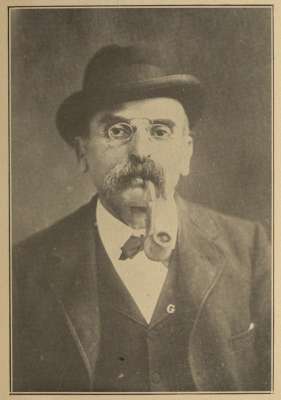

Yours truly, I. HERMANN

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/memoirsofveteran00hermiala |

Written by

CAPT. I. HERMANN

Who Served in the Three Branches of the Confederate Army

ATLANTA. GA.:

BYRD PRINTING COMPANY

1911

Copyright 1911

By I. Hermann

All rights reserved

The following reminiscences after due and careful consideration, are dedicated to the young, who are pausing at the portals of manhood, as well as womanhood, and who are confronted with illusory visions and representations, the goal of which is but seldom attained, even by the fewest fortunates, and then only by unforeseen circumstances and haphazards, not illustrated in the mapped out program for future welfare, greatness and success.

Often the most sanguine persons have such optimistic illusions, which, unless most carefully considered will lead them into irreparable errors. Even the political changes, often times necessary in the government of men, are great factors to smash into fragments the best and most illusory plans, and cast into the shadow, for a time being at least, the kindliest, philanthropic and best intentions of individual efforts, until the Wheel of Fortune again turns in his direction, casting a few sparks of hope in his ultimate favor, and which is seldom realized.

If the reader of the above has been induced to think and carefully consider, before acting hastily, the writer feels that he has accomplished some good in the current affairs of human events.

Entering the post-office for my daily mail, I noticed in the lobby, hanging on the wall, a beautiful, attractive and highly colored landscape and manhood therein displayed in its perfection, gaudily dressed in spotless uniforms; some on horseback, some afoot, with a carriage as erect and healthful demeanor that the artist could undoubtedly produce; he was at his best, setting forth a life of ease and comfort that would appeal to the youngster, patriot and careless individual, that therein is a life worth living for. Even the social features have not been omitted where men and officers stand in good comradeship. Peace and repose, and a full dinner pail are the environment of the whole representation.

It is the advertisement of an army recruiting officer, who wants to enlist young, healthy men for the service of the executive branch of our National Government, to defend the boundaries of our territory, to protect our people against the invasion of a foreign foe, to even invade[8] a foreign land, to kill and be killed at the behest of the powers that be, for an insult whether imaginary or real, that probably could have been settled through better entente, or if the political atmosphere would have thought to leave the matter of misunderstanding or misconstruction to a tribunal of arbitration.

The writer himself was once a soldier; the uniform he wore did not correspond with that of the picture above, it was rather the reverse in all its features. He enlisted in the Confederate service in 1861, when our homes were invaded, in defense of our firesides, and the Confederate States of America, who at that time, were an organized Government.

Usually an artist, when he represents a subject on canvas, uses a dark background, to bring forth in bright relief, the subject of his work. But I, not being an artist, reverse the matter in controversy, and put the bright side first.

When in 1861 the Southern States, known as the Slave States, severed their connection with the Federal Government and formed a Confederacy of their own, which under the Federal[9] Constitution and Common Compact, they had a perfect right to do, they sent Commissioners, composed of John Forsyth, Martin J. Crawford and A. B. Boman to Washington, with power to adjust in a peaceable manner, any differences existing between the Confederate Government and their late associates. Our Government refrained from committing any overt act, or assault, and proposed strictly to act on the defensive, until that Government, in a most treacherous manner, attempted to maintain by force of arms, property, then in their possession and belonging to the Confederate Government, and which they had promised to surrender or abandon. But on the contrary, they sent a fleet loaded with provisions, men and munitions of war, to hold and keep Fort Sumter, in the harbor of South Carolina, contrary to our expectations, and as a menace to our new born Nation.

Then, as now, there were State troops, or military organizations, and being on the alert, under the direction of our Government, and under the immediate command of General Beauregard, they fired on the assaulting fleet to prevent a most flagrant outrage, and after a[10] fierce conflict, the Fort was surrendered, by one Capt. Anderson, then in command.

Abraham Lincoln, the then President of the United States, called out 75,000 troops, which was construed by us as coercion on the part of the Federal Government, so as to prevent the Confederates from carrying out peaceably the maintenance of a Government already formed. To meet such contingency President Jefferson Davis called for volunteers. More men presented themselves properly organized into Companies, than we had arms to furnish. Patriotism ran high, and people took up arms as by one common impulse, and formed themselves into regiments and brigades.

The Federal Government, with few exceptions, had all the arsenals in their possession. We were therefore not in a condition to physically withstand a very severe onslaught, but when the Northern Army attempted on July 21, 1861, to have a holiday in Richmond, the Capital of the Confederate States, we taught them a lesson at Manassas, and inscribed a page in history for future generations to contemplate.

The Federal army under General Scott consisted of over 60,000 men, while that of General J. E. Johnston was only half that number. Someone asked General Scott, why he, the hero of Mexico, had failed to enter Richmond. He answered, because the boys that led him into Mexico are the very ones that kept him out of Richmond.

The proclamation of Abraham Lincoln calling out for troops was responded to with alacrity. In the meantime, we on the Confederate side, were not asleep; Washington County had then only one military organization of infantry called the Washington Rifles, commanded by Captain Seaborn Jones, a very gallant old gentleman, who was brave and patriotic. The following was a list of the Company's membership, who, by a unanimous vote, offered their services to the newly formed Government to repel the invader: (See Appendix A.). Their services were accepted, and they were ordered to Macon, Ga., as a camp of instructions, and for the formation of a regiment, of which the following[12] companies formed the contingent—their names, letters, and captains. (See Appendix B.)

J. N. Ramsey, of Columbus, Ga., was elected Colonel. We were ordered to Pensacola, Fla., for duty, and to guard that port, and to keep from landing any troops by our enemy who were in possession of the fort, guarding the entrance of that harbor. This was in the month of April, 1861. From Pensacola the regiment was ordered to Northwestern Virginia. The Confederate Capital was also changed from Montgomery, Ala., where the Confederate Government was organized, and Jefferson Davis nominated its President, to Richmond, Va.

About the middle of May, the same year, twenty-one young men of this County, of which the writer formed a contingent part, resolved to join the Washington Rifles, who had just preceded us on their way to Virginia. We rendezvoused at Davisboro, a station on the Central of Georgia Railway. We were all in high spirit on the day of our departure. The people of the neighborhood assembled to wish us Godspeed and a safe return. It was a lovely day and patriotism ran high. We promised a satisfactory result as soldiers of the Confederate States of America.

At Richmond, Va., we were met by President Davis, who came to shake hands with the "boys in gray", and speak words of encouragement. From Richmond we traveled by rail to Staunton, where we were furnished with accoutrements by Colonel Mikel Harmon, and which consisted of muskets converted into percussion cap weapons, from old revolutionary flint and steel guns, possessing a kicking power that would put "Old Maude" to shame. My little squad had resolved to stick to one another through all emergencies, to aid and assist each other and to protect one another. Those resolutions were carried out to the letter as long as we continued together. We still went by rail to Buffalo Gap, when we had to foot it over the mountains to McDowell, a little village in the Valley of the Blue Ridge. Foot-sore and weary we struck camp. The inhabitants were hospitable and kind, and we informed ourselves about everything in that country, Laurel Hill being our destination.

An old fellow whose name is Sanders, a very talkative gentlemen, told us how, he by himself ran a dozen Yankees; every one of us became interested as to how he did it, so he stated that one morning he went to salt his sheep in the[14] pasture—all of a sudden there appeared a dozen or more Yankee soldiers, so he picked up his gun, and ran first, and they ran after him, but did not catch him. We all felt pretty well sold out and had a big laugh, for the gentleman demonstrated his tale in a very dramatic way.

