A History Handbook for

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

North Carolina and Tennessee

Produced by the

Division of Publications

National Park Service

U.S. Department of the Interior

Washington, D.C. 1984

This theme handbook, published in this new edition on the 50th anniversary of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, tells the story of the people who settled and lived in the mountains along the Tennessee and North Carolina border. Part 1 gives a brief introduction to the park and its historical sites. In Part 2, Wilma Dykeman and Jim Stokely present the history of the region from the early Cherokee days to the establishment of the park in 1934 and the renewed interest in the past in the 1970s; this text was first published by the National Park Service in 1978. Part 3 gives a brief description of the major historical buildings you can see in the park. For general information about the park and its wildlife, see Handbook 112.

National Park Handbooks, compact introductions to the great natural and historic places administered by the National Park Service, are published to support the National Park Service’s management programs at the parks and to promote understanding and enjoyment of the parks. This is Handbook 125.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Main entry under title: At home in the Smokies. (National park handbook; 125)

Rev. ed. of: Highland homeland/Wilma Dykeman and Jim Stokely. 1978. Includes index.

Supt. of Docs, no.: I 29.9/5:125

1. Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.)—Social life and customs. 2. Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.)—History. 3. Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.)—Guide-books. 4. Cherokee Indians—History.

I. Dykeman, Wilma. Highland homeland. II. United States. National Park Service. Division of Publications. III. Series: Handbook (United States. National Park Service. Division of Publications); 125.

F443.G7A8 1984 976.8’89 84-600108

ISBN 0-912627-22-0

| Part 1 | Recapturing the Past | 4 |

| Smoky Mountain Heritage | 7 | |

| Part 2 | Highland Homeland | 12 |

| By Wilma Dykeman and Jim Stokely | ||

| Homecoming | 17 | |

| Rail Fences | 30 | |

| Land of the Cherokees | 35 | |

| The Pioneers Arrive | 49 | |

| Rifle Making | 60 | |

| A Band of Cherokees Holds On | 63 | |

| From Pioneer to Mountaineer | 73 | |

| Spinning and Weaving | 94 | |

| The Sawmills Move In | 97 | |

| Birth of a Park | 107 | |

| The Past Becomes Present | 121 | |

| Handicrafts | 132 | |

| Coming Home | 137 | |

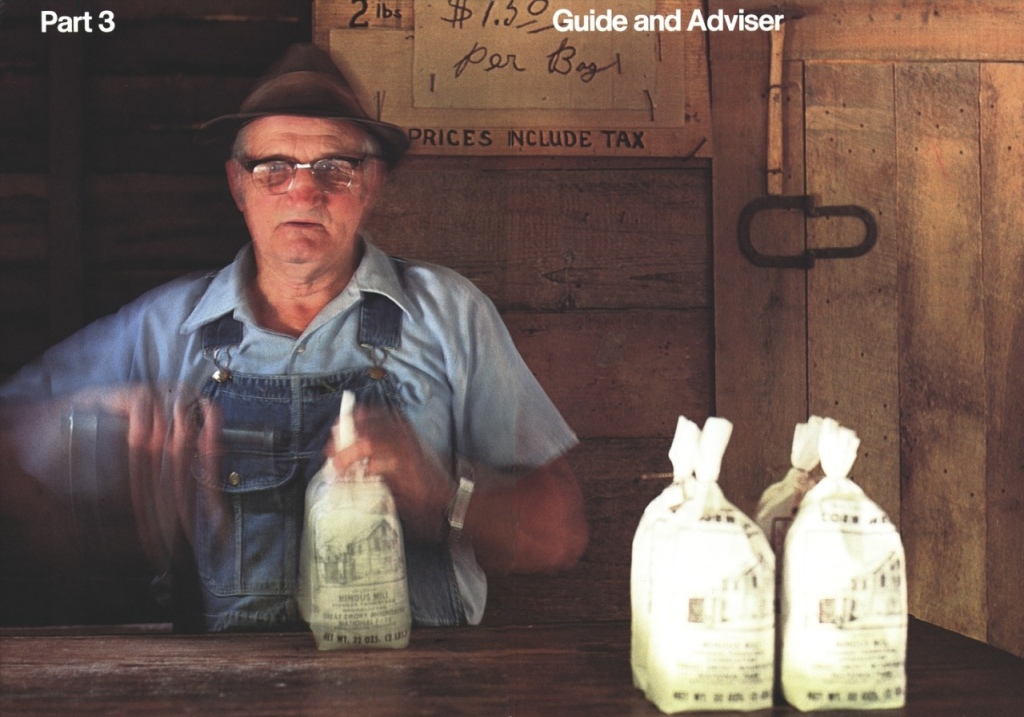

| Part 3 | Guide and Adviser | 146 |

| Traveling in the Smokies | 148 | |

| Oconaluftee | 150 | |

| Cades Cove | 152 | |

| Other Historic Sites in the Park | 154 | |

| Related Nearby Sites | 156 | |

| Armchair Explorations | 157 | |

| Index | 158 |

[Pg 4]

[Pg 5]

[Pg 6]

Joseph S. Hall

Aden Carver of Oconaluftee was a carpenter, stone mason, millwright, deacon, and preacher. He was more versatile than some men but representative of many who worked hard and enjoyed their lives in the Smokies.

[Pg 7]

Seemingly endless ridges, forests, mountain streams, waterfalls, and wildlife attract hundreds of thousands of travelers each year to Great Smoky Mountains National Park on the Tennessee-North Carolina border. Many are drawn by a long procession of wildflowers and shrubs bursting into bloom in the spring and by the colorful foliage of the hardwoods in the fall. Thousands hike the park’s many trails, which range from short spurs to the 110 kilometers (70 miles) of the Appalachian Trail that runs through the park. Also attracting wide interest are the park’s historical sites and the lifeways of the mountain people. They are pleasant surprises in the midst of all of nature’s richness. They are physical ties with our ancestors, many of whom traveled from their homelands across the sea to build new homes in the relatively unexplored continent of North America.

The National Park Service has preserved some of the historic structures in Great Smoky Mountains National Park so that we, and future generations, can better understand how our forefathers lived. By walking through and closely examining their finely crafted—and crudely crafted—log houses, barns, and other farm buildings we gain a new respect for their diligence and perseverance. The hours spent hewing massive beams, preserving foods for winter use, and making clothes from scratch are nearly incomprehensible in our age of machines and computers. The mountainous terrain demanded hard work, and the isolation fostered a zealous independence. The land truly molded a resourcefulness and hardiness in the Smokies character.

The story of these mountain people and communities is told in Part 2 of this handbook by Wilma Dykeman and Jim Stokely, who can look out on the expanse of the Great Smokies from their family home in Newport, Tennessee. Their engaging story of the Smokies is illustrated with historic photographs that largely come from the park’s files. Although the identities of many of the photographers are unknown (see page 160), we are no less indebted to them. They have helped to preserve the history and folkways of the Great Smokies people, who played a part in molding and defining our national character.

[Pg 8]

[Pg 9]

[Pg 10]

[Pg 11]

Charles S. Grossman

In the old days, housekeeping in the Smokies allowed few if any frills. Aunt Rhodie Abbott, and most other women, worked as hard as any man as they went about their daily chores keeping their families fed and clothed.

[Pg 12]

[Pg 13]

[Pg 14]

[Pg 15]

[Pg 16]

A home in the Smokies usually meant a simple log house nestled in the hills among the trees and amidst the haze.

National Park Service

[Pg 17]

It is summer now, a time for coming home. And on an August Sunday in the mountain-green valley they call Cataloochee, the kinfolk arrive. They come from 50 states to gather here, at a one-room white frame Methodist church by the banks of the Big “Catalooch.” The appearance of their shiny cars and bulky campers rolling along the paved Park Service road suggests that they are tourists, too, a tiny part of the millions who visit and enjoy the Great Smoky Mountains each year. Yet these particular families represent something more. A few of them were raised here; their ancestors lived and died here.

They are celebrating their annual Cataloochee homecoming. Other reunions, held on Sundays throughout the summer, bring together one-time residents of almost every area in the park. Some of the places instantly recall bits of history: Greenbrier, once a heavily populated cove and political nerve-center; Elkmont, where a blacksmith named Huskey set out one winter to cross the Smokies and was discovered dead in a bear trap the next spring; and Smokemont on the beautiful Oconaluftee River, at one time the home of the Middle Cherokee and the very heart of that Indian Nation.

These are special days, but they observe a universal experience as old as Homer’s Ulysses, as new as the astronauts’ return from the moon: homecoming. It is an experience particularly significant in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Here, at different times and in different ways, people of various races and heritage have reluctantly given up hearth and farm so that today new generations can come to this green kingdom of some 209,000 hectares (517,000 acres) and rediscover a natural homeland which is the heritage of all.

