, of the letter of Columbus preserved by the bank, shows how the sheet was folded once lengthwise, and then the hole was made midway in each fold.

We learn in this way that, as early as 1470 and later, Columbus stood security for his father. We find him in 1472 the witness of another's will. As under the Justinian procedure [Pg 21] the notary's declaration sufficed, such documents in Italy are not rendered additionally interesting by the autograph of the witness, as they would be in England. This notarial resource is no new discovery. As early as 1602, thirteen documents drawn from similar depositaries were printed at Genoa, in some annotations by Giulio Salinerio upon Cornelius Tacitus. Other similar papers were discovered by the archivists of Savona, Gian Tommaso and Giambattista Belloro, in 1810 (reprinted, 1821) and 1839 respectively, and proving the general correctness of the earlier accounts of Columbus's younger days given in Gallo, Senarega, and Giustiniani. It is to be regretted that the original entries of some of these notarial acts are not now to be found, but patient search may yet discover them, and even do something more to elucidate the life of the Columbus family in Savona.

There has been brought into prominence and published lately a memoir of the illustrious natives of Savona, written by a lawyer, Giovanni Vincenzo Verzellino, who died in that town in 1638. This document was printed at Savona in 1885, under the editorial care of Andrea Astengo; but Harrisse has given greater currency to its elucidations for our purpose in his Christophe Colomb et Savone (Genoa, 1877).

Harrisse is not unwisely confident that the nineteen documents—if no more have been added—throwing light on minor points of the obscure parts of the life of Columbus and his kindred, which during recent years have been discovered in the notarial files of Genoa by the Marquis Marcello Staglieno, may be only the precursors of others yet to be unearthed, and that the pages of the Giornale Ligustico may continue to record such discoveries as it has in the past.

The records of the Bank of Saint George in Genoa have yielded something, but not much. In the state archives of Genoa, preserved since 1817 in the Palazzetto, we might hope to find some report of the great discovery, of which the Genoese ambassadors, Francesco Marchesio and Gian Antonio Grimaldi, were informed, just as they were taking leave of Ferdinand and Isabella for returning to Italy; but nothing of that kind has yet been brought to light there; nor was it ever there, unless the account which Senarega gives in the [Pg 22] narrative printed in Muratori was borrowed thence. We may hope, but probably in vain, to have these public archives determine if Columbus really offered to serve his native country in a voyage of discovery. The inquirer is more fortunate if he explores what there is left of the archives of the old abbey of St. Stephen, which, since the suppression of the convents in 1797, have been a part of the public papers, for he can find in them some help in solving some pertinent questions.

Harrisse tells us in 1887 that he had been waiting two years for permission to search the archives of the Vatican. What may yet be revealed in that repository, the world waits anxiously to learn. It may be that some one shall yet discover there the communication in which Ferdinand and Isabella announced to the Pope the consummation of the hopes of Columbus. It may be that the diplomatic correspondence covering the claims of Spain by virtue of the discovery of Columbus, and leading to the bull of demarcation of May, 1493, may yet be found, accompanied by maps, of the highest interest in interpreting the relations of the new geography. There is no assurance that the end of manuscript disclosures has yet come. Some new bit of documentary proof has been found at times in places quite unexpected. The number of Italian observers in those days of maritime excitement living in the seaports and trading places of Spain and Portugal, kept their home friends alert in expectation by reason of such appetizing news. Such are the letters sent to Italy by Hanibal Januarius, and by Luca, the Florentine engineer, concerning the first voyage. There are similar transient summaries of the second voyage. Some have been found in the papers of Macchiavelli, and others had been arranged by Zorzi for a new edition of his documentary collection. These have all been recovered of recent years, and Harrisse himself, Gargiolli, Guerrini, and others, have been instrumental in their publication.