The following morning, we concluded to hire teams to continue our journey, which was within two days march of our destination. We passed Monterey, another village at the foot of the Alleghany Mountains, about twelve miles from McDowell. We crossed the Alleghany into Green Brier County, passed Huttensville, another little village at the foot of Cheat Mountain, from there to Beverly, a village about twelve miles from Laurel Hill, where we were entertained with a spread, the people having heard of our approach. We camped there that night, and passed commandery resolution upon its citizens, and their kind hospitality. The following day we arrived at Laurel Hill, where the army, about 3,000 strong, was encamped. The boys were glad to see us, and asked thousands of questions about their home-folks, all of which was answered as far as possible. The writer being a Frenchman, a rather scarce article in those days in this country, elicited no little[15] curiosity among the members of the First Georgia Regiment. Sitting in my tent, reading and writing, at the same time enjoying my pipe, I noted at close intervals shadows excluding the light of day—looking for the cause, the party or parties instantly withdrew. Major U. M. Irwin entered; I asked him the cause for such curiosity, he stated laughing, "Well, I told some fellows we'd brought a live Frenchman with us. I suppose those fellows want to get a peep at you." I at once got up, mounted an old stump, and introduced myself to the crowd: "Gentlemen, it seems that I am eliciting a great deal of curiosity; now all of you will know me as Isaac Hermann, a native Frenchman, who came to assist you to fight the Yankees." Having thus made myself known, I took the privilege to ask those with whom I came in contact their names, and what Company they belonged to, and thus in a short time I knew every man in the Regiment. We were now installed and regularly enrolled for duty.

Laurel Hill is a plateau situated to the right of Rich Mountain, the pass of which was occupied by Governor Wise, with a small force.

In the early part of July, General McClelland, in command of the Federal troops, made a demonstration on our front. Our position was somewhat fortified by breastworks; the enemy came in close proximity to our camp and kept us on the Qui-vive; their guns were of long range, while ours would not carry over fifty yards. Picket duties were performed by whole companies, taking possession of the surrounding commanding hills. Many shots hissed in close proximity, without our being able to locate the direction from which they came, and without our even being able to hear the report of the guns. Very little damage, however, was done, except by some stray ball, now and then. It was the writer's time to stand guard, not far in front of the camp, his beat was alongside the ditches. In front of me the enemy had planted a cannon. The shots came at regular intervals in direct line with my beat, but the shots fell somewhat short, by about fifty to seventy-five yards. I saw many hit the ground.[17] When Lieutenant Colonel Clark, came round on a tour of inspection, I remarked, "Colonel, am I placed here as a target to be shot at by those fellows yonder. One of their shots came rather close for comfort." He said, "Take your beat in the ditch, and when you see the smoke, tuck your head below the breastworks"—which was three and one-half feet deep the dirt drawn towards the front, which protected me up to my shoulders. For nearly two hours, until relieved, I kept close watch for the smoke of their gun, which I approximated was about a mile distant, and there I learned that it took the report of the cannon eight seconds to reach me after seeing the smoke, and the whiz of the missile four seconds later still; this gave me about twelve seconds to dodge the ball—anyhow, I was very willing when relief came, for the other fellow to take my place. In the afternoon, minnie balls rather multipherous, were hissing among the boys in camp, but up to that time there was no damage done, when a cavalryman came in and reported that some of the enemy was occupying an old log house situated about a half mile in front of us, and it was there through the cracks of that building came the missiles that made the fellows dodge about. General Garnett, our Commander, ordered out[18] two companies of infantry, who, taking a long detour through the woods placed themselves in position to receive them as they emerged from the building, and with two pieces of artillery, sent balls and shells through their improvised fort. Out came the "Yanks" only to fall into the hands of those ready to give them a warm reception.

On that evening, three days rations were issued. At dark it commenced drizzling rain; we were ordered to strike camp, and we took up the line of march to the rear, when I learned that the enemy had whipped out Governor Wise's forces on Rich Mountain and threatened our rear. We marched the whole of that night, only to find our retreat to Beverly blockaded by the enemy who had felled many trees across the road, the only turn pike leading to that place.

We had to retrace our steps for several miles, and take what is known as mountain trail, leading in a different direction, marching all day. The night again, which was dark and dreary multiplied our misgivings. The path we followed, was as stated, a narrow mountain path, on the left insurmountable mountains, while on the right very deep precipices; many teams that[19] left the rut on account of the darkness, were precipitated down the precipices and abandoned. Thus, after two nights and one day of steady marching, we arrived at Carricks' Ford, a fordable place on the north fork of the Potomac River. The water was breast-deep, and we went into it like ducks, when of a sudden, the Yankees appeared, firing into our column. They struck us about and along the wagon train, capturing the same, while the advance column stampeded. We lost our regimental colors, which were in the baggage wagon, in charge of G. W. Kelly, who abandoned it with all the Company's effects, to save himself.

Colonel Ramsey, in fact all our officers were elected on account of their cleverness at home. This being a strictly agricultural country, the men and officers knew more about farming than about military tactics. Colonel Ramsey was an eminent lawyer of Columbus, Georgia. He gave the command, "Georgian, retreat," and the rout was complete. It was a great mistake that the Government did not assign military men to take charge in active campaigns; many blunders might have been evaded and many lives spared at the beginning of the war.

One half of my regiment was assigned as rear[20] guards and marched therefore, in the rear of the column behind the wagon train. We were consequently left to take care of ourselves the best we could. General Garnett was killed in the melee. Had we had officers who understood anything about military tactics, these reminiscences might be told differently.

As soon as we heard firing in our front, we at once formed ourselves into line of battle, in a small corn patch across the stream, on our immediate right, at the foot of a high mountain. It seemed to have been new ground and the corn was luxuriantly thick. The logs that were there were rolled into line, thus serving as terraces, and also afforded us splendid breastworks. We were hardly in position, when artillery troops appeared and crossed the ford, not seventy-five yards from where we were in line, seeing them, without being seen ourselves. Major Harvey Thompson, who was in Command of our forces, which were not over four hundred and fifty strong, seeing some men making ready to fire, gave orders not to fire, as they were our own men crossing the stream, and thus lost the opportunity of making himself famous, for it proved to be the enemy's artillery in our immediate front. Had he given orders to fire[21] and charge, we could have been on them before they could possibly have formed themselves into battery, captured their guns, killed and captured many of their men, and would have turned into victory what proved to have become a disastrous defeat.

Thus being cut off from our main forces, who were in full retreat, and fearing to be captured, we climbed the mountain in our rear, expecting to cut across in a certain direction, and rejoin our forces some distance beyond. Thus began a dreary march of three days and four nights in a perfect wilderness, soaked to the bone and nothing to eat, cutting our way through the heavy growth of laurel bushes, we had to take it in Indian file, in single column.

Many pathetic instances came to my observation; some reading testaments, others taking from their breast-pocket, next to their heart, pictures of loved ones, dropping tears of despair, as they mournfully returned them to their receptacle. An instance which impressed itself forcibly on my mind, was the filial affection displayed between father and son, and in which the writer put to good use, the Biblical story of King Solomon, where two women claimed the same child, but in this instance[22] neither wanted to claim. It was thus: Captain Jones found a piece of tallow candle about one inch long in his haversack, and presented it to his son, Weaver, saying, "Eat that, son, it will sustain life;" "No, father, you eat it, I am younger than you, and stronger, and therefore can hold out longer." There they stood looking affectionately at each other, the Captain holding the piece of candle between his fingers. So I said, "Captain, hand it to me, I will divide it for you." Having my knife in hand, I cut it lengthwise, following the wick, giving each half, and passing the blade between my lips. It was the first taste of anything the writer had had in four days.