Beginning on Canada’s Gaspé Peninsula as a limestone finger only 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) wide, the Appalachian mountain system that dominates eastern America slants about 5,000 kilometers (3,000 miles) southwest across New England and the Atlantic and border states into northern Georgia and Alabama, culminating in the grandeur and complexity of the Great Smoky Mountains. This range, which marks the dividing line between Tennessee and North Carolina, is high; its 58-kilometer (36-mile) crest remains more than 1,500 meters (4,900 feet) above sea level. It is ancient—the Ocoee rocks here are estimated[Pg 18] to be 500-600 million years old—and its tall peaks and plunging valleys have been sculpted by nature through the action of ice and water during long, patient centuries. The odd and fantastic courses of the rivers here indicate that they are older than the mountains. The Great Smokies are a land of moving waters; there is no natural lake or pond in this area, but there are some 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) of streams with more than 70 species of fish. A generous rainfall, averaging as much as 229 centimeters (90 inches) per year in some localities and 211 centimeters (83 inches) atop Clingmans Dome, nourishes a rich variety of plantlife: more than 100 species of trees, 1,200 other flowering plants, 50 types of fern, 500 mosses and lichens, and 2,000 fungi. The mixed hardwood forest and virgin stands of balsam and spruce are the special glories of the Smokies.

Many of the species of birds that make the Smokies their home do not have to leave to migrate; by migrating vertically, from the valleys to the mountaintops in summer and back down in winter, they can experience the equivalent of a journey at sea level from Georgia to New England. Animals large and small find this a congenial home, and two, the wild boar and the black bear, are especially interesting to visitors. The former shuns people, but the latter is occasionally seen along trails and roadsides throughout the Smokies.

When the Great Smoky Mountains were added to the National Park System in 1934, a unique mission was accomplished: more than 6,600 separate tracts of land had been purchased by the citizens of Tennessee and North Carolina and given to the people of the United States. Previously, most national parks had been created from lands held by the Federal Government. The story of the Great Smokies is, therefore, most especially and significantly, a story of people and their home. Part of that story is captured in microcosm on an August Sunday in a secluded northeastern corner of the park: Cataloochee.

History is what the homecoming is about. The people of Cataloochee worship and sing and eat and celebrate because they are back. And being back, they remember. They walk up the narrow creeks, banked by thick tangles of rhododendron and dog-hobble, to the sites of old homesteads. They watch[Pg 19] their small children and grandchildren wade the water and trample the grass of once-familiar fields. They call themselves Caldwell, Palmer, Hannah, Woody, Bennett, Messer. For exactly a century—from the late 1830s and the coming of the first permanent white settlers to the later 1930s and the coming of the park—men and women with these names lived along Cataloochee Creek. But these pioneers were not the first to inhabit a valley that they called by an Indian name.

Alan Rinehart

With their trusty mule and sourwood sled, Giles and Lenard Ownby haul wood for making shingles.

By “Gad-a-lu-tsi,” the Cherokees meant “standing up in ranks.” As they looked from Cove Creek Gap at the eastern end of the valley across toward the Balsam Mountains, they used that term to describe the thin stand of timber at the top of the distant range. Later, the name became “Cataloochee,” or the colloquial “Catalooch,” and it referred to the entire watershed of the central stream.

The Cherokees liked what they saw. They hunted and fished throughout the area and established small villages along one of their main trails. The Cataloochee Track, as it came to be known, ran from Cove Creek Gap at the eastern edge of the present-day park up over the Smokies and down through what is now the Cosby section of eastern Tennessee. It connected large Indian settlements along the upper French Broad River in North Carolina with the equally important Overhill Towns of the Tennessee River.

By the early 1700s, Cataloochee formed a minor portion of the great Cherokee Nation whose towns and villages extended from eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina into northern Georgia. But as time went on, and as the white settlements pushed westward from the wide eastern front, the Cherokees lost dominion over this vast area. In 1791, at the treaty of Holston, the Cherokees gave up Cataloochee along with much of what is now East Tennessee. Five years later the state of North Carolina granted 71,210 hectares (176,000 acres), including all of Cataloochee, to John Gray Blount—brother to William Blount, governor of the Territory South of the Ohio River, as Tennessee was then called. Blount kept the land for speculation, but it eventually sold for less than one cent per hectare. Now that the Cherokees had relinquished the land, no one else seemed to want it. Even the famous Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury,[Pg 20] first sent as a missionary to America in 1771, apparently wavered in his spirit when confronted with the Cataloochee wilderness. In his journal in 1810 he lamented:

“At Catahouche I walked over a log. But O the mountain height after height, and five miles over! After crossing other streams, and losing ourselves in the woods, we came in, about nine o’clock at night.... What an awful day!”

During the 1820s, only a few hunters, trappers, and fishermen built overnight cabins in the area. Then in 1834, Col. Robert Love, who had migrated from Virginia, fought in the Revolutionary War, and established a farm near the present city of Asheville, purchased the original Blount tract for $3,000. To keep title to the land, Love was required to maintain permanent settlers there. He encouraged cattle ranging and permitted settlers choice locations and unlimited terms, and by the late 1830s several families had moved into Cataloochee. Probably the first settler to put down roots was young Levi Caldwell, a householder in his early twenties seeking a good home for his new family. The rich bottomlands and abundant forests of Cataloochee offered that home, and before Levi Caldwell died in 1864 at the age of 49, he and his wife “Polly” (Mary Nailling) had 11 children. Levi was a prisoner during the Civil War, and two of his sons, Andrew and William Harrison, fought on different sides. Because he had tended horses for the widely feared band of Union soldiers called Kirk’s Army, Andy received a $12 pension when the war was over. William, who might have forgiven and forgotten his differences with the Union as a whole, was never quite reconciled to his brother’s pension.

Although he was older than Levi Caldwell by a full 21 years, George Palmer arrived later at Catalooch. The Palmers had settled further northeast in the North Carolina mountains, on Sandy Mush Creek, and seemed content there. But when George decided to start over, he and his wife, also named Polly, took their youngest children, Jesse and George Lafayette, and crossed the mountains south into Cataloochee. They began again.

Edouard E. Exline

Cataloochee and Caldwell—the names are nearly synonymous. The Lush Caldwell family once lived in this sturdy log house with shake roof and stone chimneys on Messer Fork. At another time, this was the home of the E. J. Messers, another of Cataloochee’s predominant families.

Other families trickled in. As elsewhere in Southern Appalachia, buffalo traces and old Indian trails and more recent traders’ paths gradually became[Pg 21] roads and highways penetrating the thick forests and mountain fastnesses. In 1846, the North Carolina legislature passed an act creating the Jonathan Creek and Tennessee Mountain Turnpike Company, which was to build a road no less than 3.7 meters (12 feet) wide and no steeper than a 12 percent grade. Tolls would range from 75 cents for a six-horse wagon down to a dime for a man or a horse and one cent for each hog or sheep. After a full five years of deliberation and examining alternatives, the company selected a final route and constructed the highway with minor difficulty. The road fully utilized the natural contours of the land and was at the same time a generally direct line. It followed almost exactly the old Cherokee Trail.

The Cataloochee Turnpike was the first real wagon road in the Smokies. It opened up a chink in the area’s armor of isolation. Travel to and from the county seat still required the better part of three days, however. Two of the rare 19th century literary visitors to these mountains—Wilbur Zeigler and Ben Grosscup, whose book The Heart of the Alleghanies, appeared in 1883—entered Cataloochee along this road. Their reaction provides a pleasant contrast to that of Bishop Asbury; they speak of the “canon of the Cataluche” as being “the most picturesque valley of the Great Smoky range:”

“The mountains are timbered, but precipitous; the narrow, level lands between are fertile; farm houses look upon a rambling road, and a creek, noted as a prolific trout stream, runs a devious course through hemlock forests, around romantic cliffs, and between laureled banks.”

During the 1840s and 1850s, some 15 or 20 families built their sturdy log cabins ax-hewn out of huge chestnuts and poplars, and then built barns, smokehouses, corncribs, and other farm shelters beside the rocky creeks. George Palmer’s son Lafayette, called “Fate” for short, married one of Levi Caldwell’s daughters and established a large homestead by the main stream. Fate’s brother, Jesse, married and had 13 children; 6 of these 13 later married Caldwells.

[Pg 22]

[Pg 23]

Pages 22-23: These proud people all dressed up in their Sunday best are members of the George H. Caldwell family.