It was thirty-seven years after the death of Columbus before, under an order of Charles the Fifth, February 19, 1543, the archives of Spain were placed in some sort of order and security at Simancas. The great masses of papers filed by the crown secretaries and the Councils of the Indies and of Seville, were gradually gathered there, but not until many had been lost. Others apparently disappeared at a later day, for we are now aware that many to which Herrera refers cannot be found. New efforts to secure the preservation and systematize the accumulation of manuscripts were made by order of Philip the Second in 1567, but it would seem without all the success that might have been desired. Towards the end of the last century, it was the wish of Charles the Third that all the public papers relating to the New World should be selected from Simancas and all other places of deposit and carried to Seville. The act was accomplished in 1788, when they were placed in a new building which had been provided for them. Thus it is that to-day the student of Columbus must rather search Seville than Simancas for new documents, though a few papers of some interest in connection with the contests of his heirs with the crown of Castile may still exist at Simancas. Thirty years ago, if not now, as Bergenroth tells us, there was little comfort for the student of history in working at Simancas. The papers are preserved in an old castle, formerly belonging to the admirals of Castile, which had been confiscated and devoted to the uses of such a repository. The one large room which was assigned for the accommodation of readers had a northern aspect, and as no fires were allowed, the note-taker found not infrequently in winter the ink partially congealed in his pen. There was no imaginable warmth even in the landscape as seen from the windows, since, amid a treeless waste, the whistle of cold blasts in winter and a blinding African heat in summer characterize the climate of this part of Old Castile.

Of the early career of Columbus, it is very certain that something may be gained at Simancas, for when Bergenroth, sent by the English government, made search there to illustrate the relations of Spain with England, and published his results, with the assistance of Gayangos, in 1862-1879, as a Calendar of Letters, Despatches, and State Papers relating to Negotiations between England and Spain, one of the earliest entries of his first printed volume, under 1485, was a complaint of Ferdinand and Isabella against a Columbus—some have supposed it our Christopher—for his participancy in the piratical service of the French.

ARCHIVO DE SIMANCAS.

ARCHIVO DE SIMANCAS.Harrisse complains that we have as yet but scant knowledge of what the archives of the Indies at Seville may contain, but they probably throw light rather upon the successors of Columbus than upon the career of the Admiral himself.

The notarial archives of Seville are of recent construction, the gathering of scattered material having been first ordered so late as 1869. The partial examination which has since been made of them has revealed some slight evidences of the life of some of Columbus's kindred, and it is quite possible some future inquirer will be rewarded for his diligent search among them.

It is also not unlikely that something of interest may be brought to light respecting the descendants of Columbus who have lived in Seville, like the Counts of Gelves; but little can be expected regarding the life of the Admiral himself.

The personal fame of Columbus is much more intimately connected with the monastery of Santa Maria de las Cuevas. Here his remains were transported in 1509; and at a later time, his brother and son, each Diego by name, were laid beside him, as was his grandson Luis. Here in an iron chest the family muniments and jewels were kept, as has been said. It is affirmed that all the documents which might have grown out of these transactions of duty and precaution, and which might incidentally have yielded some biographical information, are nowhere to be found in the records of the monastery. A century ago or so, when Muñoz was working in these records, there seems to have been enough to repay his exertions, as we know by his citations made between 1781 and 1792.

The national archives of the Torre do Tombo, at Lisbon, begun so far back as 1390, are well known to have been explored by Santarem, then their keeper, primarily for traces of the career of Vespucius; but so intelligent an antiquary could not have forgotten, as a secondary aim, the acts of Columbus. The search yielded him, however, nothing in this last direction; nor was Varnhagen more fortunate. Harrisse had hopes to discover there the correspondence of Columbus with John the Second, in 1488; but the[Pg 26] search was futile in this respect, though it yielded not a little respecting the Perestrello family, out of which Columbus took his wife, the mother of the heir of his titles. There is even hope that the notarial acts of Lisbon might serve a similar purpose to those which have been so fruitful in Genoa and Savona. There are documents of great interest which may be yet obscurely hidden away, somewhere in Portugal, like the letter from the mouth of the Tagus, which Columbus on his return in March, 1493, addressed to the Portuguese king, and the diplomatic correspondence of John the Second and Ferdinand of Aragon, which the project of a second voyage occasioned, as well as the preliminaries of the treaty of Tordesillas.

There may be yet some hope from the archives of Santo Domingo itself, and from those of its Cathedral, to trace in some of their lines the descendants of the Admiral through his son Diego. The mishaps of nature and war have, however, much impaired the records. Of Columbus himself there is scarce a chance to learn anything here. The papers of the famous lawsuit of Diego Colon with the crown seem to have escaped the attention of all the historians before the time of Muñoz and Navarrete. The direct line of male descendants of the Admiral ended in 1578, when his great-grandson, Diego Colon y Pravia, died on the 27th January, a childless man. Then began another contest for the heritage and titles, and it lasted for thirty years, till in 1608 the Council of the Indies judged the rights to descend by a turn back to Diego's aunt Isabel, and thence to her grandson, Nuño de Portugallo, Count of Gelves. The excluded heirs, represented by the children of a sister of Diego, Francisca, who had married Diego Ortegon, were naturally not content; and out of the contest which followed we get a large mass of printed statements and counter statements, which used with caution, offer a study perhaps of some of the transmitted traits of Columbus. Harrisse names and describes nineteen of these documentary memorials, the last of which bears date in 1792. The most important of them all, however, is one printed at Madrid in 1606, known as Memorial del Pleyto, in which we find the descent of the true and spurious lines, and learn something too much of the scandalous life of Luis, the grandson of the Admiral, to say nothing of the[Pg 27] illegitimate taints of various other branches. Harrisse finds assistance in working out some of the lines of the Admiral's descendants, in Antonio Caetano de Sousa's Historia Genealogica da Casa Real Portugueza (Lisbon, 1735-49, in 14 vols.).