When night overtook us, we had to remain in our track until daylight would enable us to proceed. When at about nine o'clock A. M. word was passed up the line, from mouth to mouth—"A Guide! A man and his son who will guide us out of here." Then Major Thompson, who was in front sent word down the line for the men to come up. The guides sent word up the line to meet them half way, that they were very tired, so it was arranged that Major Thompson met them about center, where the writer was. The guides introduced themselves as Messrs. Parson, father and son. The senior was a man of about fifty years, rather ungainly as to looks, and somewhat cross-eyed, while his son was a strong athletic young man, about twenty-three. They said they were trappers, collecting furs for the market. It must be remarked that that country was perfectly wild, and uninhabited, for during all this long march I had not seen a single settlement, but it contained many wild beasts, such as bears, panthers, foxes, deer, etc. He related that a tall young man by the name of Jasper Stubbs, belonging to Company E, First Regiment, Washington Rifles, came to his[24] quarters very early this morning, inquiring if any soldiers had passed by, saying he found a nook under a projecting rock where he stood in column the night before, and to protect himself from dew, he lay down to rest, and fell asleep. When he awoke, it was day and he found his comrades gone, and that he was by himself. The surface of ground or rock, was a solid moss-bed, consequently he could not tell which way our tracks pointed, and he happened to take the reverse course which we went, and thus came to where the Parsons lived. Stubbs was missing, thus proving that the men's story must be true. It must also be remembered that the majority of the people in Western Virginia were in sympathy with the enemy, and thus possessed of many informers or spies, who would give information as to our whereabouts and doings.

A conference was held among the officers as to what was best to be done. Parson claimed to be in sympathy with the South, and he knew that we would not be able to carry out our design, and that we would all perish, so he put out to lead us out of our dilemma. Major Thompson was for putting the Parsons under arrest, and force them to lead us in the direction[25] we first assumed, or perish with us. Parsons spoke up and said, "Gentlemen, I am in your power; the country through which you propose to travel is not habitable, I have been raised in these regions, and there is not a living soul within forty miles in the direction you propose to go, and at the rate you are compelled to advance, you would all perish to death, and your carcasses left for food to the wild beasts of the forest." The conference was divided, some hesitated, others were for adopting Major Thompson's plan, when the writer stepped forward, saying, "Gentlemen, up to now, I have obeyed orders, but I for one, prefer to be shot by an enemy's bullet, than to perish like a coward in this wild region." Captain Jones tapped me on the shoulder, remarking; "Well spoken, Hermann, those are my sentiments—Company E, About Face!". Captain Crump, commanding Company I, from Augusta, Ga., followed suit, and thus the whole column faced about, ready to follow the Parsons.

The writer made the following proposition: That Mr. Parson and son be disarmed, for both carried hunting rifles; that I would follow them within twenty paces, while the column should follow within two hundred yards, thus in case of[26] treachery they would be warned by report of my gun, that there is danger ahead. These precautions I deemed necessary in case of an ambush. Addressing myself to our guides, I said, "Gentlemen, you occupy an enviable position; if you prove true, of which I have no doubt myself, you'd be amply rewarded, but should you prove otherwise, your hide is mine, and there is not enough guns in Yankeedom to prevent me from shooting you." At this point, a private from the Gate City Guards, whose name is Wm. Leatherwood, remarked, "You shall not go alone, I will accompany you." I thanked him kindly, saying I would be glad if he would. Thus we retraced our steps, following our leaders, when after about three miles march we struck a mountain stream, in the bed of which we waded for nine miles, the water varying from knee to waist deep, running very rapidly over mossy, slippery rocks, and through gorges as if the mountains were cut in twain and hewn down. In some places, the walls were so high, affording a narrow dark passage, I don't believe God's sun ever shone down there. I was so chilled, I felt myself freezing to death in mid summer, for it was about the 17th of July; darkness was setting in, and I had not seen the sun that day, although the sky was cloudless, when[27] to my great relief we came to a little opening on our left, the mountain receding, leaving about an acre of level ground, with a luxuriant growth of grass. Our guides said they lived within a quarter of a mile from there. I said, let us rest and wait for the rest of the men. When after a little rest, I started again, I was too weak to make the advance, although provisions were in sight. I had to be relieved, and some others took my place, while I lay exhausted on the grass. Happily some of the men had paper that escaped humidity; loading a musket with wadding, they fired into a rotten stump, setting it on fire, and by persistent blowing, produced a bright little flame, which soon developed into a large camp fire, around which the boys dried themselves.

Parson proved himself a noble, patriotic host. After a couple of hours, he sent us a large pone of corn-bread, baked in an old-fashioned oven. I received about an inch square as my share,—the sweetest morsel that ever passed my lips. It was sufficient to allay the gnawing of my empty stomach,—it had a strange effect on me, for every time I would stand up, my knees would give way and down I went otherwise I felt no inconvenience.

It was a remarkable fact that every man was able to keep up with our small column and we did not lose a single man up to that time.

The next morning Mr. Parson drove up two nice, seal fat beeves,—to get rations was a quick performance, and the meat was devoured before it had time to get any of the animal heat out of it, some ate it raw, others stuck it on the ramrod of their gun and held it over the fire, in the meantime biting off great mouthfulls while the balance was broiling on his improvised cooking utensil. Mr. Parson also brought us some meal, which being made into dough was baked in the ashes, and thus we all had a square meal and some left to carry in our haversack.

Mr. Parson was tolerably well to do, he owned some land, raised his truck, had a small apple orchard, and indulged in stock-raising. He owned several horses and some of the officers bought of him. The writer feeling badly jaded, also concluded he would buy himself a horse, and paid his price, $95.00 for a horse, but Major Thompson, being of a timid nature, was afraid that too many horsemen might attract attention, refused to let me ride by the wagon-road, so Mr. Parson said there was a mountain path that I could follow that would[30] lead in the big road some few miles beyond, but that I would have to lead the animal for about a couple of miles, when I would be able to ride. Dr. Whitaker, a worthy member of my Company, and a good companion, offered me his services to get the animal over the roughest part of the route. I accepted his offer, and promised that we would ride by turns, so I took the horse by the bridle and led him, Whitaker following behind, coaxing him along. The mountain was so steep I had to talk to keep the horse on his feet, but nevertheless he slipped several times and we worried to get him up again. We made slow headway; the column had advanced, and we lost sight of it, and were left alone, worrying with the horse, who finally lost foothold again, and rolled over. The writer was forced to turn loose the bridle to keep from being dragged along into the hollow. The horse rolled over and over, making every effort to gain his feet, but to no avail, until he reached the bottom, where he appeared no bigger than a goat. I felt sorry for the poor animal, so I went down, took off his saddle and bridle, placed them on a rock, and left him to take care of himself. I rejoined Dr. Whitaker. Relieved of our burden, we followed the trail made by the column. About sunset we caught sight of them, just as[31] they crossed Green Brier River, a wide, but shallow stream. At that place the water was waist deep in the center, running very swift, as mountain streams do, over slippery moss-covered rocks. When center of the river, I lost foot hold and the stream, swift as it was, swept me under, and in my feeble condition I had a struggle to recover myself. I lost my rations, which were swept down stream, a great loss to me, but undoubtedly served as a fine repast for the fishes which abounded in those waters.

