| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

JACOBITES (from Lat. Jacobus, James), the name given after the revolution of 1688 to the adherents, first of the exiled English king James II., then of his descendants, and after the extinction of the latter in 1807, of the descendants of Charles I., i.e. of the exiled house of Stuart.

The history of the Jacobites, culminating in the risings of 1715 and 1745, is part of the general history of England (q.v.), and especially of Scotland (q.v.), in which country they were comparatively more numerous and more active, while there was also a large number of Jacobites in Ireland. They were recruited largely, but not solely, from among the Roman Catholics, and the Protestants among them were often identical with the Non-Jurors. Owing to a variety of causes Jacobitism began to lose ground after the accession of George I. and the suppression of the revolt of 1715; and the total failure of the rising of 1745 may be said to mark its end as a serious political force. In 1765 Horace Walpole said that “Jacobitism, the concealed mother of the latter (i.e. Toryism), was extinct,” but as a sentiment it remained for some time longer, and may even be said to exist to-day. In 1750, during a strike of coal workers at Elswick, James III. was proclaimed king; in 1780 certain persons walked out of the Roman Catholic Church at Hexham when George III. was prayed for; and as late as 1784 a Jacobite rising was talked about. Northumberland was thus a Jacobite stronghold; and in Manchester, where in 1777 according to an American observer Jacobitism “is openly professed,” a Jacobite rendezvous known as “John Shaw’s Club” lasted from 1733 to 1892. North Wales was another Jacobite centre. The “Cycle of the White Rose”—the white rose being the badge of the Stuarts—composed of members of the principal Welsh families around Wrexham, including the Williams-Wynns of Wynnstay, lasted from 1710 until some time between 1850 and 1860. Jacobite traditions also lingered among the great families of the Scottish Highlands; the last person to suffer death as a Jacobite was Archibald Cameron, a son of Cameron of Lochiel, who was executed in 1753. Dr Johnson’s Jacobite sympathies are well known, and on the death of Victor Emmanuel I., the ex-king of Sardinia, in 1824, Lord Liverpool wrote to Canning saying “there are those who think that the ex-king was the lawful king of Great Britain.” Until the accession of King Edward VII. finger-bowls were not placed upon the royal dinner-table, because in former times those who secretly sympathized with the Jacobites were in the habit of drinking to the king over the water. The romantic side of Jacobitism was stimulated by Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley, and many Jacobite poems were written during the 19th century.

The chief collections of Jacobite poems are: Charles Mackay’s Jacobite Songs and Ballads of Scotland, 1688-1746, with Appendix of Modern Jacobite Songs (1861); G. S. Macquoid’s Jacobite Songs and Ballads (1888); and English Jacobite Ballads, edited by A. B. Grosart from the Towneley manuscripts (1877).

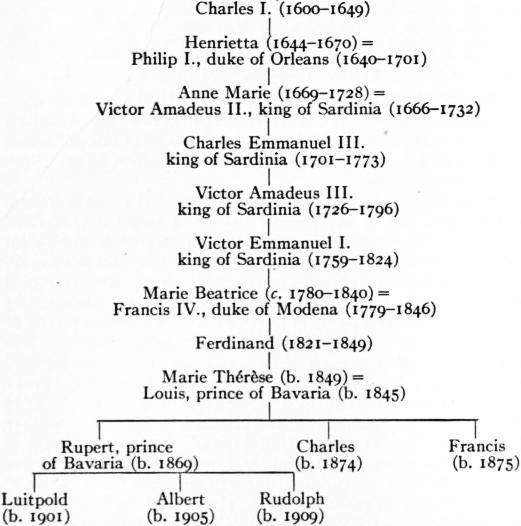

Upon the death of Henry Stuart, Cardinal York, the last of James II.’s descendants, in 1807, the rightful occupant of the British throne according to legitimist principles was to be found among the descendants of Henrietta, daughter of Charles I., who married Philip I., duke of Orleans. Henrietta’s daughter, Anne Marie (1669-1728), became the wife of Victor Amadeus II., duke of Savoy, afterwards king of Sardinia; her son was King Charles Emmanuel III., and her grandson Victor Amadeus III. The latter’s son, King Victor Emmanuel I., left no sons, and his eldest daughter, Marie Beatrice, married Francis IV., duke of Modena, 120 whose son Ferdinand (d. 1849) left an only daughter, Marie Thérèse (b. 1849). This lady, the wife of Prince Louis of Bavaria, was in 1910 the senior member of the Stuart family, and according to the legitimists the rightful sovereign of Great Britain and Ireland.

Table showing the succession to the crown of Great Britain and Ireland according to Jacobite principles.

Among the modern Jacobite, or legitimist, societies perhaps the most important is the “Order of the White Rose,” which has a branch in Canada and the United States. The order holds that sovereign authority is of divine sanction, and that the execution of Charles I. and the revolution of 1688 were national crimes; it exists to study the history of the Stuarts, to oppose all democratic tendencies, and in general to maintain the theory that kingship is independent of all parliamentary authority and popular approval. The order, which was instituted in 1886, was responsible for the Stuart exhibition of 1889, and has a newspaper, the Royalist. Among other societies with similar objects in view are the “Thames Valley Legitimist Club” and the “Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland.”

See Historical Papers relating to the Jacobite Period, edited by J. Allardyce (Aberdeen, 1895-1896); James Hogg, The Jacobite Relics of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1819-1821); and F. W. Head, The Fallen Stuarts (Cambridge, 1901). The marquis de Ruvigny has compiled The Jacobite Peerage (Edinburgh, 1904), a work which purports to give a list of all the titles and honours conferred by the kings of the exiled House of Stuart.

JACOBS, CHRISTIAN FRIEDRICH WILHELM (1764-1847), German classical scholar, was born at Gotha on the 6th of October 1764. After studying philology and theology at Jena and Göttingen, in 1785 he became teacher in the gymnasium of his native town, and in 1802 was appointed to an office in the public library. In 1807 he became classical tutor in the lyceum of Munich, but, disgusted at the attacks made upon him by the old Bavarian Catholic party, who resented the introduction of “north German” teachers, he returned to Gotha in 1810 to take charge of the library and the numismatic cabinet. He remained in Gotha till his death on the 30th of March 1847. Jacobs was an extremely successful teacher; he took great interest in the affairs of his country, and was a publicist of no mean order. But his great work was an edition of the Greek Anthology, with copious notes, in 13 volumes (1798-1814), supplemented by a revised text from the Codex Palatinus (1814-1817). He published also notes on Horace, Stobaeus, Euripides, Athenaeus and the Iliaca of Tzetzes; translations of Aelian (History of Animals); many of the Greek romances; Philostratus; poetical versions of much of the Greek Anthology; miscellaneous essays on classical subjects; and some very successful school books. His translation of the political speeches of Demosthenes was undertaken with the express purpose of rousing his country against Napoleon, whom he regarded as a second Philip of Macedon.

See E. F. Wüstemann, Friderici Jacobsii laudatio (Gotha, 1848); C. Bursian, Geschichte der classischen Philologie in Deutschland; and the appreciative article by C. Regel in Allgemeine deutsche Biographie.

JACOBS CAVERN, a cavern in latitude 36° 35′ N., 2 m. E. of Pineville, McDonald county, Missouri, named after its discoverer, E. H. Jacobs, of Bentonville, Arkansas. It was scientifically explored by him, in company with Professors Charles Peabody and Warren K. Moorehead, in 1903. The results were published in that year by Jacobs in the Benton County Sun; by C. N. Gould in Science, July 31, 1903; by Peabody in the Am. Anthropologist, Sept. 1903; and in the Am. Journ. Archaeology, 1904; and by Peabody and Moorehead, 1904, as Bulletin I. of the Dept. of Archaeology in Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass., in the museum of which are exhibits, maps and photographs.

Jacobs Cavern is one of the smaller caves, hardly more than a rock-shelter, and is entirely in the “St Joe Limestone” of the sub-carboniferous age. Its roof is a single flat stratum of limestone; its walls are well marked by lines of stratification; dripstone also partly covers the walls, fills a deep fissure at the end of the cave, and spreads over the floor, where it mingles with an ancient bed of ashes, forming an ash-breccia (mostly firm and solid) that encloses fragments of sandstone, flint spalls, flint implements, charcoal and bones. Underneath is the true floor of the cave, a mass of homogeneous yellow clay, one metre in thickness. It holds scattered fragments of limestone, and is itself the result of limestone degeneration. The length of the opening is over 21 metres; its depth 14 metres, and the height of roof above the undisturbed ash deposit varied from 1 m. 20 cm. to 2 m. 60 cm. The bone recess at the end was from 50 cm. to 80 cm. in height. The stratum of ashes was from 50 cm. to 1 m. 50 cm. thick.

The ash surface was staked off into square metres, and the substance carefully removed in order. Each stalactite, stalagmite and pilaster was measured, numbered, and removed in sections. Six human skeletons were found buried in the ashes. Seven-tenths of a cubic metre of animal bones were found: deer, bear, wolf, raccoon, opossum, beaver, buffalo, elk, turkey, woodchuck, tortoise and hog; all contemporary with man’s occupancy. Three stone metates, one stone axe, one celt and fifteen hammer-stones were found. Jacobs Cavern was peculiarly rich in flint knives and projectile points. The sum total amounts to 419 objects, besides hundreds of fragments, cores, spalls and rejects, retained for study and comparison. Considerable numbers of bone or horn awls were found in the ashes, as well as fragments of pottery, but no “ceremonial” objects.