H. C. Wilburn

They ate well. The creek bottomlands provided rich soil for tomatoes, corn and beans, cabbage and onions, potatoes and pumpkins. Split rail fences were devices to keep the cattle, hogs, and sheep out of the crops; the animals themselves foraged freely throughout[Pg 24] the watershed, fattening on succulent grasses and an ample mast of acorns and chestnuts. Corn filled the cribs, salted pork and beef layered the meathouse, and cold bountiful springs watered the valley.

The Civil War erupted in 1861. Although Cataloochee lay officially in the Confederacy, this creek country was so remote, so distant from the slave plantations of the deep South, that no government dominated. Raiding parties from both sides rode through the valley, killing and looting as they went. Near Mt. Sterling Gap at the northern end of the watershed, Kirk’s Army made a man named Grooms play a fiddle before they murdered him. The people of Catalooch kept his memory alive throughout the century by playing that ill-starred “Grooms tune.”

But the war was only an interlude. Five years after its end, Cataloochee was estimated to have 500 hogs, sheep, milch cows, beef cattle, and horses; some 900 kilograms (2,000 pounds) of honey; and about 1,250 liters (1,320 quarts) of sorghum molasses. Sizable apple crops would begin to flourish during the next decade, and by 1900 the population of the valley would grow to over 700. Producing more than they themselves could use, these farmers began to trade with the outside world. They took their apples, livestock, chestnuts, eggs, honey, and ginseng to North Carolina markets in Fines Creek, Canton, and Waynesville, and to Tennessee outlets in Cosby, Newport, and Knoxville. With their cash money, they changed forever the Cataloochee of the early 1800s.

They sold honey and bought the tools of education. Using the tough, straight wood of a black gum or a basswood, a farmer hollowed out a section of the trunk with a chisel. He then slid a cross-stick through a hole bored near the bottom. Upon transplanting a beehive into the trunk and leaving an entrance at the bottom, he covered the top with a solid wooden lid and sealed it airtight with a mixture of mud and swamp-clay. In August, especially after the sourwoods had bloomed and the bees had built up a store of the delicately flavored honey, the beekeeper took a long hooked honey knife, broke the sealing, and cut out squares of the light golden comb to fill ten-gallon tins. He never went below the cross-stick; that honey was left for the bees. An enterprising[Pg 25] family might trade 10 tins of honey in a season. And at the market, they would turn that honey into school supplies for the coming year: shoes, books, tablets, and pencils.

[Pg 26]

Like many others in the Smokies, Dan Myers of Cades Cove kept a few bees. He apparently was a little more carefree than some about the tops of his bee gums, or hives. Some old boards or scraps of tin, with the help of a couple of rocks, sufficed, whereas most people sealed their wooden tops with a little mud.

Charles S. Grossman

There were too few families on Big Cataloochee for both a Methodist and a Baptist church. In 1858 Colonel Love’s son had deeded a small tract there for the Palmers, Bennetts, Caldwells, and Woodys to use as a Methodist meetinghouse and school. Since then, the Messers and Hannahs and several others had formed a community of their own 8 kilometers (5 miles) north, across Noland Mountain, along the smaller valley of the Little Cataloochee. They built a Baptist church there in 1890.

But the differences were not great. One of the Big Cataloochee’s sons became and remained the high sheriff of sprawling Haywood County with the well-nigh solid support of the combined Cataloochee vote. Running six times in succession and against a candidate from the southeastern part of the county, he was rumored to have waited each time for the more accessible lowlands to record their early returns. Then he simply contacted a cousin, who happened to be the recorder for Cataloochee, who would ask in his slow, easy voice, “How many do you need, cousin?”

The preacher came once a month. He stayed with different families in the community and met the rest at church. More informal gatherings, such as Sunday School and singings, took place each week. And during late summer or fall, when crops were “laid by” and there was an interval between spring’s cultivation and autumn’s harvest, there came the socializing and fervor of camp meeting. A one-week or ten-day revival was cause for school to be let out at 11 o’clock each morning. The children were required to attend long and fervent services. But between exhortations there were feasts of food, frolicking in nearby fields and streams, and for everyone an exchange of good fellowship.

Besides these religious gatherings, women held bean-stringings and quilting bees, men assembled for logrollings or house-raisings to clear new lands and build new homes. One of the few governmental intrusions into Cataloochee life was the road requirement. During the spring and fall, all able-bodied men were [Pg 27]“warned out” for six days—eight if there had been washout rains—to keep up what had become the well-used Cataloochee Turnpike. If a man brought a mule and a bull-tongue plow instead of the usual mattock, he received double time for ditching the sides of the road. This heavy work gave the men both a chance to talk and something to talk about. But any of them would still have said that the hardest job of the year was hoeing corn all day on a lonely, stony hillside.

By the early 1900s, Cataloochee had become a mixture of isolation from the outside world and communication with it. Outside laws had affected the valley; in 1885 North Carolina passed the controversial No Fence law, which made fences within townships unnecessary and required owners to keep cattle, sheep, horses, and hogs inside certain bounds. But other laws were less heeded; local experts have estimated that 95 percent of Cataloochee residents made their own whisky. Several families subscribed to a newspaper—“Uncle Jim” Woody took The Atlanta Constitution—and almost everyone possessed the “wish-book:” a dog-eared mail order catalog. But no one in Little Cataloochee bought an automobile.

The valley thrived on local incidents. A man shot a deputy sheriff and hid out near a large rock above Fate Palmer’s homestead; Neddy McFalls and Dick Clark fed him there for years. Will Messer, a master carpenter and coffinmaker over on Little Catalooch, had a daughter named Ola. Messer was postmaster, and the post office acquired her name. Fate Palmer’s shy son, Robert, became known as the “Booger Man” after he hid his face in his arms and gave that as his name to a new teacher on the first day of school.

George Palmer, son of Jesse and brother to Sheriff William, devised a method of capturing wild turkeys. He first built a log enclosure, then dug a trench under one side and baited it with corn. The next morning 10 turkeys, too frightened to retrace their steps through the trench, showed up inside the enclosure. But when George stepped among them and attempted to catch them, the turkeys gave him the beating of his life. Thereafter he was called “Turkey George.” And his daughter, Nellie, lent her name to one of the two post offices on Big Catalooch.

[Pg 28]

“Turkey George” Palmer of Pretty Hollow Creek in Cataloochee used to tell people that he had killed 105 bears. Most of them he trapped in bear pens.

Edouard E. Exline

Yet the simplicity of life could not insulate the Cataloochee area from “progress.” As the 20th century[Pg 29] unfolded, scattered individual loggers gave way to the well organized methods of large company operations. Small-scale cutting of yellow-tulip poplar and cherry boomed into big business during the early 1900s. Suncrest Lumber Company, with a sawmill in Waynesville, began operations on Cataloochee Creek and hauled out hardwood logs in great quantities. Although the spruce and balsam at the head of the watershed were left standing, the logging industry, with its capital, manpower, and influence, vastly altered the valley.

With the late 1920s came an announcement that the states of North Carolina and Tennessee had decided to give the Great Smoky Mountains to the nation as a park. The residents of Cataloochee were incredulous. They were attached to this homeplace; they still referred to a short wagon ride as a trip and called a visit to the county seat a journey. But the park arrived, and the young families of the valley moved away, and then the older ones did the same. Gradually they came to understand that another sort of homeland had been established. And the strangers who now visit their valleys and creeks can look about and appreciate the heritage these settlers and their descendants left behind.

The old families still come back. They return to this creek on the August Sunday of Homecoming. In the early morning hours they fill the wooden benches of tiny Palmer’s Chapel for singing and preaching and reminiscing; at noon they share bountiful food spread on long plank tables beside clear, rushing Cataloochee Creek; in the mellow afternoon they rediscover the valley. For what lures the stranger is what lures the old families back. They come to sense again the beauty and the permanence and even the foggy mystery of the Great Smokies. And this that beckons them back is that which beckoned the Indian discoverers of these mountains hundreds of years ago.