The most important collection of documents gathered by individual efforts in Spain, to illustrate the early history of the New World, was that made by Juan Bautista Muñoz, in pursuance of royal orders issued to him in 1781 and 1788, to examine all Spanish archives, for the purpose of collecting material for a comprehensive History of the Indies. Muñoz has given in the introduction of his history a clear statement of the condition of the different depositories of archives in Spain, as he found them towards the end of the last century, when a royal order opened them all to his search. A first volume of Muñoz's elaborate and judicious work was issued in 1793, and Muñoz died in 1799, without venturing on a second volume to carry the story beyond 1500, where he had left it. He was attacked for his views, and there was more or less of a pamphlet war over the book before death took him from the strife; but he left a fragment of the second volume in manuscript, and of this there is a copy in the Lenox Library in New York. Another copy was sold in the Brinley sale. The Muñoz collection of copies came in part, at least, at some time after the collector's death into the hands of Antonio de Uguina, who placed them at the disposal of Irving; and Ternaux seems also to have used them. They were finally deposited by the Spanish government in the Academy of History at Madrid. Here Alfred Demersey saw them in 1862-63, and described them in the Bulletin of the French Geographical Society in June, 1864, and it is on this description as well as on one in Fuster's Biblioteca Valenciana, that Harrisse depends, not having himself examined the documents.

Martin Fernandez de Navarrete was guided in his career as a collector of documents, when Charles the Fourth made an order, October 15, 1789, that there should be such a work begun to constitute the nucleus of a library and museum. The troublous times which succeeded interrupted the work, and it was not till 1825 that Navarrete brought out the first volume of his Coleccion de los Viages y Descubrimientos que hicieron por Mar los Españoles desde [Pg 28] Fines del Siglo XV., a publication which a fifth volume completed in 1837, when he was over seventy years of age.

Any life of Columbus written from documentary sources must reflect much light from this collection of Navarrete, of which the first two volumes are entirely given to the career of the Admiral, and indeed bear the distinctive title of Relaciones, Cartas y otros Documentos, relating to him.

Navarrete was engaged thirty years on his work in the archives of Spain, and was aided part of the time by Muñoz the historian, and by Gonzales the keeper of the archives at Simancas. His researches extended to all the public repositories, and to such private ones as could be thought to illustrate the period of discovery. Navarrete has told the story of his searches in the various archives of Spain, in the introduction to his Coleccion, and how it was while searching for the evidences of the alleged voyage of Maldonado on the Pacific coast of North America, in 1588, that he stumbled upon Las Casas's copies of the relations of Columbus, for his first and third voyages, then hid away in the archives of the Duc del Infantado; and he was happy to have first brought them to the attention of Muñoz.

There are some advantages for the student in the use of the French edition of Navarrete's Relations des Quatre Voyages entrepris par Colomb, since the version was revised by Navarrete himself, and it is elucidated, not so much as one would wish, with notes by Rémusat, Balbi, Cuvier, Jomard, Letronne, St. Martin, Walckenaer, and others. It was published at Paris in three volumes in 1828. The work contains Navarrete's accounts of Spanish pre-Columbian voyages, of the later literature on Columbus, and of the voyages of discovery made by other efforts of the Spaniards, beside the documentary material respecting Columbus and his voyages, the result of his continued labors. Caleb Cushing, in his Reminiscences of Spain in 1833, while commending the general purposes of Navarrete, complains of his attempts to divert the indignation of posterity from the selfish conduct of Ferdinand, and to vindicate him from the charge of injustice towards Columbus. This plea does not find to-day the same sympathy in students that it did sixty years ago.