The column continued its line of march, passing a settlement, the first dwelling I had seen in five days. I called at the gate; receiving no answer, I walked into the porch; the door being ajar, I pushed it open and found an empty room, with the exception of a wooden bench, and an old-fashioned, home-made primitive empty bedstead, with cords serving to support the bedding that the owners had hurriedly removed before our arrival. I called again. Presently a young woman presented herself. After passing greetings of the day I asked, "Where are the folks?" She said, "They are not here," (the surroundings indicated a hasty exit). I said, "So I see. Where are they?" She said she did not know, undoubtedly not willing to divulge. "Who lives[32] here?" "Mr. Snider." "And you don't know where he is?" "No, he heard you all were coming, and not being in sympathy with you all, he left." "Well, he ought not to have done so, nobody would have harmed him or hurt a hair on his head. He is entitled to his opinion, as long as he does not take up arms against us." So I recounted the accident that had befallen me, and wanted to replenish my provisions. I asked if I could buy something to eat. She said, "There are no provisions in the house", "Well, I hope you would not object to my making a fire in this fire-place to dry myself." She said she had no objection. It must be remembered that the fire-places in those days were very roomy indeed. I found wood on the woodpile, and soon had a roaring fire. It was late in the evening, and I intended to pass that night under shelter, for I was chilled to the bone. In moving the bench in front of the fire, on which to spread my jacket to dry, I noticed a pail covered, and full of fresh milk, "Well, you can sell me some of that milk, can't you?" She said, "You can have all you want for nothing." I thanked her and said I wish I had some meal and I could well make out. She said, "I will see if I can find any", and presently she returned with sufficient to make myself a large[33] hoe-cake. I baked the same on an old shovel. While it was baking my clothes were drying on my body, affording a luxuriant steam bath. I had a tin cup. I drank some of the milk and had a plentiful repast. I handed her a quarter of a dollar to pay for the meal, which she accepted with some hesitancy. All at once the girl disappeared and left me in charge. It was most dark, when someone hollowed at the gate; recognizing the voices, I found them to be two men of my Company, viz., G. A. Tarbutton and J. A. Roberson. I met them and invited them in. To tell the truth, I did not much like the mysterious surroundings of those premises, especially as the girl asked me not to divulge that she let me have some meal.

My comrades and self took in the situation; we conferred with one another and agreed to spend the night under shelter in a warm room, a luxury not enjoyed in some time and not to be abandoned. They had informed me that the Column had encamped less than a quarter of a mile beyond and they had returned to this place in search of some Apple Jack. We concluded to take it by turns, while two of us are asleep, the third will stand guard and keep up the fire, for the reader must know that notwithstanding[34] the season, the nights were very cold in those mountain regions and were especially so with wet garments on.

The following morning my comrades left, but before leaving we disposed of the milk in the pail. I remained in the hope of again seeing my charming hostess, and induce her to sell me some provisions for my journey along. I saw in the woods, some old hens scratching, and I thought I might persuade her to sell me one. Presently she came with a plate of ham, chicken and biscuits which she offered me. I accepted, and not wishing to embarrass her, did not ask any questions. Presently, old man Snider appeared. He was a fine looking specimen of manhood, had a ruddy complexion and appeared physically Herculean. After exchanging a little commonplace talk, he followed me to where the boys camped. He was seemingly astonished to see so many gentlemen among the so-called savage rebels. I asked him if he could induce his daughter to bake me a chicken, he answered, "I suppose I could." "What will it be worth?" "Half a dollar" he guessed. I gave him the money and he said he would bring me the chicken, which he did, and it was a fine one, well cooked.

The people in that thinly populated section of the country lived a very primitive life, they were mostly ignorant. They did their own work, had plenty to live on, owned no negroes and were very kind-hearted after you got acquainted. They had strange notions about the Rebels, thinking we were terrible fellows. The original settlers of Northwestern Virginia were Dutch, a very simple and hard-working honest people.

At about three o'clock in the afternoon, having had a long rest, we again took up the line of march by short stages, still under the guidance of one of our guides, and from that day on, we continued our march, passing Cheat Mountain, Allegheny Mountains, until finally we reached McDowell. Coming down Cheat Mountain, the boys were treated to a strange sight, especially those who were raised in a low country and who had never seen any mountains, for in those days there was not much traveling done, and the majority of the people did not often venture away from their homes.

The little village of Huttensville lies just at the foot of Cheat Mountain, a mountain of great altitude. The houses below us did not appear to be larger than bird cages, but plainly in[36] view, first to the right and then to the left, as the pike would tack, the mountain being very steep. It was a lovely day, the sun had risen in all its splendor, when as if by magic, our view below us was obscured by what seemed to be a very heavy fog, and we lost sight of the little village. Still the sun was shining warm, and as we were going down hill it was easy going, and as we approached the village, the veil that had obscured our view lifted itself and the people reported to have experienced one of the heaviest storms in their lives, the proof of which we noticed in the mud and washouts which were visible, while we who were above the clouds did not receive a single drop.

At McDowell we formed a reunion with the rest of our forces, who in their flight made a long detour, passing through a portion of Maryland adjoining that part of West Virginia. The following evening we had dress parade and the Adjutant's report of those who were missing. The writer does not remember the entire casualties of that affair, but found that his little squad of twenty-one were all present or accounted for.

My friend, Eagle, from whom we hired teams to carry us to Laurel Hill was present and he came to shake hands with me while we were in line; he was glad to see me. A general order to disband the regiment for ten days was read, in order to enable the men to seek the needed rest. Mr. Eagle came to me at once, saying, "I take care of you and your friends, the twenty-one that I hauled to Laurel Hill, at my house. It shall not cost you a cent", a most generous and acceptable offer. I called for my Davisboro fellows, and followed Mr. Eagle to his home, where he entertained us in a most substantial manner. He was a man well-to-do, an old bachelor.[38] The household consisted of himself and two spinster sisters, all between forty and fifty years of age; and a worthy mother in the seventies, also a brother who was a harmless lune, roving at will and coming home when he pleased, a very inoffensive creature; his name was Chris. The mother, although for years in that country, still could not talk the English language. Untiringly and seemingly in the best of mood, they performed their duties in preparing meals for that hungry army. Chris got kinder mystified to see so many strangers in the house. He walked about the premises all day, saying, "Whoo-p-e-ee Soldiers fighting against the war", and no matter what you asked him, his reply was, "Whoo-o-p-e-ee, Soldiers fighting against the war-ha-ha-ha-ha!"

At the expiration of the ten days leave, we bade our host good-bye. We wanted to remunerate him, at least in part, for all of his trouble in our behalf, but he would not receive the least remuneration, saying, "I am sorry I could not have done more." We rendezvoused in the town, but a great many were missing on account of sickness, the measles of a very virulent nature having broken out among the men, and many succumbed from the disease. We were ordered[39] back to Monterey and went into camp. The measles still continued to be prevalent and two of my Davisboro comrades died of it, viz., John Lewis and Noah Turner, two as clever boys as ever were born. I felt very sad over the occurrence. Their bodies were sent home and they were buried at New Hope Church.

General R. E. Lee, rode up one day, and we were ordered in line for inspection, he was riding a dapple gray horse. He looked every inch a soldier. His countenance had a very paternal and kind expression. He was clean shaven, with the exception of a heavy iron gray mustache. He complimented us for our soldiery bearing. He told Captain Jones that he never saw a finer set of men. We camped at Monterey for a month. During all this time, when the people at home became aware of our disaster, they at once went to work to make up uniforms and other kinds of wearing apparels. Every woman that could ply a needle exerted herself, and before we left Monterey for Green Brier, Major Newman, who always a useful and patriotic citizen, made his appearance among the boys, with the product of the patriotic women of Washington County. Every man was remembered munificently, and it is due to the[40] good women of the county that we were all comfortably shod and clothed to meet the rigorous climate of a winter season in that wild region.

While still in camps at Monterey, the Fourteenth Georgia Regiment, on their way to Huntersville, with a Company of our County, under command of Captain Bob Harmon, encamped close to us. The boys were glad to meet and intermingled like brothers. A day or so after we were ordered to move to Green Brier at the foot of the Allegheny and Cheat Mountains, the enemy occupying the latter, under general Reynolds.

Our picket lines extended some three miles beyond our encampment, while the enemy's also extended to several miles beyond their encampment, leaving a neutral space unoccupied by either forces. Often reconnoitering parties would meet beyond the pickets and exchange shots, and often pickets were killed at their posts by an enemy slipping up through the bushes unaware to the victim. I always considered such as willful murder.