[Pg 30]

“Something there is that does not love a wall,” poet Robert Frost once wrote. Likewise, many mountain people felt something there is that does not love a fence. Fences were built for the purpose of keeping certain creatures out—and keeping other creatures in. During early days of settlement there were no stock-laws in the mountains. Cattle, mules, horses, hogs, sheep, and fowls ranged freely over the countryside. Each farmer had to build fences to protect his garden and crops from these domestic foragers as well as some of the wild “varmint” marauders. Rail fences had several distinct merits: they provided a practical use for some of the trees felled to clear crop and pasture land; they required little repair; they blended esthetically into the surroundings and landscape. Mountain fences have been described as “horse-high, bull-strong, and pig-tight.” W. Clark Medford, of North Carolina, has told us how worm fences (right) were built:

“There was no way to build a fence in those days except[Pg 31] with rails—just like there was no way to cover a house except with boards. First, they went into the woods, cut a good ‘rail tree’ and, with axes, wedge and gluts, split the cuts (of six-, eight- and ten-foot lengths as desired) into the rail. After being hauled to location, they were placed along the fence-way, which had already been cut out and made ready. Next, the ‘worm’ was laid. That is, the ground-rails were put down, end-on-end, alternating the lengths—first a long rail, then a short one—and so on through. Anyone who has seen a rail fence knows that the rails were laid end-on-end at angles—not at right angles, but nearly so. One course of rails after another would be laid up on the fence until it had reached the desired height (most fences were about eight rails high, some ten). Then, at intervals, the corners (where the rails lapped) would be propped with poles, and sometimes a stake would be driven. Such fences, when built of good chestnut or chestnut-oak rails, lasted for many years if kept from falling down.”

One of the most valuable fences ever constructed in the Smoky Mountains was surely that of Abraham Mingus. When “Uncle Abe,” one-time postmaster and miller, needed rails for fencing, he “cut into a field thick with walnut timber, split the tree bodies, and fenced his land with black walnut rails.”

The variety of fences was nearly infinite. Sherman Myers leans against a sturdy post and rider (below) near Primitive Baptist Church. Other kinds of fences are shown on the next two pages.

[Pg 32]

In this post and rider variation, rails are fastened to a single post with wire and staples.

National Park Service

Mary Birchfield of Cades Cove had an unusual fence with wire wound around crude pickets.

Charles S. Grossman

The Allisons of Cataloochee built a picket fence around their garden.

Charles S. Grossman

[Pg 33]

In the summer, farmers enclosed haystacks to keep grazing cattle away.

Charles S. Grossman

Ki Cable’s worm, or snake, fence in Cades Cove is one of the most common kinds of fencing.

Charles S. Grossman

Poles were used at John Oliver’s Cades Cove farm to line up the wall as it was built.

Charles S. Grossman

[Pg 34]

The plight of their Cherokee ancestors is revealed in the faces of Kweti and child in this photograph taken by James Mooney.

Smithsonian Institution

[Pg 35]

The Cherokees were among the first. They were the first to inhabit the Smokies, the first to leave them and yet remain behind. By the 1600s these Indians had built in the Southern Appalachians a Nation hundreds of years old, a way of life in harmony with the surrounding natural world, a culture richly varied and satisfying. But barely two centuries later, the newly formed government of the United States was pushing the Cherokees ever farther west. In the struggle for homeland, a new era had arrived: a time for the pioneer and for the settler from Europe and the eastern seaboard to stake claims to what seemed to them mere wilderness but which to the Cherokees was a physical and spiritual abode.

Perhaps it was during the last Ice Age that Indians drifted from Asia to this continent across what was then a land passage through Alaska’s Bering Strait. Finding and settling various regions of North America, this ancient people fragmented after thousands of years into different tribal and linguistic stocks. The Iroquois, inhabitants of what are now the North Central and Atlantic states, became one of the most distinctive of these stocks.

By the year 1000, the Cherokees, a tribe of Iroquoian origin, had broken off the main line and turned south. Whether wanting to or being pressured to, they slowly followed the mountain leads of the Blue Ridge and the Alleghenies until they reached the security and peace of the mist-shrouded Southern Appalachians. These “Mountaineers,” as other Iroquois called them, claimed an empire of roughly 104,000 square kilometers (40,000 square miles). Bounded on the north by the mighty Ohio River, it stretched southward in a great circle through eight states, including half of South Carolina and almost all of Kentucky and Tennessee.

Cherokee settlements dotted much of this territory, particularly in eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, and northern Georgia. These state regions are the rough outlines of what came to be the three main divisions of the Cherokee Nation: the Lower settlements on the headwaters of the Savannah River in Georgia and South Carolina; the Middle Towns on the Little Tennessee and Tuckasegee rivers in North Carolina; and the Overhill Towns with a capital on the Tellico River in Tennessee.

Between the Middle and the Overhill Cherokee,[Pg 36] straddling what is now the North Carolina-Tennessee line, lay the imposing range of the Great Smoky Mountains. Except for Mt. Mitchell in the nearby Blue Ridge, these were the highest mountains east of the Black Hills in South Dakota and the Rockies in Colorado. They formed the heart of the territorial Cherokee Nation. The Oconaluftee River, rushing down to the Tuckasegee from the North Carolina side of the Smokies, watered the homesites and fields of many Cherokees. Kituwah, a Middle Town near the present-day Deep Creek campground, may have been in the first Cherokee village.

National Park Service

Adventurers were drawn to the Great Smoky Mountains and the surrounding area in the 18th century. In 1760 a young British agent from Virginia, Lt. Henry Timberlake, journeyed far into Cherokee country. He observed Indian life and even sketched a map of the Overhill territory, complete with Fort Loudoun, “Chote” or Echota, and the “Enemy Mountains.”

For the most part, however, the Cherokees settled only in the foothills of the Smokies. Like the later pioneers, the Cherokees were content with the fertile lands along the rivers and creeks. But more than contentment was involved. Awed by this tangled wilderness, the Indians looked upon these heights as something both sacred and dangerous. One of the strongest of the old Cherokee myths tells of a race of spirits living there in mountain caves. These handsome “Little People” were usually helpful and kind, but they could make the intruder lose his way.

If the Cherokees looked up to the Smokies, they aimed at life around them with a level eye. Although the Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto and his soldiers ventured through Cherokee country in 1540 and chronicled generally primitive conditions, a Spanish missionary noted 17 years later that the Cherokees appeared “sedate and thoughtful, dwelling in peace in their native mountains; they cultivated their fields and lived in prosperity and plenty.”

They were moderately tall and rather slender with long black hair and sometimes very light complexions. They wore animal skin loincloths and robes, moccasins and a knee-length buckskin hunting shirt. A Cherokee man might dress more gaudily than a woman, but both enjoyed decorating their bodies extravagantly, covering themselves with paint and, as trade with whites grew and flourished, jewelry.

The tepee of Indian lore did not exist here. The Cherokee house was a rough log structure with one door and no windows. A small hole in the bark roof allowed smoke from a central fire to escape. Furniture and decorations included cane seats and painted hemp rugs. A good-sized village might number 40 or 50 houses.

[Pg 37]

Chota, in the Overhill country on the Little Tennessee River, was a center of civil and religious authority; it was also known as a “Town of Refuge,” a place of asylum for Indian criminals, especially murderers. The Smokies settlement of Kituwah served as a “Mother Town,” or a headquarters, for one of the seven Cherokee clans.

These clans—Wolf, Blue, Paint, Bird, Deer, Long Hair, and Wild Potato—were basic to the social structure of the tribe. The Cherokees traced their kinship by clan; marriage within clans was forbidden. And whereas the broad divisions of Lower, Middle, and Overhill followed natural differences in geography and dialect, the clans assumed great political significance. Each clan selected its own chiefs and its own “Mother Town.” Although one or two persons in Chota might be considered symbolic leaders, any chief’s powers were limited to advice and persuasion.

The Cherokees extended this democratic tone to all their towns. Each village, whether built along or near a stream or surrounded by protective log palisades, would have as its center a Town House and Square. The Square, a level field in front, was used for celebrations and dancing. The Town House itself sheltered the town council, plus the entire village, during their frequent meetings. In times of decision-making, as many as 500 people crowded into the smoky, earth-domed building where they sat in elevated rows around the council and heard debates on issues from war to the public granary.

Democracy was the keynote of the Cherokee Nation. “White” chiefs served during peacetime; “Red” chiefs served in time of war. Priests once formed a special class, but after an episode in which one of the priests attempted to “take” the wife of the leading chief’s brother, all such privileged persons were made to take their place alongside—not in front of—the other members of the community.

Women enjoyed the same status in Cherokee society as men. Clan kinship, land included, followed the mother’s side of the family. Although the men hunted much of the time, they helped with some household duties, such as sewing. Marriages were solemnly negotiated. And it was possible for women to sit in the councils as equals to men. Indeed, Nancy Ward, one of those equals who enjoyed the rank of Beloved Woman, did much to strengthen bonds of friendship between Cherokee and white during the turbulent years of the mid-18th century. The Irishman James Adair, who traded with the Cherokees during the years 1736 to 1743, even accused these Indians of “petticoat government.” Yet he must have found certain attractions in this arrangement, for he himself married a Cherokee woman of the Deer Clan.