Father Antonio de Aspa of the monastery of the Mejorada, formed a collection of documents relating to the discovery of the New World, and it was in this collection, now preserved in the Academy of History at Madrid, that Navarrete discovered that curious narration of the second voyage of Columbus by Dr. Chanca, which had been sent to the chapter of the Cathedral, and which Navarrete included in his collection. It is thought that Bernaldez had used this Chanca narrative in his Reyes Católicos.

Navarrete's name is also connected, as one of its editors, with the extensive Coleccion de Documentos Ineditos para la Historia de España, the publication of which was begun in Madrid in 1847, two years before Navarrete's death. This collection yields something in elucidation of the story to be here told; but not much, except that in it, at a late day, the Historia of Las Casas was first printed.

In 1864, there was still another series begun at Madrid, Coleccion de Documentos Ineditos relativos al Descubrimiento, Conquista y Colonizacion de las Posesiones Españolas en América y Oceania, under the editing of Joaquin Pacheco and Francisco de Cárdenas, who have not always satisfied students by the way in which they have done their work. Beyond the papers which Navarrete had earlier given, and which are here reprinted, there is not much in this collection to repay the student of Columbus, except some long accounts of the Repartimiento in Española.

The latest documentary contribution is the large folio, with an appendix of facsimile writings of Columbus, Vespucius, and others, published at Madrid in 1877, by the government, and called Cartas de Indias, in which it has been hinted some use has been made of the matter accumulated by Navarrete for additional volumes of his Coleccion.

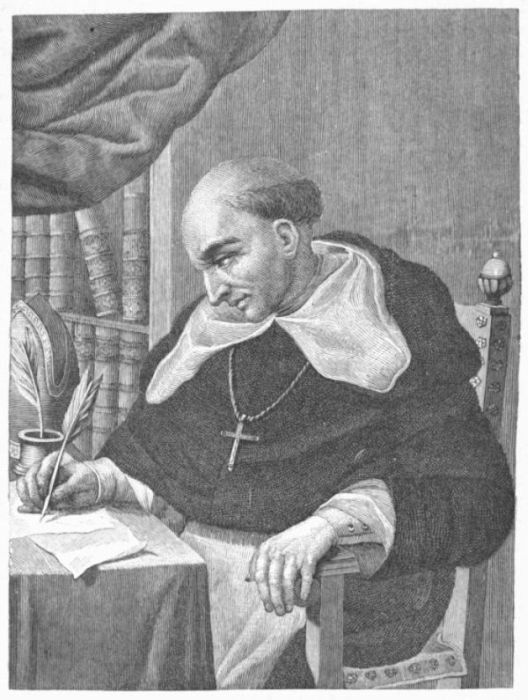

PART OF A PAGE IN THE GIUSTINIANI PSALTER, SHOWING THE BEGINNING OF THE EARLIEST PRINTED LIFE OF COLUMBUS.

PART OF A PAGE IN THE GIUSTINIANI PSALTER, SHOWING THE BEGINNING OF THE EARLIEST PRINTED LIFE OF COLUMBUS.We may most readily divide by the nationalities of the writers our enumeration of those who have used the material which has been considered in the previous chapter. We begin, naturally, with the Italians, the countrymen of Columbus. We may look first to three Genoese, and it has been shown that while they used documents apparently now lost, they took nothing from them which we cannot get from other sources; and they all borrowed from common originals, or from each other. Two of these writers are Antonio Gallo, the official chronicler of the Genoese Republic, on the first and second voyages of Columbus, and so presumably writing before the third was made, and Bartholomew Senarega on the affairs of Genoa, both of which recitals were published by Muratori, in his great Italian collection. The third is Giustiniani, the Bishop of Nebbio, who, publishing in 1516, at Genoa, a polyglot Psalter, added, as one of his elucidations of the nineteenth psalm, on the plea that Columbus had often boasted he was chosen to fulfill its prophecy, a brief life of Columbus, in which the story of the humble origin of the navigator has in the past been supposed to have first been told. The other accounts, it now appears, had given that condition an equal prominence. Giustiniani was but a child when Columbus left Genoa, and could not have known him; and taking, very likely, much from hearsay, he might have made some errors, which were repeated or only partly corrected in his Annals of Genoa, published in 1537, the year following his own death. It is not found, however, that the sketch is in any essential particular far from correct, and it has been confirmed by recent investigations. The English of it is given in Harrisse's Notes on Columbus (pp. 74-79). The statements of the Psalter respecting Columbus were reckoned with other things so false that the Senate of[Pg 32] Genoa prohibited its perusal and allowed no one to possess it,—at least so it is claimed in the Historie of 1571; but no one has ever found such a decree, nor is it mentioned by any who would have been likely to revert to it, had it ever existed.