The rude type of the implements, the absence of fine pottery, and the peculiarities of the human remains, indicate a race of occupants more ancient than the “mound-builders.” The deepest implement observed was buried 50 cm. under the stalagmitic surface. Dr. Hovey has proved that the rate of stalagmitic growth in Wyandotte Cave, Indiana, is .0254 cm. annually; and if that was the rate in Jacobs Cavern, 1968 years would have been needed for the embedding of that implement. Polished rocks outside the cavern and pictographs in the vicinity indicate the work of a prehistoric race earlier than the Osage Indians, who were the historic owners previous to the advent of the white man.

JACOBSEN, JENS PETER (1847-1885), Danish imaginative writer, was born at Thisted in Jutland, on the 7th of April 1847; he was the eldest of the five children of a prosperous merchant. He became a student at the university of Copenhagen in 1868. As a boy he showed a remarkable turn for science, particularly for botany. In 1870, although he was secretly writing verses already, Jacobsen definitely adopted botany as a profession. He was sent by a scientific body in Copenhagen to report on the flora of the islands of Anholt and Læsö. About this time the discoveries of Darwin began to exercise a fascination over him, and finding them little understood in Denmark, he translated into Danish The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man. In 121 the autumn of 1872, while collecting plants in a morass near Ordrup, he contracted pulmonary disease. His illness, which cut him off from scientific investigation, drove him to literature. He met the famous critic, Dr Georg Brandes, who was struck by his powers of expression, and under his influence, in the spring of 1873, Jacobsen began his great historical romance of Marie Grubbe. His method of composition was painful and elaborate, and his work was not ready for publication until the close of 1876. In 1879 he was too ill to write at all; but in 1880 an improvement came, and he finished his second novel, Niels Lyhne. In 1882 he published a volume of six short stories, most of them written a few years earlier, called, from the first of them, Mogens. After this he wrote no more, but lingered on in his mother’s house at Thisted until the 30th of April 1885. In 1886 his posthumous fragments were collected. It was early recognized that Jacobsen was the greatest artist in prose that Denmark has produced. He has been compared with Flaubert, with De Quincey, with Pater; but these parallelisms merely express a sense of the intense individuality of his style, and of his untiring pursuit of beauty in colour, form and melody. Although he wrote so little, and crossed the living stage so hurriedly, his influence in the North has been far-reaching. It may be said that no one in Denmark or Norway has tried to write prose carefully since 1880 whose efforts have not been in some degree modified by the example of Jacobsen’s laborious art.

His Samlede Skrifter appeared in two volumes in 1888; in 1899 his letters (Breve) were edited by Edvard Brandes. In 1896 an English translation of part of the former was published under the title of Siren Voices: Niels Lyhne, by Miss E. F. L. Robertson.

JACOB’S WELL, the scene of the conversation between Jesus and the “woman of Samaria” narrated in the Fourth Gospel, is described as being in the neighbourhood of an otherwise unmentioned “city called Sychar.” From the time of Eusebius this city has been identified with Sychem or Shechem (modern Nablus), and the well is still in existence 1½ m. E. of the town, at the foot of Mt Gerizim. It is beneath one of the ruined arches of a church mentioned by Jerome, and is reached by a few rough steps. When Robinson visited it in 1838 it was 105 ft. deep, but it is now much shallower and often dry.

For a discussion of Sychar as distinct from Shechem see T. K. Cheyne, art. “Sychar,” in Ency. Bibl., col. 4830. It is possible that Sychar should be placed at Tulūl Balātā, a mound about ½ m. W. of the well (Palestine Exploration Fund Statement, 1907, p. 92 seq.); when that village fell into ruin the name may have migrated to ’Askar, a village on the lower slopes of Mt Ebal about 1¾ m. E.N.E. from Nablus and ½ m. N. from Jacob’s Well. It may be noted that the difficulty is not with the location of the well, but with the identification of Sychar.

JACOBUS DE VORAGINE (c. 1230-c. 1298), Italian chronicler, archbishop of Genoa, was born at the little village of Varazze, near Genoa, about the year 1230. He entered the order of the friars preachers of St Dominic in 1244, and besides preaching with success in many parts of Italy, taught in the schools of his own fraternity. He was provincial of Lombardy from 1267 till 1286, when he was removed at the meeting of the order in Paris. He also represented his own province at the councils of Lucca (1288) and Ferrara (1290). On the last occasion he was one of the four delegates charged with signifying Nicholas IV.’s desire for the deposition of Munio de Zamora, who had been master of the order from 1285, and was deprived of his office by a papal bull dated the 12th of April 1291. In 1288 Nicholas empowered him to absolve the people of Genoa for their offence in aiding the Sicilians against Charles II. Early in 1292 the same pope, himself a Franciscan, summoned Jacobus to Rome, intending to consecrate him archbishop of Genoa with his own hands. He reached Rome on Palm Sunday (March 30), only to find his patron ill of a deadly sickness, from which he died on Good Friday (April 4). The cardinals, however, “propter honorem Communis Januae,” determined to carry out this consecration on the Sunday after Easter. He was a good bishop, and especially distinguished himself by his’ efforts to appease the civil discords of Genoa. He died in 1298 or 1299, and was buried in the Dominican church at Genoa. A story, mentioned by the chronicler Echard as unworthy of credit, makes Boniface VIII., on the first day of Lent, cast the ashes in the archbishop’s eyes instead of on his head, with the words, “Remember that thou art a Ghibelline, and with thy fellow Ghibellines wilt return to naught.”

Jacobus de Voragine left a list of his own works. Speaking of himself in his Chronicon januense, he says, “While he was in his order, and after he had been made archbishop, he wrote many works. For he compiled the legends of the saints (Legendae sanctorum) in one volume, adding many things from the Historia tripartita et scholastica, and from the chronicles of many writers.” The other writings he claims are two anonymous volumes of “Sermons concerning all the Saints” whose yearly feasts the church celebrates. Of these volumes, he adds, one is very diffuse, but the other short and concise. Then follow Sermones de omnibus evangeliis dominicalibus for every Sunday in the year; Sermones de omnibus evangeliis, i.e. a book of discourses on all the Gospels, from Ash Wednesday to the Tuesday after Easter; and a treatise called “Marialis, qui totus est de B. Maria compositus,” consisting of about 160 discourses on the attributes, titles, &c., of the Virgin Mary. In the same work the archbishop claims to have written his Chronicon januense in the second year of his pontificate (1293), but it extends to 1296 or 1297. To this list Echard adds several other works, such as a defence of the Dominicans, printed at Venice in 1504, and a Summa virtutum et vitiorum Guillelmi Peraldi, a Dominican who died about 1250. Jacobus is also said by Sixtus of Siena (Biblioth. Sacra, lib. ix.) to have translated the Old and New Testaments into his own tongue. “But,” adds Echard, “if he did so, the version lies so closely hid that there is no recollection of it,” and it may be added that it is highly improbable that the man who compiled the Golden Legend ever conceived the necessity of having the Scriptures in the vernacular.

His two chief works are the Chronicon januense and the Golden Legend or Lombardica hystoria. The former is partly printed in Muratori (Scriptores Rer. Ital. ix. 6). It is divided into twelve parts. The first four deal with the mythical history of Genoa from the time of its founder, Janus, the first king of Italy, and its enlarger, a second Janus “citizen of Troy”, till its conversion to Christianity “about twenty-five years after the passion of Christ.” Part v. professes to treat of the beginning, the growth and the perfection of the city; but of the first period the writer candidly confesses he knows nothing except by hearsay. The second period includes the Genoese crusading exploits in the East, and extends to their victory over the Pisans (c. 1130), while the third reaches down to the days of the author’s archbishopric. The sixth part deals with the constitution of the city, the seventh and eighth with the duties of rulers and citizens, the ninth with those of domestic life. The tenth gives the ecclesiastical history of Genoa from the time of its first known bishop, St Valentine, “whom we believe to have lived about 530 A.D.,” till 1133, when the city was raised to archiepiscopal rank. The eleventh contains the lives of all the bishops in order, and includes the chief events during their pontificates; the twelfth deals in the same way with the archbishops, not forgetting the writer himself.

The Golden Legend, one of the most popular religious works of the middle ages, is a collection of the legendary lives of the greater saints of the medieval church. The preface divides the ecclesiastical year into four periods corresponding to the various epochs of the world’s history, a time of deviation, of renovation, of reconciliation and of pilgrimage. The book itself, however, falls into five sections:—(a) from Advent to Christmas (cc. 1-5); (b) from Christmas to Septuagesima (6-30); (c) from Septuagesima to Easter (31-53); (d) from Easter Day to the octave of Pentecost (54-76); (e) from the octave of Pentecost to Advent (77-180). The saints’ lives are full of puerile legend, and in not a few cases contain accounts of 13th-century miracles wrought at special places, particularly with reference to the Dominicans. The last chapter but one (181), “De Sancto Pelagio Papa,” contains a kind of history of the world from the middle of the 6th century; while the last (182) is a somewhat allegorical disquisition, “De Dedicatione Ecclesiae.”