[Pg 38]

Smithsonian Institution

A Cherokee fishes in the Oconaluftee River.

Charles S. Grossman

A team of oxen hauls a sled full of corn stalks for a Cherokee farmer near Ravensford, North Carolina. Oxen were more common beasts of burden in the mountains than horses mainly because they were less expensive.

[Pg 39]

Adair, an intent observer of Indian life, marveled at the Cherokees’ knowledge of nature’s medicines: “I do not remember to have seen or heard of an Indian dying by the bite of a snake, when out at war, or a hunting ... they, as well as all other Indian nations, have a great knowledge of specific virtues in simples: applying herbs and plants, on the most dangerous occasions, and seldom if ever, fail to effect a thorough cure, from the natural bush.... For my own part, I would prefer an old Indian before any surgeon whatsoever....”

[Pg 40]

[Pg 41]

Pages 40-41: At Ayunini’s house a woman pounds corn into meal with a mortar and pestle. The simple, log house is typical of Cherokee homes at the turn of the century. This one has stone chimneys, whereas many merely had a hole in the roof.

The Indians marveled at nature itself. A Civil War veteran remarked that the Cherokees “possess a keen and delicate appreciation of the beautiful in nature.” Most of their elaborate mythology bore a direct relation to rock and plant, animal and tree, river and sky. One myth told of a tortoise and a hare. The tortoise won the race, but not by steady plodding. He placed his relatives at intervals along the course; the hare, thinking the tortoise was outrunning him at every turn, wore himself out before the finish.

The Cherokees’ many myths and their obedience to nature required frequent performance of rituals. There were many nature celebrations, including three each corn season: the first at the planting of this staple crop, the second at the very beginning of the harvest, the third and last and largest at the moment of the fullest ripening. One of the most important rites, the changing of the fire, inaugurated each new year. All flames were extinguished and the hearths were swept clean of ashes. The sacred fire at the center of the Town House was then rekindled.

One ritual aroused particular enthusiasm: war. Battles drew the tribe together, providing an arena for fresh exploits and a common purpose and source of inspiration for the children. The Cherokees, with their spears, bows and arrows, and mallet-shaped clubs, met any challenger: Shawnee, Tuscarora, Creek, English, or American. In 1730, Cherokee chiefs told English emissaries: “Should we make[Pg 42] peace with the Tuscaroras ... we must immediately look for some other with whom we can be engaged in our beloved occupation.” Even in peacetime, the Cherokees might invade settlements just for practice.

But when the white man came, the struggle was for larger stakes. In 1775 William Bartram, the first able native-born American botanist, could explore the dangerous Cherokee country and find artistry there, perfected even in the minor arts of weaving and of carving stone tobacco pipes. He could meet and exchange respects with the famous Cherokee statesman Attakullakulla, also known as the Little Carpenter. And yet, a year later, other white men would destroy more than two-thirds of the settled Cherokee Nation.

Who were these fateful newcomers? Most of them were Scotch-Irish, a distinctive and adventuresome blend of people transplanted chiefly from the Scottish Lowlands to Northern Ireland during the reign of James I. Subsequently they flocked to the American frontier in search of religious freedom, economic opportunity, and new land they could call their own.

In the late 1600s, while the English colonized the Atlantic seaboard in North and South Carolina and Virginia, while the French settled Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana ports on the Gulf of Mexico, and while the Spanish pushed into Florida, 5,000 Presbyterian Scots left England for “the Plantation” in Northern Ireland. But as they settled and prospered, England passed laws prohibiting certain articles of Irish trade, excluding Presbyterians from civil and military offices, even declaring their ministers liable to prosecution for performing marriages.

The Scotch-Irish, as they were then called, found such repression unbearable and fled in the early 18th century to ports in Delaware and Pennsylvania. With their influx, Pennsylvania land prices skyrocketed. Poor, rocky soil to the immediate west turned great numbers of these Scotch-Irish southward down Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and along North Carolina’s Piedmont plateau. From 1732 to 1754, the population of North Carolina more than doubled. Extravagant stories of this new and fertile land also drew many from the German Palatinate to America; during the middle 1700s these hardworking “Pennsylvania Dutch” poured into the southern colonies.

[Pg 43]

Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia were colonies of the crown, and the Scotch-Irish and Germans intermarried with the already settled British. These Englishmen, of course, had their own reasons for leaving their more conservative countrymen in the mother country and starting a whole new life. Some were adventurers eager to explore a different land, some sought religious freedom, not a few were second sons—victims of the law of primogeniture—who arrived with hopes of building new financial empires of their own. They all confronted the frontier.

They encountered the Cherokee Nation and its vast territory. Earliest relations between the Cherokees and the pioneers were, to say the least, marked by paradox. Traders like James Adair formed economic ties and carried on a heavy commerce of guns for furs, whisky for blankets, jewelry for horses. But there was also deep resentment. The English colonies, especially South Carolina, even took Indian prisoners and sold them into slavery.

The Spanish had practiced this kind of slavery, arguing that thus the Indians would be exposed to the boon of Christianity. The English colonies employed what were known as “indentured servants,” persons who paid off the cost of their passage to America by working often as hard as slaves. And in later years both the white man and some of the more prosperous Cherokees kept Negro slaves. Such instances in the Nation were more rare than not, however, and a Cherokee might work side by side with any slave he owned; marriage between them was not infrequent. Be that as it may, the deplorable colonial policy of enforced servitude at any level, which continued into the late 1700s, sowed seeds of bitterness that ended in a bloody harvest.

Like the pioneers, the Cherokees cherished liberty above all else and distrusted government. Both left religion to the family and refused to institute any orthodox system of belief. Even the forms of humor were often parallel; the Cherokee could be as sarcastic as the pioneer and used irony to correct behavior. As one historian put it: “The coward was praised for his valor; the liar for his veracity; and the thief for his honesty.” But through the ironies of history, the Scotch-Irish-English-German pioneers of the highlands, who were similar to the Cherokees in a multitude of ways and quite different from the lowland[Pg 44] aristocrats, became the Indians’ worst enemy.

Their conflict was, in a sense, inevitable. The countries of England and France and their representatives in America both battled and befriended the Cherokees during the 18th century. Their main concern lay in their own rivalry, not in any deep-founded argument with the Indians. As they expanded the American frontier and immersed themselves in the process of building a country, the colonists inevitably encroached upon the Cherokee Nation.

Smithsonian Institution

In 1730, Sir Alexander Cuming took seven Cherokee leaders to England in an attempt to build up good relations with the tribe. Among the group was the youth Ukwaneequa (right), who was to become the great Cherokee chief Attakullakulla.

In 1730, in a burst of freewheeling diplomacy, the British sent a flamboyant and remarkable representative, Sir Alexander Cuming, into remote Cherokee country on a mission of goodwill. After meeting with the Indians on their own terms and terrain, Cuming arranged a massive public relations campaign and escorted Attakullakulla and six other Cherokee leaders to London, where they were showered with gifts and presented at court to King George II. The Cherokees allied themselves with Britain, but this did not discourage the French from trying to win their allegiance. When the English in 1743 captured a persuasive visionary named Christian Priber who sought to transform the Cherokee Nation into a socialist utopia, they suspected him of being a French agent and took him to prison in Frederica, Georgia. He was left to die in the fort.

The British soldiers were not as friendly as British diplomats. During the French and Indian War of the late 1750s and the early 1760s, when England battled France for supremacy in the New World, English soldiers treated the Cherokees with disdain and violence. The Cherokees returned the atrocities in kind. The frontier blazed with death and destruction; each side accumulated its own collection of horrors endured and meted out. Although Cherokee chiefs sued for peace, Gov. William Henry Lyttleton of South Carolina declared war on them in 1759. The Carolinas offered 25 English pounds for every Indian scalp. A year later the Cherokees, under the command of Oconostota, captured Fort Loudoun at the fork of the Tellico and Little Tennessee rivers. But in June of 1761, Capt. James Grant and some 2,600 men destroyed the Nation’s Middle Towns, burning 600 hectares (1,500 acres) of corn, beans, and peas, and forcing 5,000 Cherokees into the forests for the winter.

[Pg 45]

After the English defeated the French in 1763, the British government moved to appease the Indians and consolidate its control of the continent. A British proclamation forbade all white settlement beyond the Appalachian divide. But the proclamation was soon to be broken. Pioneers such as Daniel Boone and James Robertson successfully led their own and neighbors’ families through Appalachian gaps and river valleys until a trickle of explorers became a flood of homesteaders. During the next decade, settlers poured across the mountains into Kentucky and northeastern Tennessee.