It became my time to go on picket; the post assigned to me was on the banks of the River, three miles beyond our camps. The night before one of our men was shot from across the River.[42] Usually three men were detailed to perform that duty, so that they can divide watch every two hours, one to guard and two to sleep, if such was possible. On that occasion the guard was doubled and six men were detailed, and while four lay on the ground in blankets, two were on the lookout. The post we picked out was under a very large oak; in our immediate rear was a corn field the corn of which was already appropriated by the cavalry. The field was surrounded by a low fence and the boys at rest lay in the fence corners. It was a bright starlight September night, no moon visible, but one could distinguish an object some distance beyond. I was on the watch. It was about eleven P. M., when through the still night, I heard foot-steps and the breaking of corn stalks. I listened intently, and the noise ceased. Presently I heard it again; being on the alert, and so was my fellow-watchman, we cautiously awoke the men who were happy in the arms of Morpheus, not even dreaming of any danger besetting their surroundings. I whispered to them to get ready quietly, that we heard the approach of someone walking in our front. The guns which were in reach beside them were firmly grasped. We listened and watched, in a stooping position, when the noise started again, yet a little [43]more pronounced and closer. We were ready to do our duty. I became impatient at the delay, and not wishing to be taken by surprise, I thought I would surprise somebody myself, so took my musket at a trail, crept along the fence to reconnoiter, while my comrades kept their position. When suddenly appeared ahead of me a white object, apparently a shirt bosom. I cocked my gun, but my target disappeared, and I heard a horse snorting. On close inspection, I found that it was a loose horse grazing, and what I took for a shirt bosom was his pale face, which sometimes showed, when erect, then disappeared while grazing. I returned and reported, to the great relief of us all. Heretofore, men on guard at the outpost would fire their guns on hearing any unusual noise and thus alarming the army, which at once would put itself in readiness for defense, only to find out that it was a false alarm and that they were needlessly disturbed. Such occurrences happened too often, therefore a general order was read that any man that would fire his gun needlessly and without good cause, or could not give a good reason for doing so would be court-martialed and dealt with accordingly. Therefore, the writer was especially careful not to violate these orders.

At another time it became again my lot to go on vidette duty. This time it was three miles in the opposite direction in the rear of the camp in the Allegheny, in a Northwesterly direction, in a perfect wilderness, an undergrowth of a virgin forest. It was a very gloomy evening the clouds being low. A continual mist was falling. It was in the latter part of September. We were placed in a depressed piece of ground surrounded by mountains. The detail consisted of Walker Knight, Alfred Barnes and myself. Corporal Renfroe, whose duty was to place us in position, gave us the following instructions and returned to camp: "Divide your time as usual, no fire allowed, shoot anyone approaching without challenge." Night was falling fast, and in a short while there was Egyptian darkness. We could not even see our hands before our eyes. There was a small spruce pine, the stem about five inches in diameter, with its limbs just above our heads. We placed ourselves under it as a protection from the mist, and in case it would rain. All at once, we heard a terrible yell, just such as a wild cat might send forth, only many times louder. This was answered it seemed like, from every direction. Barnes remarked "What in the world is that?" I said, "Panthers, it looks like the woods are full of them." The[45] panthers, from what we learned from inhabitants are dangerous animals, and often attack man, being a feline species, they can see in the dark. I said, "There is no sleep for us, let us form a triangle, back to back against this tree, so in case of an attack, we are facing in every direction." Not being able to see, our guns and bayonets were useless, and we took our pocket knives in hand in case of an attack at close quarters. The noise of these beasts kept up a regular chorus all night long, and we would have preferred to meet a regiment of the enemy than to be placed in such a position. We were all young and inexperienced. I was the oldest, and not more than twenty-three years old. Walker Knight said, "Boys, I can't stand it any longer, I am going back to camp." I said, "Walker, would you leave your post to be court-martialed, and reported as a coward? Then, you would not find the way back, this dark night, and be torn up before you would get there. Here, we can protect each other." Occasionally we heard dry limbs on the ground, crack, as if someone walking on them. This was rather close quarters to be comfortable, especially when one could not see at all. There we stood, not a word was spoken above a whisper, when we heard a regular snarl close by, then Barnes[46] said, "What is that?" I said, "I expect it is a bear." All this conversation was in the lowest whisper; to tell the truth, it was the worst night I ever passed, and my friend Knight, even now says that he could feel his hair on his head stand straight up.

My dear reader, don't you believe we were glad when day broke on us? It was seemingly the longest night I ever spent, and so say my two comrades.

The country from Monterey to Cheat Mountain was not inhabited, with the exception of a tavern on top of the Allegheny, where travelers might find refreshments for man and beast. The enemy often harassed us with scouting parties, and attacking isolated posts. To check these maneuvres, we did the same; so one evening, Lieutenant Dawson of the Twelfth Georgia Regiment, Captain Willis Hawkins' Company from Sumter County, and which regiment formed a contingent part of our forces at Green Brier River, came to me saying, "Hermann, I want you tonight." He was a fearless scout, a kind of warfare that suited his taste, and he always called on me on such occasions. And after my last picket experience, I was only too willing to go with him, as it[47] relieved me from army duty the day following, and I preferred that kind of excitement to standing guard duty.

We left at dark, and marched about four miles, towards the enemy's camp to Cheat River, a rather narrow stream to be a river. A wooden bridge spanned the stream. We halted this side. On our right was a steep mountain, the turn pike or road rounded it nearly at its base. The mountain side was covered with flat loose rocks of all sizes, averaging all kinds of thickness. By standing some on their edge, and propping them with another rock, afforded fine protection against minnie balls. In this manner we placed ourselves in position behind this improvised breastworks.

The mot d'ordre was not to fire until the command was given. We were ten in number, and the understanding was to fire as we lay, so as to hit as many as possible. At about ten o'clock P. M. we heard the enemy crossing the bridge, their horses's hoofs were muffled so as to make a noiseless crossing, and take our pickets by surprise. They came within fifty yards of us and halted in Column. Lieutenant Dawson commanded the man next to him to pass it up the line to make ready to shoot, when he commanded[48] in a loud voice, "Fire!" Instantly, as per one crack of a musket, all of us fired, and consternation reigned among the enemy's ranks; those that could get away stampeded across the bridge. We did not leave our position until day. When we saw the way was clear, we gathered them up, took care of the wounded and buried the dead—several of our shots were effective. On the 3rd of October, they made an attack on us in full force, and while they drove in our pickets, we had ample time to prepare to give them a warm reception.

The following is a description of the battle ground and a description of our forces:

On the extreme right, in an open meadow, not far from the banks of the river, was the First Georgia Regiment, lying flat on the grass; to the immediate left and rear was a battery of four guns, on a mount immediately confronting the turn pike, and fortified by breastworks, and supported by the Forty-fourth Virginia Regiment, commanded by Colonel Scott; further to left, across the road was a masked battery, with abatis in front, Captain Anderson commanding, and supported by the Third Arkansas Regiment and the Twelfth Georgia Regiment, commanded by Colonels Rusk and[49] Johnston respectively. As the enemy came down the turn pike, the battery on our left, commanding that position, opened on them, the enemy from across the river responded with alacrity, and there was a regular artillery duel continuously. Their infantry filed to their left, extending their line beyond that of the First Georgia, they followed the edge of the stream at the foot of the mountain. We detached two Companies from the Regiment further to our right, to extend our line. They were not more than two hundred yards in front. The balance of the regiment lay low in its position; the order was to shoot low, and not before we could see the white of their eyes.

The enemy would fire on us continually, but the balls went over us and did no damage. While maneuvring thus on our right, they made a vigorous attack on Anderson's battery, but were repulsed with heavy loss. Late in the afternoon they withdrew. Our casualties were very small, and that of the enemy considerable.

Colonel Ramsey, who, early that morning went out on an inspection tour, dismounted for some cause, his horse came into camp without a rider, and we gave him up for lost, but later, a little before dark, he came in camp, to the great[50] rejoicing of the regiment, for we all loved him. General Henry R. Jackson was our commander at that time, and soon afterwards was transferred South.