The Golden Legend was translated into French by Jean Belet de Vigny in the 14th century. It was also one of the earliest books to issue from the press. A Latin edition is assigned to about 1469; and a dated one was published at Lyons in 1473. Many other Latin editions were printed before the end of the century. A French translation by Master John Bataillier is dated 1476; Jean de Vigny’s appeared at Paris, 1488; an Italian one by Nic. Manerbi (? Venice, 1475); a Bohemian one at Pilsen, 1475-1479, and at Prague, 1495; Caxton’s English versions, 1483, 1487 and 1493; and a German one in 1489. Several 15th-century editions of the Sermons are also known, and the Mariale was printed at Venice in 1497 and at Paris in 1503.

For bibliography see Potthast, Bibliotheca hist. med. aev. (Berlin, 1896), p. 634; U. Chevalier, Répertoire des sources hist. Bio.-bibl. (Paris, 1905), s.v. “Jacques de Voragine.”

JACOTOT, JOSEPH (1770-1840), French educationist, author of the method of “emancipation intellectuelle,” was born 122 at Dijon on the 4th of March 1770. He was educated at the university of Dijon, where in his nineteenth year he was chosen professor of Latin, after which he studied law, became advocate, and at the same time devoted a large amount of his attention to mathematics. In 1788 he organized a federation of the youth of Dijon for the defence of the principles of the Revolution; and in 1792, with the rank of captain, he set out to take part in the campaign of Belgium, where he conducted himself with bravery and distinction. After for some time filling the office of secretary of the “commission d’organisation du mouvement des armées,” he in 1794 became deputy of the director of the Polytechnic school, and on the institution of the central schools at Dijon he was appointed to the chair of the “method of sciences,” where he made his first experiments in that mode of tuition which he afterwards developed more fully. On the central schools being replaced by other educational institutions, Jacotot occupied successively the chairs of mathematics and of Roman law until the overthrow of the empire. In 1815 he was elected a representative to the chamber of deputies; but after the second restoration he found it necessary to quit his native land, and, having taken up his residence at Brussels, he was in 1818 nominated by the Government teacher of the French language at the university of Louvain, where he perfected into a system the educational principles which he had already practised with success in France. His method was not only adopted in several institutions in Belgium, but also met with some approval in France, England, Germany and Russia. It was based on three principles: (1) all men have equal intelligence; (2) every man has received from God the faculty of being able to instruct himself; (3) everything is in everything. As regards (1) he maintained that it is only in the will to use their intelligence that men differ; and his own process, depending on (3), was to give any one learning a language for the first time a short passage of a few lines, and to encourage the pupil to study, first the words, then the letters, then the grammar, then the meaning, until a single paragraph became the occasion for learning an entire literature. After the revolution of 1830 Jacotot returned to France, and he died at Paris on the 30th of July 1840.

His system was described by him in Enseignement universel, langue maternelle, Louvain and Dijon, 1823—which passed through several editions—and in various other works; and he also advocated his views in the Journal de l’émancipation intellectuelle. For a complete list of his works and fuller details regarding his career, see Biographie de J. Jacotot, by Achille Guillard (Paris, 1860).

JACQUARD, JOSEPH MARIE (1752-1834), French inventor, was born at Lyons on the 7th of July 1752. On the death of his father, who was a working weaver, he inherited two looms, with which he started business on his own account. He did not, however, prosper, and was at last forced to become a lime-burner at Bresse, while his wife supported herself at Lyons by plaiting straw. In 1793 he took part in the unsuccessful defence of Lyons against the troops of the Convention; but afterwards served in their ranks on the Rhône and Loire. After seeing some active service, in which his young son was shot down at his side, he again returned to Lyons. There he obtained a situation in a factory, and employed his spare time in constructing his improved loom, of which he had conceived the idea several years previously. In 1801 he exhibited his invention at the industrial exhibition at Paris; and in 1803 he was summoned to Paris and attached to the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers. A loom by Jacques de Vaucanson (1700-1782), deposited there, suggested various improvements in his own, which he gradually perfected to its final state. Although his invention was fiercely opposed by the silk-weavers, who feared that its introduction, owing to the saving of labour, would deprive them of their livelihood, its advantages secured its general adoption, and by 1812 there were 11,000 Jacquard looms in use in France. The loom was declared public property in 1806, and Jacquard was rewarded with a pension and a royalty on each machine. He died at Oullins (Rhône) on the 7th of August 1834, and six years later a statue was erected to him at Lyons (see Weaving).

JACQUERIE, THE, an insurrection of the French peasantry which broke out in the Île de France and about Beauvais at the end of May 1358. The hardships endured by the peasants in the Hundred Years’ War and their hatred for the nobles who oppressed them were the principal causes which led to the rising, though the immediate occasion was an affray which took place on the 28th of May at the village of Saint-Leu between “brigands” (militia infantry armoured in brigandines) and countryfolk. The latter having got the upper hand united with the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages and placed Guillaume Karle at their head. They destroyed numerous châteaux in the valleys of the Oise, the Brèche and the Thérain, where they subjected the whole countryside to fire and sword, committing the most terrible atrocities. Charles the Bad, king of Navarre, crushed the rebellion at the battle of Mello on the 10th of June, and the nobles then took violent reprisals upon the peasants, massacring them in great numbers.

See Simeon Luce, Histoire de la Jacquerie (Paris, 1859 and 1895).

JACTITATION (from Lat. jactitare, to throw out publicly), in English law, the maliciously boasting or giving out by one party that he or she is married to the other. In such a case, in order to prevent the common reputation of their marriage that might ensue, the procedure is by suit of jactitation of marriage, in which the petitioner alleges that the respondent boasts that he or she is married to the petitioner, and prays a declaration of nullity and a decree putting the respondent to perpetual silence thereafter. Previously to 1857 such a proceeding took place only in the ecclesiastical courts, but by express terms of the Matrimonial Causes Act of that year it can now be brought in the probate, divorce and admiralty division of the High Court. To the suit there are three defences: (1) denial of the boasting; (2) the truth of the representations; (3) allegation (by way of estoppel) that the petitioner acquiesced in the boasting of the respondent. In Thompson v. Rourke, 1893, Prob. 70, the court of appeal laid down that the court will not make a decree in a jactitation suit in favour of a petitioner who has at any time acquiesced in the assertion of the respondent that they were actually married. Jactitation of marriage is a suit that is very rare.

JADE, or Jahde, a deep bay and estuary of the North Sea, belonging to the grand-duchy of Oldenburg, Germany. The bay, which was for the most part made by storm-floods in the 13th and 16th centuries, measures 70 sq. m., and has communication with the open sea by a fairway, a mile and a half wide, which never freezes, and with the tide gives access to the largest vessels. On the west side of the entrance to the bay is the Prussian naval port of Wilhelmshaven. A tiny stream, about 14 m. long, also known as the Jade, enters the head of the bay.

JADE, a name commonly applied to certain ornamental stones, mostly of a green colour, belonging to at least two distinct species, one termed nephrite and the other jadeite. Whilst the term jade is popularly used in this sense, it is now usually restricted by mineralogists to nephrite. The word jade1 is derived (through Fr. le jade for l’ejade) from Span. ijada (Lat. ilia), the loins, this mineral having been known to the Spanish conquerors of Mexico and Peru under the name of piedra de ijada or yjada (colic stone). The reputed value of the stone in renal diseases is also suggested by the term nephrite (so named by A. G. Werner from Gr. νεφρός, kidney), and by its old name lapis nephriticus.

Jade, in its wide and popular sense, has always been highly prized by the Chinese, who not only believe in its medicinal value but regard it as the symbol of virtue. It is known, with other ornamental stones, under the name of yu or yu-chi (yu-stone). According to Professor H. A. Giles, it occupies in China the highest place as a jewel, and is revered as “the quintessence of heaven and earth.” Notwithstanding its toughness or tenacity, due to a dense fibrous structure, it is wrought into complicated 123 forms and elaborately carved. On many prehistoric sites in Europe, as in the Swiss lake-dwellings, celts and other carved objects both in nephrite and in jadeite have not infrequently been found; and as no kind of jade had until recent years been discovered in situ in any European locality it was held, especially by Professor L. H. Fischer, of Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden, that either the raw material or the worked objects must have been brought by some of the early inhabitants from a jade locality probably in the East, or were obtained by barter, thus suggesting a very early trade-route to the Orient. Exceptional interest, therefore, attached to the discovery of jade in Europe, nephrite having been found in Silesia, and jadeite or a similar rock in the Alps, whilst pebbles of jade have been obtained from many localities in Austria and north Germany, in the latter case probably derived from Sweden. It is, therefore, no longer necessary to assign the old jade implements to an exotic origin. Dr A. B. Meyer, of Dresden, always maintained that the European jade objects were indigenous, and his views have become generally accepted. Now that the mineral characters of jade are better understood, and its identification less uncertain, it may possibly be found with altered peridotites, or with amphibolites, among the old crystalline schists of many localities.