The account in the Collectanea of Battista Fulgoso (sometimes written Fregoso), printed at Milan in 1509, is of scarcely any original value, though of interest as the work of another Genoese. Allegetto degli Allegetti, whose Ephemerides is also published in Muratori, deserves scarcely more credit, though he seems to have got his information from the letters of Italian merchants living in Spain, who communicated current news to their home correspondents. Bergomas, who had published a chronicle as early as 1483, made additions to his work from time to time, and in an edition printed at Venice, in 1503, he paraphrased Columbus's own account of his first voyage, which was reprinted in the subsequent edition of 1506. In this latter year Maffei de Volterra published a commentary at Rome, of much the same importance. Such was the filtering process by which Italy, through her own writers, acquired contemporary knowledge of her adventurous son.

The method was scarcely improved in the condensation of Jovius (1551), or in the traveler's tales of Benzoni (1565).

Harrisse affirms that it is not till we come down to the Annals of Genoa, published by Filippo Casoni, in 1708, that we get any new material in an Italian writer, and on a few points this last writer has adduced documentary evidence, not earlier made known. It is only when we pass into the present century that we find any of the countrymen of Columbus undertaking in a sustained way to tell the whole story of Columbus's life. Léon had noted that at some time in Spain, without giving place and date, Columbus had printed a little tract, Declaration de Tabla Navigatoria; but no one before Luigi Bossi had undertaken to investigate the writings of Columbus. He is precursor of all the modern biographers of Columbus, and his book was published at Milan, in 1818. He claimed in his appendix to have added rare and unpublished documents, but Harrisse points out how they had all been printed earlier.

Bossi expresses opinions respecting the Spanish nation that are by no means acceptable to that people, and Navarrete not[Pg 33] infrequently takes the Italian writer to task for this as for his many errors of statement, and for the confidence which he places even in the pictorial designs of De Bry as historical records.

There is nothing more striking in the history of American discovery than the fact that the Italian people furnished to Spain Columbus, to England Cabot, and to France Verrazano; and that the three leading powers of Europe, following as maritime explorers in the lead of Portugal, who could not dispense with Vespucius, another Italian, pushed their rights through men whom they had borrowed from the central region of the Mediterranean, while Italy in its own name never possessed a rood of American soil. The adopted country of each of these Italians gave more or less of its own impress to its foster child. No one of these men was so impressible as Columbus, and no country so much as Spain was likely at this time to exercise an influence on the character of an alien. Humboldt has remarked that Columbus got his theological fervor in Andalusia and Granada, and we can scarcely imagine Columbus in the garb of a Franciscan walking the streets of free and commercial Genoa as he did those of Seville, when he returned from his second voyage.

The latest of the considerable popular Italian lives of Columbus is G. B. Lemoyne's Colombo e la Scoperta dell' America, issued at Turin, in 1873.

We may pass now to the historians of that country to which Columbus betook himself on leaving Italy; but about all to be found at first hand is in the chronicle of João II. of Portugal, as prepared by Ruy de Pina, the archivist of the Torre do Tombo. At the time of the voyage of Columbus Ruy was over fifty, while Garcia de Resende was a young man then living at the Portuguese court, who in his Choronica, published in 1596, did little more than borrow from his elder, Ruy; and Resende in turn furnished to João de Barros the staple of the latter's narrative in his Decada da Asia, printed at Lisbon, in 1752.