The enemy had all the advantage by the superiority of their arms, while ours were muzzle loaders, carrying balls but a very short distance; theirs were long range, hence we could not reach them only at close quarters. A very amusing instant was had during their desultory firing. The air was full of a strange noise; it did not sound like the hiss of a minnie-ball, nor like that of a cannon ball. It was clearly audible all along the line of the First Georgia; the boys could not help tucking their heads. The next day some of the men picked up a ram rod at the base of a tree where it struck broadside, and curved into a half circle. It was unlike any we had, and undoubtedly the fellow forgot to draw it out of the gun, fired it at us, and this was the strange sound we heard which made us dodge. A few nights later, a very dark night, we sent out a strong detachment, under Command of Colonel Talliaferro to cut off their pickets, which extended to Slavins Cabin (an old abandoned log house). To cross the river we put wagons in the run; a twelve inch plank connected the wagons and served as a bridge.[51] On the other side of the river was a torch bearer, holding his torch so that the men could see how to cross. The torch blinded me, and instead of looking ahead, I looked down. It seemed that the men with the torch shifted the light, casting the shadow of a connecting plank to the right, when instead of stepping on the plank, I stepped on the shadow, and down in the water I went (rather a cold bath in October) and before morning, my clothing was actually frozen. In crossing Cheat River Bridge, the road tacked to the left, making a sudden turn, which ran parallel with the same road under it. The head of the column having reached there, the rear thinking them to be enemies, fired into them. Haply no one was hurt before the mistake was discovered, but the enemy got notice of our approach by the firing, and had withdrawn, so the expedition was for naught. We were back in camp about eight o'clock the following morning.

At the latter end of the month Colonel Edward Johnson concluded to attack General Reynolds in his stronghold on Cheat Mountain.

The Third Arkansas Regiment, under command of Colonel Rusk, was detached and sent to the rear, taking a long detour a couple of days ahead, and making demonstrations, while the[52] main force would attack them in front. Colonel Rusk was to give the signal for attack. Early in the night we sent out a large scouting party to attack their pickets, and drive them in. Lieutenant Dawson was in command. Early that day we started with all the forces up Cheat Mountain, a march of twelve miles. During the progress of our march the advance guard having performed what was assigned them to do, returned by a settlement road running parallel with the turn pike for some distance, when of a sudden, balls were hissing among us and some of the men were hit. The fire was returned at once, and flanker drawn out whose duty it was to march on the flank of the column, some twenty paces by its side, keeping a sharp lookout. I mistook the order, and went down into the woods as a scout, the firing still going on, and I was caught between them both. I hugged close to the ground keeping a sharp lookout to my right. When I recognized the Company's uniform, and some of my own men, I hollowed at them to stop firing, that they were shooting our own men, when they hollowed, "Hurrah for Jeff Davis," when from above, Colonel Johnson responded, "Damn lies, boys, pop it to them," when Weaver Jones stuck a white handkerchief on his bayonet and the firing ceased.[53] Sergeant P. R. Talliaferro was hit in the breast by a spent ball. Weaver had a lock of his hair just above his ear cut off as though it had been shaved off. One man was wounded and bled to death, another was wounded and recovered. Such mistakes happened often in our lines for the lack of sound military knowledge.

The man that bled to death was from the Dahlonega Guards. He said while dying, that he would not mind being killed by an enemy's bullet, but to be killed by his own friends is too bad. Everything was done that could be done for the poor fellow, but of no avail.

The column advanced to a plateau, overlooking the enemy's camp. We placed our guns in battery, waiting for the Rusk signal, which was never given; we waited until four o'clock P. M. and retraced our steps without firing a gun. We saw their lines of fortification and their flags flying from a bastion, but not a soul was visible. We thought Reynolds had given us the slip and that we would find him in our rear and in our camp before we could get back, so we double quicked at a fox trot, until we reached our quarters in the early part of the night.

Colonel Rusk came in two days afterward, and reported that his venture was impracticable.[54] Cold winter was approaching with rapid strides and rations were not to the entire satisfaction of our men. The beef that was issued to us, although very fine, had become a monotonous diet, and the men longed for something else, they had become satiated with it, so I proposed to Captain Jones that if he would report me accounted for in his report, that I would go over to Monterey and McDowell on a foraging expedition, and bring provisions for the Company. He said he would, but I must not get him into trouble, for the orders were that no permits be issued for anyone to leave camp and that all passes, if any be issued, must be countersigned by Captain Anderson, who was appointed Commander of the post. We still were without tents for they were captured by the enemy at Carricks Ford, and we sheltered ourselves the best we could with the blankets we had received from home. The snow had fallen during the night to the depth of eight inches, and it was a strange sight to see the whole camp snowed under, (literally speaking). When morning approached, the writer while not asleep, was not entirely aroused. He lay there under his blanket, a gentle perspiration was oozing from every pore of his skin, when suddenly, he aroused himself, and rose up.[55] Not a man was to be seen, the hillocks of snow, however, showed where they lay, so I hollowed, "look at the snow." Like jumping out of the graves, the men pounced up in a jiffy, they were wrestling and snowballing and rubbing each other with it. After having performed all the duties devolving upon me that afternoon, I started up the Allegheny where some members of my Company with others, were detailed, building winter quarters. Every carpenter in the whole command was detailed for that purpose.

When some three miles beyond camps, I noted a little smoke arising as I approached. I noted that it was the outpost. My cap was covered with an oil cloth, and I had an overcoat with a cape, such as officers wore; hence the guard could not tell whether I was a private, corporal or a general. I noticed that they had seen me approach. One of them advanced to the road to challenge me, but I spoke first. I knew it was against the orders to have a fire at the outpost on vidette duty so I said, "Who told you to have a fire? Put out that fire, sirs, don't you know it is strictly prohibited?"—"What is your name—what Company do you belong to, and what is your regiment?" all of which was answered. I took my little note book and pencil, and made an entry, or at least made a bluff in this direction, and said, "You'll hear from me again." I had the poor fellow scared pretty badly, and they never even made any demand on me to find out who I was. They belonged to Colonel Scott's regiments. The bluff worked like a charm, and I marched on. When about six miles from camp, I was pretty tired, walking in the snow and up-hill. I saw General[57] Henry R. Jackson, and Major B. L. Blum, coming along in a jersey wagon. The General asked me where I was going,—it was my time to get a little scared. I answered that I was going on top the Allegheny where they built winter quarters. "Get in the wagon, you can ride, we are going that way." I thanked them; undoubtedly the General thought that I was detailed to go there and to assist in that work. This is the last I saw of General Jackson in that country.

Among the men I found Tom Tyson, Richard Hines, William Roberson (surnamed "Crusoe"). I spent the night with them in a cabin they had built and the following morning I took an early start down the mountain toward Monterey. It had continued to snow all the night and it lay to the depth of twelve inches. I could only follow the road by the opening distance of the tree tops, and which sometimes was misleading. I passed the half-way house, known as the tavern, about 9 o'clock A. M. Four hundred yards beyond, going in an oblique direction at an angle of about 45 degrees, I saw a large bear going through the woods; he was a fine specimen, his fur was as black as coal. I approximate his size as about between three hundred and four hundred pounds. He turned[58] his head and looked at me and stopped. I at once halted, bringing my musket to a trail. I was afraid to fire for fear of missing my mark, my musket being inaccurate, so I reserved my fire for closer quarters, the bear being at least fifty yards from me, and he followed his course in a walk. I was surprised and said to myself,—"Old fellow, if you let me alone, I surely will not bother you."

I watched him 'till he was out of my sight. My reason for not shooting him was two-fold; first, I was afraid I might miss him, and my gun being a muzzle loader, the distance between us was too short, and he would have been on me before I could have reloaded, so I reserved my fire, expecting to get in closer proximity. I was agreeably surprised when he continued his journey. When I came to Monterey that afternoon, I told some of its citizens what a narrow escape I had. They smiled and said "Bears seldom attack human, unless in very great extremities, but I did well not to have shot unless I was sure that I would have killed him, for a wounded bear would stop the flow of blood with his fur, by tapping himself on the wound, and face his antagonist, and I could have been sure he would have gotten the best of me."