Nephrite, or true jade, may be regarded as a finely fibrous or compact variety of amphibole, referred either to actinolite or to tremolite, according as its colour inclines to green or white. Chemically it is a calcium-magnesium silicate, CaMg3(SiO3)4. The fibres are either more or less parallel or irregularly felted together, rendering the stone excessively tough; yet its hardness is not great, being only about 6 or 6.5. The mineral sometimes tends to become schistose, breaking with a splintery fracture, or its structure may be horny. The specific gravity varies from 2.9 to 3.18, and is of determinative value, since jadeite is much denser. The colour of jade presents various shades of green, yellow and grey, and the mineral when polished has a rather greasy lustre. Professor F. W. Clarke found the colours due to compounds of iron, manganese and chromium. One of the most famous localities for nephrite is on the west side of the South Island of New Zealand, where it occurs as nodules and veins in serpentine and talcose rocks, but is generally found as boulders. It was known to the Maoris as pounamu, or “green stone,” and was highly prized, being worked with great labour into various objects, especially the club-like implement known as the mere, or pattoo-pattoo, and the breast ornament called hei-tiki. The New Zealand jade, called by old writers “green talc of the Maoris,” is now worked in Europe as an ornamental stone. The green jade-like stone known in New Zealand as tangiwai is bowenite, a translucent serpentine with enclosures of magnesite. The mode of occurrence of the nephrite and bowenite of New Zealand has been described by A. M. Finlayson (Quart. Jour. Geol. Soc., 1909, p. 351). It appears that the Maoris distinguished six varieties of jade. Difference of colour seems due to variations in the proportion of ferrous silicate in the mineral. According to Finlayson, the New Zealand nephrite results from the chemical alteration of serpentine, olivine or pyroxene, whereby a fibrous amphibole is formed, which becomes converted by intense pressure and movement into the dense nephrite.

Nephrite occurs also in New Caledonia, and perhaps in some of the other Pacific islands, but many of the New Caledonian implements reputed to be of jade are really made of serpentine. From its use as a material for axe-heads, jade is often known in Germany as Beilstein (“axe-stone”). A fibrous variety, of specific gravity 3.18, found in New Caledonia, and perhaps in the Marquesas, was distinguished by A. Damour under the name of “oceanic jade.”

Much of the nephrite used by the Chinese has been obtained from quarries in the Kuen-lun mountains, on the sides of the Kara-kash valley, in Turkestan. The mineral, generally of pale colour, occurs in nests and veins running through hornblende-schists and gneissose rocks, and it is notable that when first quarried it is comparatively soft. It appears to have a wide distribution in the mountains, and has been worked from very ancient times in Khotan. Nephrite is said to occur also in the Pamir region, and pebbles are found in the beds of many streams. In Turkestan, jade is known as yashm or yeshm, a word which appears in Arabic as yeshb, perhaps cognate with ἴασπις or jasper. The “jasper” of the ancients may have included jade. Nephrite is said to have been discovered in 1891 in the Nan-shan mountains in the Chinese province of Kan-suh, where it is worked. The great centre of Chinese jade-working is at Peking, and formerly the industry was active at Su-chow Fu. Siberia has yielded very fine specimens of dark green nephrite, notably from the neighbourhood of the Alibert graphite mine, near Batugol, Lake Baikal. The jade seems to occur as a rock in part of the Sajan mountain system. New deposits in Siberia were opened up to supply material for the tomb of the tsar Alexander III. A gigantic monolith exists at the tomb of Tamerlane at Samarkand. The occurrence of the Siberian jade has been described by Professor L. von Jaczewski.

Jade implements are widely distributed in Alaska and British Columbia, being found in Indian graves, in old shell-heaps and on the sites of deserted villages. Dr G. M. Dawson, arguing from the discovery of some boulders of jade in the Fraser river valley, held that they were not obtained by barter from Siberia, but were of native origin; and the locality was afterwards discovered by Lieut. G. M. Stoney. It is known as the Jade Mountains, and is situated north of Kowak river, about 150 miles from its mouth. The study of a large collection of jade implements by Professor F. W. Clarke and Dr G. P. Merrill proved that the Alaskan jade is true nephrite, not to be distinguished from that of New Zealand.

Jadeite is a mineral species established by A. Damour in 1863, differing markedly from nephrite in that its relation lies with the pyroxenes rather than with the amphiboles. It is an aluminium sodium silicate, NaAl(SiO3)2, related to spodumene. S. L. Penfield showed, by measurement, that jadeite is monoclinic. Its colour is commonly very pale, and white jadeite, which is the purest variety, is known as “camphor jade.” In many cases the mineral shows bright patches of apple-green or emerald-green, due to the presence of chromium. Jadeite is much more fusible than nephrite, and is rather harder (6.5 to 7), but its most readily determined character is found in its higher specific gravity, which ranges from 3.20 to 3.41. Some jadeite seems to be a metamorphosed igneous rock.

The Burmese jade, discovered by a Yunnan trader in the 13th century, is mostly jadeite. The quarries, described by Dr F. Noetling, are situated on the Uru river, about 120 m. from Mogaung, where the jadeite occurs in serpentine, and is partly extracted by fire-setting. It is also found as boulders in alluvium, and when these occur in a bed of laterite they acquire a red colour, which imparts to them peculiar value. According to Dr W. G. Bleeck, who visited the jade country of Upper Burma after Noetling, jadeite occurs at three localities in the Kachin Hills—Tawmaw, Hweka and Mamon. The jadeite is known as chauk-sen, and is sent either to China or to Mandalay, by way of Bhamo, whence Bhamo has come erroneously to be regarded as a locality for jade. Jadeite occurs in association with the nephrite of Turkestan, and possibly in some other Asiatic localities. In certain cases nephrite is formed by the alteration of jadeite, as shown by Professor J. P. Iddings. The Chinese feits’ui, sometimes called “imperial jade,” is a beautiful green stone, which seems generally to be jadeite, but it is said that in some cases it may be chrysoprase. It is named from its resemblance in colour to the plumage of the kingfisher. The resonant character of jade has led to its occasional use as a musical stone.

In Mexico, in Central America and in the northern part of South America, objects of jadeite are common. The Kunz votive adze from Oaxaca, in Mexico, is now in the American Museum of Natural History, New York. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico amulets of green stone were highly venerated, and it is believed that jadeite was one of the stones prized under the name of chalchihuitl. Probably turquoise was another stone included under this name, and indeed any green stone capable of being polished, such as the Amazon stone, now recognized as a green feldspar, may have been numbered among the Aztec amulets. Dr Kunz suggests that the chalchihuitl was jadeite in southern Mexico and Central America, and turquoise in northern Mexico and New Mexico. He thinks that Mexican jadeite may yet be discovered in places (Gems and Precious Stones of Mexico, by G. F. Kunz: Mexico, 1907).

Chloromelanite is Damour’s name for a dense, dark mineral which has been regarded as a kind of jade, and was used for the manufacture of celts found in the dolmens of France and in certain Swiss lake-dwellings. It is a mineral of spinach-green or dark-green colour, having a specific gravity of 3.4, or even as high as 3.65, and may be regarded as a variety of jadeite rich in iron. Chloromelanite occurs in the Cyclops Mountains in New Guinea, and is used for hatchets or agricultural implements, whilst the sago-clubs of the island are usually of serpentine. Sillimanite, or fibrolite, is a mineral which, like chloromelanite, was used by the Neolithic occupants of western Europe, and is sometimes mistaken for a pale kind of jade. It is an aluminium silicate, of specific gravity about 3.2, distinguished by its infusibility. The jade tenace of J. R. Haüy, discovered by H. B. de Saussure in the Swiss Alps, is now known as saussurite. Among other substances sometimes taken for jade may be mentioned prehnite, a hydrous calcium-aluminium silicate, which when polished much resembles certain kinds of jade. Pectolite has been used, like jade, in Alaska. A variety of vesuvianite (idocrase) from California, described by Dr. G. F. Kunz as californite, was at first mistaken for jade. The name jadeolite has been given by Kunz to a green chromiferous syenite from the jadeite mines of Burma. The mineral called bowenite, at one time supposed to be jade, is a hard and tough variety of serpentine. Some of the common Chinese ornaments imitating jade are carved in steatite or serpentine, while others are merely glass. The pâte de riz is a fine white glass. The so-called “pink jade” is mostly quartz, artificially coloured, and “black jade,” though sometimes mentioned, has no existence.