While England was regaining the friendship of the Cherokees, the American colonists were alienating both the Indians and the British. In the late 1760s a group of North Carolinians calling themselves Regulators opposed taxation, land rents, and extensive land grants to selected individuals, and caused unrest throughout the Piedmont. In 1771, at Alamance, an estimated 2,000 Regulators were defeated by the troops of British Gov. William Tryon. Thousands of anti-royalist North Carolinians fled westward as a result of this battle. Alexander Cameron, an English representative living in the Overhill Towns, wrote in 1766 that the pioneer occupation of Cherokee lands amounted to an infestation by villains and horse thieves that was “enough to create disturbances among the most Civilized Nations.”

The protest spirit of the Regulators spread to the New England colonies during the early 1770s. By 1776, when the American Revolution began, the Cherokees had understandably but unfortunately chosen to take the British side. Britain issued guns to all Indians and offered rewards for American scalps, yet this was not enough to secure the over-mountain territory for the English crown. Within a year, American forces were fighting for the frontier, and in a coordinated pincer movement, Col. Samuel Jack with 200 Georgians, Gen. Griffith Rutherford with 2,400 North Carolinians, Col. Andrew Williamson with 1,800 South Carolinians, and Col. William Christian with 2,000 Virginians demolished more than 50 Cherokee towns. Two treaties resulted from this campaign; more than 2 million hectares (5 million acres) of Indian land, including northeastern Tennessee, much of South Carolina, and all lands east of the Blue Ridge, were ceded to the United States.

[Pg 46]

Ayunini, or Swimmer, was a medicine man. He was a major source of information about Cherokee history, mythology, botany, and medicine when James Mooney of the Bureau of American Ethnology visited the area in 1888.

Smithsonian Institution

[Pg 47]

Peace did not follow the treaties, however. Dragging Canoe, pock-marked son of Attakullakulla, decided to fight. Against the wishes of many Cherokee chiefs, he organized a renegade tribe that moved to five Lower Towns near present-day Chattanooga where they became known as the Chickamaugas. But the eventual outcome of the drama had already been determined. Despite conflict and danger, the settlers pushed on. In 1780 the Tennesseans John Sevier and Isaac Shelby joined forces with those of William Campbell from Virginia and Joseph McDowell from North Carolina and managed to win a decisive victory over the English at Kings Mountain, South Carolina. By fighting Indian-style on rugged hillside terrain, they overwhelmed a detachment of General Cornwallis’ southern forces under Col. Patrick Ferguson. These over-mountain men immediately returned to Tennessee and in reprisal for Indian raids during their absence destroyed Chota and nine other Overhill Towns, slaughtering women and children as well as Cherokee warriors.

In 1783, with the end of the Revolution, all hope for the survival of the original Cherokee Nation was extinguished. Although the newly formed American government attempted to conciliate the Indians, it could not prevent its own citizens from hungering for ever larger bites of land. Treaties with the loose Cherokee confederation of clans became more and more frequent. As if by fate, a disastrous smallpox epidemic struck the Cherokees; the number of warriors dwindled to less than half of what it had been 50 years before. The Cherokee capital was moved from Chota southward into Georgia. In 1794 Maj. James Ore and 550 militiamen from Nashville, Tennessee, obliterated the Chickamaugas and their Five Towns.

Most of the Cherokees parted with the Smokies. At the Treaty of Holston in 1791, they gave up the northeastern quarter of what is now the park. Seven years later, they ceded a southern strip. And at Washington, D.C., in February of 1819, nearly a century after their first treaty with the white man in 1721, the Cherokees signed their 21st treaty. This time they parted with a quarter of their entire Nation, and they lost the rest of their sacred Smoky Mountains. Scattered families continued to live in the foothills. But the newcomer—this pioneer turned settler—had arrived.

[Pg 48]

Between her many had-to-be-done tasks around the house, Mollie McCarter Ogle rocks her daughter Mattie on the porch.

Laura Thornborough

[Pg 49]

Into the Smokies they came, but the coming was slow. The early pioneers of the Old Southwest had conquered the lowlands of North Carolina and Tennessee with relative ease. The higher country of the Great Smoky Mountains, set into the Southern Appalachians like a great boulder among scattered stones, would yield less quickly.

The pioneers began, as the Cherokees had done, with the most accessible land. The level Oconaluftee valley, stretching its timbered swath from present-day Cherokee, North Carolina, on up into the forks and tributaries of the Great Smokies, beckoned with at least some possibilities to the hopeful settler. As early as 1790, Dr. Joseph Dobson, a North Carolina Revolutionary War veteran who had accompanied Rutherford on his 1777 campaign against the Cherokees, entered into deed a tract on the Oconaluftee. But the claim was void; the valley still belonged to the Indians.

John Walker had also ridden with Rutherford. His son Felix, a student and friend of Dr. Dobson, lawfully received in 1795 a sizable land grant to the valley. Young Walker was more than willing to let settlers attempt development of this wild area. Two North Carolina families decided to try. John Jacob Mingus and Ralph Hughes took their wives and children and journeyed into the “Lufty” regions of the Smokies. They cleared small homesteads by the river; they were all alone.

In 1803, Abraham Enloe and his family moved up from South Carolina and joined the growing families of Mingus and Hughes. Enloe chose land directly across the river from John Mingus, and by 1820 Abraham’s daughter Polly had married John, junior. “Dr. John,” as the younger Mingus was respectfully called in his later years, learned much about medicine from the scattered Cherokees remaining in the area.

Other families, Carolinian and Georgian and Virginian alike, arrived and stayed. Collins, Bradley, Beck, Conner, Floyd, Sherrill: these and others settled beside the river itself, and their children moved along the creeks and branches. Fresh lands were cleared, new homes built; the Oconaluftee was being transformed. And further to the southwest, Forney Creek was being claimed by Crisps and Monteiths, Coles and Welches; Deep Creek had already been[Pg 50] colonized by Abraham Wiggins and his descendants.

The Tennessee side of the Smokies, furrowed by its own series of rivers and creeks, awaited settlement. By 1800 a few Virginians and Carolinians were drifting into the four-year-old state of Tennessee, willing to settle.

The first family of Gatlinburg was probably a mother and her seven children. This widow, Martha Huskey Ogle, brought five sons and two daughters from Edgefield, South Carolina. Richard Reagan, a Scotch-Irishman from Virginia, and his family joined the Ogles and began to clear land. His son, Daniel Wesley Reagan, born in 1802, was the first child of the settlement and later became a leading citizen of the community. The elder Reagan was fatally injured when a heavy wind blew the limb from a tree on him, reminding the little community once more of the precarious nature of survival in this free, stern country.

Maples, Clabos, and Trenthams followed the Ogles and the Reagans into the Gatlinburg area. Nearby Big Greenbrier Cove became known as “the Whaley Settlement.” Some settlers traveled directly across the crest of the Smokies, via Indian and Newfound Gaps, but these old Cherokee trails and cattle paths were rough and overgrown. Horses could barely make it through, and most possessions had to be carried on stout human shoulders. Besides the usual pots, tools, guns, and seeds were the Bibles and treasured manmade mementos.

Many settlers, having been soldiers of the Revolution, had received 20-hectare (50-acre) land grants for a mere 75 cents. They pushed along the West Prong of the Little Pigeon River, past Gatlinburg, up among the steep slopes of the Bull Head, the Chimney Tops, the Sugarland Mountain. This narrow Sugarlands valley, strewn with water-smoothed boulders and homestead-sized plateaus of level land, attracted dozens of families. But this rocky country forced the settlers to clear their fields twice, first of the forest and then of the stones.

Edouard E. Exline

Uncle George Lamon sits next to one of his honey bee boxes at his home in Gumstand, near Gatlinburg.

The work of clearing demanded strong muscles, long hours, and sturdy spirits. It meant denting the hard armor of the forest and literally fighting for a tiny patch of cropland. Men axed the huge trees with stroke after grinding stroke, then either wrenched the stumps from the earth with teams of oxen or[Pg 51] burned them when they had dried. Some trees were so immense that all a man could do was “girdle” them, which meant deep-cutting a fatal circle into the bark to arrest the flow of sap. Such “deadenings” might stand for years with crops planted on the “new ground,” before the trees were finally cut and often burned. Logs and stumps from the virgin forest often smouldered for days or weeks.

The soil itself was rich and loamy with the topsoil of centuries. Land that had produced great forests could also nourish fine crops. During the first year of settlement, all able-bodied members of the family helped cultivate the new ground. Such land demanded particular attention. Using a single-pointed “Bull tongue” plow to bite deep into the earth and a sharp iron “coulter” to cut tough roots left under the massive stumps, a succession of plows, horses, and workers prepared and turned the newly cleared field. The first man “laid off” the rows into evenly spaced lengths, the second plowed an adjacent furrow, and the wife or children dropped in the seed. A third plow covered this planted row by furrowing along its side. A short while later, the same workers would “bust middles” by plowing three extra furrows into the ground between the seeded rows. This loosened the soil and destroyed any remaining roots.