From Monterey I went over to McDowell, fourteen miles, to see my friend Eagle and his brother-in-law, Sanders, he that made the twelve Yankees run by running in front of them. I stated my business and invoked their assistance, which they cheerfully extended. In about three days, we had about as much as a four horse team could pull.

Provisions sold cheap. One could buy a fine turkey for fifty cents, a chicken for fifteen to twenty cents, butter twelve and one-half cents and everything else in proportion. Apples were given me for the gathering of them. Bacon and hams for seven to eight cents per pound, the finest cured I ever tasted.

The people in these regions lived bountifully, and always had an abundance to spare. Mr. Eagle furnished the team and accompanied me to camp, free of charge. Money was a scarce article at that time among the boys; the government was several months in arrear with our pay, but we expected to be paid off daily, so Mr. Eagle said he would be responsible to the parties that furnished the provisions, and the Company could pay him when we got our money; he was one of the most liberal and[60] patriotic men that it was my pleasure to meet during the war.

Four days later, Captain Jones received our money. I kept a record of all the provisions furnished to each man, and the captain deducted the amount from each. I wrote Eagle to come up and get his money; he came, and received every cent that was due him.

But I must not omit an incident that occurred when near our camp with the load of provisions. I had to pass hard by the Twelfth Georgia Regiment, which was camped on the side of the turn pike, when some of the men who were as anxious for a change of diet as we were, came to me and proposed to buy some of my provisions. I stated that they were sold and belonged to Company E, First Regiment, and that I could not dispose of them. Some Smart-Aleks, such as one may find among any gathering of men, proposed to charge the wagon and appropriate its contents by force. Seeing trouble ahead, I drew my pistol, when about a dozen men ran out with their guns. Eagle turned pale, he thought his time had come, when a Lieutenant interfered, asking the cause of the disturbance, which I stated. He said, "Men, none of that,[61] back with those guns." He mounted the wagon and accompanied us to my camp, which was a few hundred yards beyond.

Once later, I was called out for fatigue duty. I said, "Corporal, what is to be done?" He answered, "To cut wood for the blacksmith shop." I replied, "You had better get someone else who knows how, I never cut a stick in my life," he said, "You are not too old to learn how." This was conclusive, so he furnished me with an axe, and we marched into the woods, and he said he would be back directly with a wagon to get the wood and he left me. I was looking about me to find a tree, not too large, one that I thought I could manage. I spied a sugar maple about eight inches in diameter. I sent my axe into it, but did not take my cut large enough to reach the center, when it came down to a feather edge and I did not have judgment enough to know how to enlarge my cut by cutting from above, so I started a new cut from the right, another from the left, bringing the center to a pivot of about three inches in diameter, as solid as the Rock of Gibraltar; finally, by continuous hacking, I brought it to a point where I could push it back and forth. The momentum finally broke the center, but in place of falling, the top lodged in a neighboring tree,[63] and I could not dislodge it. I worked hard, the perspiration ran down my face, my hands were lacerated, I finally got mad, and sent the axe a-glimmering, and it slid under the snow. After awhile my corporal came for the wood; "Where is the wood?" I showed him the tree; "Is that all you have done?" I could not restrain any longer, I said, "Confound you, I told you I did not know anything about cutting wood." "Where is the axe?" We looked everywhere but could not find it; it must have slid under the snow and left no trace, so he arrested me and conducted me before Colonel Edward Johnson, a West Pointer, in command of the post. He was at his desk writing; turning to face us, he addressed himself to me, who stood there, cap in hand, while the Corporal stood there with his kept on his head. "What can I do for you?" I said, looking at the Corporal. "He has me under arrest and brought me here." Looking at the corporal the Colonel said, "Pull off your hat, sir, when you enter officers' quarters." (I would not have taken a dollar for that). The Corporal pulled off his cap. "What have you arrested him for?" The Corporal answered that I was regularly detailed to cut wood for the blacksmith shop, and that I failed to do my duty, and lost the axe he furnished me. "Why did[64] you not cut the wood?" said the Colonel. "I tried," said I, "I told him that I had never cut any wood and did not know how; where I came from there are no woods. Look at my hands." They were badly blistered and lacerated. The Colonel cursed out the Corporal as an imbecile, for not getting someone who was used to such work. I told the Colonel how hard I had tried and what I had done. The Colonel smiled and said, "What did you do with the axe?"; "When the tree lodged and I could not budge it, I got mad and made a swing or two with the axe, and let her slide; it must have slid under the snow, and we could not find it." "What have you done for a living?" "After I quit school, I clerked in a store." "Can you write?" "Oh, yes!" "Let me see." "My hand is too sore and hurt now." "Well, come around tomorrow, I may get you a job here."

Next day I called at his quarters, and he put me to copying some documents and reports, which I did to his satisfaction. I had warm quarters and was relieved from camp duties for a little while.

This brings us to about the middle of December, and we were ordered to Winchester. Colonel Johnson with his Regiment and a small[65] force, was left in charge of the Winter Quarters on the Allegheny, so I took leave of him to join my Company.

Colonel Johnson, while a little brusk in his demeanor, was a clever, social gentleman, and a good fighter, which he proved to be when the enemy made a night descent on him and took him by surprise. He rallied his men, barefooted in the snow, knee-deep, thrashed out the enemy and held the fort; he was promoted to General and was afterwards known as the Allegheny Johnson.

My Command having preceded me, I went to Staunton, where I met J. T. Youngblood, Robert Parnelle and others from my Company. I also met Lieutenant B. D. Evans of my Company, just returned from a visit from home. We took the stage coach from Stanton to Winchester through Kanawah Valley. We passed Woodstock, Strasburg, New Market, Middletown, and arrived at Winchester in due time. General T. J. Jackson in command, we had a splendid camp about a mile to the left of the city. The weather had greatly moderated and the snow was melting. The regiment had received tents to which we built chimneys with flat rocks that were abundant all around us. The[66] flour barrels served as chimney stacks, and we were comfortable; rations were also good and plentiful, but hardly were we installed when we received orders to strike camps. The men were greatly disappointed; we expected to be permitted to spend winter there. We took up the line of march late in the evening, marched all night and struck Bath early in the morning, took the enemy by surprise while they were fixing their morning meal, which they left, and the boys regaled themselves. The Commissary and Quartermaster also left a good supply behind in their rapid flight, and we appropriated many provisions, shoes, blankets and overcoats; from Bath we marched to Hancock, whipped out a small force of the enemy, and continued our force to Romney where we struck camps. Romney is a small town situated on the other side of the Potomac River. General Jackson demanded the surrender of the place, the enemy refused, so he ordered the non-combatants to leave, as he would bombard the town. Bringing up a large cannon which we called "Long Tom" owing to its size, he fired one round and ordered us to fall back. All this was during Christmas week.

On our return it turned very cold and sleeted;[67] the road became slick and frozen, and not being prepared for the emergency, I saw mules, horses and men take some of the hardest falls, as we retraced our steps, the road being down grade. This short campaign was a success and accomplished all it intended from a military standpoint, although we lost many men from exposure; pneumonia was prevalent among many of our men. We have now returned to Winchester. The writer himself, at that time, thought that this campaign was at a great sacrifice of lives from hardships and exposures, but later on, learned that it was intended as a check to enable General Lee in handling his forces against an overwhelming force of the enemy, and being still reinforced and whose battle cry still was "On to Richmond." It was for this reason that General "Stonewall" Jackson threatened Washington via Romney and the enemy had to recall their reinforcements intended against General Lee to protect Washington.