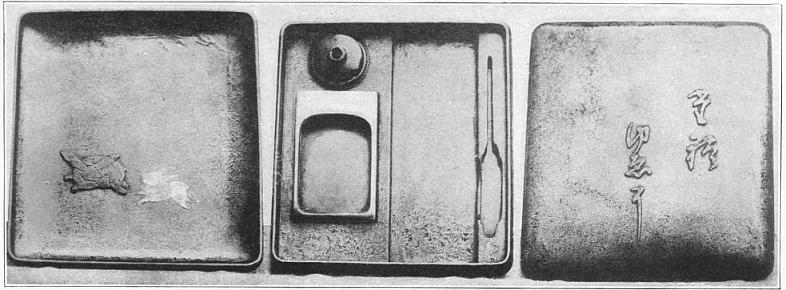

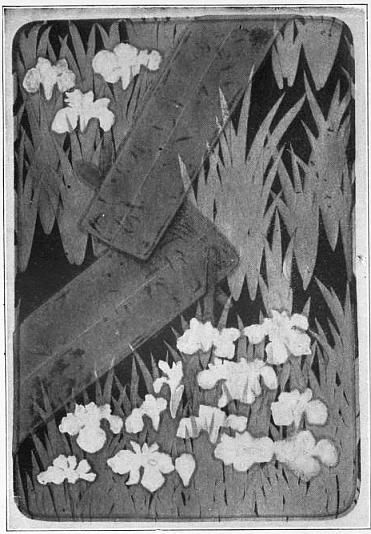

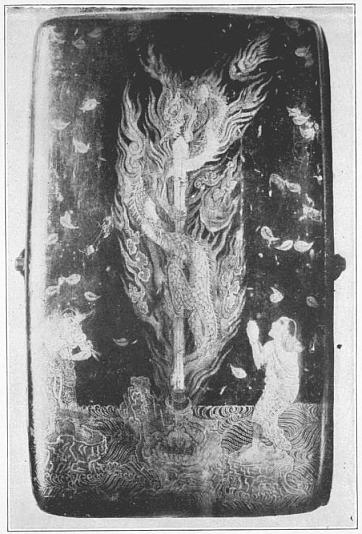

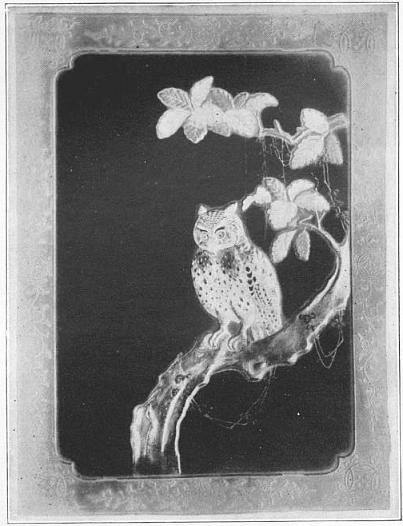

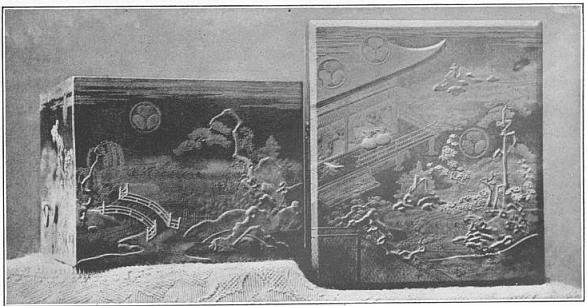

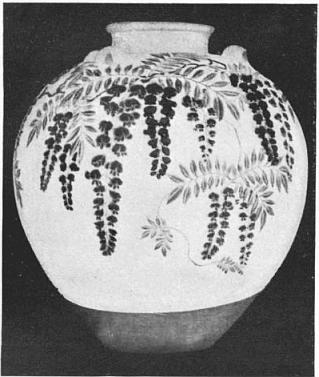

An exhaustive description of jade will be found in a sumptuous work, entitled Investigations and Studies in Jade (New York, 1906). This work, edited by Dr G. F. Kunz, was prepared in illustration of the famous jade collection made by Heber Reginald Bishop, and 124 presented by him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The work, which is in two folio volumes, superbly illustrated, was printed privately, and after 100 copies had been struck off on American hand-made paper, the type was distributed and the material used for the illustrations was destroyed. The second volume is a catalogue of the collection, which comprises 900 specimens arranged in three classes: mineralogical, archaeological and artistic. The important section on Chinese jade was contributed by Dr S. W. Bushell, who also translated for the work a discourse on jade—Yü-shuo by T’ang Jung-tso, of Peking. Reference should also be made to Heinrich Fischer’s Nephrit und Jadeit (2nd ed., Stuttgart, 1880), a work which at the date of its publication was almost exhaustive.

1 The English use of the word for a worthless, ill-tempered horse, a “screw,” also applied as a term of reproach to a woman, has been referred doubtfully to the same Spanish source as the O. Sp. ijadear, meaning to pant, of a broken-winded horse.

JAEN, an inland province of southern Spain, formed in 1833 of districts belonging to Andalusia; bounded on the N. by Ciudad Real and Albacete, E. by Albacete and Granada, S. by Granada, and W. by Cordova. Pop. (1900), 474,490; area, 5848 sq. m. Jaen comprises the upper basin of the river Guadalquivir, which traverses the central districts from east to west, and is enclosed on the north, south and east by mountain ranges, while on the west it is entered by the great Andalusian plain. The Sierra Morena, which divides Andalusia from New Castile, extends along the northern half of the province, its most prominent ridges being the Loma de Chiclana and the Loma de Ubeda; the Sierras de Segura, in the east, derive their name from the river Segura, which rises just within the border; and between the last-named watershed, its continuation the Sierra del Pozo, and the parallel Sierra de Cazorla, is the source of the Guadalquivir. The loftiest summits in the province are those of the Sierra Magina (7103 ft.) farther west and south. Apart from the Guadalquivir the only large rivers are its right-hand tributaries the Jándula and Guadalimar, its left-hand tributary the Guadiana Menor, and the Segura, which flows east and south to the Mediterranean.

In a region which varies so markedly in the altitude of its surface, the climate is naturally unequal; and, while the bleak, wind-swept highlands are only available as sheep-walks, the well-watered and fertile valleys favour the cultivation of the vine, the olive and all kinds of cereals. The mineral wealth of Jaen has been known since Roman times, and mining is an important industry, with its centre at Lináres. Over 400 lead mines were worked in 1903; small quantities of iron, copper and salt are also obtained. There is some trade in sawn timber and cloth; esparto fabrics, alcohol and oil are manufactured. The roads, partly owing to the development of mining, are more numerous and better kept than in most Spanish provinces. Railway communication is also very complete in the western districts, as the main line Madrid-Cordova-Seville passes through them and is joined south of Lináres by two important railways—from Algeciras and Malaga on the south-west, and from Almería on the south-east. The eastern half of Jaen is inaccessible by rail. In the western half are Jaen, the capital (pop. (1900), 26,434), with Andujar (16,302), Baeza (14,379), Bailen (7420), Lináres (38,245), Martos (17,078) and Ubeda (19,913). Other towns of more than 7000 inhabitants are Alcalá la Real, Alcaudete, Arjona, La Carolina and Porcuna, in the west; and Cazorla, Quesada, Torredonjimeno, Villacarillo and Villanueva del Arzobispo, in the east.

JAEN, the capital of the Spanish province of Jaen, on the Lináres-Puente Genil railway, 1500 ft. above the sea. Pop. (1900), 26,434. Jaen is finely situated on the well-wooded northern slopes of the Jabalcuz Mountains, overlooking the picturesque valleys of the Jaen and Guadalbullon rivers, which flow north into the Guadalquivir. The hillside upon which the narrow and irregular city streets rise in terraces is fortified with Moorish walls and a Moorish citadel. Jaen is an episcopal see. Its cathedral was founded in 1532; and, although it remained unfinished until late in the 18th century, its main characteristics are those of the Renaissance period. The city contains many churches and convents, a library, art galleries, theatres, barracks and hospitals. Its manufactures include leather, soap, alcohol and linen; and it was formerly celebrated for its silk. There are hot mineral springs in the mountains, 2 m. south.

The identification of Jaen with the Roman Aurinx, which has sometimes been suggested, is extremely questionable. After the Moorish conquest Jaen was an important commercial centre, under the name of Jayyan; and ultimately became capital of a petty kingdom, which was brought to an end only in 1246 by Ferdinand III. of Castille, who transferred hither the bishopric of Baeza in 1248. Ferdinand IV. died at Jaen in 1312. In 1712 the city suffered severely from an earthquake.

JAFARABAD, a state of India, in the Kathiawar agency of Bombay, forming part of the territory of the nawab of Janjira; area, 42 sq. m.; pop. (1901), 12,097; estimated revenue, £4000. The town of Jafarabad (pop. 6038), situated on the estuary of a river, carries on a large coasting trade.

JAFFNA, a town of Ceylon, at the northern extremity of the island. The fort was described by Sir J. Emerson Tennent as “the most perfect little military work in Ceylon—a pentagon built of blocks of white coral.” The European part of the town bears the Dutch stamp more distinctly than any other town in the island; and there still exists a Dutch Presbyterian church. Several of the church buildings date from the time of the Portuguese. In 1901 Jaffna had a population of 33,879, while in the district or peninsula of the same name there were 300,851 persons, nearly all Tamils, the only Europeans being the civil servants and a few planters. Coco-nut planting has not been successful of recent years. The natives grow palmyras freely, and have a trade in the fibre of this palm. They also grow and export tobacco, but not enough rice for their own requirements. A steamer calls weekly, and there is considerable trade. The railway extension from Kurunegala due north to Jaffna and the coast was commenced in 1900. Jaffna is the seat of a government agent and district judge, and criminal sessions of the supreme court are regularly held. Jaffna, or, as the natives call it, Yalpannan, was occupied by the Tamils about 204 B.C., and there continued to be Tamil rajahs of Jaffna till 1617, when the Portuguese took possession of the place. As early as 1544 the missionaries under Francis Xavier had made converts in this part of Ceylon, and after the conquest the Portuguese maintained their proselytizing zeal. They had a Jesuit college, a Franciscan and a Dominican monastery. The Dutch drove out the Portuguese in 1658. The Church of England Missionary Society began its work in Jaffna in 1818, and the American Missionary Society in 1822.