While fields throughout the Smokies were yielding to the plow, even more isolated coves and creeks were being penetrated and settled. Gunters, Webbs, McGahas, and Suttons found their way into Big Creek. And in 1818, John Oliver walked into a secluded Tennessee cove, spent the night in an Indian hut, and then became familiar with one of the most beautiful and productive spots in all the Great Smokies. This broad, well-watered basin of fertile land was named after the wife of an old Cherokee chief; it was called Kate’s Cove, later Cades Cove.

John Oliver settled in that cove. Three years later—two years after the decisive 1819 treaty with the Cherokees—William Tipton settled there legally, bought up most of the land, and parceled it out to paying newcomers. David Foute came and established an iron forge in 1827. By mixing iron ore with limestone and charcoal, this “bloomery forge” produced chunks of iron called “blooms.” The forge, similar to many which sprang up throughout Appalachia, was indeed an asset, but its low-grade[Pg 52] ore and the cost of charcoal forced it to close only 20 years later.

Russell Gregory built a homestead high in the cove and ranged cattle on a nearby grassy bald. These mysterious open meadows scattered throughout the Smokies were of unknown origin. Had Indians kept them cleared in years gone by? Had some unexplained natural circumstance created them? Pioneers and later experts alike remained baffled and attracted by the lush grass which, growing among forest-covered crags and pinnacles, provided excellent forage for livestock. The present-day Parson’s and Gregory Balds were named for enterprising farmers who made early use of this phenomenon. Peter Cable, a friend of William Tipton, joined the valley settlement in Cades Cove. Cable’s son-in-law, Dan Lawson, expanded Cable’s holdings into a narrow mountain-to-mountain empire.

Cades Cove, with its vast farmland, soon rivaled Oconaluftee and Cataloochee. The lower end of the cove sometimes became swampy, but this pasture was reclaimed by a series of dikes and log booms. To escape an 1825 epidemic of typhoid in the Tennessee lowlands, Robert Shields and his family moved up into the hill-guarded cove. Two of his sons married John Oliver’s daughters and remained in Cades Cove. A community had been formed.

But the life in these small communities was not easy. Each family farmed for a living; each family homestead provided for its own needs and such luxuries as it could create. Isolation from outside markets made cash crops, and hence cash itself, relatively insignificant. The settlers of the Great Smokies depended upon themselves. They built their own cabins and corncribs, their own meat- and apple- and spring-houses. They cultivated a garden whose corn, potatoes, and other vegetables would last the family through the winter. They set about insuring a continuous supply of pork and fruit and grains, wool and sometimes cotton, and all the other commodities necessary to keep a family alive.

[Pg 53]

Edouard E. Exline

Most families had several scaffolds in their yards on which they dried fruits, beans, corn, and even duck and chicken feathers for stuffing pillows.

Charles S. Grossman

Near most houses was a smokehouse in which meat was cured and often stored for later use.

Charles S. Grossman

Fruits and other goods were stored in barns or sheds, often located over cool springs.

[Pg 54]

Edouard E. Exline

Food also was stored in pie safes. The pierced tin panels allow air into the cabinet but prevent flies from getting at the food.

Living off the land required both labor and ingenuity. These early settlers did not mind fishing and hunting for food throughout the spring, summer, and early fall, but there were also the demands of farming and livestock raising. They carved out of wood such essentials as ox yokes and wheat cradles,[Pg 55] spinning wheels and looms. Men patiently rebuilt and repaired anything from a broken harness to a sagging “shake” roof made of hand-riven shingles. Children picked quantities of wild berries and bushels of beans in sun-hot fields and gathered eggs from hidden hen nests in barn lofts and under bushes. They found firewood for the family, carried water from the spring, bundled fodder from cane and corn, and stacked hay for the cattle, horses, mules, and oxen.

Aiden Stevens

In the days before refrigerators, many methods and kinds of containers were used in preserving and storing foods. Corn meal, dried beans and other vegetables, and sulphured fruits were kept in bins made from hollow black gum logs.

Women made sure that the food supply stretched to last through the winter. They helped salt and cure pork from the hogs that their husbands slaughtered. They employed a variety of methods to preserve vital fruits and vegetables. Apples, as well as beans, were carefully dried in the hot summer or autumn sun; water, added months later, would restore a tangy flavor. Some foods were pickled in brine or vinegar.

Women also used sulphur as a preservative, especially with apples. Called simply “fruit” by the early settlers, apples such as the favorite Limbertwigs and Milams gave both variety and nutrition to the pioneer diet. A woman might peel and slice as much as two dishpans of “fruit” into a huge barrel. She would then lay a pan of sulphur on top of the apples and light the contents. By covering the barrel with a clean cloth, she could regulate the right amount of fumes held inside. The quickly sulfurated apples remained white all winter and were considered a delicacy by every mountain family.

Food, clothing, shelter, and incessant labor: these essentials formed only the foundation of a life. Intangible forces hovered at the edges and demanded fulfillment. As hardy and practical as the physical existence of the pioneers had to be, there was another dimension to life. The pioneers were human beings. Often isolated, sometimes lonely, they yearned for the comforts of myth and superstition and religion—and the roads that led in and out. The Cherokees in their time had created such comforts; they had woven their myths and had laced the Smokies with a network of trails. Now it was the white man’s turn.

The early settlers of the Great Smoky Mountains were not content to remain only in their hidden hollows and on their tiny homesteads. Challenging[Pg 56] the mountain ranges and the rough terrain, they constructed roads. In the mid-1830s, a project was undertaken to lay out a road across the crest of the Smokies and connect North Carolina’s Little Tennessee valley with potential markets in Knoxville, Tennessee. Although the North Carolina section was never completed, an old roadbed from Cades Cove to Spence Field is still in existence. When Julius Gregg established a licensed distillery in Cades Cove and processed brandy from apples and corn, farmers built a road from the cove down Tabcat Creek to the vast farmlands along the Little Tennessee River.

By far the most ambitious road project was the Oconaluftee Turnpike. In 1832, the North Carolina legislature chartered the Oconaluftee Turnpike Company. Abraham Enloe, Samuel Sherrill, John Beck, John Carroll, and Samuel Gibson were commissioners for the road and were authorized to sell stock and collect tolls. The road itself was to run from Oconaluftee all the way to the top of the Smokies at Indian Gap.

Work on the road progressed slowly. Bluffs and cliffs had to be avoided; such detours lengthened the turnpike considerably. Sometimes the rock was difficult to remove. Crude blasting—complete with hand-hammered holes, gunpowder inside hollow reeds, and fuses of straw or leaves—constituted one quick and sure, but more expensive, method. Occasionally, the men burned logs around the rock, then quickly showered it with creek water. When the rock split from the sudden change in temperature, it could then be quarried and graded out. Throughout the 1830s, residents of Oconaluftee and nearby valleys toiled and sweated to lay down this single roadbed.

This desire and effort to conquer the wilderness also prompted the establishment of churches and, to a lesser extent, schools. In the Tennessee Sugarlands, services were held under the trees until a small building was constructed at the beginning of the 19th century. The valley built a larger five-cornered Baptist church in 1816. Prospering Cades Cove established a Methodist church in 1830; its preacher rode the Little River circuit. Five years later, the church had 40 members.

Over on the Oconaluftee, Ralph Hughes had donated land and Dr. John Mingus had built a log schoolhouse. Monthly prayer meetings were held[Pg 57] there until the Lufty Baptist Church was officially organized in 1836. Its 21 charter members included most of the turnpike commissioners plus the large Mingus family. Five years later, the members built a log church at Smokemont on land donated by John Beck.

Nothing fostered these settlers’ early gropings toward community more than stories. Legends and tall tales, begun in family conversations and embellished by neighborly rumor, forged a bond, a unity of interest, a common history, in each valley and on each meandering branch. For example, in one western North Carolina tradition that would thrive well into the 20th century, Abraham Enloe was cited as the real father of Abraham Lincoln. Nancy Hanks, it was asserted, had worked for a time in the Enloe household and had become pregnant. Exiled to Kentucky, she married Thomas Lincoln but gave birth to Abraham’s child.