The men from the Southern States were not used to such rigorous climate and many of our men had to succumb from exposure. My Company lost three men from pneumonia, viz:—Sam and Richard Hines, two splendid soldiers,[68] and brothers, and Lorenzo Medlock. The writer also was incapacitated. There were no preparations in Winchester for such contingencies, so the churches were used as hospitals. The men were packed in the pews wrapped in their blankets, others were lying on the nasty humid floor, for it must be remembered that the streets in Winchester were perfect lobbies of dirt and snow tramped over by men, horses and vehicles. While there in that condition I had the good fortune to be noted by one of my regiment, he was tall and of herculean form, his name was Griswold, and while he and myself on a previous occasion had some misunderstanding and therefore not on speaking terms, he came to me and extended his hand, saying: "Let us be friends, we have hard times enough without adding to it." I was too sick to talk, but extended my hand, in token of having buried the hatchet. He asked me if he could do anything for me. I shook my head and shut my eyes. I was very weak. When I opened them he was gone. During the day he returned, saying: "I found a better place for you at a private house." He wrapped me in my blanket and carried me on his shoulders a distance of over three blocks. Mrs. Mandelbawm, the lady of the house, had a nice comfortable room prepared[69] for me, and Griswold waited on me like a brother, he was a powerful man, but very overbearing at times, but had a good heart. Mr. Mandelbawm sent their family physician, who prescribed for me. He pronounced me very sick, he did not know how it might terminate. It took all his efforts and my determination to get well after three weeks struggling to accomplish this end. My friend came to see me daily when off duty.

The regiment's term of enlistment will soon have expired, for we only enlisted for one year. The regiment received marching order, not being strong enough for duty. Through the recommendation of my doctor and regimental color, I was discharged and sent home. The regiment had been ordered to Tennessee, but owing to a wreck on the road they were disbanded at Petersburg, Va., and the boys arrived home ten days later than I.

In getting my transportation the Quartermaster asked me to deliver a package to General Beaureguard as I would pass via Manassas Junction. When I arrived I inquired for his quarters, when I was informed that he had left for Centreville, I followed to that place, when I was told he had left for Richmond. Arriving[70] at Richmond I went at once to the Executive Department in quest of him and should I fail to find him, would leave my package there, which I did. This was on Saturday evening, I had not a copper in money with me, but I had my pay roll; going at once to the Treasury Department, to my utter consternation, I found it closed. A very affable gentlemen informed me that the office was closed until Monday morning. I said, "What am I to do, I have not a cent of money in my pocket and no baggage," for at that time hotels had adopted a rule that guests without baggage would have to pay in advance. I remarked that I could not stay out in the streets, so the gentleman pulled a $10.00 bill out of his pocket and handed it to me saying, "Will that do you until Monday morning, 8 o'clock? When the office will be open, everything will be all right." I thanked him very kindly. Monday I presented my bill which was over six months in arrears. They paid it at once in Alabama State bills, a twenty-five cent silver and two cents coppers. I did not question the correctness of their calculation. I took the money and went in quest of my friend who so kindly advanced me the $10.00. I found him sitting at a desk. He was very busy. I handed him a $10.00 bill and again thanked him for his kindness; he refused[71] it saying: "Never mind, you are a long ways from home and may need it." I replied that I had enough to make out without it, I said that I appreciated it, but didn't like to take presents from strangers; he said, "We are no strangers, my name is Juda P. Benjamin." Mr. Benjamin was at that time Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederate States. He was an eminent lawyer from the State of Louisiana, he became later on Secretary of War, and when Lee surrendered he escaped to England to avoid the wrath of the Federal Officials who offered a premium for his capture. He became Queen's Consul in England and his reputation became international. No American who was stranded ever appealed to him in vain, especially those from the South. It is said of him that he gave away fortunes in charity.

I came back to Georgia among my friends who were proud to see me. Having no near relations, such as father or mother, sisters or brothers to welcome me, as had my comrades, my friends all over the County took pride in performing that duty, and thus ended my first year's experience as a soldier in the war between the States.

Notwithstanding the arduous campaign and severe hardships endured during my first year's service, I did not feel the least depressed in spirit or patriotism. On the contrary the arms of the Confederacy in the main had proven themselves very successful in repelling the enemy's attacks and forcing that government continually to call new levees to crush our forces in the field.

Those measures on the part of our adversaries appealed to every patriot at home and regardless of hardships already endured. Hence the First Georgia Regiment although disbanded as an organization, the rank and file had sufficient pluck to re-enter the service for the period of the war regardless as to how long it might last. Possessing some hard endured experience, many of them organized commands of their own, or joined other commands as subalterns or commissioned officers.

The following is a roll of promotion from the members of the Washington Rifles as first organized.—See Appendix D.

The foregoing record proves that the Washington Rifles were composed of men capable of handling forces and that it had furnished men[73] and officers in every branch of service in the Confederate States Army, and had been active after their return home from their first year's experience in raising no little army themselves, and what I have recorded of the Washington Rifles may be written of every Company composing the First Georgia Regiment.

The State of Georgia furnished more men than any other State, and Washington County furnished more Companies than any other County in the State.

Such men cannot be denominated as rebels or traitors, epithets that our enemies would fain have heaped upon us. If the true history of the United States as written before the war and adopted in every school-house in the land, North, South, East and West, did not demonstrate them as patriots, ready and willing to sacrifice all but honor on the altar of their country.

On the first of May, 1862, Sergeant E. P. Howell came to me saying: "Herman, how would you like to help me make up an artillery Company? I have a relative in South Carolina who is a West Pointer and understands that branch of the service. The Yankees are making tremendous efforts for new levees and we, of the South, have to meet them." "All right,"[74] said I, "I am tired after my experience with infantry, having gone through with 'Stonewall's' foot cavalry in his Romney campaign." The following day we made a tour in the neighborhood and enlisted a few of our old comrades in our enterprise. We put a notice in the Herald, a weekly paper edited by J. M. G. Medlock, that on the 10th day of May we would meet in Sandersville for organization, and then and there we formed an artillery Company that was to be known as the Sam Robinson Artillery Company, in honor of an old and venerable citizen of our County.

General Robinson, in appreciation of our having named the Company in his honor presented the organization with $1,000.00, which money was applied in uniforming us.

The following members formed the composite of said Company, and Robert Martin, known as "Bob Martin" from Barnwell, S. C., was elected Captain. See appendix E.

The writer was appointed bugler with rank of Sergeant.

That night after supper, it being moon-light, Mr. A. J. Linville a North Carolinian, a school teacher boarding at my lodging proposed to me as I performed on the flute, he being a violinist, to have some music on the water. He[75] then explained that water is a conductor of sound and that one could hear playing on it for a long distance and music would sound a great deal sweeter and more melodious than on land. The Ogeechee River ran within a couple of hundred yards from the house. There was on the bank and close to the bridge a party of gentlemen fishing, having a large camp fire and prepared to have a fish-fry, so Linville and myself took a boat that was moored above the bridge and quietly, unbeknown to anybody paddled about 1¼ mile up stream, expecting to float down with the current. Although it was the month of May the night was chilly enough for an overcoat. Linville and myself struck up a tune, allowing the boat to float along with the current, the oar laying across my lap. Everything was lovely, the moon was shining bright and I enjoyed the novelty of the surroundings and the music, when an over-hanging limb of a tree struck me on the neck. Wishing to disengage myself, I gave it a shove, and away went the boat from under me and I fell backwards into the stream in 12 feet of water. To gain the surface I had to do some hard kicking, my boots having filled with water and my heavy overcoat kept me weighted down.

When reaching the surface after a hard struggle my first observation was for the boat which was about 50 yards below, Linville swinging to a limb. I called him to meet me, and he replied that he had no oar, that I kicked it out of the boat. The banks on each side were steep and my effecting a landing was rather slim. I spied a small bush half-way up the embankment, I made for it perfectly exhausted, I grabbed it, the bank was too steep and slippery to enable me to land, so I held on and rested and managed to disembarrass myself of the overcoat and told Linville to hold on, that I was coming. I could not get my boots off, so I made an extra effort to reach him anyhow, as the current would assist me by being in my favor, so I launched off. I reached the boat perfectly worn out. I do not think I could have made another stroke. After a little breathing spell and by a tremendous effort I hoisted myself into the boat, but not before it dipped some water.