JÄGER, GUSTAV (1832- ), German naturalist and hygienist, was born at Bürg in Württemberg on the 23rd of June 1832. After studying medicine at Tübingen he became a teacher of zoology at Vienna. In 1868 he was appointed professor of zoology at the academy of Hohenheim, and subsequently he became teacher of zoology and anthropology at Stuttgart polytechnic and professor of physiology at the veterinary school. In 1884 he abandoned teaching and started practice as a physician in Stuttgart. He wrote various works on biological subjects, including Die Darwinsche Theorie und ihre Stellung zu Moral und Religion (1869), Lehrbuch der allgemeinen Zoologie (1871-1878), and Die Entdeckung der Seele (1878). In 1876 he suggested an hypothesis in explanation of heredity, resembling the germ-plasm theory subsequently elaborated by August Weismann, to the effect that the germinal protoplasm retains its specific properties from generation to generation, dividing in each reproduction into an ontogenetic portion, out of which the individual is built up, and a phylogenetic portion, which is reserved to form the reproductive material of the mature offspring. In Die Normalkleidung als Gesundheitsschutz (1880) he advocated the system of clothing associated with his name, objecting especially to the use of any kind of vegetable fibre for clothes.

JÄGERNDORF (Czech, Krnov), a town of Austria, in Silesia, 18 m. N.W. of Troppau by rail. Pop. (1900), 14,675, mostly German. It is situated on the Oppa and possesses a château belonging to Prince Liechtenstein, who holds extensive estates in the district. Jägerndorf has large manufactories of cloth, woollens, linen and machines, and carries on an active trade. On the neighbouring hill of Burgberg (1420 ft.) are a church, much visited as a place of pilgrimage, and the ruins of the seat of the former princes of Jägerndorf. The claim of Prussia to the principality of Jägerndorf was the occasion of the first Silesian war (1740-1742), but in the partition, which followed, Austria retained the larger portion of it. Jägerndorf suffered severely during the Thirty Years’ War, and was the scene of engagements between the Prussians and Austrians in May 1745 and in January 1779.

JAGERSFONTEIN, a town in the Orange Free State, 50 m. N.W. by rail of Springfontein on the trunk line from Cape Town to Pretoria. Pop. (1904), 5657—1293 whites and 4364 coloured persons. Jagersfontein, which occupies a pleasant situation on the open veld about 4500 ft. above the sea, owes its existence to the valuable diamond mine discovered here in 1870. The first diamond, a stone of 50 carats, was found in August of that year, and digging immediately began. The discovery a few weeks later of the much richer mines at Bultfontein and Du Toits Pan, followed by the great finds at De Beers and Colesberg Kop (Kimberley) caused Jagersfontein to be neglected for several years. Up to 1887 the claims in the mine were held by a large number of individuals, but coincident with the efforts to amalgamate the interest in the Kimberley mines a similar movement took place at Jagersfontein, and by 1893 all the claims became the property of one company, which has a working arrangement with the De Beers corporation. The mine, which is worked on the open system and has a depth of 450 ft., yields stones of very fine quality, but the annual output does not exceed in value £500,000. In 1909 a shaft 950 ft. deep was sunk with a view to working the mine on the underground system. Among the famous stones found in the mine are the “Excelsior” (weighing 971 carats, and larger than any previously discovered) and the “Jubilee” (see Diamond). The town was created a municipality in 1904.

Fourteen miles east of Jagersfontein is Boomplaats, the site of the battle fought in 1848 between the Boers under A. W. Pretorius and the British under Sir Harry Smith (see Orange Free State: History).

JAGO, RICHARD (1715-1781), English poet, third son of Richard Jago, rector of Beaudesert, Warwickshire, was born in 1715. He went up to University College, Oxford, in 1732, and took his degree in 1736. He was ordained to the curacy of Snitterfield, Warwickshire, in 1737, and became rector in 1754; and, although he subsequently received other preferments, Snitterfield remained his favourite residence. He died there on the 8th of May 1781. He was twice married. Jago’s best-known poem, The Blackbirds, was first printed in Hawkesworth’s Adventurer (No. 37, March 13, 1753), and was generally attributed to Gilbert West, but Jago published it in his own name, with other poems, in R. Dodsley’s Collection of Poems (vol. iv., 1755). In 1767 appeared a topographical poem, Edge Hill, or the Rural Prospect delineated and moralized; two separate sermons were published in 1755; and in 1768 Labour and Genius, a Fable. Shortly before his death Jago revised his poems, and they were published in 1784 by his friend, John Scott Hylton, as Poems Moral and Descriptive.

See a notice prefixed to the edition of 1784; A. Chalmers, English Poets (vol. xvii., 1810); F. L. Colvile, Warwickshire Worthies (1870); some biographical notes are to be found in the letters of Shenstone to Jago printed in vol. iii. of Shenstone’s Works (1769).

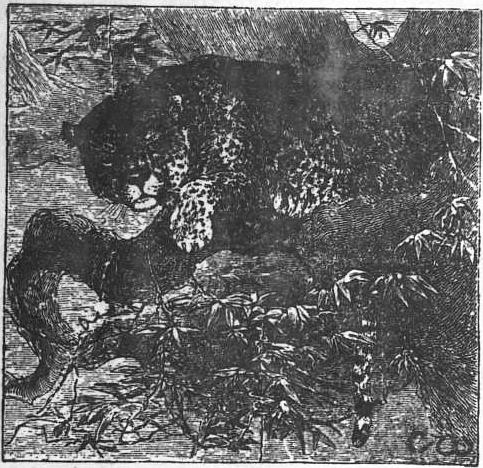

JAGUAR (Felis onca), the largest species of the Felidae found on the American continent, where it ranges from Texas through Central and South America to Patagonia. In the countries which bound its northern limit it is not frequently met with, but in South America it is quite common, and Don Felix de Azara states that when the Spaniards first settled in the district between Montevideo and Santa Fé, as many as two thousand were killed yearly. The jaguar is usually found singly (sometimes in pairs), and preys upon such quadrupeds as the horse, tapir, capybara, dogs or cattle. It often feeds on fresh-water turtles; sometimes following the reptiles into the water to effect a capture, it inserts a paw between the shells and drags out the body of the turtle by means of its sharp claws. Occasionally after having tasted human flesh, the jaguar becomes a confirmed man-eater. The cry of this great cat, which is heard at night, and most frequently during the pairing season, is deep and hoarse in tone, and consists of the sound pu, pu, often repeated. The female brings forth from two to four cubs towards the close of the year, which are able to follow their mother in about fifteen days after birth. The ground colour of the jaguar varies greatly, ranging from white to black, the rosette markings in the extremes being but faintly visible. The general or typical coloration is, however, a rich tan upon the head, neck, body, outside of legs, and tail near the root. The upper part of the head and sides of the face are thickly marked with small black spots, and the rest of body is covered with rosettes, formed of rings of black spots, with a black spot in the centre, and ranged lengthwise along the body in five to seven rows on each side. These black rings are heaviest along the back. The lips, throat, breast and belly, the inside of the legs and the lower sides of tail are pure white, marked with irregular spots of black, those on the breast being long bars and on the belly and inside of legs large blotches. The tail has large black spots near the root, some with light centres, and from about midway of its length to the tip it is ringed with black. The ears are black behind, with a large buff spot near the tip. The nose and upper lip are light rufous brown. The size varies, the total length of a very large specimen measuring 6 ft. 9 in.; the average length, however, is about 4 ft. from the nose to root of tail. In form the jaguar is thick-set; it does not stand high upon its legs; and in comparison with the leopard is heavily built; but its movements are very rapid, and it is fully as agile as its more graceful relative. The skull resembles that of the lion and tiger, but is much broader in proportion to its length, and may be identified by the presence of a tubercle on the inner edge of the orbit. The species has been divided into a number of local forms, regarded by some American naturalists as distinct species, but preferably ranked as sub-species or races.

|

| The Jaguar (Felis onca). |

JAGUARONDI, or Yaguarondi (Felis jaguarondi), a South American wild cat, found in Brazil, Paraguay and Guiana, ranging to north-eastern Mexico. This relatively small cat, uniformly coloured, is generally of some shade of brownish-grey, but in some individuals the fur has a rufous coat, while in others grey predominates. These cats are said by Don Felix de Azara to keep to cover, without venturing into open places. They attack tame poultry and also young fawns. The names jaguarondi and eyra are applied indifferently to this species and Felis eyra.

JAHANABAD, a town of British India in Gaya district, Bengal, situated on a branch of the East Indian railway. Pop. (1901), 7018. It was once a flourishing trading town, and in 1760 it formed one of the eight branches of the East India Company’s central factory at Patna. Since the introduction of Manchester goods, the trade of the town in cotton cloth has almost entirely ceased; but large numbers of the Jolaha or Mahommedan weaver caste live in the neighbourhood.