Stories mingled with superstition. The Cherokees dropped seven grains into every corn hill and never thinned their crop. Many early settlers of the Smokies believed that if corn came up missing in spots, some of the family would die within a year. Just as the Cherokees forbade counting green melons or stepping across the vines because “it would make the vines wither,” the Smokies settlers looked upon certain events as bad omens. A few days before Richard Reagan’s skull was fractured, a bird flew on the porch where he sat and came to rest on his head. Reagan himself saw it as a “death sign.”

Superstition, combined with Indian tradition, led to a strangely exact form of medicine. One recipe for general aches and pains consisted of star root, sourwood, rosemary, sawdust, anvil dust, water, and vinegar. A bad memory required a properly “sticky” tea made of cocklebur and jimsonweed.

A chief medicinal herb was an unusual wild plant known as ginseng. Called “sang” in mountain vernacular, its value lay in the manlike shape of its dual-pronged roots. Oriental cultures treasured ginseng, especially the older and larger roots. Reputed to cure anything from a cough to a boil to an internal disorder, it was also considered an aphrodisiac and a source of rare, mystical properties. But scientific research has never yielded any hard evidence of its medicinal worth.

[Pg 58]

Alan Rinehart

Aunt Sophie Campbell made clay pipes at her place on Crockett Mountain and sold them to her neighbors and to other folks in the Gatlinburg area.

Settlers used ginseng sparingly, for it brought a high price when sold to herb-dealers for shipment to China. The main problem lay in locating the five-leaved plants, which grew in the most secluded, damp coves of the Smokies. Sometimes several members of a family would wait until summer or early fall, then go out on extended “sanging” expeditions.

The search was not easy. During some seasons, the plant might not appear at all. When it did, its leaves yellowed and its berries reddened for only a few days. But when a healthy “sang” plant was finally found, and its long root carefully cleaned and dried, it could yield great financial reward. Although the 5-year-old white root was more common, a red-rooted plant needed a full decade to mature and was therefore especially prized. Greed often led to wanton destruction of the beds, with no seed-plants for future harvests. Ginseng was almost impossible to cultivate.

Ginseng-hunting became a dangerous business. Although Daniel Boone dug it and traded in it, later gatherers were sometimes killed over it. One large Philadelphia dealer who came into Cataloochee in the mid-1800s was murdered and robbed. Anyone trying to grow it, even if he were successful, found that he would have to guard the plants like water in a desert. Indeed, the rare, graceful ginseng became a symbol for many in the mountains of all that was unique, so readily destroyed, and eventually irreplaceable.

As much as the pioneers drew on Indian experience, they also depended on their own resourcefulness. One skill which the early settlers brought with them into the Smoky Mountains involved a power unknown to the Cherokees. This was the power of the rifle: both its manufacture and the knowledge of what the rifle could do.

The backwoods rifle was a product of the early American frontier. Formally known as the “Pennsylvania-Kentucky” rifle, this long-barreled innovation became a standby throughout the Appalachians. To assure precise workmanship, it was made out of the softest iron available. The inside of the barrel, or the bore, was painstakingly “rifled” with spiralling grooves. This gradual twist made the bullet fly harder and aim straighter toward its target. The butt of the weapon was crescent-shaped to keep the gun from[Pg 59] slipping. All shiny or highly visible metal was blackened, and sometimes a frontiersman would rub his gun barrel with a dulling stain or crushed leaf.

But the trademark of the “long rifle” was just that: its length. Weighing over 2.5 kilograms (5.5 pounds) and measuring more than 1.2 meters (4 feet), the barrel of the backwoods rifle could be unbalancing. Yet this drawback seemed minor compared to the superior accuracy of the new gun. The heavy barrel could take a much heavier powder charge than the lighter barrels, and this in turn could, as an expert noted, “drive the bullet faster, lower the trajectory, make the ball strike harder, and cause it to flatten out more on impact. It does not cause inaccurate flight....”

National Park Service

A young Smokies lad stands proudly with his long rifle and powder horn before heading off to the woods on a hunting excursion.

The Pennsylvania-Kentucky rifle became defender, gatherer of food, companion for thousands of husbands and fathers. Cradled on a rack of whittled wooden pegs or a buck’s antlers, the “rifle-gun” hung over the door or along the wall or above the “fire-board,” as the mantel was called, within easy and ready reach. It was the recognized symbol of the fact that each man’s cabin was his castle.

Equipped with a weapon such as this, pioneer Americans pushed back the frontier. The fastnesses of the Great Smoky Mountains gradually submitted to the probing and settling of the white man. The fertile valleys were settled, the hidden coves were conquered. The Oconaluftee Turnpike to the top of the Smokies was completed in 1839. And in that fateful year, disaster was stalking a people who had known the high mountains but who had not known of the ways of making a rifle.

[Pg 60]

National Park Service

Of all the special tasks in the Great Smoky Mountains, rifle making was perhaps the most intricate and the most intriguing. From the forging of the barrel to the filing of the double trigger and the carving of the stock, the construction of the “long rifle” proved to be a process both painstaking and exciting. After the barrel was shaped on the anvil, its bore was cleaned to a glass-like finish by inserting and turning an iron rod with steel cutters. When the rod could cut no more, the shavings from the bore were removed. The rifling of the barrel, or cutting the necessary twists into the bore, required a 3-meters-long (10-foot) assembly, complete with barrel, cutting rod, and rifling guide. The 1.5-meter (5-foot) wooden guide, whose parallel twists had been carefully cut into it with a knife, could be turned by a man pushing it through the spiral-edged hole of a stationary “head block.” The resulting force and spin drove the cutting rod and its tiny saw into the barrel, guiding its movement as it “rifled” the gun.

[Pg 61]

Most of the rifles in the Smokies had an average spin or twist of about one turn in 122 centimeters (48 inches), the ordinary original length of the barrel. A later step—“dressing out” the barrel with a greased hickory stick and a finishing saw—usually took a day and a half to be done right. Likewise, the making of a maple or walnut rifle stock, or the forging of the bullet mold, led gunsmiths to adopt the long view of time and the passing of days in the Great Smoky Mountains. Two such gunsmiths were Matt Ownby and Wiley Gibson. Ownby (far left) fits a barrel to an unfinished stock as the process of rifle making nears its end. Gibson (below), the last of four generations of famous Smoky Mountain gunsmiths, works at his forge in Sevier County, Tennessee. Over the years Gibson lived in several places in Sevier County, and in each one he set up a gun shop. As he tested one of his finished products (left), Gibson commented: “I can knock a squirrel pine blank out of a tree at 60 yards.”

[Pg 62]

Walini was among the Cherokees living on the Qualla Reservation in North Carolina when James Mooney visited in 1888.

Smithsonian Institution

[Pg 63]

The Cherokees who remained in the East endured many changes in the early 1800s.

As their Nation dwindled in size to cover only portions of Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, and Tennessee, the influence of growing white settlements began to encroach on the old ways, the accepted beliefs. Settlers intermarried with Indians. Aspects of the Nation’s civilization gradually grew to resemble that of the surrounding states.

The Cherokees diversified and improved their agricultural economy. They came to rely more heavily on livestock. Herds of sheep, goats, and hogs, as well as cattle, grazed throughout the Nation. Along with crops of aromatic tobacco, and such staples as squash, potatoes, beans, and the ever-present corn, the Cherokees were cultivating cotton, grains, indigo, and other trade items. Boats carried tons of export to New Orleans and other river cities. Home industry, such as spinning and weaving, multiplied; local merchants thrived.

Church missions and their attendant schools were established. As early as 1801, members of the Society of United Brethren set up a station of missionaries at a north Georgia site called Spring Place. And within five years, the Rev. Gideon Blackburn from East Tennessee persuaded his Presbyterians to subsidize two schools.

In 1817, perhaps the most famous of all the Cherokee missions was opened on Chickamauga Creek at Brainerd, just across the Tennessee line from Georgia. Founded by Cyrus Kingsbury and a combined Congregational-Presbyterian board, Brainerd Mission educated many Cherokee leaders, including Elias Boudinot and John Ridge. Samuel Austin Worcester, a prominent Congregational minister from New England, taught at Brainerd from 1825 until 1834. He became a great friend of the Cherokees and was referred to as “The Messenger.”

In 1821, a single individual gave to his Nation an educational innovation as significant and far-reaching as the influx of schools. A Cherokee named Sequoyah, known among whites as George Gist, had long been interested in the “talking leaves” of the white man. After years of thought, study, and hard work, he devised an 86-character Cherokee alphabet. Born about 1760 near old Fort Loudoun, Tennessee, Sequoyah had neither attended school nor learned[Pg 64] English. By 1818, he had moved to Willstown in what is now eastern Alabama and had grown interested in the white man’s ability to write. He determined that he would give his own people the same advantage.