We find more of value when we summon the Spanish writers. Although Peter Martyr d'Anghiera was an Italian, Muñoz reckons him a Spaniard, since he was naturalized in Spain. He was a man of thirty years, when, coming from Rome, he settled in Spain, a few years before Columbus attracted much notice. Martyr had been borne thither on a reputation of his own, which had commended his busy young nature to the attention of the Spanish court. He took orders and entered upon a prosperous career, proceeding by steps, which successively made him the chaplain of Queen Isabella, a prior of the Cathedral of Granada, and ultimately the official chronicler of the Indies. Very soon after his arrival in Spain, he had disclosed a quick eye for the changeful life about him, and he began in 1488 the writing of those letters which, to the number of over eight hundred, exist to attest his active interest in the events of his day. These events he continued to observe till 1525. We have no more vivid source of the contemporary history, particularly as it concerned the maritime enterprise of the peninsular peoples. He wrote fluently, and, as he tells us, sometimes while waiting for dinner, and necessarily with haste. He jotted down first and unconfirmed reports, and let them stand. He got news by hearsay, and confounded events. He had candor and sincerity enough, however, not to prize his own works above their true value. He knew Columbus, and, his letters readily reflect what interest there was in the exploits of Columbus, immediately on his return from his first voyage; but the earlier preparations of the navigator for that voyage, with the problematical characteristics of the undertaking, do not seem to have made any impression upon Peter Martyr, and it is not till May of 1493, when the discovery had been made, and later in September, that he chronicles the divulged existence of the newly discovered islands. The three letters in which this wonderful intelligence was first communicated are printed by Harrisse in English, in his Notes on Columbus. Las Casas tells us how Peter Martyr got his accounts of the first discoveries directly from the lips of Columbus himself and from those who accompanied him; but he does not fail to tell us also of the dangers of too implicitly trusting to all that Peter says. From May 14, 1493, to June 5, 1497, in twelve separate letters, we read what this observer has to say of the great navigator who had suddenly and temporarily stepped into the glare of notice. These and other letters of[Pg 35] Peter Martyr have not escaped some serious criticism. There are contradictions and anachronisms in them that have forcibly helped Ranke, Hallam, Gerigk, and others to count the text which we have as more or less changed from what must have been the text, if honestly written by Martyr. They have imagined that some editor, willful or careless, has thrown this luckless accompaniment upon them. The letters, however, claimed the confidence of Prescott, and have, as regards the parts touching the new discoveries, seldom failed to impress with their importance those who have used them. It is the opinion of the last examiner of them, J. H. Mariéjol, in his Peter Martyr d'Anghera (Paris, 1887), that to read them attentively is the best refutation of the skeptics. Martyr ceased to refer to the affairs of the New World after 1499, and those of his earlier letters which illustrate the early voyage have appeared in a French version, made by Gaffarel and Louvot (Paris, 1885).

The representations of Columbus easily convinced Martyr that there opened a subject worthy of his pen, and he set about composing a special treatise on the discoveries in the New World, and, under the title of De Orbe Novo, it occupied his attention from October, 1494, to the day of his death. For the earlier years he had, if we may believe him, not a little help from Columbus himself; and it would seem from his one hundred and thirty-five epistles that he was not altogether prepared to go with Columbus, in accounting the new islands as lying off the coast of Asia. He is particularly valuable to us in treating of Columbus's conflicts with the natives of Española, and Las Casas found him as helpful as we do.

These Decades, as the treatise is usually called, formed enlarged bulletins, which, in several copies, were transmitted by him to some of his noble friends in Italy, to keep them conversant with the passing events.

A certain Angelo Trivigiano, into whose hands a copy of some of the early sections fell, translated them into easy, not to say vulgar, Italian, and sent them to Venice, in four different copies, a few months after they were written; and in this way the first seven books of the first decade fell into the hands of a Venetian printer, who, in April, 1504, brought out a little book of sixteen leaves in the dialect of that region,[Pg 36] known in bibliography as the Libretto de Tutta la Navigation de Re de Spagna de le Isole et Terreni novamente trovati. This publication is known to us in a single copy lacking a title, in the Biblioteca Marciana. Here we have the first account of the new discoveries, written upon report, and supplementing the narrative of Columbus himself. We also find in this little narrative some personal details about Columbus, not contained in the same portions when embodied in the larger De Orbe Novo of Martyr, and it may be a question if somebody who acted as editor to the Venetian version may not have added them to the translation. The story of the new discoveries attracted enough notice to make Zorzi or Montalboddo—if one or the other were its editor—include this Venetian version of Martyr bodily in the collection of voyages which, as Paesi novamente retrovati, was published at Vicentia somewhere about November, 1507. It is, perhaps, a measure of the interest felt in the undertakings of Columbus, not easily understood at this day, that it took fourteen years for a scant recital of such events to work themselves into the context of so composite a record of discovery as the Paesi proved to be; and still more remarkable it may be accounted that the story could be told with but few actual references to the hero of the transactions, "Columbus, the Genoese." It is not only the compiler who is so reticent, but it is the author whence he borrowed what he had to say, Martyr himself, the observer and acquaintance of Columbus, who buries the discoverer under the event. With such an augury, it is not so strange that at about the same time in the little town of St. Dié, in the Vosges, a sequestered teacher could suggest a name derived from that of a follower of Columbus, Americus Vespucius, for that part of the new lands then brought into prominence. If the documentary proofs of Columbus's priority had given to the Admiral's name the same prominence which the event received, the result might not, in the end, have been so discouraging to justice.