JAHANGIR, or Jehangir (1569-1627), Mogul emperor of Delhi, succeeded his father Akbar the Great in 1605. His name was Salim, but he assumed the title of Jahangir, “Conqueror of the World,” on his accession. It was in his reign that Sir Thomas Roe came as ambassador of James I., on behalf of the 126 English company. He was a dissolute ruler, much addicted to drunkenness, and his reign is chiefly notable for the influence enjoyed by his wife Nur Jahan, “the Light of the World.” At first she influenced Jahangir for good, but surrounding herself with her relatives she aroused the jealousy of the imperial princes; and Jahangir died in 1627 in the midst of a rebellion headed by his son, Khurram or Shah Jahan, and his greatest general, Mahabat Khan. The tomb of Jahangir is situated in the gardens of Shahdera on the outskirts of Lahore.

JĀḤIẒ (Abū ‘Uthmān ‘Amr Ibn Bahr ul-Jāḥiẓ; i.e. “the man the pupils of whose eyes are prominent”) (d. 869), Arabian writer. He spent his life and devoted himself in Basra chiefly to the study of polite literature. A Mu‘tazilite in his religious beliefs, he developed a system of his own and founded a sect named after him. He was favoured by Ibn uz-Zaiyāt, the vizier of the caliph Wāthiq.

His work, the Kitāb ul-Bayān wat-Tabyīn, a discursive treatise on rhetoric, has been published in two volumes at Cairo (1895). The Kitāb ul-Mahāsin wal-Addād was edited by G. van Vloten as Le Livre des beautés et des antithèses (Leiden, 1898); the Kitāb ul-Bu-halā. Le Livre des avares, ed. by the same (Leiden, 1900); two other smaller works, the Excellences of the Turks and the Superiority in Glory of the Blacks over the Whites, also prepared by the same. The Kitāb ul-Ḥayawān, or “Book of Animals,” a philological and literary, not a scientific, work, was published at Cairo (1906).

JAHN, FRIEDRICH LUDWIG (1778-1852), German pedagogue and patriot, commonly called Turnvater (“Father of Gymnastics”), was born in Lanz on the 11th of August 1778. He studied theology and philology from 1796 to 1802 at Halle, Göttingen and Greifswald. After Jena he joined the Prussian army. In 1809 he went to Berlin, where he became a teacher at the Gymnasium zum Grauen as well as at the Plamann School. Brooding upon the humiliation of his native land by Napoleon, he conceived the idea of restoring the spirits of his countrymen by the development of their physical and moral powers through the practice of gymnastics. The first Turnplatz, or open-air gymnasium, was opened by him at Berlin in 1811, and the movement spread rapidly, the young gymnasts being taught to regard themselves as members of a kind of gild for the emancipation of their fatherland. This patriotic spirit was nourished in no small degree by the writings of Jahn. Early in 1813 he took an active part at Breslau in the formation of the famous corps of Lützow, a battalion of which he commanded, though during the same period he was often employed in secret service. After the war he returned to Berlin, where he was appointed state teacher of gymnastics. As such he was a leader in the formation of the student Burschenschaften (patriotic fraternities) in Jena.

A man of democratic nature, rugged, honest, eccentric and outspoken, Jahn often came into collision with the reactionary spirit of the time, and this conflict resulted in 1819 in the closing of the Turnplatz and the arrest of Jahn himself. Kept in semi-confinement at the fortress of Kolberg until 1824, he was then sentenced to imprisonment for two years; but this sentence was reversed in 1825, though he was forbidden to live within ten miles of Berlin. He therefore took up his residence at Freyburg on the Unstrut, where he remained until his death, with the exception of a short period in 1828, when he was exiled to Cölleda on a charge of sedition. In 1840 he was decorated by the Prussian government with the Iron Cross for bravery in the wars against Napoleon. In the spring of 1848 he was elected by the district of Naumburg to the German National Parliament. Jahn died on the 15th of October 1852 in Freyburg, where a monument was erected in his honour in 1859.

Among his works are the following: Bereicherung des hochdeutschen Sprachschatzes (Leipzig, 1806), Deutsches Volksthum (Lübeck, 1810), Runenblätter (Frankfort, 1814), Neue Runenblätter (Naumburg, 1828), Merke zum deutschen Volksthum (Hildburghausen, 1833), and Selbstvertheidigung (Vindication) (Leipzig, 1863). A complete edition of his works appeared at Hof in 1884-1887. See the biography by Schultheiss (Berlin, 1894), and Jahn als Erzieher, by Friedrich (Munich, 1895).

JAHN, JOHANN (1750-1816), German Orientalist, was born at Tasswitz, Moravia, on the 18th of June 1750. He studied philosophy at Olmütz, and in 1772 began his theological studies at the Premonstratensian convent of Bruck, near Znaim. Having been ordained in 1775, he for a short time held a cure at Mislitz, but was soon recalled to Bruck as professor of Oriental languages and Biblical hermeneutics. On the suppression of the convent by Joseph II. in 1784, Jahn took up similar work at Olmütz, and in 1789 he was transferred to Vienna as professor of Oriental languages, biblical archaeology and dogmatics. In 1792 he published his Einleitung ins Alte Testament (2 vols.), which soon brought him into trouble; the cardinal-archbishop of Vienna laid a complaint against him for having departed from the traditional teaching of the Church, e.g. by asserting Job, Jonah, Tobit and Judith to be didactic poems, and the cases of demoniacal possession in the New Testament to be cases of dangerous disease. An ecclesiastical commission reported that the views themselves were not necessarily heretical, but that Jahn had erred in showing too little consideration for the views of German Catholic theologians in coming into conflict with his bishop, and in raising difficult problems by which the unlearned might be led astray. He was accordingly advised to modify his expressions in future. Although he appears honestly to have accepted this judgment, the hostility of his opponents did not cease until at last (1806) he was compelled to accept a canonry at St Stephen’s, Vienna, which involved the resignation of his chair. This step had been preceded by the condemnation of his Introductio in libros sacros veteris foederis in compendium redacta, published in 1804, and also of his Archaeologia biblica in compendium redacta (1805). The only work of importance, outside the region of mere philology, afterwards published by him, was the Enchiridion Hermeneuticae (1812). He died on the 16th of August 1816.

Besides the works already mentioned, he published Hebräische Sprachlehre für Anfänger (1792); Aramäische od. Chaldäische u. Syrische Sprachlehre für Anfänger(1793); Arabische Sprachlehre (1796); Elementarbuch der hebr. Sprache (1799); Chaldäische Chrestomathie (1800); Arabische Chrestomathie (1802); Lexicon arabico-latinum chrestomathiae accommodatum (1802); an edition of the Hebrew Bible (1806); Grammatica linguae hebraicae (1809); a critical commentary on the Messianic passages of the Old Testament (Vaticinia prophetarum de Jesu Messia, 1815). In 1821 a collection of Nachträge appeared, containing six dissertations on Biblical subjects. The English translation of the Archaeologia by T. C. Upham (1840) has passed through several editions.

JAHN, OTTO (1813-1869), German archaeologist, philologist, and writer on art and music, was born at Kiel on the 16th of June 1813. After the completion of his university studies at Kiel, Leipzig and Berlin, he travelled for three years in France and Italy; in 1839 he became privatdocent at Kiel, and in 1842 professor-extraordinary of archaeology and philology at Greifswald (ordinary professor 1845). In 1847 he accepted the chair of archaeology at Leipzig, of which he was deprived in 1851 for having taken part in the political movements of 1848-1849. In 1855 he was appointed professor of the science of antiquity, and director of the academical art museum at Bonn, and in 1867 he was called to succeed E. Gerhard at Berlin. He died at Göttingen, on the 9th of September 1869.

The following are the most important of his works: 1. Archaeological: Palamedes (1836); Telephos u. Troilos (1841); Die Gemälde des Polygnot (1841); Pentheus u. die Mänaden (1841); Paris u. Oinone (1844); Die hellenische Kunst (1846); Peitho, die Göttin der Überredung (1847); Über einige Darstellungen des Paris-Urteils (1849); Die Ficoronische Cista (1852); Pausaniae descriptio arcis Athenarum (3rd ed., 1901); Darstellungen griechischer Dichter auf Vasenbildern (1861). 2. Philological: Critical editions of Juvenal, Persius and Sulpicia (3rd ed. by F. Bücheler, 1893); Censorinus (1845); Florus (1852); Cicero’s Brutus (4th ed., 1877); and Orator (3rd ed., 1869); the Periochae of Livy (1853); the Psyche et Cupido of Apuleius (3rd ed., 1884; 5th ed., 1905); Longinus (1867; 3rd ed. by J. Vahlen, 1905). 3. Biographical and aesthetic: Üeber Mendelssohn’s Paulus (1842); Biographie Mozarts, a work of extraordinary labour, and of great importance for the history of music (3rd ed. by H. Disters, 1889-1891; Eng. trans. by P. D. Townsend, 1891); Ludwig Uhland (1863); Gesammelte Aufsätze über Musik (1866); Biographische Aufsätze (1866). His Griechische Bilderchroniken was published after his death, by his nephew A. Michaelis, who has written an 127 exhaustive biography in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, xiii.; see also J. Vahlen, Otto Jahn (1870); C. Bursian, Geschichte der classischen Philologie in Deutschland.

JAHRUM, a town and district of Persia in the province of Fars, S.E. of Shiraz and S.W. of Darab. The district has thirty-three villages and is famous for its celebrated sháhán dates, which are exported in great quantities; it also produces much tobacco and fruit. The water supply is scanty, and most of the irrigation is by water drawn from wells. The town of Jahrum, situated about 90 m. S.E. of Shiraz, is surrounded by a mud-wall 3 m. in circuit which was constructed in 1834. It has a population of about 15,000, one half living inside and the other half outside the walls. It is the market for the produce of the surrounding districts, has six caravanserais and a post office.

JAINS, the most numerous and influential sect of heretics, or nonconformists to the Brahmanical system of Hinduism, in India. They are found in every province of upper Hindustan, in the cities along the Ganges and in Calcutta. But they are more numerous to the west—in Mewar, Gujarat, and in the upper part of the Malabar coast—and are also scattered throughout the whole of the southern peninsula. They are mostly traders, and live in the towns; and the wealth of many of their community gives them a social importance greater than would result from their mere numbers. In the Indian census of 1901 they are returned as being 1,334,140 in number. Their magnificent series of temples and shrines on Mount Abu, one of the seven wonders of India, is perhaps the most striking outward sign of their wealth and importance.

The Jains are the last direct representatives on the continent of India of those schools of thought which grew out of the active philosophical speculation and earnest spirit of religious inquiry that prevailed in the valley of the Ganges during the 5th and 6th centuries before the Christian era. For many centuries Jainism was so overshadowed by that stupendous movement, born at the same time and in the same place, which we call Buddhism, that it remained almost unnoticed by the side of its powerful rival. But when Buddhism, whose widely open doors had absorbed the mass of the community, became thereby corrupted from its pristine purity and gradually died away, the smaller school of the Jains, less diametrically opposed to the victorious orthodox creed of the Brahmans, survived, and in some degree took its place.

Jainism purports to be the system of belief promulgated by Vaddhamāna, better known by his epithet of Mahā-vīra (the great hero), who was a contemporary of Gotama, the Buddha. But the Jains, like the Buddhists, believe that the same system had previously been proclaimed through countless ages by each one of a succession of earlier teachers. The Jains count twenty-four such prophets, whom they call Jinas, or Tīrthankaras, that is, conquerors or leaders of schools of thought. It is from this word Jina that the modern name Jainas, meaning followers of the Jina, or of the Jinas, is derived. This legend of the twenty-four Jinas contains a germ of truth. Mahā-vīra was not an originator; he merely carried on, with but slight changes, a system which existed before his time, and which probably owes its most distinguishing features to a teacher named Pārṣwa, who ranks in the succession of Jinas as the predecessor of Mahā-vīra. Pārṣwa is said, in the Jain chronology, to have been born two hundred years before Mahā-vīra (that is, about 760 B.C.); but the only conclusion that it is safe to draw from this statement is that Pārṣwa was considerably earlier in point of time than Mahā-vīra. Very little reliance can be placed upon the details reported in the Jain books concerning the previous Jinas in the list of the twenty-four Tīrthankaras. The curious will find in them many reminiscences of Hindu and Buddhist legend; and the antiquary must notice the distinctive symbols assigned to each, in order to recognize the statues of the different Jinas, otherwise identical, in the different Jain temples.

The Jains are divided into two great parties—the Digambaras, or Sky-clad Ones, and the Svetāmbaras, or the White-robed Ones. The latter have only as yet been traced, and that doubtfully, as far back as the 5th century after Christ; the former are almost certainly the same as the Nigaṇṭhas, who are referred to in numerous passages of the Buddhist Pāli Piṭakas, and must therefore be at least as old as the 6th century B.C. In many of these passages the Nigaṇṭhas are mentioned as contemporaneous with the Buddha; and details enough are given concerning their leader Nigaṇṭha Nāta-putta (that is, the Nigaṇṭha of the Jñātṛika clan) to enable us to identify him, without any doubt, as the same person as the Vaddhamāna Mahā-vīra of the Jain books. This remarkable confirmation, from the scriptures of a rival religion, of the Jain tradition is conclusive as to the date of Mahā-vīra. The Nigaṇṭhas are referred to in one of Asoka’s edicts (Corpus Inscriptionum, Plate xx.). Unfortunately the account of the teachings of Nigaṇṭha Nāta-putta given in the Buddhist scriptures are, like those of the Buddha’s teachings given in the Brahmanical literature, very meagre.

Jain Literature.—The Jain scriptures themselves, though based on earlier traditions, are not older in their present form than the 5th century of our era. The most distinctively sacred books are called the forty-five Āgamas, consisting of eleven Angas, twelve Upangas, ten Pakiṇṇakas, six Chedas, four Mūla-sūtras and two other books. Devaddhi Gaṇin, who occupies among the Jains a position very similar to that occupied among the Buddhists by Buddhaghosa, collected the then existing traditions and teachings of the sect into these forty-five Āgamas. Like the Buddhist scriptures, the earlier Jain books are written in a dialect of their own, the so-called Jaina Prākrit; and it was not till between A.D. 1000 and 1100 that the Jains adopted Sanskrit as their literary language. Considerable progress has been made in the publication and elucidation of these original authorities. But a great deal remains yet to be done. The oldest books now in the possession of the modern Jains purport to go back, not to the foundation of the existing order in the 6th century B.C., but only to the time of Bhadrabahu, three centuries later. The whole of the still older literature, on which the revision then made was based, the so-called Pūrvas, have been lost. And the existing canonical books, while preserving a great deal that was probably derived from them, contain much later material. The problem remains to sort out the older from the later, to distinguish between the earlier form of the faith and its subsequent developments, and to collect the numerous data for the general, social, industrial, religious and political history of India. Professor Weber gave a fairly full and carefully-drawn-up analysis of the whole of the more ancient books in the second part of the second volume of his Catalogue of the Sanskrit MSS. at Berlin, published in 1888, and in vols. xvi. and xvii. of his Indische Studien. An English translation of these last was published first in the Indian Antiquary, and then separately at Bombay, 1893. Professor Bhandarkar gave an account of the contents of many later works in his Report on the Search for Sanskrit MSS., Bombay, 1883. Only a small beginning has been made in editing and translating these works. The best précis of a long book can necessarily only deal with the more important features in it. And in the choice of what should be included the précis-writer will often omit the points some subsequent investigator may most especially want. All the older works ought therefore to be edited and translated in full and properly indexed. The Jains themselves have now printed in Bombay a complete edition of their sacred books. But the critical value of this edition, and of other editions of separate texts printed elsewhere in India, leaves much to be desired. Professor Jacobi has edited and translated the Kalpa Sūtra, containing a life of the founder of the Jain order; but this can scarcely be older than the 5th century of our era. He has also edited and translated the Āyāranya Sutta of the Svetambara Jains. The text, published by the Pali Text Society, is of 140 pages octavo. The first part of it, about 50 pages, is a very old document on the Jain views as to conduct, and the remainder consists of appendices, added at different times, on the same subject. The older part may go back as early as the 3rd century B.C., and it sets out more especially the Jain doctrine of tapas or self-mortification, in contradistinction to the Buddhist view, which condemned asceticism. The rules of conduct in this book are for members of the order. Dr Rudolf Hoernle edited and translated an ancient work on the rules of conduct for laymen, the Uvāsaga Dasāo.1 Professor Leumann edited another of the older works, the Aupapātika Sūtra, and a fourth, entitled the Dasa-vaikālika Sātra, both of them published by the German Oriental Society. Professor Jacobi translated two more, the Uttarādhyāyana and the Sūtra Kritānga.2 Finally Dr Barnett has translated two others in vol. xvii. of the Oriental Translation Fund (new series, London, 1907). Thus about one-fiftieth part of these interesting and valuable old records is now accessible to the European scholar. The sect of the Svetambaras has preserved the oldest literatures. Dr Hoernle has treated of the early history of 128 the sect in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal for 1898. Several scholars—notably Bhagvanlāl Indrajī, Mr Lewis Rice and Hofrath Bühler3—have treated of the remarkable archaeological discoveries lately made. These confirm the older records in many details, and show that the Jains, in the centuries before the Christian era, were a wealthy and important body in widely separated parts of India.

Jainism.—The most distinguishing outward peculiarity of Mahā-vīra and of his earliest followers was their practice of going quite naked, whence the term Digambara. Against this custom, Gotama, the Buddha, especially warned his followers; and it is referred to in the well-known Greek phrase, Gymnosophist, used already by Megasthenes, which applies very aptly to the Nigaṇṭhas. Even the earliest name Nigaṇṭha, which means “free from bonds,” may not be without allusions to this curious belief in the sanctity of nakedness, though it also alluded to freedom from the bonds of sin and of transmigration. The statues of the Jinas in the Jain temples, some of which are of enormous size, are still always quite naked; but the Jains themselves have abandoned the practice, the Digambaras being sky-clad at meal-time only, and the Svetāmbaras being always completely clothed. And even among the Digambaras it is only the recluses or Yatis, men devoted to a religious life, who carry out this practice. The Jain laity—the Srāvakas, or disciples—do not adopt it.